Abstract

To address the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic caused by infection with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), a recombinant subunit vaccine, AKS-452, is being developed comprising an Fc fusion protein of the SARS-CoV-2 viral spike protein receptor binding domain (SP/RBD) antigen and human IgG1 Fc emulsified in the water-in-oil adjuvant, Montanide™ ISA 720. A single-center, open-label, phase I dose-finding and safety study was conducted with 60 healthy adults (18–65 years) receiving one or two doses 28 days apart of 22.5 µg, 45 µg, or 90 µg of AKS-452 (i.e., six cohorts, N = 10 subjects per cohort). Primary endpoints were safety and reactogenicity and secondary endpoints were immunogenicity assessments. No AEs ≥ 3, no SAEs attributable to AKS-452, and no SARS-CoV-2 viral infections occurred during the study. Seroconversion rates of anti-SARS-CoV-2 SP/RBD IgG titers in the 22.5, 45, and 90 µg cohorts at day 28 were 70%, 90%, and 100%, respectively, which all increased to 100% at day 56 (except 89% for the single-dose 22.5 µg cohort). All IgG titers were Th1-isotype skewed and efficiently bound mutant SP/RBD from several SARS-CoV-2 variants with strong neutralization potencies of live virus infection of cells (including alpha and delta variants). The favorable safety and immunogenicity profiles of this phase I study (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT04681092) support phase II initiation of this room-temperature stable vaccine that can be rapidly and inexpensively manufactured to serve vaccination at a global scale without the need of a complex distribution or cold chain.

Keywords: Infectious disease, Coronavirus, Prophylaxis, Pandemic, COVID-19, Fc-fusion, SARS-CoV-2, AKS-452, Vaccine

Abbreviations: ACE2, angiotensin converting enzyme-2; AE, adverse event; ELISA, Enzyme Linked Immunosorbent Assay; HCS, human convalescent serum; SAE, serious adverse event; SP, Spike Protein; SP/RBD, spike protein receptor binding domain

1. Background

The global COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in millions of cases and deaths due to infection of the novel SARS-CoV-2 virus [1]. Indeed, a variety of vaccines are in development as a large-scale public health measure to control the pandemic [2], [3], in which some have demonstrated significant protective efficacy and acceptable safety profiles in relatively short Phase III studies [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11] which led to their Emergency Use Authorization [12]. Challenges of global distribution of and access to COVID-19 vaccines can be addressed with improved costs and speed of manufacturing, along with reasonable non-cold-chain vaccine storage [13], [14]. Such a high-expressing and stable recombinant subunit vaccine candidate, AKS-452, contains an Fc fusion protein antigen comprising the SARS-CoV-2 SP/RBD and the human IgG1 Fc region formulated in the water-in-oil adjuvant, Montanide™ ISA 720 [15]. The Fc moiety is designed to act as a mild adjuvant by inducing activation signals via Fcγ receptors expressed on antigen-presenting cells and to work in concert with a strong adjuvant to enhance the duration of antigen exposure to antigen-presenting cells and potentially direct antigen entry into lymph nodes locally and systemically where additional antigen-presenting cells reside. Indeed, the combination of Fc and adjuvant is expected to create a dramatic dose-sparing potential such that the risk of acute reactogenicity is reduced while immunogenicity is optimized, as demonstrated in animal studies [15]. Here, interim results are described for the phase I portion of a combined phase I/II safety and immunogenicity clinical trial (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT04681092) involving a single-center, University Medical Center Groningen (UMCG) in The Netherlands, in which COVID-19-naïve healthy adults between 18 and 65 years of age received one of three dose levels in one or two doses to evaluate the safety, reactogenicity, and immunogenicity of AKS-452.

