Key Points

Question

Does a multicomponent vaccine campaign increase COVID-19 vaccination rates among residents and staff in skilled nursing facilities (SNFs)?

Findings

In this randomized clinical trial of 133 SNFs that included 7496 residents and 17 963 staff, 81.1% of residents and 53.7% of staff were vaccinated. The 3-month-long campaign leveraged best practices for encouraging vaccination such as identifying frontline champions and giving small gifts to vaccinated staff; there was no significant difference in resident or staff vaccination in facilities that received the vaccine campaign vs usual care.

Meaning

Multicomponent interventions offered as a bundle may not be enough to increase COVID-19 vaccine rates in the SNF setting.

Abstract

Importance

Identifying successful strategies to increase COVID-19 vaccination among skilled nursing facility (SNF) residents and staff is integral to preventing future outbreaks in a continually overwhelmed system.

Objective

To determine whether a multicomponent vaccine campaign would increase vaccine rates among SNF residents and staff.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This was a cluster randomized trial with a rapid timeline (December 2020-March 2021) coinciding with the Pharmacy Partnership Program (PPP). It included 133 SNFs in 4 health care systems across 16 states: 63 and 70 facilities in the intervention and control arms, respectively, and participants included 7496 long-stay residents (>100 days) and 17 963 staff.

Interventions

Multicomponent interventions were introduced at the facility level that included: (1) educational material and electronic messaging for staff; (2) town hall meetings with frontline staff (nurses, nurse aides, dietary, housekeeping); (3) messaging from community leaders; (4) gifts (eg, T-shirts) with socially concerned messaging; (5) use of a specialist to facilitate consent with residents’ proxies; and (6) funds for additional COVID-19 testing of staff/residents.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcomes of this study were the proportion of residents (from electronic medical records) and staff (from facility logs) who received a COVID-19 vaccine (any), examined as 2 separate outcomes. Mixed-effects generalized linear models with a binomial distribution were used to compare outcomes between arms, using intent-to-treat approach. Race was examined as an effect modifier in the resident outcome model.

Results

Most facilities were for-profit (95; 71.4%), and 1973 (26.3%) of residents were Black. Among residents, 82.5% (95% CI, 81.2%-83.7%) were vaccinated in the intervention arm, compared with 79.8% (95% CI, 78.5%-81.0%) in the usual care arm (marginal difference 0.8%; 95% CI, −1.9% to 3.7%). Among staff, 49.5% (95% CI, 48.4%-50.6%) were vaccinated in the intervention arm, compared with 47.9% (95% CI, 46.9%-48.9%) in usual care arm (marginal difference: −0.4%; 95% CI, −4.2% to 3.1%). There was no association of race with the outcome among residents.

Conclusions and Relevance

A multicomponent vaccine campaign did not have a significant effect on vaccination rates among SNF residents or staff. Among residents, vaccination rates were high. However, half the staff remained unvaccinated despite these efforts. Vaccination campaigns to target SNF staff will likely need to use additional approaches.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04732819

This study assesses whether a multicomponent vaccine campaign increases vaccination rates among residents and staff of skilled nursing facilities.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has been especially challenging for skilled nursing facility (SNF) residents and staff. As of June 2021, SNF residents and staff accounted for 4% of COVID-19 cases and 31% of deaths in the US, while representing just 1% of the population.1,2,3,4 Aside from this shocking mortality rate, the pandemic has caused immense emotional distress among residents owing to compulsory isolation.5 Staff at SNFs, who are often disadvantaged and low-income workers,6 have endured intense clinical demands and scrutiny throughout the pandemic. Fortunately, the COVID-19 vaccines have proved highly effective in preventing severe COVID-19 disease, even among patients in SNFs.7,8,9 Further, these vaccines are safe, with low rates of serious adverse events in community dwellers and SNF residents.10,11 It is critical that a sizeable proportion of SNF residents and staff are vaccinated against COVID-19 to prevent future outbreaks and deaths.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) established the Pharmacy Partnership for Long-Term Care Program (PPP) to provide vaccination for long-stay residents and staff in more than 12 000 facilities nationwide between December 2020 and March 2021.12 Because most SNFs were unable to manage the cold-chain storage requirements of the available mRNA vaccines, facilities received 3 on-site visits from a pharmacy to fully vaccinate all residents and staff. Following the first visit, a median of 77.8% of residents were vaccinated, while the median staff vaccination rate was just 37.5%.13 Reasons for refusal to accept vaccination within SNFs are multifactorial and include concerns about the speed of the vaccines’ development, adverse effects, and distrust of government and pharmaceutical companies, with Black and Latino staff expressing more reluctance than White staff.14

Anticipating the urgent need to encourage COVID-19 vaccination, we rapidly developed a campaign targeting SNF staff and patients/proxies to be implemented during the PPP. The intervention included adaptation of evidence-based strategies used to improve influenza vaccination among health care workers, and successful strategies for implementing complex interventions in the SNF setting. We then conducted a randomized clinical trial across 4 SNF health care systems (HCS) to determine the effect of the present study intervention vs usual care on vaccine rates among SNF residents and staff.

