Key Points

Question

Is the COVID-19 pandemic associated with changes in the reasons for suicide in Japan?

Findings

In this cross-sectional study of 21 027 reason-identified suicides, all categories of reasons for suicide had monthly excess suicide rates during the COVID-19 pandemic, except for school in men. There were gender differences in subcategories.

Meaning

The findings of this study could help to develop gender-specific suicide prevention interventions and programs.

This cross-sectional study assesses whether the COVID-19 pandemic was associated with changes in reasons for suicide among individuals in Japan.

Abstract

Importance

Although the suicide rate in Japan increased during the COVID-19 pandemic, the reasons for suicide have yet to be comprehensively investigated.

Objective

To assess which reasons for suicide had rates that exceeded the expected number of suicide deaths for that reason during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This national, population-based cross-sectional study of data on suicides gathered by the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare from January 2020 to May 2021 used a times-series analysis on the numbers of reason-identified suicides. Data of decedents were recorded by the National Police Agency and compiled by the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare.

Exposure

For category analysis, we compared data from January 2020 to May 2021 with data from December 2014 to June 2020. For subcategory analysis, data from January 2020 to May 2021 were compared with data from January 2019 to June 2020.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The main outcome was the monthly excess suicide rate, ie, the difference between the observed number of monthly suicide deaths and the upper bound of the 1-sided 95% CI for the expected number of suicide deaths in that month. Reasons for suicide were categorized into family, health, economy, work, relationships, school, and others, which were further divided into 52 subcategories. A quasi-Poisson regression model was used to estimate the expected number of monthly suicides. Individual regression models were used for each of the 7 categories, 52 subcategories, men, women, and both genders.

Results

From the 29 938 suicides (9984 [33.3%] women; 1093 [3.7%] aged <20 years; 3147 [10.5%] aged >80 years), there were 21 027 reason-identified suicides (7415 [35.3%] women). For both genders, all categories indicated monthly excess suicide rates, except for school in men. October 2020 had the highest excess suicide rates for all cases (observed, 1577; upper bound of 95% CI for expected number of suicides, 1254; 25.8% greater). In men, the highest monthly excess suicide rate was 24.3% for the other category in August 2020 (observed, 87; upper bound of 95% CI for expected number, 70); in women, it was 85.7% for school in August 2020 (observed, 26; upper bound of 95% CI for expected number, 14).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this study, observed suicides corresponding to all 7 categories of reasons exceeded the monthly estimates (based on data from before or during the COVID-19 pandemic), except for school-related reasons in men. This study can be used as a basis for developing intervention programs for suicide prevention.

Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO),1 suicide is a critical public health concern. Furthermore, research has shown that infectious diseases (eg, COVID-19) adversely affect mental health.2 Nonetheless, suicide rates in different countries seem to have been constant since the COVID-19 pandemic onset3,4,5,6; in contrast, Japan’s statistics have indicated an increasing trend.7,8 Worldwide, suicide rates tend to be higher in men than women.1,9,10 However, from July to October 2020 (ie, the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic), the rate of increase in suicide rates was higher among Japanese women than men.11,12 Therefore, the COVID-19 pandemic may be associated with changes in the reasons for suicide among the Japanese population.

Generally, the reasons for suicide tend to be multifactoral,13 and the following have been related to suicide: depression, environment, economic status, gender, and society14; sociocultural behavioral norms (ie, while men are less likely to engage in help-seeking behaviors owing to masculinism, women are more likely to do so10,15,16,17); and media reporting, as careless suicide reporting may trigger the Werther effect, ie, copycat suicides.18,19 Additionally, the following have been associated with poorer mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: interpersonal distress, parenting challenges, marital discord, alienation, and loneliness.20,21,22,23

In Japan, suicide was a major public health issue even before the COVID-19 pandemic. In 1998, the annual number of suicide cases exceeded 32 000, and similar numbers were recorded until 2010.24 In Japanese culture, men are supposed to be family breadwinners and women, the caregivers and homemakers.25 Accordingly, the most identified reason for suicide among employed Japanese men has been economic problems.26 A strong social stigma also prevents suicide from being thoroughly investigated in Japan.24 Amid this reality, the WHO asked the Japanese government to devise countermeasures to curb national suicide rates.24 In 2006, the Japanese government passed the Basic Act on Suicide Prevention, aimed at preventing suicide.27 As a result, suicide numbers dropped to less than 30 000 in 2012; suicide ratios were the highest in 2013 (27.0 per 100 000 people) and the lowest in 2019 (16.0 per 100 000 people).24

To prevent the spread of COVID-19, the Japanese government issued various restrictive measures (eg, limited public transportation) that could have induced psychological distress and job loss nationwide28,29,30; these negative consequences of the battle against COVID-19 may have affected men and women differently. During school closures because of COVID-19, Japanese mothers had worsened mental health, while fathers did not.30 Furthermore, depression has been associated with the role of family caregiver, and being a woman was a risk factor for suicidal behaviors during the pandemic.31,32,33 Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, risk factors for depression, anxiety, and physical health were disproportionally higher in Japanese women than in men.33,34 Additionally, ever since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been an increase in suicide rates among women, a phenomenon that has also been observed internationally.35,36

Considering that the period of increase in suicide rates during the COVID-19 pandemic has been the longest compared with that of all other large-scale natural disasters,37 it is necessary to implement optimal suicide prevention measures in Japan. Furthermore, although several studies have highlighted that the COVID-19 pandemic has heightened the risk of poor mental health, few have used national-level data to examine suicide in this period. A systematic review has warned about the low quality of the design and sampling of extant studies,38 and studies that used national-level data to examine mental health burden owing to the COVID-19 pandemic39,40,41,42 have not directly explored the reasons for suicide. This study aimed to assess which reasons for suicide had higher monthly numbers during the COVID-19 pandemic than the estimated number of suicide deaths for that month.

Methods

For this national-level cross-sectional time-series analysis, we extracted publicly available data from government sources on the number of suicide deaths for which the reason was known (ie, reason-identified suicide). Although we used only publicly available data, we obtained approval from the Medical Ethics Review Committee of the University of Miyazaki and adhered to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) and the International COVID-19 Suicide Prevention Research Collaboration reporting guidelines.43 Informed consent was waived because this study used secondary data.

National Suicide Statistics

In Japan, statistics on suicide are compiled by the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare (MHLW), recorded by the National Police Agency (NPA), and often used in related studies.8,10,11 In Japan, only doctors can prepare death certificates, and the Medical Practitioners Law stipulates that an abnormal death must be reported to the NPA within 24 hours.44 Through criminal investigation, the NPA must examine all corpses with abnormal causes of death and determine the cause of death; they conduct physiological tests, examine suicide notes and emails, conduct interviews with family members, and assess documents (eg, doctor’s notes, medical certificates, loans).45,46,47 The national record system requires the NPA to register 1 to 3 reasons for suicide, an action aimed at helping improve suicide prevention strategies.48 After accumulating data, the number of suicide deaths and their reasons are published by biological sex and age group (10-year increments), except for those younger than 19 or older than 80 years. To ensure confidentiality, the data set does not contain exact age, gender, or geographical information.

According to the Suicide Countermeasures Basic Law established in 2007 by the Japanese government,48 there are 7 categories (and 52 subcategories) of reasons for suicide: family, health, economy, work, relationship, school, others (eg, copycat suicide), and unknown. We excluded the unknown category because the NPA updates statistics when the suicide was identified.

There are 52 subcategories, as follows: for family, there are parent-child problems, marital discord, other family discords, death of a family member, pessimism about the future of the family, abuse from family, child-rearing problems, abuse, caregiving fatigue, and others. For health, there are physical illness, depression, schizophrenia, alcoholism, drug and substance abuse, other mental disorders, physical disability, and others. For economy, there are bankruptcy, business slump, unemployment, job failure, poverty, multiple debts, joint guarantee, other debts, debt collection trouble, suicide for insurance, and others. For work, there are work failure, workplace relationships, work environment changes, work fatigue, and others. For relationships, there are marriage, heartbreak, infidelity, other relationship distress, and others. For school, there are admission, academic path, academic failure, issues with teachers, bullying, schoolmate trouble, and others. For others, there are discovery of a crime, victim of crime, copycat suicide, loneliness, neighborhood trouble, and others.

