Abstract

BACKGROUND:

With growth of the use of point of care ultrasound (PoCUS) around the world, some medical schools have incorporated this skill into their undergraduate curricula. However, because of epidemiology of disease and regional differences in approaches to patient care, global application of PoCUS might not be possible. Before creating a PoCUS teaching course, it is critical to perform a needs analysis and recognize the training obstacles.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

A validated online questionnaire was given to final-year medical students at our institution to evaluate their perceptions of the applicability of specific clinical findings, and their own capability to detect these signs clinically and with PoCUS. The skill insufficiency was assessed by deducting the self-reported clinical and ultrasound skill level from the perceived usefulness of each clinical finding.

RESULTS:

The levels of expertise and knowledge in the 229 students who participated were not up to the expected standard. The applicability of detection of abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) (3.9 ± standard deviation [SD] 1.4) was the highest. However, detection of interstitial syndrome (3.0 ± SD 1.1) was perceived as the least applicable. The deficit was highest in the detection of AAA (mean 0.95 ± SD 2.4) and lowest for hepatomegaly (mean 0.57 ± SD 2.3). Although the majority agreed that training of preclinical and clinical medical students would be beneficial, 52 (22.7%) showed no interest, and 60% (n = 136) reported that they did not have the time to develop the skill.

CONCLUSION:

Although medical students in Saudi Arabia claim that PoCUS is an important skill, there are significant gaps in their skill, indicating the need for PoCUS training. However, a number of obstacles must be overcome in the process.

Keywords: Curriculum development, education needs assessment, medical students, point-of-care ultrasound

Introduction

During the 2020 pandemic of coronavirus disease, the role of point of care ultrasound (PoCUS) in the administration of patient care grew significantly.[1] PoCUS is routinely used in clinical practice in a variety of disciplines.[1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10] However, because the concept is novel, few clinicians have any experience with it.

Formal training is essential to guarantee the safe and effective usage of PoCUS.[11,12,13] Evidence, on the other hand, indicates that the training required to achieve proficiency in this valuable skill is minimal.[14,15] Consequently, several international organizations have published position papers promoting the integration of PoCUS into preclinical and clinical undergraduate curricula.[16,17]

Some medical schools have already incorporated PoCUS into their undergraduate curricula.[16,17,18,19,20] However, since medical undergraduate curricula and universities' resources vary greatly, it is impossible to develop a single PoCUS curriculum that would be universally useable.[18] Universities have to, therefore, develop customized ultrasound curricula appropriate to their specific setting. Significant investment is, thus, necessary before PoCUS can be integrated into undergraduate medical education.

The curriculum for undergraduate medical education at our institution in Saudi Arabia has no PoCUS. Because medical education has limited resources, any proposal deemed necessary has to be validated.[13,21] Indeed, a recent study in Saudi Arabia suggested that the internship year was not the best period to begin PoCUS training for physicians.[13] Besides, a needs assessment is essential to establish the necessity and appropriateness of the PoCUS training given to Saudi medical students.[11,22]

The study's main aim was to identify medical students' perceptions on the use of PoCUS and their desire to learn its clinical applications, to measure students' self-reported skill level in PoCUS and physical examination, and to reveal any gaps in the skills. The deficit discovered would define what is required in the PoCUS. The secondary aims of the study were to look into the obstacles to PoCUS training of this cohort and determine whether medical students were learning PoCUS independently.

Materials and Methods

This cross-sectional survey-based research was conducted on medical students at King Saud bin Abdulaziz University for Health Sciences (KSAU-HS) in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The literature showing the significance of PoCUS to medical students and the skillsets needed for the performance of PoCUS were evaluated in order to format the survey.[2,3,4,6,7,9,11,12,13,16,17,18,20,23,24,25] A questionnaire with seven subsections was designed. Face validity was established by two physicians experienced in survey design, medical education, and PoCUS. A pilot survey was conducted to further validate the questionnaire's content, clarity, and length. The responses of five interns were evaluated. Since these five interns agreed on the appropriateness of the material and the clarity of the questions, no changes were made. The survey instrument was then converted to an online questionnaire using Google Forms (Google LLC, USA). Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) vide letter no. IRBC/08219 dated 29/05/2019, and informed written consent was taken from all study participants.

