Executive summary

The story of dying in the 21st century is a story of paradox. While many people are overtreated in hospitals with families and communities relegated to the margins, still more remain undertreated, dying of preventable conditions and without access to basic pain relief. The unbalanced and contradictory picture of death and dying is the basis for this Commission.

How people die has changed radically over recent generations. Death comes later in life for many and dying is often prolonged. Death and dying have moved from a family and community setting to primarily the domain of health systems. Futile or potentially inappropriate treatment can continue into the last hours of life. The roles of families and communities have receded as death and dying have become unfamiliar and skills, traditions, and knowledge are lost. Death and dying have become unbalanced in high-income countries, and increasingly in low-and-middle-income countries; there is an excessive focus on clinical interventions at the end of life, to the detriment of broader inputs and contributions.

The COVID-19 pandemic has meant that death is prominent in daily media reports and health systems have been overwhelmed. People have died the ultimate medicalised deaths, often alone but for masked staff in hospitals and intensive care units, unable to communicate with family except electronically. This situation has further fuelled the fear of death, reinforcing the idea of health-care services as the custodian of death.

Climate change, the COVID-19 pandemic, environmental destruction, and attitudes to death in high-income countries have similar roots—our delusion that we are in control of, and not part of, nature. Large sums are being invested to dramatically extend life, even achieve immortality, for a small minority in a world that struggles to support its current population. Health care and individuals appear to struggle to accept the inevitability of death.

Philosophers and theologians from around the globe have recognised the value that death holds for human life. Death and life are bound together: without death there would be no life. Death allows new ideas and new ways. Death also reminds us of our fragility and sameness: we all die. Caring for the dying is a gift, as some philosophers and many carers, both lay and professional, have recognised. Much of the value of death is no longer recognised in the modern world, but rediscovering this value can help care at the end of life and enhance living.

Treatment in the last months of life is costly and a cause of families falling into poverty in countries without universal health coverage. In high-income countries between 8% and 11·2% of annual health expenditure for the entire population is spent on the less than 1% who die in that year. Some of this high expenditure is justified, but there is evidence that patients and health professionals hope for better outcomes than are likely, meaning treatment that is intended to be curative often continues for too long.

Conversations about death and dying can be difficult. Doctors, patients, or family members may find it easier to avoid them altogether and continue treatment, leading to inappropriate treatment at the end of life. Palliative care can provide better outcomes for patients and carers at the end of life, leading to improved quality of life, often at a lower cost, but attempts to influence mainstream health-care services have had limited success and palliative care broadly remains a service-based response to this social concern.

Rebalancing death and dying will depend on changes across death systems—the many inter-related social, cultural, economic, religious, and political factors that determine how death, dying, and bereavement are understood, experienced, and managed. A reductionist, linear approach that fails to recognise the complexity of the death system will not achieve the rebalancing needed. Just as they have during the COVID-19 pandemic, the disadvantaged and powerless suffer most from the imbalance in care when dying and grieving. Income, education, gender, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, and other factors influence how much people suffer in death systems and the capacity they possess to change them.

Radically reimagining a better system for death and dying, the Lancet Commission on the Value of Death has set out the five principles of a realistic utopia: a new vision of how death and dying could be. The five principles are: the social determinants of death, dying, and grieving are tackled; dying is understood to be a relational and spiritual process rather than simply a physiological event; networks of care lead support for people dying, caring, and grieving; conversations and stories about everyday death, dying, and grief become common; and death is recognised as having value.

Systems are constantly changing, and many programmes are underway that encourage the rebalancing of our relationship with death, dying, and grieving. Communities from varied geographies are challenging norms and rules about caring for dying people, and models of citizen and community action, such as compassionate communities, are emerging. Policy and legislation changes are recognising the impact of bereavement and supporting the availability of medication to manage pain when dying. Hospitals are changing their culture to openly acknowledge death and dying; health-care systems are beginning to work in partnership with patients, families, and the public on these issues and to integrate holistic care of the dying throughout health services.

Key messages.

-

•

Dying in the 21st century is a story of paradox. Although many people are overtreated in hospitals, still more remain undertreated, dying of preventable conditions and without access to basic pain relief.

-

•

Death, dying, and grieving today have become unbalanced. Health care is now the context in which many encounter death and as families and communities have been pushed to the margins, their familiarity and confidence in supporting death, dying, and grieving has diminished. Relationships and networks are being replaced by professionals and protocols.

-

•

Climate change, the COVID-19 pandemic, and our wish to defeat death all have their origins in the delusion that we in control of, not part of, nature.

-

•

Rebalancing death and dying will depend on changes across death systems—the many inter-related social, cultural, economic, religious, and political factors that determine how death, dying, and bereavement are understood, experienced, and managed.

-

•

The disadvantaged and powerless suffer most from the imbalance in care for those dying and grieving.

-

•

The Lancet Commission on the Value of Death sets out five principles of a realistic utopia, a new vision of how death and dying could be. The five principles are: the social determinants of death, dying, and grieving are tackled; dying is understood to be a relational and spiritual process rather than simply a physiological event; networks of care lead support for people dying, caring, and grieving; conversations and stories about everyday death, dying, and grief become common; and death is recognised as having value.

-

•

The challenge of transforming how people die and grieve today has been recognised and responded to by many around the world. Communities are reclaiming death, dying and grief as social concerns, restrictive policies on opioid availability are being transformed and health-care professionals are working in partnership with people and families, but more is needed.

-

•

To achieve our ambition to rebalance death, dying and grieving, radical changes across all death systems are needed. It is a responsibility for us all, including global bodies and governments, to take up this challenge. The Commission will continue its work in this area.

These innovations do not yet amount to a whole system change, but something very close to the Commission's realistic utopia has been achieved in Kerala, India, over the past three decades. Death and dying have been reclaimed as a social concern and responsibility through a broad social movement comprised of tens of thousands of volunteers complemented by changes to political, legal, and health systems.

To achieve the ambition of radical change across death systems we present a series of recommendations, outlining the next steps that we urge policy makers, health and social care systems, civil society, and communities to take. Death and dying must be recognised as not only normal, but valuable. Care of the dying and grieving must be rebalanced, and we call on people throughout society to respond to this challenge.

Introduction

“How pathetic it was to try to relegate death to the periphery of life when death was at the centre of everything.”

Elif Shafak, Turkish novelist

The proposition of the Lancet Commission on the Value of Death is that our relationship with death and dying has become unbalanced, and we advocate a rebalancing. At the core of this rebalancing must be relationships and partnerships between people who are dying, families, communities, health and social care systems, and wider civic society.

In high-income countries, death and dying have become unbalanced as they moved from the context of family, community, relationships, and culture to sit within the health-care system. Health care has a role in the care of the dying, but interventions at end of life are often excessive,1, 2 exclude contributions from families and friends,3 increase suffering,4, 5 and consume resources that could otherwise be used to meet other needs.6 This lack of balance in high-income countries is spreading to low-and-middle-income countries, a form of modern colonialism, and the imbalance may be worse in low-and-middle-income countries, as this report will show.

The relationship with death and dying in low-and-middle-income countries is unbalanced as the rich receive excessive care, while the poor, the majority, receive little or no attention or relief of suffering and have no access to opioids, as the Lancet Commission on Global Access to Palliative Care and Pain Relief showed.7 Excessive treatment for the rich and inadequate or absent care for the poor is a paradox and a failing of global health and solidarity.

Readers may wonder about the title of the Commission: the Lancet Commission on the Value of Death. The title has its origins in the Lancet planning a Commission on the value of life. It's an age-old idea that a good life and a good death go together. Our title has proved to be a rich source of thinking, helping us recognise the value of death in a world that tends to deny death any value. The simplest proposition of the value of death is that “without death every birth would be a tragedy”, and in a very crowded world we are the edge of such a tragedy. In the report we explore the many values of death.