Statistical Analysis

Although monthly data on the categories are available from January 2010, data on the subcategories are available only from January 2019. Therefore, for the 7 categories, we used monthly data from January 2010 to May 2021 (latest data available as of July 2021); for the subcategories, and to analyze data since the first COVID-19 case in Japan (ie, January 2020), we used monthly data from January 2019 to May 2021.

We used quasi-Poisson regression to estimate the expected number of monthly suicide deaths. To assess the parameters of the quasi-Poisson regression, we used the Farrington algorithm.49,50 We constructed separate models for men, women, both genders combined, all cases, each category, and each subcategory. For the categories, we assumed that the number of suicide deaths in a month during the COVID-19 pandemic would remain similar to that recorded in the past 5 years for that given month and the months immediately before and after; then, we estimated the extent to which the observed number of monthly suicide deaths differed from this assumption.51,52 For the subcategories (ie, available from 2019), we used data from 1 month before and 1 year after the corresponding month.

In each estimation, we incorporated a trend term (ie, data trends over time, such as a constant increase or decrease) and seasonality (ie, a regular pattern of changes) into the model. The monthly excess suicide rates were calculated by the formula: observed suicides minus the upper bound of the 95% CI of the expected number of suicides, divided by the upper bound. The results were interpreted as the suicide burden associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. For this 1-sided analysis, we defined statistical significance at 5%. We used R version 4.1.0 (R Project for Statistical Computing) for all analyses and graphical representations and the surveillance package for the Farrington algorithm.52

Results

Overall Observations

In the 17 months between January 2020 and May 2021, 29 938 people died of suicide (9984 [33.3%] women; 1093 [3.7%] aged <20 years; 3147 [10.5%] aged >80 years) (Table 1; eTable 1 in the Supplement). In total, there were 21 027 reason-identified suicides (70.2%; 7415 [35.3%] women). More than 70% of suicides without an identified reason were among men (6342 [71.2%]). A χ2 analysis indicated a significant difference between men and women in the percentage of suicides with a known or unknown reason (χ21 = 116.3; P < .001).

Table 1. Suicides Overall and by Gender From January 2020 to May 2021 by Age Group.

| Group | All ages, No. | Individuals by age group, No. (%) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤19 y | 20-29 y | 30-39 y | 40-49 y | 50-59 y | 60-69 y | 70-79 y | ≥80 y | Unknown | ||

| Total | ||||||||||

| Both genders | 29 938 | 1093 (3.7) | 3664 (12.2) | 3697 (12.3) | 5106 (17.1) | 4922 (16.4) | 3954 (13.2) | 4265 (14.2) | 3147 (10.5) | 90 (0.3) |

| Men | 19 954 | 657 (3.3) | 2427 (12.2) | 2634 (13.2) | 3527 (17.7) | 3404 (17.1) | 2641 (13.2) | 2675 (13.4) | 1912 (9.6) | 77 (0.4) |

| Women | 9984 | 436 (4.4) | 1237 (12.4) | 1063 (10.6) | 1579 (15.8) | 1518 (15.2) | 1313 (13.2) | 1590 (15.9) | 1235 (12.4) | 13 (0.1) |

| Reason-identified suicides | ||||||||||

| Both genders | 21 027 | 699 (3.3) | 2520 (12.0) | 2641 (12.6) | 3561 (16.9) | 3465 (16.5) | 2856 (13.6) | 3045 (14.5) | 2230 (10.6) | 10 (<0.1) |

| Men | 13 612 | 388 (2.9) | 1624 (11.9) | 1820 (13.4) | 2392 (17.6) | 2325 (17.1) | 1878 (13.8) | 1850 (13.6) | 1327 (9.7) | 8 (0.1) |

| Women | 7415 | 311 (4.2) | 896 (12.1) | 821 (11.1) | 1169 (15.8) | 1140 (15.4) | 978 (13.2) | 1195 (16.1) | 903 (12.2) | 2 (<0.1) |

| Reasons | ||||||||||

| Family | ||||||||||

| Both genders | 4382 | 191 (4.4) | 415 (9.5) | 594 (13.6) | 803 (18.3) | 750 (17.1) | 547 (12.5) | 606 (13.8) | 476 (10.9) | 0 |

| Men | 2567 | 104 (4.1) | 246 (9.6) | 364 (14.2) | 497 (19.4) | 419 (16.3) | 324 (12.6) | 337 (13.1) | 276 (10.8) | 0 |

| Women | 1815 | 87 (4.8) | 169 (9.3) | 230 (12.7) | 306 (16.9) | 331 (18.2) | 223 (12.3) | 269 (14.8) | 200 (11) | 0 |

| Health | ||||||||||

| Both genders | 13 940 | 237 (1.7) | 1110 (8.0) | 1376 (9.9) | 2130 (15.3) | 2239 (16.1) | 2172 (15.6) | 2673 (19.2) | 1997 (14.3) | 6 (<0.1) |

| Men | 7796 | 98 (1.3) | 539 (6.9) | 755 (9.7) | 1167 (15.0) | 1263 (16.2) | 1256 (16.1) | 1534 (19.7) | 1179 (15.1) | 5 (0.1) |

| Women | 6144 | 139 (2.3) | 571 (9.3) | 621 (10.1) | 963 (15.7) | 976 (15.9) | 916 (14.9) | 1139 (18.5) | 818 (13.3) | 1 (<0.1) |

| Economy | ||||||||||

| Both genders | 4578 | 20 (0.4) | 582 (12.7) | 713 (15.6) | 977 (21.3) | 1105 (24.1) | 765 (16.7) | 336 (7.3) | 76 (1.7) | 4 (0.1) |

| Men | 3964 | 14 (0.4) | 499 (12.6) | 622 (15.7) | 861 (21.7) | 960 (24.2) | 685 (17.3) | 272 (6.9) | 48 (1.2) | 3 (0.1) |

| Women | 614 | 6 (1.0) | 83 (13.5) | 91 (14.8) | 116 (18.9) | 145 (23.6) | 80 (13.0) | 64 (10.4) | 28 (4.6) | 1 (0.2) |

| Work | ||||||||||

| Both genders | 2690 | 47 (1.7) | 576 (21.4) | 541 (20.1) | 689 (25.6) | 576 (21.4) | 202 (7.5) | 49 (1.8) | 10 (0.4) | 0 |

| Men | 2241 | 38 (1.7) | 430 (19.2) | 445 (19.9) | 585 (26.1) | 509 (22.7) | 180 (8.0) | 45 (2.0) | 9 (0.4) | 0 |

| Women | 449 | 9 (2.0) | 146 (32.5) | 96 (21.4) | 104 (23.2) | 67 (14.9) | 22 (4.9) | 4 (0.9) | 1 (0.2) | 0 |

| Relationships | ||||||||||

| Both genders | 1112 | 83 (7.5) | 343 (30.8) | 320 (28.8) | 214 (19.2) | 103 (9.3) | 28 (2.5) | 18 (1.6) | 3 (0.3) | 0 |

| Men | 654 | 47 (7.2) | 171 (26.1) | 205 (31.3) | 124 (19.0) | 67 (10.2) | 25 (3.8) | 13 (2) | 2 (0.3) | 0 |

| Women | 458 | 36 (7.9) | 172 (37.6) | 115 (25.1) | 90 (19.7) | 36 (7.9) | 3 (0.7) | 5 (1.1) | 1 (0.2) | 0 |

| School | ||||||||||

| Both genders | 552 | 303 (54.9) | 235 (42.6) | 13 (2.4) | 1 (0.2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Men | 353 | 171 (48.4) | 171 (48.4) | 11 (3.1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Women | 199 | 132 (66.3) | 64 (32.2) | 2 (1.0) | 1 (0.5) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Others | ||||||||||

