Abstract

This study identified subgenic PCR amplimers from 18S rDNA that were (i) highly specific for the genus Acanthamoeba, (ii) obtainable from all known genotypes, and (iii) useful for identification of individual genotypes. A 423- to 551-bp Acanthamoeba-specific amplimer ASA.S1 obtained with primers JDP1 and JDP2 was the most reliable for purposes i and ii. A variable region within this amplimer also identified genotype clusters, but purpose iii was best achieved with sequencing of the genotype-specific amplimer GTSA.B1. Because this amplimer could be obtained from any eukaryote, axenic Acanthamoeba cultures were required for its study. GTSA.B1, produced with primers CRN5 and 1137, extended between reference bp 1 and 1475. Genotypic identification relied on three segments: bp 178 to 355, 705 to 926, and 1175 to 1379. ASA.S1 was obtained from single amoeba, from cultures of all known 18S rDNA genotypes, and from corneal scrapings of Scottish patients with suspected Acanthamoeba keratitis (AK). The AK PCR findings were consistent with culture results for 11 of 15 culture-positive specimens and detected Acanthamoeba in one of nine culture-negative specimens. ASA.S1 sequences were examined for 6 of the 11 culture-positive isolates and were most closely associated with genotypic cluster T3-T4-T11. A similar distance analysis using GTSA.B1 sequences identified nine South African AK-associated isolates as genotype T4 and three isolates from sewage sludge as genotype T5. Our results demonstrate the usefulness of 18S ribosomal DNA PCR amplimers ASA.S1 and GTSA.B1 for Acanthamoeba-specific detection and reliable genotyping, respectively, and provide further evidence that T4 is the predominant genotype in AK.

The demonstrated pathogenicity for humans and animals of organisms belonging to the genus Acanthamoeba (17, 26), coupled with the difficulty of using morphological criteria for subgeneric identification of isolates (30, 38), has stimulated a number of laboratories to pursue molecular methods for detection and identification. The objective is to develop methods that are suitable for both clinical and environmental applications. The identification of amoebic isolates should be very reliable and, at least for clinical use, the detection system should be very sensitive. Several research groups, including our own, have demonstrated the usefulness of PCR methods for detection of acanthamoebae (10, 15, 21, 25, 27, 40). As few as 1 to 10 trophozoites can be detected. It also is possible to enhance detection of individual amoeba in very dilute liquid clinical samples with fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) (36). Several molecular approaches increase the reliability of specimen identification, but the use of DNA sequence variation appears to be the most promising. The variation is observed in restriction fragment length polymorphisms of complete or partial nuclear 18S rRNA genes (8, 20, 21, 22), of complete mitochondrial 16S rRNA genes (7, 46), and of the complete mitochondrial genome (3, 7, 13, 18, 22, 45). It also is observed in the DNA sequences of complete or partial 18S rRNA genes (10, 27, 35, 41, 42) and in RAPD (randomly amplified polymorphic DNA) analysis of whole-cell DNA (1). At the present time, sequences of the complete 18S rRNA gene appear to provide the most reliable measure of relatedness both because of the number of variable bases in these genes and because of the number of sequences that have been determined. In the present study, we have demonstrated that a PCR primer pair previously described in one of our laboratories (10) produces an amplimer that is reliably specific for the genus Acanthamoeba. The amplimer, now designated ASA.S1 for Acanthamoeba-specific amplimer S1, also has interstrain sequence variation sufficient to distinguish several clusters of 18S rDNA genotypes. This primer pair is used here to analyze a sample of clinical isolates. In order to differentiate individual Acanthamoeba keratitis (AK) genotypes, we used a set of PCR primers that produced a larger amplimer designated GTSA.B1 for the genotype-specific amplimer B1. We then used a multilocus sequencing strategy that enabled us to differentiate all genotypes with a resolution approaching that obtained using the intact gene. This strategy is used here to analyze South African clinical and environmental specimens.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Organisms.

Cultures representing the three morphological groups (30, 38) and the 12 18S ribosomal DNA (rDNA) sequence types (termed genotypes here) of Acanthamoeba (35) were maintained in liquid broth (OGM) as previously described (5). The Scottish corneal scrapes were obtained in a population-based longitudinal study of keratitis in the West of Scotland (33) and were stored in sterile saline. They had been examined previously at Tennent Institute and Ohio State University (OSU) for the presence of acanthamoebae based on culture growth and in situ hybridization with a genus-specific fluorescent oligonucleotide probe (36). The scrape specimens used here for PCR were taken directly from the original saline suspensions. The individual amoeba used here for PCR sensitivity assays were picked off of agar surfaces by applying suction through a rubber hose attached to a Pasteur pipette with a tip drawn out to a small diameter. The South African isolates were cultured at the University of Witwatersrand. The 12 eye and contact lens isolates were collected from patients with AK in South Africa and nearby countries from 1990 to 1995. The three sewage sludge isolates were collected in South Africa in 1987. Subsequently, all three sewage isolates were shown to be highly cytopathogenic to human cells in vitro despite having been kept in axenic culture in the laboratory for a number of years (29).

Control cultures for testing the generic specificity of ASA.S1 amplification were obtained from the following sources. Bacterial, fungal, and algal cultures were from collections maintained at OSU. Cultures of Balamuthia and Leptomyxa spp. were provided by F. L. Schuster, formerly of Brooklyn College, New York, N.Y., and G. S. Visvesvara, U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Ga. Naegleria sp. was donated by Takuro Endo, Japanese National Institutes of Health, Tokyo, Japan.

Nucleic acid extraction and PCR.

