Abstract

Genetic alterations in the rpoB gene were characterized in 50 rifampin-resistant (Rifr) clinical isolates of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex from Spain. A rapid PCR–enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) technique for the identification of rpoB mutations was evaluated with isolates of the M. tuberculosis complex and clinical specimens from tuberculosis patients that were positive for acid-fast bacilli (AFB). Sequence analysis demonstrated 11 different rpoB mutations among the Rifr isolates in the study. The most frequent mutations were those associated with codon 531 (24 of 50; 48%) and codon 526 (11 of 50; 22%). Although the PCR-ELISA does not permit characterization of the specific Rifr allele within each strain, 10 of the 11 Rifr genotypes were correctly identified by this method. We used the PCR-ELISA to predict the rifampin susceptibility of M. tuberculosis complex organisms from 30 AFB-positive sputum specimens. For 28 samples, of which 9 contained Rifr organisms and 19 contained susceptible strains, results were concordant with those based on culture-based drug susceptibility testing and sequencing. Results from the remaining two samples could not be interpreted because of low bacillary load (microscopy score of 1+ for 1 to 9 microorganisms/100 fields). Our results suggest that the PCR-ELISA is an easy technique to implement and could be used as a rapid procedure for detecting rifampin resistance to complement conventional culture-based methods.

Tuberculosis is a major health problem not only in developing countries but also in the developed world among high-risk groups, such as human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients, immigrants from countries in which tuberculosis is endemic, the homeless, and prison inmates (3, 20). The recent resurgence of tuberculosis in developed countries has been accompanied by an increase in the prevalence of drug-resistant disease. Resistance to rifampin is of particular importance since it is a marker for strains of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis that have been associated with outbreaks of disease in hospitals, prisons, and other institutions worldwide (2, 3, 5). The rate of rifampin resistance among strains of Mycobacterum tuberculosis isolated in Spain varies from 29% in patients who have previously received treatment (1) to 1.6% in those who have not received any prior antimycobacterial therapy (9).

Ninety-six percent of rifampin-resistant (Rifr) strains of M. tuberculosis possess genetic alterations within an 81-bp fragment of the rpoB gene that encodes the β subunit of DNA-dependent RNA polymerase (18, 26). Many different allelic variations have been detected within this region (11, 13, 18, 21), and specific rpoB genotypes are known to be associated with high-level rifampin resistance (15, 26). Molecular assays that have been used to screen the rpoB gene for rifampin resistance mutations include DNA sequencing (11), heteroduplex analysis (27), PCR single-stranded conformational polymorphism (21, 22), line probe assay (4, 6), mismatch analysis (14), and real-time PCR with fluorimetry (17, 24). Culture-based methods for detection of M. tuberculosis infection and susceptibility testing with antituberculosis drugs can take more than 1 month. A multicenter collaborative study showed that in specimens with positive smear results, the mean total time required for detection and antimicrobial susceptibility testing for M. tuberculosis was 18 days with the BACTEC method and 38.5 days using conventional culture methods (16). The application of genotypic methods for rapid testing of susceptibility to rifampin has important implications for efficient treatment and control of drug-resistant tuberculosis.

The objectives of this study were twofold: (i) to identify the rpoB mutations associated with rifampin resistance in a panel of M. tuberculosis complex strains isolated in Spain and (ii) to evaluate an assay system for the identification of rifampin resistance that is based on PCR amplification of the rpoB gene and the detection of mutations using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) capture probe method. Here we describe the use of this method to detect mutations in clinical isolates of the M. tuberculosis complex and directly in organisms within smear-positive clinical samples.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and clinical specimens.