| Both genders | 1704 | 82 (4.8) | 248 (14.6) | 205 (12.0) | 268 (15.7) | 229 (13.4) | 205 (12.0) | 234 (13.7) | 233 (13.7) | 0 |

| Men | 1151 | 47 (4.1) | 168 (14.6) | 148 (12.9) | 195 (16.9) | 173 (15.0) | 138 (12.0) | 158 (13.7) | 124 (10.8) | 0 |

| Women | 553 | 35 (6.3) | 80 (14.5) | 57 (10.3) | 73 (13.2) | 56 (10.1) | 67 (12.1) | 76 (13.7) | 109 (19.7) | 0 |

| Unknown reason | ||||||||||

| Both genders | 8911 | 394 (4.4) | 1144 (12.8) | 1056 (11.9) | 1545 (17.3) | 1457 (16.4) | 1098 (12.3) | 1220 (13.7) | 917 (10.3) | 80 (0.9) |

| Men | 6342 | 269 (4.2) | 803 (12.7) | 814 (12.8) | 1135 (17.9) | 1079 (17.0) | 763 (12.0) | 825 (13.0) | 585 (9.2) | 69 (1.1) |

| Women | 2569 | 125 (4.9) | 341 (13.3) | 242 (9.4) | 410 (16.0) | 378 (14.7) | 335 (13.0) | 395 (15.4) | 332 (12.9) | 11 (0.4) |

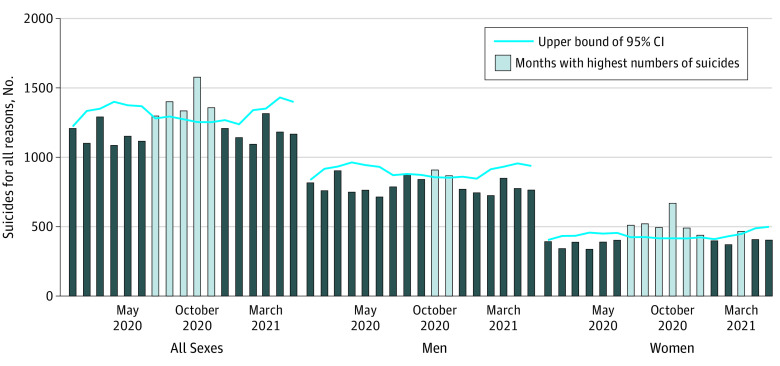

In the quasi-Poisson regression model of the total number of reason-identified suicides, there were 5 months in which the number of deaths exceeded the assumption (ie, July to November 2020) (Figure). In men, there were 2 months with excess suicide rates (October and November 2020); in women, there were 7, with 6 being consecutive months (July to December 2020 and March 2021). By month, October 2020 had the highest excess suicide rates for all cases (observed, 1577; upper bound of 95% CI for expected number of suicides, 1254; 25.8% greater) (Table 2). Among the 7 categories, the highest excess suicide rate for all cases was related to health in October 2020 (observed, 1099; upper bound of 95% CI for expected number, 831; 32.3% greater) (Table 3; eFigure 1 in the Supplement). In women, we observed excess suicide rates for 5 consecutive months in family, health, and work and for 6 consecutive months in other reason.

Figure. Suicides Overall and by Gender From January 2020 to May 2021.

Information about how the expected number of suicides per month appears in the Methods section.

Table 2. Expected and Observed Number of Monthly Suicides and Percentage Change From January 2020 to May 2021 Overall and by Gender.

| Month and year | Both genders | Men | Women | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expected (upper bound), No. | Observed, No. | Change, % | Expected (upper bound), No. | Observed, No. | Change, % | Expected (upper bound), No. | Observed, No. | Change, % | |

| Jan 2020 | 1101 (1222) | 1208 | −1.1 | 746 (837) | 816 | −2.5 | 360 (404) | 392 | −3.0 |

| Feb 2020 | 1177 (1334) | 1101 | −17.5 | 802 (917) | 759 | −17.2 | 381 (433) | 342 | −21.0 |

| Mar 2020 | 1194 (1350) | 1291 | −4.4 | 816 (933) | 903 | −3.2 | 379 (434) | 388 | −10.6 |

| Apr 2020 | 1265 (1400) | 1086 | −22.4 | 863 (963) | 749 | −22.2 | 409 (457) | 337 | −26.3 |

| May 2020 | 1225 (1375) | 1152 | −16.2 | 833 (944) | 763 | −19.2 | 400 (450) | 389 | −13.6 |

| Jun 2020 | 1220 (1368) | 1116 | −18.4 | 820 (931) | 714 | −23.3 | 399 (455) | 402 | −11.6 |

| Jul 2020 | 1160 (1280) | 1297 | 1.3a | 781 (871) | 787 | −9.6 | 378 (424) | 510 | 20.3a |

| Aug 2020 | 1156 (1294) | 1400 | 8.2a | 780 (880) | 880 | 0.0 | 376 (425) | 520 | 22.4a |

| Sep 2020 | 1137 (1274) | 1334 | 4.7a | 771 (873) | 840 | −3.8 | 366 (416) | 494 | 18.8a |

| Oct 2020 | 1139 (1254) | 1577 | 25.8a | 768 (856) | 908 | 6.1a | 371 (416) | 669 | 60.8a |

| Nov 2020 | 1115 (1253) | 1357 | 8.3a | 750 (853) | 867 | 1.6a | 365 (415) | 490 | 18.1a |

| Dec 2020 | 1131 (1268) | 1208 | −4.7 | 758 (860) | 770 | −10.5 | 373 (423) | 438 | 3.5a |

| Jan 2021 | 1118 (1238) | 1142 | −7.8 | 755 (846) | 744 | −12.1 | 363 (410) | 398 | −2.9 |

| Feb 2021 | 1200 (1340) | 1094 | −18.4 | 812 (914) | 724 | −20.8 | 380 (431) | 370 | −14.2 |

| Mar 2021 | 1211 (1351) | 1315 | −2.7 | 824 (932) | 849 | −8.9 | 392 (447) | 466 | 4.3a |

| Apr 2021 | 1292 (1431) | 1182 | −17.4 | 859 (956) | 775 | −18.9 | 427 (488) | 407 | −16.6 |

| May 2021 | 1247 (1399) | 1167 | −16.6 | 828 (938) | 764 | −18.6 | 430 (499) | 403 | −19.2 |

A month with the observed number of suicides exceeding the 95% upper bound of the expected number of suicides for that month. Percentage change was defined as the difference between the observed number of suicides for a month and the 95% upper bound of the expected number of suicides for that month divided by the threshold.

Table 3. Expected and Observed Number of Monthly Suicides and Percentage Change by Reasons for Suicide, Overall and by Gender.

| Month and year | Both genders | Men | Women | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expected (upper bound), No. | Observed, No. | Change, % | Expected (upper bound), No. | Observed, No. | Change, % | Expected (upper bound), No. | Observed, No. | Change, % | |

| Family | |||||||||

| Jan 2020 | 228 (262) | 238 | −9.2 | 141 (167) | 148 | −11.4 | 88 (108) | 90 | −16.7 |

| Feb 2020 | 245 (284) | 228 | −19.7 | 152 (180) | 142 | −21.1 | 92 (112) | 86 | −23.2 |

| Mar 2020 | 249 (288) | 302 | 4.9a | 152 (181) | 195 | 7.7a | 97 (118) | 107 | −9.3 |

| Apr 2020 | 260 (296) | 209 | −29.4 | 159 (186) | 139 | −25.3 | 102 (122) | 70 | −42.6 |

| May 2020 | 248 (284) | 234 | −17.6 | 151 (177) | 154 | −13.0 | 97 (118) | 80 | −32.2 |

| Jun 2020 | 244 (281) | 247 | −12.1 | 146 (173) | 144 | −16.8 | 98 (119) | 103 | −13.4 |

| Jul 2020 | 239 (271) | 244 | −10.0 | 141 (165) | 126 | −23.6 | 98 (118) | 118 | 0.0 |

