Abstract

The first outbreak caused by vancomycin-resistant enterococci of the VanB phenotype in Poland was analyzed. It occurred in a single ward of a Warsaw hospital which is a specialized center for the treatment of hematological disorders. Between July 1999 and February 2000, 11 patients in the ward were found to be infected and/or colonized by Enterococcus faecium that was resistant in vitro to vancomycin and susceptible to teicoplanin. PCR analysis confirmed that the vancomycin-resistant E. faecium (VREM) isolates carried the vanB gene, which is responsible for the VanB phenotype. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) typing revealed that the isolates belonged to four distinct PFGE types and that one of these was clearly predominant, including isolates collected from seven different patients. The isolates contained one or more copies of the vanB gene cluster of the identical, unique DraI/PagI (BspHI) restriction fragment length polymorphism type, which resided in either the same or different plasmid molecules or chromosomal regions. All this data suggested that the outbreak was due to both clonal spread of a single strain and horizontal transfer of resistance genes among nonrelated strains, which could be mediated by plasmids and/or by vanB gene cluster-containing transposons. The comparative analysis of vancomycin-susceptible E. faecium (VSEM) isolates collected from infections in the same ward at the time of the VREM outbreak has led to identification of a widespread VSEM strain that was possibly related to the major VREM clone. It is very likely that this endemic VSEM strain has acquired vancomycin-resistance determinants and that the acquisition occurred more than once during the outbreak.

Vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) belong nowadays to the most important nosocomial pathogens worldwide (23, 25), and they usually cause infections in severely debilitated, immunocompromised patients who undergo prolonged and intensive antibiotic therapy (21, 24). The first VRE strains, Enterococcus faecium and Enterococcus faecalis, were isolated in 1986 in France (19) and in the United Kingdom (38), and since then they have been identified in many other countries (1, 7, 22, 35). In some countries VRE may significantly contribute to enterococcal populations circulating in hospitals; recently in the United States the prevalence of vancomycin-resistant E. faecium (VREM) isolates was estimated at the level of 15% of nosocomial isolates of this species (3).

Out of five different VRE phenotypes that are known to date, the so-called phenotypes VanA and VanB were identified first and they have remained the most important from the clinical point of view (13, 19, 20, 28, 32). The VanB phenotype originally reported in 1989 (33) is characterized by high-level resistance to vancomycin and susceptibility to teicoplanin (32). It is determined by a cluster of genes, vanRB, -SB, -YB, -W, -HB, -B, and -XB, which usually reside within composite transposons like Tn1547 and similar elements (11, 31). Sequencing of numerous copies of the vanB gene has revealed a certain degree of its structural diversity, and three main gene variants, vanB1, vanB2, and vanB3, have been distinguished to date (7, 14, 27). In contrast to VanA enterococci, only a few VRE outbreaks have been attributed to microorganisms with the phenotype VanB, and these were caused either by the horizontal transfer of resistance determinants among nonrelated strains (4, 5, 30, 40) or by the clonal spread of epidemic strains (6, 10, 35, 37).

The first reported identification of VRE in Poland occurred at the end of 1996 in a hospital in Gdańsk with the isolation of E. faecium of the phenotype VanA, and it was followed by a large VRE outbreak in this center (15, 16, 34). In mid-1999 the first VREM strains with the phenotype VanB were identified in two hospitals in Warsaw, Poland. In one hospital it was a sporadic case of selection restricted to a single patient (17), whereas in the second hospital a VREM outbreak started at that time and lasted until the beginning of 2000. In this study we present results of the analysis of this outbreak which, to date, has been the only outbreak caused by enterococci of the VanB phenotype identified in Poland.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Clinical isolates.

Thirteen VREM isolates were recovered from patients in a single ward of the Institute of Hematology and Blood Transfusion in Warsaw between July 1999 and February 2000 (Table 1). Nine VREM isolates were collected from infection sites of eight different patients, and these were cultured from Broviac-type central catheters, blood, and urine samples. The remaining isolates were identified from the stool of four colonized patients, only one of whom was also infected (altogether, three isolates from this patient, no. 464, 465, and 466, were included in the study). The carriage testing was performed with the use of bile-esculin agar (Oxoid, Basingstoke, United Kingdom) plates supplemented with 10 μg of colistin (Polfa Tarchomin, Warsaw, Poland)/ml, 10 μg of nalidixic acid (Sigma Chemical Company, St. Louis, Mo.)/ml, and 6 μg of vancomycin (Eli Lilly, Indianapolis, Ind.)/ml.

TABLE 1.

