Abstract

Background:

It has been postulated that inadequate clearance of the amyloid β protein (Aβ) plays an important role in the accumulation of Aβ in sporadic late onset Alzheimer’s disease (AD). While the blood brain barrier (BBB) has taken the center stage in processes involving Aβ clearance, little information is available about the role of the lymphatic system. We previously reported that Aβ is cleared through the lymphatic system. We now re-assessed lymphatic Aβ clearance by treating a mouse model of AD amyloidosis with melatonin, an Aβ aggregation inhibitor and immuno-regulatory neurohormone.

Objective:

To confirm and expand our initial finding that Aβ is cleared through the lymphatic system. Lymphatic clearance of metabolic and cellular “waste” products from the brain into the peripheral lymphatic system has been known for a long time. However, except for our prior report, there is no additional experimental data published about Aβ being cleared into peripheral lymph nodes.

Methods:

For these experiments, we used a transgenic mouse model (Tg2576) that over-expresses a mutant form of the Aβ precursor protein (APP) in the brain. We examined levels of Aβ in plasma and in lymph nodes of transgenic mice as surrogate markers of vascular and lymphatic clearance, respectively. Aβ levels were also measured in the brain and in multiple tissues.

Results:

Clearance of Aβ peptides through the lymphatic system was confirmed in this study. Treatment with melatonin led to the following changes: 1-A statistically significant increase in soluble monomeric Aβ40 and an increasing trend in monomeric Aβ42 in cervical and axillary lymph nodes of treated mice. 2-Statistically significant decreases in oligomeric Aβ40 and a decreasing trend in Aβ42 in the brain.

Conclusion:

The data expands on our prior report that the lymphatic system participates in Aβ clearance from the brain. We propose that abnormalities in Aβ clearance through the lymphatic system may contribute to the development of cerebral amyloidosis. Melatonin and related indole molecules (i.e., indole-3-propionic acid) are known to inhibit Aβ aggregation although they do not reverse aggregated Aβ or amyloid fibrils. Therefore, these substances should be further explored in prevention trials for delaying the onset of cognitive impairment in high risk populations.

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is characterized by brain deposits of mostly 40 to 42 amino acid peptides, the amyloid β protein (Aβ), in senile plaques and intracranial blood vessels (1). Aβ exhibits a strong tendency to aggregate into neurotoxic oligomeric forms (2). The “amyloid hypothesis” of AD proposes that elevated levels of Aβ oligomers trigger a downstream cascade of oxidative (3-6) and pro-inflammatory (7) events which may contribute to the widespread death of neurons and dementia (8).

Although genetic forms of AD are associated with increased production of the longer Aβ42 species that tends to aggregate more rapidly, extensive studies have not detected such increases in typical late onset AD (LOAD), where the cause of Aβ accumulation remains unknown. Inadequate clearance of Aβ has been proposed to play a significant role in Aβ accumulation in LOAD (9); however, attention has almost exclusively been focused on the blood brain barrier (BBB) as the principal pathway for Aβ clearance with the lymphatic system remaining largely overlooked. Although the parenchyma of the brain does not contain lymphatic channels, numerous investigations in rodents, primates and humans have revealed multiple systems that operate simultaneously to clear cellular waste products from the brain into the peripheral lymphatic system (for review see (10, 11).

Recently, we have published data connecting brain Aβ accumulation with the peripheral lymphatic system in a mouse model of amyloidosis (12). Here, we evaluated the role of the lymphatic system in the removal of Aβ from brain tissue after treating AD transgenic mice with melatonin, an Aβ aggregation inhibitor and neuroprotective molecule (13-20). Melatonin has been originally proposed to play a potential role in AD (13, 14). In addition, melatonin has several immune-regulatory properties which could potentially contribute to the phenomenon reported in this paper (21, 22). For these experiments, we used a transgenic mouse model (Tg2576) that over-expresses a mutant form of the Aβ precursor protein (AβPP) in the brain (23). Tg2576 mice accumulate Aβ in the brain and develop cognitive abnormalities (23). By using melatonin, we attempted to increase the brain ratio of monomeric to oligomeric Aβ in Tg2576, facilitating Aβ clearance from the brain through the lymphatic system.