| Aug 2020 | 242 (276) | 268 | −2.9 | 142 (166) | 169 | 1.8a | 100 (121) | 99 | −18.2 |

| Sep 2020 | 236 (270) | 291 | 7.8a | 139 (164) | 163 | −0.6 | 98 (119) | 128 | 7.6a |

| Oct 2020 | 232 (263) | 313 | 19.0a | 138 (161) | 148 | −8.1 | 94 (114) | 165 | 44.7a |

| Nov 2020 | 225 (261) | 297 | 13.8a | 134 (159) | 169 | 6.3a | 91 (112) | 128 | 14.3a |

| Dec 2020 | 229 (266) | 257 | −3.4 | 139 (166) | 139 | −16.3 | 90 (111) | 118 | 6.3a |

| Jan 2021 | 231 (264) | 247 | −6.4 | 142 (167) | 127 | −24.0 | 88 (108) | 120 | 11.1a |

| Feb 2021 | 249 (286) | 242 | −15.4 | 154 (180) | 135 | −25.0 | 95 (116) | 107 | −7.8 |

| Mar 2021 | 254 (292) | 271 | −7.2 | 157 (186) | 154 | −17.2 | 96 (118) | 117 | −0.8 |

| Apr 2021 | 264 (303) | 243 | −19.8 | 163 (190) | 164 | −13.7 | 101 (124) | 79 | −36.3 |

| May 2021 | 251 (289) | 251 | −13.1 | 153 (179) | 151 | −15.6 | 99 (121) | 100 | −17.4 |

| Health | |||||||||

| Jan 2020 | 711 (794) | 740 | −6.8 | 421 (479) | 424 | −11.5 | 294 (334) | 316 | −5.4 |

| Feb 2020 | 740 (843) | 697 | −17.3 | 449 (523) | 416 | −20.5 | 303 (346) | 281 | −18.8 |

| Mar 2020 | 765 (871) | 806 | −7.5 | 458 (531) | 478 | −10.0 | 307 (356) | 328 | −7.9 |

| Apr 2020 | 813 (904) | 734 | −18.8 | 493 (560) | 421 | −24.8 | 335 (382) | 313 | −18.1 |

| May 2020 | 805 (905) | 795 | −12.2 | 488 (560) | 453 | −19.1 | 329 (374) | 342 | −8.6 |

| Jun 2020 | 826 (931) | 829 | −11.0 | 490 (560) | 472 | −15.7 | 336 (389) | 357 | −8.2 |

| Jul 2020 | 767 (853) | 958 | 12.3a | 467 (528) | 523 | −0.9 | 316 (364) | 435 | 19.5a |

| Aug 2020 | 750 (845) | 997 | 18.0a | 460 (527) | 560 | 6.3a | 308 (357) | 437 | 22.4a |

| Sep 2020 | 750 (848) | 892 | 5.2a | 450 (515) | 475 | −7.8 | 300 (347) | 417 | 20.2a |

| Oct 2020 | 755 (831) | 1099 | 32.3a | 442 (500) | 522 | 4.4a | 313 (360) | 577 | 60.3a |

| Nov 2020 | 736 (828) | 879 | 6.2a | 431 (498) | 497 | −0.2 | 309 (354) | 382 | 7.9a |

| Dec 2020 | 742 (838) | 769 | −8.2 | 426 (488) | 435 | −10.9 | 316 (364) | 334 | −8.2 |

| Jan 2021 | 713 (794) | 714 | −10.1 | 420 (478) | 389 | −18.6 | 299 (345) | 325 | −5.8 |

| Feb 2021 | 755 (853) | 699 | −18.1 | 448 (513) | 405 | −21.1 | 310 (359) | 294 | −18.1 |

| Mar 2021 | 782 (880) | 795 | −9.7 | 463 (530) | 442 | −16.6 | 325 (376) | 353 | −6.1 |

| Apr 2021 | 845 (940) | 775 | −17.6 | 491 (553) | 433 | −21.7 | 364 (423) | 342 | −19.1 |

| May 2021 | 852 (968) | 762 | −21.3 | 489 (561) | 451 | −19.6 | 369 (433) | 311 | −28.2 |

| Economy | |||||||||

| Jan 2020 | 242 (292) | 321 | 9.9a | 212 (257) | 284 | 10.5a | 32 (43) | 37 | −14.0 |

| Feb 2020 | 266 (320) | 278 | −13.1 | 233 (282) | 254 | −9.9 | 35 (47) | 24 | −48.9 |

| Mar 2020 | 267 (325) | 328 | 0.9a | 245 (302) | 291 | −3.6 | 34 (47) | 37 | −21.3 |

| Apr 2020 | 298 (357) | 275 | −23.0 | 260 (314) | 238 | −24.2 | 38 (50) | 37 | −26.0 |

| May 2020 | 273 (325) | 233 | −28.3 | 239 (287) | 203 | −29.3 | 35 (47) | 30 | −36.2 |

| Jun 2020 | 266 (322) | 182 | −43.5 | 231 (282) | 162 | −42.6 | 36 (49) | 20 | −59.2 |

| Jul 2020 | 245 (292) | 225 | −22.9 | 214 (258) | 190 | −26.4 | 32 (43) | 35 | −18.6 |

| Aug 2020 | 249 (298) | 228 | −23.5 | 217 (260) | 193 | −25.8 | 33 (45) | 35 | −22.2 |

| Sep 2020 | 249 (302) | 287 | −5.0 | 221 (273) | 252 | −7.7 | 32 (44) | 35 | −20.5 |

| Oct 2020 | 257 (310) | 302 | −2.6 | 224 (272) | 250 | −8.1 | 34 (45) | 52 | 15.6a |

| Nov 2020 | 247 (296) | 265 | −10.5 | 216 (262) | 226 | −13.7 | 34 (47) | 39 | −17.0 |

| Dec 2020 | 258 (314) | 292 | −7.0 | 226 (280) | 248 | −11.4 | 35 (48) | 44 | −8.3 |

| Jan 2021 | 263 (321) | 274 | −14.6 | 231 (284) | 243 | −14.4 | 33 (44) | 31 | −29.5 |

| Feb 2021 | 286 (342) | 242 | −29.2 | 260 (312) | 206 | −34.0 | 35 (49) | 36 | −26.5 |

| Mar 2021 | 292 (357) | 311 | −12.9 | 256 (314) | 269 | −14.3 | 36 (50) | 42 | −16.0 |

| Apr 2021 | 301 (362) | 271 | −25.1 | 262 (318) | 238 | −25.2 | 40 (52) | 33 | −36.5 |

| May 2021 | 277 (332) | 264 | −20.5 | 241 (292) | 217 | −25.7 | 38 (52) | 47 | −9.6 |

| Work | |||||||||

| Jan 2020 | 154 (184) | 171 | −7.1 | 138 (166) | 144 | −13.3 | 16 (23) | 27 | 17.4a |

| Feb 2020 | 162 (192) | 120 | −37.5 | 143 (171) | 108 | −36.8 | 18 (26) | 12 | −53.8 |

| Mar 2020 | 164 (197) | 170 | −13.7 | 145 (174) | 148 | −14.9 | 19 (28) | 22 | −21.4 |

| Apr 2020 | 174 (205) | 132 | −35.6 | 152 (180) | 113 | −37.2 | 22 (30) | 19 | −36.7 |

| May 2020 | 170 (201) | 130 | −35.3 | 148 (177) | 111 | −37.3 | 22 (30) | 19 | −36.7 |

| Jun 2020 | 165 (197) | 121 | −38.6 | 144 (173) | 100 | −42.2 | 21 (31) | 21 | −32.3 |

| Jul 2020 | 155 (183) | 171 | −6.6 | 135 (162) | 132 | −18.5 | 20 (28) | 39 | 39.3a |

| Aug 2020 | 153 (183) | 161 | −12.0 | 134 (161) | 131 | −18.6 | 20 (29) | 30 | 3.4a |

| Sep 2020 | 149 (180) | 164 | −8.9 | 129 (157) | 126 | −19.7 | 20 (30) | 38 | 26.7a |

