Abstract

Background

External control (EC) data from completed clinical trials and electronic health records can be valuable for the design and analysis of future clinical trials. We discuss the use of EC data for early stopping decisions in randomized clinical trials (RCTs).

Methods

We specify interim analyses (IAs) approaches for RCTs, which allow investigators to integrate external data into early futility stopping decisions. IAs utilize predictions based on early data from the RCT, possibly combined with external data. These predictions at IAs express the probability that the trial will generate significant evidence of positive treatment effects. The trial is discontinued if this predictive probability becomes smaller than a prespecified threshold. We quantify efficiency gains and risks associated with the integration of external data into interim decisions. We then analyze a collection of glioblastoma (GBM) data sets, to investigate if the balance of efficiency gains and risks justify the integration of external data into the IAs of future GBM RCTs.

Results

Our analyses illustrate the importance of accounting for potential differences between the distributions of prognostic variables in the RCT and in the external data to effectively leverage external data for interim decisions. Using GBM data sets, we estimate that the integration of external data increases the probability of early stopping of ineffective experimental treatments by up to 25% compared to IAs that do not leverage external data. Additionally, we observe a reduction of the probability of early discontinuation for effective experimental treatments, which improves the RCT power.

Conclusion

Leveraging external data for IAs in RCTs can support early stopping decisions and reduce the number of enrolled patients when the experimental treatment is ineffective.

Keywords: external control data, interim futility analysis, newly diagnosed glioblastoma, predictions, study design

Key Point.

• Leveraging external data for interim analyses (IAs) in randomized clinical trials (RCTs) can (i) reduce the number of enrollments to ineffective experimental treatment, (ii) increase the power, and (iii) maintain a rigorous control of the type I error rate.

Importance of the Study.

External control (EC) data from prior clinical trials and electronic health records have the potential to accelerate drug-development processes. We show that in glioblastoma (GBM) the use of EC data for futility interim analysis can shorten the average study duration and increase the likelihood of early termination of studies which test ineffective experimental treatment, with rigorous control of the type I error rate.

Only a fraction of treatments tested in early stage clinical studies proceed successfully through clinical development and gains regulatory approval.1,2 There are clear advantages in the adoption of trial designs that rapidly discontinue the evaluation of ineffective or toxic treatments, reducing the number of enrolled patients.

External data from prior trials and from clinical databases can be valuable to improve the design, conduct, and analysis of clinical studies.3–5 External data may be used in the analysis of single-arm clinical studies, to form an external control arm in the evaluation of experimental therapeutics.6–11 External information can also be used to select study parameters, such as the sample size of a new study, or to identify patient subpopulations that benefit from experimental treatments. In this manuscript we describe and evaluate the use of external control (EC) data representative of the standard of care (SOC), during the clinical trial, for interim analyses (IAs). We focus on early futility decisions in randomized clinical trials (RCTs).

Interim decisions can utilize EC data when suitable external data sets are available. We specify IAs that leverage EC data, and we evaluate if the use of EC data improves early discontinuation decisions. Our interim decisions rely on Bayesian predictive computations,12–15 which, at each IA, indicate the probability of a significant result at the end of the study (eg, the probability of a P-value < .05 at final analyses). The trial is stopped early for futility if this predictive probability falls below a prespecified threshold. These futility IAs do not increase the type I error rate above the nominal α level, irrespective of potential differences between the RCT and the EC populations. Indeed, the final efficacy analyses, at completion of the trial, use only data from the RCT.

We compare IAs that leverage EC data with IAs based only on internal data from the ongoing RCT. These comparisons include (i) a simulation study and (ii) the analysis of a collection of glioblastoma (GBM) data sets using a model-free validation algorithm. The algorithm provides estimates of trial designs’ operating characteristics (power, expected number of enrollments, etc.), accounting for potential differences between the distributions of pretreatment patient profiles in the enrolled RCT population and in the EC group. Our study illustrates the operating characteristics of futility IAs that leverage EC data, with comparisons to IAs that do not use EC data. We discuss scenarios representative of potential discrepancies between the distributions of the patient pretreatment profiles in the RCT and the EC population.

Although the concept of leveraging EC data to improve IAs is applicable in many settings, we estimate merits and risks in GBM, where the majority of phase II and III trials have failed during the last two decades.16

Methods

RCT Design

We consider a RCT with IAs that can stop the study for futility. If the trial is not stopped for futility, then the final analyses, after the enrollment of N patients (the maximum sample size), do not utilize EC data. The null hypothesis H0: TE ≤ 0, where TE quantifies the treatment effect of the experimental treatment, is rejected if a standard data summary Z exceeds a threshold tα which controls the type I error rate at a prespecified α level. With binary outcomes the TE will be the difference between the response probabilities of the experimental and control arms, while the summary Z will be the two-sample z-statistics.17 The EC data are not used in the outlined hypothesis-testing procedure.

Interim Analyses

The RCT can be terminated early at IAs for futility. We use a Bayesian model for the unknown distribution Pr(Y, X, A) (Y: outcome; X: patient pretreatment characteristics; A: treatment, SOC A = 0, or experimental A = 1). At each IA the model predicts if at completion of the study there will be significant evidence of a positive treatment effect (ie, Z > tα). The study is stopped if the predictive probability (Pr) of significant effects is smaller than a prespecified threshold (b ≥ 0),

| (1) |

We consider three approaches to compute the probability (expression 1) of a significant result.