Data on clinical isolates and MICs of antimicrobial agents

| Isolatea | Phenotype | Sourceb | Mo/yr of isolation | Matingc | PFGE typing | L-PCRd | REAP | Tn1547 locuse | MIC (μg/ml)f

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEN | AMP | GEN | STR | VAN | TEC | CHL | TET | CIP | |||||||||

| 8284 | VREM | i | 07/99 | − | a1 | + | A1 | I | 128 | 32 | >1,024 | >2,048 | 128 | 1 | 32 | 64 | 64 |

| 8309 | VREM | i | 08/99 | + | a2 | + | A2 | I | 128 | 64 | >1,024 | >2,048 | 256 | 1 | 32 | 64 | 128 |

| 8310 | VREM | i | 08/99 | − | b1 | + | A3 | II | >128 | 128 | >1,024 | >2,048 | 256 | 0.5 | 32 | 128 | 128 |

| 8841 | VREM | i | 09/99 | − | b3 | + | A3 | II | >128 | 64 | 256 | >2,048 | 128 | 0.25 | 32 | 32 | 64 |

| 8967 | VREM | i | 10/99 | + | c | + | B | II | 128 | 64 | >1,024 | >2,048 | 128 | 0.25 | 16 | 32 | 32 |

| 247 | VREM | i | 01/00 | − | b2 | + | C | II | >128 | 128 | 64 | >2,048 | 512 | 4 | 32 | 1 | 512 |

| 343 | VREM | i | 02/00 | − | b3 | − | A3 | II | >128 | 128 | >1,024 | >2,048 | 256 | 1 | 16 | 128 | 512 |

| 463 | VREM | c | 02/00 | − | b4 | + | A4 | II | >128 | 128 | >1,024 | >2,048 | 256 | 1 | 32 | 128 | 512 |

| 464 | VREM | i | 02/00 | − | b3 | − | A3 | II | >128 | 64 | >1,024 | >2,048 | 128 | 1 | 16 | 128 | 512 |

| 465 | VREM | i | 02/00 | − | b5 | − | A5 | II | 128 | 64 | >1,024 | >2,048 | 256 | 1 | 16 | 128 | 256 |

| 466 | VREM | c | 02/00 | − | b3 | − | A5 | II | >128 | 128 | >1,024 | >2,048 | 256 | 1 | 16 | 64 | 512 |

| 504 | VREM | c | 02/00 | + | d | + | D | II | >128 | 128 | >1,024 | 512 | 256 | 1 | 16 | 128 | 512 |

| 507 | VREM | c | 02/00 | − | b4 | − | A4 | II | >128 | 128 | >1,024 | >2,048 | 256 | 1 | 16 | 256 | 512 |

| 8051 | VSEM | i | 06/99 | − | b9 | ND | ND | ND | >128 | 64 | >1,024 | >2,048 | 2 | 1 | 16 | 128 | 256 |

| 8639 | VSEM | i | 09/99 | − | b8 | ND | ND | ND | >128 | 64 | >1,024 | >2,048 | 1 | 0.5 | 32 | 0.5 | 128 |

| 8843 | VSEM | i | 09/99 | − | b7 | ND | ND | ND | >128 | 64 | >1,024 | >2,048 | 1 | 0.125 | 16 | 0.5 | 64 |

| 9304 | VSEM | i | 10/99 | − | b10 | ND | ND | ND | >128 | 64 | >1,024 | >2,048 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 8 | 0.25 | 32 |

| 9387 | VSEM | i | 11/99 | − | b6 | ND | ND | ND | >128 | 64 | >1,024 | >2,048 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 8 | 256 | 128 |

| 96 | VSEM | i | 12/99 | − | b7 | ND | A5 | ND | >128 | >128 | >1,024 | >2,048 | 1 | 0.5 | 32 | 1 | 128 |

Isolates 464, 465, and 466 were recovered from a single patient.

i, infection; c, carriage.

+ and − indicate isolates that produced and did not produce transconjugants, respectively.

+ and − indicate isolates that produced and did not produce L-PCR product specific for the vanB gene cluster, respectively; ND, not detected.

Polymorphism of Tn1547-like insertion loci.

PEN, penicillin; AMP, ampicillin; GEN, gentamicin; STR, streptomycin; VAN, vancomycin; TEC, teicoplanin; CHL, chloramphenicol; TET, tetracycline; CIP, ciprofloxacin.

Fourteen vancomycin-susceptible E. faecium (VSEM) isolates were included in the analysis, and these were all VSEM isolates identified as etiologic agents of infections in the same ward between June and December 1999. They were recovered from different patients than those from whom VREM isolates were derived.

Genus identification of the isolates was performed according to Facklam and Collins (12), and the species were identified using the API ID32 STREP test (bioMérieux, Charbonnieres-les-Bains, France), supplemented by potassium tellurite reduction and motility and pigment production tests (12).

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

MICs of different antimicrobial agents were evaluated by the agar-dilution method according to the NCCLS guidelines (26). The following agents were tested: penicillin, ampicillin, streptomycin, gentamicin, tetracycline, and chloramphenicol (Polfa Tarchomin), vancomycin (Eli Lilly), teicoplanin (Marion Merrell, Denham, United Kingdom), and ciprofloxacin (Bayer, Wuppertal, Germany). E. faecalis ATCC 29212, Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 29213, and the E. faecalis V583 VanB standard strain (11, 33) were used as reference strains.

Resistance transfer (mating).

The vancomycin-resistance transfer experiment was performed using the filter-mating procedure (18) with the E. faecium 64/3 strain resistant to rifampin and fusidic acid (39) as a recipient. Transconjugants were selected on brain heart infusion agar (Oxoid) plates containing 64 μg of rifampin (Polfa Tarchomin)/ml, 64 μg of fusidic acid (Leo Pharmaceutical Products, Ballerup, Denmark)/ml, and 32 μg of vancomycin (Eli Lilly)/ml.