Fifty clinical isolates of Rifr M. tuberculosis complex (49 M. tuberculosis isolates and 1 Mycobacterium bovis isolate) from 50 patients were included in the study. Eighteen samples were obtained from inmates confined to prisons in Madrid and were isolated between 1993 and 1999. The remaining 32 were obtained from the Mycobacterium Reference Laboratory, Majadahonda, Madrid, Spain, and were isolated from the population at large during 1997 to 1998 in different regions across the country. Six isolates of drug-susceptible M. tuberculosis representing five patients, one drug-susceptible M. tuberculosis reference strain (H37Rv ATCC 27294), and one Rifr M. tuberculosis reference strain (H37Rv ATCC 35838) were also included in the study. Fourteen isolates of nontuberculous mycobacteria that were recovered from respiratory specimens in our laboratory were also analyzed: Mycobacterium kansasii, Mycobacterium intracellulare, Mycobacterium fortuitum, Mycobacterium xenopi, Mycobacterium gordonae, Mycobacterium avium, Mycobacterium smegmatis, Mycobacterium chelonae, Mycobacterium szulgai, Mycobacteriums simiae, Mycobacterium peregrinum, Mycobacterium flavescens, Mycobacterium terrae, and Mycobacterium scrofulaceum. These strains were initially identified by biochemical means, and their identities were subsequently confirmed by PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of the hsp65 gene (23).

We also analyzed sputum specimens that were positive for acid-fast bacilli. To determine the limit of detection in smear-positive sputum specimens, M. tuberculosis culture-negative specimens from a single patient were pooled and aliquots were spiked with different numbers of M. tuberculosis bacilli (H37Rv ATCC 27294).

Processing of specimens.

All respiratory specimens were digested and decontaminated by the standard N-acetyl l-cysteine NaOH–Na citrate (NALC) method. Decontaminated specimens were used to prepare sputum smears, and the mycobacterial load was estimated by Ziehl-Neelsen staining according to conventional guidelines (scores, 1+ to 4+) (7). NALC pellets were inoculated onto pyruvate and nonpyruvate Löwenstein-Jensen slants (Hispanlab, Madrid, Spain) and incubated for up to 8 weeks at 37°C. Alternatively, they were inoculated into Mycobacteria Growth Indicator tubes (BACTEC MGIT960; Becton Dickinson, Sparks, Md.) and incubated for up to 6 weeks at the same temperature. All isolates were identified by standard biochemical tests and by probes for M. tuberculosis complex rRNA (Accuprobe; GenProbe, San Diego, Calif.). Susceptibility testing with isoniazid, rifampin, streptomycin, and ethambutol was performed using the BACTEC system (Becton Dickinson) and/or the proportion method with Löwenstein-Jensen medium as carried out by the Mycobacterium Reference Laboratory.

Extraction of DNA from cultures and clinical samples.

All procedures to extract DNA were performed in a biological safety cabinet. DNA from cultures was prepared by chloroform-isoamyl alcohol extraction as previously described (12), following a preliminary step to inactivate the sample by heating at 95°C for 10 min. Alternatively, a rapid-extraction method was used in which a bacterial colony was suspended in 200 μl of Tris-EDTA buffer, heated at 95°C for 10 min, and sonicated in an ultrasonic water bath for 10 min at room temperature. Cellular debris was then removed by centrifugation, and 10 μl of the supernatant was used in the PCR.

For DNA extraction from sputum specimens, 0.5 ml of decontaminated specimen was transferred to a sterile screw-cap microcentrifuge tube and inactivated by heating at 80°C for 20 min. Samples were then centrifuged, and the pellet was washed with sterile distilled water. After recentrifugation the pellet was resuspended in 100 μl of lysis buffer containing proteinase K (0.25 mg/ml) and incubated at 56°C for 1 h followed by at 95°C for 10 min. Samples were then centrifuged, and 10 μl of supernatant was used for PCR amplification.

In order to check for possible contamination, a negative control consisting of all the reagents except target DNA was run in parallel with the samples in every set of amplification reactions.

PCR amplification.