Amoebae from 5-ml cultures were harvested and then lysed in 500 μl of UNSET lysis buffer (16). The aqueous lysate was repeatedly extracted with 500-μl volumes of phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol until the protein interface disappeared. The DNA was precipitated from the aqueous lysate with 1 ml of ethanol and then resuspended in 30 to 60 μl of sterile distilled water. Then, 1 μl of the DNA solution was used for PCR amplification of the 18S rDNA diagnostic regions. Alternatively, a modified Chelex procedure (43) was used for clinical samples containing lower numbers of amoebae or for amoebae individually isolated by using a micropipette from agar plate cultures. In this procedure, samples with one or more amoebae were diluted to ∼1 ml in distilled water and then centrifuged for 1 min at ∼16,000 × g in a microfuge. The supernatant was discarded, and the cell pellet was resuspended in 1 ml of double-distilled water, incubated at room temperature for 15 to 30 min, and then recentrifuged for 3 min. All of the supernatant except the last 20 to 30 μl was removed from over the pellet, and fresh 5% Chelex was added to a final volume of 100 μl. The suspension was incubated at 80°C for 15 min, vortexed for 10 s, boiled for 8 min, vortexed another 10 s, and centrifuged for 3 min. The supernatant was removed and immediately used for PCR. A magnesium concentration of 4 mM was used for all PCR reactions. When high sensitivity was required, the reaction mixes were incubated for 7 min at 95°C, followed by 45 cycles of 1 min at 95°C, 1 min at 60°C, and 2 min at 72°C. When a high specificity was required, mixes were incubated for 7 min at 95°C, followed by 20 cycles of 1 min at 95°C, 1 min at 60°C, and 2 min at 72°C. This was followed by 25 cycles of 1 min at 95°C and 2 min at 72°C. All reactions occurred in a laminar flow hood after 20 min of UV irradiation to decontaminate hood surfaces and PCR supplies. Presterilized PCR tubes and aerosol-resistant tips (Continental Lab Products, Tucson, Ariz.) were used to lessen the possibility of contamination.

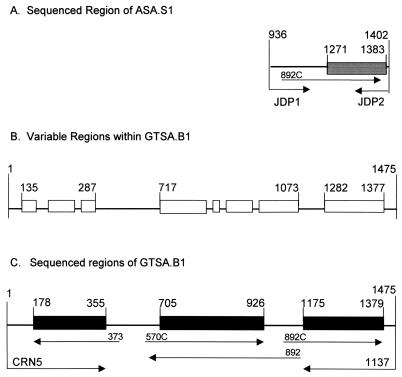

Potential PCR primers were evaluated using the program Oligo (31) to maximize the probability of successful amplification. The Acanthamoeba-specific primer pair used here included the forward primer JDP1 (5′-GGCCCAGATCGTTTACCGTGAA) and the reverse primer JDP2 (5′-TCTCACAAGCTGCTAGGGAGTCA). JDP2 is a modification of ACARNA. 1383 (40) and RGPG (11). The JDP1-JDP2 primer pair previously was shown at OSU to produce the amplimer now designated ASA.S1 from acanthamoebae isolated from tissues of freshwater fishes (10). However, the evidence for genus specificity and for sensitivity of the assay is described here for the first time. Depending on the genotype, the primers amplified ca. 423 to 551 bp of 18S rDNA between reference bp 936 and 1402. Genotype T5 yielded the smallest amplimers and genotypes T7, T8, and T9 the largest. The 18S rDNA sequence of the Neff strain of A. castellanii (14) was used as the reference for all base-pair coordinates cited in this report. The amplified region extended from 18S rRNA secondary structure stems E23-2 to -30 and included 3 of 11 segments that are highly variable in Acanthamoeba (35). The genus specificity was provided by the JDP1 primer that hybridized exclusively to Acanthamoeba 18S rDNA in regions E23-2′ and E-23-6. The sequence was determined for bp 1271 to 1383 using the 892C sequencing primer. This segment included portions of conserved stem 29 and all of 29-1, a stem that is highly variable and greatly expanded in Acanthamoeba. The sequence in region 29-1 provided the genotype discrimination of ASA.S1.

In order to produce an amplimer with enough phylogenetically informative sequence variation to more reliably discriminate between genotypes, we chose a PCR primer pair that would produce a product that included ASA.S1 plus additional variable regions of the 5′ half of the 18S rDNA molecule. A eukaryote-specific primer pair rather than an Acanthamoeba-specific pair was used because we were unable to identify any reliable genus-specific sites at either end of this region. The pair used (44) included the forward primer CRN5 (5′-CTGGTTGATCCTGCCAGTAG), modified from SSU1, at the 18S rDNA 5′ end, and reverse primer 1137 (5′-GTGCCCTTCCGTCAAT), which began at reference bp 1475. The amplimer was designated GTSA.B1. Three diagnostic segments, bp 178 to 355, 705 to 926, and 1175 to 1379, located within GTSA.B1 and totaling 507 to 646 bp were then sequenced in both directions as previously described (35). However, sequencing of each segment in a single direction also provided reliable results and speeded up the diagnostic tests. Sequences were repeated three times. The sequencing primers used for single direction sequencing were 373 (5′-TCAGGCTCCCTCTCCGGAATC) for bp 178 to 355, 570C (5′-GTAATTCCAGCTCCAATAGC) for bp 705 to 926 (45), and 892C (5′-GTCAGAGGTGAAATTCTTGG) for bp 1175 to 1379. For bidirectional sequencing, we also used the PCR primers CRN5 and 1137 plus 892, the complement to 892C (32). Each diagnostic fragment included rDNA sequences that are highly variable within the genus Acanthamoeba (35).

Phylogenetic analysis.

The 18S rDNA sequence alignments were determined visually by using the programs ESEE (6) or CLUSTAL X (37) and a master alignment of 46 Acanthamoeba sequences including genotypes T1-T12 (www.biosci.ohio-state.edu/∼tbyers/byers.htm) plus a single sequence for Balamuthia mandrillaris (GenBank AF019071). Neighbor-joining distance trees were obtained using MEGA (23) with the Kimura two-parameter correction for multiple substitutions. Trees were rooted with the B. mandrillaris sequence.

GenBank accession numbers.

The ASA.S1 sequences of the Scottish isolates (WSKS) are designated AF343559 to AF343564 by GenBank, and the GTSA.B1 sequences of the South African isolates (SAW) are designated AF343801 to AF343836 with separate accession numbers for each of the three sequenced regions of the amplimer.

RESULTS

Genus specificity and amplification sensitivity of primer set JDP1-JDP2.

