Abstract

Background.

Prior research on prenatal cocaine exposure (PCE) indicates that exposed children experience behavioral dysregulation resulting in risky adolescent behavior including earlier initiation of cannabis use and sexual intercourse. The goal of this study was to examine the long-term effects of PCE on adult sexual behavior.

Methods.

This is a prospective cohort study of the association between PCE and risky adult sexual behavior and sexually transmitted infections (STIs) in 202 young adults (mean age = 27, SD = 0.98 years). The sample was 55% female, 46% White, and 54% Black. Data from the prenatal, childhood, and adolescent phases of the study were used to delineate pathways from PCE to adult sexual behavior.

Results.

The most common risky sexual behavior was having sex while drunk or high (63%). One-third of the sample reported that they “almost always” had sex while drunk or high. We found evidence for an indirect pathway from PCE to adult sex while drunk or high via early cannabis initiation. There were no other effects of PCE on adult risky sexual behavior or on risk for STIs, after controlling for sex assigned at birth, race, age at sexual initiation, and family history of drug and alcohol problems.

Conclusions.

Although PCE has been associated with earlier initiation of sex in prior studies, PCE was not directly associated with risky adult sex or history of STI. Exposed individuals were at greater risk of sex under the influence of alcohol or drugs via earlier initiation of cannabis use during adolescence.

Keywords: cannabis, marijuana, prenatal marijuana, prenatal, sex, risky sex

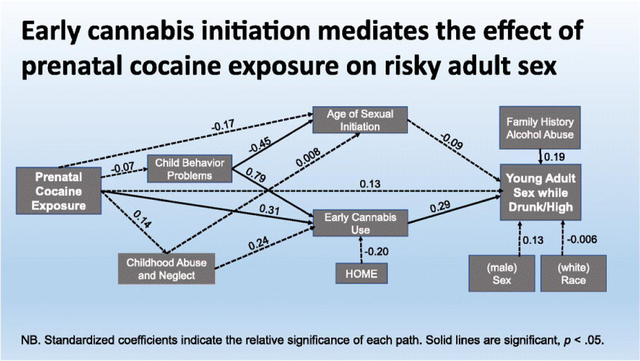

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

From a behavioral teratology framework, the effects of prenatal cocaine exposure (PCE) may lead to subtle deficits in the central nervous system and subsequent changes in behavior in exposed offspring that emerge well past infancy, as well as in a variety of domains (Vorhees, 1989). In fact, individuals prenatally exposed to cocaine are more likely to have problems with behavioral inhibition across childhood and adolescence that manifest in different outcomes. In several longitudinal cohort studies, PCE predicted externalizing behavior problems (Bada et al., 2012; Min et al., 2014; 2018; Minnes et al., 2010; Richardson et al., 2009; 2011; 2013a; 2015). Not surprisingly, PCE also predicted early initiation of drug use, especially adolescent cannabis use (Frank et al., 2011; Lester et al., 2012; Min et al., 2014; Richardson et al., 2013b; 2019). However, the evidence for the effects of PCE on substance use later in adolescence is mixed, with some studies finding an effect (Bandstra et al., 2015; Min et al., 2014; Minnes et al., 2014; 2017) and others reporting none (e.g., Bennett & Lewis, 2020) or none on more problematic levels of substance use (e.g., Frank et al., 2014). During young adulthood, PCE has been linked to difficulties with emotion regulation, Conduct Disorder, and arrests (Richardson et al., 2019) but again, not all studies report associations between PCE and adult functioning (Forman et al., 2017). Nonetheless, there is converging evidence that children with PCE experience behavioral dysregulation and earlier initiation of substance use.

A few studies have examined sexual behavior as a function of PCE. Lambert and colleagues (2013) reported that individuals with PCE were more likely to engage in sexual touching by age 13 and/or oral/penetrative sexual intercourse by age 14; this was partially mediated by problems with inhibitory control measured at age 13. In another study, PCE predicted age at initiation of penetrative sex (but not oral sex); this effect was fully mediated by cannabis and alcohol use by age 15 (De Genna et al., 2014). Moving beyond initiation of sex, Min et al. (2016) examined the effect of PCE on risky sex at ages 15 or 17, controlling for age at sexual initiation and adolescent substance use. They found that adolescents with PCE were more likely to have had risky sex, defined as the use of drugs or alcohol before sex, sex without a condom or birth control at the most recent sexual encounter, 2 or more sex partners in the past month, or teen pregnancy (Min et al., 2016). To date, there have been no studies of PCE on adult sexual behavior.

In the current study, a variety of risky sexual outcomes were measured at age 25 in a prenatal cohort of individuals, about half of whom were prenatally exposed to cocaine. Participants reported on their experiences of sexual intercourse under the influence of alcohol or drugs, sex with risky partners, problems with condom use, condom use self-efficacy, and history of sexually transmitted infection (STI). This cohort has prospective assessments of prenatal substance use, family environment, and child behavior and development in the offspring at ages 1, 3, 7, 10, 15, 21, and 25, allowing us to examine pathways from PCE to risky adult sex. We hypothesized that adults with PCE would be more likely to engage in risky sexual behavior, given the association of PCE with behavioral disinhibition manifested as childhood externalizing behavior problems (Bada et al., 2012; Min et al., 2014; Minnes et al., 2010; Richardson et al., 2009; 2011; 2013a; 2015), early substance use (Frank et al., 2011; Lester et al., 2012; Min et al., 2014; Richardson et al., 2013b; 2019), and early sexual behavior (De Genna et al., 2014; Lambert et al., 2013). We considered the role of these variables in pathways from PCE to adult sexual risk because of previous research linking childhood behavior problems and experiences (Min et al., 2016) and early initiation of substance use and sex (De Genna & Cornelius, 2015; Guo et al., 2002; Staton et al., 1999) to risky sexual behavior. Based on prior work, we hypothesized that there would be indirect effects of PCE on risky sexual behavior during young adulthood via early cannabis use and early initiation of sexual intercourse in exposed individuals.