Materials and Methods

AD transgenic mice

We used the transgenic mice Tg2576 that over-express the 695-amino-acid isoform of human AβPP containing a Lys670→ Asn and a Met 671→ Leu mutation found in a Swedish family with early onset AD (23). The animals were genotyped twice, at birth and after sacrifice, using a standard PCR protocol. Mice were terminated and tissues were collected at 4 months plus one week of age and 15.5 months of age. Mice were housed up to 4 to a cage in air-conditioned rooms at 22 °C with alternating twelve hours of light and darkness and fed ad libitum with AIN76A (Bethlehem, PA, USA). The Institutional Animal Review Board approved the use of mice for this study which complied with the National Institutes of Health guide for the care and use of laboratory animals.

Aβ measurement in tissue from mice

We examined Aβ levels in plasma and in lymph nodes of Tg2576 mice as surrogate markers of vascular and lymphatic clearance, respectively. Aβ levels were also measured in multiple tissues as indicated below. Upon sacrifice, cerebral frontal cortex and cervical and axillary lymph nodes (as well as several organs) were dissected and homogenized for ELISA quantification as described (9, 12). These lymph nodes sites are known to “connect” with the brain in an immunological sense (12). Due to their extremely small size, which required a tedious dissection using a neurosurgical microscope, the cervical and axillary lymph nodes in individual animals were combined to provide adequate tissue quantity for the measurements. Soluble Aβ40 was quantified in homogenates from fractions extracted with Tris-saline (TS) buffer (150mg/ml). As characterized previously (24-26), we used the 100,000 x g supernatants with the BNT77-BA27 in ELISA to mainly quantify monomeric Aβ x-40 (Wako, Osaka, Japan) or the BNT77-BC05 in ELISA to mainly quantify monomeric Aβ x-42 (Wako, Osaka, Japan). The obtained values were normalized to the wet tissue weight. Quantification of oligomeric Aβ was performed as described (27). Briefly, microplates (Maxisorp White Microplate, Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) were pre-coated with monoclonal 2C3 for antigen capture (27, 28), and sequentially incubated for 24 h at 4°C with 100 μl of the different samples followed by 24-hour incubation at 4°C with horseradish-peroxidase-conjugated BA27 Fab’ fragment (anti- 1-40, Wako, Osaka, Japan) or horseradish-peroxidase-conjugated BC05 Fab’ fragment (anti-Aβ 35-43, Wako, Osaka, Japan). The conjugate was detected by chemiluminescence using the SuperSignal ELISA Pico substrate (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA) on a Veritas Microplate Luminometer (Promega, Madison, WI).

Melatonin treatment of mice.

Melatonin treatment, 2 mg/ml in drinking water, started at 4 months of age, and continued until euthanasia after 1 week or at 15.5 months of age. Ultrapure pharmaceutical grade melatonin (Helsinn Pharmaceuticals, Biasca, Switzerland) was dissolved in hydroxymethylcyclodextrin at a concentration of 50 mg/ml and subsequently diluted in the drinking water to a final concentration of 2 mg/ml. An equal amount of vehicle without melatonin was added to the drinking water of untreated mice. Treated and untreated animals consumed similar quantities of fluid (an average of 3 ml/day) as estimated by periodic body weights and water measurements. The treatment was initiated at 4 months of age and independent groups of treated and control cohorts were sacrificed at 4 months (baseline measurements after a 1-week treatment) and at 15.5 months (15 months and 2 weeks treatment).

Statistical analysis

Where applicable, the data were analyzed by comparing the groups by the F test (when the variances were different in the groups being compared; i.e., at 15.5 months) or by a two-tailed t test (when the variances were not different; i.e., at 4 months), with the statistical software using GraphPad Prism for Windows, (GraphPad Software, San Diego, California). Sample size (n) for each treatment is noted in the figures by ticks. Typically, we lose about 40-50% of these transgenic animals in an aging study. Some of the treated groups for the 15.5 months had a larger “n” than untreated groups because melatonin treatment eliminated early deaths, reducing attrition dramatically to non-transgenic levels.

