ABSTRACT

Tomatoes are the second most consumed vegetable in the United States. In 2017, American people consumed 9.2 kg of tomatoes from a fresh market and 33.2 kg of processed tomato products per capita. One commonly asked question by consumers and the nutrition community is “Are processed tomato products as nutritious as fresh tomatoes?” This review addresses this question by summarizing the current understandings on the effects of industrial processing on the nutrients and bioactive compounds of tomatoes. Twelve original research papers were found to study the effects of different industrial processing methods on the nutrients and/or bioactive compounds in tomato products. The data suggested that different processing methods had different effects on different compounds in tomatoes. However, currently available data are still limited, and the existing data are often inconsistent. The USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference Legacy was utilized to estimate nutrient contents from raw tomatoes and processed tomato products. In addition, several other important factors specifically related to the industrial processing of tomatoes were also discussed. To conclude, there is no simple “yes” or “no” answer to the question “Are processed tomato products as nutritious as fresh tomatoes?” Many factors must be considered when comparing the nutritious value between fresh tomatoes and processed tomato products. At this point, we do not have sufficient data to fully understand all of the factors and their impacts.

Keywords: tomatoes, industrial processing, tomato product, nutrient, bioactive compounds

Statement of Significance: There is no simple answer to the question “Are processed tomato products as nutritious as fresh tomatoes?” based on current available data. Many factors must be considered, and more research is needed to fully address this question.

Introduction

Fruits and vegetables are major contributors of a number of nutrients that are currently reported to be underconsumed in the United States—specifically certain vitamins and minerals (1). In addition to maintaining normal physiological functions, a diet rich in fruits and vegetables has been associated with a reduced risk of many chronic diseases (2–4). Fruits and vegetables are commonly sold and consumed as raw/uncooked, as well as in various processed forms for enhanced availability, convenience, and affordability. Processed fruits and vegetables, such as frozen and canned forms, were found to contribute significantly to total fruit and vegetable daily nutrient intake (5). Certain vulnerable populations, such as the elderly and those who live in so-called “food deserts” having limited availability of fresh fruits and vegetables, or perhaps due to preference, consume considerably more processed fruits and vegetables (6, 7). Nevertheless, negative perceptions about “processed foods” exist due to the mischaracterization of processed foods as unnatural, unsafe, and/or less nutritious by some health professionals, advocacy organizations, and the media (5, 8). For instance, more than half (57%) of Americans disagree that canned food is as nutritious as unprocessed food and more than one-third (37%) disagree that canned food is as nutritious as frozen varieties (9).

Common food-processing methods, such as freezing, canning, and drying, have been known to influence the nutrients and bioactive compounds in fruits and vegetables (10, 11). Although processed foods are generally thought to be inferior to unprocessed foods, “processing” is not necessarily a negative word, and processed foods are not always nutritionally poor or unhealthy (12). Food processing may offer beneficial effects such as improved digestibility and bioavailability of nutrients, and certainly increases food safety (13). Processed foods are nutritionally important to American diets, and they contribute to both food security and nutrition security (14). To accurately assess nutrient intake from total fruit and vegetable consumption and their health outcomes, it is critical to understand the processing/packaging effects on the nutrients and bioactive compounds of processed fruits and vegetables.

Tomatoes are the second most consumed vegetable in the United States, only behind potatoes (15). Approximately 1.42 million tons of fresh market tomatoes and 14.7 million tons of processed tomatoes were harvested from approximately 311,500 acres in 2017, with a total value of approximately $1.67 billion (16). Because tomatoes withstand heating and cooking processes very well, a wide range of popular and convenient tomato products are available domestically. In 2017, American people consumed 9.2 kg of tomatoes from a fresh market and 33.2 kg of processed tomato products per capita (16). Canned tomatoes are the most popular canned vegetable in the United States. Among condiments, salsa and ketchup are number 1 and number 2, respectively.

Because more processed tomato products than raw tomatoes are consumed in the United States, one commonly asked question by consumers and the nutrition community is “Are processed tomato products as nutritious as fresh tomatoes?” The answer to this question will help consumers make better food choices, and help nutritionists, dietitians, and policy makers make appropriate dietary recommendations. However, “nutritious” is a rather vague and scientifically less defined word. This question can be addressed by answering 2 scientifically measurable questions: 1) from the viewpoint of food chemistry, “What are the changes in nutrients and bioactive compounds in tomatoes after industrial processing?” and 2) from the viewpoint of nutrition, “When consumed in the same amounts, do fresh tomatoes and processed tomato products provide the same types and amounts of nutrients and bioactive compounds?” The aim of this review was to look for answers to these 2 questions by summarizing the current available data. The knowledge gap and research needs were also identified and discussed for future research directions.

Major Nutrients and Bioactive Compounds in Tomatoes

Tomatoes have modest to high concentrations of several important nutrients, including vitamin C, vitamin A (as provitamin A), folate, and potassium (17). The dry matter of tomatoes is generally between 5% and 10%. In mature tomatoes, three-quarters of the dry matter is made up of solids, mainly sugars (∼50%), organic acids (>10%), minerals (8%), and pectin (∼7%) (18). Glucose and fructose are the primary sugars present, although other sugars have also been reported at low levels, including raffinose, arabinose, xylose, galactose, and sugar alcohol, myoinositol (19).

Carotenoids are the major class of bioactive compounds present in tomatoes. Two groups of carotenoids were found in tomatoes: 1) carotenes, which are nonoxygenated molecules including lycopene, β-carotene, α-carotene, γ-carotene, δ-carotene, ξ-carotene, phytoene, phytofluene, and neurosporene, and 2) oxygen-containing xanthophylls such as β-cryptoxanthin, lutein, zeathanxin, neoxanthin, and canthaxanthin. The most abundant carotenoid in tomato is lycopene (60–90% of total carotenoid on a per weight basis), followed by phytoene (5.6–12%), γ-carotene (1–11%), neurosporene (0–9%), phytofluene (2–5%), β-carotene (1–5%), and lutein (0.1–1%), with trace amounts (<1%) of other carotenoids (20–24). Among the carotenoids in tomatoes, β-carotene, α-carotene, and β-cryptoxanthin are the forms of provitamin A that can be converted into vitamin A in the human body. The types and concentrations of carotenoids in tomatoes vary considerably based on the cultivars, stage of maturity, environmental factors, and growing conditions (25). Lycopene and other carotenoids occur primarily in the all-trans configuration (also called all-E-isomers) in tomatoes (24, 26). The cis-forms (Z-isomers) of carotenoids, such as 5-cis, 9-cis, 13-cis, and 15-cis lycopene (27), also exist naturally in tomatoes. Their percentages are determined by the varieties and strongly affected by the stage of ripeness. It was shown in 1 study that, from green to red, percentage of cis-forms of lycopene ranged from 0–8.83% for 1 variety to 0–14.22% for another variety (28).

Tomatoes contain a range of flavonoids and phenolic acids. Rutin (quercetin-3-O-rutinoside), naringenin chalcone, and quercetin are major flavonoids in raw tomatoes. Naringenin, myricetin, kaempferol, and their glycosides are also found in tomatoes but in low concentrations. The hydroxycinnamic acids, such as chlorogenic and caffeic acids, and chlorogenic acid derivatives, such as 5-caffeoylquinic acid, 4-caffeoylquinic acid, and 3,4-dicaffeoylquinic acid, are the major phenolic acids in tomatoes. Minor phenolic acids, including p-coumaric and ferulic acids, as well as their glucosides, were also detected in tomatoes (22, 29, 30). Similar to carotenoids, the types and concentrations of phenolic compounds in tomatoes also varied significantly based on the cultivars, stage of maturity, environmental factors, and growing conditions (28, 30).

