Highlights

-

•

Atrial fibrillation increases the risk of all primary and secondary outcomes after TAVR/TAVI.

-

•

NOAF is associated with a higher risk of 30-day mortality, stroke, and extended LOS after TAVR/TAVI.

-

•

Pre-AF is associated with a higher risk of AKI and early bleeding episodes after TAVR/TAVI.

Keywords: TAVI, TAVR, NOAF, Atrial fibrillation, Aortic stenosis

Abbreviations: AKI, acute kidney injury; CI, confidence interval; LOS, length of stay; NOAF, new-onset atrial fibrillation; OR, odds ratio; pre-AF, pre-existing atrial fibrillation; TAVI, transcatheter aortic valve implantation; TAVR, transcatheter aortic valve replacement

Abstract

Patients with aortic stenosis who undergo transcatheter aortic valve replacement/transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVR/TAVI) experience a high incidence of pre-existing atrial fibrillation (pre-AF) and new-onset atrial fibrillation (NOAF) post-operatively. This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to update current evidence concerning the incidence of 30-day mortality, stroke, acute kidney injury (AKI), length of stay (LOS), and early/late bleeding in patients with NOAF or pre-AF who undergo TAVR/TAVI. PubMed, Google Scholar, JSTOR, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science were searched for studies published between January 2012 and December 2020 reporting the association between NOAF/pre-AF and clinical complications after TAVR/TAVI. A total of 15 studies including 158,220 adult patients with TAVI/TAVR and NOAF or pre-AF were identified. Compared to patients in sinus rhythm, patients who developed NOAF had a higher risk of 30-day mortality, AKI, early bleeding events, extended LOS, and stroke after TAVR/TAVI (odds ratio [OR]: 3.18 [95% confidence interval [CI] 1.58, 6.40]) (OR: 3.83 [95% CI 1.18, 12.42]) (OR: 1.70 [95% CI 1.05, 2.74]) (OR: 13.96 [95% CI, 6.41, 30.40]) (OR: 2.51 [95% CI 1.59, 3.97], respectively). Compared to patients in sinus rhythm, patients with pre-AF had a higher risk of AKI and early bleeding episodes after TAVR/TAVI (OR: 2.43 [95% CI 1.10, 5.35]) (OR: 17.41 [95% CI 6.49, 46.68], respectively). Atrial fibrillation is associated with a higher risk of all primary and secondary outcomes. Specifically, NOAF but not pre-AF is associated with a higher risk of 30-day mortality, stroke, and extended LOS after TAVR/TAVI.

1. Introduction

Transcatheter aortic valve replacement/implantation (TAVR/TAVI) is a percutaneous intervention that is used to treat aortic stenosis and improve cardiac function [1]. It is approved for patients with low-to-high surgical risk and valve-in-valve replacement of failed bioprosthetic valves [2]. The structural and functional cardiovascular changes facilitated by TAVR in patients with aortic stenosis effectively enhance hemodynamic performance [3]. Furthermore, TAVR provides a long-term treatment advantage by reducing trans-aortic gradients and increasing the effective orifice area. This leads to improved morbidity and all-cause mortality after TAVR [4].

Atrial fibrillation occurs in 33–44% of patients with TAVR and increases their risk of cardiovascular complications [5], [6]. Prior meta-analyses have reported the association of atrial fibrillation with increased risk of major bleeding, stroke, and mortality [7], [8]. The past studies did not stratify TAVR outcomes while differentiating NOAF from pre-AF. They also did not categorize TAVR risk factors or prognoses according to the type of atrial fibrillation.

This study aimed to update the findings of prior meta-analyses by exploring the clinical outcomes of patients with TAVI/TAVR and new-onset atrial fibrillation [NOAF] or pre-existing atrial fibrillation [pre-AF].

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

This study was designed following the PRISMA [Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis] recommendations [9]. Any valvular, non-valvular, paroxysmal, persistent, and permanent atrial fibrillation was considered pre-AF. NOAF was considered as atrial fibrillation occurring after TAVR intervention in patients without previously diagnosed atrial fibrillation.

2.2. Ethics statement

This study did not require informed consent or institutional review board approval.

2.3. Selection criteria/search strategy

Observational, prospective, retrospective and posthoc studies published between January 2012 and December 2020 were included. Two authors explored the target studies via Google Scholar, JSTOR, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science. The MeSH [medical subject headings] search terms included the following: “TAVR,” “TAVI,” “aortic stenosis,” “NOAF,” “30-day mortality,” “stroke,” “LOS,” “AKI,” “early bleeding,” and “late bleeding”. Studies that reported on the association between clinical outcomes and NOAF or pre-AF in patients with TAVR/TAVI were included. Further, the following inclusion parameters were considered during the screening process:

-

1.

The outcome data warranted correlation with pre-AF or NOAF

-

2.

The clinical outcomes included any of the following: 30-day mortality, stroke, AKI, LOS, early bleeding, and late bleeding.

The citations and references were extensively reviewed for the included studies and the validity of their clinical endpoints was confirmed after examining their statistical methods. Two authors independently evaluated the evidence levels of the included studies, and one author investigated the risk of bias/publication bias by constructing the funnel plots from the outcome data. Clinical outcomes, study design, sample size, interventions, and inferences, and were categorically extracted and listed in Table 1. Table 2 provided the baseline characteristics of the patients, including EuroSCORE II or STS. Fig. 1a indicates the screening process for extracting the studies of interest.

Table 1.

Summary of sample size, method, interventions, findings, and evidence-levels of included studies.

| Study | Sample Size | Method | Intervention | Inference | Evidence-Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amat-Santos et al. (2012) | 138 subjects | Observation (multicenter) study | Assessment of NOAF concerning its prognostic value, outcomes, predictive factors, and incidence in the setting of TAVI | NOAF substantially increased the incidence of systemic embolism (p = 0.047) and stroke (13.6% vs. 3.2%; p = 0.021) after TAVI | II |

| Biviano et al. (2016)/PARTNER | 1,879 patients | Prospective trial (post-hoc analysis) | Clinical evaluation and assessment of echocardiogram/electrocardiogram at baseline discharge and 30-days, 6 months, and one year after TAVR | Patients who developed atrial fibrillation after sinus rhythm at discharge experienced all-cause mortality at thirty days and one-year (HR: 3.41, 95% CI 1.78, 6.54) (HR: 2.14, 95% CI 1.45, 3.10). The presence of atrial fibrillation at baseline (HR: 2.14, 95% CI 1.45, 3.10) and discharge (HR: 1.88, 95% CI 1.50, 2.36) proved to be the predictor for one-year mortality. Patients with TAVR and reduced ventricular response and atrial fibrillation at discharge showed increased one-year all-cause mortality (HR: 0.74, 95% CI 0.55, 0.99) | II |

| Chopard et al. (2015)/FRANCE-2 | 3,933 subjects | Prospective multicenter study | Assessment of prognostic value of NOAF, predictive attributes, baseline characteristics, and long-term outcomes in patients following TAVI | Patients with pre-existing atrial fibrillation experienced a higher incidence of all-cause mortality and rehospitalization as compared to patients who developed NOAF after TAVI (p < 0.001) NOAF substantially increased the incidence of post-procedural hemorrhagic events in TAVI scenarios (p < 0.001) NOAF added to the incidence rate of combined efficacy endpoint and all-cause mortality at one year in patients with TAVI (p = 0.02) |

