Abstract

Background

Expanding technologies of early detection of Alzheimer’s disease allow to identify individuals at risk of dementia in early and asymptomatic disease stages. Neuropsychiatric symptoms, such as anxiety and depression, are common in the course of AD and may be clinically observed many years before the onset of significant cognitive symptoms. To date, therapeutic interventions for AD focus on pharmacological and life style modification-based strategies. However, despite good evidence for psychotherapy in late-life depression, evidence for such therapeutic approaches to improve cognitive and emotional well-being and thereby reduce psychological risk factors in the course of AD are sparse.

Methods

A systematic review was conducted in PUBMED, PsycINFO, Web of Science, and Clinical Trials to summarize the state of evidence on psychotherapeutic and psychoeducational interventions for individuals at risk for Alzheimer’s dementia. Eligible articles needed to apply a manualized and standardized psychotherapeutic or psychoeducational content administered by trained professionals for individuals with subjective cognitive decline or mild cognitive impairment and measure mental health, quality of life or well-being.

Results

The literature search yielded 32 studies that were included in this narrative summary. The data illustrates heterogeneous therapeutic approaches with mostly small sample sizes and short follow-up monitoring. Strength of evidence from randomized-controlled studies for interventions that may improve mood and well-being is scarce. Qualitative data suggests positive impact on cognitive restructuring, and disease acceptance, including positive effects on quality of life. Specific therapeutic determinants of efficacy have not been identified to date.

Conclusions

This review underlines the need of specific psychotherapeutic and psychoeducational approaches for individuals at risk of Alzheimer’s dementia, particularly in terms of an early intervention aiming at improving mental health and well-being. One challenge is the modification of psychotherapeutic techniques according to the different stages of cognitive decline in the course of AD, which is needed to be sensitive to the individual needs.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13195-021-00956-8.

Keywords: Psychotherapy, Psychoeducation, Prevention, Individuals at risk, Subjective cognitive decline, Mild cognitive impairment, Alzheimer’s disease, Alzheimer’s dementia

Background

Neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD) have become a major public health challenge. It is estimated that due to the rapidly aging population, the dementia prevalence will rise up to 135.5 million patients in 2050 [1]. Expanding technologies of early disease detection allow biomarker-based diagnosis in the preclinical and prodromal stages, long before functional disability of dementia becomes apparent [2–4]. The preclinical phase of AD comprises the condition of subjective cognitive decline (SCD), where healthy adults are concerned about a cognitive decline, while performance on neuropsychological testing is within normal limits and activities of daily living (ADL) are preserved [3]. Individuals with SCD with a biomarker-based evidence of AD are at higher risk for developing cognitive decline [5–7]. The prodromal phase of AD is the condition of mild cognitive impairment (MCI), which is an at risk state for Alzheimer’s dementia and is defined as a clinical condition, where subjects have mild cognitive decline, but preserved ADL [2], thus not fulfilling dementia criteria. Individuals diagnosed with MCI are a heterogeneous group, with only about 30 % of them developing Alzheimer’s dementia within 3 years after clinical MCI diagnosis [8]. However, MCI patients with a biomarker-based evidence of AD have a high risk of approximately 70% to develop Alzheimer’s dementia within 3 years [9]. Currently, research on early disease identification, dementia risk-prediction, and prevention strategies in pre-dementia stages of AD is carried out with the aim of impacting on modifiable risk factors and targeting molecular pathways of AD to ultimately slow the disease course [10–13]. As epidemiological studies suggest, about one third of dementia cases worldwide can be attributed to potentially modifiable risk factors [14]. Against this background, non-pharmacological prevention strategies are investigated more intensely. Several prevention studies with a multidimensional approach (including physical, lifestyle, cognitive and nutritional interventions) aim to reduce modifying risk factors for AD targeting the primary outcome to improve the cognitive outcome, but essentially leaving behind psychological risk factors for AD [13, 15–21]. Psychological risk factors include neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS), including anxiety, depression, and sleep disturbance. NPS may accelerate the course of neurodegenerative diseases and are potential modifying risk factors for cognitive decline [21–25]. There seems to be a bi-directional relationship between (sub-) syndromal NPS and cognitive decline. While NPS may enhance cognitive decline and may also be the early manifestation of a pre-dementia-stage of a neurodegenerative disorder, such as AD, cognitive decline in itself may stimulate NPS, particularly due to the psychological burden associated with worsening of cognition. Several studies highlight the profound stress, anxiety, and worries that individuals and close-others encounter shortly after early AD detection [26–28]. For individuals at risk of developing Alzheimer’s dementia, the diagnosis of MCI may increase their uncertainty, as it is associated with an unclear prognosis on the level of an individual. We know from literature that individuals with MCI encounter difficulties in social, psychological, and daily living context, which may lead to depression or anxiety and they specifically ask for information about the causes of the syndrome, the potential disease course, accompanying symptoms, social consequences, and available treatments [26]. However, little is known on how individuals in at risk stages for Alzheimer’s dementia cope with their diagnosis and their impending impairments in the long-term. In the face of an, to a certain degree, unpredictable and still incurable disease like AD, disease acceptance and its consequences are of paramount importance for the patient and their close-others. There is empirical evidence that coping strategies and illness perceptions have a major impact on well-being and quality of life of individuals with chronic diseases [29]. The field of psychooncology has been integrated to the management of cancer patients since the early 1970s. Psychooncology contributes to the clinical care of patients, to the training of personnel in psychological management of cancer patients, to cancer prevention strategies and to the management of psychiatric and psychosocial problems during the continuum of the cancer illness. There is empirical evidence that psychosocial care in oncology helps to alleviate emotional burden and improves well-being in patients and close-others. The psychooncological care follows a stepped approach with a special focus on the individual patients’ needs during the disease course, from the disease prevention, to diagnosis, to therapy and follow-up care. This model could provide the framework for a holistic disease management for patients and their close- others in the continuum of AD, from the early preclinical stage, such as SCD, to the dementia stage, with adapted contents. At the current stage, a comprehensive psychotherapeutic concept with the scope of prevention, self-management, and coping, as well as improving well-being, mental health, and quality of life within the course of Alzheimer’s disease is still lacking.

Non-pharmacological interventions that focus on cognitive function such as the impact of cognitive function on daily living have been widely studied in individuals with MCI. The majority is investigating effects of cognitive training interventions such as cognitive remediation or compensation approaches and moreover physical exercise interventions [30, 31]. There is some evidence that cognitive training and physical interventions may improve cognitive abilities in individuals with MCI; however, the effects on daily functioning are small. There is some ongoing research on non-pharmacological interventions for individuals with SCD, which strengthen the impact of cognitive and psychological interventions to improve mental health such as cognitive and emotional well-being [32, 33].

In summary, data on psychotherapeutic interventions and their effects on mental health and quality of life in early disease stages of AD is sparse. Therefore, the aim of this systematic review is to provide an overview on current concepts for psychotherapeutic and psychoeducational interventions for individuals in early disease stages of AD, such as individuals with SCD and MCI, and their effects on behavioral or psychological outcomes, such as depression, anxiety, or quality of life.

Methods

Search strategy

Search strings consisted of three sections that were combined using the Boolean Operator “AND.” One section was referring to the psychotherapy and psychoeducational intervention, the second section was referring to the at risk stages of Alzheimer’s disease “mild cognitive impairment” and “subjective cognitive impairment,” and the third section was referring to Alzheimer’s disease (see Additional file 1 for the detailed search strings). The final search from inception to June 2021 (last read out 09.06.2021) was carried out in PUBMED, PsycINFO, Web of Science, and Clinical Trials. Furthermore, the reference lists of all publications included in this review were hand searched for additional studies. Search strategy, screening, and data selection were carried out in accordance with the PRISMA criteria [34]. This review is registered in the international prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO) with the registration number: CRD42020145399.

Paper selection/inclusion criteria

We included studies that investigated individuals at risk of developing Alzheimer’s dementia, such as individuals with SCD or MCI. The diagnosis of MCI needed to be defined according to the NIA-AA criteria for mild cognitive impairment or according to the MCI criteria of Petersen 2004 [2, 35]. Since the stage of late MCI and early dementia is often a transition stage, studies that investigated this particular patient group were also included, when they were considered relevant for our research question. Therefore, a number of included studies refer to the transitional stage of late MCI and mild dementia [36–39]. Due to the recent standardization of SCD [40], we decided to broaden the definition of SCD to conceptually equivalent diagnosis, to include as many studies as possible in this review. We used the Jessen et al. [40] criteria to decide, whether the study populations met the criteria for SCD, when authors did not specify the underlying SCD concept. Inclusion criteria were that articles were published in a peer-reviewed journal in English or German language. No restriction regarding the publication date was applied. This review considered all types of study designs including quantitative (such as observational, prospective and retrospective cohort studies, clinical trials, randomized-controlled trial (RCT)), qualitative, and mixed methods designs. To be included, studies had to apply a manualized and standardized psychotherapeutic or psychoeducational content administered by specifically trained professionals and had to measure mood or quality of life as a primary or secondary outcome. The interventions needed to be clearly described.

