Abstract

Objectives. To explore barriers to care and characteristics associated with respondent-reported perceived need for opioid use disorder (OUD) treatment and National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH)‒defined OUD treatment gap.

Methods. We performed a cross-sectional study using descriptive and multivariable logistic regression analyses to examine 2015–2019 NSDUH data. We included respondents aged 18 years or older with past-year OUD.

Results. Of 1 987 961 adults, 10.5% reported a perceived OUD treatment need, and 71% had a NSDUH-defined treatment gap. There were significant differences in age distribution, health insurance coverage, and past-year mental illness between those with and without a perceived OUD treatment need. Older adults (aged ≥ 50 years) and non-White adults were more likely to have a treatment gap compared with younger adults (aged 18–49 years) and White adults, respectively.

Conclusions. Fewer than 30% of adults with OUD receive treatment, and only 1 in 10 report a need for treatment, reflecting persistent structural barriers to care and differences in perceived care needs between patients with OUD and the NSDUH-defined treatment gap measure.

Public Health Implications. Public health efforts aimed at broadening access to all forms of OUD treatment and harm reduction should be proactively undertaken. (Am J Public Health. 2022;112(2):284–295. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2021.306577)

More than 2 million US adults have opioid use disorder (OUD), and nearly 90 000 adults are killed by an opioid overdose every year.1,2 Numerous treatment and harm-reduction modalities, including pharmacotherapy, behavioral therapy, safer syringe supplies, and broad access to naloxone, exist for the treatment of OUD and mitigation of harm associated with opioid dependence. Medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD) include buprenorphine, methadone, and naltrexone. Despite the increased availability of MOUD treatment and number of US residents who are insured, evidence suggests a minority (31%) of patients in need of treatment actively seek out or receive it.3,4 Barriers to access include lack of affordability (regardless of insurance status),5 stigma associated with OUD, and lack of access to an OUD treatment program.6

By contrast with the enhanced mobilization for OUD pharmacotherapy and behavioral therapy, considerably fewer resources have been leveraged in support of harm-reduction programs. Furthermore, while our understanding of the etiology of OUD has improved, criminalization of “illicit” opioid use and punitive approaches to such use continue to be meted against low-income communities and communities of color.7 In addition, previous research has found that nearly half of patients with OUD may go into remission without treatment and “recover naturally.”8 This population is often excluded or ignored from formal study that has largely centered OUD treatment paradigms that see pharmacotherapy and behavioral therapy initiation as singular metrics for success.

As a reflection of this epistemic problem, the extant literature on OUD treatment access has often conflated 2 distinct phenomena: (1) treatment gap as defined by providers and (2) perceived treatment need as defined by people with OUD. Using these terms interchangeably has led to inconsistent conclusions and has precluded comparisons across studies and populations.9

To illuminate this discordance and elaborate on the implications for OUD treatment more broadly, we used the most currently available National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) data from 2015 to 2019 to quantify, describe, and contrast the prevalence and sociodemographic and clinical characteristics associated with respondent-reported perceived need for OUD treatment and NSDUH-defined treatment gap, considering the latter 2 measures distinctly.

We focused this analysis on NSDUH because of the pivotal role it plays in shaping federal and state policy priorities regarding OUD. NSDUH is directed by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), and information derived from the annual survey is used to “support prevention and treatment programs, monitor substance use trends, estimate the need for treatment and inform public health policy.”10 Despite many vulnerable populations with high rates of OUD being specifically excluded from study, NSDUH remains central to scaffolding approaches to OUD and opioid use in the United States.

METHODS

We analyzed publicly available NSDUH data from 2015 to 2019 to provide the most current estimates. NSDUH is a cross-sectional household survey of annual self-reported estimates on alcohol, tobacco, and prescription and nonprescription drug use and other health-related domains. The survey is administered online or in person to noninstitutionalized civilians aged 12 years or older living in the United States.11 Because of survey redesign beginning in 2015, NSDUH does not recommend pooling data after 2015 with earlier survey years.

Study Population

All respondents aged 18 years and older classified by NSDUH as having past-year OUD were included in our study. Respondents were classified as having a past-year OUD if they had a past-year prescription pain reliever use disorder or heroin use disorder. We defined past-year prescription pain reliever use disorder (or heroin use disorder) as having past-year dependence or abuse of pain relievers (or heroin).

Study Measures

Using OUD-specific variables (NDTXYRHER, NDTXYRPNR, NDMORTHER, and NDMORTPNR) that define feeling a need, or additional need, for treatment of heroin use and pain reliever use, we created a new variable that designated those with a perceived need for OUD-specific treatment (OUD_need = 1), as having a perceived OUD treatment need.6,12

We categorized past-year treatment gap (i.e., classified as having past-year OUD but not receiving treatment) by using NSDUH variables TXYRNDILL (“needed treatment for illicit drug use”) and TXYRILL (“received treatment at any location for illicit drug use”). We used these measures to create a new variable, tx_gap, with a value of 0 if the individual received treatment for OUD and 1 if the individual needed but did not receive treatment.

Among those with perceived OUD treatment need, NSDUH further asks respondents to report reasons for not receiving treatment or receiving inadequate treatment. Using methods proposed by Novak et al.,6 we collapsed the original list of 14 categories into 6—affordability, treatment access, perceived stigma, treatment not a priority, lack of readiness to stop using, and lack of trust in treatment. We quantified barriers in the overall study sample and further describe barriers by OUD type (prescription OUD only or OUD with heroin use) and by treatment gap status. Respondents can report more than 1 barrier to treatment. In addition, respondents are asked whether they sought treatment or additional treatment in the past year for their OUD treatment need. Further details are included in the Appendix, under “Detailed information regarding treatment barriers” (available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).

Covariates

We included variables in our analysis based on a review of the previous literature6,13,14 and based on an understanding that it is necessary to identify particularly vulnerable subgroups of the population as well as points for clinical and policy interventions.

Sociodemographic and administrative characteristics of interest in our sample were age, sex, highest education level, insurance, and annual income level. We collapsed race/ethnicity into 4 categories because of sample size. We used the variable COUTYP4 to characterize geographic place of residence as “nonmetro” or “metro.”15 In addition, we included survey year in the regression analysis.

Clinical characteristics of interest in our sample included self-reported health and a past-year history of mental health illness. We defined the latter as the presence of serious psychological distress, a major depressive episode, or both in the past year. For self-reported health, we created 2 categories: “good to excellent” (“good,” “very good,” and “excellent”) and “poor to fair” (“poor” and “fair”).