2. Methods

2.1. Vaccine components

AKS-452 is a recombinant fusion protein comprising SP/RBD and an Fc fragment containing a portion of the hinge region, in which the full CH2 and CH3 domains of the human IgG1 Fc fragment are connected via a covalent peptide linker sequence, all encoded by a single nucleic acid molecule expressed in CHO-K1 cells as previously described [15] (#MDS0002, 586 µg/ml; Akston Biosciences, Beverly, MA; see PCT/US21/26577 for details). AKS-452 was expressed in a CHO-K1 cell line derivative (LakePharma, Belmont, CA), harvested via depth filtration (Pall Corporation, Port Washington, NY), purified via Protein-A affinity chromatography (MabSelect Sure, Cytiva Life Sciences, Marlborough, MA) followed by buffer exchange, further purified via anion exchange chromatography (Q-HP resin, Cytiva) with final buffer exchange, and concentrated via ultrafiltration-diafiltration (TengenX SIUS 30 kDa, Repligen, Waltham, MA) to 586 µg/mL confirmed by BCA method. Final drug substance was identified via a size exclusion chromatography method with UV–Visible detection (SEC/UV–Vis) which was consistent with that of the reference standard. The batch was > 98% pure with respect to molecular aggregates via SEC-HPLC and fragments via capillary electrophoresis-sodium dodecyl sulfate (CE-SDS) analysis (see Supplemental Methods and Table S1 for production and characterization details). The expression yield was 0.75 g/L for material used in this study and has since been optimized to approximately 3 g/L, compared to less than 0.1 g/L for non-Fc modified full-length SP produced in the same expression system. AKS-452 drug substance was manufactured into sterile AKS-452 drug product at PRA Health Sciences (Groningen, Netherlands) in vials containing 1 mL of AKS-452 at 583 µg/mL (#TGR20644/ AKS452/ 01Dec20). Drug product was stored at -80 °C and thawed immediately prior to final preparation. Data from stability studies currently in progress support storage at 2–8 °C and 25 °C for at least six months (see Tables S2 and S3). AKS-452 drug product was released for clinical use from PRA after passing pH, Osmolality, Appearance, Sterility, Endotoxin Content, Particulate Matter, Extractable Volume, Identity, Concentration, Potency, Aggregate Content, Isoelectric point, and Fragment content release criteria (see Supplemental Methods and Table S1 for production and characterization details). This sterile aqueous solution of AKS-452 was emulsified in the water-in-oil adjuvant, Montanide™ ISA 720 (#2587851 Seppic S.A., Paris, France; 30%/70% aqueous antigen/adjuvant emulsification) [16], [17] and administered to subjects within 24 h of preparation (see details of manufacturing, stability, and clinical formulations in Supplemental Methods).

2.2. Procedures

Upon enrollment, subjects were assigned in a non-randomized manner to one of the cohorts. The first 3 subjects of cohorts 1,3,5 were vaccinated in a consecutive order in which the first subject was observed 2 h post-vaccination before the second subject of the respective cohort received vaccination, and the third subject was treated in a similar fashion. After the third subject in a cohort had been vaccinated and observed for 2 h, the next 7 subjects of the respective cohort were vaccinated simultaneously and in a shorter period of time (Total N = 10). Subjects of cohorts 2, 4, and 6 received injections simultaneously (i.e., not in consecutive order) because dosages had been considered safe as a result of the respective single-dose cohort. Final safety review and immunogenicity assessments were performed at days 28 and 56 with follow-up assessments scheduled for 90 and 180 days after the first injection. An informed consent form was signed voluntarily before any study-related procedure was performed, indicating that the subject understood the purpose and procedures required for the study and was willing to participate.

2.3. Trial oversight

The trial was reviewed and approved by the Central Committee on Research involving Humans in The Hague, together with a marginal review by the competent authority (Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport (VWS)). Local feasibility was assessed and approved by the UMCG Institutional Review Board. For release of the trial at the clinical site, the UMCG was the regulatory sponsor, and the Contract Research Organization responsible for management of the entire clinical project was TRACER BV (The Netherlands). The trial was funded by Akston Biosciences Corp. (Beverly, MA), in which Akston, TRACER BV, PRA Health Sciences, and UMCG representatives designed and manufactured the vaccine candidate, designed the trial, developed the statistical analysis plan, and performed the analyses. The decision to submit the manuscript for publication was made by all authors who vouch for the accuracy and completeness of the reported data and for the fidelity of the trial to the protocol. No one who is not an author contributed to the preparation of the manuscript.

2.4. Primary and secondary end points

Primary endpoints were safety and reactogenicity of each dose schedule, and secondary endpoints were humoral immunogenicity that included anti-SP/RBD-specific IgG titers, inhibitory/neutralization potencies, IgG isotyping as a measure of Th1/Th2 response ratios, and binding titers to mutant SP/RBD of different SARS-CoV-2 variant strains (these immunogenicity assessments were made on days 0, 28, and 56). Subjects were instructed to note every change in health or wellbeing after vaccination. At all follow-up appointments throughout the trial, adverse events (AEs) and serious adverse events (SAEs) were discussed via an open discussion followed by a symptom questionnaire. Participants could also contact clinical trial researchers (via contact information on the emergency card) to report symptoms at any moment between follow-up appointments. AEs were graded by a numerical score according to the defined NCI Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (NCI CTCAE) version number V4.03. Safety data are included up to the day 56 interim cutoff date of June 22, 2021 for all cohorts.

