Abstract

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) remains one of the greatest public health concerns with increasing morbidity and mortality rates worldwide. Our group reported that stimulation of astrocyte mitochondrial metabolism by P2Y1 receptor agonists significantly reduced cerebral edema and reactive gliosis in a TBI model. Subsequent data on the pharmacokinetics (PK) and rapid metabolism of these compounds suggested that neuroprotection was likely mediated by a metabolite, AST-004, which binding data indicated was an adenosine A3 receptor (A3R) agonist. The neuroprotective efficacy of AST-004 was tested in a control closed cortical injury (CCCI) model of TBI in mice. Twenty-four (24) hours post-injury, mice subjected to CCCI and treated with AST-004 (0.22 mg/kg, injected 30 min post-trauma) exhibited significantly less secondary brain injury. These effects were quantified with less cell death (PSVue794 fluorescence) and loss of blood brain barrier breakdown (Evans blue extravasation assay), compared to vehicle-treated TBI mice. TBI-treated mice also exhibited significantly reduced neuroinflammatory markers, glial-fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP, astrogliosis) and ionized Ca2+-binding adaptor molecule 1 (Iba1, microgliosis), both at the mRNA (qRT-PCR) and protein (Western blot and immunofluorescence) levels, respectively. Four (4) weeks post-injury, both male and female TBI mice presented a significant reduction in freezing behavior during contextual fear conditioning (after foot shock). AST-004 treatment prevented this TBI-induced impairment in male mice, but did not significantly affect impairment in female mice. Impairment of spatial memory, assessed 24 and 48 h after the initial fear conditioning, was also reduced in AST-004-treated TBI-male mice. Female TBI mice did not exhibit memory impairment 24 and 48 h after contextual fear conditioning and similarly, AST-004-treated female TBI mice were comparable to sham mice. Finally, AST-004 treatments were found to increase in vivo ATP production in astrocytes (GFAP-targeted luciferase activity), consistent with the proposed mechanism of action. These data reveal AST-004 as a novel A3R agonist that increases astrocyte energy production and enhances their neuroprotective efficacy after brain injury.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13311-021-01113-7.

Keywords: ADORA3, Concussion treatment, Mitochondrial metabolism, ATP, Astrocytes

Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is defined as a shock, jolt or blow to the head [1]. It is one of the most common causes of disability and abnormal brain function, resulting from sport, battlefield, fall, and domestic violence injuries [2–5]. Roughly 19% of the 1.64 million soldiers deployed in the Iraq war suffered TBI events [3], and nearly 50% of ~42 million women in the United States subjected to domestic violence have suffered a TBI [2]. All TBIs increase the risk of developing neurodegenerative diseases including Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases [6]. Moreover, our group recently documented significant changes in the electrical properties of neurons after repetitive mild TBIs in a blunt mouse-TBI model [7]. There are no FDA-approved therapeutic treatments for TBI and its many associated sequelae, despite over 1000 clinical trials [8].

TBI severity can range from mild to severe, with mild TBIs being the most common type [6]. One of the challenges of studying TBI-mediated neuropathy is the duration over which injury progression occurs [6]. Progression is divided into two phases: an irreversible, primary phase of physical injury, caused by shearing, tearing or crushing of the brain [9], followed by a secondary phase of injury, occurring over hours to months later. The sequalae of the secondary injury, in principle, could be prevented or even reversed with treatment. Such sequelae include cerebral edema, a maladaptive inflammatory response, calcium (Ca2+) ion toxicity, epilepsy, and infection [9–12]. The focus of our study has been on testing the therapeutic efficacy of a potential new drug, AST-004, on the sequelae associated with the secondary phase of injury that acts via a novel mechanism.

Astrocytes and microglia are widely recognized for their central roles in maintaining brain health [13]. Normal functions of astrocytes include nutritional support to neurons, ion, and water homeostasis and regulation of synaptic function [13]. During stress or in response to injury, astrocytes play key neuroprotective roles. They undergo morphological and molecular changes, called astrogliosis [14]. Cytoskeletal hypertrophy and the upregulation of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) are key features [14]. Ultimately, if an injury cannot be healed, the wound is sealed off by the formation of glial scars [13, 14] to limit the spread of inflammation [15]. Microglia also undergo reactive gliosis after brain injury, indicated by upregulation of ionized Ca2+-binding adaptor molecule 1 (Iba1), and are critical for the removal of cellular and molecular debris, aiding in the restoration of normal brain environment [16]. In the long term, chronically activated microglia not only can release harmful pro-inflammatory molecules that are damaging, but can also work in conjunction with astrocytes to form a barrier around the injured site [17]. Both astrocytes and microglia play vital roles in the response to injury after TBI.

We previously reported that the P2Y1 receptor agonists, MRS2365 and 2MeS-ADP, exhibit significant neuroprotective efficacy after brain injuries in mouse models of ischemic stroke and TBI [18–20]. Our data indicated that both agonists increased mitochondrial energy (ATP) production in astrocytes, which in turn drove multiple natural protective processes (e.g., restoration of ion homeostasis, removal of extracellular glutamate, and production of growth factors and antioxidants). P2Y1 receptors are G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs), coupled to Gq/11 and phospholipase Cβ, whose activation induces inositol (1,4,5) tri-phosphate (IP3)-mediated Ca2+ release from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) [17, 21–23]. We demonstrated that astrocyte mitochondria partially sequestered this excess Ca2+, leading to increased ATP production [18–20].

We also revealed MRS2365 and 2MeSADP in mice to be rapidly metabolized into their respective nucleoside metabolites [24]. Pharmacokinetic studies demonstrated that MRS2365 was converted into AST-004 (MRS4322), whereas 2MeSADP was converted into 2-methylthioadenosine. We further demonstrated that both metabolites were adenosine receptor (AR) agonists, primarily for A3Rs, but also with some affinity for A1Rs [24]. Based on these data, we hypothesized that MRS2365 served as a prodrug and that in vivo neuroprotection against TBI and stroke was mediated by its nucleoside metabolite AST-004. Here, we demonstrate that intraperitoneal injections of AST-004 into mice subjected to TBI increased ATP production and decreased the severity of brain injuries. These data suggest a promising new therapeutic for the treatment of acute and long-term sequelae associated with TBIs.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Adenosine A3 receptor (A3R) agonist AST-004 was synthesized, in part, at the National Institute of Health (Bethesda, MD), as previously reported [25] and in part, was a gift of Astrocyte Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Unbound brain concentrations of AST-004 were determined following dosing using a specific LC/MS/MS assay [25]. Maximum unbound brain concentrations were measured at 5 ng/gm, demonstrating that AST-004 was distributed in the brain and available to interact with A3R.

Animals

Male and female C57BL/6 J mice (10 weeks old) were housed in 12 h light–dark cycles with food and water ad libitum. Animals were sorted prior to each experiment so that each cage included mice from all treatment groups. In total, 109 male and 34 female mice were used for these experiments. Numbers of mice per experiment are stated in each figure legend. During data collection, the experimenter was blinded to animal groups. All experiments were performed in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at UT Health San Antonio and were in compliance with the National Institutes of Health “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.”

Study Design

All studies were randomized and blinded. Experimental groups were tested throughout the day and analyzed in parallel. The timing of all experimental procedures, manipulations, and tests is presented in Fig. 1. Experiments were also repeated on different days a minimum of 3 times. Stock solutions were prepared on multiple separate occasions. The sample size for each experiment was determined by power analysis based upon pilot experiments. Mean group differences were set at p < 0.05 and a power of 0.8.

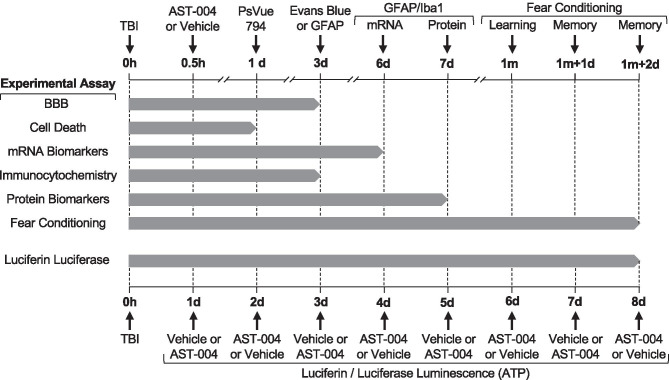

Fig. 1.