Statistical Analysis

We used weighted proportions and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) to describe the distribution of population characteristics overall and by perceived OUD treatment need and NSDUH-defined treatment gap. We assessed differences in the distribution of characteristics between groups by using the Rao‒Scott χ2 test. We used multivariable logistic regression to assess the association between population characteristics and a treatment gap. Weighted proportions and corresponding standard errors are reported to describe the distribution of barriers to treatment in respondents with perceived OUD treatment need. To account for the complex survey design of NSDUH, we conducted weighted analyses using PROC SURVEYFREQ or PROC SURVEYLOGISTIC in SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC). For the supplementary analysis, we characterized clinical and sociodemographic differences between those with and without a perceived OUD treatment need subset to those with a NSDUH-defined treatment gap. Notably, we ran a multivariable logistic regression model to assess the association between population characteristics and perceived OUD treatment need. However, because of low frequencies in certain predictor variable categories, we were unable to report the results of that analysis.

RESULTS

Of a weighted sample of 1 987 961 (unweighted n = 2183) adults with past-year OUD, 10.5% reported a perceived OUD treatment need (weighted n = 208 793) and 71.1% were defined by NSDUH as having a treatment gap (weighted n = 1 413 870). Table 1 reflects the sample characteristics. The majority of adults were aged 50 years or older (weighted proportion = 54.1%; 95% CI = 51.1%, 57.2%), male (weighted proportion = 58.4%; 95% CI = 55.5%, 61.2%), and non-Hispanic White (weighted proportion = 72.7%; 95% CI = 69.4%, 76.0%). Furthermore, most of the respondents were publicly insured (weighted proportion = 45.6%; 95% CI = 42.5%, 48.7%), lived in a large or small metropolitan area (weighted proportion = 84.7%; 95% CI = 82.6%, 86.9%), reported good to excellent health (weighted proportion = 69.8%; 95% CI = 66.8%, 72.9%), and reported a past-year history of mental illness (weighted proportion = 55.8%; 95% CI = 53.2%, 58.4%). Table A (available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org) provides row estimates within each category of interest. Notably, 11.3% (95% CI = 9.3%, 13.3%) of White and 7.4% (95% CI = 3.2%, 11.6%) of Black adults reported a perceived need for OUD treatment.

TABLE 1—

Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics of US Adults With Past-Year Opioid Use Disorder (OUD), With and Without a Perceived Need for OUD Treatment and With and Without a Treatment Gap: National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) 2015–2019

| Characteristics | Overall OUD (Weighted n = 1 987 961a), Weighted % (95% CI) | Persons With Perceived Need for OUD Treatment (Weighted n = 208 793), Weighted % (95% CI) | Persons Without Perceived Need for OUD Treatment (Weighted n = 1 779 168), Weighted % (95% CI) | Persons With a NSDUH-Defined Treatment Gap (Weighted n = 1 413 870), Weighted % (95% CI) | Persons Without a NSDUH-Defined Treatment Gap (Weighted n = 574 091), Weighted % (95% CI) |

| Age category, yb,c | |||||

| 18–49 | 45.9 (42.8, 48.9) | 58.9 (49.3, 68.4) | 44.4 (41.1, 47.7) | 43.3 (40.0, 46.7) | 52.1 (47.4, 56.9) |

| ≥ 50 | 54.1 (51.1, 57.2) | 41.1 (31.6, 50.7) | 55.6 (52.4, 58.9) | 56.7 (53.3, 60.0) | 47.9 (43.1, 52.6) |

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 41.6 (38.8, 44.5) | 46.6 (38.2, 55.1) | 41.0 (38.0, 44.1) | 41.6 (38.2, 44.9) | 41.7 (37.2, 46.3) |

| Male | 58.4 (55.5, 61.2) | 53.4 (44.9, 61.8) | 59.0 (55.9, 62.0) | 58.4 (55.1, 61.8) | 58.3 (53.7, 62.8) |

| Race/ethnicityc | |||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 72.7 (69.4, 76.0) | 78.3 (71.9, 84.6) | 72.1 (68.4, 75.7) | 70.0 (65.7, 74.4) | 79.3 (75.2, 83.5) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 10.4 (7.7, 13.1) | 7.3 (3.2, 11.4) | 10.8 (7.8, 13.7) | 11.4 (7.8, 15.0) | 7.9 (4.9, 11.0) |

| Hispanic | 11.3 (8.8, 13.9) | 10.2 (4.7, 15.7) | 11.5 (8.7, 14.3) | 12.3 (9.0, 15.5) | 9.0 (5.8, 12.2) |

| Other | 5.6 (4.3, 6.9) | 4.2 (1.7, 6.7) | 5.7 (4.4, 7.1) | 6.3 (4.5, 8.1) | 3.7 (2.2, 5.2) |

| Educationc | |||||

| < high school | 17.9 (15.8, 20.0) | 15.9 (9.9, 21.9) | 18.2 (16.0, 20.4) | 18.0 (15.4, 20.6) | 17.7 (14.3, 21.1) |

| High school graduate | 32.5 (29.5, 35.6) | 37.1 (28.6, 45.6) | 32.0 (28.8, 35.1) | 31.5 (28.0, 34.9) | 35.0 (29.4, 40.7) |

| Some college | 35.2 (31.6, 38.8) | 35.9 (27.8, 44.0) | 35.1 (31.3, 38.9) | 34.2 (30.1, 38.3) | 37.7 (32.4, 43.0) |

| ≥ college graduate | 14.4 (11.7, 17.0) | 11.1 (4.8, 17.4) | 14.7 (11.8, 17.7) | 16.3 (12.7, 19.9) | 9.6 (7.0, 12.1) |

| Household income,c $ | |||||

| < 20 000 | 31.2 (27.9, 34.5) | 33.0 (25.0, 41.1) | 31.0 (27.4, 34.6) | 27.9 (23.8, 32.0) | 39.4 (34.5, 44.2) |

| 20 000‒49 999 | 31.8 (28.8, 34.8) | 35.0 (27.7, 42.3) | 31.4 (28.1, 34.7) | 33.1 (29.5, 36.8) | 28.5 (23.9, 33.0) |

| 50 000‒74 999 | 14.0 (12.0, 16.0) | 10.7 (5.1, 16.4) | 14.4 (12.3, 16.5) | 14.3 (11.9, 16.8) | 13.3 (10.1, 16.5) |