| Oct 2020 | 149 (177) | 214 | 20.9a | 129 (155) | 173 | 11.6a | 20 (29) | 41 | 41.4a |

| Nov 2020 | 147 (180) | 200 | 11.1a | 129 (159) | 164 | 3.1a | 18 (27) | 36 | 33.3a |

| Dec 2020 | 150 (182) | 164 | −9.9 | 131 (160) | 141 | −11.9 | 19 (28) | 23 | −17.9 |

| Jan 2021 | 148 (179) | 160 | −10.6 | 130 (159) | 138 | −13.2 | 17 (26) | 22 | −15.4 |

| Feb 2021 | 156 (190) | 135 | −28.9 | 135 (165) | 122 | −26.1 | 21 (30) | 13 | −56.7 |

| Mar 2021 | 154 (188) | 189 | 0.5a | 131 (162) | 155 | −4.3 | 23 (35) | 34 | −2.9 |

| Apr 2021 | 164 (198) | 134 | −32.3 | 137 (167) | 107 | −35.9 | 28 (40) | 27 | −32.5 |

| May 2021 | 158 (192) | 154 | −19.8 | 134 (166) | 128 | −22.9 | 28 (41) | 26 | −36.6 |

| Relationships | |||||||||

| Jan 2020 | 57 (70) | 67 | −4.3 | 36 (47) | 42 | −10.6 | 19 (29) | 25 | −13.8 |

| Feb 2020 | 57 (71) | 57 | −19.7 | 37 (48) | 32 | −33.3 | 20 (29) | 25 | −13.8 |

| Mar 2020 | 56 (69) | 67 | −2.9 | 36 (46) | 42 | −8.7 | 20 (30) | 25 | −16.7 |

| Apr 2020 | 56 (70) | 39 | −44.3 | 36 (47) | 28 | −40.4 | 21 (30) | 11 | −63.3 |

| May 2020 | 59 (72) | 68 | −5.6 | 37 (48) | 43 | −10.4 | 21 (30) | 25 | −16.7 |

| Jun 2020 | 59 (73) | 36 | −50.7 | 37 (48) | 22 | −54.2 | 23 (32) | 14 | −56.2 |

| Jul 2020 | 61 (75) | 74 | −1.3 | 37 (48) | 44 | −8.3 | 24 (34) | 30 | −11.8 |

| Aug 2020 | 61 (75) | 88 | 17.3a | 36 (47) | 45 | −4.3 | 25 (35) | 43 | 22.9a |

| Sep 2020 | 59 (73) | 75 | 2.7a | 34 (45) | 44 | −2.2 | 25 (35) | 31 | −11.4 |

| Oct 2020 | 59 (73) | 94 | 28.8a | 35 (46) | 49 | 6.5a | 24 (33) | 45 | 36.4a |

| Nov 2020 | 58 (72) | 76 | 5.6a | 36 (47) | 41 | −12.8 | 21 (30) | 35 | 16.7a |

| Dec 2020 | 61 (75) | 58 | −22.7 | 38 (50) | 30 | −40.0 | 22 (31) | 28 | −9.7 |

| Jan 2021 | 60 (76) | 65 | −14.5 | 37 (48) | 40 | −16.7 | 23 (33) | 25 | −24.2 |

| Feb 2021 | 60 (76) | 56 | −26.3 | 37 (48) | 38 | −20.8 | 24 (33) | 18 | −45.5 |

| Mar 2021 | 57 (73) | 70 | −4.1 | 35 (46) | 34 | −26.1 | 24 (34) | 36 | 5.9a |

| Apr 2021 | 59 (77) | 69 | −10.4 | 35 (46) | 46 | 0.0 | 23 (34) | 23 | −32.4 |

| May 2021 | 60 (78) | 53 | −32.1 | 36 (48) | 34 | −29.2 | 25 (35) | 19 | −45.7 |

| School | |||||||||

| Jan 2020 | 28 (39) | 38 | −2.6 | 20 (30) | 27 | −10.0 | 7 (14) | 11 | −21.4 |

| Feb 2020 | 31 (43) | 36 | −16.3 | 23 (33) | 25 | −24.2 | 8 (15) | 11 | −26.7 |

| Mar 2020 | 32 (44) | 36 | −18.2 | 24 (34) | 28 | −17.6 | 8 (14) | 8 | −42.9 |

| Apr 2020 | 32 (45) | 27 | −40.0 | 24 (35) | 17 | −51.4 | 8 (14) | 10 | −28.6 |

| May 2020 | 28 (40) | 27 | −32.5 | 21 (32) | 21 | −34.4 | 7 (12) | 6 | −50.0 |

| Jun 2020 | 26 (37) | 29 | −21.6 | 18 (28) | 13 | −53.6 | 8 (14) | 16 | 14.3a |

| Jul 2020 | 24 (35) | 24 | −31.4 | 17 (27) | 12 | −55.6 | 7 (12) | 12 | 0.0 |

| Aug 2020 | 29 (41) | 54 | 31.7a | 21 (32) | 28 | −12.5 | 8 (14) | 26 | 85.7a |

| Sep 2020 | 31 (43) | 32 | −25.6 | 23 (33) | 18 | −45.5 | 7 (13) | 14 | 7.7a |

| Oct 2020 | 31 (42) | 32 | −23.8 | 23 (33) | 21 | −36.4 | 7 (13) | 11 | −15.4 |

| Nov 2020 | 29 (41) | 43 | 4.9a | 20 (31) | 29 | −6.5 | 8 (14) | 14 | 0.0 |

| Dec 2020 | 30 (42) | 27 | −35.7 | 21 (31) | 14 | −54.8 | 9 (16) | 13 | −18.8 |

| Jan 2021 | 34 (46) | 27 | −41.3 | 23 (34) | 20 | −41.2 | 12 (19) | 7 | −63.2 |

| Feb 2021 | 37 (50) | 28 | −44.0 | 25 (37) | 17 | −54.1 | 12 (20) | 11 | −45.0 |

| Mar 2021 | 39 (52) | 38 | −26.9 | 28 (39) | 25 | −35.9 | 11 (19) | 13 | −31.6 |

| Apr 2021 | 36 (49) | 28 | −42.9 | 26 (38) | 21 | −44.7 | 12 (20) | 7 | −65.0 |

| May 2021 | 32 (44) | 26 | −40.9 | 22 (33) | 17 | −48.5 | 11 (19) | 9 | −52.6 |

| Others | |||||||||

| Jan 2020 | 80 (98) | 85 | −13.3 | 58 (73) | 58 | −20.5 | 22 (31) | 27 | −12.9 |

| Feb 2020 | 81 (102) | 84 | −17.6 | 58 (74) | 65 | −12.2 | 23 (33) | 19 | −42.4 |

| Mar 2020 | 83 (104) | 99 | −4.8 | 60 (75) | 72 | −4.0 | 23 (33) | 27 | −18.2 |

| Apr 2020 | 88 (107) | 96 | −10.3 | 64 (78) | 75 | −3.8 | 25 (34) | 21 | −38.2 |

| May 2020 | 84 (104) | 86 | −17.3 | 62 (76) | 60 | −21.1 | 23 (33) | 26 | −21.2 |

| Jun 2020 | 82 (102) | 90 | −11.8 | 59 (73) | 55 | −24.7 | 23 (33) | 35 | 6.1a |

| Jul 2020 | 78 (95) | 110 | 15.8a | 56 (69) | 67 | −2.9 | 23 (32) | 43 | 34.4a |

| Aug 2020 | 80 (99) | 124 | 25.3a | 57 (70) | 87 | 24.3a | 23 (33) | 37 | 12.1a |

| Sep 2020 | 80 (99) | 107 | 8.1a | 58 (72) | 69 | −4.2 | 22 (32) | 38 | 18.8a |

| Oct 2020 | 81 (97) | 121 | 24.7a | 60 (73) | 66 | −9.6 | 21 (30) | 55 | 83.3a |

| Nov 2020 | 84 (102) | 121 | 18.6a | 61 (75) | 76 | 1.3a | 22 (32) | 45 | 40.6a |

| Dec 2020 | 85 (103) | 98 | −4.9 | 61 (75) | 66 | −12.0 | 23 (33) | 32 | −3.0 |

| Jan 2021 | 84 (101) | 95 | −5.9 | 61 (74) | 67 | −9.5 | 24 (33) | 28 | −15.2 |

| Feb 2021 | 89 (109) | 87 | −20.2 | 63 (77) | 61 | −20.8 | 25 (36) | 26 | −27.8 |

| Mar 2021 | 92 (112) | 97 | −13.4 | 66 (80) | 68 | −15.0 | 27 (40) | 29 | −27.5 |

| Apr 2021 | 99 (118) | 99 | −16.1 | 69 (83) | 71 | −14.5 | 31 (44) | 28 | −36.4 |

| May 2021 | 97 (121) | 105 | −13.2 | 65 (80) | 68 | −15.0 | 29 (42) | 37 | −11.9 |

