Abstract

To halt the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) epidemic requires interventions that can prevent transmission of numerous HIV-1 subtypes. The most frequently transmitted viruses belong to the subtypes A, B, and C and the circulating recombinant forms (CRFs) AE and AG. A fast one-tube assay that identifies and distinguishes among subtypes A, B, and C and CRFs AE and AG of HIV-1 was developed. The assay amplifies a part of the gag gene sequence of the genome of all currently known HIV-1 subtypes and can identify and distinguish among the targeted subtypes as the reaction proceeds, because of the addition of subtype-specific molecular beacons with multiple fluorophores. The combination of isothermal nucleic acid sequence-based amplification and molecular beacons is a new approach in the design of real-time assays. To obtain a sufficiently specific assay, we developed a new strategy in the design of molecular beacons, purposely introducing mismatches in the molecular beacons. The subtype A and CRF AG isolates reacted with the same molecular beacon. We tested the specificity and sensitivity of the assay on a panel of the culture supernatant of 34 viruses encompassing all HIV-1 subtypes: subtypes A through G, CRF AE and AG, a group O isolate, and a group N isolate. Assay sensitivity on this panel was 92%, with 89% correct subtype identification relative to sequence analysis. A linear relationship was found between the amount of input RNA in the reaction mixture and the time that the reaction became positive. The lower detection level of the assay was approximately 103 copies of HIV-1 RNA per reaction. In 38% of 50 serum samples from HIV-1-infected individuals with a detectable amount of virus, we could identify subtype sequences with a specificity of 94% by using sequencing and phylogenetic analysis as the “gold standard.” In conclusion, we showed the feasibility of the approach of using multiple molecular beacons labeled with different fluorophores in combination with isothermal amplification to identify and distinguish subtypes A, B, and C and CRFs AE and AG of HIV-1. Because of the low sensitivity, the assay in this format would not be suited for clinical use but can possibly be used for epidemiological monitoring as well as vaccine research studies.

Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) can be differentiated into several genetic groups and subgroups, or subtypes. The viral isolates that belong to the genetic group M are responsible for more than 99% of all infections worldwide. This group can be divided into subtypes A through H, to which subtype K was recently added (32). As for subtype J, only two strains are known, whereas subtype I appears to be a mosaic of various subtypes. Besides the group M isolates, the groups N and O are also recognized (9, 34). Isolates that belong to these two groups are mainly found in patients in Cameroon, whereas group M isolates can be found worldwide, with distinct subtypes dominant in specific geographical areas. Epidemiological data is continuously being collected to monitor the dynamics of global subtype distribution and the emergence of new subtypes for the purpose of vaccine research and evaluation. A limited number of subtypes dominate the global epidemic. The most dominant is subtype C, closely followed by subtype A and its circulating recombinant forms (CRFs) AE and AG. In the Americas and Europe, subtype B is still dominant.

In clinical diagnostics, the viral RNA level in serum or plasma obtained from HIV-1-infected individuals is the prime determinant of disease progression and therefore provides a strong indication of the success or failure of antiretroviral drug therapy (11, 18, 23, 24, 33). In general, persistently low viral RNA levels are associated with slow disease progression, while persistently high levels are associated with rapid disease progression. The accurate assessment of viral RNA levels is highly dependent on the amplification technology used. Such technologies are sensitive to genetic variation and variability of the target regions within the genes of interest. Several subtypes are undetected or poorly detected by certain viral RNA assays, due to mismatches of primers and probes with the target regions of the assays (1, 7, 8, 27). Underestimation of viral RNA levels affects not only the evaluation of antiretroviral drug therapies against infections with non-B subtypes, but also the effectiveness of therapeutic interventions in blocking mother-to-child transmission. The same applies to future vaccine trials.

We previously described an assay that universally detected and quantified group M, N, and O viruses (7a). To identify the infecting subtype, we have now designed and evaluated a new assay. Since non-B HIV-1 infections currently dominate the AIDS pandemic and virus variation increases during the course of the epidemic, monitoring of subtype distribution requires easy-to-use serum assays. Antibody tests with subtype-specific peptides have been developed (2, 4, 29), but while able to exclude certain subtypes, these assays cannot always positively identify a subtype (26, 30). The preferred method is, therefore, nucleic acid subtyping, in which the genetic subtype of an isolate is determined largely by sequencing (a part of) the viral genome and using phylogenetic analysis to compare it with a set of reference sequences having a known subtype. This “gold standard” assay is cumbersome, labor intensive, and time consuming, and the reagents are expensive. Another much easier but still time-consuming technique is subtype determination by heteroduplex mobility assay (HMA) (10, 17). Both sequencing and HMA analysis involve isolation of HIV-1 RNA or DNA and the amplification of a target sequence by PCR, followed by a nested PCR. These PCR templates are used either for the sequencing and analysis step or for the HMA analysis.

To reduce time and laborious work, our assay was designed to detect and identify the major globally circulating subtypes—subtype A and its CRF AG and subtypes B and C and the CRF AE—in one amplification reaction (42). The subtype A and CRF AG isolates are not distinguished from each other, since they react with the same molecular beacon. The assay is based on nucleic acid sequence-based amplification (NASBA) technology combined with the use of subtype-specific hybridizing molecular beacons for detection and discrimination. NASBA amplification is known to be a powerful tool for the amplification of single-stranded HIV-1 RNA molecules (7, 16, 38), whereas molecular beacons have been proven useful in discriminating among different targets (41). Compared to other assays, which discriminate different targets that are amplified by multiple primer pairs, our assay discriminates subtype-specific determinants within one target that is amplified by a single primer pair.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The subtype identification assay.