PFGE typing.

Genomic DNA preparations of the isolates, embedded in 0.75% agarose plugs (InCert Agarose; FMC Bioproducts, Rockland, Maine), were digested with the SmaI restriction enzyme (Takara, Otsu, Japan) and were separated in 1% agarose gel (Pulsed Field-Certified; Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.) by using a CHEF DRII system (Bio-Rad). DNA was purified as reported by Clark et al. (7), and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) was run under conditions described by de Lencastre et al. (9). Results were interpreted according to Tenover et al. (36).

Detection of the vanB gene.

Total DNAs of the isolates were obtained using a Genomic DNA Prep Plus kit (A&A Biotechnology, Gdańsk, Poland), and the vanB gene was detected by specific PCR with primers “vanB” (7) in a GeneAmp 2400 thermocycler (Perkin-Elmer, Norwalk, Conn.). Genomic DNA purified from the E. faecalis V583 VanB standard strain (11, 33) was used as a positive control, whereas DNA of the E. faecalis ATCC 29212 strain served as a negative control.

Restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis of the vanB gene cluster.

DNA fragments containing clusters of vanRB, -SB, -YB, -W, -HB, -B, and -XB, genes were amplified from total DNA of the isolates by long PCR (L-PCR) with the use of primers “vanB long” and the procedure by Dahl et al. (8). The resulting L-PCR products were digested with DraI and PagI (isoschizomer of BspHI) restriction enzymes (MBI Fermentas, Vilnius, Lithuania) and electrophoresed in 1% agarose gels (SeaKem; FMC Bioproducts). Genomic DNA of the E. faecalis V583 VanB standard strain (11, 33) was used as a positive control.

Restriction endonuclease analysis of plasmids (REAP) and RFLP analysis of the vanB gene cluster locus.

Plasmid DNA was purified from lysozyme-treated bacterial cells (0.5 mg/ml; Sigma Chemical Company) by the alkaline lysis method (2) using a QIAGEN Plasmid Midi Kit (Hilden, Germany). DNA preparations were digested with DraI and PagI restrictases (MBI Fermentas), separated in 1% agarose gels (SeaKem; FMC Bioproducts), and blotted onto a Hybond-N+ membrane (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom) for hybridization with the vanB gene cluster probe. The L-PCR amplicon of the vanB cluster present in the E. faecalis V583 VanB reference strain (11, 31) was used as the probe. Probe labeling, hybridization, and signal detection were performed with an ECL Random-Prime labeling and detection system (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). Genomic DNA isolated from the E. faecalis V583 strain (11, 31) was used as a positive control.

The SmaI (Takara)-digested total DNA of the isolates was separated by PFGE (as described above), blotted onto the Hybond-N+ membrane (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech), and hybridized with the vanB gene cluster probe (performed as described above). Total DNA of the E. faecalis V583 strain (11, 31) served as a positive control of hybridization.

RESULTS

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing of the VREM isolates.

MICs of various antimicrobial agents for the 13 VREM isolates are presented in Table 1. All the isolates demonstrated a high level of resistance to vancomycin (MICs, 128 to 512 μg/ml) and susceptibility to teicoplanin (MICs, 0.25 to 4 μg/ml). They were also uniformly resistant to penicillin, ampicillin, ciprofloxacin, and to high concentrations of aminoglycosides and were nonsusceptible to chloramphenicol. All but one isolate were resistant to tetracycline.

PFGE typing of the VREM isolates.

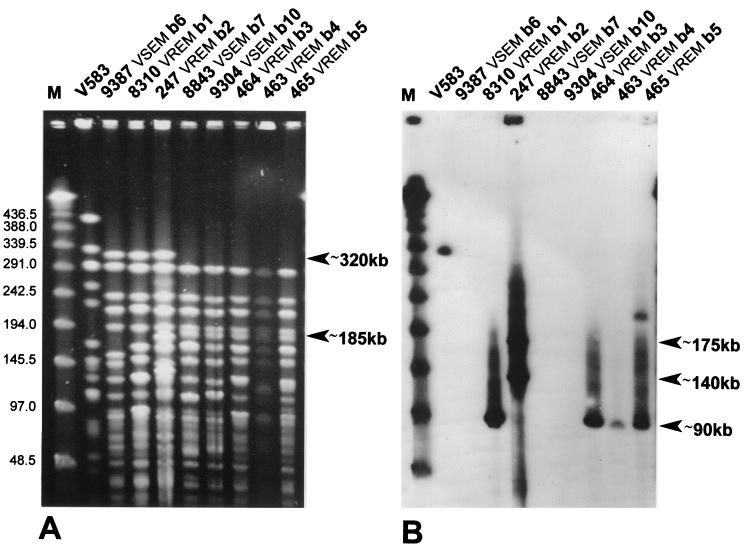

Results of the analysis are shown in Table 1; Fig. 1 contains the PFGE patterns of five selected isolates. Four different PFGE types (36) were distinguished among the VREM isolates. One of these, PFGE type b, was markedly predominant, as it was represented by nine isolates recovered from seven different patients. These isolates could be further classified into subtypes (36) b1 to b5, with four isolates from three patients included in the subtype b3. All isolates of the PFGE type b formed two general similarity groups based on some characteristics of their DNA banding patterns. Only isolates of subtypes b1 and b2 produced the biggest DNA band observed among the type b isolates of about 320 kb, whereas isolates of subtypes b3 to b5 were characterized by another specific DNA band of about 185 kb. The first two VREM isolates identified (8284 and 8309) revealed PFGE patterns designated as PFGE subtypes a1 and a2. The remaining two isolates (8967 and 504) belonged to unique PFGE type c and d.