II |

| Sannino et al. (2016) | 708 subjects | Retrospective cohort study | Assessment of prognostic outcomes of NOAF/pre-AF in patients with TAVI | patients with TAVI and pre-AF experienced a higher risk of one-year mortality (HR: 2.34, 95% CI 1.22, 4.48) (p = 0.010) | II |

| Stortecky et al. (2013) | 389 subjects | Prospective single-center trial | Assessment of the influence of atrial fibrillation on the incidence of mortality, stroke, acute kidney injury, and late bleeding episodes in patients with TAVI | patients with TAVI and atrial fibrillation experienced a greater incidence of one-year all-cause mortality as compared to patients without atrial fibrillation (HR: 2.36, 95% CI 1.43, 3.90) patients with TAVI with or without atrial fibrillation experience a high risk for life-threatening bleeding and stroke (HR: 1.37, 95% CI 0.86, 2.19) (HR: 0.76, 95% CI 0.23, 1.96) |

II |

| Tarantini et al. (2016)/SOURCE-XT | 2,688 subjects | Prospective multicenter trial | Assessment of bleeding events, cardiac death, and all-cause mortality in patients with TAVR and NOAF | NOAF elevated the incidence stroke in patients with TAVR within a tenure of 1–2 years (HR: 1.96, 95% CI 1.39, 2.76) (p = 0.0001) | II |

| Yankelson et al. (2014) | 380 subjects | Retrospective cohort study | Assessment of TAVI-related procedural complications in the context of NOAF versus pre-AF | Baseline atrial fibrillation significantly elevated mortality incidence in patients with TAVI (HR: 2.2, 95% CI 1.3, 3.8) (p = 0.003) | II |

| Nombela-Franco et al. (2012) | 1061 subjects | Retrospective cohort study | Assessment of prognostic value, predictive factors, and timing of cerebrovascular episodes in patients with TAVI | NOAF was associated with increased risk of subacute stroke (occurring 1–30 days post-TAVR) (OR: 2.76, 95 %CI 1.11, 6.83) Chronic AF in TAVR was associated with increased risk of late stroke (occurring > 30 days after TAVR) (HR: 2.84, 95% CI 1.46, 5.53) |

II |

| Mentias et al. (2019) | 72,660 subjects | Retrospective cohort study | Medicare inpatient claims data were used to assess the association of NOAF and long-term outcomes in patients with TAVR. Follow-up was 73,732 person-years. | NOAF in patients with TAVR was associated with increased risk of mortality compared with those without AF (HR: 2.07, 95% CI 1.91, 2.20) (p < 0.01) or pre-AF (HR: 1.35, 95% CI 1.26, 1.45) (p < 0.01) Compared to pre-AF, NOAF was also associated with increased risk of bleeding (HR: 1.66; 95% CI 1.48, 1.86), stroke (HR: 1.92, 95% CI 1.63, 2.26), and heart failure (HR: 1.98, 95% CI 1.81, 2.16) |

II |

| Maan et al. (2015) | 137 subjects | Retrospective cohort study | Assessment of the influence of AF on a composite of all-cause death, stroke, vascular complications, and hospitalizations within 1 month after TAVR | Pre-existing AF in patients with TAVR was associated with increased risk of death, vascular complications, and readmission within 1 month (OR: 2.60, 95% CI 1.22, 5.54) NOAF was strongly associated with the trans-apical approach in patients with TAVR (OR: 5.05, 95% CI 1.40, 18.20) |

|

| Yoon et al. (2019) | 347 subjects | Prospective cohort trial | Assessment of clinical outcomes of NOAF in patients with TAVI | Patients with TAVI and NOAF experienced a high predisposition for systemic embolism and stroke at one year (HR: 3.31, 95% CI 1.34, 8.20) | II |

| Patil et al. (2020) | 72, 666 subjects hospitalized for TAVR | Retrospective cohort study | National Inpatient Sample database was queried to assess the association between atrial fibrillation and adverse outcomes in patients receiving TAVR. | Atrial fibrillation clinically correlated with increased risk of TIA/stroke (OR: 1.36, 95% CI 1.33, 1.78), acute kidney injury (OR: 1.54, 95% CI: 1.33, 1.78), and elevated average LOS (OR: 1.30, 95% CI: 1.06, 1.54). Atrial fibrillation did not increase the risk of inpatient mortality (OR: 1.09, 95% CI 0.81, 1.48) |

II |

| Zweiker et al. (2017) | 398 subjects | Retrospective cohort study | Assessment of predictors of 1-year mortality after TAVR. Clinical records were reviewed for diagnosis of baseline atrial fibrillation and NOAF | Compared to baseline sinus rhythm, baseline atrial fibrillation was associated with higher mortality at 1 year after TAVR (19.8% vs. 11.5%, p = 0.02) NOAF was associated with increased risk of hospital readmissions (62.5 vs. 34.8%, p = 0.04) (HR: 5.86, 95% CI 1.04, 32.94), excluding mortality |

II |

| Barbash et al. (2015) | 371 subjects | Post-hoc analysis | Assessment of clinical impact, post-procedural incidence, and baseline characteristics concerning atrial fibrillation in patients with TAVI | NOAF correlated with transapical access during TAVI (OR: 4.96, 95% CI 1.9, 13.2) and procedural hemodynamic instability (OR: 9.3, 95% CI 1.5, 59) | II |

| Okuno et al. (2020) | 465 subjects | Retrospective assessment of a prospective trial | Assessment of clinical outcomes of patients with TAVR and non-valvular or valvular atrial fibrillation | Valvular atrial fibrillation substantially increased the predisposition for disabling stroke or cardiovascular death after TAVR (HR: 1.77, 95% CI 1.07, 2.94) (p = 0.027) | II |

HR = hazard ratio; CI = confidence interval; LOS = length of stay; NOAF = new-onset atrial fibrillation; OR = odds ratio; pre-AF = pre-existing atrial fibrillation; TAVI = transcatheter aortic valve implantation; TAVR = transcatheter aortic valve replacement.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of patients with pre-existing/new-onset atrial fibrillation.