The oligonucleotides used for PCR amplification have been reported previously by Ohno et al. (15): forward primer, RP4T (5′-GAGGCGATCACACCGCAGACGT-3′), and reverse primer, RP8T (5′-GATGTTGGGCCCCTCAGGGGTT-3′). This pair of primers amplifies a 255-bp fragment of the rpoB gene that includes the region in which the mutations conferring rifampin resistance have been described. In our experiments, the reverse primer was labeled with digoxigenin at the 5′ end to facilitate detection of the PCR product. PCR amplification was carried out in a 100-μl final volume containing 0.25 μM RP4T and 0.25 μM digoxigenin-labeled RP8T (ISOGEN); 1× Taq DNA polymerase buffer; 1.5 mM MgCl2; 250 μM concentrations each of dATP, dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP; 2.5 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Promega); and 10 μl of sample. Amplification was initiated by denaturing the sample for 10 min at 94°C, followed by 40 cycles of 1 min at 94°C, 1 min at 65°C, and 1 min at 72°C. Finally, samples were held at 72°C for 10 min to ensure complete extension of all PCR products.

Probe selection and capture probe hybridization.

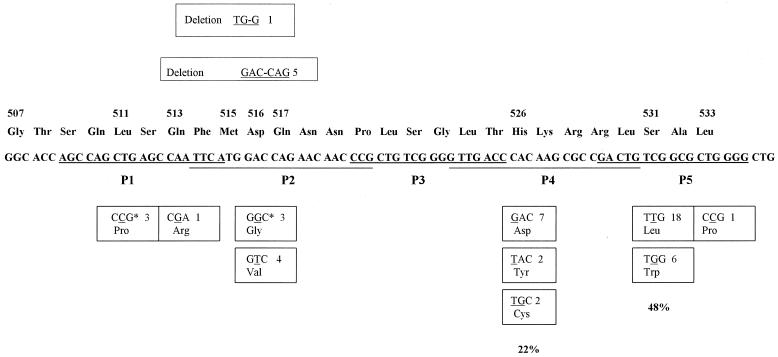

Five overlapping 5′-biotinylated oligonucleotides were designed as capture probes for the detection of the rpoB PCR products (Fig. 1). The five probes are specific for the wild-type M. tuberculosis rpoB gene and span the region in which mutations conferring rifampin resistance have been described (13).

FIG. 1.

Frequency of mutations in the rpoB gene in 50 clinical isolates of rifampin-resistant M. tuberculosis complex from Spain. The positions of deletions are illustrated above the wild-type sequence, and missense mutations are recorded below. The frequency with which each mutation was encountered in this study is indicated. Nucleotide sequences of the five probes used for hybridization are underlined (P1 to P5). ∗, the three isolates showed a double mutation in codons 511 and 516.

The detection of the digoxigenin-labeled amplified DNA was carried out using the VISU-GEN system (Pharma Gen). Briefly, each capture probe was first immobilized to a streptavidin-coated microtiter plate well (Labsystems) by incubation for 15 min at room temperature in binding solution. Five wells were used for each PCR-amplified sample, one well for each capture probe. After three washes with phosphate-buffered saline containing Tween 20 (PBS-T), 100 μl of high-stringency hybridization buffer and 10 μl of heat-denatured PCR product were added to each well. Hybridization between the amplified DNA and the capture probe was carried out at 55°C for 1 h. After three washes with PBS-T, hybridized PCR products that remained bound to the well were detected by incubation for 1 h at room temperature with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antidigoxigenin antibody (Roche Diagnostics). Wells were then washed and 100 μl of the color-developing peroxidase substrate (Roche Diagnostics) was added. After incubation for 1 h at room temperature, optical density (OD) at 405 nm was measured using a Multiskan RC microtiter plate reader (Labsystems).

DNA sequencing.

Primers RP4T and RP8T were used to amplify a 255-bp fragment of rpoB gene that includes the 81-bp core region. Automated DNA sequencing analysis of both strands of the PCR products was performed using an ABI Prism Model 310 DNA sequencer.

RESULTS

rpoB mutations.

DNA sequencing identified mutations in the 81-bp core region of the rpoB gene in all Rifr clinical isolates of M. tuberculosis complex included in the study, while no such mutations were observed in the six rifampin-susceptible (Rifs) strains. The Rifr reference strain (H37Rv ATCC 35838) had a mutation in codon 531 (C→T). Eleven distinct genetic alterations were present among the 50 clinical isolates (Fig. 1), with replacement of TCG by TTG in codon 531 the most common, occurring in 18 Rifr isolates (36%), including the clinical isolate of M. bovis. Overall, mutations in codons 531 and 526 accounted for rifampin resistance in 48 and 22% of clinical strains, respectively.