Screening and assessment of studies

In the screening process, eligibility based on title and abstract was checked according to the inclusion criteria. These procedures were performed by two independent reviewers. Discrepancies in rating were resolved through discussion, and when necessary, a third reviewer judged the respective publication. In case of an unclear eligibility, a full text review was performed.

Data extraction

Due to the heterogeneity of study results with regard to intervention type, study length, measuring methods, and outcome measures, we decided to perform a systematic narrative review. In order to ensure a systematic data extraction for the narrative review, an evaluation matrix for data analyses was designed based on the inclusion criteria and our research question. Two independent reviewers performed data analyses and, in case of any discrepancies, a third reviewer re-evaluated. The next steps included extraction of additional information on study design, characteristics, and population and on the main outcome measures. The narrative synthesis included the target population characteristics, the therapeutic interventions, the methodology, the study setting, and the type of outcome. Thematic categories were predefined based on the research question and were further refined during the data analysis process.

Quality assessment (risk of bias)

The quality of included studies was evaluated by two independent reviewers using the risk of bias tool proposed by Hawker et al. in 2002 (see Table 1) [41]. The tool comprises 9 items (summed score from 10 = very poor to 40 = good) relating to abstract and title, introduction and aims, method and data, sampling, data analysis, ethics and bias, presentation of results, transferability, and usefulness in order to judge the methodological rigor of the studies. Discrepancies between raters were resolved by discussion and where necessary re-assessed by a third reviewer.

Table 1.

Study characteristics

| Study and country | Sample size (N) | Follow-up | Characteristics | Intervention | Control | Study design | Outcomes | Main findings | Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychotherapy for individuals with MCI | |||||||||

|

Gildengers et al. 2016 USA |

94 | 3/6/9/12 m post-int. |

Patients: N = 74 Dg.: MCI Gender: 47 f, 27 m Age: 75 yrs. (M) MMSE: / Caregivers: N = 20 Gender: 16 f, 4 m Age: 66.6 yrs. (M) |

Problem-solving therapy (PST) with and without moderate-intensity physical exercise (PE) | Usual care enhanced by the same assessments as the intervention group |

Single-blinded randomized controlled trial. Couples therapy led by master’s level therapists |

− Depression (Prime-MD/Mini) − Anxiety (GAD-7) |

Preliminary results: high acceptance for intervention and usefulness in managing stress and cognitive problems | Good |

|

Joosten-Weyn Banningh et al. 2008 Netherlands |

46 | 2w post-int. |

Patients: N = 23 Dg: MCI Gender: 13f, 10 m Age: 68.7 yrs. (M) MMSE 26.7 (M) Caregivers: N = 23 Gender: 12f, 11 m Age: 70.4 yrs. (M) |

Combination of cognitive behavioral therapy and psychoeducation | N/A |

Non-randomized trial Group therapy led by psychotherapists |

− Depression (GDS) − Well-being (SF-36) − Subscales Acceptance and Helplessness (ICQ) − Marital satisfaction (MMQ) − Burden of Caregiver |

Preliminary results: high motivation for intervention. Evidence for significant increase of acceptance and a trend for an increased marital satisfaction. The significant others reported an increased awareness of memory and behavioral problems | Good |

|

Joosten-Weyn Banningh et al. 2011, 2013 Netherlands |

94 | 6–8 m post-int. |

Patients: N = 47 Dg.: MCI Gender: 20 f, 27 m Age: 69.9 yrs. (M) MMSE: 25.7 (M) Caregivers: N = 47 Gender: 31f, 16 m Age: 68.5 yrs. (M) |

Combination of cognitive behavioral therapy and psychoeducation | Waiting-list |

Non-randomized trial Group therapy led by psychotherapists |

− Depression (GDS) − Well-being (SF-36) − Subscales Acceptance and Helplessness (ICQ) − Marital satisfaction (MMQ) − Burden of Caregiver |

Increase of acceptance in MCI patients was maintained at follow-up, with increased insight into cognitive decline. Increase in sense of competence increased in the significant others. Worse helplessness and well-being at follow-up compared to post-intervention in patients and significant others | Good |

|

Miller et al. 2007 USA |

1 | N/A |

Dg.: MCI Gender: 1 m Age: 80 yrs. MMSE: / |

Interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) for depressed elders | N/A | Individual therapy led by psychiatrists. | − Depression | Standard IPT techniques need to be modified, including active integration of the caregiver into the treatment process | Fair |

|

Scheurich et al. 2008 Germany |

24 | 12 m post-int. |

Patients: N = 12, Dg.: MCI Gender: 7f, 5 m Age: 66.8 yrs. (M) MMST: 24 (M) Caregivers N = 12, Gender: 7f, 5 m Age: 61.5 yrs. (M) |

Combination of cognitive behavioral therapy and psychoeducation | N/A |

Non-randomized pilot trial Group therapy, no information about the professional background of therapist |

− Depression (GDS, BDI) − Life quality (SF-36) |

Reduced anxiety, anergia, and withdrawal in MCI patients. Caregivers showed reduced sleep disturbances, irritability, and aggressiveness toward the diseased family member | Good |

|

Tonga et al. 2016 Norway |

3 | N/A |

Patients: N = 3 Dg.: mild AD Gender: 2f, 1 m Age: 59 yrs., 66 yrs., 77 yrs. MMSE: 27, 23, 20 |

Cognitive Rehabilitation and Cognitive behavioral therapy (Cordial Manual) [72] | N/A | Individual therapy led by a psychologist |

− Depression (HADS) − Anxiety (HADS) − Client Satisfaction (CSQ-8) − Burden of Caregiver (RSS) |

Apathy and anosognosia hindered treatment adherence, while caregivers were essential for treatment and homework completion. Psychotherapy for individuals with AD needs to allow flexibility of the manual, according to the resources and preferences of the patients | Fair |

|

Tonga et al. 2021 Norway |

198 | 4/10 m post-baseline |

Intervention group: N = 100 Dg.: MCI (n = 32) and dementia (n = 68) Gender: 45f, 55 m Age: 69.4 (M) MMSE: 24.7 (M) Caregivers: N = 100 Gender: 66f, 34 m Age: 66.8 yrs. (M) Control group: N = 98 Dg.: MCI (n = 48), dementia (n = 48) Gender: 47f, 51 m Age: 70.7 yrs. (M) MMSE: 24.5 (M) Caregivers: N = 98 Gender: 67f, 31 m Age: 65.7 yrs. (M) |

Cognitive Rehabilitation and Cognitive-behavioral therapy (Cordial Manual) [72] | Treatment as usual |

Randomized controlled trial Group therapy led by nurses, psychiatrists, occupational therapists and psychologists |

− Depression (MADRS) − Neuropsychiatric Inventory − Quality of life (QoL-AD) |

Significant improvement in depression within the intervention group compared to the control group. No group differences with regard to neuropsychiatric symptoms or quality of life | Good |

| Psychoeducational intervention for Individuals with MCI | |||||||||

|

Barton et al. 2017 UK |

16 | 8w post-int. |

Patients: N = 16 Dg.: MCI Gender: 9f, 7 m Age: 74.2 yrs. (M) MMSE: / |

Psychosocial group intervention based on the recovery model and psychoeducation | N/A |

Non-randomized trial Group therapy led by facilitators trained in group therapy |

− Mental Well-Being (Warwick Edinburgh Scale) − Goal Attainment Scale |

Well-being improved significantly and satisfaction with the intervention was high | Fair |

|

Bier et al. 2015 (study protocol) Belleville et al. 2018 Canada |

145 | 3/6 m post-int. |

Psychosocial intervention group: N = 43, Dg.: MCI Gender: 24f, 19 m Age: 72.1 yrs. (M) MMSE: / Cognitive intervention group: N = 40 Dg.: MCI Gender: 20f, 20 m Age: 71.3 yrs. (M) MMSE: / Control group: N = 44, Dg.: MCI Gender:26f, 18 m Age: 73.1 yrs. (M) MMSE: / |

Cognitive intervention according to the MEMO program (MEMO-program) [59] Psychosocial intervention with a CBT approach and psychoeducation |

No contact group (no intervention) |

Single-blinded randomized controlled trial Group therapy led by therapists (qualified clinicians) |