| Study | Amat-Santos et al. (2012) | Biviano et al. (2016)/PARTNER | Chopard et al. (2015)/FRANCE-2 | Sannino et al. (2016) | Stortecky et al. (2013) | Tarantini et al. (2016)/SOURCE-XT | Yankelson et al. (2014) | Nombela-Franco et al. (2012) | Mentias et al. (2019) | Maan et al. (2015) | Yoon et al. (2019) | Patil et al. (2020) | Zweiker et al. (2017) | Barbash et al. (2015) | Okuno et al. (2020) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yrs | 79 ± 8 | 86.1 [81.9,89.3] | 82.6 ± 7.4 | 81.9 ± 7.8 | 82.5 ± 5.8 | 81.6 ± 5.8 | 83.0 (5.6) | 81 ± 8 | 81.9 (8.1) | 84.18 ± 6.83 | 79.6 ± 5.1 | 82 (6.9) | 82 (78–85) | 84 ± 7 | 81.71 ± 5.99 |

| Male | 54 (39.1) | 57.7 | – | 341 (54.4%) | – | – | – | 538 (50.7) | 53 | 65 (47%) | 23 (46%) | 1,745 [55] | – | 83 (58%) | – |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 27 ± 5 | 25.2 [22.5,29.3] | 25.9 ± 5.1 | 27.9 ± 12.9 | 26.1 ± 5.1 | 26.7 ± 5.0 | 27.2 ± 5.1 | 26.0 ± 5.0 | – | 26.70 5.90 | 23.8 ± 3.7 | – | 25 (23–28) | – | 25.53 ± 4.81 |

| Diabetes | 52 (37.7) | 36 | 710 (24.7) | 265 (40.1%) | 105 (27) | 219 (32.0%) | 124 (32.6%) | 312 (29.4) | 37.3 | 47 (34%) | 18 (36%) | – | 117 (29) | 43 (30%) | 28 (31.5) |

| Dyslipidemia | 114 (82.6) | – | – | 481 (69.6%) | – | 334 (48.8%) | 294 (77.4%) | – | – | 95 (69%) | 28 (56%) | – | – | – | – |

| Hypertension | 126 (91.3) | 92.8 | 2,011 (70.0) | 574 (82.2%) | 303 (78) | 550 (80.3%) | 331 (87.1%) | 790 (74.5) | 88.1 | 109 (80%) | 45 (90%) | – | 330 (83) | 135 (94%) | 78 (87.6) |

| NYHA functional class I–II | 23 (16.7) | 4.9 | – | – | 109 (28) | 134 (19.6%) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| NYHA functional class III–IV | 115 (83.3) | 46.8–48.3 | – | – | 49 (13) | 550 (80.4%) | – | 886 (83.5) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Coronary artery disease | 90 (65.2) | – | 1,394 (48.5) | 475 (68.2%) | 238 (61) | – | 214 (56.3%) | 686 (64.7) | 24 | 99 (72%) | – | – | 283 (71) | 81 (84%) | 51 (57.3) |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 48 (34.8) | 23.1 | – | – | 64 (16) | – | 63 (16.6%) | 377 (35.6) | – | – | 3 (6%) | 11 [0] | 3 (2) | 23 (17%) | – |

| Previous PCI | 55 (39.9) | – | – | – | 94 (24) | 198 (28.9%) | 161 (42.4%) | – | – | 51 (37%) | 13 (26%) | – | 137 (34) | 40 (29%) | – |

| Prior coronary artery bypass grafting | 52 (37.7) | – | 515 (17.9) | 296 (44.6%) | 72 (19) | 106 (15.5%) | 17.6 (6.7%) | 320 (30.2) | – | 55 (40%) | 4 (8%) | – | 60 (15) | 43 (31%) | – |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 31 (22.5) | – | – | 124 (19.5%) | 30 (8) | – | – | 191 (18.1) | – | 25 (18%) | – | – | – | – | 11 (12.4) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 53 (38.4) | – | 793 (27.6) | 225 (34.0%) | – | 151 (22.1%) | 29 (7.6%) | 278 (26.2) | 26.5 | 42 (31%) | 4 (8%) | – | – | 42 (31%) | – |

| COPD (%) | 39 (28.3) | 45.1 | 650 (22.6) | 132 (20.8%) | – | 156 (22.8%) | 18.4 (70%) | 310 (29.2) | 31.1 | 39 (28%) | – | – | 63 (16) | 53 (37%) | – |

| Creatinine, mg/dl | 1.18 (0.88–1.61) | – | – | – | – | – | 51.3 ± 19.8 | – | – | 1.33 ± 0.47 | – | – | 98 (80–123) | – | – |

| eGFR < 60 ml/min | 89 (64.5) | – | – | – | – | – | – | 60.1 ± 27.8 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Logistic EuroSCORE | 21.7 ± 15.7 | – | 20.8 ± 13.6 | – | 24.3 ± 14.2 | 22.4 ± 13.4 | 24.3 ± 14.1 | – | – | 14.33 ± 12.24 | 20.2 ± 13.8 | – | 13.3 (7.8–23.8) | – | – |

| STS-PROM score, % | 7.4 ± 4.8 | 11.1 [9.6,13.5] | 13.6 ± 11.4 | – | 6.8 ± 5.3 | 8.5 ± 6.7 | – | 6.5 (4.3–9.7) | – | 6.88 ± 3.82 | 5.2 ± 3.2 | – | 6.3 (3.8–9.6) | – | 6.75 ± 3.92 |

| CHADS2 score | 3 (3–4) | 5.7 ± 1.3 | – | – | – | – | 2.5 ± 0.9 | 2.9 ± 1.2 | 4.6 (1.2) | – | 4.4 ± 1.2 | – | 5 (5–6) | – | 2.75 ± 1.05 |

| Severely calcified or porcelain aorta | 42 (30.4) | – | – | – | – | 38 (5.6%) | – | 193 (18.4) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Frailty | 24 (17.4) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 13 (9.4) | 47.8 | 639 (22.2) | – | – | – | – | – | 10.7 | 38 (28%) | 17 (34%) | – | – | – | – |

| Mean aortic gradient, mm Hg | 43 ± 17 | – | – | 44.1 ± 13.6 | 44.2 ± 16.8 | – | 47.3 ± 15 | 43 ± 16 | – | 50.73 ± 16.29 | 55.5 ± 18.3 | – | 45 (32–60) | – | – |

| Aortic valve area, cm2 | 0.6 (0.5–0.7) | – | 0.8 | 0.68 ± 0.18 | 0.6 ± 0.2 | – | 0.71 ± 0.19 | 0.66 ± 0.19 | – | 0.60 ± 0.13 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | – | 0.53 (0.41–0.66) | 0.64 ± 0.11 | – |