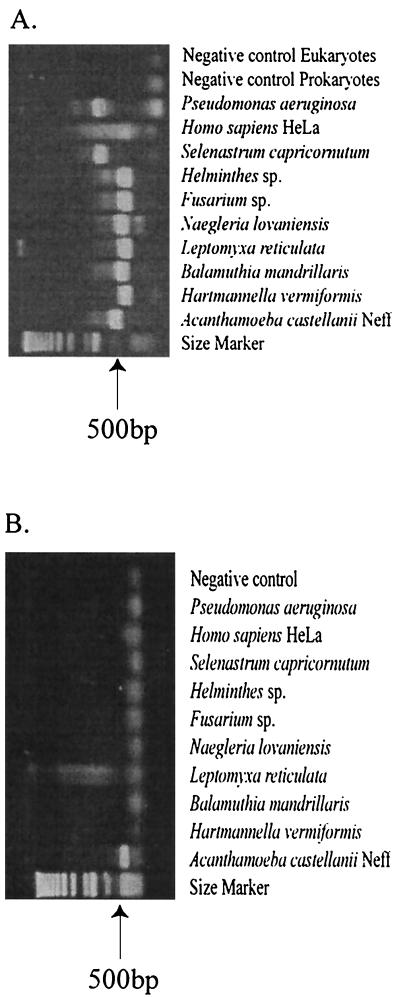

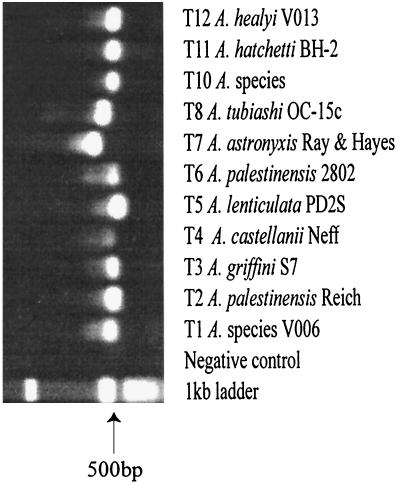

The genus specificity of PCR primer set JDP1-JDP2 was demonstrated by amplification of ASA.S1 from axenic cultures of trophozoites from each of the 12 Acanthamoeba 18S rDNA genotypes and by the lack of amplification from control bacteria, fungi, amoebae, and human cells listed in Table 1. Figure 1A illustrates the formation of a variably sized amplimer from all experimental and control organisms when PCR primer pair 570C-1262 (specific for eukaryotes) (44) and RA17–RA3-17 (specific for bacteria) (34) were used. In contrast, when the JDP1-JDP2 primer pair was used, an amplimer of ca. 423 to 551 bp was obtained from Acanthamoeba, but not from representatives of four other amoebic genera (Hartmannella, Naegleria, Leptomyxa, and Balamuthia), one algal genus (Selenastrum), two genera of fungi (Fusarium and Helminthes), one bacterial genus (Pseudomonas), or cultured human HeLa cells (Fig. 1B). Figure 2 illustrates that ASA.S1 was obtained from each of 11 genotypes of Acanthamoeba (T1 to T8 and T10 to T12). Although not illustrated, we have repeatedly shown that ASA.S1 also is obtained from the Comandon and DeFonbrune strain of A. comandoni which belongs to genotype T9.

TABLE 1.

Cell specimens used in testing the genus specificity of ASA.S1 amplification

| Species | Strain | Source and collection no. | 18S rDNA genotype |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acanthamoeba sp. | CDC 0981-V006 | T1 | |

| Acanthamoeba palestinensis | Reich | ATCC 30870 | T2 |

| Acanthamoeba griffini | S7 | ATCC 30731 | T3 |

| Acanthamoeba castellanii | Neff | ATCC 50373 | T4 |

| Acanthamoeba lenticulata | PD2S | ATCC 30841 | T5 |

| Acanthamoeba palestinensis | 2802 | ATCC 50708 | T6 |

| Acanthamoeba astronyxis | Ray & Hayes | ATCC 30137 | T7 |

| Acanthamoeba tubiashi | OC-15C | ATCC 30867 | T8 |

| Acanthamoeba comandoni | Comandon and DeFonbrune | ATCC 30135 | T9 |

| Acanthamoeba sp. | M. H. Awwad | T10 | |

| Acanthamoeba hatchetti | BH-2 | T. Sawyer | T11 |

| Acanthamoeba healyi | Visvesvara | CDC 1283-V013 | T12 |

| Hartmannella vermiformis | CCAP1501/3d | P. H. H. Weekers | |

| Balamuthia mandrillaris | CDC-V039 | ||

| Leptomyxa reticulata | F. L. Schuster | ||

| Naegleria lovaniensis | T. Endo | ||

| Fusarium species | P. E. Kolattukudy | ||

| Helminthes species | P. E. Kolattukudy | ||

| Selenastrum capricornutum | UTEX 1648 | ||

| Homo sapiens | HeLa | M. T. Muller | |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | W. C. Swoager |

FIG. 1.

Genus specificity of PCR amplification with JDP1 and JDP2. Direction of electrophoresis is left to right. (A) Amplification products from Acanthamoeba and control cells (Table 1) obtained using “universal” primer sets 570C and 1262 for eukaryotes (44) and RA17 and RA3-17 for Pseudomonas (33). (B) Generic-specific amplification product ASA.S1 obtained from Acanthamoeba using primer set JDP1 and JDP2. The negative controls in panels A and B lacked templates and their bands indicate positions of primer migration.

FIG. 2.

PCR amplification of ASA.S1 from 11 Acanthamoeba 18S rDNA genotypes using primers JDP1 and JDP2.

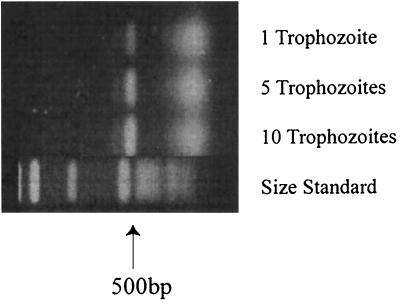

The extreme sensitivity of the assay was demonstrated in two ways. First, it was shown by amplification of ASA.S1 from as little as 1 pg of Acanthamoeba DNA (not illustrated), the approximate amount found in a single acanthamoeba (2, 4). Second, ASA.S1 also could be produced from a single trophozoite isolated with a micropipette (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Sensitivity of PCR amplification of ASA.S1 from isolated acanthamoebae. Amplification was obtained from 1 to 10 trophozoites of A. species CWT (genotype T4) isolated by K. Yagita.

Use of ASA.S1 to detect Acanthamoeba cysts in Scottish corneal scrapes.

PCR primer set JDP1 and JDP2 (Fig. 4A) was used to look for the presence of amoebae in 24 Scottish corneal scrape specimens (Table 2). The specimens tested here were from 17 patients (19 scrapings) with suspected AK and five patient controls (5 scrapings) with non-AK microbial keratitis or conjunctivitis. All specimens had been stored in sterile saline for 4 to 19 months prior to this analysis, and the amoebae appeared to be encysted at the time of testing, although the samples were dilute and an occasional trophozoite could not be ruled out. A single PCR amplimer of the expected size of ca. 460 to 470 bp for Acanthamoeba genotype T4 was obtained from specimens with scrape code numbers 1b, 2, 4, 5, 6, 8, 13, 19, and 23 (Table 2). A smaller amplimer between 423 and 460 bp was obtained for specimen 9, and several amplimers were obtained from specimen 17.