Methods

This study was approved by Advarra’s Institutional Review Board with a waiver of individual informed consent. The trial protocol is presented in Supplement 1.

Facilities and Randomization

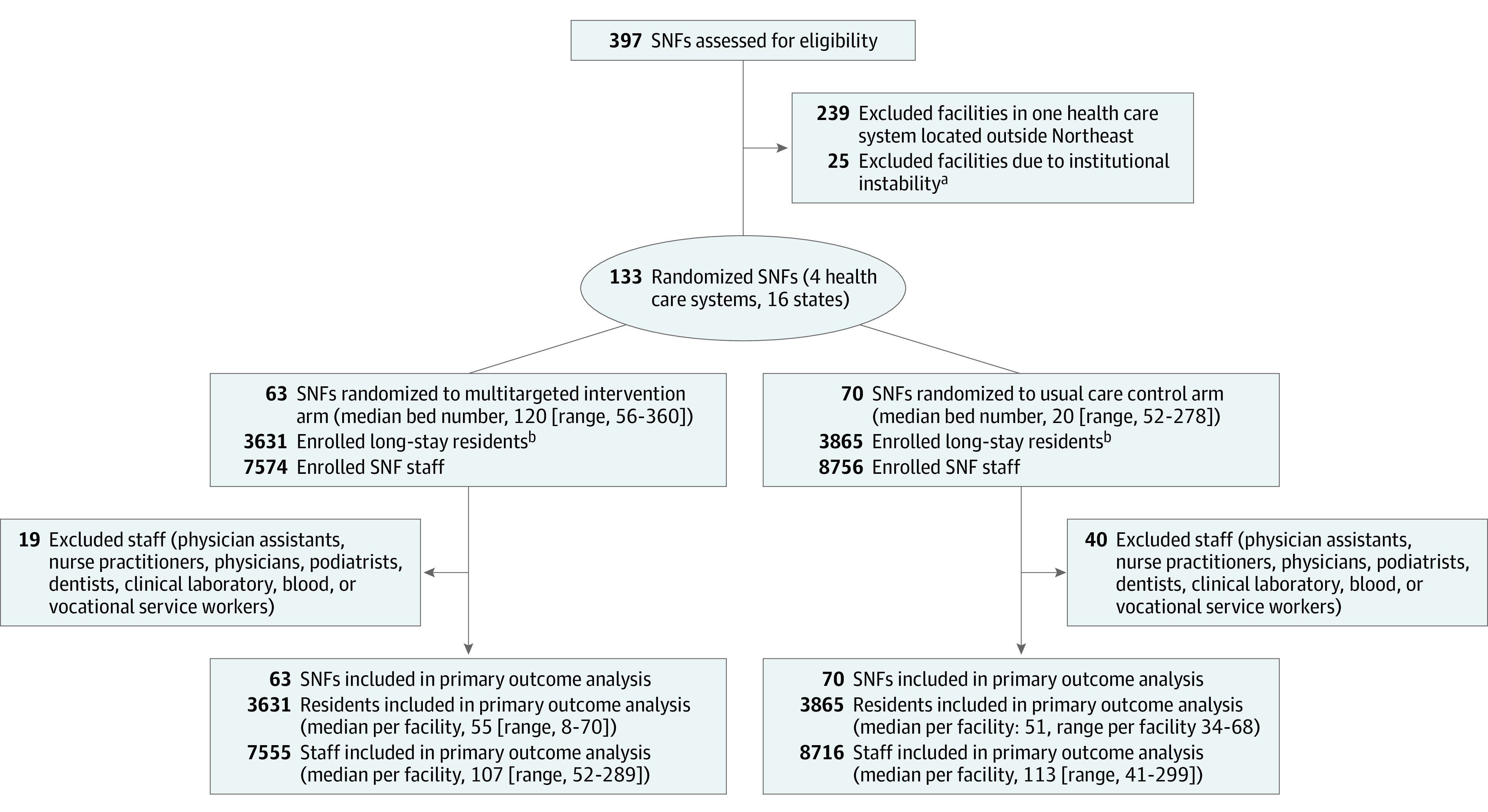

This cluster randomized clinical trial was conducted between December 2021 and March 2021 in 4 SNF HCS participating in the PPP. Because facilities with large minority populations have historically achieved low rates of influenza vaccination,15,16 we ensured facilities with large Black patient populations were included by recruiting 3 health care systems with a majority of facilities that exceeded the national median composition of Black residents. In total, the HCS owned 397 facilities distributed as follows: HCS1, n = 283; HCS2, n = 48; HCS3, n = 38; HCS4, n = 28. For HCS1, we restricted eligibility to facilities located in the Northeast (n = 44), and in all HCS, we excluded facilities with institutional instability as determined by corporate leadership (n = 25; Figure) Among the remaining 133 facilities, the study statistician used R software to select a randomization scheme stratified first by HCS and then by the proportion of Black residents in each facility as defined by the Minimum Data Set and categorized in 3 groups: less than 25%, 25% to 40%, greater than 40%. The research implementation team was not masked to assignment. The statistician was provided a data set with treatment assignment masked during analysis of the primary end points.

Figure. CONSORT Diagram Describing Selection of Intervention and Usual Care Facilities, Residents, and Staff in the IMPACT-C Trial.

SNF indicates skilled nursing facility.

aInstitutional instability was defined by asking the leaders of the 4 health care systems to identify any facilities that were likely to be divested within the next 3 months.

bLong stay indicates a nursing home stay that was greater than or equal to 100 days as of the date of the first vaccine clinic.

Participants

Participants included all long-stay residents and staff in the randomized facilities. Long-stay was defined as residing in the facility for 100 days or longer at the time of the first vaccine clinic. Staff were individuals who provided care anywhere in the facility at the time of the first vaccine clinic. We estimated the number of staff retrospectively using the Staffing Data Submission Payroll Based Journal (PBJ)17: the total unique staff working in the facility during the 8 weeks before the first vaccine clinic, by discipline. Staff disciplines that typically provide care in multiple facilities (eg, dentist, physician) were excluded (n = 59; Figure).

Intervention