The Commission began its work before the COVID-19 pandemic arrived, bringing death to television screens every night. Dying on a ventilator, looked after by masked and gowned staff, and only able to communicate with family through screens, is the ultimate medicalised death. Yet even in high-income countries, many have died at home with minimal support, and in low-and-middle-income countries hundreds of thousands have died with no care from health professionals. The capacity of health services was exceeded in many countries during the course of 2020 and 2021. The Commissioners wondered whether death and dying rising so high on the agenda would change attitudes to death and dying, perhaps bringing greater acceptance of death and a recognition of its imbalanced nature. As 2021 draws to a close, we see no evidence of such a change. Indeed, we see signs of the opposite: governments have prioritised attempts to reduce only the number of deaths and not the amount of suffering; huge emphasis has been placed on ventilators and intensive care and little on palliative care; bereavement has been overlooked; anxiety about death and dying seems to have increased;8, 9 death and dying has come to belong still more to health care, with families and communities excluded; and we hear from Commissioners stories of doctors increasing their efforts to fend off death from causes other than COVID-19. The great success with vaccines has perhaps further fuelled the fantasy that science can defeat death. Scholarly research on changes in attitudes to death and dying is limited at this early stage, but the historian Yuval Noah Harari has asked whether the pandemic will change attitudes to death and dying and what humanity's takeaway will be: “In all likelihood, it will be that we need to invest even more efforts in protecting human lives. We need to have more hospitals, more doctors, more nurses. We need to stockpile more respiratory machines, more protective gear, more testing kits.”10

At the start of the COVID-19 pandemic we thought that perhaps a report on the value of death would not be welcome after millions of deaths, but we now think the opposite—that the pandemic makes our report more relevant, and our recommendations will make us better able to respond to the next pandemic.

Although the pandemic seems not to have encouraged greater acceptance of death, it has been accompanied by a rapid rise in concern about the ecological crisis, including climate change. COP26 (Conference of the Parties), the annual UN meeting on climate change, held in Glasgow in November, 2021, achieved far greater media coverage and stronger commitments to reduce carbon emissions than any previous meeting, although the commitments are not enough to prevent serious harm to health. This increase in concern has various roots, but the pandemic has reminded us that we are part of nature, not in control of nature. The pandemic and the ecological crisis are both caused by our failure to recognise our connection with nature and our destruction of the natural environment. The Commission believes that the drive to fend off death and pursue a dramatic extension in length of life also arises from a failure to recognise that we are part of nature; and as financial cost and carbon consumption are closely related to expensive care, treatment at the end of life will be an important contribution to the carbon footprint of health care. Were it a country, health care would be the world's fifth largest emitter of greenhouse gases.11 Unfortunately, the carbon footprint of most health systems is rising when it needs to fall to net-zero by the middle of the century.12 Panel 1 discusses further the connection between climate change, the ecological crisis, and death and dying.

Panel 1. Death and the climate crisis.

The Covid-19 pandemic has revealed our global interdependence and the fragility of our support systems and economy. The Canadian archeologist and author, Ronald Wright, described how every empire that has ever existed has collapsed, usually for ecological reasons.13 Now, he points out, we are one global empire. The COVID-19 pandemic will pass, like the epidemics before it, but damage to the climate and the planet will be irreparable. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) advises that we have only a dozen years to avoid that damage,14 but carbon emissions are increasing by about 7% annually, not decreasing by 7%, as the IPCC says is necessary.

Everything, and especially death, must be thought of in the context of the climate crisis. Before the pandemic we were on track for a temperature increase of 8·5 degrees Celsius over preindustrial levels, which, as Nature pointed out, would lead us to conditions like that of the Permian extinction event, when some 95% of all life forms were made extinct.15 The IPCC says that global temperature increases must be kept below 1·5°C. Already we are close to an increase of 1·3°C, and the effects are being felt now.

Carbon emissions are a function of the number of humans, currently 7·9 billion, and the carbon they each consume. The average Briton consumes 5·6 metric tons of carbon each year (16·1 tons for Americans), whereas the average Bangladeshi consumes 0·6 metric tons. If the world is to reach net-zero carbon emissions by 2050 then people in rich countries will have to consume much less carbon and shift resources to lower income countries. The UK Health Alliance on Climate Change says that this shift would mean, for example, Britons consuming 0·5 metric tons each year16—a dramatic change, but one that would lead to an improvement in health as people drive less, exercise more, and eat diets low in animal products and high in fruit and vegetables.

Health systems account for a substantial proportion of country's carbon emissions—12% in the USA and 5% in the UK.12 Carbon emissions from health systems are currently increasing,12 although some organisations are attempting to reverse this trend. NHS England has published a detailed plan of how it plans to reach net-zero by 2045.17

The carbon footprint of health systems can be reduced by activities like switching to renewable energy, reducing travel, and redesigning buildings, but it will also mean changing clinical practice. Increasingly the carbon consumption of clinical activity will matter more than the financial cost, and methods exist to capture this consumption.18 This Commission has summarised evidence of excessive treatment at the end of life. We now need to assemble evidence on the carbon cost: while the dead consume no carbon, the disposal of bodies does.

About three quarters of people in Britain are cremated after death, releasing carbon into the air. Alkaline hydrolysis, in which the body is dissolved, has about a seventh of the carbon footprint of cremation, and the resulting fluid can be used as fertiliser. A Dutch study of the disposal of bodies found that the lowest amount of money that it would theoretically cost to compensate in terms of the carbon footprint per body was €63·66 for traditional burial, €48·47 for cremation, and €2·59 for alkaline hydrolysis.19 Composting or natural burial are alternatives.

If we are to survive the climate crisis then almost everything will have to change, including health care, end-of-life care, and how we dispose of the dead. In the widely acclaimed novel Overstory, a eulogy to trees and nature, a leading environmentalist asks the audience at a conference what they can best do to counter climate change and environmental destruction: her answer is, to die.

Structure of the report

Section 1 of the report defines the territory and methods of the Commission, including the limitations and what it has not been possible to cover in this report. Section 2 presents a brief survey of the facts and figures of death and dying in the 21st century.

The Commission recognises that rebalancing death and dying will depend on changes across death systems: the many inter-related social, cultural, economic, religious, and political factors that determine how death, dying, and bereavement are understood, experienced and managed.20 Section 3 describes the concept of a death system.

Sections 4 to 10 describe death systems now, covering philosophical and religious underpinnings; historical origins; the influence of power and inequities; the role of families and communities; consumerism and choice; the dominance of health care; and the importance of economics.

Following this examination of historic and contemporary death systems, in section 11 the Commission uses scenario planning to imagine five different but plausible futures for death and dying.

Section 12 outlines the features of a realistic utopia,21 a concept developed by the American philosopher John Rawls (1921–2002), which shares principles of how the Commissioners would like to see death and dying change in a way that is achievable. It is a radically different future envisioned by the Commission in which life, wellbeing, death, and grieving are in balance.

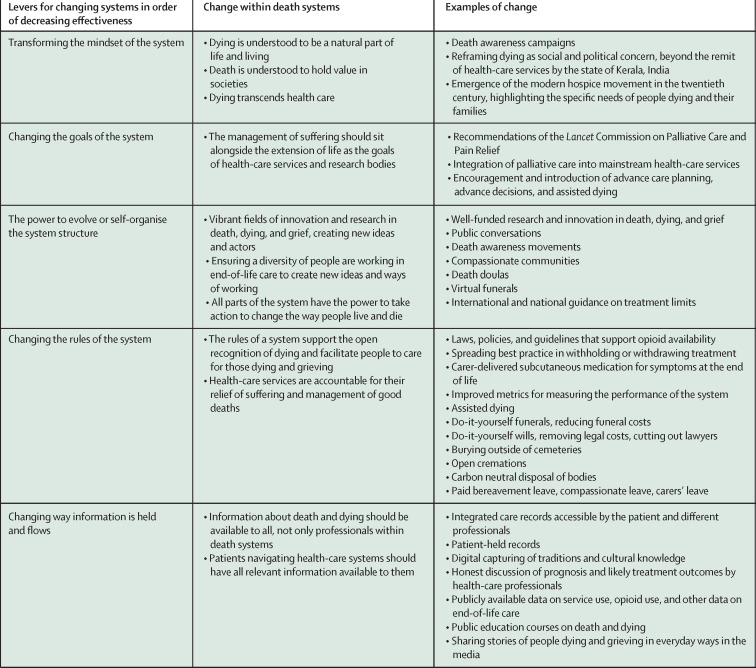

Recognising that creating the “realistic utopia” will depend on many changes within death systems, section 13 discusses why systems are hard to change and how they might be changed. The section also gives examples of changes in systems that are underway.