− Depression (GDS) − Anxiety (GAI) − General well-being (GWBS) |

No significant effect on mood or well-being in neither group | Good |

|

Diamond et al. 2015 Australia |

64 | 2w post-int. |

Intervention group: N = 36, Dg.: MCI and/or MDD Gender: 27f, 9 m Age: 67.3 yrs. (M), MMSE: / Control group: N = 28, Dg.: MCI and/or MDD Gender: 16f, 12 m Age: 65.6 yrs. (M) MMSE: 28.5 (M) |

Multifaceted Healthy Brain Ageing Cognitive Training (HBA-CT) with psychoeducation and computerized cognitive training | Treatment as usual |

Single-blinded randomized controlled trial Group intervention led by multidisciplinary specialists (psychiatrists, neurologists, neuropsychologists, clinical psychologists) |

− Depression (GDS) − Subjective memory (EMQ) − Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) |

Improvements in self-reported memory, mood, and sleep in the intervention group | Good |

|

Kurz et al. 2009 Germany |

40 | N/A |

Intervention group: Dg.: MCI N = 18 Gender: 11f, 7 m Age: 70.4 yrs. (M) MMSE: 27,8 (M) Dg.: mild AD N = 10 Age: 66 yrs. 8 M) Gender: 5f, 5 m MMSE: 23.9 (M) Control group: Dg.: MCI N = 12 Dg.: MCI Gender: 6f, 6 m Age: 70.8 yrs. (M) MMSE: 28.0 (M) |

Cognitive rehabilitation program | Waiting list |

Non-randomized trial Group therapy, no information about the professional background of therapist |

− Depression (BDI) − Cognition (MMSE) − Activities of daily living (ADL) |

Significant improvements on mood and ADL in individuals with MCI | Good |

|

Larouche et al. 2019 Chouinard et al. 2019 Canada |

48 | 3 m post-int. |

Intervention group: N = 23; Dg.: MCI Gender: 9f, 14 m Age: 71.4 yrs. (M) MMSE: / Control group N = 22; Dg: aMCI Gender: 10f, 12 m Age: 70.5 yrs. (M) MMSE: / |

Mindfulness-based intervention (MBI) | Psychoeducation-based intervention (PBI) |

Single-blinded randomized controlled pilot trial Group intervention led by trained psychologists |

− Depression (GDS) − Anxiety (GAI) − Life quality (WHOQOL-Brief and WHOQOL-Brief OLD) |

Both interventions had positive effects on anxiety, depression, and age-related QoL | Good |

|

Lu et al. 2013 USA |

20 | 3 m post-int. |

Patients: N = 10 Dg: MCI Gender: 3f, 7 m Age: 69.2 yrs. (M) MMSE: 27.1 (M) Caregivers: N = 10 Gender: 7f, 3 m Age: 66 yrs. (M) |

Daily Enhancement of Meaningful Activity (DEMA) intervention with components of problem-solving therapy (PST) | N/A |

Non-randomized pilot trial Individual and Couples therapy led by trained nurses |

− Depression (PHQ-9) − Well-being (SF-36) − Quality of life (QoL-AD) − Caregiver Burden Scale (CBS) |

Evidence for acceptance and feasibility for the program. No significant effects on depression, quality of life and caregiver burden | Good |

|

Lu et al. 2016 Ellis et al. 2019 USA |

72 | 3 m post-int. |

Intervention group Patients: N = 17 Dg.: MCI Gender: / Age: 71.6 yrs. (M) MMSE: / Caregivers: N = 17 Gender: / Age: 65.5 yrs. (M) Control group: Patients: N = 19 Dg: MCI Gender: / Age: 76.8 yrs. (M) MMSE: / Caregivers: N = 19 Gender: / Age: 70.8 yrs. (M) |

Daily Enhancement of Meaningful Activity (DEMA) intervention with components of problem-solving therapy (PST) | Information support attention control group |

Randomized controlled pilot trial Individual and couples therapy led by trained nurses |

− Depression (PHQ-9) | No significant effect on mood in neither group. The intervention group indicated significantly higher usefulness, ease of use, and total satisfaction than the control group. No significant group difference in the caregivers’ ratings regarding satisfaction with the treatment | Good |

|

Rovner et al. 2012, 2016, 2018 USA |

221 | 6/12/18/24 m post-int. |

Intervention group: N = 111 Dg: MCI Gender: 86 f, 25 m Age: 75.5 yrs. (M) MMSE: 25.8 (M) Control group: N = 110 Dg: MCI Gender: 89 f, 21 m Age: 76.2 yrs. (M) MMSE: 25.6 (M) |

Behavioral activation therapy: a manual-based behavioral treatment to increase cognitive, physical and/or social activity | Supportive therapy offered a structured, nondirective psychological treatment |

Single-blinded randomized controlled trial Individual intervention led by trained community health workers |

− Depression (GDS) − Quality of life |

No significant group difference on depression in both treatment groups | Good |

|

Schmitter-Edgecombe et al. 2014 USA |

46 | 3 m post-int. |

Intervention group: N = 23 care-dyads Patients: Dg.: MCI Gender: 16f, 7 m Age: 72.96 yrs. (M) MMSE: / Control group: N = 23 care-dyads Patients: Dg: MCI Gender: 11f, 12 m Age: 73.35 yrs. (M) MMSE: / |

Cognitive rehabilitation multi-family group intervention, including problem-solving therapy and psychoeducation | Standard care |

Randomized controlled trial Group intervention led by trained clinical psychology doctoral students and community professionals (i.e., psychologists, social workers) |

− Quality of Life-Alzheimer’s disease (QOL-AD) − Depression (GDS) − Coping (CSE) |

No significant group differences on psychological measures. Caregivers reported improved coping behavior | Good |

|

Smith et al. 2017 (study protocol) Chandler et al. 2019 USA |

272 | 6/12/18 m post-int. |

Patients: N = 272 Dg.: MCI Gender: 112f, 160 m Age: 75 yrs. (M), MMSE: 28.36 (M) |

Mayo Clinic Healthy Action to Benefit Independence and Thinking (HABIT) program, a 50-h group intervention including psychoeducation, memory compensation training, computerized cognitive training, yoga, patient and partner support groups, and wellness education | N/A |

Multisite, cluster randomized trial Group intervention led by therapist (neuropsychologists, dementia educators, exercise specialists, nurse practitioners, social workers) |

− Quality of Life-Alzheimer’s disease (QOL-AD) − Depression (CES-D) − Modified chronic disease Self-Efficacy Scale |

No significant effects on the outcomes could be determined in neither intervention group by 12 months. Wellness education had a greater effect on mood than computerized cognitive training, and yoga had a greater effect on activities of daily living than support groups at 12 months. Cognitive training had the least effect on these outcomes | Good |

|

Wells et al. 2013, 2019 USA |

14 | 2 m post-baseline |

Intervention group: N = 9 Dg: MCI Gender: / Age: 73 yrs. (M) MMSE: 27 (M) Control group: N = 5, Dg: MCI Gender: / Age: 75 yrs. (M), MMSE: 27 (M) |

Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR), standardized mindfulness meditation intervention, with psychoeducation on stress and stress relief | Waiting list |

Randomized controlled pilot trial Group intervention, no information about the professional background of therapist |

− Quality of Life-Alzheimer’s disease (QOL-AD) − Depression (CES-D) − Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) − Resilience Scale (RS) − Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS) |

No significant group differences with regard to psychological outcomes. The qualitative interviews revealed positive perceptions of class attendance, development of mindfulness skills, including meta-cognition, importance of the group experience, enhanced well-being, shift in MCI perspective, decreased stress reactivity and increased relaxation, improvement in interpersonal skills | Fair |

| Psychotherapy for Individuals with SCD | |||||||||

| N/A | |||||||||

| Psychoeducational intervention for Individuals with SCD | |||||||||

|

Cohen-Mansfield et al. 2015 Israel |

44 | 10 weeks post-baseline |

Health promotion: N = 15, Dg.: SCD Gender: 13f, 2 m Age: 74.44 yrs. (M), MMSE: 28.67 (M) Cognitive Training: N = 15, Dg.: SCD Gender: 9f, 6 m Age: 72.8 yrs. (M), MMSE: 27.93 (M) Participation-centered: N = 14, Dg.: SCD Gender: 10f, 5 m Age: 73.21 yrs. (M) MMSE: 28.93 (M) |

Health promotion course: psychoeducation on health behaviors and lifestyle modification; dementia and delirium; age-related cognitive decline and MCI, such as cognitive activities to keep the mind fit. Cognitive training course: the Advanced Cognitive Training for Independent and Vital Elderly (ACTIVE) with focus on memory, reasoning, and speed of processing Participation centered course: CBT-based delivery of memory, cognitive, and organizational strategies |