(i) The first one uses only early internal data (IA–ID) from the ongoing RCT. The other two approaches leverage an EC data set that consists of individual pretreatment profiles X and outcomes Y of patients treated with the SOC.

(ii) In particular, the IA–EC method (IA with EC data), augments the internal outcome data Y of patients randomized to the control arm (A = 0) with EC outcome data. This procedure ignores potential differences between the distributions of pretreatment prognostic characteristics of the two SOC groups (RCT and EC). In our analyses the IA–ID and IA–EC predictions (expression 1) are based on the standard Beta-Binomial model,18 and do not involve pretreatment characteristics X.

(iii) The third method, IA–EC–X (IA with EC data and adjustments for pretreatment variables X), combines the RCT data (Y, X, A) and the EC data (Y, X, A = 0) with a Bayesian logistic regression model.18 This model estimates the conditional outcome distributions Pr(Y|X, A) for the control (A = 0) and the experimental (A = 1) arms. IA–EC–X assumes that the conditional outcome distributions Pr(Y|X, A = 0) in the internal and external populations are identical. Predictions (expression 1) are based on samples of the logistic model parameters from the posterior distribution and standard Bayesian imputation methods.

We compare the IA–EC and IA–EC–X procedures to illustrate the importance of accounting for pretreatment variables which can have different distributions in the RCT and EC populations. Statistical details of the IA procedures are provided in the Supplementary Material.

We evaluate IAs (IA–ID, IA–EC, and IA–EC–X) using model-based and model-free validation procedures.

Model-based evaluation

We generate clinical trials using simulation scenarios (Table 1) which include: (a) distributions of patient pretreatment variables in the RCT and in the EC, and (b) response probabilities to the experimental treatment and the SOC conditional on pretreatment variables. We include scenarios where (i) the distribution of pretreatment characteristics is different in the internal and external populations (scenarios 3–7), and (ii) only partial information on the patient profiles is available. For example, in scenarios 5–7 (Table 1) only two out of three pretreatment prognostic variables are available in the internal and external data for IAs.

Table 1.

Simulation Scenarios

| Scenarios | Distribution of Pretreatment Variables in the EC | Effects (log-OR) of Pretreatment Variables | Treatment Effects (log-OR γ A) | Response Rates P (Y =1 | A = 0 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (a)Measured | (b)Unmeasured | ||||||||||||

| Pec (X1 = 1) | Pec (X2 = 1) | Pec (X3 = A) | Pec (X3 = B) | β 1 | β 2 | β 3, B | β 3, C | TE = 0 | TE < 0 | TE > 0 | EC | IC | |

| 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1/3 | 1/3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | −0.2 | 0.85 | 0.50 | 0.5 |

| 2 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1/3 | 1/3 | 0.6 | −0.6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | −0.2 | 0.85 | 0.50 | 0.5 |

| 3 | 0.2 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.6 | −0.6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | −0.2 | 0.85 | 0.41 | 0.5 |

| 4 | 0.8 | 0.2 | 1/3 | 1/3 | 0.6 | −0.6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | −0.2 | 0.85 | 0.59 | 0.5 |

| 5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1/3 | 1/3 | 0.6 | −0.6 | −0.6 | 0.6 | 0 | −0.2 | 0.85 | 0.46 | 0.5 |

| 6 | 0.2 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.6 | −0.6 | −0.6 | 0.6 | 0 | −0.2 | 0.85 | 0.38 | 0.5 |

| 7 | 0.8 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.6 | −0.6 | −0.6 | 0.6 | 0 | −0.2 | 0.85 | 0.62 | 0.5 |

Abbreviations: IA, interim analysis; OR, odds ratio; RCT, randomized clinical trial; SOC, standard of care. We consider three pretreatment characteristics X = (X1, X2, X3); two binary variables X1, X2 ∈ {0, 1}, and a categorical variable X3 ∈ {A, B, C}. X3 is not available during the RCT and in the EC data. This variable is not used for IAs (unmeasured). Columns 2–5 provide, for the EC population, the distribution of all pretreatment variables, which have been generated independent of each other. Pretreatment variables of patients enrolled in the RCT were generated according to for variables i = 1, 2, and for v = A, B, and C. For the RCT we assume an enrollment rate of 5 patients per month. Patient outcomes (internal and external) were generated from a logistic model , γ 0 = 0 for the SOC. Columns 6–9 show the effects β i of pretreatment variables Xi, which are identical in the internal and external populations. Columns 10–12 indicate the treatment effects (expressed by log-ORs, γ 1) when the experimental arm has a positive, negative, or no treatment effects (TE > 0, TE < 0, TE = 0). The last two columns show the marginal response probability for the external (EC) and internal control (IC) populations.

Model-free evaluation algorithm

We use five GBM studies, a phase III study19 (NCT00943826, 460 patients), two phase II20,21 (PMID: 22120301, 16 patients; NCT00441142, 29 patients), and two real-world data sets (378 and 305 patients) from the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (DFCI) and the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). In the validation analysis we used individual-level data from patients treated with the SOC, temozolomide and radiation therapy (TMZ+RT).22 Pretreatment profiles X include age, sex, Karnofsky performance status, MGMT methylation status, and extent of tumor resection23–25 (see Supplementary Table S4). An institutional review board approved the project.