Based on our team’s experience with complex intervention studies in SNFs and prior literature on strategies to increase influenza vaccination in health care workers, we planned a multicomponent intervention to encourage COVID-19 vaccination. The components of the intervention were intended to address misinformation via education from trusted sources, and to garner positive emotions as motivators for vaccination. The intervention included the following components. (1) Electronic messaging and education were disseminated through a study website (NHCOVIDvaccine.com) and social media venues (eg, Facebook, Instagram). (2) Up to 4 opinion leaders per facility were identified; these were outspoken frontline staff chosen regardless of whether they favored vaccination. Opinion leaders were identified by facility leadership and invited to participate in a 1-hour virtual town-hall meeting led by a racially diverse group of moderators and geriatricians to answer questions, dispel misinformation, and encourage staff to discuss vaccination with their peers. A description of the first 26 of 30 town hall meetings with opinion leaders has been published.18 (3) Gifts (eg, T-shirts, masks) were distributed to staff and residents upon vaccination with socially concerned messaging (“Vaccinated for You!”). (4) Short videos were distributed from community leaders about vaccination. (5) Proxies of unvaccinated patients (for any reason) were referred to a specialist team to facilitate remote informed consent. (6) Funds were allocated for enhanced testing of residents/staff with symptoms after vaccination.

Data Sources and Baseline Characteristics

Resident-level data were obtained from each resident’s electronic medical record (EMR) using the PointClick Care platform including census data, diagnostic codes from admission/status updates, Minimum Data set assessments, and vaccination status. These data were transferred to the data coordinating center at Brown University monthly. Resident characteristics included age, sex, race/ethnicity, influenza vaccination, and comorbidities. History of COVID-19 was considered positive if indicated anywhere in the EMR with the following diagnostic codes: U07.1, J12.82, B94.8, Z86.16.

We additionally collected information on facility characteristics, including bed number, for-profit status, share of residents with Medicaid, having a dementia unit, and 5-star rating from NHCompare.19 Political leaning of the SNF was estimated by the percentage point difference in proportion of Democratic vs Republican votes during the 2020 presidential election in the county in which the SNF was located.20

Outcomes

For residents, the primary outcome was a binary measure indicating whether the resident received 1 or more COVID-19 vaccines through March 2021, ascertained using the facility’s EMR. For staff, the primary outcome was the proportion of staff who received any COVID-19 vaccines through March 2021 obtained from facility logs provided to Insight Therapeutics. For staff, the outcome was aggregated at the facility level: we estimated the proportion of staff vaccinated by dividing the count of eligible staff vaccinated (numerator) by the PBJ estimated number of eligible staff (denominator; see Participants section).

Implementation Fidelity

Implementation was measured via a modified version of the Framework for Implementation Fidelity (FIF),21 assessing content delivered, coverage, frequency, duration, and timeliness of the intervention. Each facility was scored on total adherence, from 0 to 16.