Results

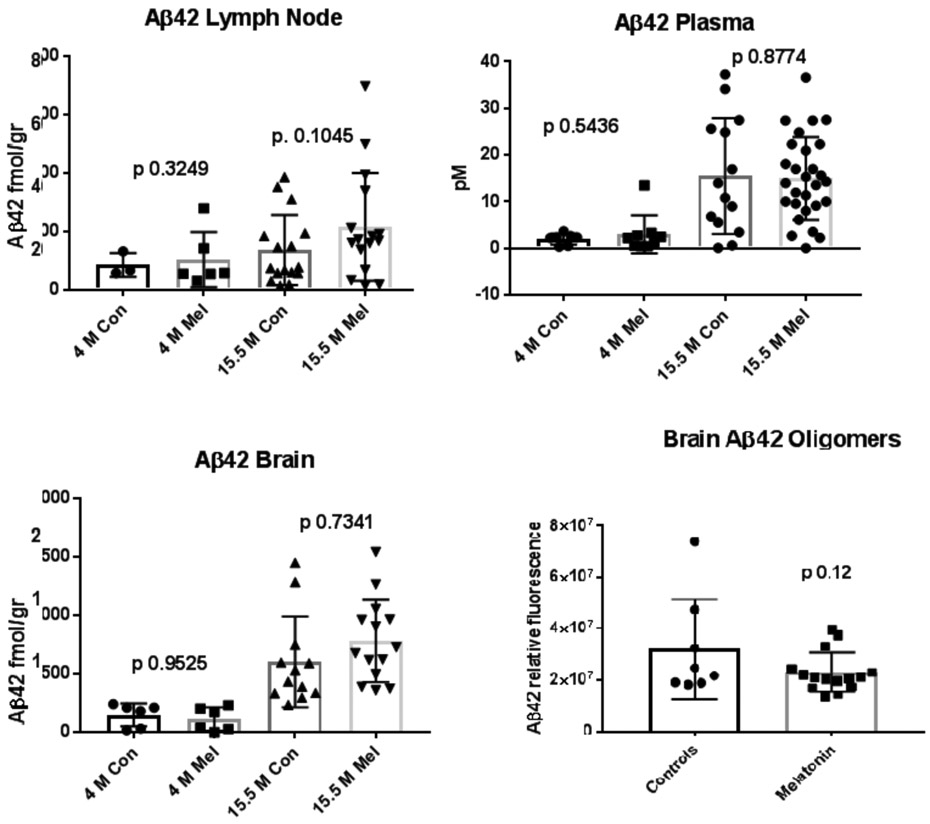

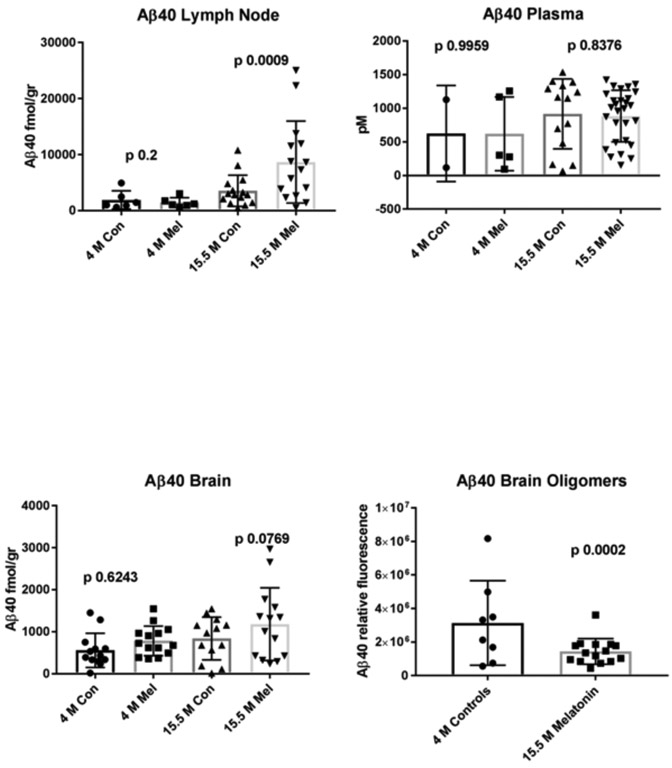

As predicted by its anti-aggregation properties, melatonin treatment yielded an increase in soluble monomeric Aβ40 in brain (strong trend; p 0.07) and lymph nodes (significant: p 0.017) at 15.5 months, compared to untreated (control) mice. This increase was not observed for Aβ42 in the brain, although we observed a moderate trend in the same direction in lymph nodes (p 0.1) (figure 2). Aβ was undetectable in control splenic lymphatic tissue and either undetectable or at very low levels in several other control tissues from the same mice such as the heart, liver, kidney, lung and intestine, strongly suggesting that the Aβ peptides found in the lymph nodes are derived from the brain (not shown). Remarkably, treated animals at 15.5 months also showed a significant decrease in oligomeric Aβ40 and a decreasing trend in Aβ42 in the brain when compared to untreated mice of the same age (Figures 1 and 2). In contrast, plasma Aβ levels at 15.5 months remained unchanged by treatment suggesting that clearance through the lymphatic system may be more effective than through the BBB at the ages studied in this model.

FIGURE 2.

Saline soluble monomeric Aβ42 in control and melatonin treated mice. Brain and lymph node homogenates in saline along with plasma (B) from Tg2576 mice were evaluated by a sensitive and specific ELISA assay as shown for figure 1. The n values for control (Con) and melatonin (Mel)-treated samples from 4 and 15.5 month-old animals are listed in order for lymph node (n=3, 6, 16, 16); plasma (n=3, 5, 14, 28) and brain (n=3, 2, 13, 14). Aβ40 oligomers measurements in brain at 15.5 age months are also shown in controls and after treatment with melatonin (n= 8; 15). As shown in figure 1, Aβ42 oligomers measurements in brain are shown at 15.5 age months in controls and after treatment with melatonin (n=8; 15). Con = Control mice. Mel = Melatonin treated mice. As mentioned for figure 1, acceptable and consistent Aβ42 oligomer standards are not available to establish curves; thus, we have compared the relative luminescence values detected in brain extracts from control and melatonin-treated mice. As with Aβ40, oligomeric Aβ42 was not detectable in plasma or in lymph nodes.

Figure 1.

Saline soluble monomeric Aβ40 in control and melatonin treated mice. Brain and lymph node homogenates in saline along with plasma (B) from Tg2576 mice were evaluated by a sensitive and specific ELISA assay for Aβ40. The n values for control (Con) and melatonin (Mel)-treated samples from 4 and 15.5 month-old animals are listed in order for lymph node (n=6, 6, 15, 15); plasma (n=2, 5, 14, 28) and brain (n=12, 14, 13, 14); Aβ40 oligomers measurements in brain at 15.5 age months are also shown in controls and after treatment with melatonin (n= 8, 16). Con = Control mice. Mel = Melatonin treated mice. Since acceptable and consistent Aβ oligomer standards are not available to establish curves, we have compared the relative luminescence values detected in brain extracts from control and melatonin-treated mice. Oligomeric Aβ40 was not detectable in plasma or in lymph nodes (not shown). Some of the untreated control groups have lesser numbers of animals than the treated groups, mostly reflecting premature deaths (known attrition rate in AD transgenics) and to a lesser degree, to inadvertent tissue/sample loss. Melatonin dramatically increased survival in the treated groups to levels comparable to non-transgenic mice (not shown).