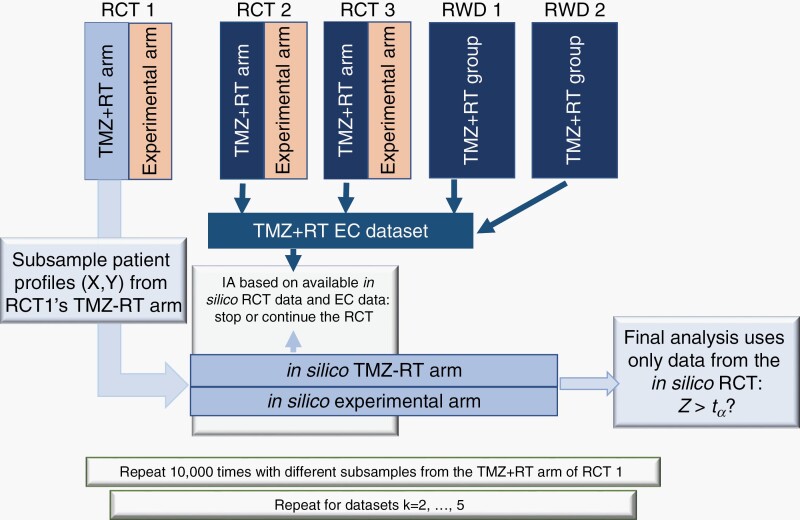

For each GBM study k = 1,…,5, we subsampled the data set to generate hypothetical RCTs and used the TMZ+RT patient records of the remaining four GBM data sets (k' ≠ k) as EC data (see also Figure 1). In particular, for each study k, we repeat the following steps 10 000 times:

Fig. 1.

Graphical representation of the model-free evaluations for the trial designs IA–ID, IA–EC, and IA–EC–X. For GBM data sets k (k = 1, 2, …, 5) we used the TRM+RT group of study k to generate an in silico RCT. The TMZ+RT groups in the remaining data sets (k' ≠ k) are used as EC group. The available data from the in silico RCT and the EC data (for IA–EC or IA–EC–X) for used for IAs. If the trial is not stopped at an IAs, then the final analysis involves only data from the in silico RCT. We generate 10 000 RCTs from GBM study k. We then repeat this process for all k = 1, 2, …, 5 GBM studies. Abbreviations: EC, external control; GBM, glioblastoma; IA, interim analysis; RCT, randomized clinical trial.

We randomly select (with replacement) N TMZ+RT patient records from the study, including pretreatment profiles X and outcomes Y. We use binary outcomes, survival after 12 months of treatment.

We randomize N1 < N patients to a hypothetical experimental arm and the remaining N − N1 to a hypothetical TMZ+RT SOC arm. Enrollment times are randomly generated, assuming on average 5 enrollments per month.

Patients treated with TMZ+RT in the remaining 4 studies constitute the EC data set.

We use the internal data (step 1) and the EC data (step 2) to conduct IAs with IA–ID, IA–EC, or IA–EC–X after the first n1,n2, … nj < N outcomes become available (12 months after the nj-th enrollment). The j-th IA does not use data on patients enrolled after the nj-th randomization.

Lastly, if the trial was not stopped at IAs, we conduct the final analysis using only the internal data (steps 1).

Since the outcomes of both, the experimental and control arms are sampled (step 1) from the TMZ+RT group of the GBM study, the treatment effect in the 10 000 generated RCTs is null.

We repeated steps (1–4) 10 000 times for each GBM study. We applied the described subsampling procedure separately to each GBM data set, to evaluate the operating characteristics of the RCT designs IA–ID, IA–EC, and IA–EC–X assuming (i) that the RCT population is identical to the subsampled population and (ii) using the remaining four data sets as EC for IA–EC–X and IA–EC. We can estimate several operating characteristics, like the probability of early termination of the RCT for futility.

To evaluate the operating characteristics in scenarios with positive treatment effects (TE > 0), we include an additional step (1.c) of the algorithm: each negative outcome (Y = 0) in our hypothetical experimental arm (step 1.b) is relabeled with probability π TE > 0 into a positive one (Y = 1).

Results

We first describe relevant operating characteristics of the outlined IAs (IA–ID, IA–EC, and IA–EC–X), and we discuss efficiency gains and risks associated to the integration of EC data. We then present validation analyses using the GBM data sets.

Model-based Evaluations

Table 1 summarizes seven simulation scenarios. In all seven the marginal probability of response to the SOC in the RCT population is Pr(Y = 1|A = 0) = 0.5. Using a z-test for proportions17 and α = 0.05 the trial (N = 182, 2:1 randomization) has approximately 80% power to detect a TE = 0.2 (Table 1, scenario 1). IAs are conducted after 36, 73, 109, and 146 outcomes become available. Each IA terminates the study if the predicted probability of a significant result (expression 1) is below the threshold b = 0.15.

Table 2 illustrates selected operating characteristics when the EC data set includes 1000 patients (the GBM data collection includes 1188 patients). The first three columns provide operating characteristics assuming that the experimental treatment has no effects, TE = 0, while the remaining columns correspond to a hypothetical superior (TE ≈ 0.19, log-odds ratio 0.85) experimental treatment.

Table 2.