2.5. Laboratory analyses

Different types of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) were used to measure SARS-CoV-2 SP/RBD-specific binding IgG titers (see details in Supplemental Methods). A semi-quantitative screening ELISA (SARS-CoV-2 IgG, ARCHITECT I System, Abbott, Sligo, Ireland) was performed at the UMCG that detected anti-SARS-CoV-2 SP IgG titers in which validated negative or positive cutoff values were used as inclusion or exclusion enrollment criteria, respectively, during screening. A quantitative anti-SP/RBD IgG titer ELISA (AntiCoV-ID™ IgG ELISA, Akston Biosciences, Beverly, MA) was used to assess titers at baseline and on days 28 and 56 post-vaccination in which seropositivity was defined as a titer greater than 4.5 standard deviations above the value obtained using sera from 80 COVID-19-naïve subjects (i.e., 2.42 µg/mL, data not shown; this cutoff was confirmed via 36 serum samples from COVID-19 convalescent subjects, see HCS data in Fig. 2 A). Assessment of anti-SP/RBD titers to bind a series of SP/RBD mutant proteins from known SARS-CoV-2 variants and different IgG isotypes of anti-SP/RBD IgG titers were determined by ELISA. Serum IgG titer potency to inhibit binding of recombinant SP/RBD to recombinant angiotensin-converting enzyme II (ACE2) generating % inhibition values at 40x dilution and inhibitory dilution 50% (ID50) values were performed at Akston Biosciences (Beverly, MA) as previously described [15]. Scientists at Baylor College of Medicine and Texas Children’s Hospital (Houston, TX) using the SARS-CoV-2 viral strains: Washington (USA-WA1/2020; World Reference Center for Emerging Viruses and Arboviruses, University of Texas Medical Branch, TX, USA; GenBank accession no. MN985325.1), Alpha (NR-54011, Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Obtained Through BEI Resources, Manassas, VA, USA), and Delta (NR-55611, Source: St. Jude Children's Research Hospital, Obtained Through BEI Resources, Manassas, VA, USA), measured SARS-CoV-2 serum neutralizing titers via a Plaque Neutralization Test generating % inhibition values starting at 40x dilution with a two-fold dilution series. All assays were conducted in a blinded fashion and were performed as previously described [15], [18] or included in Supplementary Methods. HCS samples from subjects known to have acquired COVID-19 that recovered to an asymptomatic state for at least 14 days prior to serum collection were purchased or obtained from BioIVT (Westbury, NY), Invent Diagnostica (Hennigsdorf, Germany), and locally sourced donors under informed consent.

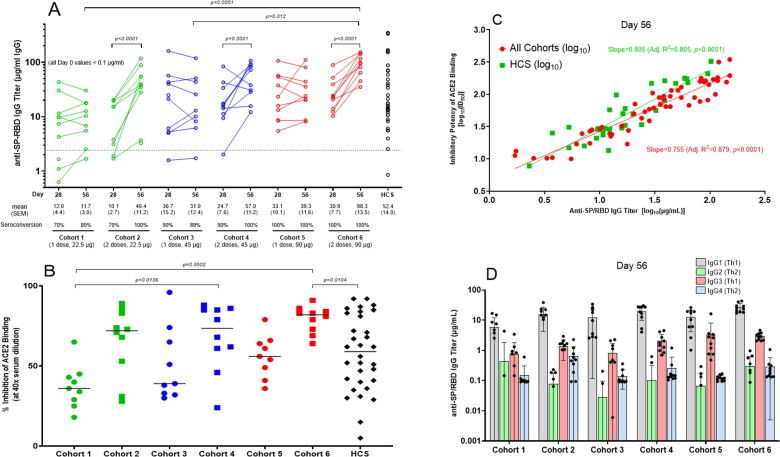

Fig. 2.

AKS-452 Phase 1 study immunogenicity. (A) Serum samples were obtained at Day 0, 28, and 56 of initial vaccine dose and assessed for anti-SP/RBD IgG binding titers via ELISA and presented per subject (all Day 0 samples were < lower limit of quantitation; not shown). Seroconversion was defined as > 2.42 µg/mL IgG (derived from validation studies with COVID-19 naïve subject samples; see Methods). Human Convalescent serum (HCS) was used as a comparator for samples from vaccinated subjects. Statistical comparisons between Day for each cohort and between cohorts were performed using a model with cohort and Day as fixed effects and a random subject effect. p-values were adjusted for multiplicity. (B) % Inhibition at a 1:40 dilution of sera of Day 56 serum samples were derived via a human ACE2 binding to SP/RBD ELISA. Statistical comparisons between cohorts were performed using a model with cohort as a fixed effect. p-values were adjusted for multiplicity. (C) Comparison of IgG titer vs. inhibitory potency (inhibitory dilution 50% in ACE2 binding assay, ID50) of Day 56 sera for vaccinated subjects and HCS. Linear regression was performed on log transformed data. The slope for HCS was found to be significantly higher (p < 0.0001). (D) Anti-SP/RBD IgG isotype titers were obtained via isotype-specific ELISAs (mean µg/mL ± SD).

2.6. Statistical analysis

A total of 60 participants was deemed sufficient to provide a descriptive safety and immunogenicity assessment. Patient demographic characteristics (such as age, sex, race, ethnicity, BMI, medical history, and morbidity) were displayed as (geometric) means with standard deviations, medians with range and frequencies. Continuous variables were tested for normal distribution and if non-normally distributed, data was transformed to obtain a normal distribution. Immunogenicity data were log-transformed (except for PRNT data) before performing 1-way or 2-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests, as appropriate, using SAS® for Windows™ Version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc.). Tukey adjustment for multiple comparisons was used or Dunnett adjustment when comparing with one control group. Specific statistical analyses and results are described in detail in each figure caption.