A standard NASBA reaction scheme was applied to the subtype differentiation assay. Each reaction mixture consisted of 5 μl of purified sample RNA and 10 μl of NASBA reaction mixture. This NASBA mixture consisted of 80 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.5); 24 mM MgCl2; 140 mM KCl; 1.0 mM dithiothreitol; 2.0 mM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate; and 4.0 mM (each) ATP, UTP, CTP, and GTP in 30% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). This solution also contained 2.0 μM (each) antisense and sense primers for amplification and the molecular beacons for detection. The sequences of the primers and the beacons are summarized in Table 1. Each beacon was labeled with a different fluorophore for discrimination: tetrachloro-6-carboxyfluorescein for the subtype A and CRF AG beacon, 6-carboxy-X-rhodamine for the subtype B beacon, fluorescein for the subtype C beacon, and tetramethylrhodamine for the CRF AE beacon. All molecular beacons used 4-((4-(dimethylamino)phenyl) azo)benzoic acid as universal quencher.

TABLE 1.

Sequences of the primers and the subtype-specific molecular beacons, as well as the 5′ fluorophore of each molecular beacon

| Name | Nucleotide sequencea | Fluorophoreb | Final reaction concn (nM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Promoter (T7) | AATTCTAATACGACTCACTATAGGG | ||

| Primer | |||

| Sense P2 | TGCTATGTCACTTCCCCTTGGTTCTCTCA | 50 | |

| Antisense P1 | T7-AGTGGGGGGACATCAAGCAGCCATGCAAA | 50 | |

| Beacon (subtype and/or CRF) | |||

| A-CRF AG | CGTACGTGGGACAGGITACAGCCAGCGTACG | TET | 10 |

| B | CGATCGTGCAGAATGGGATAGATTGCGATCG | ROX | 100 |

| C | CGTACGATCAATGAAGAGGCTGCACGTACG | FAM | 10 |

| CRF AE | CGTACGGATAGGGTACACCCAGTACACGTACG | TAMRA | 30 |

The T7 promoter recognition sequence is depicted at the top in italics; the nucleotides that form the stem of the typical stem-and-loop structure of the molecular beacon are underlined.

TET, tetrachloro-6-carboxyfluorescein; ROX, 6-carboxy-X-rhodamine; FAM, fluorescein; TAMRA, tetramethylrhodamine.

The reaction mixtures were incubated at 65°C for 2 min, and after being cooled to 41°C for 2 min, 5 μl of enzyme mixture was added. This mixture contained (per reaction) 375 mM sorbitol, 2.1 μg bovine serum albumin, 0.08 U RNase H, 32 U of T7 RNA polymerase, and 6.4 U of avian myeloblootosis virus reverse transcriptase (RT). Reactions were incubated at 41°C for 60 min in an ABI7700 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) for real-time monitoring (i.e., as the reaction proceeds) of the amplification reaction at the wavelengths that are specific for the fluorophores we used.

Samples.

For preclinical evaluation and development of the assay, we purified RNA from the supernatant of certain cultured viral isolates, using a silica-based isolation method (3). This collection encompassed a total of 35 viral isolates (in parentheses): group M subtypes A (4), B (7), C (5), D (3), F (3), and G (1); group M CRFs AE (8) and AG (2); group O (ANT70) (1); and group N isolate (YBF30) (1). A clinical evaluation of the sera of 50 HIV-1-infected individuals was performed. These individuals were selected from the outpatient clinic of the Academic Medical Center in Amsterdam, The Netherlands, and their serum had a known subtype based on the part of the gag gene containing p17 and half of p24 (7). Briefly, the HIV-1 subtypes of the isolates were determined by phylogenetic analysis with the Kimura two-parameter model to calculate the distance matrix (20) and the neighbor-joining method, as implemented with the TREECON program (37). The analysis included a set of reference sequences that were downloaded from the Internet (http://hiv-web.lanl.gov/). Our collection encompassed 50 serum samples from HIV-1-infected individuals infected with isolates of subtype A (5 samples), B (9), C (7), D (9), F (1), and G (6), as well as CRF AE (2), and CRF AG (11). From each of these isolates, a gag sequence was obtained for phylogenetic analysis to identify the subtype, as well as for alignment against the primers and molecular beacons used in the subtype determination assay for mismatch analysis, as has been previously described (7).

Viral RNA assays.

Viral RNA levels in the 50 serum samples were determined by using a commercially available assay, the NucliSens HIV-1 RNA QT assay (Organon-Teknika, Boxtel, The Netherlands), or a broad-subtype long terminal repeat-based viral RNA assay (Retina assay) (7a).

Statistical analysis.

All statistical analyses were performed with the SPSS version 10.0.5 software package (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, Ill.).

RESULTS

Design of the subtype identification assay.

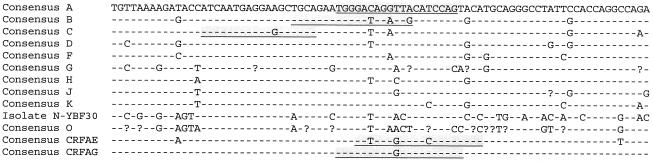

The p17-p24 region of the gag gene of the HIV-1 genome contains sufficient variation in genetic information to allow discrimination among subtypes in a phylogenetic analysis of the sequences (Fig. 1). This region was selected for development of an assay that could discriminate between different subtypes by using probes that hybridize with subtype-specific sequences and that are distinguishable by the use of different fluorescent reporter labels. The sequence variations in the gag target are revealed by the alignment of the consensus sequences of the subtypes A through H and the CRFs AE and AG (Fig. 2).