Sensitivity and specificity of the PCR-ELISA.

A search of the GenBank database with the BLAST program was performed to confirm the specificity of the PCR primers and ELISA probes for the M. tuberculosis complex. The specificity of the assay was demonstrated experimentally by analysis of cell lysates from 14 different species of nontuberculous mycobacteria. No PCR products from these specimens were visible on agarose gel electrophoresis and, in all cases, hybridization in the PCR-ELISA gave ODs of <0.35 for all five rpoB probes.

The five probes used in the PCR-ELISA are specific for the wild-type M. tuberculosis rpoB gene sequence. A positive result with any particular probe therefore indicated the absence of any mutations in that region, while a negative result indicated a lack of hybridization and the presence of a mutation in the rpoB sequence corresponding to the probe. Because not all probes were found to work with equal efficiency, several different probes were designed and tested in order to identify those that gave the best discrimination between the various wild-type and mutant rpoB alleles. Additional experiments were then performed using purified M. tuberculosis DNA and spiked sputum specimens to define an objective algorithm by which to interpret the results.

The sensitivity of the PCR-ELISA was determined by assaying PCR products generated from 10-fold serial dilutions of DNA isolated from a Rifs strain of M. tuberculosis (H37Rv ATCC 27294). An M. tuberculosis DNA concentration of 0.1 pg/reaction was required in order to produce an OD of >1.0 with at least one of the probes and of >0.35 with all five. Amplification of 10 fg of M. tuberculosis DNA gave ODs which varied between 0.1 and 0.8, depending on the probe. Clinical sensitivity was estimated using dilutions of bacteria (H37Rv ATCC 27294) in PBS-T that were seeded into pooled culture-negative sputum samples. Samples containing ≥103 CFU/ml gave ODs of >0.35 for all five probes, with at least one having an OD of >1.0. Samples containing 102 CFU/ml gave ODs which varied between 0.2 and 0.7. Negative PCR samples containing distilled water in place of target DNA consistently yielded ODs of <0.1 for all probes, and M. tuberculosis culture-negative sputum samples reproducibly gave ODs of <0.15.

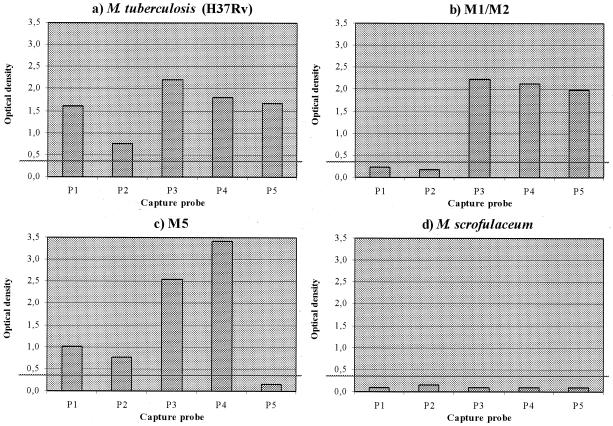

Based on the above data, we applied the following criteria for the interpretation of PCR-ELISA results from clinical specimens. Results for a given sample were only considered valid if at least one of the probes yielded an OD of ≥1.0 and if none gave an OD between 0.25 and 0.35. Results that failed to meet these criteria were considered indeterminate. For samples that satisfied the above criteria, individual probes that gave OD values of >0.35 were considered positive, while those with values of <0.25 were considered negative. The requirement that at least one probe should yield an OD that was ≥1.0 was introduced to distinguish instances in which the lack of signal was due to failure of the PCR (i.e., the sample was negative for M. tuberculosis or inhibitory or contained a target level below the detection limit of the assay) rather than due to a mutation in the rpoB gene sequence (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Representative data from four cell lysates. Graphs show the OD405 for each capture probe (P1 to P5). The cutoff for a positive result is represented by a horizontal line (OD > 0.35). The samples plotted are the following: drug-susceptible M. tuberculosis reference strain H37Rv (a); clinical isolate of Rifr M. tuberculosis, mutant for regions 1 and 2 (mutant 511 [T→C] and 516 [A→G] as determined by DNA sequencing) (b); clinical isolate of Rifr M. tuberculosis, mutant for region 5 (mutant 531 [C→T]) as determined by DNA sequencing) (c); and clinical isolate of M. scrofulaceum (identified by PCR amplification of the hsp65 gene) (d).