Statistical Analysis

We described baseline characteristics for the study overall and for each treatment arm using means and standard deviations for continuous variables, and proportions for categorical variables. Standardized mean differences were calculated to describe differences between treatment arms. Analyses used an intention-to-treat approach. Mixed-effects, generalized linear models with a binomial distribution that included random site-level effects were used to test the effect of the intervention on resident and staff vaccination rates. In the resident model, we a priori adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, COVID-19 diagnosis, selected comorbidities (eg, dementia), HCS, and the strata of Black resident composition. In a separate model, we included an interaction term for intervention arm and resident race (Black vs other). In the staff model, we adjusted for HCS, strata of Black resident composition, and political leaning of the county, as we had no individual-level data. Using statistical simulation with a range of possible intervention effect sizes and intraclass correlations, we estimated that we would have 80% power to observe a difference of 8% in resident vaccination rates with 60 facilities in the intervention arm.

We conducted 2 post-hoc sensitivity analyses. First, we restricted staff models to nurses and nurse aides excluding other staff (eg, dietary, therapist). Second, because the PPP occurred during the holidays in the midst of COVID-19 outbreaks, we used a longer look-back period to generate an estimate of the number of eligible staff: the average count of unique staff that worked in each facility during the last 2 quarters of 2020.

Results

Facilities and Staff

Of the 133 randomized facilities, 63 were randomized to the intervention arm and 70 to usual care. Facilities were distributed across HCSs as follows: HCS1, n = 18 intervention, n = 20 control; HCS2, n = 15 intervention, n = 16 control; HCS3, n = 18 intervention, n = 19 control; HCS4, n = 12 intervention, n = 15 control. Table 1 shows facility characteristics overall, and stratified by intervention assignment. The mean number of beds was 112 (±55.4), and mean number of staff was 135 (±60). In 33 of the 133 facilities (24.8%), at least 40% of residents were Black. Among staff, 4479 (28%) were nurses and 6472 (40%) nurse aides. Facilities randomized to receive the multicomponent intervention vs usual care had similar 5-star ratings and bed size. A larger proportion of facilities in the intervention arm were located in a county with Republican voters as compared with facilities in the usual care arm.

Table 1. Characteristics of Facilities and Residents in a Trial to Increase COVID-19 Vaccine Coverage Overall, and According to Intervention Arm.

| No. (%) | Standardized mean differencea | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Intervention arm | Usual care arm | ||

| Facility characteristics | ||||

| No. | 133 | 63 | 70 | |

| Bed No., mean (SD) | 112 (55.4) | 114 (56.6) | 110 (54.7) | 0.07 |

| % Black residents | 0.03 | |||

| <25% | 75 (56.4) | 35 (55.6) | 40 (57.1) | |

| 25%-40% | 25 (18.8) | 12 (19.0) | 13 (18.6) | |

| >40% | 33 (24.4) | 16 (25.4) | 17 (24.3) | |

| For-profit | 95 (71.4) | 47 (74.6) | 48 (68.6) | 0.05 |

| Star rating | 0.11 | |||

| 1 | 19 (14.3) | 8 (12.7) | 11 (15.7) | |

| 2 | 32 (24.1) | 16 (25.4) | 16 (22.9) | |

| 3 | 20 (15.0) | 10 (15.9) | 10 (14.3) | |

| 4 | 28 (21.1) | 13 (20.6) | 15 (21.4) | |

| 5 | 33 (24.8) | 16 (25.4) | 17 (24.3) | |

| No. of staff | 122 (55) | 120 (52) | 125 (58) | 0.08 |

| No. of nurses/nursing aids | 83 (44) | 82 (42) | 83 (45) | 0.02 |

| Political leaning of countyb | 0.09 (0.38) | 0.05 (0.38) | 0.12 (0.38) | 0.2 |

| Resident characteristics | ||||

| No. | 7496 | 3631 | 3865 | |

| Age, yc | 0.03 | |||

| <65 | 1547 (20.6) | 789 (20.4) | 758 (20.9) | |

| 65-74 | 1802 (24.0) | 934 (24.2) | 868 (23.9) | |

| 75-84 | 1862 (24.8) | 979 (25.30 | 883 (24.3) | |

| ≥85 | 2241 (29.9) | 1131 (29.3) | 1110 (30.6) | |

| Femalec | 4637 (61.9) | 2354 (60.5) | 2283 (60.9) | 0.04 |

| Race and ethnicityc | 0.03 | |||

| Black | 1973 (26.3) | 1020 (26.4) | 953 (26.2) | |

| Latino | 240 (3.2) | 113 (2.9) | 127 (3.5) | |

| White | 5015 (66.9) | 2588 (67.0) | 2427 (66.8) | |

| COVID-19 diagnosis | 3853 (51.4) | 1906 (49.3) | 1947 (53.6) | 0.09 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Respiratory | 1975 (26.3) | 1057 (27.3) | 918 (25.3) | 0.05 |