Industrial Processing of Tomatoes

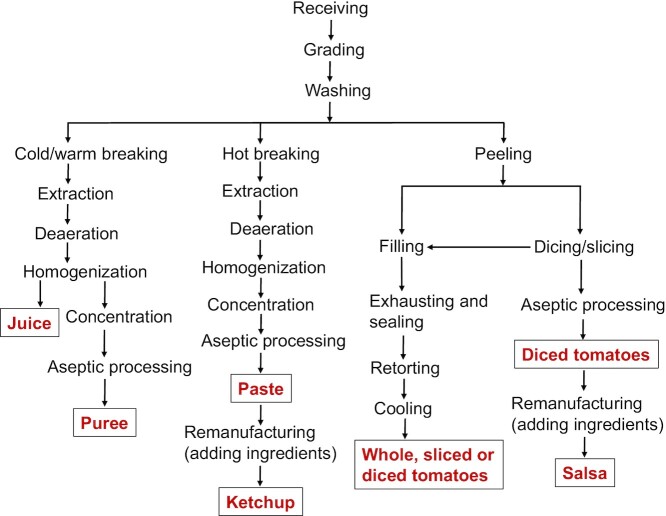

Industrial tomato processing includes multiple steps and varies depending on the final product to be obtained. In the United States, the most commonly consumed tomato products are canned tomatoes and sauce, juices, and condiments/salad dressings (15). The general industrial tomato processing procedures are illustrated in Figure 1. The key steps are described as follows based on the literature (31):

FIGURE 1.

General industrial processing procedures for different tomato products.

Receiving and grading: The tomatoes used in industrial processing are called “processing tomatoes,” which are mostly different varieties of plum tomatoes. After harvesting, tomatoes are transported to the processing plant within hours. Then, the tomatoes go through grading to determine the quality.

Washing: Washing is a critical control step in producing tomato products with a low microbial count. Chlorine is frequently added to the water to keep down the number of spores present in the flume water.

Peeling: Tomatoes are typically peeled before further processing for certain products (canned whole, sliced, and diced tomatoes). There are 2 commonly used peeling methods: steam and lye. Currently, steam is the most widely used approach to facilitate peeling. Other less commonly used peeling methods include freeze-heat peeling and hot calcium chloride.

Breaking: The tomatoes are chopped and crushed at this step. Tomatoes can be processed by either a hot break or cold break method. Most hot break processes occur at 93–99°C. In the cold break process, tomatoes are chopped and then mildly heated to accelerate enzymatic activity and increase yield. Cold break juice has less destruction of color and flavor but also has a lower viscosity because of the activity of the enzymes. Its lower viscosity is a special advantage in tomato juice and juice-based drinks.

Extraction: After breaking, the comminuted tomatoes are put through an extractor, pulper, or finisher to remove the seeds and skins. Juice is extracted with either a screw-type or paddle-type extractor.

Deaeration: This step is to remove dissolved air incorporated during breaking or extraction. It is carried out by pulling a vacuum on the juice. Deaeration decreases oxidation and prevents foaming during concentration.

Homogenization: The juice is homogenized to increase product viscosity and minimize serum separation.

Concentration: If the final product is not juice, the juice is concentrated to paste or purée.

Can filling: Although tomatoes usually are considered as a high-acid food (pH <4.6), some varieties of processing tomatoes have pH values above 4.6. In this case, the product can be acidified to reduce the pH to 4.6 or lower by adding lemon juice or citric acid.

Aseptic packaging: The product is pasteurized, then cooled and filled into sterile containers.

Retorting: Most canned tomato products undergo the sterilization process to destroy pathogenic organisms and to ensure an adequate shelf life. Exact processing conditions depend on the product being packed, the size of the can, and the type and brand of retort used. The key is for the internal temperature of the tomatoes to reach at least 88°C.

Processing of tomatoes into different end products includes mechanical treatments, several thermal treatment steps, and the addition of ingredients such as calcium, oil, or salt, which may result in changes in nutrient profiles and bioavailability (32).

Literature Search and Data Extraction

A scoping review was conducted based on the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) approach (33) to answer the first research question. A systematic literature search was performed for the period 1980–2020. PubMed and Google Scholar were selected as primary search engines. The following keywords were used in different combinations: tomato, processing, industrial processing, bioavailability, nutrient, carotenoid, vitamin, mineral, lycopene, phenolic, flavonoid, sugar, paste, juice, puree, sauce, ketchup, and pomace. Records yielded from the database searches were assessed for their potential relevance according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Data were extracted from the full-text papers and subsequently reviewed. Reference lists of the retrieved research and review articles were reviewed to identify references not found using electronic search engines. The detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria are described as follows:

Only data in original research articles were included; secondary data in review articles or books were excluded.

As this paper focused on industrial processing, data on other processing methods such as domestic cooking and preparation by the food service industry were excluded.

It has been shown that the physical and chemical characteristics and nutritional profile of processed products from laboratory-scale processing yielded significant deviations from industrial-scale processing (34, 35). To reflect what are realistically consumed, only the data of industrial processing conducted in manufacturing facilities or pilot plants were included, whereas the experiments conducted in the laboratories were excluded.

The information obtained from the scoping review as well as the data in USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference Legacy Release (SR-Legacy) (36) were utilized to address the second research question.

Overview of the Publications and the Data

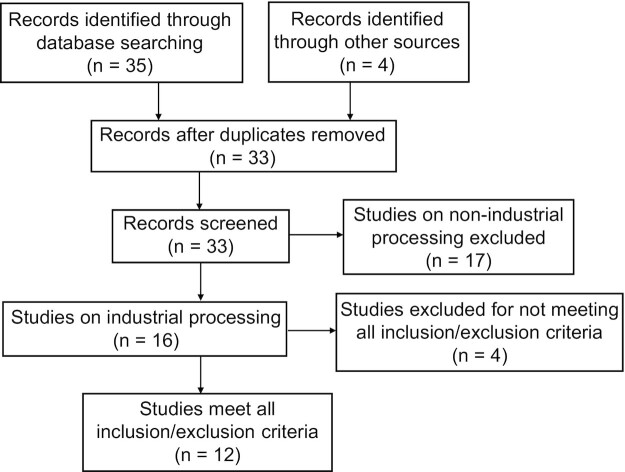

After several sequential stages of screening, 12 original research papers were found to meet all inclusion and exclusion criteria (Figure 2). These studies investigated the effects of industrial processing on the nutrients and/or bioactive compounds in common tomato products (37–48). The results of these studies are summarized in Table 1. Interestingly, these 12 studies were conducted in 8 different countries. They used different processing methods and/or conditions and different varieties of tomatoes, which may introduce significant variations. Two studies were published in the early 1980s. As both varieties/cultivars of processing tomatoes and processing methods have evolved considerably since then, these early data may be outdated.

FIGURE 2.

PRISMA flow diagram of literature search and screening. PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

TABLE 1.