PCR-ELISA to detect rpoB mutations in M. tuberculosis cultures.

The ability of the PCR-ELISA to identify mutations in the core region of the rpoB gene was assessed using cell lysates from 11 Rifr and 6 Rifs M. tuberculosis complex strains. The 11 Rifr organisms represented the 11 different rpoB mutations identified by sequence analysis during the present study. Ten of these mutants were correctly identified by the PCR-ELISA. One strain with a mutation in codon 533 gave an OD of 0.5 with probe P5 and ODs of >1.25 with the other four probes. Thus, this mutation is not detected by the PCR-ELISA.

Because none of the samples of this study were found to have a mutation in the region of the rpoB gene covered by the P3 probe, we decided to validate this probe in an indirect manner. An 18-bp oligonucleotide probe (P3-M) with the same sequence as P3 except for a single base corresponding to the most frequent mutation reported for that region (T instead of C in codon 522) was tested in the PCR-ELISA. As expected, all samples gave ODs of <0.25 using this probe.

PCR-ELISA to detect rpoB mutations in smear-positive clinical specimens.

We evaluated the usefulness of the rpoB PCR-ELISA in predicting rifampin susceptibility in a panel of 30 smear-positive sputum samples. Nine specimens were obtained from seven patients with confirmed Rifr tuberculosis, while the remaining 21 specimens were from 21 patients with drug-susceptible disease. Five smear- and culture-negative samples from five patients who did not have tuberculosis were used as negative controls. The investigator who performed the PCR-ELISA was blinded to the panel of specimens.

The results of this study are summarized in Table 1. All samples from patients who did not have tuberculosis were negative by the assay. Nineteen of 21 (90%) smear-positive samples containing Rifs organisms were correctly identified by the PCR-ELISA. The remaining two smear-positive samples from patients with Rifs disease had a microscopy score of 1+ and failed to yield an OD of >1.0 for any of the five probes. The results from these samples were therefore considered indeterminate. All nine (100%) of the smear-positive samples containing Rifr M. tuberculosis were correctly identified by the PCR-ELISA. Sequence analysis demonstrated that the probes which yielded negative results in the PCR-ELISA (OD < 0.25) corresponded with the locations of the mutations in the rpoB sequences of these strains (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Direct detection of M. tuberculosis rpoB mutations in 30 sputum specimens by PCR-ELISA

| Microscopy scorea (no. of samples) | PCR-ELISA resultb | rpoB mutation | Predicted rifampin phenotypec | Rifampin susceptibility resultc |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4+ (1) | P5 | 531 (C→T) | R | R |

| 4+ (1) | P2 | 516 (A→T) | R | R |

| 4+ (1) | P4 | 526 (C→G) | R | R |

| 4+ (1) | P1–P2 | 511 (T→C); 516 (A→G) | R | R |

| 4+ (1) | P5 | 531 (C→G) | R | R |

| 3+ (2) | P2 | Deletion of 515–516 (TG–G) | R | R |

| 1+ (1) | P2 | Deletion of 515–516 (TG–G) | R | R |

| 1+ (1) | P5 | 531 (C→T) | R | R |

| 4+ (3) | Wild type | S | S | |

| 3+ (11) | Wild type | S | S | |

| 2+ (3) | Wild type | S | S | |

| 1+ (2) | Wild type | S | S | |

| 1+ (2) | NI | S |

Clinical specimens were examined by microscopy after Ziehl-Neelsen staining. The bacillary load was scored according to the scale of the American Society for Microbiology (1+, 1 to 9 organisms/100 fields; 2+, 1 to 9 organisms/10 fields; 3+, 1 to 9 organisms/field; 4+, >9 organisms/field).