Section 14 gives a detailed and critical account of the end-of-life system in Kerala, South India, as it represents the system closest to the realistic utopia the Commission has described.

Section 15 lists the Commission's recommendations for change, and the final section, section 16, proposes the next steps the Commission will take to try and achieve this change.

Section 1: Defining our territory and methods

Death can occur through conflict, accident, natural disaster, pandemic, violence, suicide, neglect, or disease, but this Commission focuses particularly on the time from when a person develops a life-limiting illness or injury through their death and into the bereavement affecting the lives of those left behind. We do not address specific diseases, conditions, or age groups, but rather draw on a wide-ranging series of examples to show the depth and breadth of the challenge. These examples are not intended to be systematic or exhaustive but rather illustrative. We draw on a range of different materials from case study and reflection to national datasets and empirical work and have used scoping rather than systematic literature searches.

The Commission has drawn its membership from around the world, but much of the evidence reported on comes from high-income countries. What we describe, both the problems and the possibilities, has relevance for all settings.

The Commissioners (see end of this report] include health and social care professionals, social scientists, health scientists, economists, a philosopher, a political scientist, patients, a carer, religious leaders, activists, community workers, and a novelist.

We acknowledge the diversity of experience in death, dying, and grief and how race, gender, sexuality, poverty, disability, age, and many other potential forms of marginalisation shape experiences and outcomes at these times. The intersectional nature of these aspects of people's lives and identities means marginalisation is rarely due to a single factor. We have attempted to be reflexive as people, Commissioners, and authors, to understand how our own worldviews, cultural backgrounds, identities, professional disciplines, and experiences determine our perspectives and actions. In recognition of the inclusive and reflexive spirit of this report, we endeavour to use terms in their broadest and most inclusive sense throughout. Words such as person, patient, family, carer, illness, community, relationship, and many others should be understood in this context.

We have reflected that we should have done more to include the voice of patients and carers, although all Commissioners brought their own personal experiences of death and bereavement. We are conscious that there are many voices we have not heard, but we see this report as the start of a conversation and hope to hear from further voices after publication.

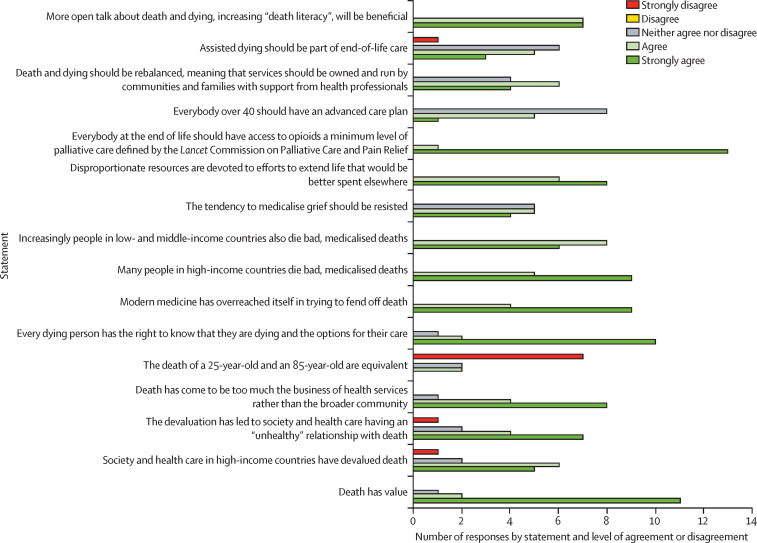

We have chosen the term “health-care professionals” to denote all those working in health-care settings, including doctors, nurses, and allied health professionals, but we acknowledge that there exists an appreciable variation in approach and practice within these groups. We also appreciate the role social care professionals play at the end of life, and the interdependent relation between health and social care in many countries around the world. Over the course of the past 3 years, the Commissioners met together physically three times, held frequent virtual meetings, and communicated regularly by email. We commissioned working papers from other authors and have drawn on many sources of knowledge and understanding. The report has contributors with differing views. We have not sought agreement or conformity in our argument but have attempted to capture the tensions that exist among Commissioners. Figure 1 shows agreements and disagreements on a range of issues, including assisted dying, which we expected to divide Commissioners; there was more agreement than our intense discussions had led us to think.

Figure 1.

Level of agreement and disagreement among commissioners on statements about death and dying

Not all commissioners responded to the survey; 14 commissioners participated.

The Commission has created an open website with more than 70 background papers relating to death and dying. Much of what is included in our report is rewritten and condensed versions of those entries. The report has been through five major restructurings, two of them after the first round of editorial and peer review. Death and dying are distinct, multi-layered, and culturally charged concepts. Death can be seen as simply the end of life; as the opposite of health—although the Commission believes that it is healthy to die; as a symbol, classically a skeleton or a grim reaper; as a failure (and many would argue that doctors or health-care professionals can see death as a failure, inspiring them to do all they can to defeat death); as a punishment for moral failure; as an escape from the suffering of life; as a gateway to Heaven, Valhalla, Nirvana, or the many other religious and cultural depictions of eternal bliss or to a version of Hell; or as an essential part of a cycle of ending and beginning.

The Commission has generally been narrower in its use of the words death and dying. We see dying as a process. We have not set a timeframe, understanding that people may be dying for years, months, days, hours, minutes, or seconds. We understand death as an event but with recent changes in technology, failing organs that previously heralded death can be replaced, meaning that death is an evolving and complex concept. Only within the past decade did an international consensus attempt to define how death is determined.22

Defining death

In 2014, WHO convened the second meeting of a task force on the determination of death,23 acknowledging that the line between life and death was being increasingly blurred by medical technology. It concluded that although there are multiple ways to die, including neurological and cardiovascular pathways, they all lead to the same irreversible state of being dead. As a result, the algorithms of circulatory and neurological death were merged, with a single endpoint. The definition of death relies on certain clinical signs such as absence of a response, pulse, breathing, and pupillary reflexes.

The WHO guidance relates to death in medical institutions or under professional care and is based on clinical signs interpreted by professionals. A large proportion of deaths around the world take place outside clinical oversight, and the signs and symptoms are interpreted by lay people with experience of death and dying. The recognition of death is often linked with the traditions, rituals, and funeral practices of the particular culture.24 Panel 2 describes how in places in rural Malawi, the village elders and then the village head's representative confirm death. The head's signal that a death has occurred starts the vigil and mourning process.

Panel 2. Lay determination of death in Malawi.

Luckson Dullie, member of the Commission, writes:

In rural Malawi death is confirmed by the elders. There is no exact checklist, but experience from having witnessed so many deaths has taught them that dying people lose weight fast; their strength fails; they speak little or incomprehensibly; and their breath is often shallow and laboured. The elders know that often dying people do not want to look you in the face, or when they do, their face is blank, empty, because the spirit has already departed. When they think death has occurred, the elders feel for the pulse in the neck, but the most tell-tale sign is cold armpits. The process of confirmation of death can take 2 hours or longer. During this time, the elders must ensure that the body lies straight and that the mouth and the eyes are closed. Children are not allowed in the room. Once death is confirmed, a message must be dispatched to the village head. Until the village head is told and they or their representative confirms the death, no one is allowed to cry out loud. The village head's confirmation signals the start of vigil and mourning process.