2. Methods

This is a prospective study of the long-term effects of PCE on sexual behavior in a cohort whose mothers were recruited between 1988 – 1992. The current analysis focuses on offspring who were assessed at the 25-year phase of the study (n = 202). Data from previous phases were used to delineate pathways from PCE to adult sexual behavior. The University of Pittsburgh IRB approved each phase of the study.

2.1. Sample

Recruitment methods for the parent study have been described elsewhere (Richardson et al., 2007). Briefly, pregnant women were recruited from the prenatal clinic of a university teaching hospital in Western Pennsylvania early in pregnancy (4th – 5th month of pregnancy). Approximately 40% of the selected sample used cocaine during the first trimester, with a decrease across pregnancy to 10% who used during the third trimester (Richardson et al., 1999). At birth, 295 healthy infants were assessed with their mothers and these dyads were seen again when the offspring were 1, 3, 7, 10, 15, 21, and 25 years of age. Two hundred and two offspring were seen at the 25-year phase, representing 69% of the birth sample. At 25 years of age, 93 offspring were not assessed for the following reasons: nine died prior to this assessment; two were placed for adoption earlier in life and were not eligible to be contacted; 12 were incarcerated or in a rehabilitation facility; 26 refused to participate; 23 moved out of the area; and 21 were lost to follow-up. Two of the young adult offspring did not complete the questionnaire with items on sexual behavior and 7 reported not having had sexual intercourse by this time and were removed from the sample for the current analysis.

Attrition analysis revealed no significant difference in PCE status for those who participated compared to those who did not at the 25-year follow-up. There were also no significant differences in maternal sociodemographic characteristics (education, work, marital status, race); prenatal alcohol, cannabis, or tobacco exposure; or newborn characteristics (gestational age, weight, length) between those offspring who were and were not assessed at the 25-year phase. However, offspring who participated in this phase of the study were less likely to be male than those who did not participate (45.1% vs. 69.6% male, p < .001).

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Prenatal cocaine exposure (PCE)

Mothers were interviewed about their cocaine and crack, tobacco, alcohol, cannabis, and other illicit drug use at each phase. Cocaine and crack use were reported in lines, rocks, or grams, or in cost if the woman could not report quantity. A dichotomous variable indicating any prenatal cocaine use during the first trimester was created for this analysis.

2.2.2. Risky sex outcomes

At the 25-year follow-up, offspring were asked to complete a questionnaire on health behaviors that included questions on risky sexual behavior. For the past year, participants were asked if they had engaged in sex while drunk or high on an illicit substance (0=never drunk or high, 1= sometimes drunk or high, 2= almost always/always drunk or high) and if they had experienced condom problems, if a condom broke or came off during penetrative sex (dichotomized to none versus any). Responses to lower frequency sexual behaviors and experiences indicating risky sexual partners (engaging in sex trading, rape, having a sex partner who had been in jail or prison, or having a sex partner who was an injection drug user) were combined to create a risky sex partner variable (any/none). In addition, participants were asked if a healthcare provider had ever told them they were diagnosed with a STI.

The offspring were also asked to complete the Condom Use Self-Efficacy Scale (CUSES: Brafford & Beck, 1991). The original CUSES had 28 items developed to measure self-efficacy in condom use and negotiating condom use with new sexual partners with responses on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (Strongly agree) to 5 (Strongly disagree). The measure has adequate internal consistency and discriminant validity among college student samples (Brafford & Beck, 1991; Brien et al., 1994; Forsyth et al., 1997). As with other studies of non-college students (e.g., Davis et al., 2014; Sanchez-Mendoza et al., 2020), and seeking to reduce participant burden, we chose to administer the items most pertinent to our sample. There were 13 items for female participants and 14 for male participants. The additional item for male participants asked about their concerns that a new partner would interpret condom use as a sign that they had previously had sex with other males.

2.2.3. Potential mediators

Based on the literature (De Genna et al., 2014; Frank et al., 2011; Lambert et al., 2013; Lester et al., 2012; Min et al., 2014; Richardson et al., 2013b; 2019), we tested indirect pathways between PCE and adult risky sex via childhood externalizing behavior problems, experiences of child abuse, early initiation of cannabis use, and age of sexual initiation. Childhood externalizing behavior problems were assessed by the Child Behavior Checklist completed by caregivers at the age 10 assessment (CBCL; Achenbach, 1991). Adolescents reported on previous experiences of physical and emotional abuse and neglect on the Child Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) at age 15 (Bernstein et al., 1998). Starting at the 15-year follow-up, participants were asked if they had ever used cannabis. Use by age 15 was coded as early cannabis use (dichotomous). At the 15-year and every ensuing follow-up, participants were asked if they had ever had sexual intercourse (includes vaginal or anal sex). If they responded affirmatively, they were asked how old they were the first time they had sex (in years).

2.2.4. Covariates

Prenatal exposure to other substances was calculated using quantity and frequency of cigarette, alcohol, and cannabis use reported by mothers during the first trimester assessment (Richardson et al., 2008). Sex assigned at birth was recorded at delivery (male/female). Participants reported their own race/ethnicity at age 25, and participant age was calculated using their date of birth and the date of the assessment. For family history of alcohol or drug problems, participants reported on the presence of either condition in their immediate family (parents, siblings). Childhood internalizing behavior problems at age 10 were assessed by the CBCL maternal report form (Achenbach, 1991).

2.3. Statistical analysis

The distributions of each outcome variable were examined prior to analysis. A factor analysis was conducted on the CUSES data as previous investigators have found different factors for diverse samples including college students (Brien et al., 1994), ethnically diverse college students (Barkley & Burns, 2000), and 18- to 26-year-old Columbians (Sanchez-Mendoza et al., 2020). Principal components analysis was applied to the 13 CUSES questions completed by both males and females. The number of factors was determined by eigenvalues greater than one. Rotated varimax factor loadings were used to create each factor. By convention, loadings lower than 0.25 were excluded.