Effects of industrial processing on the nutrients in tomato products (based on dry weight)1

| Country | Starting materials | Processing facility | Products | Dietary components | Results of the changes in processed products | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hungary | Ripe fruits of 12 tomatoes for fresh consumption (salad tomatoes) and 15 processing cultivars | Processing plant | Paste | Tocopherol, carotenoids, ascorbic acid | Ascorbic acid ↓α-Tocopherol ↓α-Tocopherol quinone ↓γ-Tocopherol ↓Other carotenoids →All-trans-lycopene ↑Total carotenoids ↑trans β-Carotene ↓cis β-Carotene ↑ | (37) |

| Germany | Fresh Spanish tomatoes | Pilot plant | Sauce | Tocopherol | α-Tocopherol ↑(E)-lycopene → | (38) |

| France | Red tomatoes and yellow tomatoes | Pilot plant | Purée | Carotenoids, vitamin C, phenolics | Red tomatoes Lycopene → β-Carotene → Vitamin C ↓ Total phenolics ↓Yellow tomatoes β-Carotene ↓ Vitamin C ↓ Total phenolics ↓ | (39) |

| USA | Fresh tomatoes | Processing plant | Canned tomatoes | Minerals | Calcium, chloride, cobalt, copper, nickel, sodium, tin, and zinc ↑Magnesium, manganese, phosphorus, potassium, and silicon ↓Iron →Element retention in the canned tomatoes was 77–7681% | (40) |

| Egypt | Roma variety tomato | NA | Juice and concentrate | B vitamins, vitamin C, vitamin A, and minerals | Vitamin C ↓Riboflavin ↓Vitamin A ↓Niacin ↑Thiamin →Ca, Cu, Fe, Mg, Mn, Ni, K, Na, and Zn ↑Pb was found only in the final products | (41) |

| USA | Processing tomatoes (variety BOS 3155) | Two processing plants | Paste | Carotenoids | Lycopene ↓The losses were different for samples picked in different years, and processed at different plants | (42) |

| France | Nautico, Montégo, and Elégy varieties | Processing plant | Paste | Carotenoids, phenolics, vitamin C | (E)-Lycopene →(Z)-Lycopene ↓(E)-β-Carotene ↓Ascorbic acid ↓Rutin →Kaempferol-3-rutinoside →Naringenin chalcone ↓Naringenin-7-O-glucoside →Naringenin ↑Caffeic acid-4-O-glucoside ↑p-Coumaric acid-4-O-glucoside ↑5-O-Caffeoylquinic acid ↑3,5-Dicaffeoylquinic acid ↑3,4-Dicaffeoylquinic acid ↑4,5-Dicaffeoylquinic acid ↓Tricaffeoylquinic acid ↓ | (43) |

| USA | Mixed cultivars AB2, Peto 849, Heinz 9995, and Heinz 9780 | Processing plant | Paste | Carotenoids, vitamin C, phenolics | Ascorbic acid ↓Total vitamin C2 ↓β-Carotene ↓Lycopene →Quercetin →Kaempferol ↑ | (44) |

| Turkey | Shasta variety (processing tomatoes) | Processing plant | Paste | Carotenoids, vitamin C, phenolics, tocopherols | All-trans lycopene ↓β-Carotene ↓Lutein ↓Vitamin C ↓α- and β-tocopherol →δ- and γ-tocopherol ↓Rutin →Rutin apioside →Naringenin ↑Naringenin chalcone ↓Chlorogenic acid → | (45) |

| Spain | Variety “Pera” | Pilot plant | Two types of paste with different ºBx | Carotenoids, phenolics | Lycopene in the 10ºBx tomato paste ↑Lycopene in the 15ºBx tomato paste ↓β-Carotene ↓Total phenolic compounds ↑Total flavonoids ↑Quercetin ↑Rutin ↑ | (46) |

| Kaempferol ↓Chlorogenic acid ↑Caffeic acids ↑Ferulic acid ↓p-Coumaric acid ↓ | ||||||

| UK | Italian tomato variety (Sorrento) | NA | Sauce, paste | Phenolics, lycopene | All-trans lycopene ↑Isomerization of lycopene occurred Chlorogenic acid ↑Rutin ↓Naringenin ↓ | (47) |

| Turkey | A commercial variety | Processing plant | Sauce | Phenolics | Chlorogenic acid →Rutin ↑Naringenin chalcone ↓Naringenin ↑ | (48) |

NA, not available; upwards arrow indicates increase, downwards arrow indicates decrease, rightwards arrow indicates no changes; ºBx, degree Brix.

Total vitamin C: ascorbic acid plus dehydroascorbic acid.

Effects of industrial processing on major nutrients and bioactive compounds in tomatoes, including carotenoids, vitamins, minerals, and phenolic compounds, were examined. However, the number of publications devoted to different classes of compounds are unequal. Carotenoids, mainly lycopene and β-carotene, were studied in 9 papers. The effects of industrial processing on phenolic compounds in tomatoes were assessed in 7 studies. Vitamin C appeared in 6 studies. Only 3 studies included the measurement of vitamin E. The effects of industrial processing on B vitamins and minerals/metals were evaluated in 2 early studies published in the 1980s.

Question 1: What Are the Changes in the Nutrients and Bioactive Compounds of Tomatoes after Industrial Processing?

Current knowledge

Fresh tomatoes and processed tomato products contain different levels of moisture and total and soluble solids. For example, most fresh processing tomatoes contain about 5–6% soluble solids (49), whereas tomato paste can be produced to have anywhere from 20% to 37% soluble solids depending upon manufacturing needs (44). To understand the true changes, the comparisons must be made between the data expressed on a dry weight basis to account for changes in moisture (50).

The currently available data on the effects of industrial processing on carotenoids are inconsistent and sometimes conflicting. For example, after tomatoes were processed into paste, lycopene was found to increase in 2 studies, decrease in 2 studies, and remain unchanged in 4 studies. One study showed that, depending on the degree Brix (ºBx; the degree Brix is defined as the sugar content of an aqueous solution, and it is also the most common scale for measuring soluble solids in the food industry) of tomato product (paste), the concentration of lycopene could increase or decrease (45). For β-carotene, however, 5 of 6 studies showed that it decreased after industrial processing, and only 1 suggested no change (Table 1). The discrepancy of the data can be explained as follows:

Types of carotenoids. The thermal stability of carotenoids is determined by their chemical structures and the locations in the cell compartment of unprocessed tomatoes. For example, in raw tomatoes, the linear all-trans form of lycopene aggregates into crystalline structures located within chromoplasts, which grants lycopene greater thermal stability (51), whereas β-carotene appeared to be less stable to heat treatment (52).

Processing method and condition. Processing method and condition (time, temperature, peeling method, etc.) hugely impact carotenoids in tomato products. Higher processing temperatures and longer processing times are generally associated with increased losses. One study found that the changes in lycopene depended on the processing conditions—the level increased in the 10 ºBx tomato paste, while further processing into 15 ºBx tomato paste reduced the lycopene content (46).

Types of tomatoes. Different cultivars of processing tomatoes differ from each other with regard to the nutrient contents, soluble solids, and titratable acidity, all of which may further influence the outcome of the available/releasable nutrients and dietary compounds after processing. It was shown that higher levels of soluble solids and titratable acidity are desirable for the production of tomato paste, as tomatoes with these attributes require less thermal treatment, and thus result in less loss of nutrients (18, 49). Another interesting finding is that industrial processing did not affect β-carotene content in red tomatoes, but significantly lowered it in yellow tomatoes (39).

Growing conditions. Growing conditions and other environmental factors may influence the chemo-physical properties of tomatoes, which, in turn, impact the contents of carotenoids in finished tomato products. As an example, Takeoka et al. (42) found that the ºBx of fresh processing tomatoes varied between the 2 consecutive years harvested from the same areas. In particular, for same variety of tomatoes that were processed in the same plant, the ºBx was 5.4 in 1998 and 4.9 in 1999. Paste processing resulted in no significant loss of lycopene in 1998 but a 28% loss in 1999. The greater loss that occurred in 1999 was suggested to be related to the slightly lower Brix level for the fresh tomatoes, thus requiring a longer processing time to achieve the final Brix value of the paste.