| LVEF, % | 55 ± 14 | 55.0 [44.4,60.0] | – | 54.6 ± 13.0 | 51.9 ± 14.8 | – | 55.8 ± 7.8 | – | – | 55.29 ± 17.10 | 57.7 ± 9.5 | – | 303 | 52 ± 13 | 55 ± 15 |

| LVEF < 40 | 23 (16.7) | – | 197 (6.8) | – | – | – | – | 235 (22.1) | – | 32 (23%) | 0 | – | 41 (14) | – | – |

| Mitral regurgitation | 4 (2.9) | 3.4 | 48 (1.7) | – | – | 184 (27.3%) | – | – | – | 8 (6%) | 8 (16%) | – | – | 18 (14%) | 19 (26.4) |

| Left ventricular mass, g/m2 | 125.5 ± 36.4 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| LVEDD, mm | 46.9 ± 7.9 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 44.58 ± 7.14 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Left atrial size, mm | 44.7 ± 8.0 | – | 27 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 46.7 ± 9.3 | – | – | – | – |

| Left atrial size, indexed, mm/m2 | 26.4 ± 5.4 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Systolic pulmonary pressure, mm Hg | 43.5 ± 11.9 | 47.8 | 639 (22.2) | – | – | 230 (33.6%) | – | – | – | – | – | – | 45 (33–60) | 51 ± 19 | – |

| Procedural success | 129 (93.5) | – | 947 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Valve embolization | 1 (0.7) | – | – | – | – | – | – | 44 (4.1) | – | 4 (6%) | – | – | – | – | – |

| Need for hemodynamic support | 4 (2.9) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Major vascular complications | 13 (9.4) | – | – | – | – | – | – | 100 (9.4) | 1.6 | 2 (3%) | – | 167 [5] | – | – | – |

| Myocardial infarction | 0 | – | 8 (0.8) | – | – | 104 (15.2%) | – | – | – | 1 (1%) | – | – | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 (0.0) |

| Cerebrovascular event | 0 | – | 65 (6.5) | – | – | – | – | – | – | 4 (6%) | – | – | – | – | 5 (5.7) |

| Transient ischemic attack | 0 | – | – | – | 1 (0.4) | 29 (4.2%) | – | – | – | – | – | 99 [3] | – | – | 0 (0.0) |

| Stroke | 8 (5.8) | 26.7 | 263 (9.1) | 17 (2.4%) | 17 (4.8) | 71 (10.4%) | 38 (10%) | – | 4.3 | 2 (3%) | 7 (14%) | – | 2 (1) | – | 5 (5.7) |

| Death | 10 (7.3) | – | – | 21 (3.0%) | 77 (22.6) | – | – | – | – | 6/70 (9%) | – | – | 9 (5) | 15 (10.3%) | 4 (4.6) |

| frailty | – | 0.2 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Pacemaker status (%) | – | 17.9 | 340 (11.8) | – | – | 102 (14.9%) | 40 (10.5%) | – | 7 | 27 (20%) | – | 344 [11] | 29 (17) | – | – |

| Liver disease (%) | – | 3.2 | – | – | – | 18 (2.6%) | – | – | 2.6 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Rheumatic fever (%) | – | 1.5 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Renal disease (Cr ≥ 2) (%) | – | 17.7 | – | 345 (49.6%) | 268 (69) | – | – | – | 36.5 | – | 22 (44%) | 528 [17] | 7 (4) | 18 (13.8%) | 67 (75.3) |

COPD: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; LVEF: Left ventricular ejection fraction; eGFR: Estimated glomerular filtration rate; EuroSCORE: The European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation Score; STS: Short-term risk calculator; BMI: Body mass index.

Fig. 1.

Central Illustration a: Screening process for extracting the studies of interest.

2.4. Patient population

A total of 15 studies that enrolled 158,220 adult patients [>18 years of age] with TAVI/TAVR and NOAF/pre-AF were included in this systematic review and meta-analysis.

2.5. Clinical outcomes

The following primary clinical outcomes were considered for this systematic review/meta-analysis:

-

1.

30-day mortality

-

2.

Stroke

-

3.

Early bleeding

-

4.

Late bleeding

The secondary clinical outcomes included the following variables:

-

1.

Acute kidney injury [AKI]

-

2.

Length of stay [LOS]

2.6. Data analysis

A meta-analysis of the primary and secondary endpoints was performed by calculating the odds ratios [ORs] ] and 95% CIs [confidence intervals]. A random effect approach was used to configure forest plots for comparing the clinical outcomes in the setting of pre-AF, NOAF, and sinus rhythm [10]. RevMan 5.4 software [Cochrane, London, UK] was used to evaluate the outcome variables. The paired permutations considered NOAF/pre-AF as an intervention/study arm and sinus rhythm as the control arm. The Chi-squared, Tau-squared, and I-squared values indicated the heterogeneity of the study outcomes [11]. A heterogeneity score > 60% was used to investigate the variability of the reported results. Publication bias in the outcomes of included studies was assessed by the construction of funnel plots [12]. The pairwise assessment of the study outcomes guided the analysis of their clinical correlation with pre-AF/NOAF versus sinus rhythm. The quality of the selected studies reciprocated with their evidence levels. Additionally, the hazard ratios of the clinical outcomes of the included studies were examined in this systematic review [Table 1]. The statistical significance of the heterogeneity of the included studies was determined via two-tailed p-values [13]. The overall effect size [Z] indicated the magnitude/strength of the findings; however, its statistical significance relied on the respective p-values [14]. A p-value ≤ 0.05 was considered the standard parameter for determining the statistical significance of the study results.

3. Results

3.1. Clinical outcomes regarding new-onset atrial fibrillation

Seven studies indicated an elevated incidence of 30-day mortality in patients with aortic stenosis and TAVI/TAVR in the setting of NOAF [OR: 3.18 [95% CI 1.58, 6.40]] [Fig. 2a]. A p-value of 0.001 affirmed the statistical significance of the reported effect size of 3.25. The symmetrical forest plot negated the risk of publication bias in the reported findings [Fig. 2b]. The I-square value of 62% indicated the heterogeneity of the outcomes. However, the associated p-value of 0.007 negated the statistical significance of the reported heterogeneity.