Waiting list |

Single-blinded randomized controlled pilot trial Group intervention, no information about the professional background of therapist |

− Well-being (UCLA Loneliness Scale) − Depression (GDS) |

All three interventions resulted in significant improvement in cognitive function as measured by the computerized cognitive assessment. Self-report of memory difficulties decreased significantly in the cognitive training group participants. All approaches seemed to decrease loneliness | Good |

|

Hoogenhout et al. 2012 Netherlands |

50 | 4w post-int. |

Intervention group: N = 24 Dg.: SCD Gender: 24f Age: 66.0 yrs. (M) MMSE: 29.24 (M) Control group: N = 26 Dg.: SCD Gender: 26f Age: 66.1 yrs. (M) MMSE: 29.11 (M) |

Psychoeducation about cognitive aging and contextual factors (negative age stereotypes, beliefs, health and lifestyle), focusing on skills and compensatory behavior | Waiting list |

Randomized controlled trial Group intervention, no information about the professional background of therapist |

− Maastricht Metacognition Inventory (MMI)ESQ − Psychological Well-being Quotient (PWQ) |

Participants in the experimental group reported less emotional reactions towards cognitive functioning than participants in the control condition. The intervention improved an important aspect of metacognition. No significant differences between the groups in psychological well-being | Good |

|

Marchant et al. 2018 (study protocol) Marchant et al. 2021 Multi-center (France, Germany, Spain, UK) |

147 | 2/6 m post-baseline. |

Intervention group: N = 73 Dg.: SCD Gender: 47f, 26 m Age: 72.1 yrs. (M) MMSE: 28.7 (M) Control group: N = 74 Dg.: SCD Gender: 48f, 26 m Age: 73.3 yrs. (M) MMSE: 28.9 (M) |

Mindfulness based approach for seniors [76] with psychoeducational components | Health self-management program to promote engagement in activities to improve health and well-being |

Multi-center, observer-blind randomized controlled trial Group interventions led by clinically trained facilitators (mindfulness-based teachers, clinical psychologist or equivalent degree) |

− Anxiety (STAI) − Depression (GDS) − Emotion regulation − Mindfulness (FFMQ) − Life quality (WHOQOL-Brief) − Well-being (Loneliness Scale) − Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) |

No significant group differences with regard to psychological outcomes. Both interventions showed a reduction in trait anxiety on follow-up | Good |

|

Smart et al. 2016 Smart and Segalowith 2017 Canada |

38 | 2w post-int. |

Patients: N = 15 Dg.: SCD Gender: 11f, 4 m Age: 69.6 yrs. (M) MMSE: 28 (M) Control: N = 23 Dg.: healthy control Gender: 9f, 14 m MMSE: 27.78 (M) |

Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) based on Kabat-Zinn, standardized mindfulness meditation intervention, with psychoeducation on stress and stress relief | Psychoeducation on cognitive aging |

Single-blinded randomized controlled pilot trial Group intervention, no information about the professional background of therapist |

− Depression (GDS) − Mindfulness (FFMQ) − Anxiety (AMAS) − Negative mood regulation (NMR) |

No significant group differences with regard to psychological outcomes. Both interventions improved psychological findings (reduction of cognitive complaint, reduction of anxiety and self-judgment of one’s own mental functioning) | Good |

AD Alzheimer’s disease; ADL Activities of Daily Living; AMAS Adult Manifest Anxiety Scale; BDI Beck Depression Inventory; CBS Caregiving Burden Scale; CES-D Center of Epidemiology Depression Scale; CSE Coping Self-efficacy scale; CSQ-8 Client Satisfaction Scale; Dg. diagnosis; f, female; FFMQ Five-Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire; FU follow-up; GAD-7 Generalized Anxiety Questionnaire; GAI Geriatric Anxiety Inventory; GDS Geriatric Depression Scale; GSE General Self-Efficacy Scale; GWBS General Well-Being Schedule; HADS Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; ICQ Illness Cognition Questionnaire; m male; M mean; MAAS Mindful Attention Awareness Scale; MADRS Montgomery–Asberg Depression Rating Scale; MBSR, mindfulness based stress reduction; MCI mild cognitive impairment; MDD major depressive disorder; Maudsley Marital Questionnaire; MMSE Mini Mental State Exam; MoCA Montreal Cognitive Assessment; MSEQ Memory Self-Efficacy Questionnaire; N, number; NMR Negative Mood Regulation Scale; PHQ Patient Health Questionnaire; post-int. post-intervention; PSQI Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; PSS Perceived Stress Scale; QoL Quality of Life; QOL-AD, Quality of Life in Alzheimer’s disease; RSS Relatives’ Stress Scale; SCD subjective cognitive decline; SF-36 Short Form Health 36; STAI State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; yrs years; w week; WHOQOL World Health Organization Quality of Life Brief scale

Results

Included studies

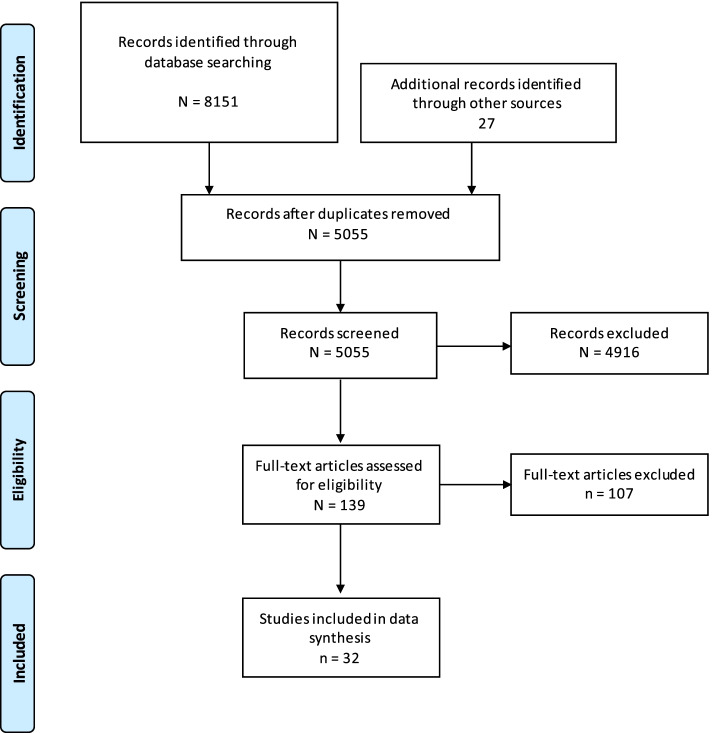

The initial search yielded 8151 papers. Twenty-six additional articles were identified through reference check. One hundred thirty-seven articles were selected for full text review. After full text review, 32 publications fulfilled the inclusion criteria for analysis. The detailed selection process according to the PRISMA criteria is depicted in Fig. 1 [34].

Fig. 1.

PRISMA Flow-Chart of database search

The 32 included papers are summarized in Table 1. Furthermore, some of the included publications referred to the same study and are marked as so in Table 1. Of the included papers, 13 originated from the USA [42–54], followed by 6 from Canada [55–60], 4 from the Netherlands [61–64], 2 from Germany [37, 38], 2 from Norway [36, 39], and one from each of the following countries: Australia [65], Israel [66], and UK [67]. Two publications referred to a multi-center study [68, 69], which was performed in France, Germany, Spain, and the UK. Among the 6 papers focusing on interventions for individuals with SCD, none explored the effects of a manualized psychotherapeutic intervention, but all offered psychoeducational interventions in addition to mindfulness-based stress reduction or health promotion and cognitive training courses. All were carried out within randomized controlled trials [55, 56, 61, 66, 68, 69]. A total of 26 papers referred to interventions with individuals with MCI. Amongst them, 8 papers described manualized psychotherapeutic interventions [36, 37, 39, 42, 43, 62–64] and 18 papers described psychoeducational interventions in addition to cognitive rehabilitation, cognitive training, mindfulness-based stress reduction, behavioral activation, or a recovery model approach [38, 44–54, 57–60, 65, 67]. The majority of studies included short-term (up to 12 weeks post intervention) or immediate post-intervention follow-up assessments. Long-term follow-up assessments (6 or more months post-intervention) were described in 14 publications [37, 39, 43, 48, 49, 51–53, 59, 60, 62, 63, 68, 69].

Systematic narrative review

Psychotherapy in individuals with MCI

A total of five research groups have described psychotherapeutic interventions in individuals with mild cognitive impairment [36, 37, 39, 42, 43, 62–64].