| ≥ 75 000 | 23.0 (19.8, 26.1) | 21.2 (14.6, 27.9) | 23.2 (19.7, 26.6) | 24.6 (21.0, 28.2) | 18.9 (15.0, 22.8) |

| Health insuranceb,c | |||||

| Public insuranced | 45.6 (42.5, 48.7) | 42.7 (35.6, 49.9) | 46.0 (42.5, 49.4) | 41.8 (38.2, 45.5) | 54.9 (49.4, 60.4) |

| Private insurance | 31.7 (29.2, 34.2) | 22.5 (16.1, 28.9) | 32.8 (29.9, 35.7) | 34.4 (31.3, 37.5) | 25.2 (20.8, 29.6) |

| No insurance coverage | 22.7 (19.9, 25.4) | 34.8 (27.7, 41.9) | 21.3 (18.3, 24.2) | 23.8 (20.6, 27.0) | 19.9 (15.0, 24.8) |

| Self-reported healthe | |||||

| Good to excellent | 69.8 (66.8, 72.9) | 68.6 (58.7, 78.5) | 70.0 (66.8, 73.2) | 69.7 (66.2, 73.1) | 70.4 (64.4, 76.4) |

| Poor to fair | 30.1 (27.1, 33.1) | 31.4 (21.5, 41.3) | 30.0 (26.8, 33.1) | 30.3 (26.9, 33.8) | 29.6 (23.6, 35.6) |

| Past-year mental illnessb,c | |||||

| Yes | 55.8 (53.2, 58.4) | 72.3 (64.7, 79.9) | 53.9 (51.2, 56.6) | 53.4 (49.6, 57.2) | 61.9 (56.9, 66.8) |

| No | 44.2 (41.6, 46.8) | 27.7 (20.1, 35.3) | 46.1 (43.4, 48.8) | 46.6 (42.8, 50.4) | 38.1 (33.2, 43.1) |

| Residence | |||||

| Metro | 84.7 (82.6, 86.9) | 83.5 (78.4, 88.5) | 84.9 (82.8, 87.0) | 84.7 (82.1, 87.2) | 84.9 (81.4, 88.4) |

| Nonmetro | 15.3 (13.1, 17.4) | 16.5 (11.5, 21.6) | 15.1 (13.0, 17.2) | 15.3 (12.8, 17.8) | 15.1 (11.6, 18.6) |

Note. CI = confidence interval; OUD = opioid use disorder.

Unweighted no., overall OUD = 2183.

P < .05 from Rao‒Scott χ2 test for comparison between both perceived need groups for each categorical variable.

P < .05 from Rao‒Scott χ2 test for comparison between both treatment gap groups for each categorical variable.

Public insurance was defined as covered by Medicare, Medicaid, Champus, ChampVA, VA, or military insurance.

Columns do not add up to 100% because of missing values reported for self-reported health status.

Table 1 further shows that there were significant differences in the distribution of age, health insurance, and past-year mental health illness between those with and without a perceived OUD treatment need. A majority of those reporting a perceived need were adults aged 18 to 49 years (58.9%; 95% CI = 49.3%, 68.4%), whereas, among those without a perceived need, the majority were adults aged 50 years or older (55.6%; 95% CI = 52.4%, 58.9%). Those with no perceived OUD treatment need had a higher proportion of individuals with private insurance (32.8%; 95% CI = 29.9%, 35.7%), whereas those with a perceived need had a higher proportion of individuals with no insurance coverage (34.8%; 95% CI = 27.7%, 41.9%). Among those with a perceived need, a higher proportion reported a past-year mental health illness (72.3%; 95% CI = 64.7%, 79.9%) compared with the proportion reporting mental health illness in the group without a perceived need (53.9%; 95% CI = 51.2%, 56.6%).

Those with a treatment gap had a higher proportion of respondents with private insurance (34.4%; 95% CI = 31.3%, 37.5%) compared with the proportion reporting private insurance in the group without a treatment gap (25.2%; 95% CI = 20.8%, 29.6%). Table A shows that 68.5% (95% CI = 65.3%, 71.7%) of White adults and 77.9% (95% CI = 69.5%, 86.4%) of Black adults had a treatment gap. More than 65% (65.2%; 95% CI = 61.0%, 69.4%) of those with public insurance, 77.1% (95% CI = 72.9%, 81.3%) with private insurance, and 74.6% (95% CI = 69.0%, 80.3%) without insurance had a treatment gap. Among those with a perceived OUD treatment need, 84.5% had a NSDUH-defined treatment gap, compared with 69.6% of those without a perceived OUD treatment need (Table B, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).

Table 2 presents both the crude and adjusted odds ratios (ORs and AORs, respectively) and 95% CIs of logistic models assessing the association between population characteristics and presence of a NSDUH-defined treatment gap. In the multivariable adjusted analysis, we found that respondents aged 50 years and older had 1.5 times the odds (AOR = 1.5; 95% CI = 1.2, 2.0) of having a treatment gap compared with those aged 18 to 49 years. Hispanic and other race/ethnicity subgroups had higher odds of a treatment gap (AOR = 1.7; 95% CI = 1.0, 2.9 and AOR = 2.3; 95% CI = 1.3, 3.9, respectively) compared with White adults. We also found that Black adults with OUD had higher rates of treatment gap compared with White adults, though this difference was not statistically significant. Characteristics associated with lower odds of a treatment gap included public insurance versus private insurance (AOR = 0.6; 95% CI = 0.4, 0.8) and annual income less than $20 000 versus $50 000 to $74 999 (AOR = 0.7; 95% CI = 0.4, 1.0; P = .04).