FIG. 4.

Variable regions, sequenced regions, and primers used for PCR and sequencing of ASA.S1 and GTSA.B1. (A) ASA.S1. The JDP1-JDP2 amplimer is represented by the line passing through the shaded box. Sequencing was unidirectional with primer 892C or bidirectional with 892C plus JDP2 in the directions indicated by the arrows. The shaded box represents the diagnostic sequence lying within the variable region of the amplimer. Reference base pairs are above the diagram. (B) Locations of eight regions with high interstrain sequence variation in GTSA.B1. (C) The three diagnostic regions sequenced within GTSA.B1. The locations and directions of the amplification primers CRN5 and 1137 and the sequencing primers 373, 570C, 892C, and 892 are indicated by arrows.

TABLE 2.

Detection of Acanthamoeba in Scottish corneal scrapes by PCR and comparison of results with previous findings (35) using detection by culture growth or FISH

| Clinical evaluation and scrape code no.a | Detection of amoebae by cultureb/FISHc/PCRd | 18S rDNA genotypee |

|---|---|---|

| Presumed AK | ||

| 1af | +/−/− | − |

| 1bf | +/+/+ | T3, T4, or T11 |

| 2 | +/+/+ | T3, T4, or T11 |

| 3ag | −/−/− | − |

| 3bg | −/−/− | − |

| 4 | +/+/+ | T3, T4, or T11 |

| 5 | +/+/+ | T3, T4, or T11 |

| 6 | +/+/+ | T3, T4, or T11 |

| 7 | −/−/− | − |

| 8 | +/+/+ | T3, T4, or T11 |

| 9 | +/+/+ | − |

| 10 | +/+/− | − |

| 12 | +/+/− | − |

| 13 | +/+/+ | − |

| 15 | −/−/− | − |

| 16 | −/−/− | − |

| 18 | +/+/− | − |

| 19 | +/+/+ | − |

| 23 | +/−/+ | − |

| Non-AK eye disease | ||

| 11 | −/−/− | − |

| 14 | −/−/− | − |

| 17 | +/−/+ | − |

| 21 | −/−/− | − |

| 22 | −/−/+ | − |

Specimens originally were fresh corneal scrapes (35).

+, culture growth previously observed at the Tennent Institute and/or The Ohio State University; 11 of 15 isolates were positive at both sites (35).

+, detection by FISH previously observed with acanthamoeba-specific probe (35).

+, ASA.S1-sized amplimer observed.

−, amplimer not observed or not sequenced.

Scrapes a and b were from the same eye on different days.

Scrapes a and b were from different eyes of the patient.

The PCR findings were compared with our previous report on culture growth and FISH analyses of the same specimens (36) (Table 2). ASA.S1 was obtained from 11 of 15 specimens (73%) that were culture positive and from one of nine specimens that were culture negative. Overall, the positive and negative PCR and culture results were in agreement for 79% (19 of 24) of the specimens. If sample 22, the single PCR-positive–culture-negative case, is included, the PCR results appear to have provided the appropriate clinical information for 83% (20 of 24) of the specimens. In addition, PCR-negative specimens 10, 12, and 18 were previously shown to be both culture positive and FISH positive (Table 2). Thus, combining PCR and FISH results detected amoebae in 93% (14 of 15) of the culture-positive specimens as well as in one specimen (specimen 22) that was both culture and FISH negative.

Use of bp 1271 to 1383 within ASA.S1 for genotype identification of the Scottish corneal scrapes.