Demographic information and questions on whether participants had chosen their specialty for residency were included in the first subsection on the questionnaire. In the second subsection, participants' use of PoCUS and their training and accreditation were explored. This subsection also included questions on students' willingness to teach themselves PoCUS, and the resources they used to do so. The third subsection focused on the needs assessment by exploring students' attitudes toward learning the clinical applications of PoCUS and whether they perceived that medical students should be able to use PoCUS effectively to diagnose nine specific clinical conditions. The fourth subsection collected the data required to determine the gaps for physical examination skills and PoCUS in relation to the nine conditions included in section 3 and nine other clinical conditions. For each clinical finding, students were asked how relevant it was to their clinical practice. The fifth section assessed the sample's ability to use physical examination and PoCUS (i.e., proficiency) to identify the clinical findings in subsection 4. The sixth segment tested participants' understanding of 16 ultrasound principles, and the seventh the medical students' attitudes toward possible barriers to PoCUS training.

During the academic year from August 30, 2020, to May 6, 2021, 300 medical students were in their final year of undergraduate training (year six) in the College of Medicine at our institution. Of these students, 200 were male and 100 were female. It was projected that the responses of at least 169 medical students (male: 132, female: 80) would be needed in order to achieve a 5% error margin at a 95% confidence level. All year 6 medical students at KSAU-HS were given the opportunity to participate. A link to the online survey was distributed to the medical students via E-mail in January 2021. To increase the RR, further requests to complete the survey were sent via E-mail and social media. Participation was voluntary; no incentives were offered.

The participants' training and accreditation in PoCUS were identified via closed-ended questions. An incremental scale was utilized to quantify the participants' PoCUS practice. Medical students were invited to rate the importance of PoCUS using a Likert scale as well as their self-reported level of skills and knowledge of PoCUS.

The skill deficit for each specified condition was calculated for each participant for both physical examination and PoCUS. Similar approaches for calculating skill deficiencies have been defined.[11,13] Barriers to training were selected from a prepopulated list that enabled several options to be selected.

To analyze the data, standard descriptive statistics were used. Competency, attitudes, knowledge, applicability, and skills were evaluated individually. Replies were grouped according to gender and categorical data were described as frequency and percentage. Based on the 5-point Likert scale, the interval data were given as frequency and mean ± standard deviation (SD). Chi-squared or McNemar tests were used to compare categorical data, while a Student's t-test or analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare interval data. All statistical analyses were carried out using Excel (version 2016, Microsoft, USA).

Results

Of the 300 medical students, 229 participated (mean age 23.8 ± SD 1.7 years), giving a response rate (RR) of 76.3% (male: 134/200, 67%; female: 95/100, 95%). The RR was high and adequate for the achievement of the specified error margin and confidence level. While female participants' RR (95%) was greater than that of the males (67%), their responses were not significantly different. Eighty-one (37.4%) had already decided on the specialty they would apply to for residency. All participants answered all questions and all answers were included in the analyses.

Forty-nine medical students (21.4%; male: 39, female: 10) had received formal training in PoCUS. Twenty-nine (12.7%; male: 21, female: 8) had received informal training. Twenty-seven (11.8%, male: 10, female: 17) reported using online resources (e.g., YouTube, Google LLC, California, USA) to learn PoCUS themselves. Fourteen (6.1%; male: 7, female: 7) had attended free courses on PoCUS outside the medical school. Seven (3.1%, male: 3, female: 4) had paid to attend courses in PoCUS outside the medical school. Three (1.3%) had obtained accreditation in PoCUS and three had obtained accreditation in focused cardiac ultrasound (FoCUS). Only 11 (4.8%) reported using PoCUS for patient assessment. While 217 (94.8%) had never used PoCUS to assess a patient, 129 (56.3%) indicated that they had missed out on PoCUS opportunities because a supervisor was not available.

Tables 1 and 2 summarize the responses to questions on the relevance of learning clinical applications of PoCUS. Most students (176, 76.9%) agreed or strongly agreed with the statement that the lack of access to US after standard working hours (i.e., from 1700 until 0800) could compromise the care of patients. It is, therefore, not surprising that the vast majority (219, 95.6%) agreed or strongly agreed that medical students should learn clinical applications of PoCUS. Of the clinical applications studied, the greatest proportion of the sample agreed or strongly agreed that medical students should be able to diagnose DVT with PoCUS at the bedside (199, 86.9%).

Table 1.