TABLE 2—

Sociodemographic and Clinical Factors Associated With the Presence of a Past-Year Treatment Gap in Adults With Opioid Use Disorder: National Survey on Drug Use and Health, United States, 2015–2019

| Characteristics | Treatment Gap Vs No Treatment Gap (Ref) | |

| Crude OR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | |

| Age, y | ||

| 18–49 (Ref) | 1 | 1 |

| ≥ 50 | 1.4 (1.2, 1.8)a | 1.5 (1.2, 2.0)a |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 1.0 (0.8, 1.3) | 0.9 (0.7, 1.1) |

| Female (Ref) | 1 | 1 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic White (Ref) | 1 | 1 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 1.6 (0.9, 2.8) | 1.7 (1.0, 2.9) |

| Hispanic | 1.5 (0.9, 2.5) | 1.7 (1.0, 2.9)a,b |

| Other | 1.9 (1.1, 3.4)a | 2.3 (1.3, 3.9)a |

| Highest education level | ||

| < high school | 1.0 (0.8, 1.4) | 1.1 (0.8, 1.5) |

| ≥ high school (Ref) | 1 | 1 |

| Annual income category, $ | ||

| < 20 000 | 0.7 (0.4, 1.0)a,c | 0.7 (0.4, 1.0)a,c |

| 20 000‒49 999 | 1.1 (0.7, 1.6) | 1.1 (0.7, 1.6) |

| 50 000‒74 999 (Ref) | 1 | 1 |

| ≥ 75 000 | 1.2 (0.9, 1.7) | 1.1 (0.8, 1.6) |

| Self-reported health | ||

| Good to excellent (Ref) | 1 | 1 |

| Poor to fair | 1.0 (0.8, 1.4) | 1.1 (0.8, 1.6) |

| Health insurance | ||

| Public insurance | 0.6 (0.4, 0.8)a | 0.6 (0.4, 0.8)a |

| Private insurance (Ref) | 1 | 1 |

| No insurance coverage | 0.9 (0.6, 1.3) | 1.0 (0.7, 1.5) |

| Past-year mental illness | ||

| Yes | 0.7 (0.5, 1.0)a,c | 0.8 (0.6, 1.0) |

| No (Ref) | 1 | 1 |

| Residence | ||

| Metro (Ref) | 1 | 1 |

| Nonmetro | 1.0 (0.7, 1.4) | 1.2 (0.9, 1.6) |

| Survey year | ||

| 2015 (Ref) | 1 | 1 |

| 2016 | 0.9 (0.7, 1.4) | 1.0 (0.7, 1.5) |

| 2017 | 0.7 (0.5, 1.0)a,c | 0.7 (0.5, 1.1) |

| 2018 | 0.9 (0.6, 1.4) | 0.9 (0.6, 1.4) |

| 2019 | 1.0 (0.6, 1.5) | 1.0 (0.7, 1.6) |

Note. AOR = adjusted odds ratio; OR = odds ratio. AOR > 1 indicates greater odds of treatment gap versus no gap compared with reference group; AOR < 1 indicates lower odds of treatment gap versus no gap compared with reference group; df = 50.

CI does not include the null value.

Before rounding to 1 decimal place, lower limit of CI was above 1.0.

Before rounding to 1 decimal place, upper limit of CI was below 1.0.

Table 3 describes barriers to OUD treatment overall and by OUD type among those who reported a perceived OUD treatment need. Affordability (49.3%) was the most commonly reported barrier to treatment, followed by access (42.1%), lack of readiness to quit (31.9%), and stigma (29.5%). Both the prescription OUD only and OUD with heroin use groups had a similar pattern of reported barriers. Table 3 further shows barriers among those with an OUD treatment need with and without a NSDUH-defined treatment gap, with similar most commonly reported barriers.

TABLE 3—

Barriers to Opioid Use Disorder (OUD) Treatment Overall and by OUD Type Among Individuals With Past-Year OUD and Perceived Treatment Need Who Did Not Receive Treatment at Any Location: National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), United States, 2015‒2019

| Perceived Barrier to OUD Treatment, Weighted Row % (SE) | ||||||

| Affordability | Access | Lack of Readiness | Stigma | Treatment Not a Priority | Lack of Trust in Treatment | |

| Overall OUDa | 49.3 (4.1) | 42.1 (4.0) | 31.9 (3.9) | 29.5 (4.0) | 8.5 (1.8) | . . . |

| Prescription OUD only | 46.7 (4.9) | 38.6 (4.7) | 24.2 (3.9) | 33.2 (5.8) | 9.9 (2.6) | . . . |

| OUD with heroin use | 51.8 (4.1) | 45.3 (4.3) | 39.1 (4.9) | 26.0 (4.1) | 7.1 (1.9) | . . . |

| Barriers among those with a perceived need for OUD treatment and NSDUH-defined treatment gap (weighted n = 176 353): overall OUDb | 53.8 (9.4) | 48.2 (7.2) | 29.5 (8.0) | 24.8 (3.6) | 10.1 (4.5) | . . . |

| Barriers among those with a perceived need for OUD treatment without NSDUH-defined treatment gap (weighted n = 32 440): overall OUDc | 48.5 (4.1) | 40.9 (4.1) | 32.3 (4.0) | 30.4 (4.0) | 8.1 (1.8) | . . . |

Note. Weighted n = 208 793. We do not report results from “lack of trust” barrier because of low count per NSDUH cell suppression rules.

Sample for those with OUD treatment barriers includes only individuals with perceived need for OUD treatment (unweighted n = 252).

Sample for those with OUD treatment barriers includes only individuals with perceived need and NSDUH-defined treatment gap (unweighted n = 205).

Sample for those with OUD treatment barriers includes only individuals with perceived need and without NSDUH-defined treatment gap (unweighted n = 47).

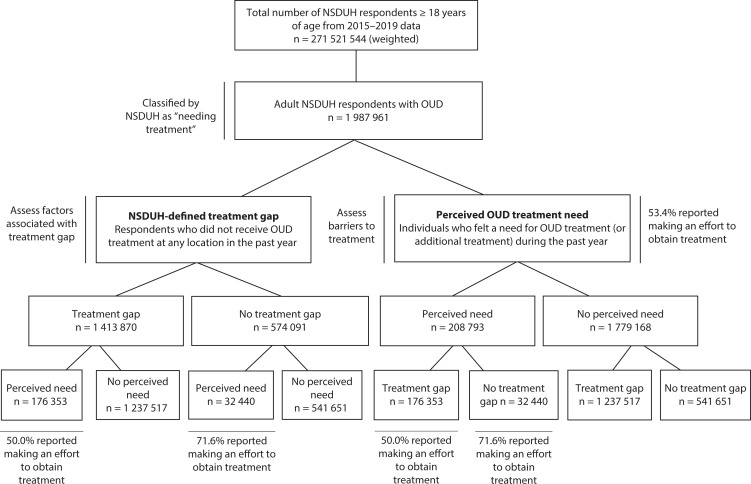

Figure 1 provides an overview of the study sample. Notably, 12.5% of individuals with a treatment gap reported a treatment need, and more than half (53.4%) of the adults with a treatment need reported trying to obtain treatment.