3. Results

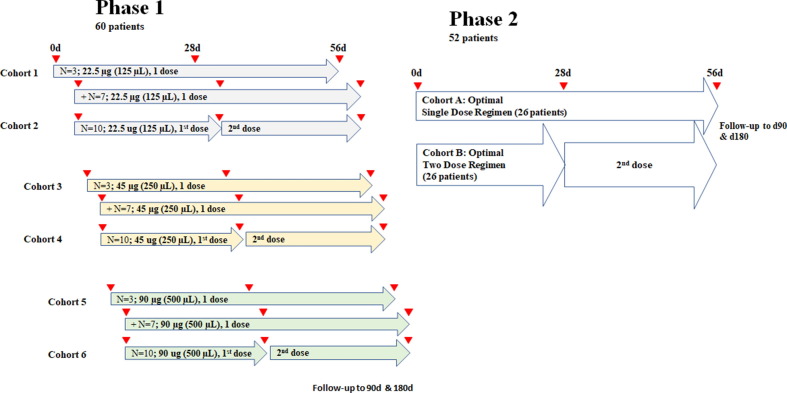

3.1. Trial design and participants

This phase I study was designed as part of a combined phase I/II study in which phase II will investigate safety and efficacy against COVID-19 (ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT04681092; see Clinical Protocol in Supplementary Materials; Fig. 1). This was an open-label, dose-finding, and safety phase I study initiated on April 6, 2021 at a single center (UMCG) to evaluate safety and immunogenicity parameters of AKS-452 emulsified in Montanide™ ISA 720. Trial participants included healthy adults between the ages 18 and 65 years of age that were COVID-19 seronegative (SARS-CoV-2 IgG, ARCHITECT I System, Abbott, Sligo, Ireland) and confirmed never to have contracted COVID-19 via questionnaire. This study population was a representation of the general population in terms of sex, ethnic background, and COVID-19 status. A total of 60 subjects participated in the trial, 32 men (46.7%) and 28 women (53.3%) with a mean age of 43.5 years (range 18–61 years; see Table 1 for demographics). Each were assigned to one of six cohorts (i.e., 10 subjects per cohort) to receive either one dose of 22.5 µg in 125 µL (cohort 1), 45 µg in 250 µL (cohort 3), or 90 µg in 500 µL (cohort 5), or two doses 28 days apart of 22.5 µg in 125 µL (cohort 2), 45 µg in 250 µL (cohort 4), or 90 µg in 500 µL (cohort 6) of AKS-452 emulsified in Montanide™ ISA 720 administered via subcutaneous route in the upper arm. The total study duration is 6 months which is currently in progress and results up to Day 56 are presented here. All enrolled subjects showed negative results in the anti-SP IgG screening ELISA. Note that 3 subjects, one from each of the single-dose cohorts 1, 3, and 5, opted to receive an emergency authorized vaccine between their Day 28 and Day 56 visits. Therefore, their data were excluded from the Day 56 immunogenicity and neutralization analyses.

Fig. 1.

AKS-452 pH 1/2 clinical study design. Phase 1 was a 6 × 3 (Sentinel) + 6 × 7 (Expansion) design. The first 3 (sentinel) subjects of cohorts 1, 3 and 5 were vaccinated in a consecutive order, in which the first subject was observed 2 h post-vaccination before the second subject of the respective cohort received vaccination, and the third subject was treated in a similar fashion. After the third subject in a cohort had been vaccinated and observed for 2 h, the next 7 subjects of the respective cohort were vaccinated simultaneously and in a shorter period (total n = 10). Subjects of cohorts 2, 4 and 6 received injections simultaneously with the expansion group of the respective single-dose cohort, because dosages had been considered safe. Based on safety and immunogenicity (seroconversion/titers) of Phase 1 cohorts, optimal dose levels for one-dose and two-dose strategy will be selected for Phase 2 cohorts.

Table 1.

AKS-452 Phase 1 Characteristics of Subjects at Baseline.

| Characteristic |

Cohort 1 (1 × 22.5 µg) |

Cohort 2 (2 × 22.5 µg) |

Cohort 3 (1 × 45 µg) |

Cohort 4 (2 × 45 µg) |

Cohort 5 (1 × 90 µg) |

Cohort 6 (2 × 90 µg) |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Subjects | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 60 |

| Sex (N) | |||||||

| Male | 6 | 5 | 4 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 32 (53.3%) |

| Female | 4 | 5 | 6 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 28 (46.7%) |

| Age (years) | |||||||

| Mean | 48 | 46.9 | 36.7 | 44.2 | 41.9 | 43.3 | 43.5 |

| Range | 19–58 | 28–60 | 23–58 | 18–61 | 20–58 | 21–58 | 18–61 |

| Race/Ethnicity (N) | |||||||

| Caucasian | 10 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 59 (98.3%) |