A month with the observed number of suicides exceeding the 95% upper bound of the expected number of suicides for that month. Percentage change was defined as the difference between the observed number of suicides for a month and the 95% upper bound of the expected number of suicides for that month divided by the threshold.

Reasons for Suicide Among Men

In men, the subcategories that showed 2 months with excess suicide rates were parent-child problems (range, 3.4%-13.0%), physical illness (range, 3.0%-4.8%), physical disability (both months, 5.0%), other debts (range, 1.9%-12.5%), work failure (range, 3.4%-6.9%), work fatigue (range, 2.0%-34.1%), heartbreak (range, 16.7%-17.6%), academic failure (range, 8.3%-16.7%), and loneliness (range, 7.4%-25.0%) (eTable 2 and eFigure 2 in the Supplement). The subcategories that showed 1 month with excess suicide rates were death of a family member (3.8%), unemployment (42.9%), workplace relationships (18.6%), work environment changes (8.3%), infidelity (9.1%), other relationship distress (28.6%), discovery of a crime (4.5%), copycat suicide (14.3%), and other reasons, such as affected by a disaster (27.6%). The highest monthly excess suicide rate was 24.3% for the other category in August 2020 (observed, 87; upper bound of 95% CI for expected number, 70).

Reasons for Suicide Among Women

The workplace relationships subcategory showed 4 months with excess suicide rates (range, 6.2%-18.2%). The subcategories that showed 3 months with excess suicide rates were poverty (range, 5.9%-26.3%) and work failure (range, 20.0%-40.0%) (eTable 3 and eFigure 3 in the Supplement).

The subcategories that showed 2 months with excess suicide rates were parent-child problems (range, 4.2%-4.5%), marital discord (range, 4.3%-39.1%), other family discords (range, 6.2%-7.1%), child-rearing problems (range, 22.2%-40.0%), physical illness (range, 15.4%-20.4%), depression (range, 15.1%-34.2%), infidelity (range, 7.7%-22.2%), and other relationship distress (range, 13.3%-30.0%). The subcategories showing 1 month with excess suicide rates were caregiving fatigue (25.0%), schizophrenia (26.1%), alcoholism (45.5%), other mental disorders (18.6%), business slump (20.0%), multiple debts (16.7%), work fatigue (13.3%), schoolmate trouble (60.0%), and copycat suicide (12.5%). The highest monthly excess suicide rate was 85.7% for school in August 2020 (observed, 26; upper bound of 95% CI for expected number, 14).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this was the first study to examine whether the COVID-19 pandemic was associated with changes in reasons for suicide in Japan. Overall, the excess trends for suicides in our study concur with those in prior research.7,8 Furthermore, in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, there seems to have been a lack of excessive numbers for suicide worldwide; this may owe to the pulling together phenomenon,53,54 wherein a crisis temporally reinforces social bonds. Nonetheless, we observed excess suicide rates around July 2020, during the onset of the second COVID-19 wave in Japan; this wave may have been associated with a diminished sense of social bonding.

The category school demonstrated the highest excess suicide rate in October 2020, although its subcategories did not corroborate this excess. This spike might be because of the accumulated stress from unstable school schedules, school closures, and the sudden shift to online education, all of which started in March 2020.55 Considering that the younger generation experiences high levels of stress and is at risk for suicide,35,56 there is a critical need for educational interventions within schools on the mental health effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, which have shown to be effective.57

We observed that women showed excess suicide rates across all categories. Men did not have an excess rate for school, although they did for all other categories. Despite these gender differences, there were excess suicide rates in almost all categories, indicating that the COVID-19 pandemic evoked multilayered psychological distresses in Japan; this concurs with prior international research.20,21,22,23

Reasons for Suicide in Men

Our results suggested that, generally, work-related stress (eg, work failure, fatigue) was associated with suicide in men. This is consistent with previous studies,20,40,58 although these studies did not inspect gender differences. In Japan in 2016, men owned 80% of the households;60 in 2015, male full-time employees tended to have a median monthly income 25.7% higher than that of their female counterparts.59 Thus, men remain the main breadwinners of their households nationwide. The economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic seems to have been severe enough for many men to resort to suicide. Thus, relevant stakeholders (eg, employment assistance programs, company-based employee benefit programs) and occupational health services need to provide men in vulnerable work-related circumstances with social and mental health support via telecommunication or online services.60,61

We observed higher suicide rates with an unknown reason among men, which may be explained by gender differences in help-seeking behavior. Globally, men tend to engage in less help-seeking behaviors for psychological hardships than women.15,16,17 In Japan, while men tended to not leave suicide notes, women did leave them.62 In our results for men, the subcategories of heartbreak, relationship distress, and loneliness showed rates that were significantly higher than the estimations for some months. In a systematic review,21 psychosocial factors (eg, social isolation) were shown to be significant risk factors of suicide, a finding that concurs with our evidence. Therefore, we see the need for suicide prevention campaigns tailored to men, such as those using male role models,63 that promote mental health support.

Reasons for Suicide in Women

Previous studies reporting higher suicide rates in women than men speculated reasons for suicide that included job loss and caregiver roles.11,12 In our study, we observed that both these factors and health problems may be associated with substantial burden in Japanese women. Furthermore, women showed excess suicide rates across several consecutive months, demonstrating that the COVID-19 pandemic may have burdened several aspects of their lives. Our findings for women correspond to those in previous studies,18,19,20,21,38 although we provide more detailed data on the potential reasons for their suicide. It is possible that school closures, telecommuting, an increase in caregiver role, and restrictions in access to health services were associated with women spending more time with family members; this may have been associated with the excess suicide rates we observed by exacerbating parent-child problems, other family discords, child-rearing problems, and caregiving fatigue.

We also observed excess suicide rates associated with depression, schizophrenia, alcoholism, and other mental disorders in women. Research shows that preexisting mental health problems are a risk factor for suicide.17 As suicide tends to be associated with various factors,17 we suggest that health care professionals inquire about women’s life changes since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, provide psychosocial support, assess the risk of suicide, and consider referral to a psychiatrist when relevant.

Copycat Suicide

From 1989 to 2010, the 10 days following a media report of the suicide of a well-known Japanese figure tended to accompany an increase in the number of copycat suicides.64 Considering this and the excess suicide rates we observed for copycat suicide in women, our results seem to indicate the possibility of the Werther effect in Japanese women. Nonetheless, our results for copycat suicides in men showed excess suicide rates throughout April, a period inconsistent with that for women. A systematic review on this topic65 showed that age and gender have a strong modeling effect on suicide. We could not identify possible reasons for this gender difference.

Regarding the prevention of copycat suicides, research shows that this can be operationalized through media cooperation43; 2 studies66,67 demonstrated that people searched for suicide-related information on the internet (ie, through search engines and social media) during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. Online news and social media platforms should be cautious when reporting suicide-related information.

Limitations

This study has limitations. Our data set has potential bias and errors owing to the fact that those who die by suicide cannot report on the actual reasoning behind their act. However, we did use data from national agency sources, which we deemed the most reliable sources at the time of this research.