Gantt chart showing the timing of all experimental procedures, manipulations, and tests. Experimental assays for all the data presented in the figures for this study are listed in the left column. The timing of the procedures and measurements for each assay is indicated by the vertical-labeled arrows along the top horizontal axis. Note the top axis is interrupted at multiple points to show the time scale in hours (h), days (d), and months (m). The duration of each experimental assay is indicated by the length of the horizontal gray bars. The timing for luciferin/luciferase luminescence measurements is presented on the lower horizontal axis in days (d) post-TBI at 0 h. The duration of these experiments was 8 days, indicated by the horizontal gray bar. Note luminescence measurements alternated between vehicle and AST-004 in 24 h cycles

Traumatic Brain Injury Model

TBIs were induced using a control closed cortical impact (CCCI) model to simulate focal contusion with the skull intact as previously described [19]. Briefly, mice were placed in an anesthesia chamber, and anesthesia was induced with 4% isoflurane in a 2:1 mixture of N2O:O2 and maintained with 2% isoflurane in a 2:1 mixture of N2O:O2 [26]. In order to generate a mild-to-moderate TBI (without skull fracture or obvious hematomas), the pneumatic device (Leica Biosystems) was prepared with a 5 mm diameter cylinder probe to induce a 1 mm depth impact at 4.5 m/s velocity, positioned between the sagittal suture and coronal ridge with the borders near the lambda and bregma. Sham groups underwent the exact same procedures without the impact. TBI mice received a single TBI and were treated with either vehicle or AST-004 (intraperitoneal (IP) injection; 0.22 mg/kg) 30 min after insult.

Cell Death and Blood Brain Barrier Permeability

To visualize cell death in vivo, the infra-red fluorescent probe, PSVue794, was intravenously injected at a concentration of 3 mg/kg, 24 h post-CCCI according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Molecular Targeting). The probe was permitted to circulate for 48 h prior to measurements. The same group of mice was intravenously injected with Evans blue dye (2.5 mg/kg, Sigma Aldrich) 72 h after CCCI in order to examine blood brain barrier permeability. The dye was allowed to circulate 2 h prior to measurements, and a transcardial perfusion was performed to remove intravascular probe. Both PSVue794 and Evans blue signals were measured using a Xenogen IVIS Spectrum Imaging System. Imaging analysis was performed using Living Image Software 4.5.5 (Caliper Life Science). The regions of interest (ROIs) were located in the peri-injured site of each sample and the fluorescence values were recorded as radiant efficiency (emission light (photons/s/cm2/steradian)/excitation light (μW/cm2)).

Immunohistochemistry, Image Acquisition and Analysis

IHC was performed 72 h after CCCI. Mice were euthanized via transcardial perfusion with PBS and 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA, Electron Microscopy Sciences). Brains were removed, further fixed overnight in 4% PFA, transferred into 30% (w/v) sucrose and kept at 4 °C for 3 days. Brains were then embedded into histology molds (TedPella) filled with Tissue-Plus O.C.T. compound (Fisher Scientific), rapidly frozen with 2-methylbutane immersed in liquid N2 and stored at −80 °C until cryosectioning. Thirty-micron thick coronal sections were cut using a HM505E Cryostat (MICROM International) and mounted on previously gelatin (Sigma)-coated Superfrost Plus Microscope Slides (Fisher Scientific), and dried overnight. Sections were rehydrated with PBS, and their immunoreactivity was enhanced via heat-induced antigen retrieval using a DIVA decloaker (Biocare Medical). Slides were then washed with PBS twice for 5 min and dipped into 0.25% (v/v) Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich) for another 10 min. Following two more PBS washes, sections were blocked with 5% (v/v) bovine serum albumin (Sigma) for 1 h at RT, excess blocking solution was removed, and slices were incubated with primary antibodies (1:1000 GFAP, Abcam ab53554) at 4 °C for 20 h. The following day, sections were washed with PBS 5 × for 15 min periods and incubated in secondary antibodies (1:200 Thermo Fisher Lot# 1,640,316 donkey anti-goat Alexa Fluor 568) for 1 h at RT. Sections were then washed 3 × for 5 min/each and further incubated in DAPI (Sigma) for 10 min. After a brief wash in distilled H2O, brain sections were mounted with a Vectashield antifade-mounting medium (Vector Laboratories). All slides were imaged using a Zeiss LSM710 confocal microscope (40 × magnification, NA 1.3) in the Core Optical Imaging Facility at UT Health SA. Fluorescence settings and parameters were held constant for all sections. Z stacks at 1-µm intervals were processed using ImageJ (Wayne Rasband, National Institutes of Health, USA). Custom macros in ImageJ were used to quantify mean fluorescence intensity analysis. In short, maximum intensity projections were first generated from Z-stacked images. Background fluorescence was removed using the stack-based spots plug-in from ICBM (Indiana Center for Biological Microscopy) to mask cells. Mean gray values were calculated and used for the analysis.

Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction

qRT-PCR samples were collected 6 days after CCCIs, snap frozen in dry ice, and stored at −80 °C until analysis. Mouse brains were bathed in an ice-cold Ringer’s solution and maintained over ice during dissection of cortical samples. Cortical samples were composed of 2 mm × 2 mm squares dissected between the rostral and middle branches of the superior sagittal sinus, visible by eye. The 1 mm × 2 mm2 cube-shaped sample volume contained all cortical layers. Contralateral and ipsilateral cortical samples were collected separately. An Ultra EZgrind tissue homogenizer (Denville Scientific) was used at the lowest speed (5000 rpm) to homogenize samples in a TRIzol buffer (Life). After chloroform extraction, total RNA was precipitated with isopropyl alcohol and resuspended in nuclease-free water. A spectrophotometer (Nanodrop) was used to test RNA quality and quantity. Eight hundred ng of total RNA, from each sample, was used for cDNA synthesis. Synthesis was performed with Oligo(dT)20 primers (Invitrogen) and SuperScript III first-strand reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen), following manufacturer protocol. Samples were run in triplicates for each primer. The primers used were GFAP: F- TGCGTATAGACAGGAGGCAGATGAAG, R- GGAGTTCTCGAACTTCCTCCTCATAG; IBA1: F- GGGGATCAACAAGCAATTCCTCGA, R- ACTCCATGTACTTCACCTTGAAGGC; GAPDH: F- GAAGGGCTCATGACCACAGTCC, R- CCACGGCCATCACGCCACAG. The amplicons obtained were run in agarose gel by electrophoresis, and the presence of one specific band from the predicted size was visualized, confirming primer specificity. GAPDH was used as a housekeeping gene for normalization of Iba1 and GFAP results. To test if GAPDH was a suitable housekeeping gene for our experiments, we confirmed that CCCI and/or AST-004 treatment did not cause a significant change in GAPDH expression (Fig. 3d, h). Hypoxanthine–guanine phosphoribosyltransferase (HPRT) was used as a housekeeping gene for this test. Optimum sample dilution was determined by equal amplification efficiency of the gene of interest and GAPDH over a range of dilutions (80–5120 ×). To define the best concentration of forward and reverse primers for all the genes of interest and GAPDH, different primer dilutions were tested against a sham sample and water. The number of cycles necessary to use all the substrate in a reaction with the test sample was subtracted from the number of cycles obtained with ddH2O. The larger the difference in the number of cycles, the higher the efficiency and specificity of the reaction. The same procedure was performed throughout our experiments to determine the best concentrations of forward and reverse primers in each set of qRT-PCR reactions executed. All qRT-PCR reactions were performed in a 7900 HT Fast Real-Time PCR system (Life Technologies) using SYBR Green PCR master mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The reactions started with one-step of 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 1 min. The number of cycles needed to reach exhaustion of the reaction, threshold cycle (CT), was determined. The difference between template CT and housekeeping gene CT (ΔCT) was calculated and transformed using a power of 2. The results were normalized to the average of sham ipsilateral samples and are presented as mean and S.E.M. for each group.

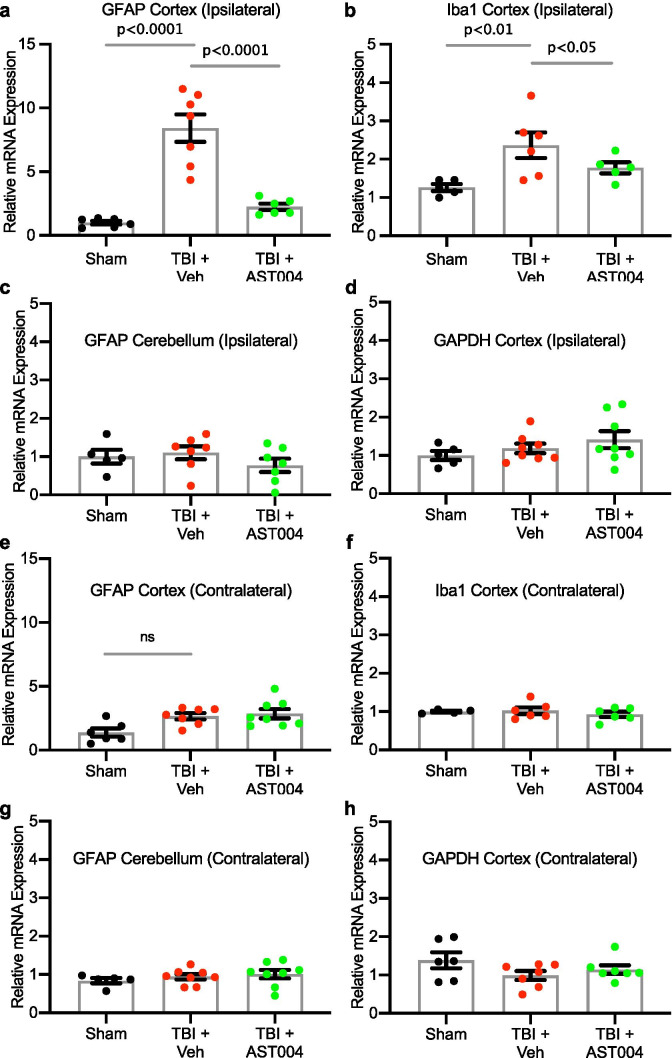

Fig. 3.