| other | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.7%) |

| Body Mass Index [Median (range)] | 25.27 (21.67–27.78) | 26.22 (21.38–30.06) | 23.99 (20.30–28.27) | 24.19 (21.10–29.97) | 23.64 (19.75–28.66) | 22.91 (20.17–28.98) | 24.03 (19.75–30.06) |

| SARS-Cov-2 seronegative (N) | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 60 |

| Allergies - N | |||||||

| Food allergy | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 (3.3%) |

| medication allergy | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 (3.3%) |

| Pollen allergy/hay fever | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 13 (21.7%) |

| Insect venom allergy | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 (3.3%) |

| Contact allergy | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 (3.3%) |

| Other allergy | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 (5.0%) |

| No allergy | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 6 | 39 (65.0%) |

| Congenital abnormalities (N) | |||||||

| Non-cardiac abnormalities | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 (5.0%) |

| No abnormalities | 9 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 57 (95.0%) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index (N) | |||||||

| “0” score | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 60 (100%) |

| Medication use during month prior to screening (N) | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 19 (31.7%) |

| Stomach protection | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 3 (5.0%) |

| Hormone treatment | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 (3.3%) |

| Antihypertensive drugs | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.7%) |

| Other | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 16 (30.0%) |

3.2. Safety assessment

None of the sentinel subjects (n = 3) in any dosing cohort had an AE ≥ grade 3 or SAE attributable to AKS-452 dosing, and therefore the remainder of each dosing cohort was expanded with an additional 7 patients, totaling 10 patients per cohort that received vaccine. Twenty-four systemic symptoms (grade 1) were reported by 19 subjects during the study. The majority of AEs were local symptoms that clustered to ‘injection site nodule’ and ‘injection site reaction’ for the first injection, which dramatically decreased in frequency after the second injection (Table 2 ). Furthermore, the majority of AEs occurred within 24 h of dosing which subsided within days to weeks after appearance with no residual complaints (Table 2). No SAE’s were reported during this study. No aberrations in laboratory values related to the vaccine were observed (see Table S4).

Table 2.

AKS-452 Phase 1 Overview of AEs per cohort.

| C1* | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 | C6 | Total AE's | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptoms | Number of Events | ||||||

| Systemic | AEs after FIRST dose < 24 h|>24 h | ||||||

| Chills | 1|0 | 1 | |||||

| General malaise | 0|1 | 1|0 | 0|1 | 3 | |||

| Headache | 1|0 | 2|0 | 1|0 | 1|0 | 1|1 | 7 | |

| Nausea | 1|0 | 1 | |||||

| Neck rigid | 1|0 | 1 | |||||

| Orthostatic collapse | 1|0 | 1 | |||||

| Tiredness | 1|0 | 1|0 | 2 | ||||

| Alopecia areata | 0|1 | 1 | |||||

| Calf pain | 0|1 | 1 | |||||

| Dizziness | 0|1 | 1 | |||||

| Fracture bone | 0|1 | 1 | |||||

| Taste metallic | 0|1 | 1 | |||||

| Tonsillitis | 0|1 | 1 | |||||

| Local | AEs after FIRST dose < 24 h|>24 h | ||||||

| Injection site hematoma | 1|0 | 0|1 | 2 | ||||

| Injection site nodule | 1|1 | 1|0 | 0|2 | 1|0 | 6 | ||

| Injection site reaction | 2|2 | 0|1 | 5|4 | 1|2 | 0|2 | 3|7 | 29 |

| Irritation skin | 1|0 | 1|0 | 2 | ||||

| Painful arm | 1|0 | 3|0 | 3|0 | 7 | |||

| Rash urticaria-like | 0|1 | 1 | |||||

| Systemic and Local | AEs after SECOND dose < 24 h|>24 h | ||||||

| General malaise | 1|0 | 1 | |||||

| Headache | 1|0 | 1 | |||||

| Injection site hematoma | 1|0 | 1 | |||||

| Injection site nodule | 0|2 | 1|0 | 4|1 | 8 | |||

| Injection site reaction | 4|0 | 5|0 | 4|0 | 13 | |||

| Injection site swelling | 1|0 | 1 | |||||

| Painful arm | 1|0 | 1 | |||||

| *Cohort 1 (1dose × 22.5 µg); Cohort 2 (2 doses × 22.5 µg); Cohort 3 | |||||||

| (1 dose × 45 µg); Cohort 4 (2 doses × 45 µg); Cohort 5 (1 dose × 90 µg); Cohort 6 (2 doses × 90 µg) | |||||||