We examined bivariate associations between PCE and the outcome variables prior to multivariate analysis. Regression analyses then tested for a direct effect of PCE on the risky sex outcomes, adjusting for significant covariates. Logistic regression was applied to the dichotomous outcome variables and ordinal logistic regression was applied to the categorical variables. To increase power, all regression models included sex assigned at birth and race but other covariates were tested hierarchically and included in the model only if they were significant at 0.05 alpha. Covariates were entered into the regression model in blocks: 1) Other prenatal exposures (alcohol, cannabis, and tobacco), 2) Family history of alcohol and drug problems, and 3) Childhood risk factors (internalizing behavior problems at age 10). We tested the relation between potential mediators (childhood externalizing problems, child abuse, early initiation of cannabis, age at sexual initiation) and the adult risky sex outcome variables. We retained those variables that were significantly related to the outcome variables and tested the indirect effect of PCE on risky adult sex via these mediators using structural equation modeling in Mplus (Iacobucci, 2012).

3. Results

3.1. Sample characteristics

On average, offspring (55% female, 54% Black, 46% White) were 27 years old (SD = 0.98 years, range = 25–30) at the 25-year follow-up, with an average of 13.4 years of education (SD = 1.78, range = 8–19). Only 15% were married but 38% were living with a partner. A substantial minority were still living at home with one or both parents: 5% living with father, 15% living with mother, and 10% living with both. Most (84%) of the participants were employed, 12% were enrolled in school, and 5% were serving in the military. Substance use was prevalent with 91%, 55%, 34%, and 19% of the participants reporting past month alcohol, cannabis, tobacco, and other illicit drug use, respectively. As seen in Table 1, the mothers of participants with first trimester PCE were older, more likely to be single, and used more tobacco, alcohol, cannabis, and other illicit drugs while pregnant than the mothers of participants with no first trimester PCE. However, there were few demographic differences between exposed and unexposed offspring, with exposed offspring less likely to be living with a partner than the non-exposed.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics as a function of first trimester cocaine exposure

| No cocaine use 1st trimester | Cocaine use 1st trimester | p value a | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 118 | n = 75 | ||

| First trimester maternal characteristics | |||

| Black (%) | 43.2 | 53.3 | n.s. |

| Age (yrs) (mean, SD) | 24.3 (4.8) | 26.1 (5.1) | 0.01 |

| Education (yrs) (mean, SD) | 12.1 (1.4) | 11.9 (1.2) | n.s. |

| Family income ($/mo) (mean, SD) | 757.2 (614) | 654 (748) | n.s. |

| Single (%) | 72.9 | 88.0 | 0.01 |

| Cigarettes/day (mean, SD) | 6.1 (9.4) | 10.7 (9.2) | 0.001 |

| Drinks/day (mean, SD) | 0.25 (0.6) | 1.96 (2.7) | 0.001 |

| Joints/day (mean, SD) | 0.06 (0.2) | 0.48 (1.2) | 0.001 |

| Other illicit drugs (not including cocaine or cannabis use) (%) | 2.5 | 10.7 | 0.02 |

| 25-year offspring characteristics | |||

| Age (yrs) (mean, SD) | 27.4 (1.1) | 27.1 (0.8) | n.s. |

| Male (%) | 49.1 | 38.7 | n.s. |

| Black (%) | 49.2 | 62.7 | 0.07 |

| Education (yrs) (mean, SD) | 13.5 (1.7) | 13.3 (1.9) | n.s. |

| Working (% yes) | 82.2 | 86.7 | n.s. |

| Attend school (% yes) | 12.7 | 10.7 | n.s. |

| Personal income ($/mo) (mean, SD) | 2038 (1872) | 1717 (1276) | n.s. |

| Receive public assistance (% yes) | 3.4 | 4.0 | n.s. |

| Live with partner (%) | 44.1 | 29.3 | 0.04 |

| ≥ 1 child (%) | 45.8 | 50.7 | n.s. |

Based on a t-test or Mann-Whitney test for continuous variables and on a Chi-square test of differences for dichotomous variables.

3.2. Prevalence of risky sexual behavior outcomes

The most common risky sexual behavior was sex while drunk or high in the past year (63%). Nearly one third reported that they sometimes had sex while drunk or high, and another third reported that they almost always had sex while drunk or high. One-quarter of the sample reported having had a risky sexual partner, 15% reported that a condom had broken or come off during penetrative sex, and 39% had a history of STI.

3.3. Condom use self-efficacy

As seen in Table 2, three CUSES factors were identified by the factor analysis These factors reflected: (1) confidence suggesting condom use with a new partner (even if unsure about their feelings about condoms, not afraid of rejection, not worried they would think I had an STI or that I thought they had an STI); (2) confidence in correct condom use during sex while under the influence (of alcohol or drugs) or heat of passion; and (3) confidence in their condom use skills (putting on a condom, using a condom correctly, ability to put on a condom quickly). The variance explained by these factors was 3.1%, 2.9%, and 2.3%, respectively.

Table 2.