Discussion

Previously, we presented evidence of Aβ clearance through the peripheral lymphatic system in a mouse model of amyloidosis (12). Here, the data further confirms and advances our knowledge regarding this pathway for Aβ clearance. Although the brain parenchyma lacks lymphatic vessels, several mechanisms involving the lymphatic system have been proposed to participate in the clearance of cellular debris and metabolic waste from the mammalian central nervous system (10, 11). These include pathways along cranial nerves, spinal nerves, the cribriform plate, meningeal lymphatic channels and paravascular pathways including the glymphatic system (10, 11). In addition to the pathways of clearance mentioned here, it is likely that active cellular transport mechanisms are in play. For example, the murine PirB (paired immunoglobulin-like receptor B) and its human ortholog LilrB2 (leukocyte immunoglobulin-like receptor B2), present in human brain, are receptors for Aβ peptides (29). These receptors, which are members of the immunoglobulin superfamily, are found in dendritic cells. These cells are known to “travel” between brain and lymph nodes (30).

Because of the presence of Aβ peptides in the interstitial cerebral fluid, several investigators have also proposed that Aβ peptides might be drained into peripheral lymph nodes (31-33). However, except for our prior paper (12) and the data presented here, there is no additional experimental evidence published about Aβ being cleared into peripheral lymph nodes. A caveat of this investigation is the possibility of Aβ being produced in the lymph nodes themselves. However, the fact that the Prnp promoter drives the expression of the transgene in the brain, such possibility is extremely unlikely. In addition, Aβ was absent in control splenic lymphoid tissue from the same transgenic mice further reinforcing the concept of Aβ lymphatic clearance.

The routes of Aβ elimination through the lymphatic system are not yet fully known. The existence of a “glymphatic clearance pathway” has been proposed (31, 34), although brain derived Aβ peptide has not been traced directly to peripheral lymph nodes (except for our mentioned previous study).

In the last few years, several genes that associate with increased risk of AD have been discovered. Because the products of some of these genes are involved in immune functions, the study of the lymphatic system highlights a new perspective in AD pathogenesis. In fact, one recent study has shown that stimulation of the innate immune system can reduce both Aβ and tau pathology, consistent with this being an important therapeutic target (35). Consequently, the role of the peripheral lymphatic system in AD warrants a fresh reassessment of our conventional thinking. We propose that different biological insults may lead to dysfunction of the lymphatic system (i.e., viral infections or viral reactivation, age related immune-dysfunctions, hormonal deficiencies, among several others) and may contribute to amyloid accumulation in sporadic AD. Numerous inhibitors of Aβ aggregation have been developed in the last 2 decades. However, melatonin may be of importance because it is the only physiologic inhibitor which also shows profound decreases in AD compared to age matched individuals (36). Because melatonin inhibits only the early stages of Aβ aggregation (nucleation phase) and it does not reverse oligomers or fibrils once they have formed, the findings may have important implications for AD prevention. Since our initial reports two decades ago (13, 14, 37), many peer-reviewed studies have been published, confirming the effects of melatonin on Aβ aggregation and neuroprotection (18, 38). Pineal and retinal melatonin is involved in circadian rhythm regulation, and has several physiological functions including vascular actions, antioxidative and neuroprotective properties (39, 40). Melatonin receptor subtypes appear to be differentially affected in the course of AD (40). Melatonin has also a role on gene expression and alters age-related changes in transcription factors and kinase activation (41). More recently, investigations in transgenic models of amyloidosis showed that reduction of amyloid load in melatonin treated mice occurs only when treatment begins prior to the onset of amyloid accumulation (42).

Melatonin trials conducted in the clinical phase of AD have either failed (43) or show modest positive effects on cognition (44, 45). However, no double blind, placebo control clinical trials using melatonin for AD prevention have ever been conducted. Based on the preclinical data mentioned previously, it is more likely that melatonin will prevent Aβ aggregation rather than reverse the neuropathology in the clinically manifested phases of the disease. However, there is longitudinal neuropsychological data available suggesting that patients afflicted with mild cognitive impairment perform significantly better than it would be expected, when they are treated with melatonin (46). In addition, melatonin experts such as Cardinali et al and others, have pointed to problems with the dosages used in the trials of melatonin in AD conducted that would need to be revisited (47). We hope that this contribution will stimulate further research into this area, including studies of melatonin pharmacokinetics as it applies to lymphatic clearance of Aβ as well as the fate of Aβ in melatonin treated models of AD. Melatonin or its analogs [i.e., indole-3-propionic acid (48, 49)] should be further explored for the prevention of AD in high risk populations.