Isomerization of carotenoids occurs during thermal processing. Carotenoids primarily exist as all-trans forms in unprocessed tomatoes, which can be potentially converted into cis-forms during heat treatment. Industrial processes alter the isomeric forms and amounts of carotenoids in tomato products based on their chemical structures, the amount and type of heating, length of processing, and oxygen presence (53). Lycopene was shown to be more resistant to isomerization than β-carotene when processed under the same method and conditions (37). On the contrary, 1 study found that, when tomatoes were processed into paste, lycopene cis-isomers decreased by ∼2-fold in the paste, while all-trans lycopene remained unchanged (43). This indicated that partial retro-isomerization of cis-isomers of lycopene into the most thermodynamically stable trans lycopene could have occurred. The loss of β-carotene during industrial processing could be partly explained by the formation of cis-isomers such as (13Z)-β-carotene (43). The fact that β-carotene readily isomerizes during the processing, whereas lycopene remains relatively stable, suggests that these carotenes have different bond energies and kinetics for isomerization reactions (54).

Thermal processing was found to significantly reduce vitamin C contents in tomato products in all 6 related studies. Vitamin C is known to be one of most labile vitamins in our food supply and can be significantly lost during thermal processing (55).

Three studies included the measurement of vitamin E, one of which found that the contents of α-tocopherol, α-tocopherol quinone, and γ-tocopherol all decreased when tomatoes were processed into paste (37), while in another study, δ- and γ-tocopherol decreased and α- and β-tocopherol remained unchanged after paste processing (45). α-Tocopherol was shown to significantly increase when tomatoes were processed into sauce in the third study (38).

In an early study published in 1982, vitamin A (as forms of provitamin A) and riboflavin decreased, niacin increased, and thiamin did not change in tomato juice and concentrate compared with fresh tomatoes (41).

The effects of industrial processing on minerals/metals in tomatoes were investigated in 2 studies. In the first study (41), 10 elements (calcium, copper, iron, magnesium, manganese, nickel, potassium, sodium, zinc, and lead) were determined in the fresh tomato and canned tomato juice and concentrate. All metals showed slightly higher concentrations in juice and significantly higher concentrations in tomato concentrate. Lead was absent in fresh tomato, but was found in tomato juice and concentrate, indicating possible contamination during processing. In the second study, the contents of 16 essential elements were measured in fresh and canned tomatoes (40). Fresh-canned tomatoes' retention of 14 elements was calculated to be 77–7681%. Eight elements showed greater than 100% retention, including calcium (460%), chloride (782%), cobalt (200%), copper (114%), nickel (200%), sodium (7,681%), tin (≥423%), and zinc (135%). The significant increases in calcium, chloride, cobalt, nickel, tin, and especially sodium were largely due to the addition of salt tablets in the processing. The increases in other elements were attributable to contact with metal parts or containers along the processing line. Less than 100% retention was observed for magnesium (81%), manganese (77%), phosphorus (80%), potassium (87%), and silicon (89%). No significant difference in iron (107%) was found between fresh and canned samples.

Flavonoids and other phenolic compounds are important bioactive compounds in fruits and vegetables. Their availabilities have been shown to be influenced by several food processing methods (56, 57). Like carotenoids, the effects of industrial processing on total and individual phenolic compounds are inconsistent. Heat treatment was shown to significantly increase total phenolics and total flavonoids when tomatoes were processed into paste (46), and longer thermal treatment time that resulted in higher total and soluble solids led to even higher total phenolics and total flavonoids (46). This phenomenon was explained by increased extractability due to rupture of the cell structure during thermal processing. However, in another study, the total polyphenol content decreased significantly during purée processing both in red (43%) and yellow (28%) tomatoes (39). It is noteworthy that, in the aforementioned studies, the total phenolics were measured by the Folin-Ciocalteu assay and the total flavonoids were measured based on the aluminum chloride method. Both of these methods are nonspecific colorimetric methods (58, 59), and the results can be influenced by several factors such as sample matrix and/or interfering components (e.g., other reducing agents for the Folin-Ciocalteu assay and other nonflavonoid polyphenols for the aluminum chloride method) (60, 61).

The changes in individual phenolic compounds during industrial processing were different in the different studies (Table 1). Rutin, the most abundant flavonoid in tomatoes, was found to increase (46) or remain unchanged (43, 45) after tomatoes were processed into pastes. In the process of sauce making, rutin was found to increase in 1 study (48) but decrease in another study (47). Processing method and condition are the major factors determining the changes in phenolic compounds. Other factors, such as the chemical structure and variety of tomatoes, also play important roles. The outcome is likely the net effects of increased extractability and loss due to thermal and mechanical processing. One common finding is that, after thermal processing, when tomatoes were processed into paste or sauce, naringenin chalcone consistently decreased while naringenin consistently increased (43, 45, 48). In raw tomatoes, naringenin chalcone is one of the major flavonoids, and naringenin is a minor one that is not even detectable in some varieties. However, naringenin concentration was 20-fold higher in industrial processed sauces compared with fresh tomatoes. This is likely the consequence of the high temperature at low pH, under which conditions conversion of naringenin chalcone to naringenin is stimulated (45, 48).

Limitation and research needs

Currently available data on the effects of industrial processing/packaging on nutrient and bioactive compounds in tomatoes are still limited, and the existing data are often inconsistent and sometimes conflicting. Only a handful of compounds were evaluated by more than 3 studies. Information on the effects of industrial processing on certain nutrients is either not available or outdated. For instance, effects of industrial processing on carotenoids other than lycopene and β-carotene are seldomly studied. Vitamin A and some B vitamins were only investigated in 1 study published in 1982 (41), and minerals in tomatoes before and after industrial processing were measured in 2 studies published in 1981 (40) and 1982 (41). These early data may not even be relevant currently. Except for vitamin C, there is a lack of consensus on how industrial processing alters other nutrients and bioactive compounds based on currently available data. Not only do we have insufficient data, but the available data are also sparse. The 12 studies included in this section were conducted in 8 different countries, which may be the major reason for the mixed results because different processing methods, varieties of tomatoes, and analytical approaches were used in these studies.

Tomato processing is ever changing along with the development of new technology and the new varieties of processing tomatoes. Advanced processing technologies such as high-pressure processing, which utilizes less energy and results in a higher quality product, are being studied and, to some extent, commercialized. In contrast to the conventional hot-break method currently utilized in the tomato industry, a novel processing technology, called high temperature with shear (HTS) processing, was shown to perform better at retaining lycopene and vitamin C contents (62). In addition, the processing tomato cultivars are also constantly changing to make them more suitable for processing. For instance, tomatoes were once cored to remove the stem scar (coring). Modern tomato varieties have been bred with very small cores so that this step is no longer needed (31). Another recent development is that breeding of multi-use and extended field storage (EFS) cultivars has dominated in California and other locations in recent years (63). Therefore, more studies are needed to keep up with these advancements.

Question 2: When Consumed in the Same Amounts, Do Fresh Tomatoes and Processed Tomato Products Provide the Same Types and Amounts of Nutrients?

The data summarized in Table 1 show us what happens chemically to the nutrients and bioactive compounds in tomatoes after industrial processing, and by doing so the data were calculated and compared based on the dry weight. When we attempt to answer the second question, it is important to point out that, from consumer and nutrition perspectives, the comparison must reflect what happens in the real world. Almost nobody consumes raw or processed tomatoes after completely removing the moisture. Therefore, the comparison should be made based on the actual consumption forms (wet weight). Fortunately, such comparisons were provided in 4 studies (42, 44, 46, 47) presented in Table 1. The data from these studies clearly show that, if consumed in the same amounts based on the wet weight, all compounds are much higher in the processed tomato pastes than in fresh tomatoes. This can be explained by the fact that tomato industrial processing is fundamentally a water-removal process. As an example, in 1 study (44), the ºBx of fresh tomatoes is 4.9 while it is 27.5 for tomato paste, suggesting that the total solids increased by over 5 times in paste. However, such a comparison may still not represent what happens in the real world. Most studies included in Table 1 were designed to answer the first question, and the tomato products produced in these studies were not commercial products. Besides, the compounds in tomato products were measured immediately after they were processed. Therefore, the impact of further processing, influence of other culinary ingredients, and the effects of storage were not considered.