Selected Operating Characteristics of Three Trial Designs With IA–ID, IA–EC, or IA–EC–X

| No Treatment Effect | Positive Treatment Effect | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IA | IA–ID | IA–EC | IA–EC–X | IA–ID | IA–EC | IA–EC–X |

| Scenario 1 | No effects of pretreatment variables on the outcomes, | |||||

| Average sample size | 80 | 66 | 66 | 161 | 171 | 171 |

| Average study durationa | 16 | 13 | 13 | 32 | 34 | 34 |

| % of Trials stopped at IA | 89 | 94 | 94 | 19 | 11 | 11 |

| Type I error rate/power % | 4 | 3 | 2 | 76 | 81 | 80 |

| Scenario 2 | No unmeasured prognostic variables, | |||||

| Average sample size | 80 | 66 | 65 | 159 | 169 | 169 |

| Average study durationa | 16 | 13 | 13 | 32 | 34 | 34 |

| % of Trials stopped at IA | 89 | 93 | 94 | 21 | 14 | 14 |

| Type I error rate/power % | 4 | 3 | 3 | 73 | 77 | 76 |

| Scenario 3 | No unmeasured prognostic variables, | |||||

| Average sample size | 80 | 91 | 65 | 159 | 177 | 168 |

| Average study durationa | 16 | 18 | 13 | 32 | 35 | 34 |

| % of Trials stopped at IA | 90 | 88 | 94 | 21 | 7 | 14 |

| Type I error rate/power % | 4 | 4 | 3 | 73 | 81 | 76 |

| Scenario 4 | No unmeasured prognostic variables, | |||||

| Average sample size | 80 | 49 | 65 | 160 | 148 | 168 |

| Average study durationa | 16 | 10 | 13 | 32 | 30 | 34 |

| % of Trials stopped at IA | 89 | 98 | 94 | 20 | 28 | 15 |

| Type I error rate/power % | 4 | 1 | 3 | 73 | 66 | 76 |

| Scenario 5 | Unmeasured prognostic variable X3, | |||||

| Average sample size | 80 | 77 | 78 | 157 | 173 | 171 |

| Average study durationa | 16 | 15 | 16 | 31 | 35 | 34 |

| % of Trials stopped at IA | 89 | 91 | 91 | 23 | 11 | 13 |

| Type I error rate/power % | 4 | 3 | 3 | 70 | 76 | 75 |

| Scenario 6 | Unmeasured prognostic variable X3, | |||||

| Average sample size | 80 | 102 | 76 | 157 | 178 | 173 |

| Average study durationa | 16 | 20 | 15 | 31 | 36 | 35 |

| % of Trials stopped at IA | 89 | 84 | 90 | 23 | 7 | 12 |

| Type I error rate/power % | 3 | 5 | 4 | 70 | 78 | 78 |

| Scenario 7 | Unmeasured prognostic variable X3, | |||||

| Average sample size | 80 | 44 | 56 | 157 | 133 | 154 |

| Average study durationa | 16 | 9 | 11 | 31 | 27 | 31 |

| % of Trials stopped at IA | 89 | 99 | 97 | 23 | 40 | 25 |

| Type I error rate/power % | 4 | 1 | 1 | 70 | 56 | 66 |

Abbreviations: EC, external control; IA, interim analysis; IC, internal control; RCT, randomized clinical trial. We consider 7 scenarios (Table 1), with various (i) distributions of three pretreatment variables in the EC, which in scenarios 3 to 7 are different from the RCT population, (ii) effects of pretreatment variables on the probabilities of positive outcomes, and (iii) treatment effects of the experimental arm relative to the control. For each scenario the table reports averages, across 10 000 simulations, of the sample size of the study, the study duration, and the proportion of studies that stopped early at IAs for futility.

aAverage study duration in the subset of simulations stopped early for futility.

In scenario 1 none of the three patient characteristics are prognostic. In this case, without using EC data (IA–ID), the average sample size is 80 patients when the experimental treatment is ineffective (TE = 0). IA–EC and IA–EC–X reduce the average size by 19% (66 vs 80 patients) when TE = 0. Moreover, the study duration is reduced on average by 3 months. The final testing procedure is identical across all simulated trials, and it does not involve EC data. Nonetheless, the use of EC data at IAs leads to higher power (81%, 80%, and 76% for IA–EC, IA–EC–X, and IA–ID) because the integration of EC data reduces the probability of early stopping for effective treatments (TE > 0).

In scenarios 2–4, the first two (out of three) pretreatment patient characteristics are prognostic. In scenario 2, the distribution of these two variables is identical in the EC and in the RCT populations. Whereas in scenario 3 (4), different distributions of the prognostic variables lead to marginal outcome probabilities P(Y = 1|EC) for the EC that are lower (higher) than in the RCT control arm (0.41 and 0.59 for the EC vs 0.5 for the RCT’s SOC arm; Table 1). The relative performances of IA–EC–X compared to IA–ID remain similar to scenarios 1. In contrast, the use of EC data without adjustments for prognostic characteristics (e.g., IA–EC) can reduce both the power (scenario 4) and the probability of early discontinuation when the TE = 0 (scenario 3).