Section 2: The facts and figures of death and dying in the 21st century

At first sight, mortality trends over the past 30 years suggest a success story. Global life expectancy has risen steadily throughout the world, increasing from 67·2 years in 2000 to 73·5 years in 2019,25 with important gains made in low-and-middle-income countries. This success has been driven by falls in deaths from communicable disease, maternal and neonatal conditions, and malnutrition.26 But healthy life expectancy (years lived in self-reported good health) has not kept pace with overall life expectancy: years lived without good health have increased between 2000 and 2019—from 8·6 years to 10 years.25

In many high-income countries in the past decade, life expectancy gains have stalled, or in some cases reversed. In the UK, life expectancy increases slowed from 2011 to 2020 and fell for women in the most deprived 10% of neighbourhoods.27 In the USA, life expectancy fell from 1990 to 2000 for women with fewer than 12 years of formal education28 Life expectancy in the USA has also fallen in younger age groups (10–65 years), probably reflecting the opioid epidemic.29 As 2021 closes, the COVID-19 pandemic is far from over, particularly in low-and-middle-income countries. The pandemic's effects on life expectancy are not complete and have not yet been measured in most countries—but reductions are likely to be more than a year in most countries. Data are available for the USA, where life expectancy fell by 1·87 years (to 76·87 years) between 2018 and 2020. The reductions have been very unequal, with life expectancy falling by 3·88 years among Hispanic people, 3·25 years among non-Hispanic Black people, and 1·36 years among non-Hispanic White people.30 In England, life expectancy has fallen from 80 years for males and 83·7 years for females in 2019 to 78·7 years for males and 82·7 years for females in 2020, a similar level to a decade ago.31 As in the USA, the reductions have been greatest among those who are deprived.32

As deaths from infection and maternal and perinatal causes fall in many low-and-middle-income countries, the proportion of deaths from non-communicable disease rises. In Bangladesh, non-communicable disease accounted for 10% of deaths in 1986, but more than three-quarters by 2006, a very rapid transition.33 This change presents new challenges for already stretched health services. Cure for non-communicable disease is not possible, and instead interventions must focus on prevention, harm reduction, and self-management, acknowledging the complex social determinants of these chronic conditions.

Table 1 shows the mortality rates, life expectancy, causes of death, serious health-related suffering, and degree of inequality for seven selected countries represented by the Commissioners. The countries range from high-income to low-income. It illustrates the differences that persist among countries despite global trends. Life expectancy in Malawi is two decades less than that in the UK. Deaths from infection, maternal and perinatal causes, and malnutrition account for 4% of deaths in China but 26% in India and 60% in Malawi. Hundreds of thousands of deaths annually are associated with serious health-related suffering (as defined by the Lancet Commission on Global Access to Palliative Care and Pain Relief7, 40).

Table 1.

Mortality, life expectancy, causes of death, health related suffering, and degree of inequality for seven selected countries represented on the Commission

| Crude death rate per 1000 (2019)34 |

Life expectancy, years (2019)34 |

Income inequality, based on coefficient (2020)35 | Probability of dying aged 15–60 years (per 100; 2019)34 | Under 5 mortality (deaths per 1000 livebirths; 2019)34 | Maternal mortality (per 100 000 livebirths; 2019)36 | Deaths from communicable diseases and maternal, prenatal, and nutrition conditions (% of total; 2016)37 | Deaths from non-communicable disease (% of total; 2016)38 | Age-standardised death rate from suicide (per 100 000; 2016)39 | Deaths associated with serious health-related suffering*(thousands; 2015)40 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Men | Women | ||||||||||

| High income | ||||||||||||

| UK | 9·4 | 81·3 | 79·6 | 84·7 | 32·4% | 6·8 | 4 | 7 | 8% | 89% | 7·6 | 317 |

| USA | 8·8 | 78·9 | 76·3 | 81·4 | 45% | 11·2 | 7 | 19 | 5% | 88% | 13·7 | 1310 |

| Middle income | ||||||||||||

| China | 7·3 | 76·9 | 74·8 | 79·2 | 46·5% | 7·9 | 11 | 29 | 4% | 89% | 8 | 5501 |

| India | 7·3 | 69·7 | 68·5 | 71 | 35·2% | 17·9 | 37 | 145 | 26% | 63% | 16·5 | 3983 |

| Mexico | 6·1 | 75·1 | 72·2 | 77·9 | 48·2% | 14 | 15 | 33 | 10% | 80% | 5·2 | 229 |

| Low income | ||||||||||||

| Malawi | 6·5 | 64·3 | 61·1 | 67·4 | 46·1% | 27·4 | 51 | 349 | 60% | 32% | 7·8 | 78 |

| Bangladesh | 5·5 | 72·6 | 70·9 | 74·6 | 32·1% | 13·6 | 30 | 173 | 26% | 67% | 6·1 | 409 |

Population estimated to be experiencing serious health-related suffering and in need of palliative care based on 20 conditions. Total deaths are weighted by a conversion factor or multiplier for each condition based on review by a panel of experts who deliberated on different considerations and incorporated published evidence as well as their own experience as providers of palliative care. The conditions considered were: atherosclerosis, cerebrovascular disease, chronic ischaemic heart disease, congenital malformations, degeneration of the central nervous system, dementia, diseases of the liver, haemorrhagic fevers, HIV, inflammatory disease of the central nervous system, injury, poisoning, and external causes, leukaemia, lung diseases, malignant neoplasms, musculoskeletal disorders, non-ischaemic heart diseases, premature birth and birth trauma, protein energy malnutrition, renal failure, and tuberculosis.

Table 2 shows how deaths in most high-income and middle-income countries occur more often in hospitals or other institutions, such as nursing or care homes. Limited data are available for low-income countries. The shift from home to institutions is relatively recent, often occurring over the past generation.

Table 2.

Place of death, health-care use, and hospital expenditures at the end of life in different countries

|

Place of death for diseases associated with palliative care need41* |

Inpatient health-care use in last 30 days of life for decedents of any age with any cancer42† | Health expenditures in last 30 days of life for decedents with cancer42‡ | Health expenditures in last 180 days of life for decedents with cancer42‡ | Health expenditures in last 30 days of life as % of health expenditures in last 180 days of life for decedents with cancer42 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Home | Hospital | Long-term care institution | Primary care institution | Other institution or other | |||||

| High income | |||||||||

| Belgium | 24·8% | 50·8% | 23·8% | § | 0·6% | 14 455 (52·9%) | 6206 (6929) | 17 022 (17 642) | 36% |

| Canada | 12·9% | 61·4% | 20·8% | § | 4·8% | 16 917 (60·2%) | 10 843 (13 710) | 23 333 (28 922) | 46% |

| Czech Republic | 18·4% | 64·0% | 16·8% | § | 0·8% | § | § | § | § |

| France | 22·3% | 63·9% | 11·0% | § | 2·8% | § | § | § | § |

| Germany | § | § | § | § | § | 14 468 (47·8%) | 3326 (4394) | 10 033 (9858) | 33% |

| Hungary | § | 66·2% | .. | § | 33·8% | § | § | § | § |

| Italy | 44·4% | 45·7% | 6·1% | § | 3·8% | § | § | § | § |

| Netherlands | 34·5% | 24·6% | 34·5% | § | 6·4% | 3155 (43·7%) | 4766 (9653) | 18 414 (28 673) | 26% |

| New Zealand | 22·5% | 28·1% | 33·4% | 13·0% | 3·0% | § | § | § | § |

| Norway | .. | .. | .. | § | .. | 7052 (63·9%) | 3646 (7227) | 11 640 (14 398) | 31% |

| Spain (Andalusia)¶ | 35·1% | 57·3% | 7·3% | § | 0·3% | § | § | § | § |

| South Korea (Republic of Korea) | 13·5% | 84·9% | 1·3% | § | 0·3% | § | § | § | § |

| UK (England) | 21·7% | 47·5% | 17·8% | 11·6% | 1·3% | 65 616 (50·8%) | 6934 (6842) | 22 005 (20 920) | 32% |

| UK (Wales) | 21·2% | 58·6% | 12·0% | 6·5% | 1·7% | § | § | § | § |

| USA¶ | 31·5% | 37·8% | 22·0% | 3·8% | 5·0% | § | § | § | § |

| Middle income | |||||||||

| Mexico | 53·0% | 44·4% | § | § | 2·7% | § | § | § | § |

Based on death certificate data for 2008; population estimated to be in need of palliative care on the basis of ten conditions: cancer, renal failure, liver failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diseases of the nervous system (Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, motor neurone disease, Huntington's disease), and HIV/AIDS.

Hospitalisation in acute care hospital, number (%).

Mean (SD) per-capita hospital expenditures in US$ (2010; 2011 health-specific purchasing power parity conversion).

Data not available.

Reference year for place of death of patients with cancer: USA 2007, Spain (Andalusia) 2010.

Panel 3 contrasts two deaths in India: one a sudden death in India two generations ago with the whole family, including the children, gathering around the dead man in the family home and taking part in rituals; whereas the modern death is slow and distressing and occurs in intensive care, with even the man's son unable to visit.