Three research groups have chosen a cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)-based approach and investigated the therapeutic effects in follow-up assessments, ranging from immediate post-intervention up to 12 months follow-up [36, 37, 39, 62–64]. With regard to therapeutic effects on mood in MCI patients, mixed findings were reported. Smaller non-randomized studies showed no significant effects, neither in the short-term (n = 94) [63] nor in the long-term follow-up (n = 24 [37], n = 94 [63]), whereas one recently published paper with a larger sample (n = 198) of a randomized-controlled study showed a significant reduction of depressive symptoms in the intervention group (cognitive rehabilitation and cognitive behavioral therapy) as compared to the treatment as usual control group by 6 months post-intervention (p < 0.001) [39]. The cognitive rehabilitation and cognitive behavioral treatment program comprised CBT, reminiscence therapy, and cognitive rehabilitation. This study, however, did not find any significant group changes with regard to overall neuropsychiatric symptoms or quality of life.

With regard to feelings of helplessness and well-being, Banningh et al. reported significantly worse findings on both scales 6–8 months post-intervention in all participants as compared to immediate post-interventional assessments (p < 0.05) [63]. Furthermore, disease acceptance in patients was maintained improved at 6-8 months follow-up (p < 0.001).

Preliminary and confirmatory findings from other studies reveal, that CBT-, problem-solving-therapy (PST)-, and interpersonal therapy (IPT)-based interventions are well accepted by and satisfying for participants, if the psychotherapeutic techniques are modified for the needs of the addressed population [37, 42, 43].

Psychoeducational interventions in individuals with MCI

A total of 10 research groups described psychoeducational interventions in addition to cognitive rehabilitation [38, 50], cognitive training [52, 53, 59, 60, 65], mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) [46, 47, 57, 58], behavioral activation [44, 45, 48, 49, 51, 54], or enriched by a recovery model approach [67], with follow-up assessments ranging from immediate post-intervention to 24 months follow-up.

With regard to mood, well-being and quality of life no therapeutic effects in MCI patients, neither at short-term (3 months) nor at long-term (24 months) follow-up, were detected in most studies, including four randomized controlled trials [48–51, 54, 59, 60] and one randomized non-controlled trial [52, 53]. The studies had mostly large samples and described psychoeducational interventions enriched with different approaches, ranging from cognitive rehabilitation (n = 46 [50] to behavioral activation (n = 72 [54], n = 221 [48, 49, 51]).

Cognitive training was applied by two research groups in addition to psychoeducation: the Canadian researchers used the MEMO program [70], which included episodic memory strategies as well as exercises to increase attentional control (n = 145 [59, 60]) and the US researchers followed the “Healthy Actions to Benefit Independence and Thinking” program with computer-based cognitive training (n = 272 [52, 53]).

Immediately post-interventional assessments in smaller randomized controlled (n = 64 [65]) and non-randomized waiting-list controlled (n = 40 [38]) studies, described significant improvements in depressive symptoms (p < 0.01 [38]; p = 0.01 [65]), subjective memory functioning (p = 0.03 [65]), and sleep quality (p = 0.01 [65]) in the intervention group as compared to a control group. Significant improvements in well-being 2 months after intervention as compared to baseline (p < 0.01) were reported by Barton et al. (n = 16) [67].

Qualitative data from one research group indicated a high acceptability and feasibility of a multi-component Daily Enhancement of Meaningful Activity (DEMA) intervention, including psychoeducation, planning of meaningful activities, dealing with negative emotions and coping strategies, with improvement in meaningful activities and satisfaction in the intervention group as compared to the control group at 3 months follow-up [44, 45].

Two research groups addressed the effects of psychoeducation-based interventions with MBSR-based therapy on MCI patients within randomized controlled trials (n = 48 (Chouinard et al. 2019; Larouche, Hudon, and Goulet 2019), n = 14 [46, 47]). The Canadian research group concluded that at 3 months follow-up, equivalent beneficial effects on depression (p = 0.03), anxiety (p = 0.02), and age-related quality of life (p = 0.02) were detected in both the intervention and control group [57, 58]. Furthermore, improved problem-focused coping strategies, particularly in active coping, were detected in both groups. The results were confirmed by research of Wells et al. [46, 47], where additional qualitative interviews with participants of the MBSR group revealed the development of mindfulness skills, benefits of the group experience, enhanced well-being, shift in MCI perspective, decreased stress reactivity, and increased relaxation and improvement in interpersonal skills.

Psychotherapy in individuals with SCD

Manualized psychotherapeutic interventions for individuals with SCD were not detected in the included studies.

Psychoeducational interventions in individuals with SCD

A total of four research groups described psychoeducational interventions alone [61] or in combination with cognitive training and CBT-based interventions [66] and MBSR-based interventions [55, 56, 68, 69] with follow-up ranging from immediately post-intervention to 6 months follow-up.

With regard to depression and well-being, significant therapeutic effects on individuals with SCD were neither reported by Cohen-Mansfield et al. (n = 44), describing three different intervention types (psychoeducational health promotion, cognitive training and a CBT-based participation-centered course), nor by Hoogenhout et al. (n = 50), following an exclusively psychoeducational approach. However, at 10 weeks follow-up, a trend on decreasing loneliness was detected in all three intervention groups, and self-reported memory difficulties were reduced significantly (p ≤ 0.05) in the study of Cohen-Mansfield et al. [66]. Hoogenhout et al. confirmed significant fewer negative emotional reactions toward cognitive functioning immediately post-intervention in the intervention group as compared to controls (p = 0.004) [61].

Two research groups investigated the effects of psychoeducation with MBSR-based therapy on individuals with SCD (n = 147 [68, 69], n = 38 [55, 56]). Marchant et al. conducted a multi-center randomized-controlled trial to investigate the impact of a MBSR intervention on psychological outcomes in comparison to a health self-management program in individuals with SCD. The authors concluded that no group differences were detected with regard to psychological outcomes at follow-up. However, both interventions showed a reduction in subclinical trait anxiety immediately post-intervention and at 6 months follow-up. The results were similar to a smaller study by Smart et al. [55, 56], where immediately post-intervention in both groups a trend in decrease in cognitive complaints, increase in memory self-efficacy, reduction in self-reported anxiety, and self-judgment of one’s own mental functioning was detected.

Conclusions

This systematic narrative review showed that studies on the effects of psychotherapeutic approaches for individuals at risk of Alzheimer’s dementia are limited. While reviews about this topic have been published before [32, 33, 71], we think this systematic review contributes insight to the current state of literature, as it (i) includes only trials that used standardized and manualized psychotherapeutic or psychoeducational interventions and (ii) covers the full spectrum of individuals at risk for Alzheimer’s dementia, including individuals with SCD and MCI.

This review comprises more studies on therapeutic interventions for MCI patients than for individuals with SCD. While a RCT with a large sample (n = 198) of MCI patients showed a significant reduction of depressive symptoms in the intervention group (cognitive rehabilitation and cognitive behavioral therapy) as compared to the treatment as usual control group 6 months post-intervention [39], non-randomized CBT-based trials with smaller sample sizes but longer follow-up assessments of 6–12 months did not find any effects on depressive symptoms (n = 24 [37], n = 94 [63]). Although psychoeducational interventional studies with small sample sizes detected some positive immediate post-interventional therapeutic effects on well-being (n = 16 [67]) and mood (n = 64 [65]; n = 40 [38]), this review underlines that the majority of existing evidence from randomized controlled (n = 145 (Belleville et al. 2018; Bier et al. 2015); n = 72 (Ellis, Altenburger, and Lu 2019); n = 221 (Rovner et al. 2012, 2018; Rovner and Casten 2016); n = 46 (Schmitter-Edgecombe and Dyck 2014)) and randomized non-controlled (n = 272 (Chandler et al. 2019; Smith et al. 2017)) trials with mostly large cohorts and longitudinal follow-ups, ranging from 3 to 24 months, does not confirm these findings.

With regard to psychotherapeutic interventions, no data in individuals with SCD were identified, while data regarding psychoeducational approaches addressing individuals with SCD are available from four research groups [55, 56, 61, 66, 68, 69]. The only study that was performed in a randomized controlled manner and in a large cohort of individuals with SCD revealed effects of both an MBSR-based intervention and a health self-management program, on mental health and quality of life at 6 months follow-up, but no group differences [69]. The study, however, showed a significant reduction of trait anxiety post-intervention in both groups, intervention and control, that was maintained at 6 months follow-up.

Literature indicates that individuals with cognitive impairment, such as MCI, need highly individualized psychotherapeutic interventions, as these impairments interfere with the ability to adopt new coping skills, problem-solving skills, and transfer acquired skills to everyday life [36, 72]. This review depicts that psychotherapeutic and psychoeducational interventions for older adults in pre-dementia stages are feasible and may suggest that the degree of cognitive impairment in the pre-dementia stages may not necessarily influence the ability to learn skills such as psychotherapeutic or mindfulness interventions [39, 42, 46, 47, 62, 63]. Informatively, the qualitative ratings of perceived benefit and understanding of the intervention were not correlated with baseline cognition, which suggests that the degree of cognitive impairment in MCI may not influence the ability to learn skills in a therapeutic intervention [46, 47].