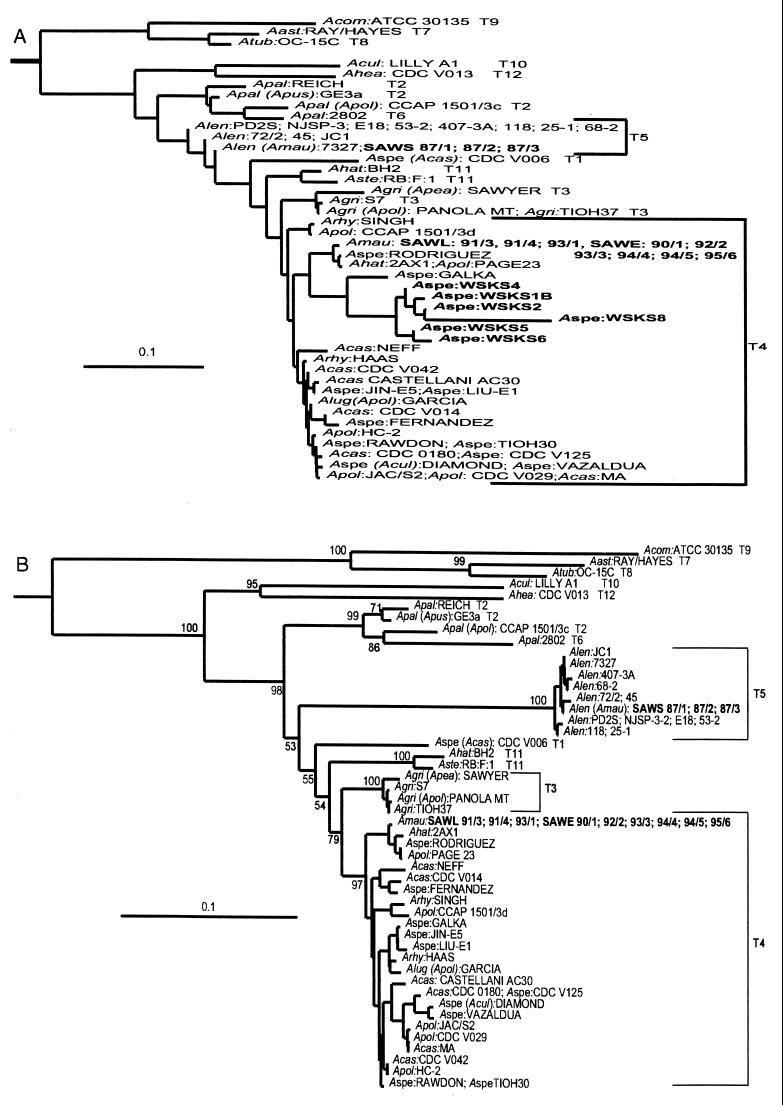

Stothard et al. (35) defined 12 18S rDNA genotypes based on phylogenetic reconstructions that included 1,846 alignable bases obtained from complete 18S rDNA sequences of 2,300 to 2,700 bp. To reduce the time and expense involved in accurately sequencing the entire gene, we searched for a subset of the ASA.S1 amplimer sequence that would support a phylogenetic reconstruction similar to that obtained by Stothard et al. (35). Visual inspection of the ASA.S1 segment in the master alignment suggested that the sequence between bp 1271 and 1383 (Fig. 4A), which encoded the 5′ side of 18S rRNA stem 29 and most of stem 29-1 (35), might be suitable for this purpose. Thus, this region was used in a phylogenetic reconstruction (Fig. 5A) that included homologous regions from sequences in the master alignment plus the six Scottish scrape specimens plus 12 South African isolates to be considered below. The tree produced was based on 46 sequences that are unique in this region and which represent 71 strains. The analysis suggests that the Scottish scrape specimens (WSKS) are genotype T4. In analyses based on complete gene sequences, however, this genotype forms a clade with T3 and T11 (35). In the absence of a test for significance in the present analysis, T4 cannot reliably be distinguished from the other two genotypes. Thus, we assign all the specimens to the T3-T4-T11 clade. Further analysis of the Scottish specimens was impossible due to sample depletion. Thus, we utilized the South African specimens for identification of sequences that could be the basis for a more reliable genotype-specific sequence analysis.

FIG. 5.

Neighbor-joining distance trees based on partial 18S rDNA sequences. The trees were obtained as described in Materials and Methods. (A) Tree based on reference bp 1271 to 1377 within amplimer ASA.S1. Species abbreviations: Aast, A. astronyxis; Acas, A. castellanii; Acom, A. comandoni; Acul, A. culbertsoni; Agri, A. griffini; Ahat, A. hatchetti; Ahea, A. healyi; Alen, A. lenticulata; Alug, A. lugdunensis; Amau, A. mauritaniensis; Apal, A. palestinensis; Apea, A. pearcei; Apol, A. polyphaga; Apus, A. pustulosa; Arhy, A. rhysodes; Aspe, A. species; Aste, A. stevensoni; Atub; A. tubiashi. See Stothard et al. (35) for culture sources and GenBank accession numbers. Strains from the Western Scotland keratitis survey (WSKS) and the South African specimens (SAW) examined in this study are in boldface. The scale bar represents the corrected number of nucleotide substitutions per base using the Kimura method. (B) Tree based on bp 178 to 355, 705 to 926, and 1175 to 1379 in GTSA.B1. South African strains are in boldface. Bootstrap values are based on 500 replicas and are placed at the nodes to which they apply. Values of <50 and for closely related strains are omitted. The scale bar is the same as for panel A.

Use of GTSA.B1 bp 178 to 355, 705 to 926, and 1175 to 1379 to reliably distinguish all genotypes.

Although ASA.S1 was clearly specific for the genus, additional sequence variation was required to provide enough phylogenetically significant information for a test of the significance of branching patterns that differentiate the 12 18S rDNA genotypes. Thus, we searched for another amplimer that both would be specific for the genus and could be used to differentiate all known genotypes. We wanted an amplimer containing sequences that would support a phylogenetic reconstruction comparable to that obtained for complete gene sequences by Stothard et al. (35). We began by using Acanthamoeba 18S rDNA sequences for amplimers thought by other investigators to be specific for the genus (15, 19, 25, 27, 40). These amplimers, however, all were unsuitable for achieving at least one of our three objectives, i.e., (i) they were not likely to be sufficiently specific for Acanthamoeba, (ii) they could not be obtained from all 12 genotypes, or (iii) the amplimer sequences were insufficient to differentiate the most closely related genotypes. Unfortunately, we also failed to identify a single PCR primer pair that produced an amplimer suitable for all three purposes. Thus, ASA.S1 was used to satisfy the first two objectives because it could do this better than any of the amplimers used by other laboratories. The third requirement was satisfied using sequences of three diagnostic regions within the larger amplimer GTSA.B1. Because this amplimer could be obtained from all eukaryotes, we used axenic amoeba cultures to study whether sequences of the diagnostic regions could be used to differentiate among genotypes. GTSA.B1 ranged from 1,400 to 1,700 bp depending on the genotype and was even larger if an intron were present in the amplified region, as found in some strains of A. griffini (12, 24). Sequence alignments detect eight segments of variable sequence that occur within this amplimer (Fig. 4B). Three regions of the amplimer, reference bp 178 to 355, 705 to 926, and 1175 to 1379 (Fig. 4C), which include seven of the variable regions, were selected for a multilocus sequencing analysis. The first region includes a large portion of the amplimer used by Kim et al. (19). The second region covers a sequence that hasn't been used previously for sequencing studies but has been included in an amplimer used by Kong and Chung for riboprinting studies (21). The third region includes the sequence used above in ASA.S1 and also is found within the riboprinting amplimer used by Kong and Chung. GTSA.B1 was obtained with two PCR primers, and sequences of the three diagnostic regions could be obtained with three to six sequencing primers depending on whether sequencing was unidirectional or bidirectional. This contrasted with up to 20 primers we have used in the past for manual sequencing of the complete gene. This is the first subgenic fragment found to have sufficient information for differentiating all of the genotypes reliably.

Genotype identification of South African eye and sewage isolates using GTSA.B1.

The South African isolates, all previously identified as A. mauritaniensis (www.atcc/org), appeared to separate into two different groups in the analysis based on ASA.S1 sequences. One group consisted of six isolates from the eyes of patients with AK (SAWE, ATCC 50676 to 50681) plus three isolates from the contact lens or lens cases of AK patients (SAWL, ATCC 50682 to 50684). The second group included three isolates from sewage sludge (SAWS, ATCC 50685 to 50687) (29). This relationship was tested more rigorously with an analysis that permitted a test of the significance of the topology. A total of 48 unique sequences for the three combined diagnostic regions of GTSA.B1 were extracted from the master alignment of complete sequences. They then were combined in a neighbor-joining phylogenetic reconstruction with homologous sequences obtained here from the 12 South African specimens. The tree produced included 60 sequences representing 64 Acanthamoeba strains. The topology (Fig. 5B) was very similar to that obtained for the sequence from ASA.S1 (Fig. 5A), but in this case terminal genotypes could be distinguished by high bootstrap values or distance of separation. For example, terminal bootstrap values of 97% for T4, which includes the AK-related isolates, and 100% for T5, which includes the sewage isolates, were obtained. The tree topology was similar to that previously obtained by Stothard et al. using complete 18S rDNA sequences (35) although that study did not include the South African isolates. The African AK-related isolates associated here with genotype T4 strains, and the sewage isolates associated with strains having the very distinctive T5 genotype.