Second, we excluded 30% of our data on suicide deaths, as these were categorized under the reason unknown. Moreover, our χ2 analysis comparing reason-identified suicides and unknown reason suicides by gender yielded significant results. Thus, if the reasons in the missing data greatly differ from those in the reason-identified suicides we used, the exclusion of this portion of the data may have affected our findings.

Third, there is a potential lack of accuracy for our data on reasons for suicide; nonetheless, there are no current scientific measures that can accurately determine the true reasons behind a suicide, so we still deem the governmental data set we used the most reliable source among those currently available.

Fourth, although the Farrington algorithm is a well-established methodology, it has yet to receive an extension that enables including covariates; this hindered our ability to include geographical factors in the model. Furthermore, it is possible that factors other than the COVID-19 pandemic were associated with the suicide cases we analyzed.

Fifth, as suicide is also influenced by culture and religion,17 there are clear limitations regarding the generalizability of our results. Despite these limits, we believe that our findings shed light on the reasons for suicide amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

Conclusions

This study found that the COVID-19 pandemic may be associated with various changes in the reasons for suicide in Japan. We observed excess suicide rates in all categories, albeit with differences in subcategories by gender. In women, the categories of family, health, work, and other showed excess suicide rates that lasted from 5 to 6 consecutive months. We hope that our data are used as a basis for the development of suicide prevention interventions and programs.

eFigure 1. Number of Suicides by the 7 Categories of Reasons for Suicide

eFigure 2. Subcategories of Reasons for Suicide With Rates Exceeding the Upper Bound of the 95% CI for a Month Among Men

eFigure 3. Subcategories of Reasons for Suicide With Rates Exceeding the Upper Bound of the 95% CI for a Month Among Women

eTable 1. Number of Suicides by Age and Subcategory, January 2020 to May 2021

eTable 2. Expected and Observed Number of Monthly Suicides and Percentage Change From January 2020 to May 2021 by 52 Subcategories Among Men

eTable 3. Expected and Observed Number of Monthly Suicides and Percentage Change From January 2020 to May 2021 by 52 Subcategories Among Women

References

- 1.World Health Organization . Suicide in the World: Global Health Estimates. World Health Organization; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zortea TC, Brenna CTA, Joyce M, et al. The impact of infectious disease-related public health emergencies on suicide, suicidal behavior, and suicidal thoughts. Crisis. 2021;42(6):474-487. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.John A, Pirkis J, Gunnell D, Appleby L, Morrissey J. Trends in suicide during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ. 2020;371:m4352. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m4352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Appleby L, Richards N, Ibrahim S, Turnbull P, Rodway C, Kapur N. Suicide in England in the COVID-19 pandemic: early observational data from real time surveillance. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2021;4:100110. doi: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2021.100110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Faust JS, Shah SB, Du C, Li S-X, Lin Z, Krumholz HM. Suicide deaths during the COVID-19 stay-at-home advisory in Massachusetts, March to May 2020. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(1):e2034273. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.34273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pirkis J, John A, Shin S, et al. Suicide trends in the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic: an interrupted time-series analysis of preliminary data from 21 countries. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8(7):579-588. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00091-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anzai T, Fukui K, Ito T, Ito Y, Takahashi K. Excess mortality from suicide during the early COVID-19 pandemic period in Japan: a time-series modeling before the pandemic. J Epidemiol. 2021;31(2):152-156. doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20200443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tanaka T, Okamoto S. Increase in suicide following an initial decline during the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan. Nat Hum Behav. 2021;5(2):229-238. doi: 10.1038/s41562-020-01042-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Naghavi M; Global Burden of Disease Self-Harm Collaborators . Global, regional, and national burden of suicide mortality 1990 to 2016: systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. BMJ. 2019;364:l94. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dwyer J, Dwyer J, Hiscock R, et al. COVID-19 as a context in suicide: early insights from Victoria, Australia. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2021;45(5):517-522. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.13132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sakamoto H, Ishikane M, Ghaznavi C, Ueda P. Assessment of suicide in Japan during the COVID-19 pandemic vs previous years. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(2):e2037378. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.37378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nomura S, Kawashima T, Harada N, et al. Trends in suicide in Japan by gender during the COVID-19 pandemic, through December 2020. Psychiatry Res. 2021;300:113913. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gunnell D, Appleby L, Arensman E, et al. ; COVID-19 Suicide Prevention Research Collaboration . Suicide risk and prevention during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(6):468-471. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30171-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Whiteford HA, Degenhardt L, Rehm J, et al. Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2013;382(9904):1575-1586. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61611-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ito K, Hisanaga F, Akiko I. Suicide and gender, sexuality. Off J Natl Inst Ment Health NCNP Jpn. 2003;16(49):27-33. Accessed December 28, 2021. https://warp.da.ndl.go.jp/info:ndljp/pid/9956847/www.ncnp.go.jp/nimh/pdf/kenkyu49_sp.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murphy GE. Why women are less likely than men to commit suicide. Compr Psychiatry. 1998;39(4):165-175. doi: 10.1016/S0010-440X(98)90057-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldsmith SK, Pellmar TC, Kleinman AM, Bunney WE. Reducing Suicide: A National Imperative. National Academies Press; 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thorson J, Öberg P-A. Was there a suicide epidemic after Goethe’s Werther? Arch Suicide Res. 2003;7(1):69-72. doi: 10.1080/13811110301568 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leonard EC Jr. Confidential death to prevent suicidal contagion: an accepted, but never implemented, nineteenth-century idea. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2001;31(4):460-466. doi: 10.1521/suli.31.4.460.22043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Galea S, Merchant RM, Lurie N. The mental health consequences of COVID-19 and physical distancing: the need for prevention and early intervention. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(6):817-818. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.1562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leaune E, Samuel M, Oh H, Poulet E, Brunelin J. Suicidal behaviors and ideation during emerging viral disease outbreaks before the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic rapid review. Prev Med. 2020;141:106264. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395(10227):912-920. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ettman CK, Abdalla SM, Cohen GH, Sampson L, Vivier PM, Galea S. Prevalence of depression symptoms in US adults before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(9):e2019686-e2019686. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.19686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.World Health Organization . Preventing Suicide: A Global Imperative. World Health Organization; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Balarmino B and Roberts MR. Japanese gender role expectations and attitudes: a qualitative analysis of gender inequity. J Int Women’s Study. 2019;20(7):272-288. https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol20/iss7/18 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare & National Police Agency . Suicides in 2019. Accessed November 13, 2021. https://www.npa.go.jp/safetylife/seianki/jisatsu/R02/R01_jisatuno_joukyou.pdf

- 27.The Library of Congress . Japan: Basic Act on Suicide Prevention Amended. Accessed November 13, 2021. https://www.loc.gov/item/global-legal-monitor/2016-06-07/japan-basic-act-on-suicide-prevention-amended/

- 28.Yamamoto T, Uchiumi C, Suzuki N, Yoshimoto J, Murillo-Rodriguez E. The psychological impact of “mild lockdown” in Japan during the COVID-19 pandemic: a nationwide survey under a declared state of emergency. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(24):E9382. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17249382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cabinet Office . Group of indicators for satisfaction and quality of life. Accessed July 24, 2021. https://www5.cao.go.jp/keizai2/wellbeing/manzoku/index.html

