Dear Editor.

Evidence supports that almost 60% of COVID-19 survivors will experience post-COVID symptoms during the first months after infection.1 These symptoms lead to a decrease in health-related quality of life and function.2 One full-text3 and three letters to the editor4, 5, 6 published in Journal of Infection have evaluated the presence of functional limitations as post-COVID sequalae in individuals who had survived to COVID-19. Most of studies investigating post-COVID functional limitations are cross-sectional since they assessed related-disability just at one follow-up period. Understanding the longitudinal evolution of post-COVID functional limitations might have implications for optimizing patient care and public health outcomes. We present here two approaches for potentially analyzing the longitudinal recovery curves of post-COVID functional limitations in a sample of previously hospitalized COVID-19 survivors: (1) mosaic plots of the prevalence of functional limitations during the first year after hospitalization; and, (2) a bar plot of the evolution of functional limitations, fitted with an exponential decay model to help in its longitudinal interpretation.

The LONG-COVID-EXP-CM is a multicenter cohort study including individuals with a diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 (ICD-10 code) by RT-PCR technique and radiological findings hospitalized during the first wave of the pandemic (from March 10 to May 31, 2020) in five urban hospitals of Madrid (Spain). From all patients hospitalized during the first wave, a sample of 400 individuals from each hospital was randomly selected. The Ethics Committees of all hospitals approved the study (HCSC20/495E, HSO25112020, HUFA 20/126, HUIL/092–20, HUF/EC1517). Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Patients were scheduled for a telephone interview conducted by trained healthcare professionals at two follow-up periods with a 5-month period in between to evaluate the functional status of the patient. Participants were asked for self-perceived limitations in occupational, leisure/social activities, instrumental, and basic daily living activities as we previously described the relevance of specifically asking for different activities.5 They were asked for determining their functional status at the moment of the interview (post-COVID) in comparison with their previous status before hospitalization. Clinical features (i.e., age, gender, height, weight, medical comorbidities) and hospitalization data (e.g., COVID-19 symptoms at hospital admission, days at the hospital, and intensive care unit admission) were collected from hospital medical records.

Mosaic plots were created with Python's library statsmodels 0.11.1 while Matplotlib 3.3.4 was used for the bar plots. The exponential curves were fitted to the data according to the formula , where represents the modeled prevalence of the functional limitation (occupational, leisure/social activities, instrumental, and basic) at a time (in months), and and are the parameters of the model.

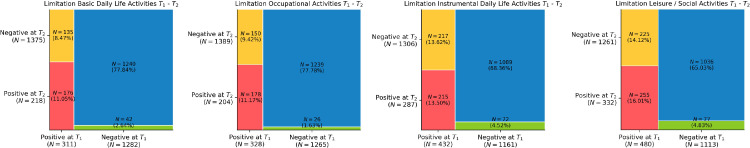

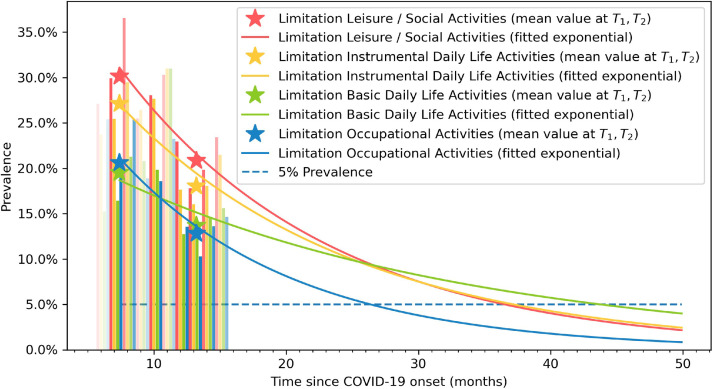

From 2000 patients randomly selected and invited to participate, a total of 1593 (80.9%) completed both assessments. Patients were assessed at T1 (mean: 8.4, range 6–10) and T2 (mean: 13.2, range 11–15) months after hospital discharge. Between 20 and 30% of participants reported limitations during at least one daily living activity. Fig. 1 shows mosaic plots of self-perceived limitations in occupational, leisure/social activities, instrumental, and basic daily living activities comparing T1 to T2. Looking at Fig. 1, self-perceived limitations in daily living activities decreased during the following year after the infection (occupational activities from 20.9% at T1 to 12.8% at T2; leisure/social activities from 30.1% at T1 to 20.8% at T2; instrumental activities from 27.1% at T1 to 18.1% at T2; and basic activities from 19.9% at T1 to 13.7% at T2). In Fig. 2 , vertical bars represent the percentage of patients reporting limitations at daily living activities at any time (opacity approximately indicates the sample size at a particular time). The mean values used for the development of the mosaic plots have been marked with asterisks in the graphs. Finally, fitted exponential curves were added to visualize the prevalence trend.