TBI-induced increases in mRNA levels of GFAP and Iba1 in the cortex are reduced by AST-004 treatments. Mice underwent sham or TBI and received AST-004 treatment (0.22 mg/kg) or vehicle 30 min post-injury. qRT-PCRs of brain homogenates were performed 7 days post-injury. mRNA levels for GFAP and Iba1 in the ipsilateral cortex are shown in histogram plots, as labeled a, b. GFAP mRNA levels in the ipsilateral cerebellum were not affected by TBI c GAPDH mRNA levels in the ipsilateral cortex were also unaffected d. For comparison, contralateral mRNA levels for GFAP, Iba1, and GAPDH in the cortex and GFAP in the cerebellum are also not significantly different in TBI-induced brain samples e, h. Number of mice used for sham: 3 males and 3 females, for TBI + vehicle: 3 males and 5 females, for TBI + AST-004: 5 males and 3 females. All samples run in duplicate. Brain samples from the contralateral side of the brain to the site of injury did not exhibit changes in mRNA levels for GFAP (cortex and cerebellum), Iba1 or GAPDH either after TBI only or TBI + AST-004 treatment AQ8(Fig. 3e–h)

Western Blotting

The right (ipsilateral) and left (contralateral) brain hemispheres as well as plasma samples were collected 7 days post-injury, and immediately snap frozen in dry ice. Protein extracts were prepared by homogenizing frozen samples on ice in a RIPA buffer solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific — 89,901), which included protease inhibitor tablet (Roche — 05,892,988,001), phosphatase inhibitor cocktail 2 (Sigma — P5726), and cocktail 3 (Sigma — P0044). An Ultra EZgrind tissue homogenizer (Denville Scientific Inc.) was used at the lowest speed. The protein concentration of each sample was determined with a Pierce BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific — 23,225). Protein extracts were reduced, denatured, and samples (25 µg of total protein) run (130 V for ~1 h) in 4–20% precast polyacrylamide gels (Bio-Rad — 4,561,096). Proteins were transferred for 1 h at 100 V to a nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad — 10,484,060). GFAP antibody (Abcam — ab53554) was used at a dilution of 1:1000, while Actin antibody (Sigma — A2228) was used at a dilution of 1:10,000. To reveal immunoblot bands, a chemiluminescent reaction between horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:5000 Jackson Laboratories) and Western Lightning Plus-ECL reagents (PerkinElmer — NEL105001EA) was used. ImageJ software (FIJI, Gel Analyzer) was used to quantify bands after exposure in the linear range. Proteins were normalized by the housekeeping protein β-actin.

Contextual Fear Conditioning

Contextual fear conditioning–behavior assay was performed to assess spatial memory function [27–29]. Before the experiments were performed, all mice were handled by the experimenter for 1 min during 5 consecutive days preceding testing at 1 month for habituation. During training sessions, mice were placed in the conditioning box (25.3 cm × 25.4 cm × 18.5 cm) and allowed to freely explore the box for 2 min. After initial exploration, three consecutive foot shocks separated by 1-s intervals were administered. Each shock (0.5 mA) was 2 s in duration. Mice were left in the chamber for 50 s in order to associate the chamber with the shocks. Overall, the training session was 3 min long, and freezing time was quantified after the shocks. To assess long-term memory, 2 min-long memory tests were conducted 24 and 48 h after the initial training session. The percent of freezing time during a memory test was recorded as the primary readout. Time spent freezing was quantified automatically by a Freeze monitor (San Diego Instruments Inc). A mouse was considered freezing when it spent 2 s or more without any movements except for breathing-related movements.

In Vivo Bioluminescence Measurements of Luciferin–Luciferase

Transgenic mice expressing the Luciferase-reporter gene in astrocytes (Dual Glo, Jackson Laboratories) were housed until 3–4 months of age prior to measurements of bioluminescence with a Xenogen IVIS Imaging system. All mice received a single TBI 2–6 days prior to imaging in order to increase brain access for the luciferase substrate, a synthetic D-luciferin analog (Cycluc1 [30]). For each recording, mice were anesthetized and intraperitoneally (i.p.) injected with cycluc1 (100 ul at 5 mM), 5 min before imaging. AST-004 or vehicle were then administered 12.5 min after the initial Cycluc1 injection. Bioluminescent signals from the brain were collected during 40 min continuous recordings as total flux (photons per second) and plotted as emission curves using Living Imaging Software 4.0. Finally, the total photon flux levels were compared 30 min after AST-004 or vehicle were injected.

Statistics

For statistical analysis, GraphPad/Prism was used. Data were checked for normal distribution by Q–Q plot analysis and the Shapiro–Wilk normality test. Unpaired, two-tailed, Student’s t-test was used for bioluminescent photon flux analysis. One-way ANOVA test was used for the rest of the analyses. Bonferroni correction was utilized for post hoc comparisons for determining significant differences between different groups of samples, once ANOVA revealed a significant difference.

Results

AST-004 Reduces TBI-induced Cell Death and Blood Brain Barrier Disruption

Mice received a single TBI and were treated with either vehicle or AST-004 (intraperitoneal (IP) injection; 0.22 mg/kg) 30 min after insult. Disruption of the BBB was assayed 72 h post-TBI, using the Evans blue (EB) extravasation assay (Fig. 1). EB was injected 2 h prior to imaging, and the brains were removed and positioned in the Xenogen IVIS imaging system. Significantly higher EB staining was observed in the cortex of animals subjected to TBI only (1.83 ± 0.16 Ipsi/Cntr, n = 5, p < 0.001), compared to sham (1.10 ± 0.03 Ipsi/Cntr, n = 5) and TBI + AST-004 treatment (1.47 ± 0.12 Ipsi/Cntr, n = 6, p < 0.025). The difference between sham and AST-004-treated animals was not statistically significant (Fig. 2a, c).

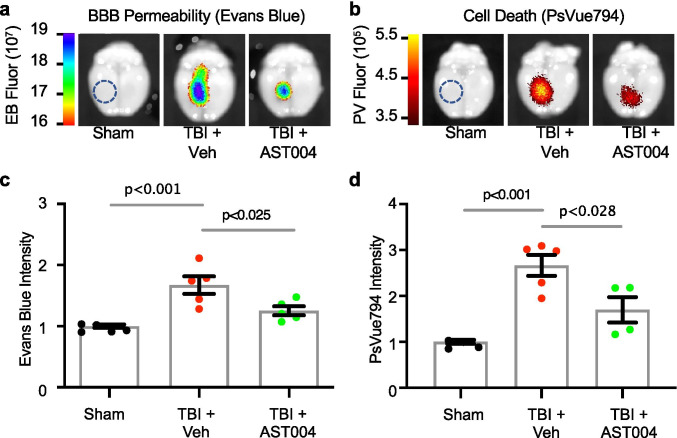

Fig. 2.

TBI-induced increases in BBB permeability (Evans blue) and cell death (PSVue794) were reduced by AST-004 treatment. a, b Images of Evans blue or PSVue794-injected mice brains 3 days post-TBI, collected on the Xenogen IVIS system. Epi-fluorescence radiance units are the number of photons per second leaving a square centimeter of brain tissue radiating into a solid angle of one steradian (photons/s/cm2/sr). c, d Histogram plots of Evans blue and PSVue794 fluorescence intensity (arbitrary units) normalized to sham. Size of ROIs indicated with blue dashed circles in sham image panels. Each filled circle in the histogram bars represents a single mouse. Total number of mice used for sham: 9 males, for TBI + vehicle: 10 males, for TBI + AST-004: 9 males

TBI-induced cell death was also assessed ex vivo using the dye PSVue794. Near-infrared (NIR) imaging was performed with the IVIS system in the same cohorts. CCCI-triggered cell death was mainly located around the site of impact and significantly higher (2.68 ± 0.22, n = 5, p < 0.001) than sham (mean normalized to 1, n = 4). This relatively focal injury was significantly reduced by AST-004 administration (1.71 ± 0.29, n = 4, p < 0.028) (Fig. 2b, d). Note the cell death profile spatially overlaps with the BBB disruption.