FIG. 1.

PFGE analysis of selected type b VREM and VSEM isolates (A) and hybridization of the PFGE-separated DNA with the vanB gene cluster probe (B). M, λ ladder DNA molecular weight standard (New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.). DNA bands that differentiated two similarity groups of PFGE type b-specific patterns, as well as bands that hybridized with the probe, are indicated.

Vancomycin-resistance transfer and susceptibility testing of transconjugant strains.

Results of mating are presented in Table 1. Only three VREM isolates produced vancomycin-resistant transconjugants, and the efficiency of conjugation was low, ranging from 10−7 to 10−9 per donor cell. Susceptibility testing revealed that some other resistance determinants were cotransferred with the vancomycin resistance. Transconjugants of the isolates 8309 and 8967 were found to be resistant to tetracycline, the transconjugant of the isolate 504 demonstrated high-level resistance to streptomycin, and the transconjugant of the isolate 8967 revealed resistance to high concentrations of both aminoglycosides tested (data not shown).

Detection of the vanB gene.

The vanB gene detection was carried out with the use of primers “vanB” (7) that are specific for the vanB1 gene variant (8). PCR products of the expected size of about 450 bp were obtained for all the VREM isolates (results not shown).

RFLP analysis of the vanB gene cluster.

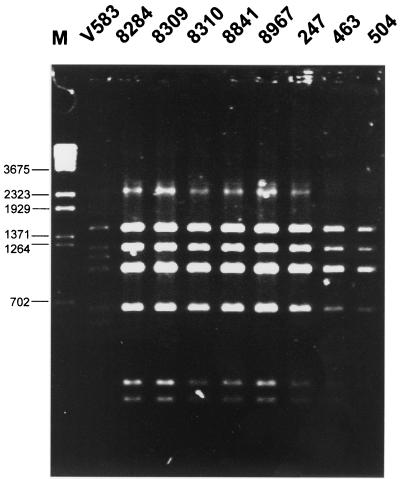

DNA fragments encompassing the vanB gene cluster regions were amplified by L-PCR, and products of the expected size of about 6 kb were obtained for 8 of 13 VREM isolates (Table 1). Results of their restriction analysis with the use of DraI and PagI (BspHI) enzymes are shown in Fig. 2. The amplified fragments produced the identical RFLP pattern, which was different from that specific for the original vanB gene cluster present in the E. faecalis V583 strain (8, 31).

FIG. 2.

RFLP analysis of the vanRSYWHBX region digested with DraI and PagI (BspHI). M, λ/BstEII DNA molecular weight standard (Kucharczyk TE, Warsaw, Poland).

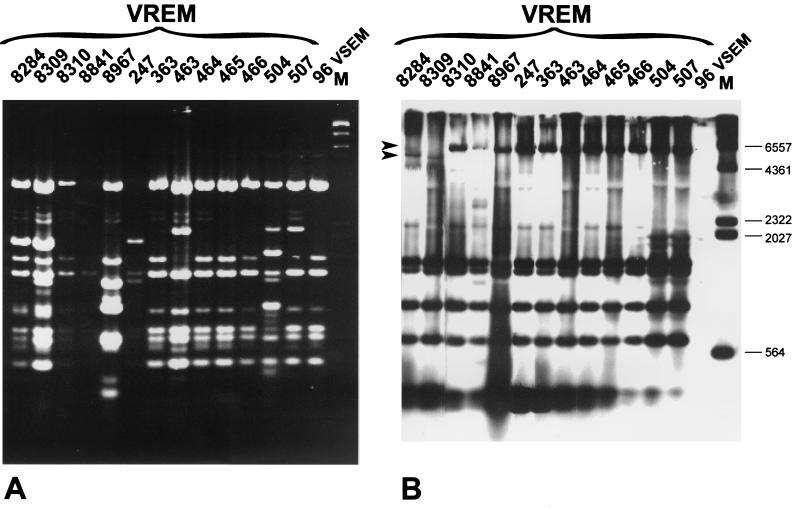

REAP and RFLP analysis of the vanB gene cluster locus.

