Abstract

Determinants of Post-Acute Sequelae of COVID-19 are not known. Here we show that 83.3% of patients with viral RNA in blood (RNAemia) at presentation were symptomatic in the post-acute phase. RNAemia at presentation successfully predicted PASC, independent of patient demographics, worst disease severity, and length of symptoms.

Keywords: Long COVID, PASC, RNAemia, SARS-CoV-2

The determinants of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) severity and extrapulmonary complications have now been well studied, and RNAemia (viral RNA in blood) has emerged as an important factor [1, 2]. Much less is known about the determinants of postacute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC), the persistence or development of new symptoms after the acute phase of infection, recently reported to affect as many as 87.4% of COVID-19 patients [3, 4], primarily those with with moderate or worse severity [5, 6]. Recent evidence has suggested persistent clotting protein pathology with elevated levels of antiplasmin [7] and nonclassical monocytes [8] in patients with PASC. Discovery of SARS-CoV-2 S1 protein in these nonclassical monocytes and fragmented SARS-CoV-2 RNA in peripheral blood mononuclear cells in a PASC patient 15 months postinfection further exhibited the persistence of viral particles [8]. Given the importance of RNAemia in disease severity and its persistence in the blood, we describe the relationship between RNAemia at presentation and postacute symptoms at least 4 weeks after symptom onset.

We studied the clinical trajectories of 127 patients enrolled in the institutional review board–approved (eP-55650) Stanford Hospital Emergency Department (ED) COVID-19 Biobank between April and November 2020 with completed follow-ups. We assessed symptoms and severity (based on a modified World Health Organization scale) [1] on the date of enrollment (median = 4, range = 0–14 days after symptom onset) and at least 4 weeks after symptom onset (median = 35, range = 28–75 days) as per the current Centers for Disease Control and Prevention definition of PASC (https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/clinical-care/post-covid-conditions.html).

We measured SARS-CoV-2 RNAemia at the time of enrollment using the definitions of our earlier study [1]. We compared the proportions of initially RNAemic and non-RNAemic patients with persistent or new symptoms in the postacute phase using a 2-sample chi-square test with continuity correction. We estimated the association between RNAemia at enrollment and PASC at follow-up in a logistic model controlling for worst severity within 30 days of enrollment, patient demographics (age and gender), presence of any symptom at enrollment (anxiety, dizziness, fatigue, hair loss, palpitations, rash, insomnia, chest pain, chills, cough, decrease in sense of taste, fever, nausea/vomiting/diarrhea, headache, loss of smell, myalgia, new confusion, shortness of breath), and durations of symptoms. We also compared the median number of PASC symptoms for RNAemic and non-RNAemic patients using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test with continuity correction. We performed all analyses in R (version 4.0.3).

Forty-eight percent (61/127) of patients were women, and the median age (interquartile range [IQR]) was 48 (34–60) years. At enrollment, 26.8% (34/127) of patients had mild disease severity, 66.9% (85/127) moderate, and 6.3% (8/127) severe. Patients had a median (IQR) of 5 (3–8) symptoms: 74.8% (95/127) had a cough, 66.9% (85/127) had shortness of breath, and 66.9% (85/127) had fever. In the postacute phase, 51.2% (65/127) had 1 or more new (23.6% [30/127]) or persistent (38.6% [49/127]) symptoms, of which the most common were cough, shortness of breath, and loss of smell (Table 1). Point eight percent (1/127) of patients developed anxiety and hair loss that were not present at enrollment.

Table 1.

Progression of COVID-19 Symptoms

| Symptom | On Enrollment, % (No.) | Persistent at Follow-up, % (No.) | New at Follow-up, % (No.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular | |||

| Chest pain | 34.6 (44/127) | 11.4 (5/44) | 0.8 (1/122) |

| Palpitations | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1.6 (2/127) |

| Dermatologic | |||

| Rash | 1.6 (2/127) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Hair loss | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.8 (1/127) |