References

- 1.Glenner GG, Wong CW. Alzheimer's disease and Down's syndrome: sharing of a unique cerebrovascular amyloid fibril protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1984;122(3):1131–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tomiyama T, Nagata T, Shimada H, Teraoka R, Fukushima A, Kanemitsu H, et al. A new amyloid beta variant favoring oligomerization in Alzheimer's-type dementia. Ann Neurol. 2008;63(3):377–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pappolla MA, Omar RA, Kim KS, Robakis NK. Immunohistochemical evidence of oxidative [corrected] stress in Alzheimer's disease. The American journal of pathology. 1992;140(3):621–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pappolla MA, Chyan YJ, Omar RA, Hsiao K, Perry G, Smith MA, et al. Evidence of oxidative stress and in vivo neurotoxicity of beta-amyloid in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer's disease: a chronic oxidative paradigm for testing antioxidant therapies in vivo. The American journal of pathology. 1998;152(4):871–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith MA, Hirai K, Hsiao K, Pappolla MA, Harris PL, Siedlak SL, et al. Amyloid-beta deposition in Alzheimer transgenic mice is associated with oxidative stress. J Neurochem. 1998;70(5):2212–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bozner P, Grishko V, LeDoux SP, Wilson GL, Chyan YC, Pappolla MA. The amyloid beta protein induces oxidative damage of mitochondrial DNA. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1997;56(12):1356–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tai LM, Ghura S, Koster KP, Liakaite V, Maienschein-Cline M, Kanabar P, et al. APOE-modulated Abeta-induced neuroinflammation in Alzheimer's disease: current landscape, novel data, and future perspective. J Neurochem. 2015;133(4):465–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hardy J The amyloid hypothesis for Alzheimer's disease: a critical reappraisal. J Neurochem. 2009;110(4):1129–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baranello RJ, Bharani KL, Padmaraju V, Chopra N, Lahiri DK, Greig NH, et al. Amyloid-beta protein clearance and degradation (ABCD) pathways and their role in Alzheimer's disease. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2015;12(1):32–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koh L, Zakharov A, Johnston M. Integration of the subarachnoid space and lymphatics: is it time to embrace a new concept of cerebrospinal fluid absorption? Cerebrospinal Fluid Res. 2005;2:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hladky SB, Barrand MA. Mechanisms of fluid movement into, through and out of the brain: evaluation of the evidence. Fluids Barriers CNS. 2014;11(1):26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pappolla M, Sambamurti K, Vidal R, Pacheco-Quinto J, Poeggeler B, Matsubara E. Evidence for lymphatic Abeta clearance in Alzheimer's transgenic mice. Neurobiol Dis. 2014;71:215–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pappolla M, Bozner P, Soto C, Shao H, Robakis NK, Zagorski M, et al. Inhibition of Alzheimer beta-fibrillogenesis by melatonin. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1998;273(13):7185–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Poeggeler B, Miravalle L, Zagorski MG, Wisniewski T, Chyan YJ, Zhang Y, et al. Melatonin reverses the profibrillogenic activity of apolipoprotein E4 on the Alzheimer amyloid Abeta peptide. Biochemistry. 2001;40(49):14995–5001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bazoti FN, Tsarbopoulos A, Markides KE, Bergquist J. Study of the non-covalent interaction between amyloid-beta-peptide and melatonin using electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. J Mass Spectrom. 2005;40(2):182–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Galanakis PA, Bazoti FN, Bergquist J, Markides K, Spyroulias GA, Tsarbopoulos A. Study of the interaction between the amyloid beta peptide (1-40) and antioxidant compounds by nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Biopolymers. 2011;96(3):316–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kirschner DA, Gross AA, Hidalgo MM, Inouye H, Gleason KA, Abdelsayed GA, et al. Fiber diffraction as a screen for amyloid inhibitors. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2008;5(3):288–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheng X, van Breemen RB. Mass spectrometry-based screening for inhibitors of beta-amyloid protein aggregation. Anal Chem. 2005;77(21):7012–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bondy SC, Yang YE, Walsh TJ, Gie YW, Lahiri DK. Dietary modulation of age-related changes in cerebral pro-oxidant status. Neurochemistry international. 2002;40(2):123–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lahiri DK, Chen D, Ge YW, Bondy SC, Sharman EH. Dietary supplementation with melatonin reduces levels of amyloid beta-peptides in the murine cerebral cortex. Journal of pineal research. 2004;36(4):224–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cernysiov V, Gerasimcik N, Mauricas M, Girkontaite I. Regulation of T-cell-independent and T-cell-dependent antibody production by circadian rhythm and melatonin. Int Immunol. 2010;22(1):25–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carrillo-Vico A, Guerrero JM, Lardone PJ, Reiter RJ. A review of the multiple actions of melatonin on the immune system. Endocrine. 2005;27(2):189–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hsiao K, Chapman P, Nilsen S, Eckman C, Harigaya Y, Younkin S, et al. Correlative memory deficits, Abeta elevation, and amyloid plaques in transgenic mice. Science. 1996;274(5284):99–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Asami-Odaka A, Ishibashi Y, Kikuchi T, Kitada C, Suzuki N. Long amyloid beta-protein secreted from wild-type human neuroblastoma IMR-32 cells. Biochemistry. 1995;34(32):10272–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matsubara E, Ghiso J, Frangione B, Amari M, Tomidokoro Y, Ikeda Y, et al. Lipoprotein-free amyloidogenic peptides in plasma are elevated in patients with sporadic Alzheimer's disease and Down's syndrome. Ann Neurol. 1999;45(4):537–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suzuki N, Cheung TT, Cai XD, Odaka A, Otvos L Jr., Eckman C, et al. An increased percentage of long amyloid beta protein secreted by familial amyloid beta protein precursor (beta APP717) mutants. Science. 1994;264(5163):1336–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takamura A, Kawarabayashi T, Yokoseki T, Shibata M, Morishima-Kawashima M, Saito Y, et al. Dissociation of beta-amyloid from lipoprotein in cerebrospinal fluid from Alzheimer's disease accelerates beta-amyloid-42 assembly. J Neurosci Res. 2011;89(6):815–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Takamura A, Okamoto Y, Kawarabayashi T, Yokoseki T, Shibata M, Mouri A, et al. Extracellular and intraneuronal HMW-AbetaOs represent a molecular basis of memory loss in Alzheimer's disease model mouse. Mol Neurodegener. 2011;6(1):20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim T, Vidal GS, Djurisic M, William CM, Birnbaum ME, Garcia KC, et al. Human LilrB2 is a beta-amyloid receptor and its murine homolog PirB regulates synaptic plasticity in an Alzheimer's model. Science. 2013;341(6152):1399–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hatterer E, Touret M, Belin MF, Honnorat J, Nataf S. Cerebrospinal fluid dendritic cells infiltrate the brain parenchyma and target the cervical lymph nodes under neuroinflammatory conditions. PLoS One. 2008;3(10):e3321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Iliff JJ, Wang M, Liao Y, Plogg BA, Peng W, Gundersen GA, et al. A paravascular pathway facilitates CSF flow through the brain parenchyma and the clearance of interstitial solutes, including amyloid beta. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4(147):147ra11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weller RO, Massey A, Newman TA, Hutchings M, Kuo YM, Roher AE. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy: amyloid beta accumulates in putative interstitial fluid drainage pathways in Alzheimer's disease. Am J Pathol. 1998;153(3):725–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tarasoff-Conway JM, Carare RO, Osorio RS, Glodzik L, Butler T, Fieremans E, et al. Clearance systems in the brain--implications for Alzheimer diseaser. Nature reviews Neurology. 