3.3. IgG titers and seroconversion rates

Anti-SP/RBD IgG titers 28 days after a single administration of 22.5 µg (cohorts 1 and 2), 45 µg (cohorts 3 and 4), and 90 µg (cohorts 5 and 6) AKS-452 resulted in significantly higher titers induced by the 45 µg and 90 µg cohorts relative to the 22.5 µg cohorts (p = 0.0097, 22.5 vs. 45 µg; p = 0.0006, 22.5 vs. 90 µg), but no significant difference was observed between the 45 and 90 µg cohorts (p = 0.609; Fig. 2 A). However, administration of a second dose (i.e., Cohorts 2, 4, and 6) resulted in significantly higher titers relative to the respective single-dose cohorts by day 56 (Cohorts 1, 3, and 5, respectively; Fig. 2 A). Note that the highest dose level cohort 6 showed the highest titers compared to all other cohorts at day 56. All 28-day and 56-day cohort mean titers were similar to that of HCS (i.e., not significantly different) demonstrating relevance to natural immunity. The frequencies of seroconversion of the 22.5, 45, and 90 µg cohorts at day 28 were 70%, 90%, and 100%, respectively, which increased to 100% in all the respective two-dose cohorts 2, 4, and 6 by day 56 (Fig. 2 A). A similar response profile among cohorts and HCS was demonstrated with mean potency of titers at day 56 to inhibit binding of recombinant human ACE2 to recombinant SP/RBD (i.e., % inhibition values at 40x dilution; Fig. 2 B), that showed strong correlations with the individual subject’s respective IgG titer (i.e., ID50 vs. Anti-SP/RBD titer; Fig. 2 C). In addition, IgG titer isotyping demonstrated the favored Th1 response in each cohort on days 28 and 56 (Fig. 2 D).

To address whether the wild-type SP/RBD antigenic sequence of AKS-452 (i.e., that of the original SARS-CoV-2 Washington strain, USA-WA1/2020) induced titers that bound mutant SP/RBD epitopes of the currently known SARS-CoV-2 variant strains, a series of mutant SP/RBD ELISAs were used to evaluate each subject’s sera in addition to HCS samples to bind such mutant SP/RBD sequences (Fig. 3 A). All day 56 sera substantially bound each mutant SP/RBD in which most titers against SP/RBD mutants were similar to or within 3-fold less than those against the original Washington strain (Fig. 3 A and B; see Table S5 for individual cohort means). In addition, mean titers of all two-dose cohorts (i.e., cohorts 2, 4, and 6) were significantly higher than those of the one-dose cohorts (i.e., cohorts 1, 3, and 5), and most two-dose mean titers were significantly higher than that of HCS (Fig. 3 A). While the mean relative mutant SP/RBD titers among all six cohorts demonstrates the relationship to WT titers (Fig. 3 B), it should be noted that such 0- to 2.5-fold differences among the particular ELISAs could, in part, be a reflection of differences in SP/RBD mutant protein production quality.

Fig. 3.

AKS-452 Phase 1 study mutant SP/RBD immunogenicity. Serum samples obtained on Day 56 of initial vaccine dose and human convalescent sera (HCS) were assessed for titers of IgG binding to different mutant SARS-CoV-2 SP/RBD recombinant proteins via ELISA presented via combined cohorts of one vs. two doses (A). Statistical comparison of group means within a particular SP/RBD variant ELISA was performed with the 2-tailed t-test using unequal variance (GraphPad Prism). (B) Ratios of mutant/wild-type (WT, Washington) strain titers are presented in which the mean ratios of each of the 6 cohorts were used to calculate the grand mean and SEM for each relative mutant titer.

3.4. Live virus neutralization assay

Serum samples collected at day 56 significantly inhibited wild-type (Washington), alpha variant, and delta variant live virus from infecting live VERO E6 cells via the Plaque Reduction Neutralization Test at a 1:40 dilution (Fig. 4 ). In all cases, the extent of inhibition by the two-dose cohorts with 45 µg (Cohort 4) and 90 µg (Cohort 6) dose levels was similar to those obtained for the respective HCS samples, and that inhibition by all two-dose cohorts (i.e., cohorts 2, 4, and 6) was significantly greater than those of the one-dose cohorts (i.e., cohorts 1, 3, and 5) (see Fig. 4 for specific statistical comparisons).

Fig. 4.

AKS-452 Phase 1 study mutant SP/RBD immunogenicity and viral neutralization. Serum samples obtained on Day 56 of initial vaccine dose and human convalescent sera (HCS) were assessed for % neutralization (at 1:40 dilution of serum) of wild-type (Washington) and mutant (alpha and delta) live virus strains to infect live VERO E6 cells via the Plaque Reduction Neutralization Test. Statistical comparison of group means within a particular SP/RBD variant assay was performed with the 2-tailed t-test using unequal variance (GraphPad Prism). *denotes p < 0.05; all cohort means within a viral strain were significantly different from the respective HCS mean (p < 0.05) unless otherwise denoted by the “not significant” designation, ns.