| Gastrointestinal | |||

| Nausea/vomiting/diarrhea | 44.9 (57/127) | 7.0 (4/57) | 0 (0) |

| Constitutional | |||

| Fever | 66.9 (85/127) | 1.2 (1/85) | 0 (0) |

| Chills | 35.4 (45/127) | 2.2 (1/45) | 0 (0) |

| Myalgia | 43.3 (55/127) | 16.4 (9/55) | 3.4 (4/118) |

| Fatigue | 38.6 (49/127) | 12.2 (6/49) | 8.3 (10/121) |

| Neuropsychiatric | |||

| Loss of taste | 39.4 (50/127) | 16.0 (8/50) | 0 (0) |

| Loss of smell | 30.7 (39/127) | 17.9 (7/39) | 0 (0) |

| Confusion | 3.1 (4/127) | 0 (0) | 3.1 (4/127) |

| Headache | 24.4 (31/127) | 3.2 (1/31) | 4.8 (6/126) |

| Dizziness | 5.5 (7/127) | 14.3 (1/7) | 3.3 (4/120) |

| Insomnia | 0.8 (1/127) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Anxiety | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.8 (1/127) |

| Respiratory | |||

| Cough | 74.8 (95/127) | 26.3 (25/95) | 4.9 (5/102) |

| Shortness of breath | 66.9 (85/127) | 22.4 (19/85) | 0.9 (1/108) |

Abbreviation: COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019.

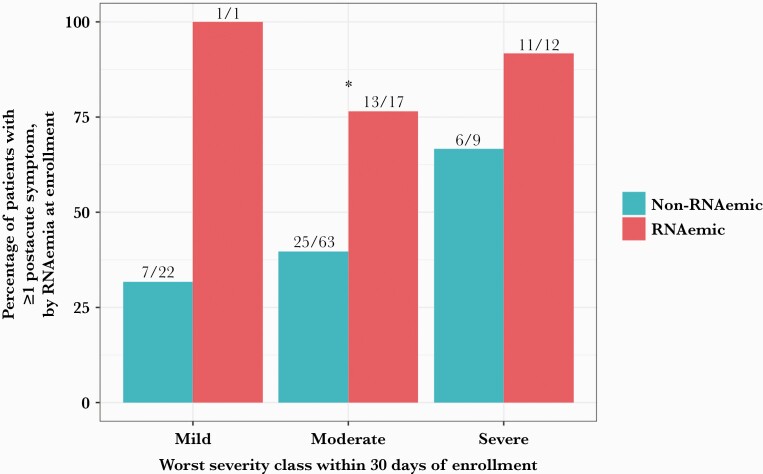

Eighty-three point three percent (25/30) of initially RNAemic patients were symptomatic in the postacute phase, compared with 41.2% (40/97) of non-RNAemic patients (difference, 42.1%; 95% CI, 23.4%–60.8%; P = .0001322). RNAemic patients had a median of 1 symptom in the postacute phase compared with 0 in non-RNAemic patients (P = .000745, Wilcoxon rank-sum test). RNAemia at presentation predicted PASC, conditional on patient demographics and worst disease severity (odds ratio, 5.75; 95% CI, 1.99–19.45; P = .00223) (Supplementary Data). The association was strongest for patients with moderate disease within 30 days of symptom onset (Figure 1), with 76.5% (13/17) of initially RNAemic patients symptomatic in the postacute phase, compared with 39.7% (25/63) of non-RNAemic patients (difference, 36.8%; 95% CI, 9.5%–65.0%; P = .01544). This difference was due almost entirely to persistent or new respiratory symptoms (difference in proportions, 36.1%; 95% CI, 14.4%–57.7%; P = .0003601).

Figure 1.

Rate of postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection, by RNAemia and worst clinical severity. Overall, 83.3% (25/30) of initially RNAemic patients had 1 or more postacute symptoms at follow-up, compared with 41.2% (40/97) of non-RNAemic patients (difference, 42.1%; 95% CI, 23.4%–60.8%; P = .0001322). Conditional on worst severity within 30 days of enrollment (mild = discharged from ED [n = 23]; moderate = hospitalized, requiring no more than oxygen by nasal cannula [n = 80]; severe = hospitalized, requiring high-flow nasal cannula or mechanical ventilation [n = 21]), RNAemia on presentation was associated with significantly higher rates of PASC for moderate severity (difference, 36.8%; 95% CI, 9.5%–64.0%; P = .01544). ∗P < .05. Abbreviations: COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; ED, emergency department; PASC, postacute sequelae of COVID-19; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