AST-004 Treatment Reduces mRNA Levels of Both GFAP and Iba1 in Mice Subjected to TBI

We assayed levels of mRNA for the astrogliosis biomarker, GFAP, and the microgliosis biomarker, Iba1, in shams and TBI mice treated with vehicle only or AST-004. mRNA was extracted from brain homogenates 6 days post-injury (Fig. 1). We observed a significant increase in GFAP expression in the ipsilateral cortex of mice subjected to TBI (8.42 ± 1.07, n = 7, p < 0.0001) relative to sham (1.00 ± 0.14, n = 6), which was reduced in mice treated with AST-004 (2.24 ± 0.25, n = 6, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 3a). We observed a similar increase in expression of Iba1 after TBI (2.36 ± 0.33, n = 6, p < 0.01), compared to shams (1.26 ± 0.09, n = 5), and AST-004 treatment significantly lowered Iba1 expression (1.77 ± 0.14, n = 5, p < 0.05) (Fig. 3b). Control mRNA levels for GFAP in the ipsilateral cerebellum and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) in the ipsilateral cortex exhibited no significant differences (Fig. 3c, d).

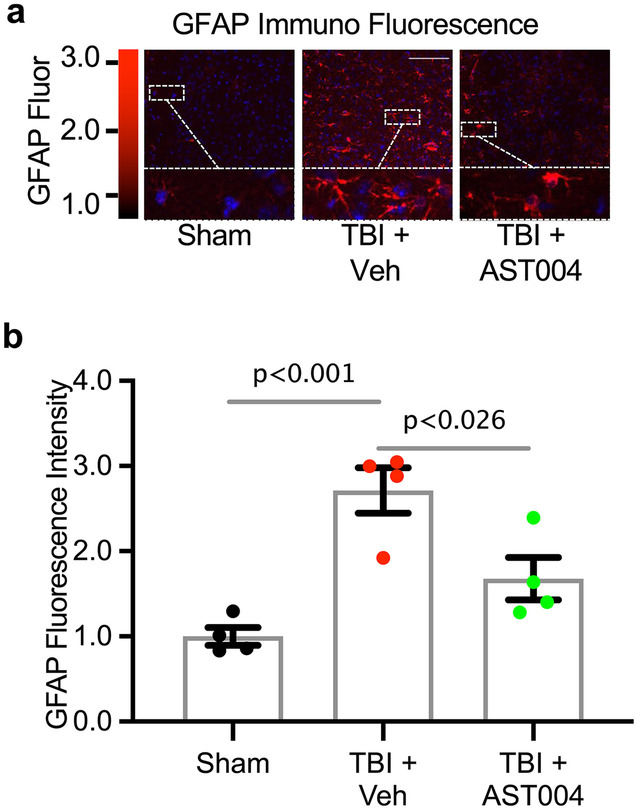

AST-004 Treatment Reduces Expression of GFAP Protein

In separate cohorts of mice, we investigated the effect of AST-004 treatment on GFAP-protein levels after TBI. Brains were collected and prepared for GFAP immunocytochemistry 3 days post-injury (Fig. 1). Consistent with our qRT-PCR analysis, GFAP levels were significantly increased by TBI (2.24 ± 0.19, n = 4, p < 0.001) compared to sham (1.06 ± 0.05, n = 4), and AST-004 reduced levels of GFAP immunolabeling in the ipsilateral cortex (1.48 ± 0.25, n = 5, p < 0.03 (Fig. 4a, b).

Fig. 4.

TBI-induced increases in GFAP immunofluorescence are reduced by AST-004 treatments 3 days post-injury. a Image panels of brain sections immunolabeled for GFAP. Mice underwent sham or TBI and received AST-004 treatment (0.22 mg/kg) or only vehicle 30 min post-injury. Scale bar 100 µm. b Histogram plot of mean fluorescence intensity (arbitrary units) normalized to sham. Each filled circle in the histogram bars represents a single mouse. Total number of mice used for sham: 4 males, for TBI + vehicle: 4 males, for TBI + AST-004: 4 males

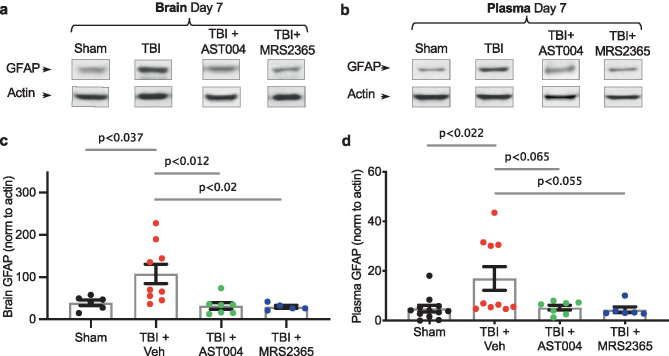

We also measured GFAP-expression levels 7 days post-injury in both brain homogenates and plasma using Western blot analysis (Fig. 1). Injured mice were treated with either vehicle, AST-004 or with MRS2365. The latter, as noted above, serves as a prodrug for AST-004. We observed significantly higher levels of GFAP in both the brain (107.6 ± 23.1, n = 9, p < 0.037) (Fig. 5a, b) and plasma (17.0 ± 4.7, n = 10, p < 0.022) (Fig. 5c, d) samples of TBI mice treated with only vehicle compared to sham brains (39.3 ± 6.5, n = 6) or plasma (4.8 ± 1.4, n = 12), respectively. GFAP immunolabeling was also reduced in mice treated with either AST-004 in brain (31.8 ± 8.0, n = 7, p < 0.012) and plasma (5.3 ± 1.0, n = 7, p < 0.065) or in mice treated with MRS2365 in brain (29.4 ± 3.6, n = 5, p < 0.02) and plasma (4.4 ± 1.2, n = 6, p < 0.055) samples, respectively.

Fig. 5.

TBI-induced increases in GFAP expression in the brain and plasma are reduced by AST-004 and MRS2365 treatments 7 days post-injury. Representative Western blots are shown for brain homogenates a and plasma b collected 7 days post-TBI. c, d Histogram plots of GFAP expression levels normalized by actin as labeled. Injured mice or shams were injected with either vehicle, AST-004 (0.22 mg/kg) or MRS2365 (0.22 mg/kg) 30 min after TBI. Each filled circle in the histogram bars represents a single mouse. Total number of mice used for sham: 12 males, for TBI + vehicle: 9 males, for TBI + AST-004: 7 males and for TBI + MRS2365: 6 males

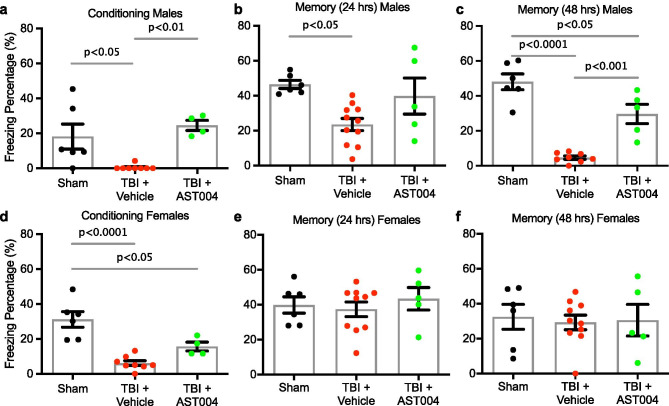

AST-004 Treatments Reduce TBI-induced Impairment in Spatial Memory

To assess the behavioral impact of acute AST-004 treatments on long-term memory function, we tested mice (sham, TBI + vehicle and TBI + AST-004) 4 weeks post-injury with contextual fear conditioning (Fig. 1). We observed decreased freezing behavior after shock immediately after training in both male (0.5 ± 0.5, n = 8, p < 0.05) and female (6.1 ± 1.4, n = 8, p < 0.0001) mice subjected to TBIs, compared to sham males (18.2 ± 7.2, n = 6) and sham females (31.2 ± 4.5, n = 6). AST-004 treatment reversed this phenotype in males (19.6 ± 5.4, n = 4, p < 0.01) and reduced significant loss of freezing behavior in females (15.6 ± 2.5, n = 4, p < 0.05) (Fig. 6a, d). Loss of freezing behavior was observed in male mice at 24 h (23.5 ± 3.5, n = 11, p < 0.01) and 48 h (4.7 ± 1.0, n = 8, p < 0.0001), compared to sham males (46.4 ± 2.3, n = 6; 48.0 ± 4.5, n = 6, respectively) (cf. Figure 6b, c; e, f). Freezing behavior was significantly increased in male mice treated with AST-004 at 48 h (29.7 ± 5.5, n = 8, p < 0.001), but was not significantly increased at 24 h (39.8 + 10.3, n = 5, ns). For female mice subjected to TBIs, spatial memory was not reduced at either 24 h (37.4 ± 4.2, n = 10, ns) or 48 h (29.3 ± 4.2, n = 10, ns) compared to sham controls. Values were also not significantly different in AST-004-treated females at 24 h (43.4 + 6.5, n = 5, ns) or at 48 h (30.6 + 9.0, n = 5, ns) (Fig. 6b, c).