Medical students’ attitudes toward physical examination and point-of-care ultrasound at King Saud Bin Abdulaziz University for Health Sciences (KSAU-HS), Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

| Statement | Likert scale response | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Strongly disagree N (%) | Disagree N (%) | Neutral N (%) | Agree N (%) | Strongly agree N (%) | |

| Physical examination skills are relevant to medical students | 2 (0.9) | 1 (0.4) | 18 (7.9) | 55 (24.0) | 153 (66.8) |

| Learning PoCUS would augment physical exam skills | 2 (0.9) | 21 (9.2) | 56 (24.5) | 78 (34.1) | 72 (31.4) |

| Learning clinical applications of PoCUS would be beneficial | 0 | 1 (0.4) | 9 (3.9) | 99 (43.2) | 120 (52.4) |

| Learning PoCUS is more important than learning physical examination | 70 (30.6) | 88 (38.4) | 44 (19.2) | 10 (4.4) | 17 (7.4) |

| US guidance of procedures would improve patient safety | 0 | 6 (2.6) | 27 (11.8) | 68 (29.7) | 128 (55.9) |

| Lack of access to US services out of hours (whether radiology- or physician-led) may compromise patient care? | 2 (0.9) | 4 (1.7) | 47 (20.5) | 121 (52.8) | 55 (24.0) |

PoCUS: Point-of-care ultrasound, US: Ultrasound

Table 2.

Participants’ attitudes toward specific point-of-care ultrasound competencies for medical students

| Medical students should be competent in the use of PoCUS to | Likert scale response | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Strongly disagree N (%) | Disagree N (%) | Neutral N (%) | Agree N (%) | Strongly agree N (%) | |

| Diagnose pleural effusion | 5 (2.2) | 30 (13.1) | 34 (14.8) | 77 (33.6) | 83 (36.2) |

| Diagnose pneumothorax | 6 (2.6) | 30 (13.1) | 46 (20.1) | 69 (30.1) | 78 (34.1) |

| Diagnose cardiogenic shock | 3 (1.3) | 35 (15.3) | 56 (24.5) | 77 (33.6) | 58 (25.3) |

| Assess volume status (IVC measurement) | 0 | 13 (5.7) | 85 (37.1) | 72 (31.4) | 59 (25.8) |

| Diagnose intra-abdominal hemorrhage | 1 (0.4) | 10 (4.4) | 30 (13.1) | 86 (37.6) | 102 (44.5) |

| Diagnose abdominal aortic aneurysm | 1 (0.4) | 14 (6.1) | 36 (15.7) | 79 (34.5) | 99 (43.2) |

| Diagnose ectopic pregnancy | 3 (1.3) | 8 (3.5) | 22 (9.6) | 93 (40.6) | 103 (45.0) |

| Diagnose deep vein thrombosis | 2 (0.9) | 11 (4.8) | 17 (7.4) | 82 (35.8) | 117 (51.1) |

| Detect thyroid masses | 1 (0.4) | 10 (4.4) | 36 (15.7) | 86 (37.6) | 96 (41.9) |

PoCUS: Point-of-care ultrasound, IVC: Inferior vena cava

For contextualization, 208 (90.8%) agreed or strongly agreed that medical students should learn physical examination skills, and 150 (65.5%) agreed or strongly agreed that learning PoCUS would augment physical examination skills. However, only 27 (11.8%) agreed with the statement that learning PoCUS was more important than learning physical examination skills. The vast majority (158, 69%) disagreed or strongly disagreed with this statement.