Probes that were negative for hybridization with the PCR-amplified product are shown. NI, noninterpretable.

R, resistant; S, susceptible.

DISCUSSION

In this study, 50 clinical isolates of Rifr M. tuberculosis complex organisms from Spain were characterized by sequencing of the 81-bp core region of the rpoB gene. We also evaluated the application of a PCR-ELISA for fast and accurate detection of mutations in the rpoB gene and the prediction of rifampin susceptibility of M. tuberculosis in clinical samples.

rpoB mutations were identified in all clinical isolates of Rifr M. tuberculosis. A total of 11 different genetic alterations were found with mutations in codons 531 and 526 occurring in 70% of Rifr isolates. These results agree with previous reports from other countries that >96% of Rifr M. tuberculosis strains contain mutations within the 81-bp hypervariable region of the rpoB gene (13) and that ≥70% of these mutations occur in codons 531 and 526 (4, 10, 19, 21, 26). Earlier reports also suggest that there is no significant difference in the distribution of mutations among the Rifr M. tuberculosis isolates from different countries.

The ability to determine susceptibility to rifampin in a few hours has important implications for clinical management of individual patients and for tuberculosis control programs as a whole. For this reason, we evaluated a PCR-ELISA method for detecting mutations in the rpoB gene of M. tuberculosis and the usefulness of this system for determining rifampin susceptibility directly from clinical samples. The PCR-ELISA was able to detect as little as 0.1 pg of purified M. tuberculosis DNA per amplification reaction and the equivalent of 103 CFU/ml in spiked, culture-negative sputum. The PCR-ELISA is therefore sufficiently sensitive not only for detection of rifampin resistance in cultured organisms but also for direct detection in clinical specimens. We also confirmed that the PCR-ELISA system is specific for the M. tuberculosis complex, thereby avoiding misinterpretation of results due to amplification of nontuberculous mycobacteria present in the sample. The specificity of the assay might provide for simultaneous susceptibility testing and identification of M. tuberculosis complex organisms.

Overall, the results of the PCR-ELISA agreed with those obtained by DNA sequencing. The assay was able to detect 10 out of 11 different rpoB mutations observed in this study, including those in codons 531 and 526, which are the most frequent genetic alterations found in Spain and other countries (4, 8, 10, 19, 21, 26). Only one Rifr strain with a mutation in codon 533 was not detected by the PCR-ELISA. This mutation is reported to occur very infrequently, comprising just 1.9% of all mutations described in the rpoB core region (13). Further studies are necessary to determine whether additional mutations exist which cannot be detected by the PCR-ELISA.

A practical application for this assay would be in the rapid prediction of susceptibility to rifampin in smear-positive clinical samples obtained from patients suspected of harboring drug-resistant M. tuberculosis. These include patients with a history of previous tuberculosis, recent immigrants or those who have traveled to an area with a high prevalence of drug-resistant disease, patients who fail to respond to therapy, or contacts of individuals with known multidrug-resistant infections.

We successfully applied the PCR-ELISA to 28 out of 30 (93%) smear-positive sputum samples from tuberculosis patients. The two specimens that yielded indeterminate results contained levels of bacteria that are very close to the detection limit of the assay (microscopy score, 1+). Unequal distribution of organisms throughout the specimens may also have contributed to these results. In all cases in which a valid PCR-ELISA result was obtained, susceptibility to rifampin as determined by this method correlated with that obtained by conventional culture-based techniques. Furthermore, among Rifr strains, the probe that failed to hybridize to the PCR product corresponded with the position of the mutation in the rpoB gene as identified by sequence analysis. The PCR-ELISA cannot identify the specific mutation causing rifampin resistance but does indicate the region in which the mutation is located. Knowledge of the specific mutation conferring resistance is, however, not necessary for efficient patient management. The benefits of the PCR-ELISA system lie in its speed and accuracy in identifying Rifr strains. Larger studies will be needed to evaluate the sensitivity of the assay and determine the positive and negative predictive values of results obtained with clinical samples.