Fig. 6.

AST-004 treatments improve spatial memory 30 days post-injury. TBI-injured mice or shams were injected with either vehicle or AST-004 (0.22 mg/kg) 30 min after injury. Contextual fear conditioning tests were performed 30 days later. All panels show freezing percentages during contextual fear memory training and testing (24 h and 48 h after TBI). Males (a–c) and females (d–f) were analyzed separately. Note that AST-004 reversed TBI-induced impairment in freezing behavior after shock (training session) in both sexes. However, TBI-induced long-memory loss was only observed in male mice, which was significantly improved by AST-004 treatment. Each filled circle in the histogram bars represents a single mouse. Number of mice used for sham: 6 males and 6 females, for TBI + vehicle: 11 males and 10 females, for TBI + AST-004: 5 males and 5 females

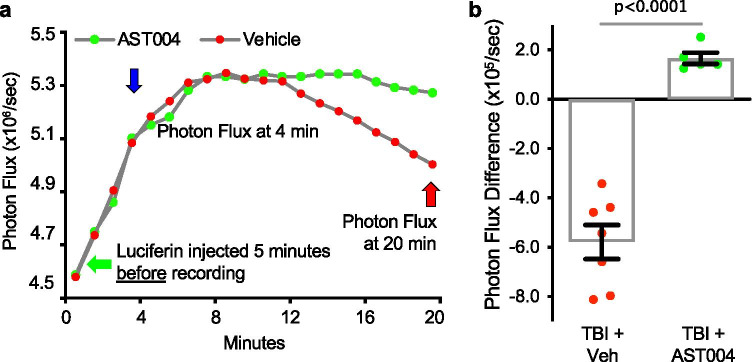

In Vivo Bioluminescent Imaging Indicates A3R Agonist AST-004 Increases ATP in Astrocytes

Our working model of astrocyte-enhanced neuroprotection is that AST-004 binds to A3Rs, stimulating IP3-mediated Ca2+ release from intracellular stores. Mitochondria, in turn, sequester some of this Ca2+, which acts as a cofactor to increase enzymatic activity in the citric acid cycle, ultimately leading to increased capacity for ATP production [31]. To test this model in vivo, transgenic mice expressing the Luciferase-reporter gene in astrocytes were subjected to CCCI-TBI. Two to 6 days after the initial trauma, mice were injected IP with a synthetic D-luciferin analog (Cycluc 1) and bioluminescent signals recorded using the Xenogen IVIS (Fig. 1). Mice injected with AST-004 4 min after the recordings began exhibited significantly higher photon flux levels (1.66 × 105/s ± 0.22, n = 5, p < 0.0001) compared to mice injected with vehicle (−5.79 ± 0.69, n = 7) at 20 min (Fig. 7a, b). These data are consistent with our hypothesis that AST-004 stimulates greater ATP production in astrocytes.

Fig. 7.

In vivo bioluminescent imaging indicates AST-004 increases ATP in astrocytes. a Photon flux plots of TBI-injured transgenic mice expressing the Luciferase-reporter gene in astrocytes (GFAP promoter, Jackson Labs) after intraperitoneal injections (IP) of synthetic D-luciferin analog Cycluc1 (5 mM, 100 µl). Bioluminescent signals were recorded with a Xenogen IVIS Spectrum Imager, beginning 5 min after Cycluc1 injection (green arrow). Mice were then injected IP with either vehicle or AST-004 at 4 min (blue arrow); the photon flux was measured at the time of injection and then compared to the photon flux level at 20 min (red arrow). Every 24 h after the initial flux recordings, the same mice were injected again for another photon flux recording, alternating the identity of the test injection between vehicle and AST-004. b Histogram plot showing photon flux differences at 20 min compared to corresponding levels at 4 min. Note mice injected with AST-004 exhibited positive photon flux difference compared to a loss of photon flux (negative) in vehicle-treated mice, consistent with higher ATP production in astrocytes of AST-004-treated mice. Number of mice used for TBI + vehicle: 2 females, for TBI + AST-004: 2 females. In total, 12 measurements were used from these mice every 24 h. alternating between vehicle and AST-004

Discussion

In our previous work, neither 2MeSADP nor MRS2365 agonist could be detected in blood samples as early as 1 min post-dosing utilizing liquid chromatography mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS). The half-lives of 2MeSADP and MRS2365 were estimated to be less than 10 s in mouse blood, whereas their nucleoside metabolites exhibited half-lives of ~20 min [24], thus suggesting the hypothesis tested here that synthesized AST-004 [25] was the active neuroprotective molecule.

Cell death and loss of BBB integrity are commonly used biomarkers for the severity of injury post-TBI [32–34]. We observed significant increases for both of these measures in previous work [19, 35]. More importantly, acute treatment with AST-004 significantly reduced both biomarkers. We also found significant increases in mRNA levels for GFAP (astrogliosis) and Iba1 (microgliosis) in the ipsilateral hemispheres. Subsequent experiments quantifying protein levels for GFAP confirmed these results. Here again, AST-004 treatments effectively reduced mRNA and protein levels of GFAP, although increased levels of cortical Iba1 mRNA were not completely blocked. We note that TBI-induced inflammation can have beneficial effects post-injury, such as the removal of cellular debris. Consequently, an ideal treatment may need to preserve a limited, beneficial, inflammation response [6, 36]. Consistent with this notion, nearly complete obliteration of microglia in distinct animal models of brain injury increased neuronal damage and worsened injury outcome [6, 36–38]. Irrespective of the underlying mechanism, AST-004 treatment significantly decreases TBI-induced damage and is neuroprotective.

In the long term (30 days post-injury), we observed decreased levels of freezing behavior during training sessions of contextual fear conditioning for both sexes, an effect prevented by AST-004 treatment of male mice, and which trended less in treated female mice. Interestingly, loss of memory 24 and 48 h post-training was not observed in female mice. Possibly, the female estrous cycle phase provided additional protection against long-term memory loss after TBI, as variation during the phases of the estrous cycle are known to affect fear conditioning responses in female rodents [39–41]. Estrogen and progesterone are both neuroprotective after a traumatic brain injury [42] and estrogen facilitates contextual fear conditioning learning [43]. Irrespective of the potential beneficial effects of these sex hormones, AST-004 treatment effectively rescued long-term memory of TBI males. In the clinic, this may translate to an effective treatment for a TBI-induced increase in cognitive impairment [44] and risk-taking behavior [45, 46], of which both have been observed in animal models [37, 47].

Recent studies by our group showed the KI of AST-004 to be 5 × lower for A3Rs compared to A1Rs [24]. There was no significant binding to either A2a or A2b receptors in a commercial target selectivity panel screen (Cerep Bioprint) revealing no additional receptor or enzyme targets for AST-004 [24]. We thus conclude that neuroprotection by AST-004 is largely mediated by stimulation of A3Rs. Indeed, A3R agonists have been recognized as potential neuroprotectants since the mid-1990s [48]. However, conflicting results have been reported depending on whether acute or chronic doses of A3R agonists were administered prior to ischemia [49–52]. A recent study from Farr et al. on TBI was also consistent with anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective effects of acute A3R stimulation [53]. Higher affinity agonists such as Cl-IB-MECA [54, 55] are known to rapidly desensitize A3Rs, thus blocking protective downstream signaling. Likewise, our group has also shown that unlike AST-004, high-affinity A3R agonists such as NECA, Cl-IB-MECA, and MRS5698 potently activate β-arrestin activity, a prime mediator of receptor desensitization [24]. Our estimates of receptor occupancy for AST-004 at mouse-TBI efficacious doses appear less than 5% [24], consistent with a high A3R reserve in the mouse brain. It is likely that previous studies with prototypical A3R agonists resulted in much higher receptor occupancy and receptor desensitization.

Concentrations of adenosine in the brain under basal conditions have been measured in the range of 10–200 nM [56, 57]. With an adenosine affinity of 1–6.5 μM [58], it is likely that A3Rs are “silent” under normal physiological conditions. After a brain trauma, endogenous adenosine concentrations can reach levels greater than 10 μM in the cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) of rats within 20 min of TBI, then return to baseline by 40 min [59]. Elevated-CSF adenosine concentrations have also been observed in humans who suffered severe TBI [60]. Given their low adenosine affinity, A3Rs are expected to be activated only under these pathophysiological situations, or when exogenous agonists are added. Of note, knockout mice null for A3Rs exhibit increased neurodegeneration in response to mild hypoxia [61] and show significantly larger cerebral infarct sizes in response to middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) [61, 62]. These data suggest that normally “silent” A3Rs are reserved for neuroprotection when needed.