FIGURE 1—

Flow Chart of Study Sample Selection: National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), United States, 2015‒2019

Note. OUD = opioid use disorder. Weighted frequencies reported in figure; total number of NSDUH respondents, 2015–2019, unweighted n = 282 768; adults with past-year OUD, unweighted n = 2183; adults with OUD and past-year treatment gap, unweighted n = 1497; adults with OUD and no past-year treatment gap, unweighted n = 686; adults with OUD and past-year treatment need, unweighted n = 252; adults with OUD and no past-year treatment need, unweighted n = 1931; adults with past-year treatment gap and treatment need, unweighted n = 205; adults with past-year treatment gap and no treatment need, unweighted n = 1292; adults with no past-year treatment gap and with treatment need, unweighted n = 47; adults with no past-year treatment gap and no treatment need, unweighted n = 639; all adults classified as having OUD by NSDUH are also classified as needing treatment.

DISCUSSION

We found that, in a weighted sample of 1 987 961 adults with OUD, only 3 in 10 received treatment as defined by NSDUH in the past year. While nearly three quarters of the sample were classified as having an OUD treatment gap, only 10.5% reported a perceived need for treatment.

There were differences in the distribution of characteristics of persons reporting a need for OUD treatment and those with a NSDUH-defined treatment gap, illuminating both inadequate access to MOUD and the distinctions between the view of treatment vis-à-vis the NSDUH survey and the potentially more expansive view held by persons with OUD. Given the inherent NSDUH study design limitations, it is difficult to draw conclusions about the source and causal relationship between these associations. The NSDUH-based estimate of a treatment gap adheres to a strict treatment definition that ignores natural processes of recovery, economic and carceral consequences to access, and the value of harm-reduction programs. By doing so, more expansive treatment plans, such as those necessitating safe syringe supplies, housing, holistic health care, and other forms of social and economic support, are simply not “counted.” This is despite evidence suggesting that they, too, are effective and critical to improving health outcomes and preventing morbidity and mortality.7 Persons with OUD may thus perceive their care needs as distinct and broader than those offered through pharmacotherapy and behavioral therapy alone, with some not considering resources as “treatment” needs at all but rather as services and social supports necessary for survival.16 While one may propose that the necessary policy intervention to bridge this divide is simply enhanced education and enhanced treatment access, a more critical approach might be to broaden and make more available both treatment and social and economic supports required for improving health outcomes and quality of life. This constellation of resources may include singular or combinations of MOUD, behavioral therapy, and care rooted in principles of harm reduction and health equity.

In addition to highlighting the discordant assessments of care needs, our study updates national estimates of NSDUH-defined OUD treatment access given the multiple policy changes ushered in during the past decade. We found that disparities in OUD treatment by race and class persist with differences underscoring the persistent inequities in care despite purported advancements in insurance attainment as well as treatment availability.

In our analysis, older adults had higher odds of a treatment gap. This finding is consonant with other research13 and can partly be explained by the fact that, among Medicare recipients, the prevalence of OUD has increased by 377% in the past 10 years, outpacing the increased prevalence among younger adults.17,18 However, while the number of Medicare beneficiaries receiving OUD treatment has increased,19 many remain outside the fold of care. Treatment is further complicated by the increasing comorbidities and broader care needs of older adults.18 Until January 2020, Medicare did not reimburse for methadone treatment.20 To enhance coverage, the Substance Use-Disorder Prevention That Promotes Opioid Recovery and Treatment (SUPPORT) for Patients and Communities Act required Medicare to cover OUD treatment, including methadone and behavioral health services at opioid treatment programs (OTPs) beginning in 2020.21 Other research has found that while two thirds of eligible outpatient buprenorphine prescribers for Medicare beneficiaries are family medicine and internal medicine practitioners, they constitute the lowest proportion of active buprenorphine prescribers.22 This demonstrates the unfulfilled capacity for primary care and geriatric care expansion in MOUD prescribing and other forms of care for older adults with OUD.23

We found significantly lower odds of a treatment gap among adults with public insurance compared with those with private insurance. Previous research has also found that adults with Medicaid had more than twice the odds of OUD treatment receipt compared with those with private or other insurance.4,13,24 Despite improvements enabled by the Mental Health Parity Act of 2008 and provisions of the Affordable Care Act (ACA)—including listing substance use disorder treatment as an essential health benefit—challenges to accessing OUD treatment among those privately insured and with no insurance persist.25,26 Recent studies have found that health plans on the ACA Marketplace were more likely to require prior authorization for MOUD than for short-acting prescription opioids.27 Payers also deny SUD treatment claims at higher rates than other medical claims.26 While evidence suggests that Medicaid expansions under the ACA resulted in increased utilization and availability of OUD treatment,28 there continues to be heterogeneity in methadone coverage even in expansion states.29 Other survey-based research has also shown that because of the increasing costs of medications, patients who self-pay are prescribed buprenorphine 12.3 times more than those with private insurance.30 Beneficiaries with private insurance may also elect to self-pay for their MOUD prescriptions, fearing loss of employment if MOUD therapies are adjudicated through their employer-sponsored insurance.31 This is evidenced by our finding that 29.5% of our sample noted “stigma,” related, in part, to the fear that their OUD would have “a negative effect on their job,” as a barrier to treatment.

Our study found that adults from Hispanic and “other” race/ethnicity groups were more likely to have a NSDUH-defined treatment gap compared with White adults but that a lower proportion of Black, Hispanic, and “other” adults had a perceived need for OUD treatment than White adults with OUD. Previous research has shown that non-White adults had lower odds of treatment receipt and that access to OUD treatment is often informed by race.13,29,30,32 We add to this literature by suggesting that potential differences in perceived need by race also reflect different assessment of care needs above and beyond MOUD. Despite federal and regional initiatives to increase the number of eligible prescribers to improve treatment access, the increase in receipt of MOUD has primarily been seen in wealthier and predominantly White counties.33,34 Buprenorphine-providing facilities are more likely to be located in highly segregated, predominantly White counties, and methadone-providing facilities are more likely to be located in highly segregated, predominantly Black and Hispanic/Latino counties.35

Qualitative research has found that persons with OUD prefer buprenorphine to methadone, not only because it is accessible outside of OTPs but also because its use is less “stigmatizing.”36 Furthermore, Black, Brown, and Indigenous communities and low-income communities more broadly are also more likely to be criminalized for their use of opioids under the laws and policies ushered in by the so-called War on Drugs. Nearly 15% of those in prison have an OUD, and Black people are incarcerated at a significantly higher rate than White people for similar drug-related “offenses.”37 These realities, and medical racism more broadly, shape individual perceptions and strategies when engaging with the health care system.4,38 From a critical public health perspective, our findings suggest that access to more flexible, less institutionalized, and less surveilled forms of medical treatment of OUD (unlike methadone, buprenorphine can be picked up at a community pharmacy) should be prioritized, especially in deliberately neglected communities of color.