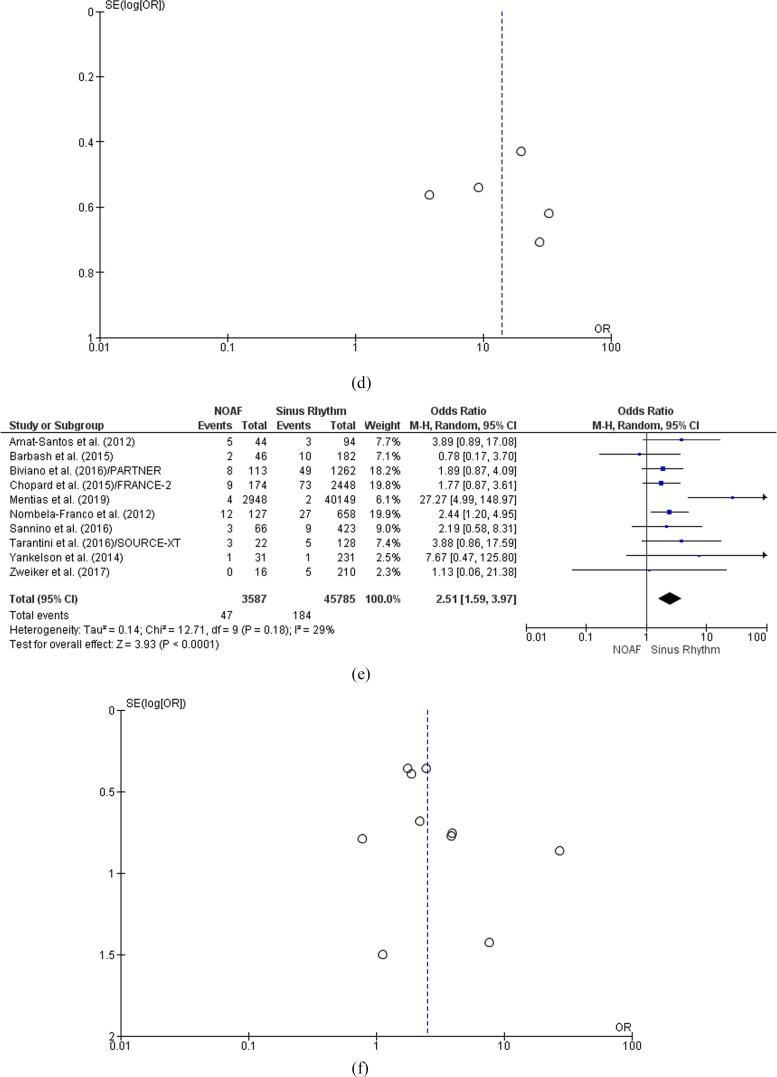

Fig. 2.

Clinical outcomes of patients with TAVI in the setting of NOAF a: 30-Day Mortality Forest plot. b: 30-Day Mortality Funnel plot; c: AKI Forest plot. d: AKI Funnel plot; e: Early Bleeding Forest plot; f: Early Bleeding Funnel plot AKI = acute kidney injury; NOAF = new-onset atrial fibrillation; TAVI = transcatheter aortic valve implantation.

Five studies affirmed the high incidence of AKI in patients with TAVR and NOAF as compared to patients in sinus rhythm [OR: 3.83 [95% CI 1.18, 12.42]] [Fig. 2c]. The p-value of 0.03 affirmed the statistical significance of the reported effect size of 2.23. The heterogeneity of findings was affirmed by a statistically significant I-square value of 89% [p < 0.00001]. The nearly symmetrical forest plot ruled out the risk of publication bias in the reported results [Fig. 2d].

Five studies confirmed the high incidence of early bleeding episodes in patients with TAVR and NOAF. This finding was supported by the odds ratio of 1.70 [95% CI 1.05, 2.74] [p = 0.03, Z = 2.18] [Fig. 2e]. The I-square value of 46% ruled out the heterogeneity in the reported outcomes; however, this finding proved statistically insignificant based on the p-value of 0.08. The nearly symmetrical funnel plot negated the risk of publication bias in the reported results [Fig. 2f].

Two studies provided statistically insignificant results related to the occurrence of late bleeding episodes in patients with TAVI and NOAF. The reported odds ratio of 1.29 [95% CI 0.95, 1.75] lacked statistical significance based on the p-value of 1.63 for the reported effect size [Z = 1.63] [Fig. 3a]. The I-square value of 20% revealed the absence of heterogeneity in the reported findings; however, the p-value of 0.29 did not affirm the variability of the outcome. The asymmetrical funnel plot further indicated the risk of publication bias in the findings related to late bleeding events [Fig. 3b].

Fig. 3.

Clinical outcomes of patients with TAVR in the setting of NOAF a: Late Bleeding Forest plot. b. Late Bleeding Funnel plot; c: LOS Forest plot; d: LOS Funnel plot; e: Stroke Forest plot; f: Stroke Funnel plot LOS = length of stay; NOAF = new-onset atrial fibrillation; TAVR = transcatheter aortic valve replacement.

Five studies revealed confirmed the clinical correlation between NOAF and extended LOS in TAVR [OR: 13.96 [95% CI, 6.41, 30.40] ] [Z = 6.64] [p < 0.00001] [Fig. 3c]. The statistically significant I-square value of 60% [p = 0.04] affirmed the heterogeneity in the reported findings regarding LOS. The symmetrical funnel plot ruled out the risk of publication bias in LOS-related findings [Fig. 3d].

The outcomes from eight studies revealed significant effect sizes confirming the high incidence of stroke episodes in patients with TAVI and NOAF [OR: 2.51 [95% CI 1.59, 3.97] ] [p < 0.0001] [Z = 3.93] [Fig. 3e]. The I-square outcome of 29% ruled out the heterogeneity in the reported findings; however, this result lacked statistical significance based on the p-value of 0.18. The symmetrical funnel plot negated the risk of publication bias in stroke-related results [Fig. 3f].

3.2. Clinical outcomes regarding pre-existing atrial fibrillation

Two studies indicated the high incidence of 30-day mortality in patients with TAVI/TAVR and pre-AF. The reported odds ratio of 1.80 [95% CI 0.92, 3.50], however, lacked statistical significance due to the reported p-value of 0.08 for the overall effect size [Z) of 1.73 [Fig. 4a]. The statistically significant I-square value of 82%, however, confirmed the heterogeneity of the reported results [p = 0.0008]. The symmetrical funnel plot ruled out the probability of publication bias in the results related to 30-day mortality in TAVI scenarios [Fig. 4]b].