Our previous work indicated that the neuroprotective efficacy of MRS2365 and 2MeSADP was mediated by the type-2 isoform of IP3Rs [18, 63], which is principally expressed in astrocytes [64, 65] and critical to their mitochondrial metabolism [20]. We cannot rule out contributions of A3R agonism on microglia to neuroprotection, as this cell type expresses A3Rs in the brain. Also, A3R agonists can act as inhibitors of proinflammatory cytokines [66–68], and A3Rs are highly expressed in peripheral inflammatory cells and in blood mononuclear cells of patients with autoimmune inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, and Crohn's disease [69]. Our group also recently reported similar neuroprotective action of compounds that increase the opening of the KCNQ (Kv7, “M-type”) K+ channels in neurons that play a dominant role in the regulation of excitability, which fits in with the need to conserve metabolic stores [70, 71]. Like the results reported here, application of retigabine [72–75], after moderate TBI, reduced most of the inflammatory responses in the brain, as well as preventing post-traumatic seizures [35]. It may turn out that a combination of drugs acting on both astrocytes and neurons prove to be most efficacious in preventing TBI-induced brain dysfunction.

Finally, A3Rs are GPCRs that canonically activate the Gi/o subtypes of G proteins and inhibit adenylyl cyclase activity, as well as regulate neuronal K+ and Ca2+ ion channels [76]. However, A3Rs also appear to effectively couple to Gq/11 [77]. Given the dependence of our neuroprotective efficacy on expression of type 2 IP3Rs, our data are consistent with an important role of Gq/11. We postulate that IP3-mediated Ca2+ release leads to increased metabolism via stimulation of Ca2+ sensitive mitochondrial enzymes, including Ca2+-activated dehydrogenases and the Ca2+-activated pyruvate dehydrogenase phosphatase [18, 20, 63]. This mechanism of action predicts higher mitochondrial membrane potentials, as we previously reported [63], and increased ATP levels in astrocytes, as our current data indicate.

Conclusions

Our data indicate that AST-004 is an active neuroprotective molecule that reduces tissue damage and loss of function after brain injury. It is likely that previously reported neuroprotective effects observed with P2Y1R agonists [18–20] were also due to their adenosine-like metabolites, given their rapid metabolism [24]. Interestingly, we demonstrated P2Y1R agonists were efficacious even when treatment was delayed 3 h or 24 h post-injury [18, 20]. Consequently, it is likely that delayed treatments with AST-004, beyond the 30 min tested here, will be efficacious for at least 24 h. Taken together, these data indicate AST-004 will be a promising new therapeutic for both the acute and long-term consequences of brain injuries.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Images were generated in the Core Optical Imaging Facility which is supported by UT Health San Antonio and National Institutes of Health — National Cancer Institute P30 CA54174.

Required Author Forms

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the online version of this article.

Abbreviations

- 2MeS-ADP

2-Methylthio-adenosine-5′-diphosphate

- A1Rs

Adenosine A1 receptor

- A2aR

Adenosine A2a receptor

- A2bR

Adenosine A2b receptor

- A3R

Adenosine A3 receptor

- ANOVA

Analysis of variance

- AR

Adenosine receptor

- AST-004

(1R,2R,3S,4R,5S)-4-(6-amino-2- (methylthio)-9H-purin-9-yl)-1-(hydroxymethyl)bicyclo [3.1.0] hexane-2,3-diol

- ATP

Adenosine 5′-triphosphate

- BBB

Blood brain barrier

- Ca2+

Calcium ion

- CCCI

Control closed cortical impact

- Cl-IB-MECA

2-Cl N6-(3-chloro or iodobenzyl)-adenosine-5′-N-methylcarboxamide

- cm

Centimeter

- Cntr

Contralateral

- CSF

Cerebral spinal fluid

- EB

Evans blue

- ER

Endoplasmic reticulum

- FC

Fear conditioning

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- GAPDH

Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- GFAP

Glial fibrillary acidic protein

- GPCR

G-protein coupled receptor

- Gq/11

GTP-binding protein subtype q/11 family

- HPRT

Hypoxanthine–guanine phosphoribosyltransferase

- Iba1

Ionized Ca2+-binding adaptor molecule 1

- IHC

Immunohistochemistry

- IP3

Inositol (1,4,5) tri-phosphate

- Ipsi

Ipsilateral

- IVIS

In vivo imaging system

- K+

Potassium channels

- KCNQ

Potassium channel, voltage-gated, KQT-like subfamily

- kg

Kilograms

- KI

Inhibition constant

- Kv7

M-type KCNQ potassium channel

- LC

Liquid chromatography

- mA

Milliamp

- MCAO

Middle cerebral artery occlusion

- mg

Milligrams

- mM

Millimolar

- MRS2365

(N)-methanocarba-2MeSADP

- MRS5698

Molecular Recognition Section compound 5698

- MS

Mass spectrometry

- NA

Numerical aperture

- NECA

5′-N-ethylcarboxamide adenosine

- NFL

National Football League

- NIH

National Institutes of Health

- NIR

Near-infrared

- nM

Nanomolar

- P2Y1R

P2Y type 1 receptor

- PBS

Phosphate-buffered saline

- PFA

Paraformaldehyde

- qRT-PCR

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

- RNA

Ribonucleic acid

- ROI

Region of interest

- RT

Room temperature

- S.E.M.

Standard error of the mean

- TBI

Traumatic brain injury

- TC

Threshold cycle

Author Contribution

EB, FV, TL, WK, and JDL formulated the hypotheses, organized, and designed the studies. EB, FV, SC, LP, VB, SK, DH, AS, CT, DL, and SS performed experiments and analyzed the data. TL, WK, and JDL contributed reagents and supplies necessary for the study. EB, FV, TL, MSS, and JDL wrote and edited the paper and figures.

Funding

These studies were supported by grants from the Department of Defense: W81XWH-15–1-0283 (J. Lechleiter) and W81XWH-15–1-0284 (M. Shapiro) and from the Welch Foundation Grant: AQ-1980–20190330 (R. Brenner).

Availability of Data and Materials

All data and materials used in this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Animal care and experimental procedures performed in this study were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at UT Health San Antonio, in compliance with the Public Law 89–544 (Animal Welfare Act) and its amendments and Public Health Services Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (PHS Policy) using the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (Guide) as the basis of operation. UT Health San Antonio is accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care, International (AAALAC).

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Lechleiter co-founded Astrocyte Pharmaceuticals and is currently a scientific advisor. Dr. Liston is Vice President of Research at Astrocyte Pharmaceuticals. Astrocyte Pharmaceuticals is a privately held pharmaceutical company that has the exclusive use of patent rights for AST-004 for developing and commercializing its use to treat brain injuries such as TBI and concussions.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Eda Bozdemir and FabioA. Vigil are co-first authors.

Contributor Information

Eda Bozdemir, Email: edabozdemir@gmail.com.

Fabio A. Vigil, Email: BorgesVigil@uthscsa.edu

Sang H. Chun, Chun@livemail.uthscsa.edu

Liliana Espinoza, EspinozaL3@livemail.uthscsa.edu.

Vladislav Bugay, Email: bugay@uthscsa.edu.

Sarah M. Khoury, KhouryS@livemail.uthscsa.edu

Deborah M. Holstein, Email: HolsteinD@uthscsa.edu

Aiola Stoja, stoja@livemail.uthscsa.edu.

Damian Lozano, Email: lozanod5@uthscsa.edu.

Ceyda Tunca, Email: tunca.ceyda2000@gmail.com.

Shane M. Sprague, Email: SPRAGUES@uthscsa.edu

Jose E. Cavazos, Email: CAVAZOSJ@uthscsa.edu

Robert Brenner, Email: brennerr@uthscsa.edu.

Theodore E. Liston, Email: liston@astrocytepharma.com

Mark S. Shapiro, Email: SHAPIROM@uthscsa.edu

James D. Lechleiter, Email: lechleiter@uthscsa.edu

References

- 1.CDC. TBI: Get the Facts | Concussion | Traumatic Brain Injury | CDC Injury Center. 2019; https://www.cdc.gov/traumaticbraininjury/get_the_facts.html.

- 2.Valera EM, Cao A, Pasternak O, Shenton ME, Kubicki M, Makris N, et al. White Matter Correlates of Mild Traumatic Brain Injuries in Women Subjected to Intimate-Partner Violence: A Preliminary Study. J Neurotrauma. 2019;36(5):661–668. doi: 10.1089/neu.2018.5734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tanielian TL, Jaycox L. Invisible wounds of war: psychological and cognitive injuries, their consequences, and services to assist recovery. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coronado VG, Haileyesus T, Cheng TA, Bell JM, Haarbauer-Krupa J, Lionbarger MR, et al. Trends in Sports- and Recreation-Related Traumatic Brain Injuries Treated in US Emergency Departments: The National Electronic Injury Surveillance System-All Injury Program (NEISS-AIP) 2001–2012. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2015;30(3):185–197. doi: 10.1097/HTR.0000000000000156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.CDC, NIH, DoD, Panel VL. Report to Congress on Traumatic Brain Injury in the United States: Understanding the Public Health Problem among Current and Former Military Personnel. 2013.