2016;12(4):248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Neuroscience Nedergaard M.. Garbage truck of the brain. Science. 2013;340(6140):1529–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scholtzova H, Chianchiano P, Pan J, Sun Y, Goni F, Mehta PD, et al. Amyloid beta and Tau Alzheimer's disease related pathology is reduced by Toll-like receptor 9 stimulation. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2014;2:101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu YH, Feenstra MG, Zhou JN, Liu RY, Torano JS, Van Kan HJ, et al. Molecular changes underlying reduced pineal melatonin levels in Alzheimer disease: alterations in preclinical and clinical stages. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(12):5898–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pappolla MA, Chyan YJ, Poeggeler B, Bozner P, Ghiso J, LeDoux SP, et al. Alzheimer beta protein mediated oxidative damage of mitochondrial DNA: prevention by melatonin. Journal of pineal research. 1999;27(4):226–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.He H, Dong W, Huang F. Anti-amyloidogenic and anti-apoptotic role of melatonin in Alzheimer disease. Current neuropharmacology. 2010;8(3):211–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pappolla MA, Sos M, Omar RA, Bick RJ, Hickson-Bick DL, Reiter RJ, et al. Melatonin prevents death of neuroblastoma cells exposed to the Alzheimer amyloid peptide. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 1997;17(5):1683–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Savaskan E, Jockers R, Ayoub M, Angeloni D, Fraschini F, Flammer J, et al. The MT2 melatonin receptor subtype is present in human retina and decreases in Alzheimer's disease. Current Alzheimer research. 2007;4(1):47–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bondy SC, Li H, Zhou J, Wu M, Bailey JA, Lahiri DK. Melatonin alters age-related changes in transcription factors and kinase activation. Neurochemical research. 2010;35(12):2035–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.O'Neal-Moffitt G, Delic V, Bradshaw PC, Olcese J. Prophylactic melatonin significantly reduces Alzheimer's neuropathology and associated cognitive deficits independent of antioxidant pathways in AbetaPP(swe)/PS1 mice. Molecular neurodegeneration. 2015;10:27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Singer C, Tractenberg RE, Kaye J, Schafer K, Gamst A, Grundman M, et al. A multicenter, placebo-controlled trial of melatonin for sleep disturbance in Alzheimer's disease. Sleep. 2003;26(7):893–901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wade AG, Farmer M, Harari G, Fund N, Laudon M, Nir T, et al. Add-on prolonged-release melatonin for cognitive function and sleep in mild to moderate Alzheimer's disease: a 6-month, randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial. Clinical interventions in aging. 2014;9:947–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Asayama K, Yamadera H, Ito T, Suzuki H, Kudo Y, Endo S. Double blind study of melatonin effects on the sleep-wake rhythm, cognitive and non-cognitive functions in Alzheimer type dementia. Journal of Nippon Medical School = Nippon Ika Daigaku zasshi. 2003;70(4):334–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cardinali DP, Vigo DE, Olivar N, Vidal MF, Furio AM, Brusco LI. Therapeutic application of melatonin in mild cognitive impairment. American journal of neurodegenerative disease. 2012;1(3):280–91. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cardinali DP, Vigo DE, Olivar N, Vidal MF, Brusco LI. Melatonin Therapy in Patients with Alzheimer's Disease. Antioxidants (Basel, Switzerland). 2014;3(2):245–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chyan YJ, Poeggeler B, Omar RA, Chain DG, Frangione B, Ghiso J, et al. Potent neuroprotective properties against the Alzheimer beta-amyloid by an endogenous melatonin-related indole structure, indole-3-propionic acid. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1999;274(31):21937–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Poeggeler B, Sambamurti K, Siedlak SL, Perry G, Smith MA, Pappolla MA. A novel endogenous indole protects rodent mitochondria and extends rotifer lifespan. PLoS One. 2010;5(4):e10206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]