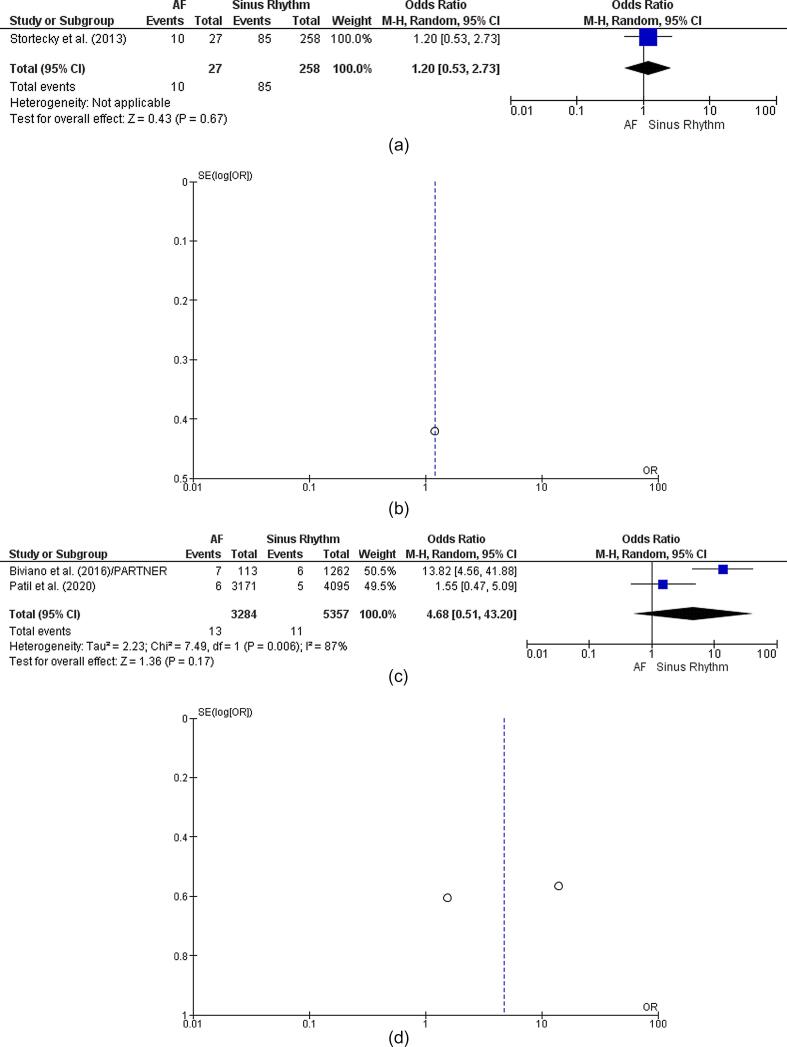

Fig. 4.

Clinical outcomes of patients with TAVI in the setting of pre-AF. 4a: 30-Day Mortality Forest plot; 4b: 30-Day Mortality Funnel plot; 4c: AKI Forest plot; 4d: AKI Funnel plot; 4e: Early Bleeding Forest plot; 4f: Early Bleeding Funnel plot. AKI = acute kidney injury; pre-AF = pre-existing atrial fibrillation; TAVI = transcatheter aortic valve implantation.

Three studies showed a high incidence of AKI episodes in patients with TAVI and pre-AF [OR: 2.43 [95% CI 1.10, 5.35] ] [p = 0.03] [Z = 2.21] [Fig. 4c]. The statistically significant I-square value of 86% confirmed the heterogeneity in the reported results [p = 0.0007]. The nearly symmetrical funnel plot negated the risk of publication bias in AKI-related results [Fig. 4d].

One study provided a statistically significant OR of 17.41 [95% CI 6.49, 46.68] [p = 0.03] [Z = 2.14] confirming the high risk of early bleeding events in TAVR/TAVI cases [Fig. 4e]. The finding proved heterogeneous as compared to the outcomes of the other two studies that revealed no effect of pre-AF on early bleeding episodes in patients with TAVI. The nearly symmetrical funnel plot ruled out the risk of publication bias in findings related to early bleeding in TAVR/TAVI scenarios [Fig. 4f].

The outcome of one study revealed statistically insignificant findings affirming the absence of late bleeding episodes in patients with TAVI and pre-AF [OR: 1.20 [95% CI 0.53, 2.73] [p = 0.67] [Fig. 5a]. The symmetrical/coherent funnel plot, however, negated publication bias in the reported outcome [Fig. 5b].

Fig. 5.

Clinical outcomes of patients with TAVR in the setting of pre-AF. a: Late Bleeding Forest plot. b: Late Bleeding Funnel plot; c: LOS Forest plot; d: LOS Funnel plot; e: Stroke Forest plot; f: Stroke Funnel plot. LOS = length of stay; pre-AF = pre-existing atrial fibrillation; TAVR = transcatheter aortic valve replacement.

Two studies revealed statistically insignificant OR related to the length of patient stay based on pre-AF in TAVI/TAVR scenarios [OR: 4.68 [95% CI 0.51, 43.20]] [Z = 1.36] [p = 0.17] [Fig. 5c]. The statistically significant I-square finding of 87% affirmed substantial heterogeneity in the reported outcomes [p = 0.006]. The symmetrical funnel plot negated the probability of publication bias in findings based on the LOS of patients with TAVR [Fig. 5d].

Two studies revealed statistically significant findings concerning the incidence of stroke events in patients with TAVR and pre-AF [OR: 1.71 [95% CI 0.67, 4.38] ] [Z = 1.12] [p = 0.26] [Fig. 5e]. However, the statistically significant I-square finding of 89% confirmed a high level of heterogeneity in the reported results [p = 0.00001]. The nearly symmetrical funnel plot negated the risk of publication bias in findings based on stroke episodes [Fig. 5f].

4. Discussion

This meta-analysis showed that NOAF was associated with an increased risk of 30-day mortality, AKI, early bleeding, stroke, and extended LOS in patients with TAVI/TAVR [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29] [Fig. 1]. The findings also showed that pre-AF was associated with an increased risk of AKI and early bleeding episodes in patients undergoing TAVR/TAVI. NOAF did not independently contribute to the late bleeding episodes in patients with TAVI. Pre-AF was not associated with an increase in 30-day mortality, late bleeding, stroke episodes, and increased LOS after TAVR.

This study builds on the findings of the meta-analysis by Mojoli et al. [2017] that attributed episodes of major bleeding, stroke, and mortality after TAVR/TAVI to the presence of atrial fibrillation [30]. We add to their findings by reporting the association of NOAF and increased risk of secondary outcomes of AKI and LOS, in addition to the primary outcomes of stroke, early bleeding, and increased LOS in patients with TAVI/TAVR. These findings also support the results from a previously reported meta-analysis that correlated NOAF after TAVI with 1–2-year follow-up visits, cardiovascular events, and mortality [31]. The results of the present study elevated the generalizability of previously reported meta-analysis findings that confirmed the role of NOAF in increasing mortality risk by 17.5% after TAVR [32]. Future studies should analyze the need for antiplatelet and anticoagulation therapies, as well as other medical interventions, to minimize the incidence of clinical complications in patients with TAVI and NOAF [33].