Although it was not within the scope of this analysis, it is important to acknowledge the role of law enforcement, including that of the Drug Enforcement Agency and the Department of Justice, in shaping punitive responses to OUD. Qualitative research has shown that persons with opioid dependence and OUD treatment needs may be less likely to initiate the care cascade specifically because of fears of law enforcement involvement and coercive involuntary treatment.7,39–41

More than half of the adults with a perceived need for OUD treatment reported making an effort to obtain treatment, underlying the fact that barriers to treatment are informed primarily by structural barriers to care.42–44 Overall, affordability was reported as a barrier by half of those with a perceived need. Even among those with insurance coverage, cost-sharing and frequent pharmacy visits for filling of buprenorphine prescriptions can be cost-prohibitive.45 Factors such as limited methadone coverage within commercial health plans, scarcity of in-network methadone providers, rising costs of pharmaceuticals, and prior authorization requirements also increase patient out-of-pocket costs.7,46

Other barriers commonly reported included access, lack of readiness, and stigma. In our sample, access barriers included difficulty securing childcare, transportation, and treatment openings, or not knowing where to find care or the type of treatment desired. These barriers are interconnected and relate not only to travel times and distances to treatment facilities but also to making frequent visits to the pharmacy or treatment facility47,48 and inequitable availability of buprenorphine at pharmacies. One study found that 1 in 5 pharmacies sampled were either unwilling or unable to fill a buprenorphine prescription entirely, and an additional 7% did not disclose controlled substance availability via phone and required patients to ask in person.49 Importantly, travel burden is also linked to rurality, with patients in rural areas facing greater travel times to access treatment.50 Our study did not find differences in treatment need by geography, but this could in part be because of the limited ability of the COUTYP4 variable in the publicly available NSDUH files to distinguish underresourced rural areas from other geographies.

With respect to availability of treatment, there have been concerted local, state, and federal efforts to enhance treatment access through expanding scope of practice. Under the Drug Addiction Treatment Act of 2000, clinicians must receive an “X-waiver” to provide buprenorphine in outpatient settings. Though insufficient, the recent US Department of Health and Human Services prescribing guidelines exempting all eligible prescribers from federal certification requirements to treat up to 30 patients with buprenorphine was intended to support meeting OUD treatment needs.51,52

Although the number of office-based buprenorphine prescribers has increased, the number of OTPs providing methadone has remained relatively stagnant, partly because of state-level limits on establishing new facilities.53 Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, SAMHSA issued guidance allowing states to request blanket exceptions for patients in OTPs—permitting methadone clinics to provide up to 4 weeks’ supply of medication via telemedicine services instead of requiring burdensome daily visits and dispensing.54 Maintaining these changes and further expanding methadone prescribing in settings beyond OTPs may narrow the gap in MOUD treatment access for those patients that want and seek it.

One third of respondents reported “lack of readiness to stop using” as a barrier to treatment. This finding underscores the importance of prioritizing harm reduction and patient-centered care needs. Relatedly, although prescribing injectable extended-release naltrexone does not require special credentialing by providers, it does require detoxification before starting treatment.55 This abstinence requirement may be a significant barrier to the use of naltrexone, which is known to have lower rates of treatment initiation compared with other MOUD.56,57

Stigma, a complex and multifaceted phenomenon, was also cited as a barrier to OUD treatment by one third of respondents. Often with a racialized and class component, it includes not only how people with OUD perceive themselves but also how they imagine their providers may perceive them.58 Perceived stigma against patients with OUD can lead to decreased likelihood of MOUD prescribing59 and is known to be associated with greater support for punitive policies regarding substance use, denial of services, or reluctance toward MOUD.26,60 Stigma informs the treatment landscape through misconceptions and biases directed at individuals with OUD and at a structural level—toward both OTPs and harm-reduction approaches (the “not-in-my-backyard” phenomenon).58,61 Separation of treatment of addiction from “mainstream” medical issues has further created a feedback loop for stigma, wherein the separation originates from and contributes to stigma.44,61 Normalizing language around OUD as a chronic condition, integrating clinical care with harm reduction, and early, targeted education for key health care providers and staff regularly interacting with persons with OUD is critical.24,62–65

Strengths and Limitations

Our study had several strengths. To address our research goals, we used the most recent data from a source that is used to derive national estimates of OUD treatment needs. We also unpacked the distinct phenomenon of treatment gap and perceived treatment need.9 By quantifying and comparing both NSDUH-defined and patient-defined assessments of treatment need, we were able to illuminate the chasm between the two.

Our study had important limitations. First, NSDUH is based on self-reporting and, thus, is subject to recall bias and underreporting of substance use. Second, NSDUH excludes critical OUD populations (such as those institutionalized with serious mental illness, homeless persons not living in shelters, and incarcerated individuals, including those imprisoned for drug use). Third, NSDUH definitions of treatment are specifically centered around MOUD and behavioral therapy. This definition of treatment is restrictive and ignores the totality of the care needs of patients with OUD that may extend to harm reduction and other critical social supports. Finally, nonprescription fentanyl use is not incorporated in NSDUH variables that capture opioid use disorder.

Conclusions

Our work contributes the most current evidence on OUD treatment needs and illuminates the discordance between NSDUH-defined OUD treatment gaps and patient perceptions of need for OUD “treatment.” By highlighting these differences, we sought to recenter patient agency and person-centered assessments of care and highlight the racial, structural, political, and economic factors that delimit care for low-income communities and communities of color. Furthermore, despite efforts to improve uptake of MOUD treatment, racism, lack of affordability, and stigma all continue to play a role in limiting treatment access. Public health programs and policies for eliminating barriers such as the “X-waiver” and investing in interventions above and beyond MOUD prescribing such as harm reduction should be proactively undertaken. Simultaneously, active disinvestment from carceral and punitive approaches to persons with OUD and persons using opioids should be prioritized to enable fulfillment of their self-described care needs.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was sponsored by faculty support funding to D. M. Qato from the University of Maryland Baltimore and support as an Institute for Clinical and Translational Research (ICTR) KL2 Scholar from the University of Maryland Baltimore Institute for Clinical and Translational Research (1UL1TR003098–01). The KL2 funding source also supported J. Saini as a graduate research assistant to D. M. Qato.