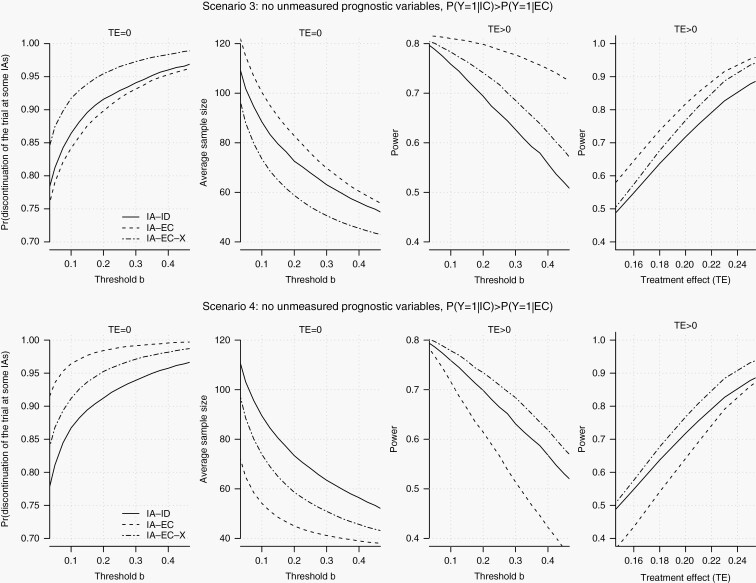

In Figure 2 and Supplementary Figures S1 and S2 we consider a range of early stopping thresholds b (expression 1) and different sizes of the EC data. The solid, dotted, and dashed lines correspond to IA–ID, IA–EC, and IA–EC–X. The rows of Figure 2 summarize operating characteristics for scenarios 3 and 4. With an ineffective experimental arm (TE = 0) IA–EC–X has a higher early stopping probability than IA–ID (left column). Moreover, for a range of possible values of the threshold b, IA–EC–X has also higher power (third column). In contrast IA–EC, which does not account for different distributions of prognostic variables in the EC and RCT populations, reduces power (scenario 4) and the probability of early discontinuation when TE ≤ 0 (scenario 3) compare to IA–ID.

Fig. 2.

Model-based evaluation of IA–ID, IA–EC, and IA–EC–X. We generate pretreatment patient characteristics X and outcomes Y from a statistical model. The parameters are specified in Table 1. The first column shows, for scenarios 3 (top row) and 4 (bottom row), the probability of stopping the RCT (y-axis), when the experimental treatment is ineffective (TE = 0), for different stopping thresholds b (x-axis) on the predictive probability of a significant result (expression 1). The second column shows the average sample size for a study that tests an ineffective experimental treatment (TE = 0). The third column shows, for the same scenarios, the RCT power (y-axis) for a range of stopping thresholds b (x-axis) when the TE > 0. The fourth column shows, for the same scenarios, the RCT power (y-axis) when we varied the treatment effect, , between 0.15 and 0.25 (x-axis) for a stopping threshold of b = 0.15. The EC data set includes 1000 patients. Abbreviations: EC, external control; IA, interim analysis; RCT, randomized clinical trial.

In the remaining scenarios (5–7, Table 1) a relevant pretreatment variable X3 is unmeasured and ignored by the IAs. In these scenarios, the type I error rate is bounded below the 5% level, because the EC data are not used in the final efficacy analysis. But, as expected, the probability of early stopping is influenced by the distributions of the unmeasured variable, which are different in the RCT and EC populations. For example, in scenario 7 IA–EC–X reduces the power of the trial compared to standard IA–ID. Indeed, a favorable distribution of X3 in the EC leads to frequent IA–EC–X early stopping decisions across RCT simulations with TE > 0. Symmetrically, the comparison of operating characteristics in scenarios 3 (where the unmeasured variable X3 and the outcome are independent) and 6 (where X3 is prognostic) reveals that unmeasured confounders can reduce the IA–EC–X discontinuation probabilities of ineffective treatments (TE ≤ 0).

Model-free Validation Analysis

We used the TMZ-RT arms of five GBM data sets6 to estimate operating characteristics of trial designs (IA–ID, IA–EC, and IA–EC–X). The primary outcome is overall survival after 12 months of treatment (OS-12).

The study (N = 105, 2:1 randomization) has approximately 80% power to detect an improvement in OS-12 from 0.69 (the average OS-12 rate in the GBM data sets) to 0.89 with a type I error rate of 5%. IAs and final analyses are conducted after 21, 42, 63, 84, and 105 observed outcomes. Three of the GBM data sets have a sample size of more than 105 patients, the AVAglio study and the DFCI and UCLA data sets. We subsampled these three studies to generate repeatedly RCTs and used the remaining four studies as EC data for IA–EC and IA–EC–X.