- 6.Corps KN, Roth TL, McGavern DB. Inflammation and neuroprotection in traumatic brain injury. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72(3):355–362. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.3558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bugay V, Bozdemir E, Vigil FA, Chun SH, Holstein DM, Elliott WR, et al. A Mouse Model of Repetitive Blast Traumatic Brain Injury Reveals Post-Trauma Seizures and Increased Neuronal Excitability. J Neurotrauma. 2020;37(2):248–261. doi: 10.1089/neu.2018.6333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gruenbaum SE, Zlotnik A, Gruenbaum BF, Hersey D, Bilotta F. Pharmacologic Neuroprotection for Functional Outcomes After Traumatic Brain Injury: A Systematic Review of the Clinical Literature. CNS Drugs. 2016;30(9):791–806. doi: 10.1007/s40263-016-0355-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shi J, Dong B, Mao Y, Guan W, Cao J, Zhu R, et al. Review: Traumatic brain injury and hyperglycemia, a potentially modifiable risk factor. Oncotarget. 2016;7(43):71052–71061. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.11958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ziebell JM, Morganti-Kossmann MC. Involvement of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in the pathophysiology of traumatic brain injury. Neurotherapeutics. 2010;7(1):22–30. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2009.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sizemore G, Lucke-Wold B, Rosen C, Simpkins JW, Bhatia S, Sun D. Temporal Lobe Epilepsy, Stroke, and Traumatic Brain Injury: Mechanisms of Hyperpolarized, Depolarized, and Flow-Through Ion Channels Utilized as Tri-Coordinate Biomarkers of Electrophysiologic Dysfunction. OBM Neurobiol. 2018;2(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Hiebert JB, Shen Q, Thimmesch AR, Pierce JD. Traumatic brain injury and mitochondrial dysfunction. Am J Med Sci. 2015;350(2):132–138. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0000000000000506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rasband MN. Glial Contributions to Neural Function and Disease. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2016;15(2):355–361. doi: 10.1074/mcp.R115.053744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sofroniew MV. Molecular dissection of reactive astrogliosis and glial scar formation. Trends Neurosci. 2009;32(12):638–647. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burda JE, Bernstein AM, Sofroniew MV. Astrocyte roles in traumatic brain injury. Exp Neurol. 2016;275(Pt 3):305–315. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2015.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Donat CK, Scott G, Gentleman SM, Sastre M. Microglial Activation in Traumatic Brain Injury. Front Aging Neurosci. 2017;9:208. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2017.00208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kohno Y, Ji X, Mawhorter SD, Koshiba M, Jacobson KA. Activation of A3 adenosine receptors on human eosinophils elevates intracellular calcium. Blood. 1996;88(9):3569–3574. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zheng W, Talley Watts L, Holstein DM, Wewer J, Lechleiter JD. P2Y1R-initiated, IP3R-dependent stimulation of astrocyte mitochondrial metabolism reduces and partially reverses ischemic neuronal damage in mouse. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2013;33(4):600–611. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2012.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Talley Watts L, Sprague S, Zheng W, Garling RJ, Jimenez D, Digicaylioglu M, et al. Purinergic 2Y(1) receptor stimulation decreases cerebral edema and reactive gliosis in a traumatic brain injury model. J Neurotrauma. 2013;30(1):55–66. doi: 10.1089/neu.2012.2488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zheng W, Watts LT, Holstein DM, Prajapati SI, Keller C, Grass EH, et al. Purinergic receptor stimulation reduces cytotoxic edema and brain infarcts in mouse induced by photothrombosis by energizing glial mitochondria. PLoS One. 2010;5(12):e14401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Yuan S, Chan HC, Vogel H, Filipek S, Stevens RC, Palczewski K. The Molecular Mechanism of P2Y1 Receptor Activation. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2016;55(35):10331–10335. doi: 10.1002/anie.201605147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wootten D, Christopoulos A, Sexton PM. Emerging paradigms in GPCR allostery: implications for drug discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2013;12(8):630–644. doi: 10.1038/nrd4052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gessi S, Varani K, Merighi S, Morelli A, Ferrari D, Leung E, et al. Pharmacological and biochemical characterization of A3 adenosine receptors in Jurkat T cells. Br J Pharmacol. 2001;134(1):116–126. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liston TE, Hinz S, Muller C, Holstein D, Wendling J, Melton RJ, et al. Nucleotide P2Y1 Receptor Agonists are In Vitro and In Vivo Prodrugs of A1/A3 Adenosine Receptor Agonists: Implications for Roles of P2Y1 and A1/A3 Adenosine Receptors in Health and Disease. Purinergic Signal. 2020;in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Ravi RG, Kim HS, Servos J, Zimmermann H, Lee K, Maddileti S, et al. Adenine nucleotide analogues locked in a Northern methanocarba conformation: enhanced stability and potency as P2Y(1) receptor agonists. J Med Chem. 2002;45(10):2090–2100. doi: 10.1021/jm010538v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Osier N, Dixon CE. The Controlled Cortical Impact Model of Experimental Brain Trauma: Overview, Research Applications, and Protocol. Methods Mol Biol. 2016;1462:177–192. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-3816-2_11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim WB, Cho JH. Synaptic Targeting of Double-Projecting Ventral CA1 Hippocampal Neurons to the Medial Prefrontal Cortex and Basal Amygdala. J Neurosci. 2017;37(19):4868–4882. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3579-16.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tovote P, Fadok JP, Luthi A. Neuronal circuits for fear and anxiety. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2015;16(6):317–331. doi: 10.1038/nrn3945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu C, Krabbe S, Grundemann J, Botta P, Fadok JP, Osakada F, et al. Distinct Hippocampal Pathways Mediate Dissociable Roles of Context in Memory Retrieval. Cell. 2016;167(4):961–72 e16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Evans MS, Chaurette JP, Adams ST, Jr, Reddy GR, Paley MA, Aronin N, et al. A synthetic luciferin improves bioluminescence imaging in live mice. Nature methods. 2014;11(4):393–395. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parpura V, Fisher ES, Lechleiter JD, Schousboe A, Waagepetersen HS, Brunet S, et al. Glutamate and ATP at the Interface Between Signaling and Metabolism in Astroglia: Examples from Pathology. Neurochem Res. 2017;42(1):19–34. doi: 10.1007/s11064-016-1848-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang X, Chen Y, Jenkins LW, Kochanek PM, Clark RS. Bench-to-bedside review: Apoptosis/programmed cell death triggered by traumatic brain injury. Crit Care. 2005;9(1):66–75. doi: 10.1186/cc2950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bayly PV, Dikranian KT, Black EE, Young C, Qin YQ, Labruyere J, et al. Spatiotemporal evolution of apoptotic neurodegeneration following traumatic injury to the developing rat brain. Brain Res. 2006;1107(1):70–81. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.05.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chodobski A, Zink BJ, Szmydynger-Chodobska J. Blood-brain barrier pathophysiology in traumatic brain injury. Transl Stroke Res. 2011;2(4):492–516. doi: 10.1007/s12975-011-0125-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vigil FA, Bozdemir E, Bugay V, Chun SH, Hobbs M, Sanchez I, et al. Prevention of brain damage after traumatic brain injury by pharmacological enhancement of KCNQ (Kv7, “M-type” ) K(+) currents in neurons. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2020;40(6):1256–1273. doi: 10.1177/0271678X19857818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Almeida-Correa S, Amaral OB. Memory labilization in reconsolidation and extinction–evidence for a common plasticity system? J Physiol Paris. 2014;108(4–6):292–306. doi: 10.1016/j.jphysparis.2014.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ekmark-Lewen S, Lewen A, Meyerson BJ, Hillered L. The multivariate concentric square field test reveals behavioral profiles of risk taking, exploration, and cognitive impairment in mice subjected to traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2010;27(9):1643–1655. doi: 10.1089/neu.2009.0953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bennett RE, Brody DL. Acute reduction of microglia does not alter axonal injury in a mouse model of repetitive concussive traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2014;31(19):1647–1663. doi: 10.1089/neu.2013.3320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rey CD, Lipps J, Shansky RM. Dopamine D1 receptor activation rescues extinction impairments in low-estrogen female rats and induces cortical layer-specific activation changes in prefrontal-amygdala circuits. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014;39(5):1282–1289. doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Milad MR, Igoe SA, Lebron-Milad K, Novales JE. Estrous cycle phase and gonadal hormones influence conditioned fear extinction. Neuroscience. 2009;164(3):887–895. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Graham BM, Daher M. Estradiol and Progesterone have Opposing Roles in the Regulation of Fear Extinction in Female Rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2016;41(3):774–780. doi: 10.1038/npp.2015.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brotfain E, Gruenbaum SE, Boyko M, Kutz R, Zlotnik A, Klein M. Neuroprotection by Estrogen and Progesterone in Traumatic Brain Injury and Spinal Cord Injury. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2016;14(6):641–653. doi: 10.2174/1570159X14666160309123554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Matsumoto YK, Kasai M, Tomihara K. The enhancement effect of estradiol on contextual fear conditioning in female mice. PLoS One. 2018;13(5):e0197441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Arciniegas DB, Held K, Wagner P. Cognitive Impairment Following Traumatic Brain Injury. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2002;4(1):43–57. doi: 10.1007/s11940-002-0004-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kennedy E, Cohen M, Munafo M. Childhood Traumatic Brain Injury and the Associations With Risk Behavior in Adolescence and Young Adulthood: A Systematic Review. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2017;32(6):425–432. doi: 10.1097/HTR.0000000000000289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.James LM, Strom TQ, Leskela J. Risk-taking behaviors and impulsivity among veterans with and without PTSD and mild TBI. Mil Med. 2014;179(4):357–363. doi: 10.7205/MILMED-D-13-00241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ozga-Hess JE, Whirtley C, O'Hearn C, Pechacek K, Vonder Haar C. Unilateral parietal brain injury increases risk-taking on a rat gambling task. Exp Neurol. 2020;327:113217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Rudolphi KA, Schubert P. Adenosine and brain ischemia. In: Belardinell L, Pelleg A, editors. Adenosine and ademime nucleotides: from molecular biology to integrative physiology: Kluwer Norwell; 1995. p. 391–6.