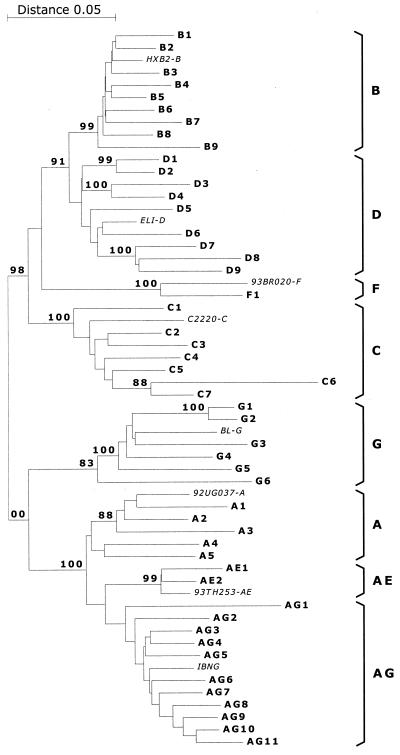

FIG. 1.

Phylogenetic tree after analysis of sequences from the p17-p24 region of the gag gene. Sequences were obtained after RT-PCR of RNA isolated from the serum of HIV-1-infected individuals. The various subtype and CRF clusters are bracketed at right.

FIG. 2.

Alignment of consensus sequences from the depicted subtypes of the region that is amplified by the subtype identification assay. Underlined in shaded boxes are the sequences that functioned as target sequences for the design of the subtype-specific molecular beacons. The consensus sequences were derived from sequence data from sequence data from the Los Alamos National Laboratory (http://hiv-web.lanl.gov/).

The type of probes used for discrimination of subtypes were molecular beacons, which have their fluorescent label at one end and a nonfluorescent quencher at the other end. Molecular beacons fluoresce only when they bind to their target sequence (36).

We designed molecular beacons that could discriminate between the subtypes A, B, and C and CRFs AE and AG; however, the subtype A and CRF AG isolates reacted with one molecular beacon, since they are genetically identical in the hybridization region of the beacon (Fig. 2) (http://hiv-web.lanl.gov/).

Using sequences from each subtype or CRF available from the Los Alamos National Laboratory HIV sequence database (http://hiv-web.lanl.gov/), we designed molecular beacons in the gag region of the HIV-1 genome between position 1388 and 1471, based on the HXB2R sequence (GenBank accession number K03455). The gag region is efficiently amplified in a NASBA reaction by primers described previously (19, 38, 39). Each NASBA reaction typically results in large amounts of negative-stranded RNA if the target RNA is positive stranded, as is the case with HIV-1. The molecular beacons in the reaction hybridize with their complementary sequences instantly upon synthesis of the negative-stranded RNA, enabling real-time detection. The beacons determined the specificity of the assay, since the primers amplified RNA from virtually any HIV-1 isolate (15).

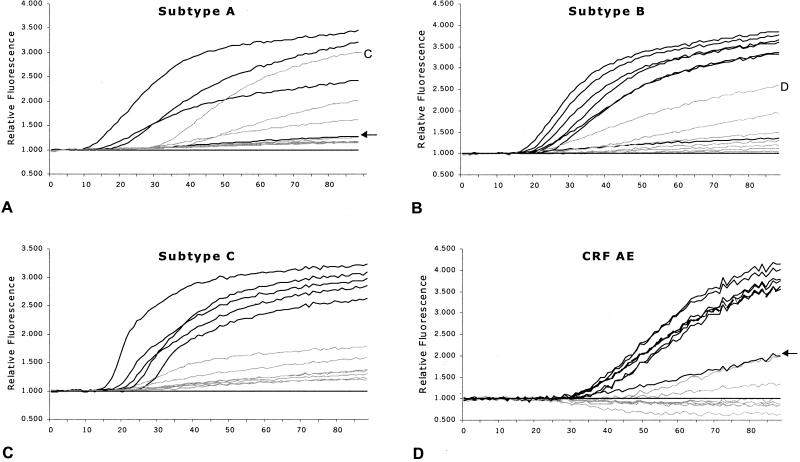

The molecular beacons designed to detect subtype B and CRF AE isolates were highly specific. The beacons for the subtypes A-CRF AG and subtype C reacted with the targeted subtype isolates but also with other subtype isolates, as shown in Fig. 3A for the subtype C molecular beacon. These beacons were designed to discriminate between the targeted subtype isolates and the excluded subtype isolates on the basis of only a single nucleotide. To enhance the specificity of these molecular beacons, we incorporated a deliberate mismatch two or three nucleotide positions from the discriminating nucleotide. The resulting molecular beacons contained one mismatch for the targeted subtype isolates and at least two mismatches, close to each other, for any other subtype isolates. The beacons could distinguish between the targeted subtype sequences and sequences from the other subtype isolates, as shown in Fig. 3B for the subtype C molecular beacon.

FIG. 3.

Amplification curve of one subtype A, B, C, or D and CRF AE isolate as detected with the subtype C molecular beacon (A) before enhancement of specificity; amplification curve of the same isolates, as detected with the more specific subtype C molecular beacon (B). Relative fluorescence is shown on the y axes, and time (in minutes) is shown on the x axes. In both panels, the subtype C isolates are plotted with a heavy line.