DISCUSSION

Genus specificity of PCR.

The first objective in the present study was the design of primer pairs capable of amplifying a genus-specific amplimer from representatives of all described Acanthamoeba 18S rDNA genotypes. The use of PCR amplimers for the genus-specific detection of Acanthamoeba was attempted first by Vodkin et al. (40). These authors used primer pair ACARNA 1383-1655, which amplified bp 1383 to 1655, to demonstrate that PCR products could be obtained from a number of strains, from as few as one amoeba, and from either formalin-fixed or fresh material. Lehmann et al. (25) subsequently demonstrated the usefulness of this primer pair for the detection of amoebae in AK. These authors also described a second 18S rDNA primer pair, PIGP.2379for-2632rev, which amplified bp 1835 to 2079 and was used to confirm the presence of Acanthamoeba in their clinical study. A nearly identical amplimer, just 16 bp shorter, was used in another clinical study (27). A third potential genus-specific primer pair amplifying bp 66 to 585 also was useful for identification of eye isolates (19).

Now that substantial amounts of 18S rDNA sequence are available for more than 80 isolates of Acanthamoeba (10, 35, 42; and the isolates described here), they can be used with sequences for other amoeba genera to reevaluate the probable genus specificity of various PCR primer sets. We have used a master alignment of complete 18S rDNA sequences to predict that amplification with primer pairs ACARNA 1383-1655 and P1GP 2379-2632 would be successful not only with all rDNA genotypes of Acanthamoeba but also with closely related amoebae from the genera Balamuthia (GenBank AF019071) and Hartmannella (44). Thus, amplimers produced with these two primer pairs would not be specific for Acanthamoeba. The primer set 66-585 (19) would be specific for Acanthamoeba but only should amplify from the genotypes of morphological groups 2 and 3 (T1 to T6 and T10 to T12). Thus, the larger acanthamoebae of genotypes T7, T8, and T9 of morphological group 1 would not be detected.

In the work described here, a database of 18S rDNA sequences was used to design a genus-specific primer set that would amplify a product from all Acanthamoeba 18S rDNA genotypes and would not amplify from other closely related genera of amoebae or from distant control organisms including humans. This objective was achieved with the primer set JDP1-JDP2. The actual testing of amplification from representatives of each genotype (Fig. 2) confirmed the predictions based on sequence analysis and demonstrated that the predicted amplimer was obtained in each case.

Sensitivity of PCR with JDP1 and JDP2.

We, like Vodkin et al. (40), were able to amplify a product from a single trophozoite. Here, amoebae were isolated with a micropipette to avoid uncertainties associated with cell dilutions. The observation was supported also by PCR of DNA dilutions. The average content of uninucleate trophozoites is 1 to 2 pg (2, 4), and ASA.S1 could be obtained from 1 pg. The sensitivity was demonstrated further in sample 22, in which PCR detected amoebae even though the specimen was culture-negative at both TIO and OSU (Table 2). However, we failed to obtain amplimers from culture- and FISH-positive specimens 10, 12, and 18 and from culture-positive but FISH-negative specimen 1a. The reasons for these failures are unknown. We do know that cell clones can be obtained from single trophozoites or cysts. Likewise, we have shown here that a single trophozoite is sufficient for PCR. Although the use of PCR with cysts hasn't been examined carefully by anyone to our knowledge, we have never been able to obtain amplimers from mature cysts. Thus, one possible explanation for the results in the present study is that success of PCR depends on the presence in the samples of one or more trophozoites or immature cysts and that only mature cysts were present in the culture-positive specimens where PCR failed.

Identification of Acanthamoeba 18S rDNA genotypes.

For many purposes, it is sufficient to identify amoebae at the generic level. In the case of Acanthamoeba, identification of species has been problematic. The subgeneric classification used here is based on interstrain variations in 18S rDNA sequences. The relationships between the rDNA genotypes and individual morphological species is still in question, although there is a relatively consistent correlation between the three traditional morphological groups of strains and clusters of genotypes (35). In some cases, however, there is a good correlation between a morphological species and a particular genotype. The strong correlation between genotype T5 and A. lenticulata in past studies (32, 35) is a good example of this. Thus, it is our basis for suggesting a change in the species name of the sewer sludge isolates from A. mauritaniensis to A. lenticulata. The 12 isolates of A. lenticulata examined prior to this study were classified by experts based on criteria other than DNA sequences (9, 29). With the addition of the South African amoebae, we now have sequence data for 15 isolates of genotype T5. The 18S rDNA sequence, exclusive of introns, varies relatively little among these isolates. In addition, the complete 18S rDNA of the A. mauritaniensis ATCC 50253, which is derived from the type strain, has been sequenced by R. J. Gast (unpublished data) and ourselves. This isolate clearly has a T4 rather than a T5 genotype.

At present, ASA.S1 is the best choice for specific detection of acanthamoebae because it is highly selective for the genus and can be obtained from all known 18S rDNA genotypes. This should make it particularly useful for environmental samples which might include any of the acanthamoeba genotypes. The sequence of this amplimer can be used to distinguish most of the genotypes but cannot reliably distinguish the closely related members of the T3-T4-T11 clade. This clade is of special interest because several studies indicate that T4 amoebae are the predominant agents of Acanthamoeba keratitis (35, 41, 42). Our use of GTSA.B1 here has demonstrated that the South African eye and contact lens isolates also belong to this genotype. Thus, the combined results of Stothard et al. (35), Walochnik et al. (41, 42), and the present study now have shown that 38 of 40 Acanthamoeba isolates from the eyes of AK patients belong to this genotype. The two published exceptions are one T3 isolate (24) and one T6 isolate (41, 42). As shown previously, a T4-specific FISH probe can be used to identify amoebae from this genotype (36). We have delayed the design of similar probes for the other genotypes, however, until more sequences are available and the sequence diversity within each genotype is clearer. Thus, at present, reliable differentiation of these most closely related genotypes can be obtained either by sequencing the complete 18S rRNA gene of ca. 2,300 to 3,000 bp (35) or by using the multilocus sequencing of GTSA.B1 which only involves ca. 500 to 650 bp. The former approach is the most likely choice where automated sequencing is available, but the latter is much more practical in the many laboratories where manual sequencing is used.