4. Discussion

The overall safety assessment of AKS-452 in this 60-subject phase I clinical study showed limited side-effects in which no SAEs were attributable to vaccine dosing, and only a few mild AEs were associated with dosing that were comparable to or less than those of other registered COVID-19 vaccines [19]. No laboratory assessment abnormalities were observed. A 100% seroconversion rate was observed in all cohorts after two doses, and a dose-dependent seroconversion of 90% to 100% was observed at day 56 after a single dose, providing a viable option for further development of single-dose strategies. Levels of anti-SP/RBD IgG titers and inhibitory potencies were higher after two-dose regimens relative to those after the respective single-dose regimens, although all were within the range of convalescent sera. Indeed, convalescent sera titers and potencies have been strongly associated with protection from SARS-CoV-2 infection [20]. In addition, IgG- and ACE2-SP/RBD binding titers correlated well, demonstrating that use of either is expected to generate accurate immunogenicity assessment in the phase II study. Importantly, the Th1-type response induced by AKS-452 is consistent with the protective responses of currently Emergency Use Authorization-registered vaccines [21]. An important feature of the antigenic component of AKS-452, the RBD of the SP of the original SARS-CoV-2 Washington strain (USA-WA1/2020), has the strong capacity to induce titers focused on only this important binding domain of the virus, and not irrelevant binding epitopes that may facilitate the known liability of ADE [22]. In addition, this epitope-focused approach provides reactivity to mutant SP/RBD epitopes of currently known SARS-CoV-2 variant strains, supporting the expectation that AKS-452 could provide protection against other viral variants that must, by definition, use such RBD to achieve significant infection [23]. Indeed, AKS-452 can induce strong neutralization titers against live virus of the Washington, alpha, and delta variants, resulting in neutralizing levels similar to those induced by COVID-19 infection (i.e., HCS).

Based on the clean safety profile with respect to the one- and two-dose regimens, the 100% seroconversion rates, and inhibitory potencies consistent with that of HCS, such parameters will be considered in the statistical assessment to derive the study population required for phase II. Successful completion of the phase I and II trials in addition to a sufficient scale-up of the GMP manufacturing process will enable production of a sufficiently large quantity of doses for the phase III registration study and the future wide-scale vaccine treatment of the world population with AKS-452 in ISA 720. Akston’s current estimates indicate that a single 2,000 L bioreactor production train run could yield enough material for such an expected 45 µg dose of drug substance to treat approximately 100 million people receiving a single dose. A 2,000L bioreactor production train running ten times per year would therefore supply over 1 billion doses of AKS-452 at 45 µg per dose, creating an abundant vaccine resource world-wide including low- and middle-income countries. The prementioned manufacturing capacity is extremely significant and far surpasses the production throughput and costs of the other viral-based, nucleic acid-based, and full-length recombinant SP subunit-based vaccines. The potency (including strong neutralization against the alpha and delta variants), manufacturability, stability at easily achievable temperatures, and mechanism-of-action of the AKS-452 Fc-fusion protein formulated with adjuvant, therefore, offer an opportunity to immunize billions of people globally to maintain high levels of neutralizing anti-SP/RBD Ab titers throughout the population, regardless of COVID-19 status; i.e., boosting of those with prior SARS-CoV-2 infection or of those who received a prior vaccination.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Yester F. Janssen: Investigation, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. Eline A. Feitsma: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Hendrikus H. Boersma: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. David G. Alleva: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Data curation. Thomas M. Lancaster: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology. Thillainaygam Sathiyaseelan: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology. Sylaja Murikipudi: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology. Andrea R. Delpero: Investigation. Melanie M. Scully: Investigation. Ramya Ragupathy: Investigation. Sravya Kotha: Investigation. Jeffrey R. Haworth: Investigation. Nishit J. Shah: Investigation. Vidhya Rao: Investigation. Shashikant Nagre: Investigation. Shannon E. Ronca: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Freedom M. Green: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Ari Aminetzah: Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition. Frans Sollie: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. Schelto Kruijff: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Maarten Brom: Writing – review & editing. Gooitzen M. van Dam: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition. Todd C. Zion: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: The following authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: the following authors were employed by and received monetary compensation from Akston Biosciences, Inc.: DGA, ARD, MMS, SM, RR, EKG, TS, SK, JRH, NJS, VR, SN, TML, TZ. No other authors were personally compensated by Akston Biosciences.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgement

The infrastructure and material support from the Department of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging as well as the pharmaceutical support from the staff at the Department of Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology are greatly acknowledged. We would like to thank in particular: prof Rudi Dierckx, Gerda Bakker, prof Debbie van Baarle, prof Bert Niesters, Roelof Bekkema, Anouk Bos, and Janneke Holthuis.

Funding statement

This research was not funded by any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.01.043.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.University JH. COVID-19 Dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University;https://www.covidtracker.com/.