Fig. 1.

Mosaic plots of self-reported limitations with daily living activities at T1 (8.4 months after hospital discharge) vs T2 (13.2 months after hospital discharge).

Fig. 2.

Recovery curve of self-reported post-COVID limitations with leisure/social (in red), instrumental (in yellow), basic (in green) and occupational (in blue) daily living activities. Opacity indicates the sample size at that follow-up time. Asterisks represent the mean values taken at T1 and T2 follow-up periods.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first analysis showing the recovery curves of post-COVID functional limitations in previously hospitalized COVID-19 survivors. The mosaic plots showed that a large number of patients developed “de novo” functional limitations after the infection. Despite this, more individuals recovered their functional status during daily living activities than those developing functional limitation, explaining the decrease prevalence trend observed. This decrease was, however, not as pronounced as expected suggesting that functional limitations during daily living activities will be long-lasting post-COVID sequelae. Although previous studies have investigated health-related quality of life in COVID-19 survivors, we differentiated the type of daily living activity perceived as limited, a distinction that is not commonly conducted in former post-COVID literature. The exponential recovery curves identified suggest that limitations during basic daily living activities showed the less pronounced decrease tendency and could be present up to five years after infection. Identification of risk factors associated to these functional limitations would help for early identification and monitorization of patients at a high risk of developing functional limitations as post-COVID sequelae. In fact, the number of COVID-19 associated onset symptoms at hospital admission (high symptom load), intensive care unit admission and female sex have been identified as risk factors associated with functional limitations.5

Although this is the first-time using mosaic plots and tendency analysis for analysis the recovery curves of post-COVID functional status with a large and multicenter design, potential weaknesses should be also admitted. First, only hospitalized individuals aged 60-years old were included. Second, we collected self-reported functional limitations on daily living activities. The use of validated questionnaires, e.g., EuroQol-5D, assessing health-related quality of life could help to characterizing functional status of COVID-19 survivors. Finally, we did not collect objective data of COVID-19 severity and measures of lung damage, although current literature suggests that these factors are not related to post-COVID sequelae.

In conclusion, our tendency analysis revealed that post-COVID functional limitations during daily living activities tend to slowly recover during the following five years after SARS-CoV-2 infection in previously hospitalized COVID-19 survivors.

Consent to participate

Participants provided informed consent before collecting data.

Consent for publication

No personal info of any patient is provided in the text.

Role of the funding source

The LONG-COVID-EXP-CM is supported by a grant of Comunidad de Madrid y la Unión Europea, a través del Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER), Recursos REACT-UE del Programa Operativo de Madrid 2014-2020, financiado como parte de la respuesta de la Unión a la pandemia de COVID-19. The sponsor had no role in the design, collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data, draft, review, or approval of the manuscript or its content. The authors were responsible for the decision to submit the manuscript for publication, and the sponsor did not participate in this decision.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study concept and design. CFdlP, JMG and OPV conducted literature review and did the statistical analysis. All authors recruited participants and collected data. OPV supervised the study. All authors contributed to interpretation of data. All authors contributed to drafting the paper. All authors revised the text for intellectual content and have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Declaration of Competing Interest

No conflict of interest is declared by any of the authors

References

- 1.Fernández-de-las-Peñas C., Palacios-Ceña D., Gómez-Mayordomo V., Florencio L.L., Cuadrado M.L., Plaza-Manzano G., et al. Prevalence of post-COVID-19 symptoms in hospitalized and non-hospitalized COVID-19 survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Int Med. 2021;92(2021):55–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2021.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Malik P., Patel K., Pinto C., Jaiswal R., Tirupathi R., Pillai S., et al. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome (PCS) and health-related quality of life (HRQoL): a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Virol. 2022;94:253–262. doi: 10.1002/jmv.27309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taboada M., Cariñena A., Moreno E., et al. Post-COVID-19 functional status six-months after hospitalization. J Infect. 2021;82:e31–e33. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garratt A.M., Ghanima W., Einvik G., Stavem K. Quality of life after COVID-19 without hospitalisation: good overall, but reduced in some dimensions. J Infect. 2021;82:186–230. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2021.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fernández-de-las-Peñas C., Martín-Guerrero J.D., Navarro-Pardo E., Rodríguez-Jiménez J., Pellicer-Valero O.J. Post-COVID functional limitations on daily living activities are associated with symptoms experienced at the acute phase of SARS-CoV-2 infection and internal care unit admission: a multicenter study. J Infect. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2021.08.009. Aug 8S0163-4453(21)00391-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rubeshkumar P., John A., Narnaware M., Jagadeesan M., Vidya F., Gurunathan R., et al. Persistent post COVID-19 symptoms and functional status after 12-14 weeks of recovery, Tamil Nadu, India, 2021. J Infect. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2021.12.019. Dec 22S0163-4453(21)00632-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]