It is well known that NOAF after TAVR develops in the setting of inflammatory processes [34]. For instance, previous studies showed that hypertensive patients undergoing TAVI who receive diuretics experience a high incidence of NOAF and its subsequent clinical complications. Baseline patient characteristics affect the clinical course of NOAF, and can ultimately increase the risk of embolic events, stroke, and bleeding after TAVR [35]. The access site or approach for TAVI [trans-femoral, trans-subclavian, direct aortic, trans-carotid, and trans-apical] also influences the development and clinical outcomes of NOAF in the treated patients. Vascular access injuries in many clinical scenarios have also been known to increase the risk of NOAF-related stroke, bleeding, and mortality. Furthermore, cardiac conduction abnormalities that arise because of TAVR/TAVI also trigger clinical complications in the setting of NOAF [36]. Finally, NOAF has been found associated with an increased risk of cardiac tamponade and heart failure after TAVR.

5. Limitations

This systematic review/meta-analysis is not without limitations. First, the role of mechanical complications, including embolization/dislodgement and balloon post-dilation, and their impact on atrial fibrillation and its clinical complications after TAVI was not assessed. Second, the obtained results do not delineate the causative factors contributing to the progression of NOAF and its adverse manifestations in TAVI/TAVR scenarios. Third, the data from the retrospective and prospective studies concerning NOAF or pre-existing AF [including duration, AF burden, treatment, etc.) are not concrete and robust. The inclusion of retrospective and prospective studies in this study attributed to the unavailability of the randomized controlled trials concerning NOAF versus pre-existing AF outcomes after TAVR implantation. The inclusion of these mixed studies impacted the data interpretation and restricted the validity, reliability, and generalizability of the outcomes across larger patient populations with TAVR.

6. Conclusions

This meta-analysis showed that atrial fibrillation is associated with a higher risk of all primary and secondary outcomes. Specifically, NOAF but not pre-AF is associated with a higher risk of 30-day mortality, stroke, and extended LOS in patients with TAVR/TAVI. Future studies are needed to comprehensively analyze the anatomic and metabolic pathways that trigger the onset of NOAF and its potentially fatal sequelae in patients undergoing TAVR/TAVI. Obtained findings may be useful in developing novel strategies for minimizing the incidence of 30-day mortality, early bleeding, stroke, AKI, and extended LOS in patients with TAVI/TAVR.

7. Protocol Registration

None.