The authors would like to thank the editor and anonymous reviewers for their generous and thoughtful feedback on a previous draft of this article.

Note. The sponsor had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; or in the writing of the article. The submission of the study results was not contingent on the sponsor’s approval or censorship of the manuscript.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

All authors report no relationship or financial interest with any entity that would pose a conflict of interest with the subject matter of this article.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

This was an analysis of publicly available data and was thus exempt from institutional review board review by the University of Maryland, Baltimore.

Footnotes

See also Nesoff et al., p. 199.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/opioids/Medication-Assisted-Treatment-Opioid-Use-Disorder-Study.html

- 2.Baumgartner JC, Radley DC. The drug overdose toll in 2020 and near-term actions for addressing it. Washington, DC: The Commonwealth Fund; 2021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones CM, Campopiano M, Baldwin G, McCance-Katz E. National and state treatment need and capacity for opioid agonist medication-assisted treatment. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(8):e55–e63. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Orgera K, Tolbert J. Key facts about uninsured adults with opioid use disorder. Kaiser Family Foundation. 2016;7 https://www.kff.org/uninsured/issue-brief/key-facts-about-uninsured-adults-with-opioid-use-disorder [Google Scholar]

- 5.Becker WC, Fiellin DA, Merrill JO, et al. Opioid use disorder in the United States: insurance status and treatment access. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;94(1-3):207–213. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Novak P, Feder KA, Ali MM, Chen J. Behavioral health treatment utilization among individuals with co-occurring opioid use disorder and mental illness: evidence from a national survey. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2019;98:47–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2018.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beletsky L, Frederique K, Galea S, et al. https://fxb.harvard.edu/warondrugstoharmreduction2021.

- 8.Kelly JF, Bergman B, Hoeppner BB, Vilsaint C, White WL. Prevalence and pathways of recovery from drug and alcohol problems in the United States population: implications for practice, research, and policy. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;181:162–169. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.09.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mulvaney-Day N, DeAngelo D, Chen C-N, Cook BL, Alegría M. Unmet need for treatment for substance use disorders across race and ethnicity. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;125(suppl 1):S44–S50. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Available https://nsduhweb.rti.org/respweb/homepage.cfm2021.

- 11.National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2019 (NSDUH-2019-DS0001) https://datafiles.samhsa.gov2021.

- 12.Ali MM, Teich JL, Mutter R. Reasons for not seeking substance use disorder treatment: variations by health insurance coverage. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2017;44(1):63–74. doi: 10.1007/s11414-016-9538-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones CM, McCance-Katz EF. Co-occurring substance use and mental disorders among adults with opioid use disorder. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;197:78–82. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Montiel Ishino FA, McNab PR, Gilreath T, Salmeron B, Williams F. A comprehensive multivariate model of biopsychosocial factors associated with opioid misuse and use disorder in a 2017–2018 United States national survey. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1740. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09856-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mack KA. Illicit drug use, illicit drug use disorders, and drug overdose deaths in metropolitan and nonmetropolitan areas—United States. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2017;66(19):1–12. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6619a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ruefli T, Rogers SJ. How do drug users define their progress in harm reduction programs? Qualitative research to develop user-generated outcomes. Harm Reduct J. 2004;1(1):8. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-1-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Allen K.2019. https://www.healthmanagement.com/blog/new-medicare-benefit-opioid-use-disorder-treatment

- 18.Huhn AS, Strain EC, Tompkins DA, Dunn KE. A hidden aspect of the U.S. opioid crisis: rise in first-time treatment admissions for older adults with opioid use disorder. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;193:142–147. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Opioid use decreased in Medicare Part D, while medication-assisted treatment increased. US Department of Health and Human Services Office of Inspector General https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/OEI-02-19-00390.pdf2021.

- 20.Connolly B.2020. https://pew.org/37vDYfH

- 21.Walden GHR.2018. https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-bill/6

- 22.Abraham R, Wilkinson E, Jabbarpour Y, Petterson S, Bazemore A. Characteristics of office-based buprenorphine prescribers for Medicare patients. J Am Board Fam Med. 2020;33(1):9–16. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2020.01.190233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moyo P. Opioid use disorder and its treatment among older adults: an invited commentary. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;27(4):346–348. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2019.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barriers to broader use of medications to treat opioid use disorder. 2019. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK541389

- 25.Wen H, Cummings JR, Hockenberry JM, Gaydos LM, Druss BG. State parity laws and access to treatment for substance use disorder in the United States: implications for federal parity legislation. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(12):1355–1362. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.2169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Madras BK, Ahmad NJ, Wen J, et al. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Huskamp HA, Riedel LE, Barry CL, Busch AB. Coverage of medications that treat opioid use disorder and opioids for pain management in Marketplace plans, 2017. Med Care. 2018;56(6):505–509. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meinhofer A, Witman AE. The role of health insurance on treatment for opioid use disorders: evidence from the Affordable Care Act Medicaid expansion. J Health Econ. 2018;60:177–197. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2018.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pro G, Utter J, Haberstroh S, Baldwin J. Dual mental health diagnoses predict the receipt of medication-assisted opioid treatment: associations moderated by state Medicaid expansion status, race/ethnicity and gender, and year. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;209:107952. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.107952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lagisetty PA, Ross R, Bohnert A, Clay M, Maust DT. Buprenorphine treatment divide by race/ethnicity and payment. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(9):979–981. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.0876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boudreau DM, Lapham G, Johnson EA, et al. Documented opioid use disorder and its treatment in primary care patients across six U.S. health systems. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2020;112S:41–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2020.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hansen H, Roberts SK. Two tiers of biomedicalization: methadone, buprenorphine, and the racial politics of addiction treatment. In: Netherland J, editor. Critical Perspectives on Addiction. Vol 14. Advances in Medical Sociology. Bingley, United Kingdom: Emerald Group Publishing Limited; 2012. pp. 79–102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stein BD, Dick AW, Sorbero M, et al. A population-based examination of trends and disparities in medication treatment for opioid use disorders among Medicaid enrollees. Subst Abus. 2018;39(4):419–425. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2018.1449166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hansen HB, Siegel CE, Case BG, Bertollo DN, DiRocco D, Galanter M. Variation in use of buprenorphine and methadone treatment by racial, ethnic, and income characteristics of residential social areas in New York City. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2013;40(3):367–377. doi: 10.1007/s11414-013-9341-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goedel WC, Shapiro A, Cerdá M, Tsai JW, Hadland SE, Marshall BDL. Association of racial/ethnic segregation with treatment capacity for opioid use disorder in counties in the United States. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(4):e203711. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cioe K, Biondi BE, Easly R, Simard A, Zheng X, Springer SA. A systematic review of patients’ and providers’ perspectives of medications for treatment of opioid use disorder. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2020;119:108146. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2020.108146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Prisoners in 2018. Bureau of Justice Statistics. 2020. Available at https://bjs.ojp.gov/library/publications/prisoners-20182021.