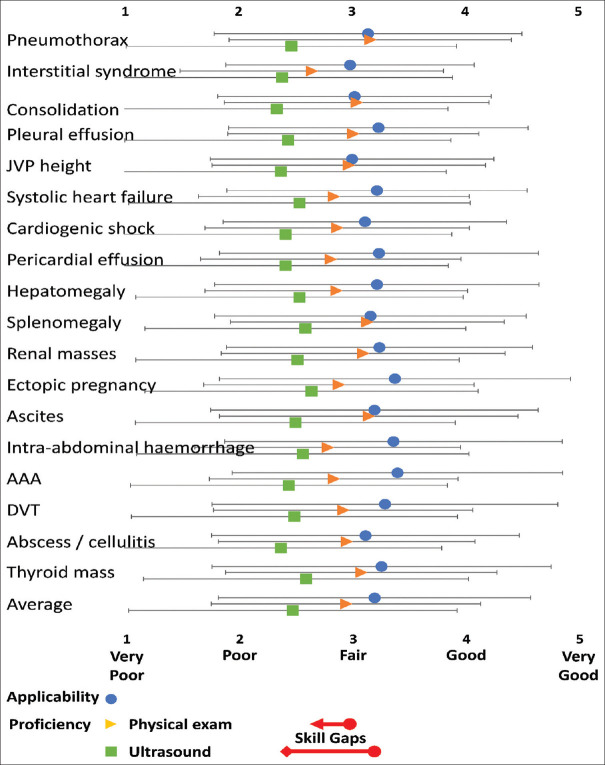

The medical students' perception of the relevance of the detection of 18 clinical conditions is shown in Figure 1. A one-way ANOVA revealed statistically significant differences in the groups' means (F (17,4104) = 1.81, P < 0.02). The overall applicability of PoCUS was fair to good (3.2 ± SD 1.4), with 1809 ratings (44%) of good. The applicability of the detection of abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) (3.9 ± SD 1.4) was the highest. However, detection of interstitial syndrome (3.0 ± SD 1.1) was perceived as the least applicable.

Figure 1.

Medical students' perceptions of the applicability of POCUS and their self-reported proficiency in physical examination and PoCUS. This figure shows medical students' perceptions of the importance of detecting 18 specific clinical conditions and their self-reported proficiency in physical examination and PoCUS to detect these conditions. Applicability and proficiency are rated on a 5-point Likert Scale. Differences between proficiency and applicability [i.e., the skill gap, Figure 3] for each clinical condition were statistically significant for both physical examination and PoCUS (P < 0.00001). The red arrows indicate the overall skill gaps (i.e., the difference between the average applicability and self-reported proficiency in physical examination and PoCUS for all clinical skills). Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. AAA: Abdominal aortic aneurysm, DVT: Deep vein thrombosis, JVP: Jugular venous pressure

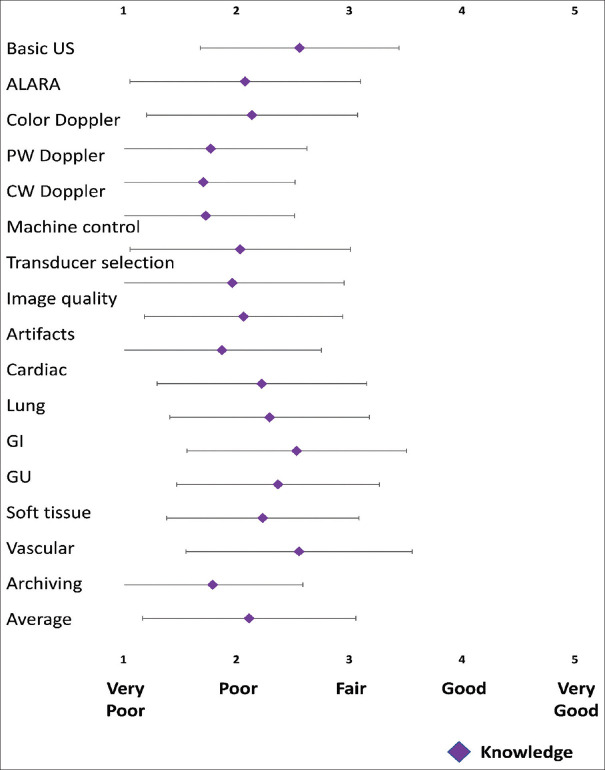

Medical students were most knowledgeable about the primary theoretical and practical principles required to perform PoCUS (i.e., the fundamental principles of ultrasound mean 2.6 ± SD 0.9). The overall self-reported PoCUS knowledge, however, was poor [Figure 2]. Doppler imaging and archiving had the lowest levels of knowledge reported (mean 1.8 ± SD 0.8).

Figure 2.

Medical students' knowledge of the principles of ultrasound required to use PoCUS. This figure shows medical students' knowledge of the principles of ultrasound. Knowledge was self-reported on a 5-point Likert Scale. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. ALARA: As low as reasonably achievable, CW: Continuous wave, GI: Gastrointestinal, GU: Genitourinary, PW: Pulsed wave, US: Ultrasound

Figure 1 shows participants' self-reported level of skills in physical examination and PoCUS to detect 18 specified clinical conditions. While they reported that their physical examination skills were fair, their PoCUS proficiency was poor. The self-reported proficiency for the detection of consolidation (mean 2.3 ± SD 1.5) was the lowest. However, the average self-reported skills in physical examination and PoCUS were considerably lower (P < 0.01) than the average perceived applicability of detecting the specified clinical conditions [Figure 1]. The deficiency was highest in the detection of AAA (mean 0.95 ± SD 2.4) and lowest for hepatomegaly (mean 0.57 ± SD 2.3).