In the sequence to which the subtypes A-CRF AG molecular beacon hybridized, one position varied between nucleotides T and G. Therefore, in the design an inosine was incorporated in the molecular beacon at the variable position, which resulted in an A-CRF AG-specific beacon targeted to all sequences of those two subtypes.

Subtype-specific reactivity of the molecular beacons.

A well-characterized and calibrated panel of 30 isolates (in parentheses) encompassing viral culture supernatant from subtypes A (1), B (7), C (5), D (3), F (3), and G (1), as well as the CRFs AE (8) and AG (2), has been described before (25) and was tested with our subtype identification assay. This panel was expanded with three subtype A samples (UG29, UG31, and RW20) from the collection of the WHO Network for HIV Isolation and Characterization, described earlier (6), so that a total of four subtype A samples was analyzed. Additionally, we tested a group O (ANT70) isolate and a group N (YBF30) isolate. Figure 4 shows the results from each specific molecular beacon with the isolates it should distinguish, together with the background curve of one representative isolate of each other subtype or CRF, plus one no-template reaction. The subtype A-CRF AG molecular beacon reacted with one subtype C isolate, and the subtype B molecular beacon reacted with one subtype D isolate. One subtype A isolate and one CRF AE isolate were not detected by the corresponding molecular beacons, and both fluorescence curves are indicated (Fig. 4A and D). The sensitivity of the assay according to the supernatant panel was 92% (24 of 26 isolates correctly identified), and the specificity was 89%, both values relative to the subtype as assigned after sequencing and phylogenetic analysis (see Fig. 1). Two isolates were wrongly detected by our assay; one was a subtype C isolate, ET2220, that reacted positively with both the subtype A-CRF AG and subtype C molecular beacons, and one was a subtype D isolate that reacted with the subtype B molecular beacon. For our specificity analysis, the subtype C isolate was scored as correctly identified, since it also reacted with the subtype C molecular beacon.

FIG. 4.

Amplification curves of the various isolates from a panel of culture supernatants of HIV-1 subtypes A, B, and C and CRFs AE and AG. Depicted with black lines are the fluorescence curves for the isolates that should react with the molecular beacons for subtype A-CRF AG (A), subtype B (B), subtype C (C), and CRF AE (D), including a representative nonreactive isolate from each subtype (grey lines). The no-template reactions were used to calculate the relative fluorescence of each of the samples and are represented by the black line at 1.000 (y axis). Time (in minutes) is shown on the x axes. The arrows in panels A and D indicate isolates that were not positively detected but belonged phylogenetically to the subtype that was analyzed in the respective panels.

The linear relationship between the amount of input RNA and the time-to-positive signal for subtype A-CRF AG, B, C, and CRF AE isolates.

To analyze the semiquantitative aspect of the subtype discrimination assay, one isolate each of subtypes A, B, and C and a CRF AE isolate were taken and tested in ten-fold serial dilutions. The input of RNA molecules was assessed by the Retina assay, which is a broad-subtype HIV-1 RNA quantification assay (7a). The results correlated with the published RNA levels as measured by the Amplicor HIV-1 RNA assay, version 1.5 (Roche Molecular Diagnostics, Branchburg, N.J.) (7a, 25). For the subtype A, B, and C isolates, there was a linear relationship between input RNA and the time-to-positive signal in each case, with approximately 103.5 to 107.5 copies of viral RNA molecules per reaction. The assay had a lower detection level of approximately 103 copies of viral RNA per reaction. For the CRF AE isolate, the time-to-positive signal occurred later than with other subtypes, despite a similar change in input of RNA copies per reaction mixture, indicating that either the amplification or the detection of the CRF AE isolates was less efficient.

Clinical evaluation of the subtype discrimination assay.

We tested a panel of 50 serum samples, encompassing the subtypes A (5 samples), B (9), C (7), D (9), F (1), and G (6) and CRFs AE (2) and AG (11), as determined by sequencing and phylogenetic analysis of a part of the gag gene (Fig. 1). These samples have been described before, and all contained detectable amounts of HIV-1 RNA based on the Retina assay, which levels of RNA had a high correlation (R2 = 0.74) with the results obtained by the NucliSens assay for those subtypes that could reliably be tested by both assays (7a).

Of the 16 subtype A and CRF AG viruses in serum, 2 subtype A viruses and 2 CRF AG viruses (ranging from 3.0 to 3.8 log10 RNA copies per input) were positive with the subtype A-CRF AG molecular beacon. The three negative subtype A viruses and nine negative CRF AG viruses had input RNA levels ranging from <1.7 to 3.5 log10 copies per reaction. Of the nine subtype B viruses, five were positive (RNA levels between 2.4 to 3.3 log10 RNA copies per reaction) with the subtype B molecular beacon, and four were negative with RNA levels between 2.3 to 3.7 log10 RNA copies per reaction. Of the seven subtype C viruses, four were positive with the subtype C molecular beacon, with RNA levels between 2.3 to 2.8 log10 copies per reaction. For the three negative serum samples that contained subtype C viruses, the input was 1.6, 1.8, and 4.8 log10 RNA copies per reaction, respectively. The two CRF AE viruses (2.2 and 2.3 log10 RNA copies per input) were both not detectable with the CRF AE nor any molecular beacon. One subtype D virus reacted with the subtype A-CRF AG molecular beacon.