- 30.Fujino Y, Ishimaru T, Eguchi H, et al. Protocol for a nationwide internet-based health survey of workers during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. J UOEH. 2021;43(2):217-225. doi: 10.7888/juoeh.43.217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yamamura E, Tsustsui Y. School closures and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan. J Popul Econ. 2021;34:1261-1298. doi: 10.1007/s00148-021-00844-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Noguchi T, Hayashi T, Kubo Y, Tomiyama N, Ochi A, Hayashi H. Association between family caregivers and depressive symptoms among community-dwelling older adults in Japan: a cross-sectional study during the COVID-19 pandemic. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2021;96:104468. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2021.104468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yoshioka T, Okubo R, Tabuchi T, Odani S, Shinozaki T, Tsugawa Y. Factors associated with serious psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan: a nationwide cross-sectional internet-based study. BMJ Open. 2021;11(7):e051115. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-051115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kimura M, Kimura K, Ojima T. Relationships between changes due to COVID-19 pandemic and the depressive and anxiety symptoms among mothers of infants and/or preschoolers: a prospective follow-up study from pre-COVID-19 Japan. BMJ Open. 2021;11(2):e044826. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-044826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dubé JP, Smith MM, Sherry SB, Hewitt PL, Stewart SH. Suicide behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic: a meta-analysis of 54 studies. Psychiatry Res. 2021;301:113998. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Connor J, Madhavan S, Mokashi M, et al. Health risks and outcomes that disproportionately affect women during the COVID-19 pandemic: a review. Soc Sci Med. 2020;266:113364. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Osaki Y, Otsuki H, Imamoto A, et al. Suicide rates during social crises: changes in the suicide rate in Japan after the Great East Japan earthquake and during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Psychiatr Res. 2021;140:39-44. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.05.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rogers JP, Chesney E, Oliver D, et al. Suicide, self-harm and thoughts of suicide or self-harm in infectious disease epidemics: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2021;30:e32. doi: 10.1017/S2045796021000214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shi L, Lu Z-A, Que J-Y, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors associated with mental health symptoms among the general population in China during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(7):e2014053-e2014053. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.14053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Czeisler MÉ, Lane RI, Wiley JF, Czeisler CA, Howard ME, Rajaratnam SMW. Follow-up survey of US adult reports of mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic, September 2020. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(2):e2037665. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.37665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.John A, Eyles E, Webb RT, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on self-harm and suicidal behaviour: update of living systematic review. F1000Res. 2020;9:1097. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.25522.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Steeg S, Bojanić L, Tilston G, et al. Temporal trends in primary care-recorded self-harm during and beyond the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic: time series analysis of electronic healthcare records for 2.8 million patients in the Greater Manchester Care Record. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;41:101175. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Knipe D, Hawton K, Siynor M, Niederkrotenthaler T. Researchers must contribute to responsible reporting of suicide. BMJ. 2021;372(n351):n351. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ministry of Justice, Japan . Medical Practitioners’ Act. Japanese Law Translation. Accessed November 13, 2021. http://www.japaneselawtranslation.go.jp/law/detail/?id=2074&vm=04&re=02

- 45.Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare . Suicide statistics: basic data on suicide in the community. Accessed July 18, 2021. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/0000140901.html

- 46.Otsuka Y, Horita Y. Statistics on suicides of Japanese workers. Jpn Labor Rev. 2013;10:44-54. [Google Scholar]

- 47.National Police Agency . On death investigation system to prevent crime oversight. Accessed November 13, 2021. https://www.npa.go.jp/bureau/criminal/souichi/gijiyoushi.pdf

- 48.The Library of Congress . Japan: two laws adopted to improve use of autopsies. Accessed November 13, 2021. https://www.loc.gov/item/global-legal-monitor/2012-06-25/japan-two-laws-adopted-to-improve-use-of-autopsies/

- 49.Farrington CP, Andrews NJ, Beale AD, Catchpole MA. A Statistical algorithm for the early detection of outbreaks of infectious disease. J R Stat Soc Ser A Stat Soc. 1996;159(3):547-563. doi: 10.2307/2983331 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Noufaily A, Enki DG, Farrington P, Garthwaite P, Andrews N, Charlett A. An improved algorithm for outbreak detection in multiple surveillance systems. Stat Med. 2013;32(7):1206-1222. doi: 10.1002/sim.5595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nomura S, Kawashima T, Yoneoka D, et al. Trends in suicide in Japan by gender during the COVID-19 pandemic, up to September 2020. Psychiatry Res. 2021;295:113622. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Salmon M, Schumacher D, Höhle M.. Monitoring count time series in R: aberration detection in public health surveillance. J Stat Softw. 2016;70(10):1-35. doi: 10.18637/jss.v070.i10 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Madianos MG, Evi K. Trauma and natural disaster: the case of earthquakes in Greece. J Loss Trauma. 2010;15(2):138-150. doi: 10.1080/15325020903373185 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gordon KH, Bresin K, Dombeck J, Routledge C, Wonderlich JA. The impact of the 2009 Red River Flood on interpersonal risk factors for suicide. Crisis. 2011;32(1):52-55. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.National Center for Child Health and Development . National online survey of children’s quality of life and health in the COVID-19 pandemic-Interim report. Accessed August 13, 2021. https://www.ncchd.go.jp/en/news/2020/20200514e.pdf

- 56.Pieh C, Plener PL, Probst T, Dale R, Humer E. Assessment of mental health of high school students during social distancing and remote schooling during the COVID-19 pandemic in Austria. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(6):e2114866-e2114866. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.14866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Akena D, Kiguba R, Muhwezi WW, et al. The effectiveness of a psycho-education intervention on mental health literacy in communities affected by the COVID-19 pandemic: a cluster randomized trial of 24 villages in central Uganda: a research protocol. Trials. 2021;22(1):446. doi: 10.1186/s13063-021-05391-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Portal Site of Official Statistics of Japan . Household owner by gender. Accessed November 20, 2021. https://www.e-stat.go.jp/dbview?sid=0003161347

- 59.Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development . The pursuit of gender equality: an uphill battle. Accessed August 19, 2021. https://www.oecd.org/japan/Gender2017-JPN-en.pdf

- 60.Ripp J, Peccoralo L, Charney D. Attending to the emotional well-being of the health care workforce in a New York City health system during the COVID-19 pandemic. Acad Med. 2020;95(8):1136-1139. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mheidly N, Fares MY, Fares J. Coping with stress and burnout associated with telecommunication and online learning. Front Public Health. 2020;8:574969. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.574969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Komada Y, Noguchi H, Ishihara A. Suicide and suicide notes. Article in Japanese. Ment Health Res. 2003;(16):75-79. Accessed August 19, 2021. https://www.ncnp.go.jp/nimh/pdf/kenkyu49_sp.pdf

- 63.Sagar-Ouriaghli I, Godfrey E, Bridge L, Meade L, Brown JSL. Improving mental health service utilization among men: a systematic review and synthesis of behavior change techniques within interventions targeting help-seeking. Am J Mens Health. 2019;13(3):1557988319857009. doi: 10.1177/1557988319857009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ueda M, Mori K, Matsubayashi T. The effects of media reports of suicides by well-known figures between 1989 and 2010 in Japan. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43(2):623-629. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyu056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sisask M, Värnik A. Media roles in suicide prevention: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2012;9(1):123-138. doi: 10.3390/ijerph9010123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ayers JW, Poliak A, Johnson DC, et al. Suicide-related internet searches during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(1):e2034261. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.34261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fahey RA, Matsubayashi T, Ueda M. Tracking the Werther effect on social media: emotional responses to prominent suicide deaths on twitter and subsequent increases in suicide. Soc Sci Med. 2018;219:19-29. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Oe H, Otsuka T. An empirical survey of Japanese life insurance customers: comparative market analysis based on consumers’ recognition data. Yu-cho Foundation. 2005. Accessed August 19, 2021. https://www.yu-cho-f.jp/research/old/research/repo/ooe_otsuka0627dp.pdf

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure 1. Number of Suicides by the 7 Categories of Reasons for Suicide

eFigure 2. Subcategories of Reasons for Suicide With Rates Exceeding the Upper Bound of the 95% CI for a Month Among Men

eFigure 3. Subcategories of Reasons for Suicide With Rates Exceeding the Upper Bound of the 95% CI for a Month Among Women

eTable 1. Number of Suicides by Age and Subcategory, January 2020 to May 2021

eTable 2. Expected and Observed Number of Monthly Suicides and Percentage Change From January 2020 to May 2021 by 52 Subcategories Among Men

eTable 3. Expected and Observed Number of Monthly Suicides and Percentage Change From January 2020 to May 2021 by 52 Subcategories Among Women