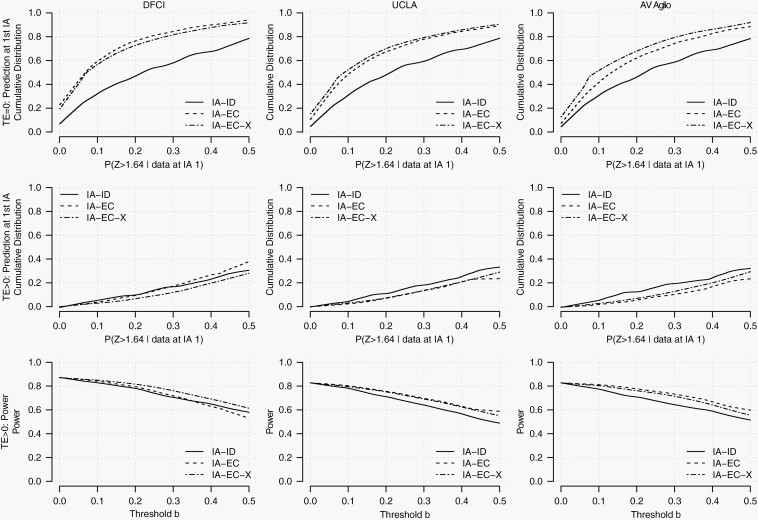

Figure 3 and Supplementary Figure S3 show selected operating characteristics when we subsampled the AVAglio, DFCI, and UCLA studies (columns 1 to 3) to generate RCTs. We considered an ineffective experimental arm (top row, TE = 0) and an effective experimental treatment (second and third row, TE ≈ 0.2). Figure 3 shows, for stopping thresholds b (expression 1) between 0 and 0.4 (x-axis), the proportion of generated RCTs with predictive probabilities below b (y-axis), which coincides with the frequency of early discontinuation decisions at the first IA. For example, with TE = 0 and b = 0.15, IA–EC–X and IA–ID discontinue, at the first IA, 58% and 40% of the RCTs generated by subsampling the DFCI data set.

Fig. 3.

Model-free evaluation of IA–ID, IA–EC, and IA–EC–X. We used individual-level data of patients treated with TMZ+RT from five GBM data sets. The first row shows, for an ineffective treatment (TE = 0), at the first IA, the cumulative distribution, across simulations, of the predictive probability (expression 1) that we used for early stopping. The second row shows the same cumulative distributions for an effective experimental treatment (TE > 0). The third row shows the power of the RCT (y-axis) with IA–ID, IA–EC, or IA–EC–X for potential early stopping thresholds b (x-axis) between 0 and 0.4. Abbreviations: EC, external control; GBM, glioblastoma; IA, interim analysis; RCT, randomized clinical trial.

The second row of Figure 3 shows that the use of EC data can reduce the likelihood of discontinuing the RCT when the GBM treatment is effective. For example, with a threshold b = 0.15, IA–ID discontinued at the first IA 8% (9%, 10%) of the RCTs with TE > 0 that we generated by subsampling the DFCI (UCLA, AVAglio) data set, compared to 4% (5% and 3%) for IA–EC–X. The third row of Figure 3 shows that when TE > 0, the IA–EC–X design has more power that IA–ID due to a reduced likelihood of early discontinuation of effective treatments.

The Supplementary Material includes IA–ID, IA-ED, and IA-ED-X procedures for time-to-event outcomes.

Discussion

RCTs are essential in the development of new treatments to demonstrate causal effects on clinical outcomes. Randomization balances potential confounders across treatment arms and reduces the risk of bias.26 Limitations of RCTs include long execution times,27 large sample sizes, and costs.28 The selection of control groups in clinical studies, both in RCTs and nonrandomized studies, has been discussed extensively.29–33 These contributions examined the impact on the scientific validity of the trial results and on the development of new effective treatments. We evaluated trial designs with two control groups, the EC group and the control arm of the trial. The EC data are used only for IAs. Our comparison of IA–EC and IA–EC–X designs illustrates that the integration of EC data for IAs requires adjustments (eg, regression or propensity score-based adjustments, etc.) to account for potential differences of pretreatment characteristics between the EC group and the RCT population.

The availability of patient-level data from completed clinical studies, electronic health records, and other health care data has the potential to reduce the costs and time to develop new treatments. The FDA and other regulatory agencies are participating in a scientific debate on trial designs that leverage external data, and on potential approaches in which external data may be useful for generating evidence of effectiveness.3,5,28 Recent data-sharing projects28,34–36 have created clinical databases and contributed to discussions on the importance of data sharing in the development of new therapeutics. Obstacles, incentives, and advantages of sharing data from previous clinical research have been previously discussed.37,38

The trial designs that we considered leverage EC data during the study to make futility early stopping decisions. But final analyses are solely based on outcome data from patients randomized during the RCT. The goal is to reduce the average study duration and the number of enrollments when the experimental treatment does not improve the primary outcome, while strictly controlling the rate of false-positive results. Our simulation study describes operating characteristics and the trade-off between efficiency gains and risks across scenarios representative of potential differences between the RCT population and the EC population.

Efficiency Gains

When the experimental treatment does not improve the primary outcomes, the internal and external populations are similar, or IAs account for all prognostic characteristics, our analyses illustrate reductions of the study duration and of the number of enrolled patients.

We also show a reduction of the probability of early discontinuation when there are clinically relevant treatment effects. This reduction translates into an increase in power when we compare IAs with (IA–EC–X) and without (IA–ID) integration of EC data.

Risks

We showed that if the patients enrolled in the RCT tend to have better prognostic profiles compared to the EC population, then the integration of EC data (IA–EC) reduces the early discontinuation probabilities of ineffective treatments relative to standard IA–ID.

Symmetrically, when the EC population tends to have better prognostic profiles, the IA–EC method increases the risk of discontinuing the development of effective treatments compared to standard IA–ID.

These two symmetric risks persist also for IA–EC–X, unless IAs account for all relevant prognostic pretreatment patient characteristics.

The comparison of the IA–EC and IA–EC–X designs indicates the importance of statistical adjustments, to account for potential differences between the distributions of relevant prognostic variables in the RCT and in the EC populations. Our simulations show that the IA–EC–X design has better operating characteristics compared to the IA–EC design.