Results of the analyses are shown in Table 1 and Fig. 3. Plasmids purified from VREM isolates and digested with DraI and PagI (BspHI) restriction enzymes were electrophoresed (REAP) and subsequently hybridized with the vanB gene cluster probe (analysis of the vanB cluster locus RFLP). The REAP patterns were found to be complex, as at least a significant fraction of the isolates contained multiple plasmid molecules of different sizes and abundance in their cells. The majority of isolates were characterized by either identical or very similar composition of plasmids (REAP patterns A1 to A5); however, even those isolates, which produced clearly distinct REAP patterns (REAP patterns B, C, and D), shared with all the others the same or related molecules. Results of the RFLP analysis of the vanB gene cluster locus are presented in Table 1 and Fig. 3. Hybridization patterns were obtained for all the VREM isolates, including those which had not produced the vanB gene cluster-containing L-PCR amplicons. Strikingly, the hybridizing bands could not be assigned to plasmid DNA restriction fragments visualized in REAP. Eleven isolates, including all isolates of PFGE types b, c, and d, were characterized by the same polymorph of the vanB gene cluster locus (RFLP, type II). The RFLP pattern specific for the two remaining isolates of PFGE type a (RFLP, type I) differed from the predominant one by faster migration of the biggest DNA restriction fragment.

FIG. 3.

REAP analysis (A) and hybridization of plasmid DNA digested with DraI and PagI (BspHI) with the vanB gene cluster probe (B). M, λ/HindIII DNA molecular weight standard (Kucharczyk TE, Warsaw, Poland). Arrows indicate DNA bands that differentiated the type I and type II polymorphs of the Tn1547-like element insertion locus.

The vanB gene cluster probe was also used in hybridization with the SmaI-digested total DNA of the isolates separated by PFGE. Figure 1 shows results obtained for five selected isolates. A single hybridizing DNA band of about 90 kb was revealed for all but five VREM isolates, which belonged to PFGE types b and d. In the case of PFGE types b5 and c isolates, this band was accompanied by another one of about 210 and 120 kb, respectively. For the three remaining isolates (PFGE types a and b2), two or more bands of different sizes and hybridization intensity (from about 140 kb to about 350 kb) were observed.

Epidemiological analysis of the VSEM isolates.

Identification of numerous VREM isolates in the single ward of the hematological hospital in Warsaw prompted us to investigate their relatedness to VSEM strains that were present in the ward at the same time. Fourteen VSEM isolates, recovered from infections in the second half of 1999, were typed by PFGE along with all VREM isolates. Figure 1 presents PFGE patterns produced by three representative VSEM isolates and compares them with five selected VREM isolates. Altogether, six VSEM isolates were characterized by similar PFGE patterns and these were classified into PFGE type b, distinguished previously to include nine VREM isolates (Table 1). The VSEM-specific PFGE subtypes b6 to b10 also could be split into two general similarity groups that were observed before among VREM PFGE subtypes b1 to b5. The VSEM PFGE subtype b6 was similar to VREM subtypes b1 and b2, whereas the VSEM subtypes b7 to b10 resembled rather the VREM subtypes b3 to b5. Hybridization with the vanB gene cluster probe (Fig. 1) revealed that DNA bands that contained the vancomycin-resistance genes belonged to those for which PFGE patterns characteristic for VREM isolates differed from their VSEM-specific counterparts. Plasmid DNA purified from a single VSEM isolate (isolate 96 of the PFGE subtype b7) was subjected to restriction analysis together with plasmids obtained from VREM isolates (Table 1 and Fig. 3). The DraI/PagI (BspHI) REAP pattern produced by the isolate was found to be identical to the variant characteristic for two VREM isolates (isolates 465 and 466 of PFGE subtypes b5 and b3, respectively).

The antimicrobial susceptibility testing revealed that the PFGE type b VSEM isolates were multiresistant (Table 1). In addition to glycopeptides (vancomycin MICs, 0.5 to 2 μg/ml; teicoplanin MICs, 0.125 to 1 μg/ml), the majority of these isolates were susceptible only to tetracycline.

DISCUSSION

The Institute of Hematology in Warsaw is a relatively small medical institution (200 beds) that specializes in the treatment of patients suffering from different types of hematological disorders. The VREM outbreak was restricted to its single ward (40 beds), which admits mainly hematological patients for repetitive short-term chemotherapy courses and neutropenic patients with infection symptoms who are usually hospitalized for prolonged periods and are intensively treated with antimicrobial agents. The antibiotic consumption is very high in the ward and includes those agents which are not active against enterococci due to their natural or broad acquired resistance. During the last 4 months of 1999, the mean monthly number of defined daily doses (DDDs) prescribed was 298 DDDs of expanded-spectrum cephalosporins, 264 DDDs of antianaerobic agents (amoxycillin with clavulanate, ampicillin with sulbactam, piperacillin with tazobactam, clindamycin, and metronidazole), and 273 DDDs of cotrimoxazole. The monthly DDDs number of 28 reflected the consumption of vancomycin in the same period. Considering the mean number of patients in the ward per month as 250, it means that one patient was treated monthly with 3.5 DDDs of these antimicrobials, whereas the mean hospitalization time was 5 days. Enterococci are among the most prevalent pathogens in the ward; between June and December 1999 enterococcal infections constituted 22.5% (n = 25) of all infections identified, and E. faecium was responsible for 76.0% of these (n = 19). All these factors have created a high-risk background for selection and spread of VRE strains, and especially VREM.