Rotated Varimax Factor loadings for CUSES

| Factor 1 Condoms with a New Partner | Factor 2 Passion/Under the Influence | Factor 3 Condom Skills | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Confident in ability to put on a condom | 0.05037 | 0.07643 | 0.84430 |

| 2. Confident in ability to discuss condom use with any partner | 0.45516 | 0.46446 | 0.34290 |

| 3. Confident in ability to suggest using condoms with new partner | 0.47391 | 0.52664 | 0.31467 |

| 4. Confident suggesting without partner feeling ‘diseased’ | 0.47363 | 0.34987 | 0.27938 |

| 5. Not afraid my partner would reject me for suggesting it | 0.73047 | 0.02434 | −0.04883 |

| 6. Would suggest it even if I were unsure about partner’s feelings | 0.69326 | 0.26444 | −0.01863 |

| 7. Confident in my ability to use a condom correctly | 0.24028 | 0.23673 | 0.71847 |

| 8. Not afraid my partner might think I have an STD | 0.84024 | 0.09064 | 0.19606 |

| 9. Not afraid my partner might think they have an STD | 0.78868 | 0.11439 | 0.21387 |

| 10. Confident in my ability to put on a condom quickly | 0.04911 | 0.22870 | 0.79273 |

| 11. Confident I would remember to use even after drinking | 0.14799 | 0.87447 | 0.18629 |

| 12. Confident I would remember to use even if I was high | −0.00368 | 0.81507 | 0.22033 |

| 13. Confident I would remember to use in the heat of passion | 0.24242 | 0.78012 | 0.06646 |

3.4. Bivariate associations between PCE and adult risky sex

First trimester PCE was significantly associated with having sex while drunk or high, problems with condom use, and the CUSES factor related to condom use skills (Table 3). PCE was not associated with the other CUSES factors or the other risky sex outcomes. Individuals with PCE were more likely to report a history of child abuse, initiate cannabis use by age 15, and have sex at an earlier age. However, child abuse was not associated with the risky sex outcomes in this sample. Thus, early cannabis use and age of sexual initiation were considered as possible mediators in multivariate analysis.

Table 3.

Risky sex outcomes and potential mediators as a function of first trimester cocaine exposure

| No cocaine use 1st trimester | Cocaine use 1st trimester | p value a | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 118 | n = 75 | ||

| Sex while drunk/high | |||

| No, % (n) | 46.1 (54) | 22.7 (17) | |

| Sometimes, % (n) | 30.8 (36) | 32.0 (24) | |

| Almost always/always, % (n) | 23.1 (27) | 45.3 (34) | 0.001 |

| Problems with condom use, % (n) | 11.1 (13) | 21.3 (16) | 0.05 |

| Risky sex partner, % (n) | 20.3 (24) | 32.0 (24) | 0.07 |

| CUSESb - Confidence suggesting condom use to new partner, mean (SD) | 5.9 (2.3) | 6.3 (2.2) | n.s. |

| CUSESb -Confidence using condom correctly in the heat of passion/under the influence, mean (SD) | 6.2 (2.6) | 6.2 (2.6) | n.s. |

| CUSESb - Condom use skills, mean (SD) | 4.3 (1.6) | 4.8 (1.8) | 0.03 |

| Externalizing behavior problem scores at age 10 (CBCL) | 50.3 (11.7) | 49.2 (10.4) | 0.53 |

| Child abuse (CTQ) measured at age 15 | 1.97 (0.5) | 2.27 (0.9) | 0.01 |

| Early initiation of cannabis (% < 15 yrs) (n) | 19.5 (23) | 46.7 (35) | 0.0001 |

| Average age of sexual initiation (yrs) | 16.2 | 15.3 | 0.02 |

Based on t-test or Mann-Whitney for continuous variables and on Chi-square test for dichotomous/categorical variables.

Higher scores indicate less confidence and skill

3.5. Regression analyses testing for direct effects

PCE was a significant predictor of sex while drunk/high (Cumulative Odds Ratio (COR) =2.35, p< .01), controlling for sex assigned at birth, race, and family history of alcohol problems (Table 4). This effect remained significant after inclusion of early initiation of cannabis use and of sex (COR = 1.84, p< .05). The condom skills variable was highly skewed so it was dichotomized to the upper quartile (versus all others) and analyzed using logistic regression. PCE was marginally related to condom use skills (Odds Ratio = 2.03, p= < .056). This relation was significant after inclusion of early initiation of cannabis use and sex (Odds Ratio = 2.13, p <.05). There were no direct effects of PCE on any other adult risky sexual outcome variables.

Table 4.

Results of final regression models testing the direct effects of first trimester cocaine exposure (PCE) on adult risky sex and history of STI

| Predictors | Regression coefficient | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex while drunk/high | Cumulative Odds Ratio | |||