As an example how to tailor the therapy manuals to individuals with cognitive impairments, Tonga et al. described the experiences with and the required adjustments of a Cognitive Rehabilitation and Cognitive-behavioral treatment manual for early dementia in Alzheimer’s disease (CORDIAL) [72] within a case-control study with MCI and mild dementia patients [36]. The cognitive behavioral treatment with elements of cognitive rehabilitation and reminiscence methods were completed by homework assessments to promote transfer of novel behaviors into the everyday context. The authors stressed that it is crucial to be flexible with the manual regarding the individual needs of the patients and their caregivers and to consider the caregivers’ impact on completion of the homework and the adherence to the treatment. They concluded that therapists need to take into account possible disease-related barriers such as anosognosia or apathy, which might hinder treatment adherence; therefore, the patient’s motivation and disease awareness are even more important for ensuring treatment adherence, than the presence of a caregiver. Indeed, the patients’ insight into their cognitive impairments is a necessary requirement for a successful psychotherapy. Banningh et al. described that significant improvements of the insight into illness by MCI patients might be achieved by tailored cognitive behavioral therapies [63].

Early interventions in preclinical and prodromal AD within the scope of a treatment to improve mental health, disease-acceptance, and life quality might have a secondary effect in terms of slowing cognitive decline and therefore reducing the risk or delaying the onset of dementia. Several preventive non-pharmacological strategies have been conducted, some still ongoing, but there is still limited evidence to support a cause-effect relationship between a single preventive strategy such as physical exercise, stress reduction, nutrition, and treatment of psychiatric co-morbidities and the development or progression of dementia. There are several studies that followed a multifactorial intervention approach, including regular exercise and healthy diet, reduction of vascular risk factors, psychosocial stress, and major depressive episodes, amongst them the “Finnish Geriatric Intervention Study to Prevent Cognitive Impairment and Disability (FINGER),” the “Multidomain Alzheimer Preventive Trial (MAPT),” the “Prevention of Dementia by Intensive Vascular Care (preDIVA),” the “SCD-Well” trial as part of the “Medit-Ageing” project (Silver Santé Study), and the “Body, brain, life for cognitive decline (BBL-CD)” [13, 15–20, 68]. These interventions may be the most promising strategy for the prevention of cognitive decline and the development of individualized therapeutic interventions for the different stages of cognitive decline. However, only to a significantly lesser degree psychological risk factors and non-cognitive outcomes, such as mental health and quality of life, are primarily addressed in most of the prevention studies, leaving this field largely unexplored.

Mindfulness-based therapy, for instance, can help to promote acceptance and reduce maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies, such as ruminating. Especially acceptance-related non-judgment and non-reaction to irritative factors seem to alleviate psychological distress and may be an approach in interventions for individuals with SCD and even for MCI patients. Literature indicates that cognitive restructuring may reduce subjective memory complaints, whereas memory training may improve objective memory function [32, 33]. One way to promote these skills are mindfulness-based interventions, which have been developed from the mindfulness-based stress reduction program by Dr. Jon Kabat-Zinn [73]. There is data that MBSR is feasible in individuals with MCI and that the level of cognitive decline and memory impairment do not necessarily mean an inability to learn mindfulness intervention skills [46, 47]. Furthermore, MBSR has stress-reducing effects, improves well-being, and might improve acceptance and awareness of cognitive decline, which is of major concern for those facing cognitive decline and fear of developing dementia. In this context, the technique of expectancy modification [33] might be an interventional approach for treatment of individuals with SCD or MCI. The expectancy towards one’s own cognitive performance and cognitive competence can be improved by cognitive restructuring, e.g., during psychotherapeutic sessions, and psychoeducation by changing beliefs and attitudes about experienced memory impairment [33, 74]. Though existing quantitative data did not show significant effects on mood of MBSR-based interventions as compared to control conditions [46, 47, 55–58, 68, 69], additional qualitative data revealed positive findings on other outcomes, such as mindfulness skills, enhanced well-being, decreased stress reactivity, and increased relaxation [46, 47]. This leads to the phenomenon that findings from qualitative data, such as a high satisfaction and perceived benefit, are not mirrored in the quantitative assessments [75]. One explanation might be that subtle changes in mood or well-being might be missed by measurement with solely quantitative scales.

Overall, only limited conclusions about the efficacy of the cited studies can be drawn due to insufficiently rigorous study designs, short follow-up times, varying sample sizes ranging from 1 to 272, heterogeneous therapeutic techniques, and outcome measures. Findings on effects on mental health and well-being are therefore diverging and comparing the effects of different psychotherapeutic techniques as well as psychoeducational interventions on mood and quality of life is intricate. As some research groups report likewise effects of intervention and control conditions, it remains open, if the effects are attributable to specific types of interventions, treatment moderators, or other factors, such as participating in a study, interacting with a group, or being supported by a facilitator. Of note, in the cited papers, psychiatric comorbidities, such as depression or anxiety disorder, were exclusion criteria, and the majority of participants were not significantly depressed or anxious at baseline and well-being was generally rated medium to high; hence, there was little chance for the interventions to improve mood and well-being, as measured by quantitative scales. To conclude, the current literature reveals that approaches of psychotherapeutic and psychoeducational interventions are addressed in research projects and underline the feasibility of these interventions, but to date, robust data from RCT’s with large sample sizes providing evidence for significant therapeutic effects on mental health, quality of life and well-being are rare.

Given the strong evidence for psychoeducational interventions and psychotherapy in the field of psychiatric disorders and psychooncology, this field should be opened up systematically for neurodegenerative disorders, such as AD. Psychoeducation provides systematic disease-specific information, such as early recognition and management of disease symptoms, and general information, such as promotion of healthy lifestyle, improving self-management, and disease acceptance. Determinants of psychotherapy are, amongst others, resource activation, actualization of the patient’s problems, motivational clarification, and improving problem-solving skills. In the course of demographic changes, more emphasis should be placed on psychological conditions affecting the elderly, particularly on those who suffer from subjective or objective cognitive decline and actively seek professional help, as their perceived impairments may cause psychosocial stress and are often accompanied by the fear of dementia. A more holistic approach of preventive care with a stepped psychological-based AD management program for individuals which face AD diagnosis would therefore empower them to actively cope with their diagnosis and possible prognosis, than to wait for the disease progression. Moreover, these non-pharmacological interventions are associated with less side effects and are more cost-effective than medications. A future course of action in AD would be to arise awareness for the necessity of longitudinal RCT's addressing mental health and metacognitive abilities for individuals in preclinical and prodromal stages of AD that follow a mixed-method approach, with quantitative outcome measures and complementary qualitative evaluations to gain a deeper understanding of the benefits and possible limits of the interventions.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- ADL

Activities of daily living

- CBT

Cognitive behavioral therapy

- CORDIAL

Cognitive Rehabilitation and Cognitive-behavioral treatment for early dementia in Alzheimer disease

- DEMA

Daily Enhancement of Meaningful Activity

- e.g.

For example

- IPT

Interpersonal psychotherapy

- MBSR

Mindfulness based stress reduction

- MCI

Mild cognitive impairment

- MT

Mindfulness training

- n

Number

- NIA-AA

National Institute on Aging – Alzheimer's Association

- NPS

Neuropsychiatric symptoms

- PRISMA

Preferred reporting items of systematic review and meta-analyses

- PST

Problem-solving-therapy

- RCT

Randomized-controlled trial

- SCD

Subjective cognitive impairment

Authors’ contributions

AR, AK, and FK conducted the literature search and were responsible for literature review and data analysis. AR was responsible for the data interpretation and writing the article. FJ contributed to the conceptualization and review of drafts of the article. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. No funding was received for this publication.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

The original version of this article was revised: the authors noticed that first and family names of all authors were swapped.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

3/22/2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1186/s13195-022-00987-9

References

- 1.World Health Organisation. The epidemiology and impact of dementia: current state and future trends. First WHO Ministerial Conference on Global Action Against Dementia [Internet]. 2015;1–4. Available from: http://www.who.int/mental_health/neurology/dementia/thematic_briefs_dementia/en/