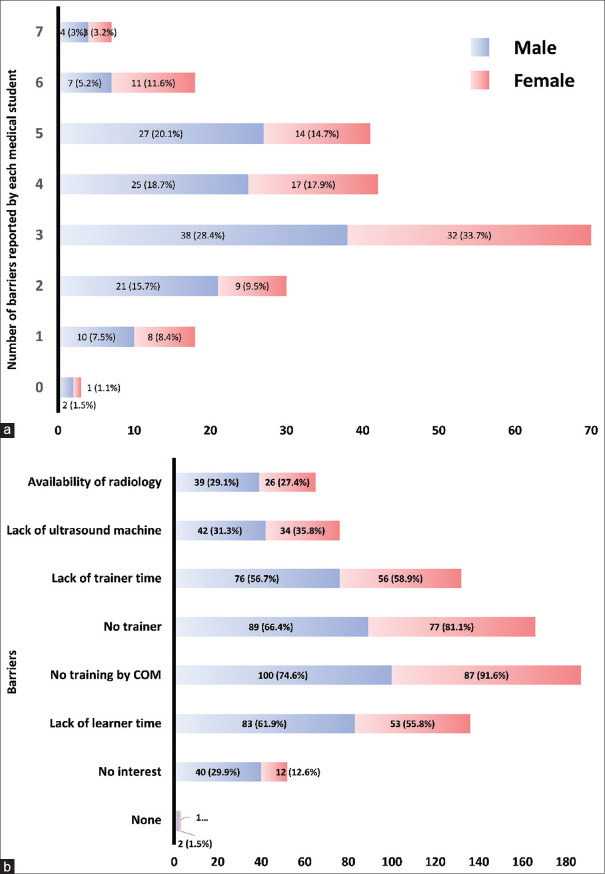

Figure 3 shows the obstacles related to PoCUS training. The most commonly cited barriers were the lack of training by the College of Medicine (187, 81.7%; female: 87) and lack of trainers (166, 72.5%; female: 77) and lack of trainer time (132, 57.6%; female: 53). The lack of interest was common (52, 22.7%; female: 12). It is also noteworthy that 136 (59.4%; male: 83, female: 53) reported that medical students had little time for PoCUS training.

Figure 3.

Barriers to learning PoCUS in medical school. (a) The number of barriers indicated by each student. Data are presented as frequency. (b) Specific barriers to training indicated by the sample of medical students. Data are presented as frequency and percentage of gender strata. COM: College of medicine

Discussion

Traditional physical examination contributes at most 20% to the diagnostic process.[26] Since many clinical signs have poor reliability and little validity,[27] several medical specialties use PoCUS-enhanced clinical assessments to obtain immediate answers to specific questions.[2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,28,29]

Therefore, medical schools worldwide have already introduced PoCUS into the curricula for their medical undergraduates. Despite the limited usefulness of physical examination,[26,27] only 12% agreed or strongly agreed with the statement that learning PoCUS was more important than learning physical examination skills. Exploration of students' attitudes toward PoCUS is of much interest.

The instrument used in the present study sought participants' perceptions of the applicability of PoCUS for the detection of select pathologies. Most of the sample thought that medical students in Saudi Arabia should be competent in the use of PoCUS for the diagnosis of several specific medical conditions, particularly intra-abdominal hemorrhage, AAA, and ectopic pregnancy. This possibly reflects their perception of the severity of the consequences of missing these diagnoses on patient outcomes, and the difficulty of detecting these conditions without imaging.

While the current study was conducted shortly after the first wave of the 2020 pandemic of coronavirus disease, the use of PoCUS to diagnose interstitial syndrome was considered least relevant. The point should be made that ultrasound expertise and competence of the participants to perform PoCUS were both deficient. Thus, participants were unlikely to be aware of the latest research on the role of lung ultrasound in the assessment of coronavirus disease 2019.[30] It is, therefore, crucial for subject experts to be involved in curriculum development.

The participants' level of PoCUS skills was low. Specific skill deficiencies are defined by the discrepancy between perceived usefulness and ability to perform the skills.[11,13] Educational interventions can help to correct these flaws.[11,12,14,15] Consequently, measuring the gaps would help guide the allocation of the limited resources for medical education.