| Dementia | 3499 (46.7) | 1715 (44.4) | 1784 (49.1) | 0.09 |

| Coronary artery disease | 1617 (21.6) | 894 (23.1) | 723 (19.9) | 0.08 |

| Congestive heart failure | 165 (21.5) | 859 (22.2) | 756 (20.8) | 0.04 |

| Stroke | 1727 (23.0) | 887 (22.9) | 840 (23.1) | 0.002 |

| Influenza vaccine | 6037 (80.5) | 3071 (79.5) | 2966 (81.7) | 0.05 |

Standardized mean difference (SMD) is calculated as the difference between the mean characteristics in the intervention and usual care arms divided by the standard deviation of the mean characteristics in the total population. SMD ≥ 0.15 indicates imbalance in the distribution of facility and resident characteristics between arms, whereas SMD < 0.15 suggests relative balance between arms.

Political leaning of county: % difference of Democratic vs Republican votes during the 2016 Presidential election by county (scale −1 to 1: 1 indicates 100% of votes for the Republican candidate, 0 an identical number of votes for the Republican and Democratic candidates, and −1 indicates 100% of votes for the Democratic candidate).

Missing <5% of data.

Residents

The trial included 7496 residents: 5905 (79.4%) were aged 65 years or older, and 4637 (61.9%) were female. Nearly 70% (5015; 66.9%) of residents were White, whereas 26.3% were Black and 3.2% Latino (Table 1). More than half (3853; 51.4%) of residents had previously been diagnosed with COVID-19. Residents randomized to the multicomponent intervention vs usual care had similar length of stay and similar burden of respiratory illness. A smaller proportion of residents of SNFs randomized to the intervention were diagnosed with COVID-19 or dementia as compared with residents in facilities in the usual care arm.

Implementation Fidelity

Implementation fidelity varied within and across HCS (median score: 8, range: 3-15; eFigure 1 in Supplement 2). Most intervention facilities (84.1%) sent 1 or more staff (total n = 255) to a town hall meeting, but the extent of engagement varied. All 63 intervention facilities distributed gifts to vaccinated staff and residents; however, only 16 (25.4%) facilities were able to distribute gifts across all 3 clinics. A total of 38% of intervention facilities participated in social media posting/messages. Only 3 facilities used the consenting referral service.

Primary Outcomes

Overall, 81.1% (95% CI, 80.2%-81.9%) of residents were vaccinated. In the intervention arm, 82.5% (95% CI, 81.2%-83.7%) were vaccinated, whereas in the usual care arm, 79.8% (95% CI, 78.5%-81.0%) were vaccinated. eFigure 2 in Supplement 2 shows the percentage of residents vaccinated across HCS. In the adjusted model, there was no difference in the log-odds ratio for resident vaccination by intervention status (0.06; 95% CI, −0.24 to 0.36; Table 2). The average marginal effect of the intervention on resident vaccination was 0.8% (95% CI, −1.9% to 3.7%). There was no evidence of effect modification of Black race on the intervention (logOR −0.09; 95% CI, −0.24 to 0.06).

Table 2. Results of a Multicomponent Intervention on COVID-19 Vaccination Coverage in Skilled Nursing Facility Residents and Staff.

| No. vaccinated | No. eligible | Marginal probability of vaccination (intervention vs usual care), % (95% CI) | Log odds ratio (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention arm | Usual care arm | Intervention arm | Usual care arm | |||

| Primary outcomes in skilled nursing facility residents and staff | ||||||

| Residents | 2994 | 3083 | 3631 | 3865 | 0.8 (−1.9 to 3.7) | 0.06 (−0.24 to 0.36) |

| Staff | 4098 | 4643 | 7555 | 8716 | −1.5 (−3.4 to 0.6) | −0.09 (−0.24 to 0.06) |

| Sensitivity analyses in skilled nursing facility staff | ||||||

| Nurses/nurse aides | 2260 | 2416 | 5159 | 5792 | −0.1 (−2.1 to 2.0) | −0.0.1 (−0.23 to 0.21) |

| Longer look-back to identify eligible staff (July-December 2020) | 4098 | 4643 | 8274 | 9689 | −0.4 (−4.2 to 3.1) | 0.05 (−0.16 to 0.26) |

Overall, 53.7% (95% CI, 53.0%-54.5%) of staff were vaccinated. In the intervention arm, 54.2% (95% CI, 53.1%-54.5%) were vaccinated, whereas in the usual care arm, 53.2% (95% CI, 52.2%-54.3%) were vaccinated. eFigure 3 in Supplement 2 shows the percentage of staff vaccinated across HCS. In the adjusted model, there was no difference in the log-odds ratio for staff vaccination by intervention status (−0.02; 95% CI, −0.25 to 0.20; Table 2). The average marginal effect of the intervention on staff vaccination was −1.5% (95% CI, −3.4% to 0.6%).