To integrate EC data into IAs, it is necessary to verify that the definitions and measurement standards of pretreatment and outcome variables coincide in the RCT and in the EC group. For example, different imaging technologies and assessment schedules across studies impact on the measurement of progression-free survival (PFS)39,40 and objective response (OR).41,42 In turn, if the primary outcome is PFS or OR, these differences can introduce confounding and discrepancies between the study-specific outcome distributions. Therefore, EC data sets from studies with measurement standards misaligned with respect to the RCT cannot be used for the proposed IA–EC–X analyses. In addition, validation methods, such as the proposed cross-study algorithm (Methods section), are useful to scrutinize potential confounding mechanisms, such as inconsistent measurement standards across studies.

The IA–EC–X design requires to identify relevant pretreatment variables X (ie, all potential confounders). Literature reviews can be useful to list the potential confounders.6,43 If relevant patient characteristics are not available in the EC data, the IA–EC–X design should not be used. Indeed, our simulation study (scenarios 5–7, Table 2) illustrates that incomplete pretreatment profiles (ie, unmeasured confounders) can deteriorate the operating characteristics of the IA–EC–X design. The EC data and the list of potential confounders can be scrutinized, for example, with cross-study algorithms, to evaluate if they produce IAs with adequate operating characteristics.

The decision to integrate EC data into IAs can be supported by context-specific estimates of relevant operating characteristics and comparisons of candidate trial designs. We used a model-free evaluation algorithm to derive these estimates. It leverages GBM data sets from completed studies and computes projections of operating characteristics of various designs for future GBM trials. These analyses assume that the degree of heterogeneity between the populations of the available data sets is representative of potential differences between the population that will be enrolled during a future RCT and the EC group. Under this assumption the algorithm estimates the efficiency and risks of different study designs (eg, IA–ID, IA–EC, and IA–EC–X) that leverage different methodologies to integrate EC data or avoid the use of EC data. For example, in the Supplementary Material we compared the IA–EC–X design to an alternative Bayesian regression model that leverages pretreatment variables and propensity scores for predictions at IAs. The operating characteristics of these two approaches were nearly identical.

For IAs we used Bayesian predictions, assuming identical conditional outcome distributions Pr(Y|X, A = 0) for the external (EC data) and internal (RCT) control populations. Alternative IAs can be defined relaxing this assumption and modeling potential differences, for example, using Bayesian hierarchical priors.18 Alternatively, one can consider power or commensurate priors44,45 which allow investigators to tune the influence of the EC data on the IA. The validation approach that we described can be used to evaluate these and other definitions of IAs.

Our model-free comparison of different IAs is based on a limited number of GBM data sets. We observed similar results when we subsampled three distinct data sets to mimic RCTs and to compare IAs with and without the integration of EC data. This suggests that the integration of EC data into IAs (IA–EC–X) has limited risks and can reduce the study duration and the number of enrollments in GBM RCTs. Patient-level data from a larger collection of completed trials could strengthen this result. More generally, collections of patient-level data from clinical trials are essential to retrospectively evaluate (eg, using subsampling algorithms) statistical designs that leverage EC data.

Another limitation of our comparative analysis is that it does not generalize to disease settings beyond GBM, where the balance between efficiency gains and risks associated with the integration of EC data could be markedly different. Nonetheless, the subsampling algorithm can be applied to other collections of clinical data sets, to provide context-specific evaluations and comparisons of trial designs that leverage EC data.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study has not been previously presented.

Funding

The work of S.V. and L.T. was partially supported by Project Data Sphere and the NIH grant 1R01LM013352-01A1.

Conflict of interest statement. B.L. report employment at Project Data Sphere. B.M.A. and L.C. report employment at Foundation Medicine, Inc. All other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Authorship statement. Conception and design of the work, S.V., L.C., and L.T.; performance of the statistical analysis, S.V.; data collection and interpretation, all authors; prepared the manuscript, S.V. and L.T.; review and editing of the manuscript, all authors.