Another important issue to compare the intake of nutrients and bioactive compounds between fresh tomatoes and processed tomato products is to recognize the dramatic difference between fresh consumed tomatoes and processing tomatoes. The US tomato processing industry is distinctly separate from the fresh-market industry in several ways. First, almost all processing tomatoes are cultivars of plum tomatoes, which were bred to obtain certain traits that make them specifically suitable for processing. Fresh-market tomatoes, by contrast, contain a wide range of varieties of tomatoes, and they differ greatly between one another in terms of size, shape, color, total solid, and other physicochemical and sensory properties. Second, processing tomatoes are harvested at the fully ripe stage, but fresh-market tomatoes are mostly picked green. Third, processing tomatoes are processed a few hours after they are harvested, whereas the fresh-market tomatoes usually take days or weeks to reach consumers’ hands after ripening, processing, transportation, and storage. Nutrients and bioactive compounds in fresh tomatoes vary extensively depending on the variety, cultivar, harvest time, ripening stage, and storage. As illustrated in 1 study, total lycopene in 1 fresh-consumed tomato cultivar (Pera) ranged from 0.39 mg/kg at the green stage, to 21.25 mg/kg at the breaker stage (when the pink color first becomes noticeable), to 40.95 mg/kg at the pink stage, and finally to 141.32 mg/kg at the red stage (28). To answer the second question, a comparison must be made between major types of fresh-consumed tomatoes and processed tomato products that are accessed by general consumers.

In the United States, currently such comparison can be made based on the data in USDA SR Legacy (36), which is now part of the USDA FoodData Central (https://fdc.nal.usda.gov/). The nutrient data presented in SR Legacy were obtained from the samples collected on the market in the United States. The comparisons of major nutrients and bioactive compounds among different raw tomatoes and processed tomato products are shown in Table 2. Overall, lycopene and vitamin E are much higher in most tomato products than in raw tomatoes, as they were both shown to be thermally stable (38, 51). Potassium is slightly higher in tomato products due to the combined effects of the loss during processing and the effect of concentration. Vitamin C, folate, and β-carotene are known to be unstable during thermal treatments. Consequently, their concentrations are generally lower in tomato products than in raw tomatoes. Remarkably, the content of α-carotene in all tomato products except for paste is zero. In a recent study, when comparing between different carotenoids and vitamin C, α-carotene was found to be the most thermolabile in the thermally treated tree tomato juice (64).

TABLE 2.

Nutrient composition in selected raw tomatoes and tomato products from USDA SR-Legacy1

| Nutrients | Raw red | Raw green | Raw orange | Raw yellow | Purée | Paste | Crushed | Sauce | Catsup | Juice | Soup |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin C, mg/100 g | 13.7 | 23.4 | 16 | 9 | 10.6 | 21.9 | 9.2 | 7 | 4.1 | 12.6 | 12.9 |

| Lycopene, μg/100 g | 2573 | 0 (AZ) | NA | NA | 21,754 | 28,764 | 5106 | 13,895 | 12,062 | 2537 | 10,920 |

| α-Carotene, μg/100 g | 101 | 78 | NA | NA | 0 | 29 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| β-Carotene, μg/100 g | 449 | 346 | NA | NA | 306 | 901 | 129 | 259 | 316 | 245 | 235 |

| Folate, μg/100 g | 15 | 9 | 29 | 30 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 0 |

| Vitamin A, IU/100 g | 833 | 642 | 1496 | 0 | 510 | 1525 | 215 | 435 | 527 | 408 | 392 |

| Vitamin E,2 mg/100 g | 0.54 | 0.38 | NA | NA | 1.97 | 4.3 | 1.25 | 1.44 | 1.46 | 0.59 | 0.34 |

| Potassium, mg/100 g | 237 | 204 | 212 | 258 | 439 | 1014 | 293 | 297 | 281 | 191 | 562 |

Data are expressed based on the weight of the consumption forms. Full description of raw tomatoes and tomato products: Raw red: Tomatoes, red, ripe, raw, year round average; Raw green: Tomatoes, green, raw; Raw orange: Tomatoes, orange, raw; Raw yellow: Tomatoes, yellow, raw; Purée: Tomato products, canned, purée, without salt added; Paste: Tomato products, canned, paste, without salt added; Crushed: Tomatoes, crushed, canned; Sauce: Tomato sauce, canned, no salt added; Catsup: catsup; Juice: Tomatoes, red, ripe, canned, packed in tomato juice; Soup: Soup, tomato, canned, condensed. AZ, assume zero; NA, not available; USDA SR-Legacy, USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference Legacy.

Measured as α-tocopherol.

Basically, there is no easy answer to the second question due to several reasons. First, there are many different varieties of freshly consumed tomatoes. The nutrient profiles differ widely among different varieties. Second, there are many different processed tomato products. The nutrient profiles of these different products, due to the different processing methods/conditions and the tomatoes, also varied considerably from one another. Third, studies have shown that industrial processing had different effects on different nutrients in different tomato products. Considering all these 3 factors, the best answer would be as follows: when consumed in the same amounts, some compounds (e.g., lycopene) are generally higher in processed tomatoes (not all processed tomatoes), while other compounds (e.g., α-carotene) are generally higher in fresh tomatoes (again, not all fresh tomatoes). In another words, the intake of a selected nutrient or bioactive compound is not necessarily greater or less from fresh unprocessed tomatoes than from a processed tomato product.

Limitation and research needs

Data in USDA SR Legacy have been frequently cited in many papers as a “gold standard” when comparing nutrient composition between raw tomatoes and processed tomato products (11, 29). However, the nutrient composition data in the current SR Legacy, released 2018, present shortfalls:

Only a single mean value was produced for each nutrient. This type of data expression does not allow the determination of variability in nutrient profiles.

The data on certain nutrients in the same foods are not current.

Not all data are experimentally measured data.

Sample sizes of many nutrients in all raw tomatoes and many tomato products are small (<3) or not available; therefore, the data were underrepresentative.

To make nutrient composition comparisons between raw and processed tomato products more meaningful, up-to-date nutrient composition data on commonly consumed fresh tomatoes and processed tomato products must be obtained. And the data should reflect the variation in nutrients and bioactive compounds influenced by various genetic and environmental factors. Currently, Foundation Foods, the new food-composition data type in the USDA FoodData Central system, aims to provide the specific data points behind the mean values, including the number of samples, location of harvest or procurement, and concurrent dates of acquisition, analytical methods, and agricultural information such as cultivar and production practices. The transparency of these data will allow users to see contributions to the variability of the component.