The outbreak was caused by VREM of the VanB phenotype, and together with the emergence of a VREM strain in another Warsaw hospital at the same time (17), these represented the first incidences of VanB enterococci reported in Poland. Strains identified in both centers were selected independently and were not transmitted from one hospital to the other. Detection of the vanB gene by PCR with the primers “vanB” designed by Clark et al. (7) suggested that the gene variant present in the outbreak isolates was vanB1 (8). The RFLP analysis of the vanB gene cluster and its locus revealed that all the isolates contained the same DraI/PagI (BspHI) polymorph of the cluster. (However, some cluster sequence diversity must have occurred among the isolates, as was demonstrated by the failure of L-PCR amplification of the region in five isolates.) The polymorph was found to be different from those identified up to now (8), and strikingly it seemed to be more related to the polymorph RFLP-2, correlating with vanB2 and -B3 gene variants, than to RFLP-1, which has been observed as vanB1 specific to date (8).

The PFGE analysis revealed a certain degree of clonal diversity of the outbreak isolates. Four different PFGE types of isolates were distinguished, and two of these, PFGE types a and b, were represented by more than one isolate. The first two VREM isolates identified belonged to the PFGE type a; however, during the outbreak the PFGE type b became clearly predominant, in 9 of 13 isolates that were collected. The PFGE type b VREM isolates formed five distinct subtypes, which could be classified into two general similarity groups. This data suggested that the outbreak was mostly clonal and that the main epidemic VREM strain was undergoing a rapid evolutionary differentiation due to various genetic events. Nevertheless, it is also very likely that, at least to some extent, the observed diversity of the PFGE type b E. faecium population existed before the emergence of vancomycin-resistance genes in the enterococcal population of the hospital (discussed below).

Identification of VREM isolates belonging to PFGE types a, c, and d, as well as the diversity of the PFGE type b isolates, raised the problem of the origin of vancomycin-resistance determinants in the enterococcal population of the hospital. As was mentioned above, the vanB gene cluster region of all VREM isolates represented a single, specific RFLP type. Moreover, in almost all of the isolates, this gene cluster resided within the same wider sequence context which was demonstrated by the results of the DraI/PagI (BspHI) RFLP analysis of the vanB gene cluster locus. It might be postulated that the vancomycin-resistance genes emerged once and were subsequently spread among different E. faecium strains by horizontal DNA transfer. Such transfer, at least in terms of plasmid conjugation, must have been common in the studied population, as was suggested by the observed similarity of REAP patterns produced by all the VREM isolates. However, it is very difficult to reveal the nature of the possible horizontal transmission of vancomycin-resistance genes during the outbreak.

The vanB gene clusters are usually located within active, composite transposons of the Tn1547 type, which may be inserted into either chromosomal or plasmid DNA. Their horizontal spread either may proceed due to conjugative functions of the transposons themselves or may be mediated by plasmids or other transferable elements that contain the Tn1547-like transposons. The vanB locus RFLP analysis carried out with total DNA of the isolates cut with SmaI and separated by PFGE revealed that in almost all the isolates of PFGE types b, c, and d, the vanB gene cluster was located within a DNA fragment of about 90 kb. This could be a plasmid molecule (or part of it) that was disseminated among different strains; however, it cannot be excluded that the conjugative transposon was inserted in their chromosomal DNA in a site-specific manner. The three remaining isolates of PFGE types a and b2 most probably contained two, three, or more copies of the vanB gene cluster that were located either in other plasmids of a large molecular weight (140 to 350 kb) or in chromosomal regions or in both. In the DraI/PagI (BspHI) RFLP analysis of the vanB gene cluster locus, the intense hybridization was obtained with plasmid DNA preparations of the isolates; however, the hybridizing bands could not be identified within their REAP patterns. This suggested that the vanB gene clusters could be present in large and low-copy-number plasmids of poor representation in plasmid preparations, but also, it could not be excluded that the hybridization was due to chromosomal DNA contamination of these. All these data did not allow us to sort out precisely the mechanism of spread of the vanB gene cluster in the studied E. faecium population. It is possible that the cluster was transmitted by both transposon- and plasmid-mediated events and that these were followed by multiplication of transposon copies in at least some of the strains or strain variants.

Analysis was performed of VSEM isolates that were recovered in the same ward of the hospital at the time of the VREM outbreak in order to identify the endemic E. faecium strains which could have acquired VanB resistance genes. Out of 14 VSEM isolates collected from June to December 1999, 6 were found by PFGE to be possibly related to the VREM isolates of PFGE type b, whereas no VSEM isolate produced a PFGE pattern that was similar to those of VREM PFGE types a, c, and d. The five variants of VSEM-specific PFGE type b DNA patterns could also be classified into the two basic similarity groups that were distinguished among PFGE patterns of the type b VREM isolates. It is noteworthy that the SmaI DNA restriction fragments which contained the vanB gene clusters in VREM isolates belonged to those bands that differentiated PFGE patterns specific for VREM and VSEM isolates. These data indicated that the isolates of the PFGE type b, dominating within both VSEM and VREM populations, could represent the endemic E. faecium strain that had been circulating in the hospital environment for a relatively long time. Its spread was accompanied by continuous genetic diversification, and with time the strain produced numerous strain variants along the two main evolutionary lines. The high prevalence of the E. faecium PFGE type b in the single ward of the hospital has created a significant probability of acquisition of vancomycin-resistance genes by its variants, since only these had been introduced. Vancomycin resistance probably emerged after the separation of the two main evolutionary lineages of the strain, and variants belonging to both of these could acquire the resistance genes by at least two different DNA transfer events. Therefore, the predominance of VREM of the PFGE type b isolates among all VREM isolates collected during the outbreak may have been due to both clonal spread and horizontal dissemination of the vanB gene cluster-containing elements. This is one of the few documented cases of identification of an endemic VSE strain that acquired either VanA or VanB resistance determinants in the hospital environment (29, 35; V. S. Albuquerque, C. M. F. Silva, E. A. Marques, L. M. Teixeira, and V. L. C. Merquior, Abstr. 40th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. 1786, 2000; M. M. Kapala, B. M. Willey, F. Arce, G. Large, A. McGeer, and D. E. Low, Abstr. 38th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. H-141, 1998). Our findings together with the previous data support the opinion that the high diversity of VSE strains and strain variants may be an important reason for the observed VRE heterogeneity in a single center (35). Such findings underline the necessity of strict monitoring of infections caused by VSE.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Andrew Hazlewood for critical reading of the manuscript, Patrice Courvalin who kindly provided E. faecalis V583, and Wolfgang Witte for the E. faecium 64/3 strain.