- 2.Albert MS, DeKosky ST, Dickson D, Dubois B, Feldman HH, Fox NC, et al. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on. Alzheimer’s & … [Internet]. 2011;7:270–9. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S155252601100104X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Jessen F, Amariglio RE, Van Boxtel M, Breteler M, Ceccaldi M. Ch??telat G, et al. A conceptual framework for research on subjective cognitive decline in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dementia. 2014;10:844–852. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jack CR, Bennett DA, Blennow K, Carrillo MC, Dunn B, Haeberlein SB, et al. NIA-AA research framework: toward a biological definition of alzheimer’s disease. alzheimer’s and dementia. elsevier inc.; 2018;14:535–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Wolfsgruber S, Polcher A, Koppara A, Kleineidam L, Frölich L, Peters O, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers and clinical progression in patients with subjective cognitive decline and mild cognitive impairment. J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2017;58:939–950. doi: 10.3233/JAD-161252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Maurik IS, Slot RER, Verfaillie SCJ, Zwan MD, Bouwman FH, Prins ND, et al. Personalized risk for clinical progression in cognitively normal subjects - the ABIDE project. Alzheimer’s Res Ther. 2019;11(1):33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Ebenau JL, Timmers T, Wesselman LMP, Verberk IMW, Verfaillie SCJ, Slot RER, et al. ATN classification and clinical progression in subjective cognitive decline: The SCIENCe project. Neurology. 2020;95(1):e46–e58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Mitchell AJ, Shiri-Feshki M. Rate of progression of mild cognitive impairment to dementia - meta-analysis of 41 robust inception cohort studies. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2009;119:252–265. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vos SJB, Verhey F, Fröhlich L, Kornhuber J, Wiltfang J, Maier W, et al. Prevalence and prognosis of Alzheimer’s disease at the mild cognitive impairment stage. Brain. 2015;138:1327–1338. doi: 10.1093/brain/awv029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barnes DE, Yaffe K. The projected effect of risk factor reduction on Alzheimer’s disease prevalence. Lancet Neurol. 2011. 819–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Livingston G, Sommerlad A, Orgeta V, Costafreda SG, Huntley J, Ames D, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. Lancet. 2017. 2673–734. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Sperling RA, Rentz DM, Johnson KA, Karlawish J, Donohue M, Salmon DP, et al. The A4 study: stopping AD before symptoms begin? Sci Transl Med. 2014;6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Ngandu T, Lehtisalo J, Solomon A, Levälahti E, Ahtiluoto S, Antikainen R, et al. A 2 year multidomain intervention of diet, exercise, cognitive training, and vascular risk monitoring versus control to prevent cognitive decline in at-risk elderly people (FINGER): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;385:2255–2263. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60461-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Norton S, Matthews FE, Barnes DE, Yaffe K, Brayne C. Potential for primary prevention of Alzheimer’s disease: an analysis of population-based data. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13:788–794. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70136-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coley N, Andrieu S. Lessons from the multidomain alzheimer preventive trial – authors’ reply. Lancet Neurol. 2017. p. 586. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Hooper C, de Souto Barreto P, Coley N, Cantet C, Cesari M, Andrieu S, et al. Cognitive changes with omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in non-demented older adults with low omega-3 index. J Nutrition Health Aging. 2017;21(9):988–93. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.de Souto BP, Andrieu S, Rolland Y, Vellas B. Physical activity domains and cognitive function over three years in older adults with subjective memory complaints: secondary analysis from the MAPT trial. J Sci Med Sport. 2018;21(1):52–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Rosenberg A, Ngandu T, Rusanen M, Antikainen R, Bäckman L, Havulinna S, et al. Multidomain lifestyle intervention benefits a large elderly population at risk for cognitive decline and dementia regardless of baseline characteristics: The FINGER trial. Alzheimer’s Dementia. 2018;14(3):263–70. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Richard E, Den Heuvel E Van, Moll Van Charante EP, Achthoven L, Vermeulen M, Bindels PJ, et al. Prevention of dementia by intensive vascular care (prediva): a cluster-randomized trial in progress. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Dis. 2009;23(3):198–204. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.McMaster M, Kim S, Clare L, Torres SJ, D’este C, Anstey KJ. Body, brain, life for cognitive decline (BBL-CD): protocol for a multidomain dementia risk reduction randomized controlled trial for subjective cognitive decline and mild cognitive impairment. Clin Interventions Aging. 2018;13:2397–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Dafsari FS, Jessen F. Depression—an underrecognized target for prevention of dementia in Alzheimer’s disease. Transl Psychiatry. 2020;10(1):160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Gulpers B, Ramakers I, Hamel R, Köhler S, Oude Voshaar R, Verhey F. Anxiety as a predictor for cognitive decline and dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Geriatric Psychiatry. 2016;24(10):823–42. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Pietrzak RH, Lim YY, Neumeister A, Ames D, Ellis KA, Harrington K, et al. Amyloid-β, anxiety, and cognitive decline in preclinical Alzheimer disease: a multicenter, prospective cohort study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(3):284–91. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Ismail Z, Smith EE, Geda Y, Sultzer D, Brodaty H, Smith G, et al. Neuropsychiatric symptoms as early manifestations of emergent dementia: provisional diagnostic criteria for mild behavioral impairment. Alzheimer’s Dementia. 2016;12:195–202. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2015.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gulpers BJA, Oude Voshaar RC, van Boxtel MPJ, Verhey FRJ, Köhler S. Anxiety as a risk factor for cognitive decline: a 12-year follow-up cohort study. Am J Geriatric Psychiatry. 2019;27(1):42–52. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Banningh LJW, Vernooij-Dassen M, Rikkert MO, Teunisse JP. Mild cognitive impairment: coping with an uncertain label. Int J Geriatric Psychiatry. 2008;23:148–154. doi: 10.1002/gps.1855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lingler JH, Nightingale MC, Erlen JA, Kane AL, Reynolds CF, Schulz R, et al. Making sense of mild cognitive impairment: a qualitive exploration of the patient’s experience. Gerontologist. 2006;46(6):791–800. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Bronner K, Perneczky R, McCabe R, Kurz A, Hamann J. Which medical and social decision topics are important after early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease from the perspectives of people with Alzheimer’s disease, spouses and professionals? BMC Research Notes [Internet]. BioMed Central; 2016;9:149. Available from: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1756-0500/9/149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Faller H, Steinbüchel T, Schowalter M, Spertus JA, Störk S, Angermann CE. The Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ) - a new disease-specific quality of life measure for patients with chronic heart failure: Psychometric evaluation of the German version. Psychosomatik, medizinische Psychologie: Psychotherapie. 2005;55(3-4):200–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Rodakowski J, Saghafi E, Butters MA, Skidmore ER. Non-pharmacological interventions for adults with mild cognitive impairment and early stage dementia: an updated scoping review. Molecular Aspects Med. 2015;43-44:38–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Horr T, Messinger-Rapport B, Pillai JA. Systematic review of strengths and limitations of randomized controlled trials for non-pharmacological interventions in mild cognitive impairment: focus on Alzheimer’s disease. Health Aging J Nutrition. 2015;19(2):141–53. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Smart CM, Karr JE, Areshenkoff CN, Rabin LA, Hudon C, Gates N, et al. Non-pharmacologic interventions for older adults with subjective cognitive decline: systematic review, meta-analysis, and preliminary recommendations. Neuropsychol Rev. 2017;27(3):245–57. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Metternich B, Kosch D, Kriston L, Härter M, Hüll M. The effects of nonpharmacological interventions on subjective memory complaints: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychother Psychosomatics. 2009;79(1):6–19. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.The Prisma Group from Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J AD. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med [Internet]. 2009;6:1–15. Available from: www.prisma-ststement.org [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Petersen RC. Mild cognitive impairment as a clinical entity and treatment target. Arch Neurol. 2004;62:1160–1163. doi: 10.1001/archneur.62.7.1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tonga JB, Karlsoeen BB, Arnevik EA, Werheid K, Korsnes MS, Ulstein ID. Challenges with manual-based multimodal psychotherapy for people with Alzheimer’s disease: a case study. Am J Alzheimer’s Dis Dementias. 2016;31:311–317. doi: 10.1177/1533317515603958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scheurich A. Schanz B. Fellgiebel A. Gruppentherapeutische frühintervention für patienten im frühstadium der Alzheimererkrankung und deren angehörige - Eine pilotstudie. PPmP Psychotherapie Psychosomatik Medizinische Psychologie: Müller MJ; 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kurz A, Pohl C, Ramsenthaler M. Sorg C. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry: Cognitive rehabilitation in patients with mild cognitive impairment; 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tonga JB, Šaltytė Benth J, Arnevik EA, Werheid K, Korsnes MS, Ulstein ID. Managing depressive symptoms in people with mild cognitive impairment and mild dementia with a multicomponent psychotherapy intervention: a randomized controlled trial. International Psychogeriatrics. 