Taking all the samples together, 13 of 14 positive samples (92.9%) were identified by the subtype identification assay with the same result as by sequence analysis. All these isolates contained viral RNA levels ranging from 2.3 and 3.8 log10 copies per reaction. In total, 34 samples were identified as subtype A, B, or C or CRF AE or AG based on their sequence, and 21 of these 34 (62%) could not be detected by the subtype identification assay. These 21 samples contained viral RNA levels between <1.0 and 4.8 log10, with a median of 2.2 log10 RNA copies per reaction. In summary, the sensitivity of the assay for this panel was 38%, with a specificity of 94%. It should be noted that one of the correctly identified subtype C isolates was also positive with the subtype B molecular beacon, whereas one subtype B isolate reacted with both the subtype B and subtype C molecular beacons. For the sensitivity and specificity analyses, these samples were scored subtype C and subtype B, respectively.

Analysis of mismatches for molecular beacons in preclinical and clinical evaluation.

The two samples that yielded false-positive results were one subtype D virus isolated from culture supernatant that reacted with the subtype B molecular beacon and one subtype D virus isolated from serum that reacted with the subtype A-CRF AG molecular beacon. The sequences of the target region of these two isolates were analyzed for mismatches with the molecular beacon hybridizing regions. The sequence of the cultured subtype D isolate contained no mismatches with the subtype B molecular beacon. The subtype D serum sample also showed no mismatches with this molecular beacon, although the design of the subtype A-CRF AG molecular beacon was targeted at a minimum of two mismatches. Therefore, based on their sequences, those isolates rightly reacted with the subtype B and the subtype A-CRF AG molecular beacons and thus were not wrongly identified. As for samples that were not detected at all, either the viral RNA levels were below the detection level of the assay (103 RNA copies per reaction), leading to negative results, or the number of mismatches between target sequences and molecular beacons exceeded two, prohibiting hybridization of the molecular beacons.

DISCUSSION

We have developed a one-tube subtype identification assay that can successfully determine and discriminate HIV-1 viral isolates belonging to subtypes A, B, or C or CRF AE or AG. The assay is based on NASBA technology (16, 38) in combination with molecular beacon probes for real-time monitoring of the amplification reaction and discrimination of the sequences. Discrimination was achieved by adding four different subtype-specific molecular beacons to the reaction mixture, each labeled with its own distinct fluorophore. The reactions were monitored with an ABI7700 sequence detection system that was able to separate the specific signals from the various molecular beacons after they had hybridized to their target (36, 41). Each molecular beacon was designed to hybridize with isolates from one specific subtype. Subtype A and CRF AG, which are genetically closely related and identical in the molecular beacon hybridizing sequence, could not be discriminated from each other but were distinguishable from any of the other isolates.

By introducing a nonspecific mismatch into the hybridizing sequence of the molecular beacons for subtype A-CRF AG and subtype C isolates, we were able to enhance the specificity of these beacons. Without this mismatch, the subtype C beacon could hybridize with any subtype isolate we tested in the development phase, and the subtype A-CRF AG beacon could hybridize with subtype C isolates as well as subtype A-CRF AG. By introducing a nucleotide to create a second mismatch for any of the non-A-CRF AG or non-C isolates, respectively, we enhanced specificity because the two or more mismatches between beacon and nontarget were within a short distance of only two to three nucleotides from each other. This approach can be used to enhance specificity in other hybridization protocols, for example, in the design of PCR or RT-PCR primers, Taqman probes, and sunrise primers. It has been reported that molecular beacons are well suited to distinguish between two sequences based on only one nucleotide difference (22, 35, 36). Our assay allows one mismatch in the hybridizing sequence of the molecular beacon, most likely because of the relatively low temperature at which the NASBA reactions were performed. This temperature was 41°C, but because of the presence of 15% DMSO in the reaction mixture, the effective temperature for primer annealing and molecular beacon hybridization was 48.5°C (2.5°C for each additional 5% of DMSO). Mismatches in hybridizing sequences of primers and probes become more critical at higher temperatures, which was the case for the results with molecular beacons that could make a distinction based on only one nucleotide (22, 35, 36).

Complete or partial sequencing of genes followed by phylogenetic analysis and interpretation (see Fig. 1) is the gold standard for subtype determination. Another frequently used but time-consuming technology with a difficult read-out system is the HMA (10, 17). Whereas subtype assignment by sequencing followed by phylogenetic analysis or by HMA requires a large part of a gene or even the complete gene for significant findings, subtype assignment by our subtype identification assay requires only a small part of the gag gene. None of the techniques as they are intended in their use as described here take recombination into account. This means that although recombination is an increasingly observed phenomenon, the subtype is only determined in the analyzed part of the genome. In this new assay, the part of the gag gene that was amplified, including primer regions, encompassed 212 bases and was even smaller if we took only the area where the molecular beacons hybridized (94 bases). The sensitivity of the subtype identification assay was 92% for a panel of viral supernatant cultures, with a specificity of 89%. The viral RNA levels of this panel all exceeded 105 copies per reaction. Testing a panel of clinical serum samples, in which the viral RNA levels were between 101 and 105 copies per reaction, resulted in 38% sensitivity and specificity of 94%. The difference in the sensitivity numbers between the two panels was due mainly to the lower viral RNA levels of most of the clinical samples relative to those of the cultured isolates. The specificity was molecular beacon dependent and for both panels had a similar range of 90 to 95%.