References

- 1. Hay M, Thomas DW, Craighead JL, Economides C, Rosenthal J. Clinical development success rates for investigational drugs. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32(1):40–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wong CH, Siah KW, Lo AW. Estimation of clinical trial success rates and related parameters. Biostatistics. 2019;20(2):366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Corrigan-Curay J, Sacks L, Woodcock J. Real-world evidence and real-world data for evaluating drug safety and effectiveness. JAMA. 2018;320(9):867–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Agarwala V, Khozin S, Singal G, et al. Real-world evidence in support of precision medicine: clinico-genomic cancer data as a case study. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(5):765–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Khozin S, Blumenthal GM, Pazdur R. Real-world data for clinical evidence generation in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;109(11):1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ventz S, Lai A, Cloughesy TF, Wen PY, Trippa L, Alexander BM. Design and evaluation of an external control arm using prior clinical trials and real-world data. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25(16):4993–5001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Viele K, Berry S, Neuenschwander B, et al. Use of historical control data for assessing treatment effects in clinical trials. Pharm Stat. 2014;13(1):41–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Carrigan G, Whipple S, Taylor MD, et al. An evaluation of the impact of missing deaths on overall survival analyses of advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients conducted in an electronic health records database. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2019;28(5):572–581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Curtis MD, Griffith SD, Tucker M, et al. Development and validation of a high-quality composite real-world mortality endpoint. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(6):4460–4476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lim J, Walley R, Yuan J, et al. Minimizing patient burden through the use of historical subject-level data in innovative confirmatory clinical trials: review of methods and opportunities. Ther Innov Regul Sci. 2018;52(5):546–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schmidli H, Häring DA, Thomas M, Cassidy A, Weber S, Bretz F. Beyond randomized clinical trials: use of external controls. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2020;107(4):806–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Betensky RA. Alternative derivations of a rule for early stopping in favor of H0. Am Stat. 2000;54(1):35–39. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Saville BR, Connor JT, Ayers GD, Alvarez J. The utility of Bayesian predictive probabilities for interim monitoring of clinical trials. Clinical Trials. 2014;11:485–493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Spiegelhalter DJ, Freedman LS, Blackburn PR. Monitoring clinical trials: conditional or predictive power? Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(1):8–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dmitrienko A, Wang MD. Bayesian predictive approach to interim monitoring in clinical trials. Stat Med. 2006;25(13):2178–2195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Vanderbeek AM, Rahman R, Fell G, et al. The clinical trials landscape for glioblastoma: is it adequate to develop new treatments? Neuro Oncol. 2018;20(8):1034–1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Agresti A. An Introduction to Categorical Data Analysis. 2nd ed. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gelman A, Carlin JB, Stern HS, Dunson DB, Vehtari A, Rubin DB. Bayesian Data Analysis.CRC Press; 2013. https://books.google.com/books?id=eSHSBQAAQBAJ&dq=gelman+Bayesian+data+analyses. Accessed June 24, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chinot OL, Wick W, Mason W, et al. Bevacizumab plus radiotherapy–temozolomide for newly diagnosed Glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(8):709–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cho DY, Yang WK, Lee HC, et al. Adjuvant immunotherapy with whole-cell lysate dendritic cells vaccine for glioblastoma multiforme: a phase II clinical trial. World Neurosurg. 2012;77(5–6):736–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lee EQ, Kaley TJ, Duda DG, et al. A multicenter, phase II, randomized, noncomparative clinical trial of radiation and temozolomide with or without vandetanib in newly diagnosed glioblastoma patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(16):3610–3618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(10):987–996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Thakkar JP, Dolecek TA, Horbinski C, et al. Epidemiologic and molecular prognostic review of glioblastoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014;23(10):1985–1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Curran WJ Jr, Scott CB, Horton J, et al. Recursive partitioning analysis of prognostic factors in three Radiation Therapy Oncology Group malignant glioma trials. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85(9):704–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lamborn KR, Chang SM, Prados MD. Prognostic factors for survival of patients with glioblastoma: recursive partitioning analysis. Neuro Oncol. 2004;6(3):227–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ratain MJ, Sargent DJ. Optimising the design of phase II oncology trials: the importance of randomisation. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(2):275–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gan HK, Grothey A, Pond GR, Moore MJ, Siu LL, Sargent D. Randomized phase II trials: inevitable or inadvisable? J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(15):2641–2647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bertagnolli MM, Sartor O, Chabner BA, et al. Advantages of a truly open-access data-sharing model. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(12):1178–1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. International Conference on Harmonisation; choice of control group and related issues in clinical trials; availability. Notice. Fed Regist. 2001;66(93):24390–24391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Colditz GA, Miller JN, Mosteller F. How study design affects outcomes in comparisons of therapy. I: medical. Stat Med. 1989;8(4):441–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ellenberg SS, Temple R. Placebo-controlled trials and active-control trials in the evaluation of new treatments. Part 2: practical issues and specific cases. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133(6):464–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Temple R, Ellenberg SS. Placebo-controlled trials and active-control trials in the evaluation of new treatments. Part 1: ethical and scientific issues. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133(6):455–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Castro M. Placebo versus best-available-therapy control group in clinical trials for pharmacologic therapies: which is better? Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2007;4(7):570–573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bierer BE, Li R, Barnes M, Sim I. A Global, neutral platform for sharing trial data. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(25):2411–2413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Krumholz HM, Waldstreicher J. The Yale Open Data Access (YODA) project—a mechanism for data sharing. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(5):403–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Schmidt H, Caldwell B, Mollet A, Leimer HG, Szucs T. An industry experience with data sharing. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(21):2081–2082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rubinstein SM, Warner JL. CancerLinQ: origins, implementation, and future directions. JCO Clin Cancer Inform. 2018;2:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Arfè A, Ventz S, Trippa L. Shared and usable data from phase 1 oncology trials—an unmet need. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6(7):980–981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Reardon DA, Ballman KV, Buckner JC, Chang SM, Ellingson BM. Impact of imaging measurements on response assessment in glioblastoma clinical trials. Neuro Oncol. 2014;16:v24–vii35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Korn RL, Crowley JJ. Overview: progression-free survival as an endpoint in clinical trials with solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(10):2607–2612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Aykan NF, Özatlı T. Objective response rate assessment in oncology: current situation and future expectations. World J Clin Oncol. 2020;11(2):53–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Smith AD, Shah SN, Rini BI, Lieber ML, Remer EM. Morphology, Attenuation, Size, and Structure (MASS) criteria: assessing response and predicting clinical outcome in metastatic renal cell carcinoma on antiangiogenic targeted therapy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;194(6):1470–1478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Greenland S. Invited commentary: variable selection versus shrinkage in the control of multiple confounders. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167(5):523–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hobbs BP, Carlin BP, Mandrekar SJ, Sargent DJ. Hierarchical commensurate and power prior models for adaptive incorporation of historical information in clinical trials. Biometrics. 2011;67(3):1047–1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ibrahim JG, Chen MH. Power prior distributions for regression models. Stat Sci. 2000;15(1):46–60. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.