The applicability of the diagnosis of each of the 18 specific clinical conditions was higher than the level of skills in both physical examination and PoCUS. However, the deficit was greater for PoCUS. This finding highlights major PoCUS skill deficits in medical undergraduates. Only by creating and implementing a PoCUS training program at the College of Medicine will this deficiency be addressed.

While there are suggestions, competencies, and curricula for undergraduate training in PoCUS,[16,17] they must be tailored to the specific needs of each context using essential guidelines for the process:[21,31]

The curriculum should be simple to teach and learn.[21,31] Skills must be examined to guarantee competency and progress across each level of proficiency in the learning process

The use of PoCUS requires clear indications (e.g., to accomplish a distinct objective, such as determining whether a pleural effusion is the cause of opacification on a chest X-ray)

It is necessary to establish the scope of practice and institutional privileges.[21,31] Students need to be taught their limitations.[21,31] When performing PoCUS, it is critical to know when help from a professional (such as a radiologist) is necessary.

The implementation of the curriculum is the next challenge. Every institution providing the training, needs to have PoCUS champions[21,31] to provide regular didactic sessions, ensure availability of adequate equipment, and most significantly, proffer hands-on training.[21,31]

To deliver this, faculty with sufficient theoretical, clinical, and practical knowledge and capabilities must be enlisted.[21,31] Faculty members should be well-trained, institutionally qualified, and, preferably, accredited.[21,31] These individuals must dedicate themselves to training and evaluating students. Regrettably, our findings indicate that students were unable to complete PoCUS because of the lack of supervisors. Prioritizing institutional support for faculty training and infrastructure for continuous quality assurance activities, including a secure system for picture archiving, is essential.[21,32] This will necessitate the assistance of fully certified sonographers and radiologists in the radiology department.

Implementing a curriculum clearly necessitates significant resources and competent organization. To make this easier and ensure that crucial components of medical education are not overlooked, quality indicators for medical education must be employed.[24] The implementation of this approach in Saudi Arabia might potentially be influenced by prior experience with PoCUS in other nations. Indeed, Saudi medical students' perceptions of the applicability of PoCUS were similar to those reported by American students, interns, and residents.[20] Thus, international standardization of undergraduate PoCUS training may be feasible.

The most commonly documented barriers were the lack of training by the College of Medicine and lack of trainers and trainer time. Curriculum development and enhanced trainer availability can help overcome these obstacles.[13] Ultrasound machines should also be made more accessible. Inexpensive, ultraportable devices are now widely accessible.[33] Whatever the case may be, the financial capital required to overcome these obstacles will be significant.

A noteworthy challenge is that over 20% were not interested in learning PoCUS and 60% reported that they did not have time to learn. Although the prospect of learning a new skill could be formidable, those interested in learning PoCUS quickly become skilled with very little training.[14,15]

Medical students must prioritize a variety of competing demands on their time. However, they have to set aside time to get the clinical knowledge and skills required to offer high-quality care. Almost 12% were sufficiently interested to try to learn PoCUS on their own. Starting undergraduates on PoCUS training in colleges of medicine would be optimal. However, previous evidence from Saudi Arabia suggests that this training is best given in residency and fellowship programs for now. At least until undergraduate training has been established.[13]

The survey was performed on final-year medical students in the middle of the scholastic year toward the end of the students' 6-year training program. This means that the findings and recommendations could be applied to interns, at least, at the start of their internships.

The study has some drawbacks, even though the RR exceeded the required accuracy. Data obtained from self-reported expertise have many possible sources of bias.[34]

The findings of the present study may be restricted in their generalizability. It was conducted on final year medical students in one college of medicine in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. However, KSAU-HS has approximately 300 medical students in each year and the curriculum allows students to take elective rotations. Medical students can opt to do their elective placements in any medical center in the country. Thus, the present sample may provide some insight into the perceptions of medical students training in other places in Saudi Arabia.

Our findings could be relevant to institutions wanting to develop PoCUS training for medical students in a safe and effective manner. The findings showed that medical students training in Saudi Arabia perceive that PoCUS skills are applicable to their current practice. However, since no PoCUS training is offered in undergraduate medical education at our institution, participants' knowledge and skills in PoCUS were deficient and revealed a significant PoCUS skill gap. A small number of medical students were uninterested in learning about PoCUS. A few students thought that they did not have enough time for PoCUS training.