Funding

The study was not supported by any funding sources

Author contributions

NN conceived the study hypothesis. NN, HA, KE, RB and AI designed the study and performed the systematic search, study selection, and data extraction. NN analyzed the data. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the data, writing and critical editing of the manuscript.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Mahmaljy H., Tawney A., Young M. StatPearls Publishing; Treasure Island, FL: 2021. Transcatheter aortic valve replacement. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ielasi A., Latib A., Tespili M., Donatelli F. Current results and remaining challenges of trans-catheter aortic valve replacement expansion in intermediate and low risk patients. Int. J. Cardiol. Heart Vasc. 2019;23:100375. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcha.2019.100375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Terré J.A., George I., Smith C.R. Pros and cons of transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) Ann. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2017;6(5):444–452. doi: 10.21037/acs.2017.09.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fukui M., Gupta A., Abdelkarim I., Sharbaugh M.S., Althouse A.D., Elzomor H., Mulukutla S., Lee J.S., Schindler J.T., Gleason T.G., Cavalcante J.L. Association of Structural and Functional Cardiac Changes With Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement Outcomes in Patients With Aortic Stenosis. JAMA Cardiol. 2019;4(3):215. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2018.4830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shaul A.A., Kornowski R., Bental T., Vaknin-Assa H., Assali A., Golovchiner G., Kadmon E., Codner P., Orvin K., Strasberg B., Barsheshet A. Type of atrial fibrillation and clinical outcomes in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement. Ann. Noninvasive. Electrocardiol. 2016;21(5):519–525. doi: 10.1111/anec.12345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robert R., Porot G., Vernay C., Buffet P., Fichot M., Guenancia C., Pommier T., Mouhat B., Cottin Y., Lorgis L. Incidence, predictive factors, and prognostic impact of silent atrial fibrillation after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Am. J. Cardiol. 2018;122(3):446–454. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2018.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Angsubhakorn N., Kittipibul V., Prasitlumkum N., Kewcharoen J., Cheungpasitporn W., Ungprasert P. Non-transfemoral transcatheter aortic valve replacement approach is associated with a higher risk of new-onset atrial fibrillation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart Lung Circ. 2020;29(5):748–758. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2019.06.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kheiri B., Osman M., Bakhit A., Radaideh Q., Barbarawi M., Zayed Y., Golwala H., Zahr F., Stone G.W., Bhatt D.L. Meta-analysis of transcatheter aortic valve replacement in low-risk patients. Am. J. Med. 2020;133(2):e38–e41. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2019.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Selcuk A.A. A guide for systematic reviews: PRISMA. Turk Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2019;57(1):57–58. doi: 10.5152/tao.2019.4058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kang E.Y., Park Y., Li X., Segrè A.V., Han B., Eskin E. ForestPMPlot: A flexible tool for visualizing heterogeneity between studies in meta-analysis. G3 (Bethesda) 2016;6:1793–1798. doi: 10.1534/g3.116.029439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hippel P.T.V. The heterogeneity statistic I2 can be biased in small meta-analyses. BMC Med. Res. Method. 2015;15:1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12874-015-0024-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Godavitarne C., Robertson A., Ricketts D.M., Rogers B.A. Understanding and interpreting funnel plots for the clinician. Br. J. Hosp. Med. 2018;79(10):578–583. doi: 10.12968/hmed.2018.79.10.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ludbrook J. Should we use one-sided or two-sided P values in tests of significance? Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2013;40(6):357–361. doi: 10.1111/1440-1681.12086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holland D., Wang Y., Thompson W.K., Schork A., Chen C.-H., Lo M.-T., Witoelar A., Werge T., O'Donovan M., Andreassen O.A., Dale A.M. Estimating effect sizes and expected replication probabilities from GWAS summary statistics. Front. Genet. 2016;7 doi: 10.3389/fgene.2016.00015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Amat-Santos I.J., Rodés-Cabau J., Urena M., DeLarochellière R., Doyle D., Bagur R., Villeneuve J., Côté M., Nombela-Franco L., Philippon F., Pibarot P., Dumont E. Incidence, predictive factors, and prognostic value of new-onset atrial fibrillation following transcatheter aortic valve implantation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2012;59(2):178–188. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.09.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Biviano A.B., Nazif T., Dizon J., Garan H., Fleitman J., Hassan D., Kapadia S., Babaliaros V., Xu K.e., Parvataneni R., Rodes-Cabau J., Szeto W.Y., Fearon W.F., Dvir D., Dewey T., Williams M., Mack M.J., Webb J.G., Miller D.C., Smith C.R., Leon M.B., Kodali S. Atrial fibrillation Is associated with increased mortality in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement: Insights from the PARTNER trial. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2016;9(1) doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.115.002766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chopard R., Teiger E., Meneveau N., Chocron S., Gilard M., Laskar M., Eltchaninoff H., Iung B., Leprince P., Chevreul K., Prat A., Lievre M., Leguerrier A., Donzeau-Gouge P., Fajadet J., Mouillet G., Schiele F. Baseline characteristics and prognostic implications of pre-existing and new-onset atrial fibrillation after transcatheter aortic valve implantation: Results from the FRANCE-2 registry. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8(10):1346–1355. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2015.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sannino A., Stoler R.C., Lima B., Szerlip M., Henry A.C., Vallabhan R., Kowal R.C., Brown D.L., Mack M.J., Grayburn P.A. Frequency of and prognostic significance of atrial fibrillation in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Am. J. Cardiol. 2016;118(10):1527–1532. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2016.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stortecky S., Buellesfeld L., Wenaweser P., Heg D., Pilgrim T., Khattab A.A., Gloekler S., Huber C., Nietlispach F., Meier B., Jüni P., Windecker S. Atrial fibrillation and aortic stenosis: Impact on clinical outcomes among patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2013;6(1):77–84. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.112.000124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tarantini G., Mojoli M., Windecker S., et al. Prevalence and impact of atrial fibrillation in patients with severe aortic stenosis undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement: an analysis from the SOURCE XT prospective multicenter registry. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;9:937–946. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2016.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yankelson L., Steinvil A., Gershovitz L., Leshem-Rubinow E., Furer A., Viskin S., Keren G., Banai S., Finkelstein A. Atrial fibrillation, stroke, and mortality rates after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Am. J. Cardiol. 2014;114(12):1861–1866. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nombela-Franco L., Webb J.G., de Jaegere P.P., Toggweiler S., Nuis R.-J., Dager A.E., Amat-Santos I.J., Cheung A., Ye J., Binder R.K., van der Boon R.M., Van Mieghem N., Benitez L.M., Pérez S., Lopez J., San Roman J.A., Doyle D., DeLarochellière R., Urena M., Leipsic J., Dumont E., Rodés-Cabau J. Timing, predictive factors, and prognostic value of cerebrovascular events in a large cohort of patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Circulation. 2012;126(25):3041–3053. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.110981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mentias A., Saad M., Girotra S., et al. Impact of pre-existing and new-onset atrial fibrillation on outcomes after transcatheter aortic valve replacement. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2020;12:2119–2129. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2019.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maan A., Heist E.K., Passeri J., Inglessis I., Baker J., Ptaszek L., Vlahakes G., Ruskin J.N., Palacios I., Sundt T., Mansour M. Impact of atrial fibrillation on outcomes in patients who underwent transcatheter aortic valve replacement. Am. J. Cardiol. 2015;115(2):220–226. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yoon Y.-H., Ahn J.-M., Kang D.-Y., Ko E., Lee P.H., Lee S.-W., Kim H.J., Kim J.B., Choo S.J., Park D.-W., Park S.-J. Incidence, Predictors, Management, and Clinical Significance of New-Onset Atrial Fibrillation After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation. Am. J. Cardiol. 2019;123(7):1127–1133. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2018.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patil N., Strassle P.D., Arora S., Patel C., Gangani K., Vavalle J.P. Trends and effect of atrial fibrillation on inpatient outcomes after transcatheter aortic valve replacement. Cardiovasc. Diagn. Ther. 2020;10(1):3–11. doi: 10.21037/cdt.2019.05.05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zweiker D., Fröschl M., Tiede S., Weidinger P., Schmid J., Manninger M., Brussee H., Zweiker R., Binder J., Mächler H., Marte W., Maier R., Luha O., Schmidt A., Scherr D. Atrial fibrillation in transcatheter aortic valve implantation patients: Incidence, outcome and predictors of new onset. J. Electrocardiol. 2017;50(4):402–409. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2017.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barbash I.M., Minha Sa'ar, Ben-Dor I., Dvir D., Torguson R., Aly M., Bond E., Satler L.F., Pichard A.D., Waksman R. Predictors and clinical implications of atrial fibrillation in patients with severe aortic stenosis undergoing transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Catheter. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2015;85(3):468–477. doi: 10.1002/ccd.25708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Okuno T., Hagemeyer D., Brugger N., et al. Valvular and nonvalvular atrial fibrillation in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2020;13:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2020.05.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mojoli M., Gersh B.J., Barioli A., Masiero G., Tellaroli P., D'Amico G., Tarantini G. Impact of atrial fibrillation on outcomes of patients treated by transcatheter aortic valve implantation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. Heart J. 2017;192:64–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2017.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Siontis G.C.M., Praz F., Lanz J., Vollenbroich R., Roten L., Stortecky S., Räber L., Windecker S., Pilgrim T. New-onset arrhythmias following transcatheter aortic valve implantation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart. 2018;104(14):1208–1215. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2017-312310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sannino A., Gargiulo G., Schiattarella G.G., Perrino C., Stabile E., Losi M.-A., Galderisi M., Izzo R., de Simone G., Trimarco B., Esposito G. A meta-analysis of the impact of pre-existing and new-onset atrial fibrillation on clinical outcomes in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve implantation. EuroIntervention. 2016;12(8):e1047–e1056. doi: 10.4244/EIJY15M11_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matsuo K., Fujita A., Tanaka J., Nakai T., Kohta M., Hosoda K., Shinke T., Hirata K.-I., Kohmura E. Successful cerebral thrombectomy for a nonagenarian with stroke in the subacute phase after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Surg. Neurol. Int. 2017;8(1):193. doi: 10.4103/sni.sni_208_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jørgensen T.H., Thyregod H.G.H., Tarp J.B., Svendsen J.H., Søndergaard L. Temporal changes of new-onset atrial fibrillation in patients randomized. Int. J. Cardiol. 2017;234:16–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.02.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Davlouros P.A., Mplani V.C., Koniari I., Tsigkas G., Hahalis G. Transcatheter aortic valve replacement and stroke: a comprehensive review. J. Geriatr. Cardiol. 2018;15:95–104. doi: 10.11909/j.issn.1671-5411.2018.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Depboylu B.C., Yazman S., Harmandar B. Complications of transcatheter aortic valve replacement and rescue attempts. Vessel. Plus. 2018;2(9):26. doi: 10.20517/2574-1209.2018.39. [DOI] [Google Scholar]