Sensitivity Analyses

Results were similar when restricting models to staff who were a nurse or nurse aide (logOR −0.06; 95% CI, −0.23 to 0.35), or when using a longer look-back period (logOR −0.02; 95% CI, −0.25 to 0.20; Table 2).

Discussion

We conducted a pragmatic randomized clinical trial to test the effect of a multicomponent vaccine campaign on COVID-19 vaccination in SNF residents and staff during the initial vaccine roll out with the PPP. Vaccination rates among residents were very high; however, half the staff remained unvaccinated. The multicomponent intervention did not improve vaccination rates in residents or staff with modest implementation of the intervention components. Given the low rates of staff vaccination, there is an urgent need to identify successful vaccination strategies in this setting.

To our knowledge, the present study is the first randomized clinical trial to examine the effect of multiple, common strategies to increase COVID-19 vaccination in SNFs. When designing the intervention, we selected strategies that have been demonstrated to increase influenza vaccination in health care workers. Specifically, the combination of education, frontline champions, and offering gifts (eg, buttons, T-shirts) to vaccinated staff have been successful in increasing influenza vaccination in 2 trials of health care workers.22,23 Our own experience in SNFs reinforces the importance of identifying frontline staff to reinforce educational messages.24,25 Messaging socially concerned motivations (ie, protecting one’s community) has been demonstrated to be an effective strategy to increase influenza vaccination in health care workers.26 Our gifts to vaccinated staff included a goodwill message: “Vaccinated for You!”

We identified many barriers to staff vaccination as described in a prior qualitative report.18 Specifically, frontline staff frequently expressed reservations about the speed of vaccine development and misinformation regarding infertility and pregnancy. Although some concerns appear unique from concerns voiced by health care workers regarding influenza vaccination,27 the overall resident and staff rate of COVID-19 vaccination in our study closely mirrors historic rates of influenza vaccination in SNFs.28,29 A systematic review of trials to increase influenza vaccine uptake in health care workers confirms that multicomponent interventions are more often effective than single interventions. Similarly, a case-control study found facilities that used 9 or more activities (vs ≤5) were 3 times more likely to have high staff COVID-19 vaccination rates than low rates (OR 3.3; 95% CI, 1.2-8.9).30 Our intervention included multiple components; therefore, consideration of additional strategies may be required to achieve high vaccination rates, including the recent Centers for Medicare & Medicaid regulation to require staff vaccination.31,32

While vaccination rates were much higher among SNF residents as compared with staff, resident barriers to vaccination exist. The burden of cognitive impairment is high such that most residents cannot provide informed consent themselves. A survey of 1174 SNFs found that residents were more likely to be vaccinated for influenza if the facility had standard order sets and allowed verbal consent.33 Resident vaccination was high in our study (81.1%), and the addition of a consenting specialist in just 3 facilities did not improve uptake. Instead, facilities should consider standard order sets and procedures for new admissions that ensure the vaccine is broadly offered to all residents.

Much attention has been given to increased vaccine hesitancy among Black and Latino persons. Surprisingly, we found no effect of resident race on the intervention. This is consistent with data from a single state that observed Black residents were less likely to receive influenza vaccination than White residents (absolute difference: 20.5%); however, most of the inequity resulted from Black individuals disproportionately residing in segregated facilities with low-quality care.16 While it is essential to ensure that vaccine campaigns target diverse racial and ethnic populations, assumptions that an intervention may be less effective in certain racial groups may distract from effective outreach to all persons.

Limitations

There are some limitations of the present study. First, most facilities achieved moderate or low implementation fidelity. This was not surprising given the aggressive timeline for vaccination directed by the PPP. Further, the intervention occurred in the midst of the second wave of COVID-19 outbreaks in US SNFs, with most facilities facing sizeable staff shortages and regulatory hurdles (eFigure 4 in Supplement 2). While it is possible that the present study intervention would have been more successful if implemented during a more stable time period, fidelity was consistent with other multicomponent intervention studies in SNFs,34,35,36 suggesting that bundled interventions alone may not improve vaccine uptake. Second, we did not collect information on the quality of implementation. Third, all facilities were engaged in their own strategies to increase vaccination. Most vaccine campaigns were initiated at the corporate level. Because we constrained randomization within HCS, differences in these practices are unlikely to influence our results. Fourth, we did not have individual data on staff, which limits our ability to examine the effect of race or ethnicity on the intervention in staff. Finally, this trial included facilities from 4 HCS with moderate geographic variation. Results may not generalize to all regions.