Infections in immunologically compromised individuals may involve a wider range of rDNA genotypes of Acanthamoeba, as well as isolates of the genus Balamuthia (26, 39). Although only four complete 18S rDNA sequences have been reported from immunodeficient patients, they represent genotypes T1, T4, and T12 (35) and possibly will include others. For example, although the genotype T5 A. lenticulata has not yet been associated with human disease, the sewage sludge isolates used here were shown to be cytopathogenic to human tissue culture cells (29). Thus, genus-specific PCR of samples from infections in patients with compromised immune responses should use primer sets that have been shown to be useful in detecting all known 18S rDNA genotypes.

The relative values of sequencing and other methods for identification of genotypes.

Rapid advances in the accuracy and rapidity of automated DNA sequencing technology and the increasing availability of automated sequencing facilities around the world make the use of PCR and DNA sequencing for identification of microbial isolates increasingly attractive. In our experience, the ability to culture Acanthamoeba from specimens is the most successful assay for these organisms. However, the formation of a colony can take a week or more. Thus, a sensitive method, such as PCR with primers JDP1 and JDP2, that is able to detect amoebae of all Acanthamoeba genotypes in 1 to 2 days without the need for cell multiplication, is especially useful for clinical applications. As shown here, success in detection within the same time period can be greater than 90% if PCR and sequencing are used in combination with genus-specific FISH.

Although we believe that sequencing of DNA is the most reliable indicator of strain relationships, the recent use of riboprinting, that is, the analysis of restriction fragment length polymorphisms of complete 18S rRNA genes, is promising. With some minor exceptions, we conclude that a recent phylogenetic tree constructed by Chung et al. (8) based on riboprints of reference strains of Acanthamoeba is consistent with the rDNA tree of Stothard et al. (35). As noted by Chung et al., however, inconsistencies do arise if introns are present in the rDNA, as is the case for the A. griffini isolate used in their study (8, 12, 24), as well as for some strains of A. lenticulata (32). The riboprinting study included data for four species, A. divionensis, A. paradivionensis, A. triangularis, and A. quina, for which 18S rDNA sequences had not yet been reported. Based on the distance analysis used for the riboprinting study, these species all appear to cluster with isolates previously identified (35) as genotypes T4 or T11. We now have determined the sequence for A. triangularis SH621 (GenBank AF346662) and confirm that it does have a T4 genotype.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The molecular biology in this report was funded by Public Health Service grant EY09073 awarded to P.A.F. and T.J.B. by the National Eye Institute. M.B.M. received support from the South African Medical Research Council and the Medical Faculty Research Endowment Fund of The University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg.

We thank Kenji Yagita, Institute of Parasitology, Japanese National Institutes of Health, Tokyo, for his skillful isolation of single amoebae by micropipette while visiting in the Ohio State University laboratory.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alves J M P, Gusmao C X, Teixeira M M G, Freitas D, Foronda A S, Affonso H T. Random amplified polymorphic DNA profiles as a tool for the characterization of Brazilian keratitis isolates of the genus Acanthamoeba. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2000;33:19–26. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2000000100003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Byers T J. Molecular biology of DNA in Acanthamoeba, Amoeba, Entamoeba and Naegleria. Int Rev Cytol. 1986;99:311–334. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)61430-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Byers T J, Hugo E R, Stewart V J. Genes of Acanthamoeba: DNA, RNA and protein sequences (a review) J Protozool. 1990;37:17S–25S. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1990.tb01141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Byers T J, Rudick V L, Rudick M J. Cell size, macromolecule composition, nuclear number, oxygen consumption and cyst formation during two growth phases in unagitated cultures of Acanthamoeba castellanii. J Protozool. 1969;16:693–699. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1969.tb02329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Byers T J, Akins R A, Maynard B J, Lefken R A, Martin S M. Rapid growth of Acanthamoeba in defined media; induction of encystment by glucose-acetate starvation. J Protozool. 1980;27:216–219. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1980.tb04684.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cabot E L, Beckenbach A T. Simultaneous editing of multiple nucleic acid and protein sequences with ESEE. Comput Appl Biosci. 1989;5:233–234. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/5.3.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chung D-I, Kong H-H, Yu H-S, Oh Y-M, Yee S-T, Lim Y-J. Biochemical and molecular characterization of a strain KA/S2 of Acanthamoeba castellanii isolated from Korean soil. Korean J Parasitol. 1996;34:79–85. doi: 10.3347/kjp.1996.34.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chung D-I, Yu H-S, Hwang M-Y, Kim T-H, Kim T-O, Yun H-C, Kong H-H. Subgenus classification of Acanthamoeba by riboprinting. Korean J Parasitol. 1998;36:69–80. doi: 10.3347/kjp.1998.36.2.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Jonckheere J F, Michel R. Species identification and virulence of Acanthamoeba strains from human nasal mucosa. Parasitol Res. 1988;74:314–316. doi: 10.1007/BF00539451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dykova L, Lom J, Schroeder-Diedrich J M, Booton G C, Byers T J. Acanthamoeba strains isolated from organs of freshwater fishes. J Parasitol. 1999;85:1106–1113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gast R J, Byers T J. Genus- and subgeneric-specific oligonucleotide probes for Acanthamoeba. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1995;71:255–260. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(94)00049-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gast R J, Fuerst P A, Byers T J. Discovery of group 1 introns in the nuclear small subunit ribosomal RNA genes of Acanthamoeba. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:592–596. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.4.592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gautom R K, Lory S, Seyedirashti S, Bergeron D L, Fritsche T R. Mitochondrial DNA fingerprinting of Acanthamoeba spp. isolated from clinical and environmental sources. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1070–1073. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.4.1070-1073.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gunderson J H, Sogin M L. Length variation in eukaryotic rRNAs: small-subunit rRNAs from the protists Acanthamoeba castellanii and Euglena gracilis. Gene. 1986;44:63–70. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(86)90043-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Howe D K, Vodkin M H, Novak R J, Visvesvara G, McLaughlin G L. Identification of two genetic markers that distinguish pathogenic and nonpathogenic strains of Acanthamoeba. Parasitol Res. 1997;83:345–348. doi: 10.1007/s004360050259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hugo E R, Stewart V J, Gast R J, Byers T J. Purification of amoeba mtDNA using the UNSET procedure. In: Soldo A T, Lee J J, editors. Protocols in protozoology. Lawrence, Kans: Allen Press; 1992. p. D7.1. [Google Scholar]