We found three discordances between the results of subtype assignment by sequencing followed by phylogenetic analysis and the results of our subtype identification assay. Both a subtype C and a subtype D isolate were detected with the subtype A-CRF AG molecular beacon, and one subtype D isolate was detected with the subtype B molecular beacon. Based on the analysis of the sequences, all of these isolates reacted correctly with these molecular beacons, since there were no mismatches besides the general mismatch that was introduced for enhanced specificity of the subtype A-CRF AG molecular beacon. Therefore, the discordances do not reflect a mistake in either the two methods but instead emphasize the difference between the technologies used in sequencing followed by phylogenetic analysis and those used in the subtype identification assay.

The lower detection level of the new assay is approximately 103 RNA copies per reaction, making it less sensitive than assays developed specifically for very sensitive RNA detection (5, 7, 13, 28). The primers used in the subtype identification assay have been used and characterized extensively, and their sensitivity reportedly allows detection below 10 RNA copies per reaction (28). Therefore, the diminishing sensitivity between what is possible with these primers and what we obtained most likely occurred during the detection step, probably because of data reduction. Each of the four fluorescence signals had to be extracted from the entire measured spectrum. Since the signals overlapped each other in the emission spectrum, the extraction algorithms considerably reduced the specific signal emitted by each fluorophore. Therefore, we hypothesize that using multiple fluorophores within one reaction mixture using the ABI7700 caused the low sensitivity of the assay. The loss of sensitivity due to data reduction could perhaps be mitigated by the use of four fluorophores that differ markedly in their emission spectrum. With a filter-based fluorimeter, these spectra could then be extracted from each other without applying a data reduction algorithm, resulting in improved sensitivity over the use of the ABI7700.

Although the loss in sensitivity seems to be explainable by the overlapping spectra of the fluorophores, it does not explain why some clinical samples with the same subtype and an apparently similar viral RNA level were not consistently positive or negative. One of the reasons for this observation could be the genetic variation between those samples. Although the population sequences reveal similar genetic sequences, at the level of the individual RNA molecules the variation between the probe sequence and the RNA sequence can be higher, which results in a relatively lower amount of detectable RNA molecules. We have not been able to explore this theory.

Since the primers that we used for the amplification reaction were tested in several other studies (7, 28, 38, 40), we could apply part of the resulting data to our assay. For example, these primers were shown not to amplify HIV-1-related viruses, like HIV-2 and human T-cell leukemia virus types 1 and 2. Because we used the same primers and additionally a highly specific molecular beacon, we did not test our assay for cross-reactivity with any of these viruses, being highly confident that no amplification of such viruses would occur.

A major focus of HIV-1 research within the next decade will be the development of one or more vaccines that have broad-subtype coverage. Such a vaccine preferably would be not only prophylactic but also therapeutic by downwards modulating the viral RNA levels of the infected individual, thereby preventing vertical and horizontal transmission as well as delaying disease progression (11, 14, 18, 23, 24, 31). To test vaccines as well as mother-to-child transmission breakthroughs, the detection of HIV-1 RNA is the most accurate and reliable method. If broad-subtype coverage is being investigated, a fast and relatively inexpensive way of subtype determination like our subtype identification assay might be helpful.

In summary, we have developed an HIV-1 subtype identification assay that can accurately determine the presence of subtypes A, B and C and CRF AE and AG viral isolates in culture supernatant or in the serum or plasma of infected individuals. Besides the relevance of this assay for clinical diagnostics, it may assist in vaccine and antiretroviral drug development. Finally, this paper is the first to show the use of four different molecular beacons that all hybridize within their specific context to a similar amplicon, which is generated by the use of only one primer pair for all targets. We have shown that existing molecular diagnostic tools can be combined with state-of-the-art technology to improve and expand clinical diagnostics in existing and new fields.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Maaike van Dooren, Ingrid van Schaik, and Irene Bosboom for excellent technical assistance. We are grateful to Tony de Ronde for critical reading of the manuscript and many helpful discussions and to Lucy Phillips for editorial review.