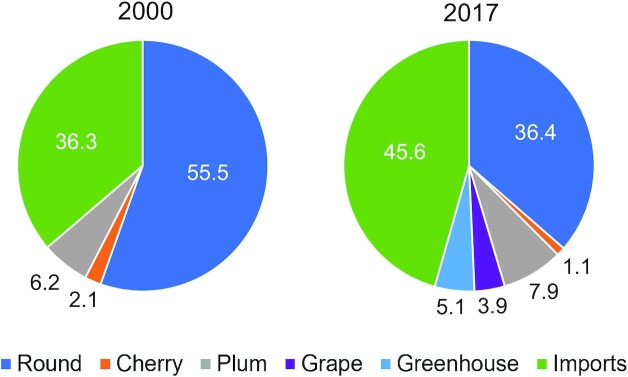

With regard to the nutrient data on fresh tomatoes, it is important to recognize the market changes and include the samples that represent the current consumption pattern. The fresh-market tomato sector has evolved to provide more specialized and globally sourced offerings for US consumers in the last 2 decades (65). Compared with the market in 2000, the percentages of round tomatoes and imported tomatoes declined in 2017, and greenhouse tomatoes and grape tomatoes have become important fractions (Figure 3). In particular, the rapid growth of the North American greenhouse tomato industry has made them more integrated into the mainstream fresh tomato industry, rather than a separate niche. Tomato production can be largely divided into open-field and protected agriculture. Protected agriculture [generally referred to as controlled environment agriculture (CEA)] refers to a wide category of production methods providing some degree of control over various environmental factors (66). The growers of greenhouse tomatoes can choose different structures of protected agriculture practice from simple shade-house to high-technology greenhouses, depending on the budget, type of protection, the degree of environmental control, and whether to grow in soil or use hydroponics. Greenhouse tomatoes are grown under different conditions and are exposed to fewer environmental challenges compared with open-field tomatoes. These characteristics will inevitably impact their nutrient compositions. At this point, the complete nutrient information for greenhouse tomatoes is lacking.

FIGURE 3.

Shift in freshly consumed tomato market in the United States from 2000 to 2017. Data from reference 65.

Additional Considerations

In addition to the 2 questions addressed above, several other important factors specifically related to the industrial processing of tomatoes must also be considered. These factors profoundly impact the “nutritious value” of processed tomatoes when comparing with fresh tomatoes.

For nutrients and bioactive compounds to be effective for human health, they must be absorbed in the digestive tract. The proportion of the ingested compounds that are delivered to the bloodstream for their intended mode of action, referred to as bioavailability, is more important than the total amount present in the original food (67). To be available for absorption, intracellular compounds must pass through the physical barrier represented by the cell wall. Disruption of the natural matrix or the microstructure of tomatoes during food processing may influence the release, transformation, and subsequent absorption of the nutrients and bioactive compound in the digestive tract (68). For instance, in raw tomatoes, the crystalline aggregation and location in the chromoplast make the all-trans form of lycopene poorly bioavailable (53). Industrial processing can destroy the cellular walls and dissociation of lycopene's crystalline aggregates, which allows lycopene to become more bioavailable during intestinal digestion and absorption (69–71). As a result, it has been repeatedly shown that lycopene bioavailability is higher for tomato products, such as tomato paste, purée, and sauce, than raw tomatoes (69, 70, 72). In addition, isomerization of carotenoids causes significant alteration in their bioavailability (35, 73). Studies suggested preferential absorption for cis-isomers of lycopene compared with the all-trans configuration (35, 74). In 1 study, while the primary geometric lycopene isomer in tomato products was all-trans (80–90%), plasma and prostate isomers were 47% and 80% cis-isomers, respectively, demonstrating a shift towards cis accumulation (72). On the contrary, data from several in vitro and in vivo tests have indicated that cis-isomers of β-carotene are less bioavailable than the all-trans-isomer (75). Food processing is also known to affect the bioavailability of phenolic compounds. While food processing often induces the degradation of phenolic compounds, it can lead to chemical or physical modifications in food in such a way that fosters the release and absorption of phenolic compounds during digestion (76, 77). In a randomized controlled trial, mechanical and heat treatments applied during tomato sauce production were found to enhance the plasma concentration and urinary excretion of naringenin glucuronide (78).

During industrial processing, some parts of tomatoes, including skin, seeds, and pulp, are removed as byproducts. This means that some valuable functional compounds may be lost in the finished product. As an example, tomato pomace is a major byproduct of tomato processing. It consists of peel and seeds and represents approximately 4% of the fruit weight (79). Chemical analysis revealed that tomato pomace contains mainly dietary fiber, proteins, and fat, as well as a fair amount of bioactive compounds including carotenoids and flavonoids (80, 81). Studies have found that tomato pomace showed certain bioactivities, such as inhibitory activity of platelet aggregation (82) and reduced hepatic total cholesterol content (83).

Most tomato products are not just tomatoes. When tomatoes are processed into different end products, various ingredients are added for different purposes. For example, to control the heating-related softening of the tomatoes, calcium is typically added at can filling. Sugar may be added to offset the tartness and sodium chloride is frequently added for taste. Several culinary ingredients are usually added for better taste and flavor. Interactions and effects of the added ingredients/compounds and their impact on the health effects of processed tomato products need to be considered. For instance, dietary fat, which is usually added to tomato products such as tomato sauce or pizza sauce, enhances carotenoid absorption (53). However, calcium was found to impair lycopene bioavailability in healthy humans (84).

Closing Remarks

“Are processed tomato products as nutritious as fresh tomatoes?” may not be an appropriate question to ask because the answer is dependent on so many factors, such as the types of fresh tomatoes, tomato products to be compared, and the ways to analyze and interpret the data. A simple “yes” or “no” answer to this question may be misleading. Answers to this question based on comparing certain fresh tomatoes and tomato products, or merely focusing on certain components (e.g., lycopene), would be misrepresentative. At this point, there are not sufficient data to fully understand all the factors and their impact on the nutrients and bioactive compounds in processed tomatoes. More research is warranted to fill the knowledge gap, and to keep up with the new development of tomato cultivars and the advancement of industrial processing technology.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors’ responsibilities were as follow—XW, LY, and PRP: designed the study and wrote the manuscript; XW: performed the systematic literature review and data analysis; and all authors: read and approved the final manuscript.

Notes

Supported by the USDA, Agricultural Research Service.

Author disclosures: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Mention of trade names or commercial products in this publication is solely for the purpose of providing specific information and does not imply recommendation or endorsement by the USDA.

Contributor Information

Xianli Wu, Methods and Application of Food Composition Laboratory, USDA, Agricultural Research Service, Beltsville Human Nutrition Research Center, Beltsville, MD, USA.

Liangli Yu, Department of Nutrition and Food Science, University of Maryland, College Park, MD, USA.

Pamela R Pehrsson, Methods and Application of Food Composition Laboratory, USDA, Agricultural Research Service, Beltsville Human Nutrition Research Center, Beltsville, MD, USA.

References

- 1. Slavin JL, Lloyd B. Health benefits of fruits and vegetables. Adv Nutr. 2012;3:506–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Boeing H, Bechthold A, Bub A, Ellinger S, Haller D, Kroke A, Leschik-Bonnet E, Müller MJ, Oberritter H, Schulze M et al. Critical review: vegetables and fruit in the prevention of chronic diseases. Eur J Nutr. 2012;51:637–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hung HC, Joshipura KJ, Jiang R, Hu FB, Hunter D, Smith-Warner SA, Colditz GA, Rosner B, Spiegelman D, Willett WC. Fruit and vegetable intake and risk of major chronic disease. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:1577–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Canene-Adams K, Campbell JK, Zaripheh S, Jeffery EH, Erdman JW Jr. The tomato as a functional food. J Nutr. 2005;135:1226–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dwyer JT, Fulgoni VL 3rd, Clemens RA, Schmidt DB, Freedman MR. Is “processed” a four-letter word? The role of processed foods in achieving dietary guidelines and nutrient recommendations. Adv Nutr. 2012;3:536–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jin H, Lu Y. Evaluating consumer nutrition environment in food deserts and food swamps. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:2675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Miller SR, Knudson WA. Nutrition and cost comparisons of select canned, frozen, and fresh fruits and vegetables. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2014;8:430–7. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Floros JD, Newsome R, Fisher W, Barbosa-Cánovas GV, Chen H, Dunne CP, German JB, Hall RL, Heldman DR, Karwe MV et al. Feeding the world today and tomorrow: the importance of food science and technology: an IFT scientific review. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2010;9:572–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kapica C. Do canned foods fit today's dietary needs?. Nutr Today. 2013;48:161–4. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rickman JC, Barrett DM, Bruhn CM. Nutritional comparison of fresh, frozen and canned fruits and vegetables. Part 1. Vitamins C and B and phenolic compounds. J Sci Food Agric. 2007;87:930–44. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rickman JC, Bruhn CM, Barrett DM. Nutritional comparison of fresh, frozen, and canned fruits and vegetables II. Vitamin A and carotenoids, vitamin E, minerals and fiber. J Sci Food Agric. 2007;87:1185–96. [Google Scholar]