Panel 3. Dying now and years ago in India.

M R Rajagopal, member of the Commission, writes:

When I recently saw a doctor-colleague facing the impending death of his son-in-law from cancer, the transformation that happened in our society over two generations became obvious to me.

The most striking memory is the expression of the dying man's 15-year-old son, who was walking in the background choosing books and cramming them into bags. He was not part of the conversation; when he came close the conversation flagged. He was being given an unspoken message: “This is grown-up talk; kids are not part of it”. He responded by pretending not to. He was being sent away to live with an uncle so that his father's illness and death would not disturb his studies.

From two generations back I remember the sudden death of my uncle when I was a child. He was in his late twenties. Nobody knew what ailed him. He just collapsed and died. My grandmother woke me in the middle of the night and carried me 5 km to my dead uncle's home. When I woke in the morning the extended family from far and near had assembled. No one was excluded. We children were part of everything that happened. Every family member had more than one opportunity to touch the dead man. People cried, the grieving women who were close relatives wailed loudly.

For the next 16 days many relatives stayed on all through the day. Their number dwindled as days passed. The more distant relatives left after cremation but returned for the fifth day and 16th day ceremonies. The closer family were throughout. The extended family took over all the expenses of that household during the 16 days following death. Those were the years closely following India's independence from colonial rule; poverty was extreme. But somehow, the extended family members scraped together enough. Women from the extended family took over the kitchen preparing and serving everyone simple meals and looking after all the children.

As I was growing up, I saw many more deaths. The elders in the society oversaw dying, empowered by having seen many deaths—how the limbs got cold, how the rattling in the throat became obvious, and how the pattern of breathing changed. Without anyone teaching anything in a classroom, younger generations took in lessons.

But by no means was death invariably benevolent and beautiful. When the physical suffering in people with diseases like cancer was extreme, no philosophising, compassion, or companionship helped enough. The suffering was excruciating. People just stood watching helplessly. The village physician, who practised Ayurveda, would visit but had little to offer. But the fact that he called helped enormously. The dying person and the family members were never alone in their suffering or grief.

Those deaths of years ago contrast starkly with the death of my colleague's son-in-law. A normal dying process was stretched out over weeks by interventions including an endotracheal tube and artificial ventilation of his lungs (but no pain relief). At the height of his suffering, he tried to pull out the tubes and cables, but his arms and legs were bound to the bed. His wife and father-in-law could visit him for only 5 minutes a couple of times a day, and each time had to watch the man dying a thousand deaths, his dignity and personhood violated in the worst possible way. Eventually, when the doctors suggested a tracheotomy and total parenteral nutrition, the family said no. The man died without seeing his son one last time, and the son was denied one last hug.

Table 2 also provides details of health spending in the last year of life. Health-care expenditure is known to be high and to increase during the last year of a person's life in many countries. These data describe health spending in six high-income countries in the last 6 months of life and demonstrate that costs in the last 30 days before death were disproportionately high compared with those in the 6 months before death.

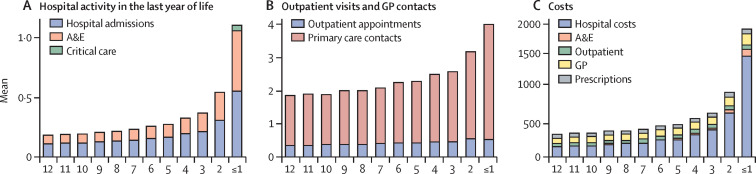

Figure 2 shows use of health services in the last year of life in England, with a steady increase across the year in hospital admissions and visits to the accident and emergency department, with a particularly dramatic increase in the last month of life.43 It is also in the last month that there are admissions to intensive care. It is questionable whether these increases in the last month of life provide benefit for patients and their families, or whether they may in fact be increasing suffering. Costs also increase across the year, with again a dramatic increase in the last month. Most of the costs arise from hospital care. The authors of the study also note that “healthcare utilisation and costs decrease with age at death, and are higher in men, patients dying from cancer, and patients with high comorbidities.”43

Figure 2.

Health-care use and costs in the last 12 months of life

(A) Use of inpatient care. (B) Primary and hospital outpatient care. (C) Total costs by cost type. A&E=accident and emergency department. GP=general practitioner. Reproduced from Luta and colleagues by permission of BMJ Publishing Group.43

Further studies, which the report summarises in the section on the economics of death systems, support the trend of substantially increased health spending in the last weeks of life. Some studies judge the treatments to be futile—for example, artificial nutrition for dying patients,44 chemotherapy in the last 30 days of life,4 or antimicrobial therapy at the end of life.2 Overtreatment at the end of life is part of the broader and pervasive challenge of overuse of medical services, defined as the provision of services likely to produce more harm than good.6

Experiences of dying today

“I came into it [caring for someone dying at home] not knowing you could care for somebody at home but she was dying and not dying fast enough for the hospital system and they kept sending her home and taking her back in and then sending her home again because they needed the bed. And it was very distressing and without any knowledge I decided that we could do better and brought her home…I managed to care for Mum until she died at home which was a great experience for everybody, her family and me.”

Carer in Australia45

Death and dying have changed profoundly over the past 70 years in high-income and middle-income countries, and increasingly in low-income countries. The shifting role of family, community, professionals, institutions, the state, and religion has meant that health care is now the main context in which many people encounter death. People may be unaware that alternatives are possible, as the quote above illustrates. Within this acute health-care setting, death and dying are seen as clinical problems and reduced to a series of separate biomedical markers and tests. Recognition of dying is often made late, if at all, and interventions can continue into the last days of life with minimal attention to suffering.46

As health care has moved to occupy the centre stage, families and communities have been pushed back. Death is not so much denied but invisible. Dying people are whisked away to hospitals or hospices, and whereas two generations ago most children would have seen a dead body, people may now be in their 40s or 50s without ever seeing a dead person. The language, knowledge, and confidence to support and manage dying are being lost, further fuelling a dependence on health-care services. The social and cultural setting of death, essential for providing meaning, connection, and lifelong support for those grieving, risks disappearing. Health-care professionals cannot substitute for the sense of coherence, the rituals and traditions, nor long-term mutual support that families and communities bring to people who are dying or grieving. “The experiment of making mortality a medical experience is just decades old. It is young. And the evidence is it is failing”, writes the surgeon Atul Gawande in his book Being Mortal.46

The impact of a stripped-back, atomised death and bereavement has been seen during the COVID-19 pandemic. People have died alone and families have been unable to say goodbye and prevented from coming together in grief. The effects of this situation will resonate for years to come.

Table 3, which is adapted from the work of the sociologist Lyn Lofland, presents a summary of the shifting trends in death and dying over the past 70 years.47 Defining death has become progressively more complex,23 and the technology accompanying death more sophisticated. Deaths from chronic disease have come to predominate with the consequence that dying takes weeks, months, or years. As the familiarity with death and dying has diminished, countries have witnessed a growth in movements aiming to increase awareness or control over the dying process. We have, argues Lofland, entered an age of “thanatological chic”.47

Table 3.

The changing nature of death and dying (adapted from Lofland)47

| Before 1950 | 1950 | 2019 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Level of medical technology | Low | Increasing | High and increasing |

| Detection of terminal disease | Poor | Improving | High |

| Definition of death | Simple | Still simple | Complex |

| Deaths from acute disease (mostly rapid) | High | Still high | Low |

| Deaths from injuries (mostly rapid) | High | Still high | Lower |

| Deaths from chronic disease (mostly slow) | Low | Increasing | The majority |

| Length of dying | Short | Still mostly short | Long |

| Passivity in response to a person dying | Common | Decreasing | Gone in western medicine |

| Involvement of doctors in dying | Low | Increasing | High |

| Number of doctors in UK per 100 000 people | Fewer than 26 | 26 | 280 |

| Familiarity with death among the population | High | Still high | Low |

| Activities to manage death (death awareness campaigns, advance care planning, assisted dying, etc) | Low | Low | High |

| Community involvement in death and dying | High | Falling | Low |

| Meaning in death and dying | Mostly supplied through faith and faith organisations | Faith and faith organisations still have an important role | Inadequately supplied by multiple organisations, including the health system |

A striking inconsistency with the progressive medicalisation of death and dying is that it has not led to a parallel increase in relief of symptoms such as pain with low-cost, evidence-based methods, nor has it led to universal access to palliative care services at the end of life. Although some countries have established palliative care services, WHO estimates that globally only 14% of people in need can access such care.48 The Lancet Commission on Pain Relief and Palliative Care exposed the stark global inequities in access to opioids.7 Increases in clinical interventions, technology, and institutional care have not reduced—and may have increased—global suffering.