Although the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services recently announced regulations to mandate staff vaccination in SNFs,32 details of this plan, including whether it will allow test-out options for staff who remain unwilling to be vaccinated, are unavailable. Thus, efforts to increase staff vaccination remain highly relevant, and there are several lessons to be learned from this trial. First, it takes time to demonstrate trustworthiness and build relationships. Facilities should work to identify and train frontline staff ahead of when decisions are finalized regarding booster shots and mandates. Second, many organizations have developed guidelines to encourage vaccination that include the components of our intervention as bundled practices.37,38 The present study results suggest that these efforts may not be enough to change individual behavior. Based on our conversations with facility leadership and frontline staff, we suspect that it is critical to teach champions how to speak with empathy and confidence to other staff about the vaccine. Finally, social processes, including organizational and community culture, are central to successful vaccine campaigns. Minority staff, who have endured structural racism and inequities in the provision of personal protective equipment, may have reason to mistrust leadership. As employer mandates are being implemented, it is critical to create an organizational culture that addresses the concerns of all health care workers and staff. The Institute for Healthcare Improvement has created a framework for examining and improving organizational culture that could be beneficial for SNF leadership who are looking to improve trustworthiness and vaccine coverage.39 Changing organizational culture is likely to have lasting benefits on the quality of care in SNFs beyond the COVID-19 pandemic.

Conclusions

Given the ongoing need to ensure adequate COVID-19 vaccine coverage in SNFs, it is critical to learn from successful and failed vaccine campaigns. The present study results suggest that bundled interventions that use best practices are not enough to increase vaccine rates in SNFs. Future vaccine campaigns must also strive to create an organizational culture that addresses the concerns of all stakeholders, and brings staff and residents/proxies together with the common goal of ending the pandemic.

Trial Protocol

eFigure 1. Variation in IMPACT-C intervention implementation across healthcare systems

eFigure 2. Proportion of SNF residents vaccinated by arm, stratified by percent minority resident status

eFigure 3. Proportion of SNF staff vaccinated by arm, stratified by percent minority resident status

eFigure4. IMPACT-C study timeline

References

- 1.Nearly One-Third of U.S. Coronavirus Deaths are Linked to Nursing Homes. New York Times. June 1, 2021. Accessed December 21, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/us/coronavirus-nursing-homes.html

- 2.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services . COVID-19 Nursing Home Data. Updated December 16, 2021. Accessed December 21, 2021. https://data.cms.gov/covid-19/covid-19-nursing-home-data.

- 3.Foundation HJKF. Total Number of Residents in Certified Nursing Facilities. Accessed December 21, 2021. https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/number-of-nursing-facility-residents/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D

- 4.Shen K, Loomer L, Abrams H, Grabowski DC, Gandhi A. Estimates of COVID-19 cases and deaths among nursing home residents not reported in federal data. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(9):e2122885. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.22885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abbasi J. Social isolation—the other COVID-19 threat in nursing homes. JAMA. 2020;324(7):619-620. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.13484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Artiga S, Rae M, Claxton G, Garfield R. Key Characteristics of Health Care Workers and Implications for COVID-19 Vaccination. January 21, 2021; Accessed December 21, 2021. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/key-characteristics-of-health-care-workers-and-implications-for-covid-19-vaccination/

- 7.Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, et al. ; C4591001 Clinical Trial Group . Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(27):2603-2615. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2034577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baden LR, El Sahly HM, Essink B, et al. ; COVE Study Group . Efficacy and Safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(5):403-416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.White EM, Yang X, Blackman C, Feifer RA, Gravenstein S, Mor V. Incident SARS-CoV-2 infection among mRNA-vaccinated and unvaccinated nursing home residents. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(5):474-476. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2104849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bardenheier BH, Gravenstein S, Blackman C, et al. Adverse events following mRNA SARS-CoV-2 vaccination among U.S. nursing home residents. Vaccine. 2021;39(29):3844-3851. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.05.088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klein NP, Lewis N, Goddard K, et al. Surveillance for adverse events after COVID-19 mRNA vaccination. JAMA. 2021;326(14):1390-1399. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.15072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Disease Control. COVID-19 Vaccine Access in Long-term Care Settings. Accessed December 21, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/long-term-care/pharmacy-partnerships.html.