- 38.Leshner AI, Mancher M. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Medications for Opioid Use Disorder Save Lives. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wagner KD, Harding RW, Kelley R, et al. Post-overdose interventions triggered by calling 911: centering the perspectives of people who use drugs (PWUDs) PLoS One. 2019;14(10):e0223823. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0223823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wakeman S, Rich JD.2021. https://www.springer.com/gp/book/9783030808174

- 41.Rosenberg A, Groves AK, Blankenship KM. Comparing Black and White drug offenders: implications for racial disparities in criminal justice and reentry policy and programming. J Drug Issues. 2017;47(1):132–142. doi: 10.1177/0022042616678614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fenton. Health care’s blind side: The overlooked connection between social needs and good health, summary of findings from a survey of America’s physicians. 2011https://sirenetwork.ucsf.edu/tools-resources/resources/health-cares-blind-side-overlooked-connection-between-social-needs-and

- 43.Chatterjee A, Yu EJ, Tishberg L. Exploring opioid use disorder, its impact, and treatment among individuals experiencing homelessness as part of a family. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;188:161–168. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Park JN, Rouhani S, Beletsky L, Vincent L, Saloner B, Sherman SG. Situating the continuum of overdose risk in the social determinants of health: a new conceptual framework. Milbank Q. 2020;98(3):700–746. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.12470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Elitzer J, Tatar M.https://www.chcf.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/PDF-Why-Health-Plans-Should-Go-to-the-MAT.pdf2021.

- 46.Polsky D, Arsenault S, Azocar F. Private coverage of methadone in outpatient treatment programs. Psychiatr Serv. 2020;71(3):303–306. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201900373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Langabeer JR, Stotts AL, Cortez A, Tortolero G, Champagne-Langabeer T. Geographic proximity to buprenorphine treatment providers in the U.S. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;213:108131. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Syed ST, Gerber BS, Sharp LK. Traveling towards disease: transportation barriers to health care access. J Community Health. 2013;38(5):976–993. doi: 10.1007/s10900-013-9681-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kazerouni NJ, Irwin AN, Levander XA, et al. Pharmacy-related buprenorphine access barriers: an audit of pharmacies in counties with a high opioid overdose burden. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021;224:108729. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.108729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lister JJ, Weaver A, Ellis JD, Himle JA, Ledgerwood DM. A systematic review of rural-specific barriers to medication treatment for opioid use disorder in the United States. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2020;46(3):273–288. doi: 10.1080/00952990.2019.1694536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.US Department of Health and Human Services. HHS releases new buprenorphine practice guidelines, expanding access to treatment for opioid use. 2021. https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2021/04/27/hhs-releases-new-buprenorphine-practice-guidelines-expanding-access-to-treatment-for-opioid-use-disorder.html

- 52.Olfson M, Zhang VS, Schoenbaum M, King M. Trends in buprenorphine treatment in the United States, 2009‒2018. JAMA. 2020;323(3):276–277. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.18913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.McBournie A, Duncan A, Connolly E, Rising J.2019. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20190920.981503/full

- 54.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration https://www.shvs.org/covid19-articles/faqs-provision-of-methadone-and-buprenorphine-for-the-treatment-of-opioid-use-disorder-in-the-covid-19-emergency2021.

- 55.The Pew Charitable Trusts. Medications for opioid use disorder https://pew.org/34ixgdT2021.

- 56.Jarvis BP, Holtyn AF, Subramaniam S, et al. Extended-release injectable naltrexone for opioid use disorder: a systematic review. Addiction. 2018;113(7):1188–1209. doi: 10.1111/add.14180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lee JD, Nunes EV Novo P. et al. Comparative effectiveness of extended-release naltrexone versus buprenorphine‒naloxone for opioid relapse prevention (X:BOT): a multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;391(10118):309–318. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32812-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yang LH, Grivel MM, Anderson B, et al. A new brief opioid stigma scale to assess perceived public attitudes and internalized stigma: evidence for construct validity. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2019;99:44–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2019.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stone EM, Kennedy-Hendricks A, Barry CL, Bachhuber MA, McGinty EE. The role of stigma in U.S. primary care physicians’ treatment of opioid use disorder. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021;221:108627. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.108627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Corrigan PW, Nieweglowski K. Stigma and the public health agenda for the opioid crisis in America. Int J Drug Policy. 2018;59:44–49. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2018.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Adams JM, Volkow ND. Ethical imperatives to overcome stigma against people with substance use disorders. AMA J Ethics. 2020;22(1):E702–E708. doi: 10.1001/amajethics.2020.702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bravata K, Cabello-De La Garza A, Earley A, et al. Treating opioid use disorder as a chronic condition. American Academy of Family Physicians. 2021;23 at: https://www.aafp.org/dam/AAFP/documents/patient_care/pain_management/OUD-Chronic-Condition.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 63.McGinty EE, Goldman HH, Pescosolido B, Barry CL. Portraying mental illness and drug addiction as treatable health conditions: effects of a randomized experiment on stigma and discrimination. Soc Sci Med. 2015;126:73–85. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Livingston JD, Adams E, Jordan M, MacMillan Z, Hering R. Primary care physicians’ views about prescribing methadone to treat opioid use disorder. Subst Use Misuse. 2018;53(2):344–353. doi: 10.1080/10826084.2017.1325376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bach P, Hartung D. Leveraging the role of community pharmacists in the prevention, surveillance, and treatment of opioid use disorders. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2019;14(1):30. doi: 10.1186/s13722-019-0158-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]