This work was partially financed by a grant from the Polish Committee for Scientific Research (KBN 4P05A 016 19) and the U.S.-Poland Maria Sklodowska-Curie Joint Fund II, MZ/NIH-98-324.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bell J M, Paton J C, Turnidge J. Emergence of vancomycin-resistant enterococci in Australia: phenotypic and genotypic characteristics of isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:2187–2190. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.8.2187-2190.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Birnboim H C, Doly J. A rapid alkaline extraction procedure for screening recombinant plasmid DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1979;7:1513–1523. doi: 10.1093/nar/7.6.1513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boyce J M, Favero M S, Gaynes R P, Goldmann D A, Jarvis W R, Pugliese G, Weinstein R A. Populations at risk and routes of transmission. In: Pugliese G, Weinstein R A, editors. Issues & controversies in prevention and control of VRE. Chicago, Ill: Etna Communications; 1998. pp. 15–16. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boyce J M, Opal S M, Chow J W, Zervos M J, Potter-Bynoe G, Sherman C B, Romulo R L C, Fortna S, Medeiros A A. Outbreak of multidrug-resistant Enterococcus faecium with transferable vanB class vancomycin resistance. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1148–1153. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.5.1148-1153.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carias L L, Rudin S D, Donskey C J, Rice L B. Genetic linkage and cotransfer of a novel, vanB-containing transposon (Tn5382) and a low-affinity penicillin-binding protein 5 gene in a clinical vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium isolate. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:4426–4434. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.17.4426-4434.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chow J W, Kutitza A, Shlaes D M, Green M, Sahm D F, Zervos M J. Clonal spread of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium between patients in three hospitals in two states. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:1609–1611. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.6.1609-1611.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clark N, Cooksey R, Hill B, Swenson J, Tenover F C. Characterization of glycopeptide-resistant enterococci from U.S. hospitals. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:2311–2317. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.11.2311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dahl K H, Skov Simonsen G, Olsvik Ř, Sundsfjord A. Heterogeneity in vanB gene cluster of genetically diverse clinical strains of vancomycin-resistant enterococci. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:1105–1110. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.5.1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Lencastre H, Severina E P, Roberts R B, Kreiswirth B N, Tomasz A. Testing the efficacy of a molecular surveillance network: methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium (VREF) genotypes in six hospitals in the metropolitan New York City area. The BARG Initiative Pilot Study Group. Bacterial Antibiotic Resistance Group. Microb Drug Resist. 1996;2:343–351. doi: 10.1089/mdr.1996.2.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Donskey C J, Schreiber J R, Jacobs M R, Shekar R, Salata R A, Gordon S, Whalen C C, Smith F, Rice L B. A polyclonal outbreak of predominantly VanB vancomycin-resistant enterococci in northeast Ohio. Northeast Ohio Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococcus Surveillance Program. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29:573–579. doi: 10.1086/598636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Evers S, Reynolds P E, Courvalin P. Sequence of the vanB and ddl genes encoding D-alanine:D-lactate and D-alanine:D-alanine ligases in vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis V583. Gene. 1994;140:97–102. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90737-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Facklam R, Collins M D. Identification of Enterococcus species isolated from human infections by a conventional test scheme. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:731–734. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.4.731-734.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fines M, Perichon B, Reynolds P, Sahm D F, Courvalin P. VanE, a new type of acquired glycopeptide resistance in Enterococcus faecalis BM4405. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:2161–2164. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.9.2161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gold H S, Ünal S, Cercenado E, Thauvin-Eliopulos C, Eliopulos G M, Wennerstein C B, Moellering R C., Jr A gene conferring resistance to vancomycin but not teicoplanin in isolates of Enterococcus faecalis and Enterococcus faecium demonstrates homology with vanB, vanA, and vanC genes of enterococci. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:1604–1609. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.8.1604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hryniewicz W, Szczypa K, Bronk M, Samet A, Hellmann A, Trzciński K. First report of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium isolated in Poland. Clin Microbiol Infect. 1999;5:503–505. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.1999.tb00181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kawalec M, Gniadkowski M, Hryniewicz W. Outbreak of vancomycin-resistant enterococci in a hospital in Gdańsk, Poland, due to horizontal transfer of different Tn1546-like transposon variants and clonal spread of several strains. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:3317–3322. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.9.3317-3322.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kawalec M, Gniadkowski M, Zielińska U, Klos W, Hryniewicz W. A vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium strain carrying the vanB2 gene variant in a Polish hospital. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:811–815. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.2.811-815.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klare I, Collatz E, Al-Obeid S, Wagner J, Rodloff A C, Witte W. Glykopeptidresistenz bei Enterococcus faecium aus Besiedlungen und Infectionen von Patienten aus Intensivstationen Berliner Kliniken und einem Transplantationszentrum. ZAC Z Antimikrob Antineoplast Chemother. 