The PCR-ELISA system that we describe here utilizes commonly available reagents and equipment and is simple to perform, requiring only a basic understanding of molecular techniques. The entire procedure, including DNA extraction, PCR amplification, and ELISA detection, can be performed in a single working day. Importantly, results can be analyzed objectively, thereby eliminating the possibility of misinterpretation by different investigators. We have demonstrated the ability of the system to detect rifampin resistance directly in smear-positive sputum samples as well as in cultured organisms. Furthermore, in combination with culture in liquid medium, the PCR-ELISA could reduce the time required to detect rifampin resistance in smear-negative sputum samples and culture-positive specimens. Given the correlation that has been observed between rifampin resistance in M. tuberculosis and resistance to other antimycobacterial drugs (21, 25), the PCR-ELISA system provides a rapid means of screening for potentially multidrug-resistant strains. The application of such rapid molecular methods to the detection of rifampin resistance will therefore have an important impact in the future control of drug-resistant tuberculosis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Tobin Hellyer for his suggestions and comments and M. S. Jimenez (Mycobacterium Reference Laboratory, Madrid, Spain) for providing some mycobacterial strains.

This study was supported by the Comision Interministerial de Ciencia y Tecnología (95-0180-OP) of Spain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ausina V, Riutort N, Viñado B, Manterola J M, Ruiz-Manzano J, Rodrigo C, Matas L, Gimenez M, Tor J, Roca J. Prospective study of drug-resistant tuberculosis in a Spanish urban population including patients at risk for HIV infection. Eur J Clin Microbiol Dis. 1995;14:105–110. doi: 10.1007/BF02111867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bifani P J, Plikaytis B B, Kapur V, Stockbauer K, Pan X, Lutfey M L, Moghazeh S L, Esisner W, Daniel T M, Kaplan M H, Crawford J T, Musser J M, Kreiswirth B N. Origin and interstate spread of a New York city multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis clone family. JAMA. 1996;275:452–457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chaves F, Dronda F, Cave M D, Alonso-Sanz M, Gonzalez-Lopez A, Eisenach K D, Ortega A, Lopez-Cubero L, Fernandez-Martin I, Catalan S, Bates J H. A longitudinal study of transmission of tuberculosis in a large prison population. Am J Res Crit Care Med. 1997;155:719–725. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.2.9032218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cooksey R C, Morlock G P, Glickman S, Crawford J T. Evaluation of a line probe assay kit for characterization of rpoB mutations in rifampin-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from New York City. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1281–1283. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.5.1281-1283.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coronado V G, Beck-Sague C M, Hutton M D, Davis B J, Nicholas P, Villareal C, Woodley C L, Kilburn J O, Crawford J T, Frieden T R, Sinkowitz R L, Jarvis W R. Transmission of multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis among persons with human immunodeficiency virus infection in an urban hospital: epidemiologic and restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis. J Infect Dis. 1993;168:1052–1055. doi: 10.1093/infdis/168.4.1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Beenhouwer H, Lhiang Z, Jannes G, Mijs W, Machtelinckx L, Rossau R, Traore H, Portaels F. Rapid detection of rifampicin resistance in sputum and biopsy specimens from tuberculosis patients by PCR and line probe assay. Tuber Lung Dis. 1995;76:425–430. doi: 10.1016/0962-8479(95)90009-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ebersole L L. Acid-fast stain procedures, section 3.5.1. In: Isenberg H D, editor. Clinical microbiology procedures handbook. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gonzalez N, Torres M J, Aznar J, Palomares J C. Molecular analysis of rifampin resistance of Mycobacterium tuberculosis clinical isolates in Seville, Spain. Tuber Lung Dis. 1999;79:187–190. doi: 10.1054/tuld.1998.0195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grupo de Estudio de tuberculosis resistente en Madrid. Estudio transversal multihospitalario de tuberculosis y resistencias en Madrid (octubre 1993–abril 1994) Med Clin (Barcelona) 1996;106:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirano H, Abe C, Takahashi M. Mutations in the rpoB gene of rifampin-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains isolated mostly in Asian countries and their rapid detection by line probe assay. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:2663–2666. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.8.2663-2666.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kapur V, Li L-L, Iordanescu S, Hamrick M R, Wanger A, Kresiswirth B N, Musser J M. Characterization by automated DNA sequencing of mutations in the gene (rpoB) encoding the RNA polymerase β subunit in rifampin-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains from New York City and Texas. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1095–1098. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.4.1095-1098.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murray M G, Thompson W F. Rapid isolation of high molecular weight plant DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1980;8:4321–4325. doi: 10.1093/nar/8.19.4321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Musser J M. Antimicrobial agent resistance in mycobacteria: molecular genetic insights. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1995;8:496–514. doi: 10.1128/cmr.8.4.496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nash K A, Gaytan A, Inderlied C B. Detection of rifampin resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis by means of a rapid, simple, and specific RNA/RNA mismatch. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:533–536. doi: 10.1086/517283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ohno H, Koga H, Kuroita T, Tomono K, Ogawa K, Yanagihara K, Yamamoto Y, Myamoto J, Tashiro T, Kohno S. Rapid prediction of rifampin susceptibility of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;155:2057–2063. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.6.9196115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pfaller M A. Application of new technology to the detection, identification, and antimicrobial susceptibility testing of mycobacteria. Am J Clin Pathol. 1994;101:329–337. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/101.3.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Piatek A S, Tyagi S, Pol A C, Telenti A, Miller L P, Kramer F R, Alland D. Molecular beacon sequence analysis for detecting drug resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat Biotechnol. 1998;16:359–363. doi: 10.1038/nbt0498-359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ramaswamy S, Musser J M. Molecular genetic basis of antimicrobial agent resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: 1998 update. Tuber Lung Dis. 1998;79:3–29. doi: 10.1054/tuld.1998.0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scarpellini P, Braglia S, Carrera P, Cedri M, Cichero P, Colombo A, Crucianelli R, Gori A, Ferrari M, Lazzarin A. Detection of rifampin resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis by double gradient-denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:2550–2554. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.10.2550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sepkowitz K A, Raffalli J, Riley L, Kiehn T E, Armstrong D. Tuberculosis in the AIDS era. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1995;8:180–199. doi: 10.1128/cmr.8.2.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Telenti A, Imboden P, Marchesi F, Lowrie D, Cole S, Colston M J, Matter L, Schopfer K, Bodmer T. Detection of rifampin-resistance mutations in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Lancet. 1993;341:647–650. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)90417-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Telenti A, Imboden P, Marchesi F, Schmidheini T, Bodmer T. Direct, automated detection of rifampin-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis by polymerase chain reaction and single-strand conformation polymorphism analysis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:2054–2058. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.10.2054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Telenti A, Marches F, Bald M, Badly F, Bottger E, Bodmer T. Rapid identification of mycobacteria to the species level by polymerase chain reaction and restriction enzyme analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:175–178. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.2.175-178.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Torres M J, Criado A, Palomares J C, Aznar J. Use of real-time PCR and fluorimetry for rapid detection of rifampin and isoniazid resistance-associated mutations in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:3194–3199. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.9.3194-3199.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Watterson S A, Wilson S M, Yates M D, Drobbiewski F A. Comparison of three molecular assays for rapid detection of rifampin resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:1969–1973. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.7.1969-1973.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Williams D L, Spring L, Collins L, Miller L P, Heifets L B, Gangadharam P R J, Gillis T P. Contribution of rpoB mutations to development of rifamycin cross-resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:1853–1857. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.7.1853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Williams D L, Spring L, Salfinger M, Gillis T P, Persing D H. Evaluation of polymerase chain reaction-based universal heteroduplex generator assay for direct detection of rifampin susceptibility of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from sputum specimens. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:446–450. doi: 10.1086/516313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]