| Without mediators | ||||

| Sex assigned at birth | 0.44 | 1.56 | 0.11 | |

| Race | −0.12 | 0.88 | 0.65 | |

| Family history of alcohol abuse | 0.75 | 2.12 | 0.01 | |

| First trimester PCE | 0.86 | 2.35 | 0.004 | |

| With mediators included1 | ||||

| Sex assigned at birth | 0.41 | 1.51 | 0.15 | |

| Race | −0.05 | 0.95 | 0.86 | |

| Family history of alcohol abuse | 0.71 | 2.04 | 0.02 | |

| Early cannabis use | 0.80 | 2.23 | 0.02 | |

| Age at sexual initiation | −0.12 | 0.88 | 0.04 | |

| First trimester PCE | 0.61 | 1.84 | 0.05 | |

| Condom Problems | Odds Ratio | |||

| Without mediator | ||||

| Sex assigned at birth | 0.33 | 1.39 | 0.44 | |

| Race | −1.47 | 0.23 | 0.005 | |

| Prenatal tobacco exposure | 0.07 | 1.07 | 0.004 | |

| First trimester PCE | 0.42 | 1.52 | 0.34 | |

| With mediators included1 | ||||

| Sex assigned at birth | 0.36 | 1.43 | 0.42 | |

| Race | −1.56 | 0.21 | 0.004 | |

| Prenatal tobacco exposure | 0.07 | 1.07 | 0.003 | |

| Early cannabis use | −0.66 | 0.52 | 0.23 | |

| Age at sexual initiation | −0.10 | 0.91 | 0.29 | |

| First trimester PCE | 0.54 | 1.71 | 0.23 | |

| Risky sex partners | Odds Ratio | |||

| Without mediators | ||||

| Sex assigned at birth | −0.37 | 0.67 | 0.30 | |

| Race | −0.52 | 0.60 | 0.16 | |

| Family history of drug abuse | 1.02 | 2.78 | 0.005 | |

| First trimester PCE | 0.35 | 1.42 | 0.32 | |

| With mediators included1 | ||||

| Sex assigned at birth | −0.33 | 0.72 | 0.37 | |

| Race | −0.56 | 0.57 | 0.14 | |

| Family history of drug abuse | 1.10 | 3.0 | 0.004 | |

| Early cannabis use | −0.70 | 0.50 | 0.11 | |

| Age of sexual initiation | −0.16 | 0.85 | 0.05 | |

| First trimester PCE | 0.42 | 1.53 | 0.25 | |

| Condom skills | Odds Ratio | |||

| Without mediators | ||||

| Sex assigned at birth | −0.80 | 0.45 | 0.03 | |

| Race | 0.28 | 1.32 | 0.44 | |

| Family history of alcohol abuse | 0.91 | 2.48 | 0.01 | |

| First trimester PCE | 0.71 | 2.03 | 0.056 | |

| With mediators included1 | ||||

| Sex assigned at birth | −0.80 | 0.45 | 0.03 | |

| Race | 0.26 | 1.30 | 0.46 | |

| Family history of alcohol abuse | 0.93 | 2.54 | 0.01 | |

| Early cannabis use | −0.18 | 0.83 | 0.68 | |

| Age of sexual initiation | 0.01 | 1.01 | 0.86 | |

| First trimester PCE | 0.76 | 2.13 | 0.05 | |

| History of STI | Odds Ratio | |||

| Without mediators | ||||

| Sex assigned at birth | −1.25 | 0.29 | 0.001 | |

| Race | −1.80 | 0.17 | 0.001 | |

| Family history of alcohol abuse | 0.78 | 2.19 | 0.03 | |

| First trimester PCE | −0.09 | 0.92 | 0.82 | |

| With mediators included1 | ||||

| Sex assigned at birth | −1.43 | 0.24 | 0.0002 | |

| Race | −1.86 | 0.16 | 0.0001 | |

| Family history of alcohol abuse | 0.71 | 2.03 | 0.06 | |

| Early cannabis use | 0.66 | 1.94 | 0.13 | |

| Age of sexual initiation | −0.18 | 0.83 | 0.03 | |

| First trimester PCE | −0.36 | 0.70 | 0.36 |

Effects of PCE with mediators (cannabis use by age 15 and age at first sexual intercourse) and significant covariates from previous model included