- 12. McClements DJ, Vega C, Mcbride AE, Decker EA. In defense of food science. Gastronomica. 2011;11:76–84. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Weaver CM, Dwyer J, Fulgoni VL 3rd, King JC, Leveille GA, MacDonald RS, Ordovas J, Schnakenberg D. Processed foods: contributions to nutrition. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;99:1525–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. van Boekel M, Fogliano V, Pellegrini N, Stanton C, Scholz G, Lalljie S, Somoza V, Knorr D, Jasti PR, Eisenbrand G. A review on the beneficial aspects of food processing. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2010;54:1215–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Reimers KJ, Keast DR. Tomato consumption in the United States and its relationship to the US Department of Agriculture food pattern: results from What We Eat in America 2005–2010. Nutr Today. 2016;51:198–205. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Agricultural Marketing Resource Center . Tomatoes. [Internet]. 2018. Available from: https://www.agmrc.org/commodities-products/vegetables/tomatoes. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Beecher GR. Nutrient content of tomatoes and tomato products. Exp Biol Med. 1998;218:98–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Garcia E, Barrett DM. Evaluation of processing tomatoes from two consecutive growing seasons: quality attributes, peelability and yield. J Food Process Preserv. 2006;30:20–36. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Thakur BR, Singh RK, Nelson PE. Quality attributes of processed tomato products: a review. Food Rev Int. 1996;12:375–401. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Clinton SK. Lycopene: chemistry, biology, and implications for human health and disease. Nutr Rev. 1998;56:35–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Khachik F, Carvalho L, Bernstein PS, Muir GJ, Zhao DY, Katz NB. Chemistry, distribution, and metabolism of tomato carotenoids and their impact on human health. Exp Biol Med. 2002;227:845–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Martí R, Roselló S, Cebolla-Cornejo J. Tomato as a source of carotenoids and polyphenols targeted to cancer prevention. Cancers. 2016;8:58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Perveen R, Suleria HA, Anjum FM, Butt MS, Pasha I, Ahmad S. Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) carotenoids and lycopenes chemistry; metabolism, absorption, nutrition, and allied health claims—a comprehensive review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2015;55:919–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Shi J, Le Maguer M. Lycopene in tomatoes: chemical and physical properties affected by food processing. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2000;20:293–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Siddiqui MW, Ayala-Zavala JF, Dhua RS. Genotypic variation in tomatoes affecting processing and antioxidant attributes. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2015;55:1819–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Honda M, Murakami K, Watanabe Y, Higashiura T, Fukaya T, Wahyudiono K H, Goto M. The E/Z isomer ratio of lycopene in foods and effect of heating with edible oils and fats on isomerization of (all-E)-lycopene. Eur J Lipid Sci Technol. 2017;119:1600389. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Martínez-Hernández GB, Boluda-Aguilar M, Taboada-Rodríguez A, Soto-Jover S, Marín-Iniesta F, López-Gómez A. Processing, packaging, and storage of tomato products: influence on the lycopene content. Food Eng Rev. 2016;8:52–75. [Google Scholar]

- 28. García-Valverde V, Navarro-González I, García-Alonso J, Periago MJ. Antioxidant bioactive compounds in selected industrial processing and fresh consumption tomato cultivars. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2013;6:391–402. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chaudhary P, Sharma A, Singh B, Nagpal AK. Bioactivities of phytochemicals present in tomato. J Food Sci Technol. 2018;55:2833–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Martí R, Leiva-Brondo M, Lahoz I, Campillo C, Cebolla-Cornejo J, Roselló S. Polyphenol and L-ascorbic acid content in tomato as influenced by high lycopene genotypes and organic farming at different environments. Food Chem. 2018;239:148–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Barringer SA. Vegetables: tomato processing. In: Smith JS, Hui YH, editors. Food processing: principles and applications. 1st ed. Ames (IA): Blackwell Publishing; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kamiloglu S, Boyacioglu D, Capanoglu E. The effect of food processing on bioavailability of tomato antioxidants. J Berry Res. 2013;3:65–77. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O'Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, Moher D, Peters MDJ, Horsley T, Weeks L et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:467–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Capanoglu E, Beekwilder J, Boyacioglu D, De Vos RC, Hall RD. The effect of industrial food processing on potentially health-beneficial tomato antioxidants. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2010;50:919–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Saini RK, Bekhit AEDA, Roohinejad S, Rengasamy KRR, Keum YS. Chemical stability of lycopene in processed products: a review of the effects of processing methods and modern preservation strategies. J Agric Food Chem. 2020;68:712–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Haytowitz DB, Ahuja JKC, Wu X, Somanchi M, Nickle M, Nguyen QA, Roseland JM, Williams JR, Patterson KY, Li Y et al. USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference. [Internet]. 2019; [cited 2020 Nov 16]. Legacy Release: Available from: https://data.nal.usda.gov/dataset/usda-national-nutrient-database-standard-reference-legacy-release. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Abushita AA, Daood HG, Biacs PA. Change in carotenoids and antioxidant vitamins in tomato as a function of varietal and technological factors. J Agric Food Chem. 2000;48:2075–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Seybold C, Fröhlich K, Bitsch R, Otto K, Böhm V. Changes in contents of carotenoids and vitamin E during tomato processing. J Agric Food Chem. 2004;52:7005–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Georgé S, Tourniaire F, Gautier H, Goupy P, Rock E, Caris-Veyrat C. Changes in the contents of carotenoids, phenolic compounds and vitamin C during technical processing and lyophilisation of red and yellow tomatoes. Food Chem. 2011;124:1603–11. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lopez A, Williams HL. Essential elements in fresh and canned tomatoes. J Food Sci. 1981;46:432–4. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Abdel-Rahman A-HY. Nutritional value of some canned tomato juice and concentrates. Food Chem. 1982;9:303–6. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Takeoka GR, Dao L, Flessa S, Gillespie DM, Jewell WT, Huebner B, Bertow D, Ebeler SE. Processing effects on lycopene content and antioxidant activity of tomatoes. J Agric Food Chem. 2001;49:3713–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Chanforan C, Loonis M, Mora N, Caris-Veyrat C, Dufour C. The impact of industrial processing on health-beneficial tomato microconstituents. Food Chem. 2012;134:1786–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Koh E, Charoenprasert S, Mitchell AE. Effects of industrial tomato paste processing on ascorbic acid, flavonoids and carotenoids and their stability over one-year storage. J Sci Food Agric. 2012;92:23–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Capanoglu E, Beekwilder J, Boyacioglu D, Hall R, de Vos R. Changes in antioxidant and metabolite profiles during production of tomato paste. J Agric Food Chem. 2008;56:964–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Jacob K, Garcia-Alonso FJ, Ros G, Periago MJ. Stability of carotenoids, phenolic compounds, ascorbic acid and antioxidant capacity of tomatoes during thermal processing. Arch Latinoam Nutr. 2010;60:192–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Re R, Bramley PM, Rice-Evans C. Effects of food processing on flavonoids and lycopene status in a Mediterranean tomato variety. Free Radic Res. 2002;36:803–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Tomas M, Beekwilder J, Hall RD, Sagdic O, Boyacioglu D, Capanoglu E. Industrial processing versus home processing of tomato sauce: effects on phenolics, flavonoids and in vitro bioaccessibility of antioxidants. Food Chem. 2017;220:51–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Barrett DM, Weakley C, Diaz JV, Watnik M. Qualitative and nutritional differences in processing tomatoes grown under commercial organic and conventional production systems. J Food Sci. 2007;72:C441–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Barrett DM, Lloyd B. Advanced preservation methods and nutrient retention in fruits and vegetables. J Sci Food Agric. 2012;92:7–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Colle I, Lemmens L, Van Buggenhout S, Van Loey A, Hendrickx M. Effect of thermal processing on the degradation, isomerization, and bioaccessibility of lycopene in tomato pulp. J Food Sci. 2010;75:C753–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Arballo J, Amengual J, Erdman JW Jr. Lycopene: a critical review of digestion, absorption, metabolism, and excretion. Antioxidants. 2021;10:342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. D'Evoli L, Lombardi-Boccia G, Lucarini M. Influence of heat treatments on carotenoid content of cherry tomatoes. Foods. 2013;2:352–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Nguyen ML, Schwartz SJ. Lycopene stability during food processing. Exp Biol Med. 1998;218:101–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Erdman JW, Klein BP. Harvesting, processing, and cooking influences on vitamin C in foods. In: Ascorbic acid: chemistry, metabolism, and uses. Washington (DC): American Chemical Society; 1982. p. 499–532. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Ahmed M, Eun JB. Flavonoids in fruits and vegetables after thermal and nonthermal processing: a review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2018;58:3159–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Nayak B, Liu RH, Tang J. Effect of processing on phenolic antioxidants of fruits, vegetables, and grains—a review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2015;55:887–918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Huang D, Ou B, Prior RL. The chemistry behind antioxidant capacity assays. J Agric Food Chem. 2005;53:1841–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Pękal A, Pyrzynska K. Evaluation of aluminium complexation reaction for flavonoid content assay. Food Anal Methods. 2014;7:1776–82. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Prior RL, Wu X, Schaich K. Standardized methods for the determination of antioxidant capacity and phenolics in foods and dietary supplements. J Agric Food Chem. 2005;53:4290–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Huang R, Wu W, Shen S, Fan J, Chang Y, Chen S, Ye X. Evaluation of colorimetric methods for quantification of citrus flavonoids to avoid misuse. Anal Methods. 2018;10:2575–87. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Xu Q, Adyatni I, Reuhs B. Effect of processing methods on the quality of tomato products. Food Nutr Sci. 2018;9:86–98. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Anthon GE, LeStrange M, Barrett DM. Changes in pH, acids, sugars and other quality parameters during extended vine holding of ripe processing tomatoes. J Sci Food Agric. 2011;91:1175–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Ordóñez-Santos LE, Martínez-Girón J. Thermal degradation kinetics of carotenoids, vitamin C and provitamin A in tree tomato juice. Int J Food Sci Technol. 2020;55:201–10. [Google Scholar]