The story of dying in the 21st century is a story of paradox. While many people are overtreated in hospitals, with families and communities relegated to the margins, still more remain undertreated, dying of preventable conditions and without access to basic pain relief. The unbalanced and contradictory picture of death and dying today is the basis for this Commission.

Section 3: Death systems

Hospitals may be the site of dying for many people in the 21st century, but the fault for the unbalanced nature of death and dying does not rest solely with health-care services. Death and dying are intrinsic parts of life. Societies have long sought to understand and provide meaning to these universal events. The cultural anthropologist and psychoanalyst Ernest Becker (1924–74) argued in his Pulitzer-prize-winning book The Denial of Death that fear of death is the dominant driver of culture, religion, art, and human behaviour.49 The wider sociocultural, political, and economic context determines how, where, and why people die and grieve.

Robert Kastenbaum first described the concept of a death system as “interpersonal, socio-physical and symbolic networks through which an individual's relationship to mortality is mediated by society”20 Death systems are the means by which death and dying are understood, regulated, and managed. These systems implicitly or explicitly determine where people die, how people dying and their families should behave, how bodies are disposed of, how people mourn, and what death means for that culture or community. Systems are shaped by social, cultural, religious, economic, and political contexts and evolve over time. One culture's death system can seem strange and even abhorrent to people from other systems.50

Panel 4 describes some of the components of death systems—for example, people, places, and symbols—and panel 5 describes the functions of the system, including, for example, caring for the dying and making sense of death.

Panel 4. Components of the death system (adapted from Kastenbaum)20.

People

Doctors, nurses, police, funeral workers, florists, coroners, life insurance brokers, lawyers, soldiers, religious leaders; ultimately all people will be affected by death and all will die

Places

Mortuaries, hospitals, memorials, cemeteries, battlefields

Times

Annual remembrance days such as the Day of the Dead in Mexico, All Souls Day in Christianity, Anzac Day in Australia and New Zealand, two-minute silences following disasters, private reflections on anniversaries of deaths

Objects

Coffins, urns, funeral pyres, mourning clothes, obituaries, books relating to death and dying, electric chairs, gallows, guns

Symbols and images

Deities responsible for death or war, rituals such as the last prayers in many religions, wearing of black armbands, language and euphemisms for dying, images of skull and crossbones, skeletons

Panel 5. Functions of the death system (adapted from Kastenbaum)20.

Warning and predicting death

Public health and travel warnings, health and safety regulations, extreme weather warnings, climate change predictions

Preventing death

Services such as the police and firefighters, scientists researching vaccines and cures for diseases, screening programmes for disease

Caring for dying people

Practices that support those dying, including practices of family carers, primary healthcare, hospices and palliative care units, death doulas, religious leaders, hospitals, morphine availability, advance care planning

Disposing of dead people

The tasks all societies must perform in disposing safely of corpses and the rituals and funereal customs that accompany these tasks

Social consolidation after death

Processes that allow families or communities to adjust to the loss; social networks and support, compassionate leave from work, bereavement groups or counselling

Making sense of death

Religious, spiritual, or philosophical reflections on the meaning of death or an afterlife, memorialising

Killing

Norms that dictate when and how killing is socially sanctioned, such as in war, in capital punishment, in assisted dying, or the killing of animals

Kastenbaum was writing from an Anglocentric perspective, but all cultures create death systems. Researchers explored death and dying among the indigenous Sámi people in Northern Scandinavia and concluded that despite differences in core concepts—for example, depending on seasonal changes and relationships rather than calendar time—Kastenbaum's model provides a useful tool for understanding this death system.51 Similarly, a group studying the preparations made for death by rural Chinese elders found that the tasks, rituals, imagery, meaning, and roles resonated broadly with the structure developed by Kastenbaum.52

Understanding complex or so-called wicked problems through a systems lens is an approach increasingly required for understanding and intervening in issues such as obesity,53 homelessness,54 or gender inequality.55 Margaret Chan, the director general of WHO from 2006 to 2017, talked of the need for responses to these complex problems from the “whole-of-government and whole-of-society.”56 People have come to these approaches after realising that more reductionist approaches achieve little.

The death system is one of many complex adaptive systems that exist and intersect throughout societies and include, for example, primary care services, education systems, financial systems, families, and communities. Complex adaptive systems have defining features: most importantly, they do not follow linear causation, nor allow simple solutions to problems.57 They exist in a complex web of interacting personal, social, political, religious, and economic drivers. Attempts to reduce a complex adaptive system to the sum of its linear parts to explain how it works, and how to intervene, will be unsuccessful, as their behaviour is emergent and unpredictable. It is the relationship between parts that offers the most insight into how a complex system functions. They are not closed but have blurred boundaries and interact with their environment and other systems. Systems adapt, change, and evolve over time just as death systems have done. Small interventions or changes at one point can have considerable unintended consequences at another: as the famous metaphor suggests, a butterfly beating its wings in New Mexico can cause a hurricane in China. Complex adaptive systems are often fine-tuned to achieve a specific purpose and have feedback loops that ensure they continue to achieve that purpose. Positive feedback loops can also occur, causing sudden shifts in behaviours or outcomes.

Death systems are unique to societies and cultures, but the trends described in Table 1, Table 2 suggest that patterns are emerging across systems. The increased number of deaths in hospital means that ever fewer people have witnessed or managed a death at home. This lack of experience and confidence causes a positive feedback loop that reinforces a dependence on institutional care of the dying. Medical culture, fear of litigation, and financial incentives contribute to overtreatment at the end of life, further fuelling institutional deaths and the sense that professionals must manage death. Social customs influence the conversations in clinics and in intensive care units, often maintaining the tradition of not discussing death openly. More undiscussed deaths in institutions behind closed doors further reduce social familiarity with and understanding of death and dying.

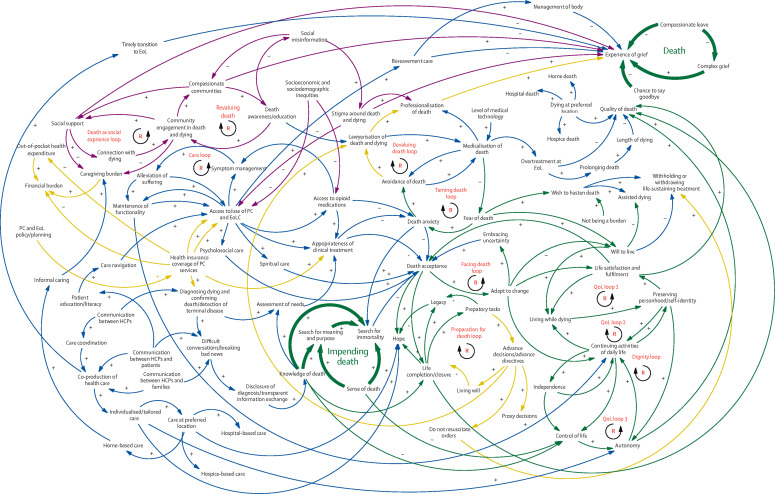

Figure 3 represents one illustration of an aspect of a death system, the end-of-life care system, capturing the complexity, the non-linearity, and the existence of positive and negative feedback loops. The end-of-life system is mapped in a causal loop diagram to show its non-linear and dynamic nature with reinforcing and balancing feedback loops. Arrows track interactions among variables, with polarity noted by plus and minus symbols. The illustrative map centres around two key events—impending death (based on knowledge of death) and death itself—and is primarily focused on the patient's experience of the death trajectory, with the experiences of family and informal caregivers also being incorporated. The map goes beyond physiology to function and health capabilities, which include wellbeing and the capacity to achieve.58, 59 A map of a whole death system would include much more—for example, systems for preventing death and funereal customs.