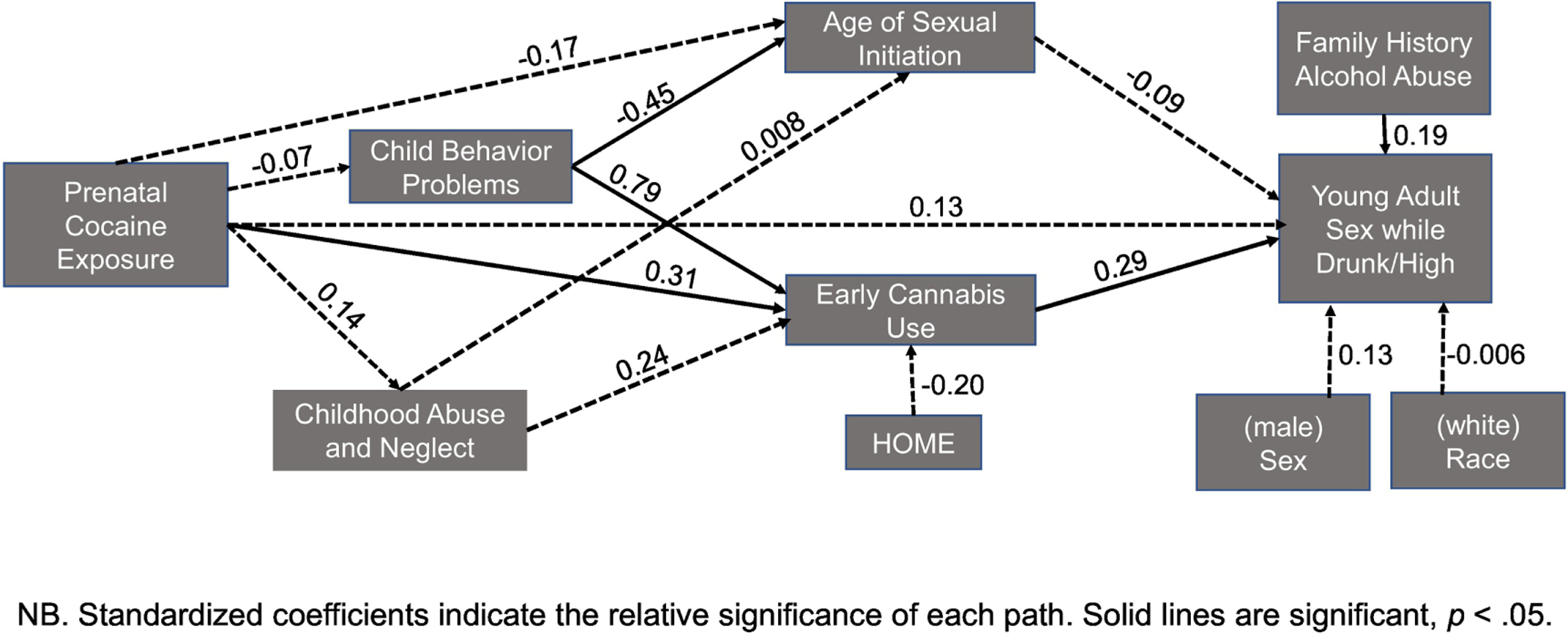

3.6. Structural equation modeling of indirect effects

Child externalizing behavior problems and child abuse were not significantly related to the adult risky sex outcomes and were thus not tested as mediators. Age of sexual initiation was significantly related to the following adult risky sex outcomes: sex while drunk/high (mean ages 16.5, 16.1, 14.9 years, for no, sometimes, always, respectively, p < 0.001), risky sex partners (mean age 16.1 for none versus 15.2 for risky sex partners, p < 0.05), and STI history (mean age 16.4 for none versus 15.1 for history of STI, p < 0.001). Early initiation of cannabis use was significantly related to sex while drunk/high (15.5%, 26.7%, and 50.8% for no, sometimes, and always, respectively, p< 0.0001) and STI (21.4% with no STI history versus 43.4% among those with STI history, p=0.001). Therefore, the indirect pathways from PCE to these outcome variables via these possible mediators were tested using structural equation modeling. The full path model for PCE and sex while drunk/high is shown in Figure 1. The total indirect effect of PCE on sex while drunk/high via early cannabis initiation was significant (coefficient= 0.22, p = 0.02), whereas the direct effect between PCE and sex while drunk/high was no longer significant. The indirect effect between PCE and STI via early cannabis initiation was also significant (coefficient = 0.33, p =0.02). No other indirect effects were found to be significant.

Figure 1.

Pathways from prenatal cocaine exposure to adult sex while drunk or high

4. Discussion

This study expands on prior research demonstrating the long-term effects of PCE on behavior, consistent with a behavioral teratology framework, with dysregulation manifesting as externalizing behavior problems, Conduct Disorder, earlier initiation of substance use and sex, and arrests (Richardson et al., 2019). Min et al. (2016) demonstrated that adolescents with PCE were more likely to engage in risky sexual behavior (substance use before sex, not using condoms or birth control, multiple sex partners) or experience teen pregnancy (Min et al., 2016), and we have previously demonstrated that PCE predicted age at initiation of penetrative sex (De Genna et al., 2014). We extend that work by showing that individuals with PCE may engage in some risky sexual behavior as adults, including sex under the influence of alcohol and/or drugs. This is consistent with other findings in this cohort relating PCE to histories of Conduct Disorder and arrests by age 21 (Richardson et al., 2019). However, exposed adults were not more likely to report an STI diagnosis compared to unexposed adults. The results of the current analysis are relevant to the PCE literature as they continue to document long-term associations between PCE and behavior.

The results of this study highlight the importance of the association between PCE and adolescent risk behavior for persistent effects of PCE on other outcomes. In a prior study, the effect of PCE on age of initiation of sexual intercourse was fully mediated by early use of alcohol and cannabis (De Genna et al., 2014). Similarly, Richardson et al. (2019) found that early initiation of cannabis use mediated the effects of PCE on cannabis use at age 21. In this study, early initiation of cannabis use partially mediated the effect of PCE on adult sex under the influence of alcohol or drugs. As with the gestational period, adolescence represents a key period for exposure to drugs of abuse that has important implications for human development and potential intervention points. By contrast, early initiation of cannabis did not mediate the effect of PCE on condom use skills. Similarly, Min et al. (2016) found a direct effect of PCE on alcohol or drug use before sex, not using a condom, not using birth control at most recent sexual encounter, 2 or more sex partners in the past month, or having experienced a teen pregnancy by ages 15 or 17. These adolescent sexual behaviors and outcomes are arguably less common and riskier than some of the adult behaviors and outcomes measured in the current study in offspring who were, on average, in their late twenties. By this age, the effect of PCE appears to have been mostly mediated by variables measured during adolescence, including age of sexual initiation and early cannabis use. These findings have clinical implications for individuals with PCE, indicating that they are not only at greater risk of early initiation of cannabis, but that this early cannabis use places them at ongoing behavioral risk, and provides a potential time point for earlier intervention.

We did not find sex differences in the associations between PCE and risky sexual behavior or STI. Other investigators have reported stronger effects of PCE for male offspring (Kestler et al., 2012). For example, Allen and colleagues (2014) reported that adolescent boys with PCE had the greatest propensity to take risk but adolescent girls with PCE were less likely to take risks than unexposed girls and than any of the boys. Min et al. (2015) found that the effect of PCE on early sex in girls was mediated by age 12 externalizing behavior but did not find a mediating effect in boys with PCE. In the current study, females reported less condom skill efficacy and were more likely to have been diagnosed with an STI than males, but there were no sex differences in the effects of PCE on any of the adult risky sex outcomes in multivariate analysis that included mediators. Similarly, most of the sex differences seen in bivariate analyses at age 21 in this cohort did not remain significant in multivariate models (Richardson et al., 2019). It is important to investigate sex differences in the effects of prenatal exposures and report the findings, even if they are null, to advance the science in this area (Levin et al., 2021).

The results of this study should be interpreted with caution given several important limitations. Self-reported sexual behavior is subject to social desirability bias, although this may be less likely with anonymous surveys and in a study where individuals have had the opportunity to build rapport with study staff over two decades. There are also concerns about self-report for STI because individuals with asymptomatic infections may not realize that they are infected. However, biological tests only capture active infections and not the history of STI that individuals may have experienced to date. The study also focused on first trimester cocaine use, which was the most prevalent. Maternal cocaine use was measured at each trimester, consistent with the behavioral teratologic model and the identification of critical periods (Vorhees, 1989). However, all women who reported second and third trimester cocaine use also used cocaine during the first trimester of pregnancy. This study provides converging data linking first trimester exposure to long-term behavioral outcomes (e.g., De Genna et al., 2014; Richardson et al., 2019).