1992;10:45–53. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leclercq R, Derlot E, Duval J, Courvalin P. Plasmid-mediated resistance to vancomycin and teicoplanin in Enterococcus faecium. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:157–161. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198807213190307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leclercq R, Dutka-Malen S, Duval J, Courvalin P. Vancomycin resistance gene vanC is specific to Enterococcus gallinarum. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:2005–2008. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.9.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maki D G, Agger W A. Enterococcal bacteremia: clinical features, the risk of endocarditis and management. Medicine. 1988;67:248–269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McGregor K F, Young H-K. Identification and characterization of vanB2 glycopeptide resistance elements in enterococci isolated in Scotland. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:2341–2348. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.9.2341-2348.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moellering R C., Jr Emergence of Enterococcus as a significant pathogen. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;14:1173–1178. doi: 10.1093/clinids/14.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murray B E. The life and times of Enterococcus. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1990;3:46–65. doi: 10.1128/cmr.3.1.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murray B E. Diversity among multidrug-resistant enterococci. Emerg Infect Dis. 1998;4:37–47. doi: 10.3201/eid0401.980106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically. Approved standard M7-A5. Wayne, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Patel R, Uhl J R, Kohner P, Hopkins M K, Steckelberg J M, Kline B, Cockerill F R I. DNA sequence variation within vanA, vanB, vanC-1, and vanC-2/3 genes of clinical Enterococcus isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1988;42:202–205. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.1.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perichon B, Reynolds P E, Courvalin P. VanD-type glycopeptide-resistant Enterococcus faecium BM4339. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:2016–2018. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.9.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Perlada D E, Smulian A G, Cushion M T. Molecular epidemiology and antibiotic susceptibility of enterococci in Cincinnati, Ohio: a prospective citywide survey. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2342–2347. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.9.2342-2347.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Quintiliani R, Jr, Courvalin P. Conjugal transfer of the vancomycin-resistance determinant vanB between enterococci involves the movement of large genetic elements from chromosome to chromosome. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;119:359–364. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb06913.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Quintiliani R, Jr, Courvalin P. Characterization of Tn1547, composite transposon flanked by the IS16 and IS256-like elements, that confers vancomycin resistance in Enterococcus faecalis BM4281. Gene. 1996;172:1–8. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(96)00110-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Quintiliani R, Jr, Evers S, Courvalin P. The vanB gene confers various levels of self-transferable resistance to vancomycin in enterococci. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:1220–1223. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.5.1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sahm D F, Kissinger J, Gilmore M S, Murray B E, Mulder R, Solliday J, Clarke B. In vitro susceptibility studies of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989;33:1588–1591. doi: 10.1128/aac.33.9.1588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Samet A, Bronk M, Hellmann A, Kur J. Isolation and epidemiological study of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium from patients of a haematological unit in Poland. J Hosp Infect. 1999;41:137–143. doi: 10.1016/s0195-6701(99)90051-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Suppola J P, Kolho E, Salmenlinna S, Tarkka E, Vuopio-Varkila J, Vaara M. vanA and vanB incorporate into an endemic ampicillin-resistant vancomycin-sensitive Enterococcus faecium strain: effect on interpretation of clonality. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:3934–3939. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.12.3934-3939.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tenover F C, Arbeit R, Goering V, Mickelsen P, Murray B M, Pershing D, Swaminathan B. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2233–2239. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.9.2233-2239.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thal L, Donabedian S, Robinson-Dunn B, Chow J W, Dembry L, Clewell D B, Alshab D, Zervos M J. Molecular analysis of glycopeptide-resistant Enterococcus faecium isolates collected from Michigan hospitals over a 6-year period. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:3303–3308. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.11.3303-3308.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Uttley A H C, George R C, Naidoo J, Woodford N, Johnson A P, Collins C H, Morrison D, Gilfillan A J, Fitch L E, Heptonstall J. High-level vancomycin-resistant enterococci causing hospital infections. Epidemiol Infect. 1989;103:173–181. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800030478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Werner G, Klare I, Witte W. Arrangement of the vanA gene cluster in enterococci of different ecological origin. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;155:55–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb12685.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Woodford N, Jones B L, Baccus Z, Ludlam H A, Brown D F J. Linkage of vancomycin and high-level gentamicin resistance genes on the same plasmid in a clinical isolate of Enterococcus faecalis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1995;35:179–184. doi: 10.1093/jac/35.1.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]