To our knowledge, this study describes the first reported association between SARS-CoV-2 RNAemia and PASC. RNAemia at presentation was associated with new or persistent symptoms at least 28 days after symptom onset independent of initial patient severity, and the association was strongest among patients with moderately severe clinical presentations requiring hospital admission. This finding adds to the growing literature on SARS-CoV-2 RNAemia’s role in disease severity and extrapulmonary complications in the acute phase of illness, as well as the association between hospitalization and PASC [1, 2, 5, 6]. The incidence of PASC was lower in this single-center study than in reports from Italy and the United Kingdom [3, 4], but similar to that reported in a recent study from the United States [9]. The potential contributions of patient characteristics, study methodologies, and viral variants to these discrepancies merit further study. Though the mechanisms underlying RNAemia’s contributions to multisystem pathology in both the acute and postacute phases, when persistent, remain to be elucidated, mounting evidence for its predictive value suggests that testing for SARS-CoV-2 RNAemia at presentation may help guide the triage, management, and prognosis of COVID-19.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Open Forum Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the additional author members of the Stanford COVID-19 Biobank Study Group, including Elizabeth J. Zudock, Marjan M. Hashemi, Kristel C. Tjandra, Jennifer A. Newberry, James V. Quinn, Ruth O’Hara, Euan Ashley, Rosen Mann, Anita Visweswaran, Thanmayi Ranganath, Jonasel Roque, Monali Manohar, Hena Naz Din, Komal Kumar, Kathryn Jee, Brigit Noon, Jill Anderson, Bethany Fay, Donald Schreiber, Nancy Zhao, Rosemary Vergara, Julia McKechnie, Aaron Wilk, Lauren de la Parte, Kathleen Whittle Dantzler, Maureen Ty, Nimish Kathale, Arjun Rustagi, Giovanny Martinez-Colon, Geoff Ivison, Ruoxi Pi, Maddie Lee, Rachel Brewer, Taylor Hollis, Andrea Baird, Michele Ugur, Drina Bogusch, Georgie Nahass, Kazim Haider, Kim Quyen Thi Tran, Laura Simpson, Michal Tal, Iris Chang, Evan Do, Andrea Fernandes, Allie Lee, Neera Ahuja, Theo Snow, and James Krempski. We would also like to thank Hien Nguyen, Lingxia Jiang, and Paul Hung from COMBiNATi, Inc., for all the material and technical support.

Financial support. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (Grants R01AI153133, R01AI137272, and 3U19AI057229 – 17W1 COVID SUPP #2) and a donation from Eva Grove.

Potential conflicts of interest. Yang is a Scientific Advisory Board member of COMBiNATi, Inc. All authors: no reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Ram-Mohan N, Kim D, Zudock EJ, et al. SARS-CoV-2 RNAemia predicts clinical deterioration and extrapulmonary complications from COVID-19. Clin Infect Dis 2021:ciab394. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fajnzylber J, Regan J, Coxen K, et al. . Massachusetts Consortium for Pathogen Readiness. SARS-CoV-2 viral load is associated with increased disease severity and mortality. Nat Commun 2020; 11:5493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Carfì A, Bernabei R, Landi F; Gemelli Against COVID-19 Post-Acute Care Study Group. Persistent symptoms in patients after acute COVID-19. JAMA 2020; 324:603–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Arnold DT, Hamilton FW, Milne A, et al. Patient outcomes after hospitalisation with COVID-19 and implications for follow-up: results from a prospective UK cohort. Thorax 2021; 76:399–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lund LC, Hallas J, Nielsen H, et al. Post-acute effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection in individuals not requiring hospital admission: a Danish population-based cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 2021; 21:1373–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hirschtick JL, Titus AR, Slocum E, et al. Population-based estimates of post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC) prevalence and characteristics. Clin Infect Dis 2021; 73:2055–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pretorius E, Vlok M, Venter C, et al. Persistent clotting protein pathology in long COVID/ post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC) is accompanied by increased levels of antiplasmin. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2021; 20:172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Patterson BK, Francisco EB, Yogendra R, et al. Persistence of SARS CoV-2 S1 protein in CD16+ monocytes in post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC) up to 15 months post-infection. Immunology. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chopra V, Flanders SA, O’Malley M, Malani AN, Prescott HC.. Sixty-day outcomes among patients hospitalized with COVID-19. Ann Intern Med 2021; 174:576–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.