The sample was primarily Black or White and urban, and therefore results may not generalize to rural young adults and those from other racial/ethnic backgrounds. Additionally, fewer males were tested at this follow-up, raising concerns about generalizability and statistical power. Nonetheless, sex assigned at birth was associated with the adult sex outcomes, indicating sufficient power to test for sex differences in the current study. In the multivariate models, male sex was linked to problems with condom use (coming off or breaking during sex), whereas female sex was associated with history of STI. Nonetheless, differential attrition of males may limit the generalizability of results for males exposed to PCE.

Attrition is a challenge facing all longitudinal studies of high-risk populations and this sample was considerably smaller 25+ years after mothers were enrolled in the study. This may have resulted in limited power to test for the effects of PCE on adult risky sexual behavior and outcomes, while controlling for covariates from different developmental phases including prenatal, childhood, adolescent, and adult assessment phases. Given the rates of PCE, risky sex partners, and history of STI in our sample, we had enough power to detect medium effect sizes for the risky sex partner and STI outcomes, but lacked the power to detect smaller effect sizes. We adopted the following analytic strategy to mitigate the smaller sample size in this study: Potential covariates were selected based on the literature and tested hierarchically prior to inclusion in the regressions to test the most parsimonious models.

The study also had numerous strengths including a breadth of data spanning 25+ years on individuals born at the same hospital who were and were not exposed to cocaine in utero, detailed assessment of prenatal and postpartum drug exposure, and careful assessment of covariates, which allowed for a better understanding of the effects of PCE on adult risky sex in the context of their prenatal, childhood, adolescent, and adult environments. According to behavioral teratological principles, it is crucial to carefully measure the environment at each stage of development to tease apart the effects of PCE from effects of the environment associated with maternal drug use.

Conclusions

As one of the only prospective cohort studies to follow exposed individuals into adulthood and carefully measure a wide range of covariates and outcomes, analysis of adult functioning in this cohort as a function of PCE is highly relevant to the literature. Overall, there were few differences between individuals who were and were not prenatally cocaine-exposed by the time the cohort reached their mid-twenties. Exposed individuals had similar levels of education and employment and were not more likely to have had children or received public assistance. In terms of sexual risk, they were not more likely to have had risky sexual partners or a history of STI. However, PCE offspring were less likely to currently be living with a romantic partner and less confident in their abilities to use condoms, use them correctly, or put them on quickly. There was also an indirect effect of PCE on sex under the influence of drugs and alcohol that was mediated through early initiation of cannabis use and sexual intercourse. These findings demonstrate the continuity of long-term effects from PCE related to adolescent risk behavior seen in this cohort at age 21 (Richardson et al., 2019) and highlight adolescence as a key period of vulnerability for exposed individuals. Thus, there appear to be some long-term effects of PCE on sexual behavior that reach into adulthood, although risk can be detected in individuals as early as mid-adolescence when exposed individuals are more likely to initiate early substance use and early sex.

Highlights.

Prenatal cocaine exposure indirectly linked to adult sex while drunk or high.

Early cannabis use mediated the effect of prenatal cocaine exposure on adult sex.

Adults with prenatal cocaine exposure were not more likely to have a STI.

Role of Funding Source

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (DA008916, PI; Richardson). The NIH had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript, or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest

No conflicts to declare.

References

- Achenbach TM, Edelbrock C, 1991. Child behavior checklist 7, 371–392, Burlington, VT. [Google Scholar]

- Allen JW, Bennett DS, Carmody DP, Wang Y, Lewis M, 2014. Adolescent risk-taking as a function of prenatal cocaine exposure and biological sex. Neurotox. Teratol 41, 65–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bada HS, Bann CM, Whitaker TM, Bauer CR, Shankaran S, LaGasse L, Lester BM, Hammond J, Higgins R, 2012. Protective factors can mitigate behavior problems after prenatal cocaine and other drug exposures. Pediatrics 130, e1479–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandstra ES, Accornero VH, Vidot DC, Mansoor E, Xue L, Morrow C, Anthony J, 2015. Cocaine use in late adolescence: Impact of prenatal cocaine exposure, sex/gender, and ongoing caregiver cocaine use. Drug Alcohol Depend 146, e216. [Google Scholar]

- Barkley TW Jr., Burns JL, 2000. Factor analysis of the Condom Use Self-Efficacy Scale among multicultural college students. Health Edu. Res 15, 485–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett DS, Lewis M, 2020. Does prenatal cocaine exposure predict adolescent substance use? Neurotox. Teratol 81, 106906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Fink L, Handelsman L, Foote J, 1998. Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Assessment of Family Violence: A Handbook for Researchers and Practitioners

- Brafford LJ, Beck KH, 1991. Development and validation of a condom self-efficacy scale for college students. J. Am. Coll. Health 39, 219–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brien TM, Thombs DL, Mahoney CA, Wallnau L, 1994. Dimensions of self-efficacy among three distinct groups of condom users. J. Am. Coll. Health 42, 167–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis KC, Masters NT, Eakins D, Danube CL, George WH, Norris J, Heiman JR, 2014. Alcohol intoxication and condom use self-efficacy effects on women’s condom use intentions. Addict. Behav 39,153–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Genna NM, Cornelius MD, 2015. Maternal drinking and risky sexual behavior in offspring. Health Educ. Behav 42, 185–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Genna NM, Goldschmidt L, Richardson GA, 2014. Prenatal cocaine exposure and age of sexual initiation: Direct and indirect effects. Drug Alc. Depend 145, 194–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forman LS, Liebschutz JM, Rose-Jacobs R, Richardson MA, Cabral HJ, Heeren TC, Frank DA, 2017. Urban young adults‟ adaptive functioning: Is there an association with history of prenatal exposure to cocaine and other substances? J. Drug Iss 47, 261–276. [Google Scholar]