- 49.von Lubitz DK, Lin RC, Popik P, Carter MF, Jacobson KA. Adenosine A3 receptor stimulation and cerebral ischemia. Eur J Pharmacol. 1994;263:59–67. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(94)90523-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.von Lubitz DK, Lin RC, Boyd M, Bischofberger N, Jacobson KA. Chronic administration of adenosine A3 receptor agonist and cerebral ischemia: neuronal and glial effects. Eur J Pharmacol. 1999;367(2–3):157–163. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00977-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.von Lubitz DK. Adenosine in the treatment of stroke: yes, maybe, or absolutely not? Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2001;10(4):619–632. doi: 10.1517/13543784.10.4.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Choi IY, Lee JC, Ju C, Hwang S, Cho GS, Lee HW, et al. A3 adenosine receptor agonist reduces brain ischemic injury and inhibits inflammatory cell migration in rats. Am J Pathol. 2011;179(4):2042–2052. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Farr SA, Cuzzocrea S, Esposito E, Campolo M, Niehoff ML, Doyle TM, et al. Adenosine A3 receptor as a novel therapeutic target to reduce secondary events and improve neurocognitive functions following traumatic brain injury. J Neuroinflammation. 2020;17(1):339. doi: 10.1186/s12974-020-02009-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Klaasse EC, Ijzerman AP, de Grip WJ, Beukers MW. Internalization and desensitization of adenosine receptors. Purinergic Signal. 2008;4(1):21–37. doi: 10.1007/s11302-007-9086-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Trincavelli ML, Ciampi O, Martini C. The Desensitization as A3 Adenosine Receptor Regulation: Physiopathological Implications. In: Borea PA, editor. A3 Adenosine Receptors from Cell Biology to Pharmacology and Therapeutics. p. 75–90.

- 56.Phillis JW. Adenosine in the control of the cerebral circulation. Cerebrovasc Brain Metab Rev. 1989;1(1):26–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ballarin M, Fredholm BB, Ambrosio S, Mahy N. Extracellular levels of adenosine and its metabolites in the striatum of awake rats: inhibition of uptake and metabolism. Acta Physiol Scand. 1991;142(1):97–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1991.tb09133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yan L, Burbiel JC, Maass A, Muller CE. Adenosine receptor agonists: from basic medicinal chemistry to clinical development. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2003;8(2):537–576. doi: 10.1517/14728214.8.2.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bell MJ, Kochanek PM, Carcillo JA, Mi Z, Schiding JK, Wisniewski SR, et al. Interstitial adenosine, inosine, and hypoxanthine are increased after experimental traumatic brain injury in the rat. J Neurotrauma. 1998;15(3):163–170. doi: 10.1089/neu.1998.15.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bell MJ, Robertson CS, Kochanek PM, Goodman JC, Gopinath SP, Carcillo JA, et al. Interstitial brain adenosine and xanthine increase during jugular venous oxygen desaturations in humans after traumatic brain injury. Crit Care Med. 2001;29(2):399–404. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200102000-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fedorova IM, Jacobson MA, Basile A, Jacobson KA. Behavioral characterization of mice lacking the A3 adenosine receptor: sensitivity to hypoxic neurodegeneration. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2003;23(3):431–447. doi: 10.1023/A:1023601007518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chen GJ, Harvey BK, Shen H, Chou J, Victor A, Wang Y. Activation of adenosine A3 receptors reduces ischemic brain injury in rodents. J Neurosci Res. 2006;84(8):1848–1855. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zheng W, Talley Watts L, Sayre NL, Holstein D, Lechleiter JD. Targeting Astrocyte Mitochondrial ATP production as a Strategy to Treat Brain Injuries. In: Sontheimer H, editor. Glial Biology in Medicine; Birmingham, AB2012.

- 64.Li X, Zima AV, Sheikh F, Blatter LA, Chen J. Endothelin-1-induced arrhythmogenic Ca2+ signaling is abolished in atrial myocytes of inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate(IP3)-receptor type 2-deficient mice. Circ Res. 2005;96(12):1274–1281. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000172556.05576.4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Petravicz J, Fiacco TA, McCarthy KD. Loss of IP3 receptor-dependent Ca2+ increases in hippocampal astrocytes does not affect baseline CA1 pyramidal neuron synaptic activity. J Neurosci. 2008;28(19):4967–4973. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5572-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wahlman C, Doyle TM, Little JW, Luongo L, Janes K, Chen Z, et al. Chemotherapy-induced pain is promoted by enhanced spinal adenosine kinase levels through astrocyte-dependent mechanisms. Pain. 2018;159(6):1025–1034. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tosh DK, Finley A, Paoletta S, Moss SM, Gao ZG, Gizewski ET, et al. In vivo phenotypic screening for treating chronic neuropathic pain: modification of C2-arylethynyl group of conformationally constrained A3 adenosine receptor agonists. J Med Chem. 2014;57(23):9901–9914. doi: 10.1021/jm501021n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jacobson KA, Giancotti LA, Lauro F, Mufti F, Salvemini D. Treatment of chronic neuropathic pain: purine receptor modulation. Pain. 2020;161(7):1425–1441. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ochaion A, Bar-Yehuda S, Cohen S, Barer F, Patoka R, Amital H, et al. The anti-inflammatory target A(3) adenosine receptor is over-expressed in rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis and Crohn’s disease. Cell Immunol. 2009;258(2):115–122. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2009.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Delmas P, Brown DA. Pathways modulating neural KCNQ/M (Kv7) potassium channels. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6(11):850–862. doi: 10.1038/nrn1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gamper N, Shapiro M. KCNQ Channels. In: Zheng J, Trudeau M, editors. Handbook of Ion Channels. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2015.

- 72.Wickenden AD, Yu W, Zou A, Jegla T, Wagoner PK. Retigabine, a novel anti-convulsant, enhances activation of KCNQ2/Q3 potassium channels. Mol Pharmacol. 2000;58(3):591–600. doi: 10.1124/mol.58.3.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rundfeldt C. The new anticonvulsant retigabine (D-23129) acts as an opener of K+ channels in neuronal cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 1997;336(2–3):243–249. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01249-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Boscia F, Annunziato L, Taglialatela M. Retigabine and flupirtine exert neuroprotective actions in organotypic hippocampal cultures. Neuropharmacology. 2006;51(2):283–294. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2006.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Amabile CM, Vasudevan A. Ezogabine: a novel antiepileptic for adjunctive treatment of partial-onset seizures. Pharmacotherapy. 2013;33(2):187–194. doi: 10.1002/phar.1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gilman AG. G proteins: transducers of receptor-generated signals. Annu Rev Biochem. 1987;56:615–649. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.56.070187.003151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Abbracchio MP, Brambilla R, Ceruti S, Kim HO, von Lubitz DK, Jacobson KA, et al. G protein-dependent activation of phospholipase C by adenosine A3 receptors in rat brain. Mol Pharmacol. 1995;48(6):1038–1045. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data and materials used in this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.