Figure 3.

An example of a dynamic map of an end-of-life system

EoL=end of life. HCPs=health-care providers. PC=primary care. QoL=quality of life. R=reinforcing loop. B=balancing loop.

Section 4: Philosophical and religious underpinnings of death systems

Many philosophies and religions view life and death as part of a cycle where death is not seen as an ending but as a gateway to the next phase of life. The concept of Samsara—the continuous cycle of birth, life, death, and rebirth—is shared by several world religions, including Hinduism, Jainism, Sikhism, and Buddhism. The cycle of death and rebirth is dependent on karma, whereby actions in one life exert an influence on your future lives.

A belief in the continuity between the worlds of the living and the dead and of the continued existence of and interaction with those who have died underpins many belief systems. With indigenous African philosophies, the belief in the enduring presence of those who have died and of their continued interaction with the living is a defining feature, underpinning all spiritual life.60 Ancestors are not transformed into deities but rather remain as versions of the people they were when living.61 The interconnected nature of the living and the dead, with those who have died remaining present and active in the lives of the living, is a key feature of many African death systems.62

In New Zealand Māori traditions, a dying person must pass through the veil or ārai that separates the physical and metaphysical worlds.63 This transition is the focus of the care provided by the family or whānau at the end of life and allows the person to take up their place in the ancestral world.

Western philosophy, by contrast, has held death to be a final endpoint. In the Phaedo, Plato (429–347 BCE) describes the very activity of philosophising as a practice, or apprenticeship, for death.64 This same notion is taken up by Michel de Montaigne (1533–1592) in his essay That to Study Philosophy is to Learn to Die.65 The contemplative life of the philosopher is a way to approach death in a state of tranquillity. The philosopher seeks to show that death should not be feared. Epicurus (341–270 BCE) argues that “death, the most frightening of bad things, is nothing to us; since, when we exist, death is not yet present, and when death is present, then we do not exist.”66 Montaigne argues that to overcome the fear of death we must become death's neighbour and, in this way, “domesticate” death.65

The three Abrahamic faiths, Judaism, Islam, and Christianity, all share a belief in an afterlife and in resurrection. Judaism teaches that at the moment of death, the body and the soul separate and that while the body may disintegrate, the soul, the self, is eternal. Christianity preaches an afterlife in which after the Day of Judgement the good will reside eternally in heaven, while the sinful will be sent to hell. Belief in an afterlife is one of the six articles of faith in Islam, which believes in separation of the soul and the body after death. All three religions hold that life is a divine gift from God.

Confucianism does not talk about death directly but argues that seeking to prolong life can come at the expense of ren (benevolence, or supreme virtue); it may be necessary to accept death in order to have ren accomplished. Buddhism explicitly understands suffering as natural in four areas – in sickness, ageing, and death, but also in living itself. In Daoism, the context for discussing death is natural law, the way of following nature: death helps us to experience the whole process of life, to take a holistic view on life. Death is interior to life, a necessary part of life according to natural law.

This idea of the balanced natural law allows death to be valued as a homoeostatic mechanism necessary to life. Death is essential to life because without it there would be no life. Without death every birth would be a tragedy. It allows the old to give way to the young, evolution, and renewal. Similarly, death allows for new ideas and progress. As the German physicist Max Planck (1858–1947) observed, science advances not because scientists change their minds but because new generations come along.67 This principle is often paraphrased as “Science advances, one funeral at a time.”

This kind of argument is “consequentialist”: death has value because of consequences it enables or permits. Such arguments predominate, perhaps because it appears irrational to claim that death is valuable in and of itself, but some philosophers have argued just that.

Martin Heidegger (1889–1976) refocused philosophical attention on death from understanding the nature of death to our relation with death.68 He argued that our own death is not something that we can experience directly, whereas we can experience the imminence of our death. We can have a relation with our death which is yet to come. Death stands before us as the one event that it is impossible to avoid. Heidegger argues that it is an event for which no one can take responsibility on our behalf, no one else can die my death for me and through understanding this, facing up to this, and owning one's death, we may authentically become who we are. This points to a way in which death may give value to life.68

The French philosopher Emmanuel Levinas has said, “for us who witness the death of another person…there is in the death of the other his or her disappearance, and the extreme loneliness of that disappearance. I think that ‘the Human’ consists precisely in opening oneself to the death of the other, in being preoccupied with his or her death.”69 With this, Levinas shifts the focus again from our relation with our own death to our relation with the deaths of others. Panel 6 explores in more depth the concept of the value of death as a gift.

Panel 6. The gift of death.

In a recent interview the palliative care specialist and author Kathryn Mannix talked about the bereaved families who were not able to be present when their loved ones were dying of COVID-19: “These people don't know what the real story was and they realise that this not knowing is terrible, that being at a deathbed isn't a duty, but a gift.”70

The distinction between duty and gift takes us to the heart of thinking about the value of death. Duty is often understood as an obligation. In many cultures, caring for an ageing or dying parent is deemed to be a filial duty. In his essay De Brevitate Vitae [On the Shortness of Life], the classical Roman writer Seneca (died 65 CE) reflects on our sense that death comes too early in life, that we always “die before our season”.71 Death comes too soon because we fritter away so much of our lives on worthless activities. We wouldn't, he argues, give away our property, so why give away our lives? This transactional thinking reduces the value of death to what Karl Marx (1818–83) called “exchange value”.

Mannix's notion of the gift challenges this thinking and chimes with the work of the French anthropologist Marcel Mauss (1872–1950), who studied Native American culture and explored how the gift of being with dying people can build human relations based on reciprocity and exceed the regulated contract of exchange: there is a generosity in the gift that goes beyond any possibility of return.72

This thinking is developed by the French Jewish thinker Emmanuel Levinas (1906–95) who recognises that value derives from the uniqueness of a person's death and that one person's death is not simply equivalent to and therefore cannot be exchanged with another.69 There is no way by which the dying person can avoid their death. There is nothing, in that sense, that I can do. In being-for the other in their dying there is no return to be gained on my investment. There can only be loss. In this way, I am with the dying person in the same way that I am with a friend. There is a being-with, a communing, an attending-to, which is an end and a value in itself.

The value of this being-with in death does not derive from what follows as a consequence: the relation itself is the value. But what is the nature of this relation? Levinas talks of “a gratuitous movement of presence.”69 It is gratuitous because it is a giving that not only does not expect any return but that goes beyond the possibility of receiving anything in return. What can we give to the person who is dying? First and foremost, it is a gift of time—to give my time over to the person who is dying. To give time to the other in death is the condition of possibility of the being-with which is itself the condition of possibility of communing with the dying person, and thus in turn of community more generally. In the generosity of the gift of time to the person who is dying, a new sense of value is created, and with it a new possibility for giving value to death and to dying.

This might sound fanciful, but the palliative care physician and writer Kathryn Mannix has said that “being at a deathbed isn't a duty, but a gift”.70 Irish writer Kevin Toolis described attending his father's wake as a gift because it taught him how to die.73 There are also many accounts in both academic studies and general writing of people finding dying to be a positive rather than negative experience.74 Gandhi (1869–1948) talked of the joy he found in nursing his brother-in-law as he died: “all other pleasures and possessions pale into nothingness before service which is rendered in a spirit of joy.”75

For many communities, illness, death, and grief are times at which connections are at their strongest. The Zulu phrase umuntu ngumuntu ngabantu (“A person is a person through other persons”) is a core idea underpinning and defining Ubuntu philosophy, which is sometimes referred to as the African conception of humanism.76 Personhood exists within a community and is premised on connectedness, famously described by the cleric and theologian Desmond Tutu (1931–2021) in his quote: “My humanity is caught up, is inextricably bound up, in yours. We belong in a bundle of life.”77 Kenyan philosopher John Mbiti (1931–2019) has explained Ubuntu (meaning “humanity”) as “I am because we are, and since we are, therefore I am,”78 which contrasts with the saying by French philosopher René Descartes (1596–1650) “I think, therefore I am.” An important application is that “whatever happens to the individual happens to the whole community, and whatever happens to the community happens to the individual as well.”79 When an individual dies, their death is inextricably linked to and experienced by the community.

Religious, philosophical, and spiritual perspectives on death and dying are fundamental to understanding different death systems, informing many of the implicit assumptions, values, and behaviours that define them.