2021. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Jessen F, Amariglio RE, van Boxtel M, Breteler M, Ceccaldi M, Chetelat G, et al. A conceptual framework for research on subjective cognitive decline in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dementia. United States. 2014;10:844–852. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hawker S, Payne S, Kerr C, Hardey M, Powell J. Appraising the evidence: reviewing disparate data systematically. Qualitative Health Research. 2002;12:1284–1299. doi: 10.1177/1049732302238251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Miller MD, Reynolds CF. Expanding the usefulness of Interpersonal Psychotherapy (IPT) for depressed elders with co-morbid cognitive impairment. Int J Geriatric Psychiatry. 2007;22(2):101–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Gildengers, M.A. B, S.M. A, S.J. A, M.A. D, K. E, et al. Design and implementation of an intervention development study: retaining cognition while avoiding late-life depression (ReCALL). Am J Geriatric Psychiatry. 2016;24(6):444–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Lu YYF, Haase JE. Weaver M. Journal of Gerontological Nursing: Pilot testing a couples-focused intervention for mild cognitive impairment. 2013;39(5):16–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Lu YYF, Ellis J. Yang Z. Bakas T, Austrom MG, et al. Satisfaction with a family-focused intervention for mild cognitive impairment dyads. Journal of Nursing Scholarship: Weaver MT. 2016;48(4):334–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Wells RE, Kerr CE, Wolkin J, Dossett M, Davis RB, Walsh J, et al. Meditation for adults with mild cognitive impairment: a pilot randomized trial. J Am Geriatrics Soc. 2013;61(4):642–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Wells RE, Kerr C, Dossett ML, Danhauer SC, Sohl SJ, Sachs BC, et al. Can adults with mild cognitive impairment build cognitive reserve and learn mindfulness meditation? Qualitative theme analyses from a small pilot study. J Alzheimer’s Disease. 2019;70(3):825–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Rovner BW, Casten RJ, Hegel MT, Leiby BE. Preventing cognitive decline in older African Americans with mild cognitive impairment: design and methods of a randomized clinical trial. Contemporary Clinical Trials. 2012;33(4):712–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Rovner BW, Casten RJ, Hegel MT, Leiby B. Preventing cognitive decline in black individuals with mild cognitive impairment: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 2018;75(12):1487–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Schmitter-Edgecombe M, Dyck DG. Cognitive rehabilitation multi-family group intervention for individuals with mild cognitive impairment and their care-partners. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2014;20(9):897–908. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Rovner BW, Casten RJ. Preserving cognition in older african americans with mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatrics Soc. 2016;64(3):659–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Smith G, Chandler M, Locke DE, Fields J, Phatak V, Crook J, et al. Behavioral interventions to prevent or delay dementia: protocol for a randomized comparative effectiveness study. JMIR Res Protoc. 2017;6(11):e223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Chandler MJ, Locke DE, Crook JE. Fields JA. Phatak VS, et al. Comparative effectiveness of behavioral interventions on quality of life for older adults with mild cognitive impairment a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Network Open: Ball CT. 2019;2(5):e193016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.Ellis JL, Altenburger P, Lu Y. Change in depression, confidence and physical function among older adults with mild cognitive impairment. 2019;42(3):E108–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.Smart CM, Segalowitz SJ, Mulligan BP, Koudys J, Gawryluk JR. Mindfulness training for older adults with subjective cognitive decline: results from a pilot randomized controlled trial. J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2016;52(2):757–74. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 56.Smart CM, Segalowitz SJ. Respond, don’t react: The influence of mindfulness training on performance monitoring in older adults. Affective and Behavioral Neuroscience: Cognitive. 2017;17(6):1151–63. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 57.Larouche E, Hudon C, Goulet S. Mindfulness mechanisms and psychological effects for aMCI patients: a comparison with psychoeducation. Complementary Therapies Clin Practice. 2019;34:93–104. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 58.Chouinard AM, Larouche E, Audet MC, Hudon C, Goulet S. Mindfulness and psychoeducation to manage stress in amnestic mild cognitive impairment: a pilot study. Aging Mental Health. 2019;23(9):1246–54. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 59.Bier N, Grenier S, Brodeur C, Gauthier S, Gilbert B, Hudon C, et al. Measuring the impact of cognitive and psychosocial interventions in persons with mild cognitive impairment with a randomized single-blind controlled trial: rationale and design of the MEMO+ study. International Psychogeriatrics. 2015;27(3):511–25. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 60.Belleville S, Hudon C, Bier N, Brodeur C, Gilbert B, Grenier S, et al. MEMO+: efficacy, durability and effect of cognitive training and psychosocial intervention in individuals with mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatrics Soc. 2018;66(4):655–63. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 61.Hoogenhout EM, De Groot RHM, Van Der Elst W, Jolles J. Effects of a comprehensive educational group intervention in older women with cognitive complaints: a randomized controlled trial. Aging Mental Health. 2012;16(2):135–44. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 62.Joosten-Weyn Banningh LWA, Prins JB, Vernooij-Dassen MJFJ, Wijnen HH, Olde Rikkert MGM, Kessels RPC. Group therapy for patients with mild cognitive impairment and their significant others: results of a waiting-list controlled trial. Gerontology. 2011;57(5):444–54. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 63.Joosten-Weyn Banningh LWA, Roelofs SCF, Vernooij-Dassen MJFJ, Prins JB, Olde Rikkert MGM, Kessels RPC. Long-term effects of group therapy for patients with mild cognitive impairment and their significant others: a 6- to 8-month follow-up study. Dementia. 2013;12(1):81–91. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 64.Joosten-Weyn Banningh LWA, Kessels RPC, Olde Rikkert MGM, Geleijns-Lanting CE, Kraaimaat FW. A cognitive behavioural group therapy for patients diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment and their significant others: feasibility and preliminary results. Clinical Rehabilitation. 2008;22(8):731–40. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 65.Diamond K, Mowszowski L, Cockayne N, Norrie L, Paradise M, Hermens DF, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a healthy brain ageing cognitive training program: effects on memory, mood, and sleep. J Alzheimer’s Disease. 2015;44(4):1181–91. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 66.Cohen-Mansfield J, Cohen R, Buettner L, Eyal N, Jakobovits H, Rebok G, et al. Interventions for older persons reporting memory difficulties: a randomized controlled pilot study. Int J Geriatric Psychiatry. 2015;30(5):478–86. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 67.Barton K, Johnson I, Mountford A. Development of a psychosocial group intervention for individuals with mild cognitive impairment (innovative practice). Dementia. 2017;19(4):1325–32. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 68.Marchant NL, Barnhofer T, Klimecki OM, Poisnel G, Lutz A, Arenaza-Urquijo E, et al. The SCD-Well randomized controlled trial: effects of a mindfulness-based intervention versus health education on mental health in patients with subjective cognitive decline (SCD). Translational Research and Clinical Interventions: Alzheimer’s Dementia. 2018;4:737–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 69.Marchant NL, Barnhofer T, Coueron R, Wirth M, Lutz A, Arenaza-Urquijo EM, et al. Effects of a Mindfulness-based intervention versus health self-management on subclinical anxiety in older adults with subjective cognitive decline: the SCD-well randomized superiority trial. Psychotherapy Psychosomatics. 2021;90(5):341–50. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 70.Belleville S, Gilbert B, Fontaine F, Gagnon L, Ménard É, Gauthier S. Improvement of episodic memory in persons with mild cognitive impairment and healthy older adults: evidence from a cognitive intervention program. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2006;22(5-6):486–99. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 71.Rakesh G, Szabo ST, Alexopoulos GS, Zannas AS. Strategies for dementia prevention: latest evidence and implications. Therapeutic Adv Chronic Dis. 2017;8(8-9):121–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 72.Alexander Kurz C, Tho A, Cramer B, Egert S, Fro L, Gertz H-J, et al. CORDIAL: cognitive rehabilitation and cognitive-behavioral treatment for early dementia in Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2012;26(3):246–53. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 73.Kabat-Zinn J. Full catastrophe living: the program of the stress reduction clinic at the University of Massachusetts Medical Center. The Nurse Practitioner. 1990;00221287–136.

- 74.Lachman ME, Weaver SL, Bandura M, Elliott E, Lewkowicz CJ. Improving memory and control beliefs through cognitive restructuring and self-generated strategies. J Gerontol. 1992;47(5):P293–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 75.Moffatt S, White M, Mackintosh J, Howel D. Using quantitative and qualitative data in health services research - what happens when mixed method findings conflict? [ISRCTN61522618]. BMC Health Serv Res. 2006;6:28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 76.Zellner Keller B, Singh NN, Winton ASW. Mindfulness-based cognitive approach for seniors (MBCAS): program development and implementation. Mindfulness. 2014;5(4):453–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.