- 2.Heaton P.M. The Covid-19 Vaccine-Development Multiverse. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(20):1986–1988. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe2025111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karnik M., Beeraka N.M., Uthaiah C.A., Nataraj S.M., Bettadapura A.D.S., Aliev G., et al. A Review on SARS-CoV-2-Induced Neuroinflammation, Neurodevelopmental Complications, and Recent Updates on the Vaccine Development. Mol Neurobiol. 2021;58(9):4535–4563. doi: 10.1007/s12035-021-02399-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ramasamy M.N., Minassian A.M., Ewer K.J., Flaxman A.L., Folegatti P.M., Owens D.R., et al. Safety and immunogenicity of ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine administered in a prime-boost regimen in young and old adults (COV002): a single-blind, randomised, controlled, phase 2/3 trial. Lancet. 2020;396(10267):1979–1993. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32466-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhu F.-C., Guan X.-H., Li Y.-H., Huang J.-Y., Jiang T., Hou L.-H., et al. Immunogenicity and safety of a recombinant adenovirus type-5-vectored COVID-19 vaccine in healthy adults aged 18 years or older: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2020;396(10249):479–488. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31605-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bos R., et al. Ad26 vector-based COVID-19 vaccine encoding a prefusion-stabilized SARS-CoV-2 Spike immunogen induces potent humoral and cellular immune responses. NPJ Vaccines. 2020;5:91. doi: 10.1038/s41541-020-00243-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thompson M.G., Burgess J.L., Naleway A.L., Tyner H.L., Yoon S.K., Meece J., et al. Interim Estimates of Vaccine Effectiveness of BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273 COVID-19 Vaccines in Preventing SARS-CoV-2 Infection Among Health Care Personnel, First Responders, and Other Essential and Frontline Workers — Eight U.S. Locations, December 2020–March 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(13):495–500. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7013e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Verbeke R., Lentacker I., De Smedt S.C., Dewitte H. The dawn of mRNA vaccines: The COVID-19 case. J Control Release. 2021;333:511–520. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2021.03.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gao Q., Bao L., Mao H., Wang L., Xu K., Yang M., et al. Development of an inactivated vaccine candidate for SARS-CoV-2. Science. 2020;369(6499):77–81. doi: 10.1126/science.abc1932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xia S., Zhang Y., Wang Y., Wang H., Yang Y., Gao G.F., et al. Safety and immunogenicity of an inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine, BBIBP-CorV: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 1/2 trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21(1):39–51. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30831-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baden L.R., El Sahly H.M., Essink B., Kotloff K., Frey S., Novak R., et al. Efficacy and Safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(5):403–416. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2035389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Organization WH. Status of COVID-19 Vaccines within WHO EUL/PQ evaluation process. WHO Guidance Document; 2021. May 18th, 2021.

- 13.Ewer K., Sebastian S., Spencer A.J., Gilbert S., Hill A.V.S., Lambe T. Chimpanzee adenoviral vectors as vaccines for outbreak pathogens. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2017;13(12):3020–3032. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2017.1383575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park K.S., Sun X., Aikins M.E., Moon J.J. Non-viral COVID-19 vaccine delivery systems. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2021;169:137–151. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2020.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alleva D.G., Delpero A.R., Scully M.M., Murikipudi S., Ragupathy R., Greaves E.K., et al. Development of an IgG-Fc fusion COVID-19 subunit vaccine, AKS-452. Vaccine. 2021;39(45):6601–6613. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.09.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aucouturier J., Dupuis L., Deville S., Ascarateil S., Ganne V. Montanide ISA 720 and 51: a new generation of water in oil emulsions as adjuvants for human vaccines. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2002;1(1):111–118. doi: 10.1586/14760584.1.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ko E.-J., Kang S.-M. Immunology and efficacy of MF59-adjuvanted vaccines. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2018;14(12):3041–3045. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2018.1495301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park J.G., et al. Rapid in vitro assays for screening neutralizing antibodies and antivirals against SARS-CoV-2. J Virol Methods. 2021;287 doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2020.113995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu Q., Dudley M.Z., Chen X., Bai X., Dong K., Zhuang T., et al. Evaluation of the safety profile of COVID-19 vaccines: a rapid review. BMC Med. 2021;19(1) doi: 10.1186/s12916-021-02059-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khoury D.S., Cromer D., Reynaldi A., Schlub T.E., Wheatley A.K., Juno J.A., et al. Neutralizing antibody levels are highly predictive of immune protection from symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Med. 2021;27(7):1205–1211. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01377-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sadarangani M., Marchant A., Kollmann T.R. Immunological mechanisms of vaccine-induced protection against COVID-19 in humans. Nat Rev Immunol. 2021;21(8):475–484. doi: 10.1038/s41577-021-00578-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yahi N., Chahinian H., Fantini J. Infection-enhancing anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies recognize both the original Wuhan/D614G strain and Delta variants. A potential risk for mass vaccination? J Infect. 2021;83(5):607–635. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2021.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cevik M., Grubaugh N.D., Iwasaki A., Openshaw P. COVID-19 vaccines: Keeping pace with SARS-CoV-2 variants. Cell. 2021;184(20):5077–5081. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.