Section 5: Historical origins of death systems

Archaeological exploration of graves and burial sites can provide insights into historical practices around death, dying, and bereavement and the death systems they were part of. Many sites are now major tourist attractions, such as the pyramids in Egypt or the Terracotta Army in China, and they offer important insights into human responses to mortality and loss. Archaeological materials relating to historical care of the dead have been used to facilitate discussions about contemporary death and dying and understand and reflect on biases, expectations, and norms.80

The historian Philippe Ariès (1914–1984) examined death from a Western perspective and identified four phases.81 Before the 12th century he describes a period of “Tamed death,” where death was familiar, and people knew how to die. The dying and their families accepted death calmly; they knew when death was coming and what to do; dying was a public event attended by children. Later came “One's own death,” where death became more personalised. The imminence of judgement, introduced by Christianity, meant the dying had heaven to hope for or hell to fear; they had a stake in their death. The 18th century saw a shift towards “Thy death,” where death began to be dramatised, revered, and feared and was seen as discrete from the normal flow of life. Ariès describes the final phase as “Forbidden death,” which coincides with the arrival of scientific progress and the modern hospital: death is “unwanted and fought against…on the hospital bed, while one is unconscious, alone, and…[trying] to eschew death until the last minutes.”81

The social critic Ivan Illich (1926–2002) argued that death has become steadily medicalised since the Middle Ages.83 In the 15th and 16th centuries, doctors in Palermo, Fez, and Paris argued intensely about whether medicine could prolong life, with many insisting that attempts to interfere with the natural order were blasphemous. The English philosopher Francis Bacon (1561–1626) was the first to describe prolonging life as one of the functions of medicine, but it was another 150 years before this role became a possibility. At first only the rich could expect that doctors would delay death. However, argued Illich, by the 20th century this expectation had come to be seen as a civic right. “Thanks to the medicalisation of death, healthcare has become a monolithic world religion,” writes Illich; “‘Natural death’ is now the point at which the human organism refuses any further input of treatment.”82 He also argued that what he called “mechanical death” had been exported: “The white man's image of death has spread with medical civilisation and has been a major force in colonialisation.” The growing movement to decolonise global health “by grounding it in a health justice framework that acknowledges how colonialism, racism, sexism, capitalism and other harmful ‘-isms’ pose the largest threat to health equity”83 is a response to this historical background, as is the movement to decolonise death studies, death practices,84 and end-of-life care.7

Section 6: Power, discrimination, and inequity in death systems

Death systems are not benign. They can replicate and reinforce discrimination and inequity. Power resides within systems, and the systems often maintain the interests of those holding power.

Individual or community experiences of death, dying, and bereavement are determined by a constellation of factors such as political unrest or conflict, access to and trust in health-care services, relationships, discrimination or oppression, poverty, education, and many others. These determinants interact with each other to create unique sets of experiences for people at the end of life. These non-medical aspects of why, how, and where people die or grieve are understood collectively as the social and structural determinants of death, dying, and bereavement. They share a great deal with the social determinants of health.85

2020 will be remembered as a year in which these determinants of death, dying, and bereavement loomed large. Firstly, the coronavirus pandemic brought death into the daily lives of all people around the world. Understood initially as an indiscriminate virus, infecting rich and poor people equally, data soon emerged showing that mortality and morbidity were concentrated among disadvantaged people, with increased death rates for many minority ethnic communities in high-income countries.86 A second major event of 2020, the murder of a Black man, George Floyd, by a police officer in the USA, sparked a global protest. These events forced wider recognition of the influences of discrimination, inequity, power, and oppression on how and why people die.87

The impact of race, gender, sexuality, socioeconomic status, or other forms of discrimination on mortality rates, access to care, or the incidence of diseases or conditions is well established. Black mothers in the USA are three times more likely to die from preventable pregnancy-related complications than are White mothers88 and this racial difference has persisted despite nationwide efforts to improve maternal mortality. Black Americans are at twice the risk of losing a mother and about 50% greater risk of losing a father by age 20 years compared with White Americans.89 Growing evidence on adverse childhood experiences provides an explanation of how cycles of disadvantage and trauma can persist within families and communities, with important effects on mortality rates.90

People identifying as LGBQT+ have increased rates of preventable deaths and face barriers accessing health services.91 Rates of cardiovascular disease, disability, and poor mental health are higher in adults older than 50 years who identify as lesbian, gay, or bisexual, compared with heterosexual populations.91 Improving access to end-of-life care has been highlighted as a specific challenge.92

Women are traditionally viewed as the caregivers at times of ill-health and dying: women spend on average 2·5 times as much time on unpaid care and domestic work as men.93 The Lancet Commission on Women and Health found that women contribute almost 5% of global gross domestic product through health caring and that about half of this is unpaid work.94 Unpaid caring, much of which consists of caring for ill or dying people, tends to be undervalued and unprotected and is undertaken with little or no training or support.95

The data show inequity across the life course because of race, ethnicity, class, gender, or sexual orientation but people do not experience these factors in isolation. Intersectionality is the understanding of how these factors interact and intersect to create different and multiple experiences of discrimination and disadvantage.96 Being female is linked with disadvantage, but being a migrant woman of colour, an unpaid carer, or a lesbian woman with a disability is likely to bring further disadvantage. In panel 7 , Mpho Tutu van Furth, a Black South African woman, and Commissioner, reflects on race, gender, and the value of death.

Panel 7. Race and the value of death.

“Race is not real, yet it can control us. We now understand that race is an idea constructed by a power elite to justify the dehumanisation of people in order to subjugate, exploit, enslave, and kill them without repercussion.”

Hanuman Goleman97

Mpho Tutu van Furth, member of the Commission, writes:

This Commission has centred the story of the value of death in a relatively wealthy, mostly White, and predominantly western perspective. What this means is that White, western, and relatively wealthy is the norm to which every other experience must refer. Most people in the world do not have to wrestle with an over-medicalised death, they have minimal access to quality health care.

I cannot address the perceptions and experiences of two thirds of the world population. I will speak to my own experience. I am a Black South African woman and the mother to two African American children. In the two contexts in which I lived longest, South Africa and the USA, Black people have never had to engage in a fight to die. Society and the medical world have considered Black lives cheap. I was a teenager when the Soweto uprisings erupted in 1976. I saw then the naked brutality of the apartheid police. I understood then how cheap Black lives were to the White regime. The police first used tear and rubber bullets on the protesters. Then they used batons, rawhide whips, and live ammunition on the children.

Growing up I saw the White flight from ageing and death. I wondered why my mother didn't hide her grey hairs or guard her girlish figure like the mothers of my White friends. “I earned my grey” she would say. She, coming from a culture in which our elders were honoured, even revered. “I have daughters” she would say turning gracefully, and gratefully, into her old age. The cause of death is birth. Black people had no illusion that we could avoid death. Black South Africans did not desire immortality. In death we would be gathered to our ancestors. “Going home” to our forebears was considered the reward for life well lived.

The experience of the vast majority of Black people in the post-apartheid South Africa closely resembles that of African Americans. Although they are putatively citizens of a free non-racist society, health, wealth, and opportunity in South Africa remains largely in the hands of the white population. As in the USA, the referential norm is White. In both societies the Black person is “othered”. The consequences of this othering and the opportunity hoarding which is its partner are evident in the COVID-19 pandemic.

The COVID-19 pandemic was initially described as an equal opportunity assailant striking rich and poor, Black and White alike. It soon became evident that this was untrue. The rich could escape to their second homes. The middle class could, for the most part, work from home. It is the poor who are bearing the brunt of this pandemic. In South Africa one legacy of apartheid is the vast overpopulated Black townships that surround every city. People live cheek by jowl. In many homes there is no running water. Social distancing is an unachievable dream. If they have work, the denizens of the townships are not people who can work from home. This population of cooks, cleaners, and grocery store clerks probably carried the killer virus from the affluent White suburbs to the impoverished townships. For African Americans the story is much the same. In addition to being essential workers, African Americans bear the imprint of the constant stress of institutionalised racism in their bodies. This “weathering” can be the underlying condition that leads to elevated rates of COVID-19 related deaths among African Americans.