- Forsyth AD, Carey MP, Fuqua RW, 1997. Evaluation of the validity of the ondom Use Self-Efficacy Scale (CUSES) in young men using two behavioral simulations. Health Psychol 16, 175–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank DA, Kuranz S, Appugliese D, Cabral H, Chen C, Crooks D, Rose-Jacobs R, 2014. Problematic substance use in urban adolescents: Role of intrauterine exposures to cocaine and marijuana and post-natal environment. Drug Alcohol Depend 142, 181–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank DA, Rose-Jacobs R, Crooks D, Cabral HJ, Gerteis J, Hacker KA, Heeren T, 2011. Adolescent initiation of licit and illicit substance use: Impact of intrauterine exposures and post-natal exposure to violence. Neurotoxicol. Teratol 33,100–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo J, Chung IJ, Hill KG, Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Abbott RD, 2002. Developmental relationships between adolescent substance use and risky sexual behavior in young adulthood. J. Adolesc. Health 31, 354–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacobucci D, 2012. Mediation analysis and categorical variables: The final frontier, J. Consumer Psychol 22, 582–594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kestler L, Bennett DS, Carmody DP, Lewis M, 2012. Gender-dependent effects of prenatal cocaine exposure, in Lewis M, Kestler L, (Eds.), Decade of Behavior. Gender Differences in Prenatal Substance Exposure American Psychological Association, pp. 11–29. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert BL, Bann CM, Bauer CR, Shankaran S, Bada HS, Lester BM, Whitaker TM, LaGasse LL, Hammond J, Higgins RD, 2013. Risk-taking behavior among adolescents with prenatal drug exposure and extrauterine environmental adversity. J. Dev. Behav. Ped 34, 669–679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lester BM, Lin H, DeGarmo DS, Fisher PA, LaGasse LL, Levine TP, Hammond JA, 2012. Neurobehavioral disinhibition predicts initiation of substance use in children with prenatal cocaine exposure. Drug Alcohol Depend 126, 80–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin ED, Dow-Edwards D, Patisaul H, 2021. Introduction to sex differences in neurotoxic effects. Neurotox. Teratol 83, 106931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min MO, Minnes S, Lang A, Albert JM, Kim JY, Singer LT, 2016. Pathways to adolescent sexual risk behaviors: Effects of prenatal cocaine exposure. Drug Alcohol Depend 161, 284–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min MO, Minnes S, Lang A, Weishampel P, Short EJ, Yoon S, Singer LT, 2014. Externalizing behavior and substance use related problems at 15 years in prenatally cocaine exposed adolescents. J. Adolesc 37, 269–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min MO, Minnes S, Lang A, Yoon S, Singer LT, 2015. Effects of prenatal cocaine exposure on early sexual behavior: Gender difference in externalizing behavior as a mediator. Drug Alcohol Depend 153, 59–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min MO, Minnes S, Park H, Ridenour T, Kim JY, Yoon M, Singer LT, 2018. Developmental trajectories of externalizing behavior from ages 4 to 12: Prenatal cocaine exposure and adolescent correlates. Drug Alcohol Depend 192, 223–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minnes S, Min MO, Kim J-Y, Francis MW, Lang A, Wu M, Singer LT, 2017. The association of prenatal cocaine exposure, externalizing behavior and adolescent substance use. Drug Alcohol Depend 176, 33–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minnes S, Singer LT, Kirchner HL, Short E, Lewis B, Satayathum S, Queh D, 2010. The effects of prenatal cocaine exposure on problem behavior in children 4–10 years. Neurotox. Teratol 32, 443–451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minnes S, Singer L, Min MO, Wu M, Lang A, Yoon S, 2014. Effects of prenatal cocaine/polydrug exposure on substance use by age 15. Drug Alcohol Depend 134, 201–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson GA, De Genna NM, Goldschmidt L, Larkby C, Donovan JE, 2019. Prenatal cocaine exposure: Direct and indirect associations with 21-year-old offspring substance use and behavior problems. Drug Alcohol Depend 195, 121–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson GA, Goldschmidt L, Larkby C, 2007. Effects of prenatal cocaine exposure on growth: A longitudinal analysis. Pediatrics 120, e1017–e1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson GA, Goldschmidt L, Larkby C, Day NL, 2013a. Effects of prenatal cocaine exposure on child behavior and growth at 10 years of age. Neurotox. Teratol 40, 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson GA, Goldschmidt L, Larkby C, Day NL, 2015. Effects of prenatal cocaine exposure on adolescent development. Neurotox. Teratol 49, 41–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson GA, Goldschmidt L, Leech S, Willford J, 2011. Prenatal cocaine exposure: Effects on mother-and teacher-rated behavior problems and growth in school-age children. Neurotox. Teratol 33, 69–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson GA, Goldschmidt L, Willford J, 2008. The effects of prenatal cocaine use on infant development. Neurotoxicology and teratology, 30(2), 96–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson GA, Goldschmidt L, Willford J, 2009. Continued effects of prenatal cocaine use: Preschool development. Neurotox.Teratol 31, 325–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson GA, Hamel SC, Goldschmidt L, Day NL, 1999. Growth of infants prenatally exposed to cocaine/crack: Comparison of a prenatal care and a no prenatal care sample. Pediatrics 104: 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson GA, Larkby C, Goldschmidt L, Day NL, 2013b. Adolescent initiation of drug use: Effects of prenatal cocaine exposure. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 52, 37–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Mendoza V, Soriano-Ayala E, Vallejo-Medina P, 2020. Psychometric properties of the Condom Use Self-Efficacy Scale among young Colombians. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17, 3762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staton M, Leukefeld C, Logan TK, Zimmerman R, Lynam D, Milich R, Martin C, Mc Clanahan K, Clayton R, 1999. Risky sex behavior and substance use among young adults. Health Soc. Work 24, 147–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vorhees CV, 1989., Concepts in teratology and developmental toxicology derived from animal research. In Hutchings DE (Ed.), Prenatal abuse of licit and illicit drugs Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 562, 31–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]