- 65. Baskins S, Bond J, Minor T. Unpacking the growth in per capita availability of fresh market tomatoes. Washington (DC): USDA; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 66. Cook R, Calvin L. Greenhouse tomatoes change the dynamics of the North American fresh tomato industry. USDA Economic Research Report Number 2. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 67. Sensoy I. A review on the relationship between food structure, processing, and bioavailability. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2014;54:902–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Parada J, Aguilera JM. Food microstructure affects the bioavailability of several nutrients. J Food Sci. 2007;72:R21–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Gärtner C, Stahl W, Sies H. Lycopene is more bioavailable from tomato paste than from fresh tomatoes. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;66:116–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Stahl W, Sies H. Uptake of lycopene and its geometrical isomers is greater from heat-processed than from unprocessed tomato juice in humans. J Nutr. 1992;122:2161–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. van het Hof KH, de Boer BC, Tijburg LB, Lucius BR, Zijp I, West CE, Hautvast JG, Weststrate JA. Carotenoid bioavailability in humans from tomatoes processed in different ways determined from the carotenoid response in the triglyceride-rich lipoprotein fraction of plasma after a single consumption and in plasma after four days of consumption. J Nutr. 2000;130:1189–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Grainger EM, Hadley CW, Moran NE, Riedl KM, Gong MC, Pohar K, Schwartz SJ, Clinton SK. A comparison of plasma and prostate lycopene in response to typical servings of tomato soup, sauce or juice in men before prostatectomy. Br J Nutr. 2015;114:596–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Takehara M, Nishimura M, Kuwa T, Inoue Y, Kitamura C, Kumagai T, Honda M. Characterization and thermal isomerization of (all-E)-lycopene. J Agric Food Chem. 2014;62:264–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Boileau TW, Boileau AC, Erdman JW Jr. Bioavailability of all-trans and cis-isomers of lycopene. Exp Biol Med. 2002;227:914–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Honda M, Maeda H, Fukaya T, Goto M. Effects of Z-isomerization on the bioavailability and functionality of carotenoids: a review. In: Zepka LQ, Jacob-Lopes E, De Rosso VV, editors. Progress in carotenoid research. London (UK): IntechOpen; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 76. Ribas-Agustí A, Martín-Belloso O, Soliva-Fortuny R, Elez-Martínez P. Food processing strategies to enhance phenolic compounds bioaccessibility and bioavailability in plant-based foods. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2018;58:2531–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Arfaoui L. Dietary plant polyphenols: effects of food processing on their content and bioavailability. Molecules. 2021;26:2959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Martínez-Huélamo M, Tulipani S, Estruch R, Escribano E, Illán M, Corella D, Lamuela-Raventós RM. The tomato sauce making process affects the bioaccessibility and bioavailability of tomato phenolics: a pharmacokinetic study. Food Chem. 2015;173:864–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Del Valle M, Cámara M, Torija M-E. Chemical characterization of tomato pomace. J Sci Food Agric. 2006;86:1232–6. [Google Scholar]

- 80. Palomo I, Concha-Meyer A, Lutz M, Said M, Sáez B, Vásquez A, Fuentes E. Chemical characterization and antiplatelet potential of bioactive extract from tomato pomace (byproduct of tomato paste). Nutrients. 2019;11:456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Silva PAY, Borba BC, Pereira VA, Reis MG, Caliari M, Brooks MS, Ferreira T. Characterization of tomato processing by-product for use as a potential functional food ingredient: nutritional composition, antioxidant activity and bioactive compounds. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2019;70:150–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Rodríguez-Azúa R, Treuer A, Moore-Carrasco R, Cortacáns D, Gutiérrez M, Astudillo L, Fuentes E, Palomo I. Effect of tomato industrial processing (different hybrids, paste, and pomace) on inhibition of platelet function in vitro, ex vivo, and in vivo. J Med Food. 2014;17:505–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Shao D, Bartley GE, Yokoyama W, Pan Z, Zhang H, Zhang A. Plasma and hepatic cholesterol-lowering effects of tomato pomace, tomato seed oil and defatted tomato seed in hamsters fed with high-fat diets. Food Chem. 2013;139:589–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Borel P, Desmarchelier C, Dumont U, Halimi C, Lairon D, Page D, Sébédio JL, Buisson C, Buffière C, Rémond D. Dietary calcium impairs tomato lycopene bioavailability in healthy humans. Br J Nutr. 2016;116:2091–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]