Conclusion

Despite the fact that medical students in Saudi Arabia believe PoCUS is a useful important skill, they are not given any training in this area. Their proficiency is limited, and there is a considerable skill gap. Various barriers to need to be overcome to allow integration of PoCUS into medical school curricula.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Rajendram R, Hussain A, Mahmood N, Kharal M. Feasibility of using a handheld ultrasound device to detect and characterize shunt and deep vein thrombosis in patients with COVID-19: An observational study. Ultrasound J. 2020;12:49. doi: 10.1186/s13089-020-00197-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singh Y, Tissot C, Fraga MV, Yousef N, Cortes RG, Lopez J, et al. International evidence-based guidelines on Point of Care Ultrasound (POCUS) for critically ill neonates and children issued by the POCUS Working Group of the European Society of Paediatric and Neonatal Intensive Care (ESPNIC) Crit Care. 2020;24:65. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-2787-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Conlon TW, Nishisaki A, Singh Y, Bhombal S, De Luca D, Kessler DO, et al. Moving beyond the stethoscope: Diagnostic point-of-care ultrasound in pediatric practice. Pediatrics. 2019;144:e20191402. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Longjohn M, Wan J, Joshi V, Pershad J. Point-of-care echocardiography by pediatric emergency physicians. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2011;27:693–6. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e318226c7c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pereda MA, Chavez MA, Hooper-Miele CC, Gilman RH, Steinhoff MC, Ellington LE, et al. Lung ultrasound for the diagnosis of pneumonia in children: A meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2015;135:714–22. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-2833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marin JR, Dean AJ, Bilker WB, Panebianco NL, Brown NJ, Alpern ER. Emergency ultrasound-assisted examination of skin and soft tissue infections in the pediatric emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2013;20:545–53. doi: 10.1111/acem.12148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pomero F, Dentali F, Borretta V, Bonzini M, Melchio R, Douketis JD, et al. Accuracy of emergency physician-performed ultrasonography in the diagnosis of deep-vein thrombosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Thromb Haemost. 2013;109:137–45. doi: 10.1160/TH12-07-0473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koratala A, Bhattacharya D, Kazory A. Point of care renal ultrasonography for the busy nephrologist: A pictorial review. World J Nephrol. 2019;8:44–58. doi: 10.5527/wjn.v8.i3.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olson AP, Trappey B, Wagner M, Newman M, Nixon LJ, Schnobrich D. Point-of-care ultrasonography improves the diagnosis of splenomegaly in hospitalized patients. Crit Ultrasound J. 2015;7:13. doi: 10.1186/s13089-015-0030-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sibley S, Roth N, Scott C, Rang L, White H, Sivilotti ML, et al. Point-of-care ultrasound for the detection of hydronephrosis in emergency department patients with suspected renal colic. Ultrasound J. 2020;12:31. doi: 10.1186/s13089-020-00178-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Watson K, Lam A, Arishenkoff S, Halman S, Gibson NE, Yu J, et al. Point of care ultrasound training for internal medicine: A Canadian multi-centre learner needs assessment study. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18:217. doi: 10.1186/s12909-018-1326-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beaulieu Y, Laprise R, Drolet P, Thivierge RL, Serri K, Albert M, et al. Bedside ultrasound training using web-based e-learning and simulation early in the curriculum of residents. Crit Ultrasound J. 2015;7:1. doi: 10.1186/s13089-014-0018-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jarwan W, Alshamrani AA, Alghamdi A, Mahmood N, Kharal YM, Rajendram R, et al. Point-of-care ultrasound training: An assessment of interns' needs and barriers to training. Cureus. 2020;12:e11209. doi: 10.7759/cureus.11209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Caronia J, Panagopoulos G, Devita M, Tofighi B, Mahdavi R, Levin B, et al. Focused renal sonography performed and interpreted by internal medicine residents. J Ultrasound Med. 2013;32:2007–12. doi: 10.7863/ultra.32.11.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arora S, Cheung AC, Tarique U, Agarwal A, Firdouse M, Ailon J. First-year medical students use of ultrasound or physical examination to diagnose hepatomegaly and ascites: A randomized controlled trial. J Ultrasound. 2017;20:199–204. doi: 10.1007/s40477-017-0261-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cantisani V, Dietrich CF, Badea R, Dudea S, Prosch H, Cerezo E, et al. EFSUMB statement on medical student education in ultrasound [long version] Ultrasound Int Open. 2016;2:E2–7. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1569413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dietrich CF, Hoffmann B, Abramowicz J, Badea R, Braden B, Cantisani V, et al. Medical student ultrasound education: A WFUMB position paper, Part I. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2019;45:271–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2018.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prosch H, Radzina M, Dietrich CF, Nielsen MB, Baumann S, Ewertsen C, et al. Ultrasound curricula of student education in Europe: Summary of the experience. Ultrasound Int Open. 2020;6:E25–33. doi: 10.1055/a-1183-3009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Siegel-Richman Y, Kendall J. Establishing an ultrasound curriculum in undergraduate medical education: How much time does it take? J Ultrasound Med. 2018;37:569–76. doi: 10.1002/jum.14371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stone-McLean J, Metcalfe B, Sheppard G, Murphy J, Black H, McCarthy H, et al. Developing an undergraduate ultrasound curriculum: A needs assessment. Cureus. 2017;9:e1720. doi: 10.7759/cureus.1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Souleymane M, Rajendram R, Mahmood N, Ghazi AM, Kharal YM, Hussain A. A survey demonstrating that the procedural experience of residents in internal medicine, critical care and emergency medicine is poor: Training in ultrasound is required to rectify this. Ultrasound J. 2021;13:20. doi: 10.1186/s13089-021-00221-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kern D, Thomas P, Hughes M. Baltimore, Maryland, USA: The Johns Hopkins University Press; 2009. Curriculum Development for Medical Education: A Six-Step Approach. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smallwood N, Matsa R, Lawrenson P, Messenger J, Walden A. A UK wide survey on attitudes to point of care ultrasound training amongst clinicians working on the Acute Medical Unit Foundation Trust. Acute Med. 2016;14:158–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ambasta A, Balan M, Mayette M, Goffi A, Mulvagh S, Buchanan B, et al. Education indicators for internal medicine point-of-care ultrasound: A consensus report from the Canadian Internal Medicine Ultrasound (CIMUS) Group. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34:2123–9. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-05124-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alber KF, Dachsel M, Gilmore A, Lawrenson P, Matsa R, Smallwood N, et al. Curriculum mapping for Focused Acute Medicine Ultrasound (FAMUS) Acute Med. 2018;17:168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peterson MC, Holbrook JH, Von Hales D, Smith NL, Staker LV. Contributions of the history, physical examination, and laboratory investigation in making medical diagnoses. West J Med. 1992;156:163–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Benbassat J, Baumal R. Narrative review: Should teaching of the respiratory physical examination be restricted only to signs with proven reliability and validity? J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:865–72. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1327-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Su E, Dalesio N, Pustavoitau A. Point-of-care ultrasound in pediatric anesthesiology and critical care medicine. Can J Anesth. 2018;65:485–98. doi: 10.1007/s12630-018-1066-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen L, Kim Y, Santucci KA. Use of ultrasound measurement of the inferior vena cava diameter as an objective tool in the assessment of children with clinical dehydration. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14:841–5. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2007.06.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guitart C, Suárez R, Girona M, Bobillo-Perez S, Hernández L, Balaguer M, et al. Lung ultrasound findings in pediatric patients with COVID-19. Eur J Pediatr. 2021;180:1117–23. doi: 10.1007/s00431-020-03839-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hussain A, Ma IW. Internal medicine point of care ultrasound in the 21st century: A “FoCUS” on the Middle East. J Saudi Heart Assoc. 2020;32:479–82. doi: 10.37616/2212-5043.1225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wong J, Montague S, Wallace P, Negishi K, Liteplo A, Ringrose J, et al. Barriers to learning and using point-of-care ultrasound: A survey of practicing internists in six North American institutions. Ultrasound J. 2020;12:19. doi: 10.1186/s13089-020-00167-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nielsen MB, Cantisani V, Sidhu PS, Badea R, Batko T, Carlsen J, et al. The use of handheld ultrasound devices – An EFSUMB position paper. Ultraschall Med. 2019;40:30–9. doi: 10.1055/a-0783-2303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Davis DA, Mazmanian PE, Fordis M, Van Harrison R, Thorpe KE, Perrier L. Accuracy of physician self-assessment compared with observed measures of competence: A systematic review. JAMA. 2006;296:1094–102. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.9.1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]