The group N isolate, YBF30, that was isolated by F. Simon, Hôpital Bichat, Paris, France, was obtained from the NIBSC Centralised Facility for AIDS Reagents, supported by EU Programme EVA (contract BMH 97/2515) and the UK Medical Research Council.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alaeus A, Lidman K, Sonnerborg A, Albert J. Subtype-specific problems with quantification of plasma HIV-1 RNA. AIDS. 1997;11:859–865. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199707000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barin F, Lahbabi Y, Buzelay L, Lejeune B, Baillou-Beaufils A, Denis F, Mathiot C, M'Boup S, Vithayasai V, Dietrich U, Goudeau A. Diversity of antibody binding to V3 peptides representing consensus sequences of HIV type 1 genotypes A to E: an approach for HIV type 1 serological subtyping. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1996;12:1279–1289. doi: 10.1089/aid.1996.12.1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boom R, Sol C J, Salimans M M, Jansen C L, Wertheim-van Dillen P M, Van der Noordaa J. Rapid and simple method for purification of nucleic acids. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:495–503. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.3.495-503.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheingsong-Popov R, Osmanov S, Pau C P, Schochetman G, Barin F, Holmes H, Francis G, Ruppach H, Dietrich U, Lister S, Weber J. Serotyping of HIV type 1 infections: definition, relationship to viral genetic subtypes, and assay evaluation. UNAIDS Network for HIV-1 Isolation and Characterization. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1998;14:311–318. doi: 10.1089/aid.1998.14.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collins M L, Irvine B, Tyner D, Fine E, Zayati C, Chang C, Horn T, Ahle D, Detmer J, Shen L P, Kolberg J, Bushnell S, Urdea M S, Ho D D. A branched DNA signal amplification assay for quantification of nucleic acid targets below 100 molecules/ml. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:2979–2984. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.15.2979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cornelissen M, Kampinga G, Zorgdrager F, Goudsmit J the UNAIDS Network for HIV Isolation and Characterization. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtypes defined by env show high frequency of recombinant gag genes. J Virol. 1996;70:8209–8212. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.11.8209-8212.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Baar M P, van der Schoot A M, Goudsmit J, Jacobs F, Ehren R, van der Horn K H, Oudshoorn P, De Wolf F, De Ronde A. Design and evaluation of a human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA assay using nucleic acid sequence-based amplification technology able to quantify both group M and O viruses by using the long terminal repeat as target. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:1813–1818. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.6.1813-1818.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7a.de Baar M P, van Dooren M W, de Rooij E, Bakker M, Van Gemen B, Goudsmit J, de Ronde A. Single rapid real-time monitored isothermal RNA amplification assay for quantification of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates from groups M, N, and O. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:1378–1384. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.4.1378-1384.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Debyser Z, Van Wijngaerden E, Van Laethem K, Beuselinck K, Reynders M, De Clercq E, Desmyter J, Vandamme A M. Failure to quantify viral load with two of the three commercial methods in a pregnant woman harboring an HIV type 1 subtype G strain. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1998;14:453–459. doi: 10.1089/aid.1998.14.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Leys R, Vanderborght B, Vanden Haesevelde M, Heyndrickx L, van Geel A, Wauters C, Bernaerts R, Saman E, Nijs P, Willems B, Taelman H, van der Groen G, Plot P, Tersmette T, Huisman J G, Van Heuverswyn H. Isolation and partial characterization of an unusual human immunodeficiency retrovirus from two persons of west-central African origin. J Virol. 1990;64:1207–1216. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.3.1207-1216.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Delwart E L, Shpaer E G, Louwagie J, McCutchan F E, Grez M, Rubsamen-Waigmann H, Mullins J I. Genetic relationships determined by a DNA heteroduplex mobility assay: analysis of HIV-1 env genes. Science. 1993;262:1257–1261. doi: 10.1126/science.8235655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Wolf F, Spijkerman I, Schellekens P T, Langendam M, Kuiken C, Bakker M, Roos M, Coutinho R, Miedema F, Goudsmit J. AIDS prognosis based on HIV-1 RNA, CD4+ T-cell count and function: markers with reciprocal predictive value over time after seroconversion. AIDS. 1997;11:1799–1806. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199715000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Erali M, Hillyard D R. Evaluation of the ultrasensitive Roche Amplicor HIV-1 monitor assay for quantitation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:792–795. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.3.792-795.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garcia P M, Kalish L A, Pitt J, Minkoff H, Quinn T C, Burchett S K, Kornegay J, Jackson B, Moye J, Hanson C, Zorrilla C, Lew J F. Maternal levels of plasma human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA and the risk of perinatal transmission. Women and Infants Transmission Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:394–402. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199908053410602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gobbers E, Fransen K, Oosteriaken T, Janssens W, Heyndrickx L, Ivens T, Vereecken K, Schoones R, van de Wiei P, van der Groen G. Reactivity and amplification efficiency of the NASBA HIV-1 RNA amplification system with regard to different HIV-1 subtypes. J Virol Methods. 1997;66:293–301. doi: 10.1016/s0166-0934(97)00072-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guatelli J C, Whitfield K M, Kwoh D Y, Barringer K J, Richman D D, Gingeras T R. Isothermal, in vitro amplification of nucleic acids by a multienzyme reaction modeled after retroviral replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:1874–1878. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.5.1874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heyndrickx L, Janssens W, Zekeng L, Musonda R, Anagonou S, Van der Auwera G, Coppens S, Vereecken K, De Witte K, Van Rampelbergh R, Kahindo M, Morison L, McCutchan F E, Carr J K, Albert J, Essex M, Goudsmit J, Asjö B, Salminen M, Buvé A, van der Groen G Study Group on Heterogeneity of HIV Epidemics in African Cities. Simplified strategy for detection of recombinant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 group M isolates by gag/env heteroduplex mobility assay. J Virol. 2000;74:363–370. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.1.363-370.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jurriaans S, Van Gemen B, Weverling G J, Van Strijp D, Nara P, Coutinho R, Koot M, Schuitemaker H, Goudsmit J. The natural history of HIV-1 infection: virus load and virus phenotype independent determinants of clinical course? Virology. 1994;204:223–233. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kievits T, van Gemen B, van Strijp D, Schukkink R, Dircks M, Adriaanse H, Malek L, Sooknanan R, Lens P. NASBA isothermal enzymatic in vitro nucleic acid amplification optimized for the diagnosis of HIV-1 infection. J Virol Methods. 1991;35:273–286. doi: 10.1016/0166-0934(91)90069-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kimura M. A simple method for estimating evolutionary rates of base substitution through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J Mol Evol. 1980;16:111–120. doi: 10.1007/BF01731581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marras S A, Kramer F R, Tyagi S. Multiplex detection of single-nucleotide variations using molecular beacons. Genet Anal. 1999;14:151–156. doi: 10.1016/s1050-3862(98)00018-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mellors J W, Kingsley L A, Rinaldo C R, Jr, Todd J A, Hoo B S, Kokka R P, Gupta P. Quantitation of HIV-1 RNA in plasma predicts outcome after seroconversion. Ann Intern Med. 1995;122:573–579. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-122-8-199504150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mellors J W, Rinaldo C R, Jr, Gupta P, White R M, Todd J A, Kingsley L A. Prognosis in HIV-1 infection predicted by the quantity of virus in plasma. Science. 1996;272:1167–1170. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5265.1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Michael N L, Herman S A, Kwok S, Dreyer K, Wang J, Christopherson C, Spadoro J P, Young K K, Polonis V, McCutchan F E, Carr J, Mascola J R, Jagodzinski L L, Robb M L. Development of calibrated viral load standards for group M subtypes of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and performance of an improved AMPLICOR HIV-1 MONITOR test with isolates of diverse subtypes. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:2557–2563. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.8.2557-2563.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nkengasong J N, Willems B, Janssens W, Cheingsong-Popov R, Heyndrickx L, Barin F, Ondoa P, Fransen K, Goudsmit J, van der Groen G. Lack of correlation between V3-loop peptide enzyme immunoassay serologic subtyping and genetic sequencing. AIDS. 1998;12:1405–1412. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199812000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nolte F S, Boysza J, Thurmond C, Clark W S, Lennox J L. Clinical comparison of an enhanced-sensitivity branched-DNA assay and reverse transcription-PCR for quantitation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA in plasma. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:716–720. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.3.716-720.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Notermans D W, De Wolf F, Oudshoorn P, Cuijpers H T, Pirillo M, Tiller F W, McClernon D R, Prins J M, Lange J M A, Danner S A, Goudsmit J, Jurriaans S. Evaluation of a second-generation nucleic acid sequence-based amplification assay for quantification of HIV type 1 RNA and the use of ultrasensitive protocol adaptations. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 2000;16:1507–1517. doi: 10.1089/088922200750006038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ondoa P, Willems B, Fransen K, Nkengasong J, Janssens W, Heyndrickx L, Zekeng L, Ndumbe P, Simon F, Saragosti S, Gurtler L, Peeters M, Korber B, Goudsmit J, van der Groen G. Evaluation of different V3 peptides in an enzyme immunoassay for specific HIV type 1 group O antibody detection. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1998;14:963–972. doi: 10.1089/aid.1998.14.963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Plantier J C, Damond F, Lasky M, Sankale J L, Apetrei C, Peeters M, Buzelay L, M'Boup S, Kanki P, Delaporte E, Simon F, Barin F. V3 serotyping of HIV-1 infection: correlation with genotyping and limitations. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1999;20:432–441. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199904150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Quinn T C, Wawer M J, Sewankambo N, Serwadda D, Li C, Wabwire-Mangen F, Meehan M O, Lutalo T, Gray R H. Viral load and heterosexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Rakai Project Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:921–929. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200003303421303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Robertson D L, Anderson J P, Bradac J A, Carr J K, Foley B, Funkhouser R K, Gao F, Hahn B H, Kalish M L, Kuiken C, Learn G H, Leitner T, McCutchan F, Osmanov S, Peeters M, Pieniazek D, Salminen M, Sharp P M, Wolinsky S, Korber B. HIV-1 nomenclature proposal. Science. 2000;288:55–56. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5463.55d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saag M S, Holodniy M, Kuritzkes D R, O'Brien W A, Coombs R, Poscher M E, Jacobsen D M, Shaw G M, Richman D D, Volberding P A. HIV viral load markers in clinical practice. Nat Med. 1996;2:625–629. doi: 10.1038/nm0696-625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Simon F, Mauclere P, Roques P, Loussert-Ajaka I, Muller-Trutwin M C, Saragosti S, Georges-Courbot M C, Barre-Sinoussi F, Brun-Vezinet F. Identification of a new human immunodeficiency virus type 1 distinct from group M and group O. Nat Med. 1998;4:1032–1037. doi: 10.1038/2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tyagi S, Bratu D P, Kramer F R. Multicolor molecular beacons for allele discrimination. Nat Biotechnol. 1998;16:49–53. doi: 10.1038/nbt0198-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tyagi S, Kramer F R. Molecular beacons: probes that fluoresce upon hybridization. Nat Biotechno. 1996;14:303–308. doi: 10.1038/nbt0396-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Van de Peer Y, De Wachter R. TREECON for Windows: a software package for the construction and drawing of evolutionary trees for the Microsoft Windows environment. Comput Appl Biosci. 1994;10:569–570. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/10.5.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Gemen B, Kievits T, Nara P, Huisman H G, Jurriaans S, Goudsmit J, Lens P. Qualitative and quantitative detection of HIV-1 RNA by nucleic acid sequence-based amplification. AIDS. 1993;7(Suppl. 2):S107–S110. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199311002-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Gemen B, Kievits T, Schukkink R, Van Strijp D, Malek L T, Sooknanan R, Huisman H G, Lens P. Quantification of HIV-1 RNA in plasma using NASBA during HIV-1 primary infection. J Virol Methods. 1993;43:177–187. doi: 10.1016/0166-0934(93)90075-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Gemen B, van Beuningen R, Nabbe A, Van Strijp D, Jurriaans S, Lens P, Kievits T. A one-tube quantitative HIV-1 RNA NASBA nucleic acid amplification assay using electrochemiluminescent (ECL) labelled probes. J Virol Methods. 1994;49:157–167. doi: 10.1016/0166-0934(94)90040-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vet J A, Majithia A R, Marras S A, Tyagi S, Dube S, Poiesz B J, Kramer F R. Multiplex detection of four pathogenic retroviruses using molecular beacons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:6394–6399. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.11.6394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Workshop Report from the European Commission (DG XII, INCO-DC); the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. HIV-1 subtypes: implications for epidemiology, pathogenicity, vaccines and diagnostics. AIDS. 1997;11:17–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]