- 17.John D T. Opportunistically pathogenic free-living amebae. In: Kreier J P, Baker J R, editors. Parasitic protozoa. 2nd ed. Vol. 3. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press, Inc.; 1993. pp. 143–246. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kilvington S, Beeching J R, White D G. Differentiation of Acanthamoeba strains from infected corneas and the environment by using restriction endonuclease digestion of whole-cell DNA. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:310–314. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.2.310-314.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim K S, Mathers W D, Alexandrakis G, Sutphin J E, Wiles C D. Polymerase chain reaction for Acanthamoeba keratitis, primer selection and inhibitory factors. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1997;38(Pt. 2):5016. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim Y H, Ock M-S, Yun H-C, Hwang M Y, Yu H-S, Kong H-H, Chung D-I. Close relatedness of Acanthamoeba pustulosa with Acanthamoeba palestinensis based on isozyme profiles and rDNA PCR--RFLP patterns. Korean J Parasitol. 1996;34:259–266. doi: 10.3347/kjp.1996.34.4.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kong H-H, Chung D-I. PCR and RFLP variation of conserved region of small subunit ribosomal DNA among Acanthamoeba isolates assigned to either A. castellanii or A. polyphaga. Korean J Parasitol. 1996;34:127–134. doi: 10.3347/kjp.1996.34.2.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kong H-H, Park J-H, Chung D-I. Interstrain polymorphisms of isoenzyme profiles and mitochondrial DNA fingerprints among seven strains assigned to Acanthamoeba polyphaga. Korean J Parasitol. 1995;33:331–340. doi: 10.3347/kjp.1995.33.4.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumar S, Tamura K, Nei M. Molecular evolutionary genetic analysis, version 1.02. The Pennsylvania State University, State College; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ledee D R, Hay J, Byers T J, Seal D V, Kirkness C M. Acanthamoeba griffini: molecular characterization of a new corneal pathogen. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1996;37:544–550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lehmann M O, Green S M, Morlet N, Keys M F, Matheson M M, Dart J K G, McGill J I, Watt P J. Polymerase chain reaction analysis of corneal epithelial and tear samples in the diagnosis of Acanthamoeba keratitis. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1998;39:1261–1265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martinez A J, Visvesvara G S. Free-living amphizoic and opportunistic amebas. Brain Pathol. 1997;7:583–598. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1997.tb01076.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mathers W D, Nelson S E, Lane J L, Wilson M E, Allen R C, Folberg R. Confirmation of confocal microscopy diagnosis of Acanthamoeba keratitis using polymerase chain reaction analysis. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000;118:178–183. doi: 10.1001/archopht.118.2.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Molet B, Ermolieff-Braun G. Description d'une Amibe d'eau douce: Acanthamoeba lenticulata, sp. nov. (Amoebida) Protistologica. 1976;12:571–576. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Niszl I A, Veale R B, Markus M B. Cytopathogenicity of clinical and environmental Acanthamoeba isolates for two mammalian cell lines. J Parasitol. 1998;84:961–967. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pussard M, Pons R. Morphologie de la paroi kystique et taxonomie du genre Acanthamoeba (Protozoa, Amoebida) Protistologica. 1977;8:557–598. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rychlik W, Rhoads R E. A computer program for choosing optimal oligonucleotides for filter hybridization, sequencing and in vitro amplification of DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:8513–8551. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.21.8543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schroeder-Diedrich J M, Fuerst P A, Byers T J. Group-I introns with unusual sequences occur at three sites in nuclear 18S rRNA genes of Acanthamoeba lenticulata. Curr Genet. 1998;34:71–78. doi: 10.1007/s002940050368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seal D V, Kirkness C M, Bennett H G B, Peterson M The Keratitis Study Group. Population-based cohort study of microbial keratitis in Scotland: incidence and features. Contact Lens Ant Eye. 1999;22:49–57. doi: 10.1016/s1367-0484(99)80003-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stothard D R, Fuerst P A. Evolutionary analysis of the spotted-fever and typhus groups of Rickettsia using 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequences. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1995;18:52–61. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stothard D R, Schroeder-Diedrich J M, Awwad M H, Gast R J, Ledee D R, Rodriguez-Zaragoza S, Dean C L, Fuerst P A, Byers T J. The evolutionary history of the genus Acanthamoeba and the identification of eight new 18S rRNA gene sequence types. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 1998;45:45–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1998.tb05068.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stothard D R, Hay J, Schroeder-Diedrich J M, Seal D V, Byers T J. Fluorescent oligonucleotide probes for clinical and environmental detection of Acanthamoeba and the T4 18S rRNA gene sequence type. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:2687–2693. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.8.2687-2693.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thompson J D, Gibson T J, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins D G. The CLUSTAL X Windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;24:4876–4882. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Visvesvara G S. Classification of Acanthamoeba. Rev Infect Dis. 1991;13(S5):S369–S372. doi: 10.1093/clind/13.supplement_5.s369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Visvesvara G S, Schuster F L, Martinez A J. Balamuthia mandrillaris, N. G., N. Sp., agent of amebic meningoencephalitis in humans and other animals. J Eukaryot Micro. 1993;40:504–514. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1993.tb04943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vodkin M H, Howe D K, Visvesvara G S, McLaughlin G L. Identification of Acanthamoeba at the generic and specific levels using the polymerase chain reaction. J Protozool. 1992;39:378–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1992.tb01467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Walochnik J, Obwaller A, Aspöck H. Correlations between morphological, molecular biological, and physiological characteristics in clinical and nonclinical isolates of Acanthamoeba spp. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:4408–4413. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.10.4408-4413.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Walochnik J, Haller-Schober E M, Kölli H, Picher O, Obwaller A, Aspöck H. Discrimination between clinically relevant and nonrelevant Acanthamoeba strains isolated from contact lens-wearing keratitis patients in Austria. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:3932–3936. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.11.3932-3936.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Walsh P S, Metzger D A, Higuchi R. Chelex 100 as a medium for simple extraction of DNA for PCR-based typing from forensic material. BioTechniques. 1991;10:506–513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weekers P H H, Gast R J, Fuerst P A, Byers T J. Sequence variation in small-subunit ribosomal RNAs of Hartmannella vermiformis and the phylogenetic implications. Mol Biol Evol. 1994;11:684–690. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yagita K, Endo T. Restriction enzyme analysis of mitochondrial DNA of Acanthamoeba strains in Japan. J Protozool. 1990;37:570–575. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1990.tb01267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yu H-S, Hwang M-Y, Kim T-O, Yun H-C, Kim T-H, Kong H-Y, Chung D-I. Phylogenetic relationships among Acanthamoeba spp. based on PCR-RFLP analyses of mitochondrial small subunit rRNA gene. Korean J Parasitol. 1999;37:181–186. doi: 10.3347/kjp.1999.37.3.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]