- 13.Gharpure R, Guo A, Bishnoi CK, et al. Early COVID-19 first-dose vaccination coverage among residents and staff members of skilled nursing facilities participating in the pharmacy partnership for long-term care program—United States, December 2020-January 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(5):178-182. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7005e2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Unroe KT, Evans R, Weaver L, Rusyniak D, Blackburn J. Willingness of long-term care staff to receive a COVID-19 vaccine: a single state survey. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bardenheier BH, Baier RR, Silva JB, et al. Persistence of racial inequities in receipt of influenza vaccination among nursing home residents in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;ciaa1484. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bardenheier B, Wortley P, Ahmed F, Gravenstein S, Hogue CJ. Racial inequities in receipt of influenza vaccination among long-term care residents within and between facilities in Michigan. Med Care. 2011;49(4):371-377. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182054293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Daily Nurse Staffing PBJ. 2021; https://data.cms.gov/Special-Programs-Initiatives-Long-Term-Care-Facili/PBJ-Daily-Nurse-Staffing-CY-2017-Q2/utrm-5phx. Accessed June 18, 2021.

- 18.Berry SD, Johnson KS, Myles L, et al. Lessons learned from frontline skilled nursing facility staff regarding COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69(5):1140-1146. doi: 10.1111/jgs.17136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Medicare.gov. Compare Nursing Home Quality. Accessed December 21, 2021. https://www.medicare.gov/what-medicare-covers/what-part-a-covers/compare-nursing-home-quality.

- 20.Github. United States General Election Presidential Results by County from 2008 to 2016. Accessed December 21, 2021. https://github.com/tonmcg/US_County_Level_Election_Results_08-20

- 21.Carroll C, Patterson M, Wood S, Booth A, Rick J, Balain S. A conceptual framework for implementation fidelity. Implement Sci. 2007;2:40. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-2-40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rothan-Tondeur M, Filali-Zegzouti Y, Golmard JL, et al. Randomised active programs on healthcare workers’ flu vaccination in geriatric health care settings in France: the VESTA study. J Nutr Health Aging. 2011;15(2):126-132. doi: 10.1007/s12603-011-0025-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Riphagen-Dalhuisen J, Burgerhof JG, Frijstein G, et al. Hospital-based cluster randomised controlled trial to assess effects of a multi-faceted programme on influenza vaccine coverage among hospital healthcare workers and nosocomial influenza in the Netherlands, 2009 to 2011. Euro Surveill. 2013;18(26):20512. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES2013.18.26.20512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Loomer L, McCreedy E, Belanger E, et al. Nursing home characteristics associated with implementation of an advance care planning video intervention. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2019;20(7):804-809.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Palmer JA, Parker VA, Mor V, et al. Barriers and facilitators to implementing a pragmatic trial to improve advance care planning in the nursing home setting. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):527. doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-4309-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lytras T, Kopsachilis F, Mouratidou E, Papamichail D, Bonovas S. Interventions to increase seasonal influenza vaccine coverage in healthcare workers: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016;12(3):671-681. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2015.1106656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lorenc T, Marshall D, Wright K, Sutcliffe K, Sowden A. Seasonal influenza vaccination of healthcare workers: systematic review of qualitative evidence. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):732. doi: 10.1186/s12913-017-2703-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gravenstein S, McConeghy KW, Saade E, et al. Adjuvanted influenza vaccine and influenza outbreaks in U.S. nursing homes: Results from a pragmatic cluster-randomized clinical trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;ciaa1916. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McConeghy KW, Davidson HE, Canaday DH, et al. Cluster-randomized trial of adjuvanted vs. non-adjuvanted trivalent influenza vaccine in 823 U.S. nursing homes. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;ciaa1233. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berry SD, Baier RR, Syme M, et al. Strategies associated with COVID-19 vaccine coverage among nursing home staff. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021. doi: 10.1111/jgs.17559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rothstein MA, Parmet WE, Reiss DR. Employer-mandated vaccination for COVID-19. Am J Public Health. 2021;111(6):1061-1064. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.306166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services . Biden-Harris Administration Takes Additional Action to Protect America’s Nursing Home Residents for COVID-19. Accessed September 22, 2021. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/biden-harris-administration-takes-additional-action-protect-americas-nursing-home-residents-covid-19

- 33.Bardenheier B, Shefer A, Ahmed F, Remsburg R, Rowland Hogue CJ, Gravenstein S. Do vaccination strategies implemented by nursing homes narrow the racial gap in receipt of influenza vaccination in the United States? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(4):687-693. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03332.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tappen RM, Wolf DG, Rahemi Z, et al. Barriers and facilitators to implementing a change initiative in long-term care using the INTERACT quality improvement program. Health Care Manag (Frederick). 2017;36(3):219-230. doi: 10.1097/HCM.0000000000000168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Flo E, Husebo BS, Bruusgaard P, et al. A review of the implementation and research strategies of advance care planning in nursing homes. BMC Geriatr. 2016;16:24. doi: 10.1186/s12877-016-0179-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lund S, Richardson A, May C. Barriers to advance care planning at the end of life: an explanatory systematic review of implementation studies. PLoS One. 2015;10(2):e0116629. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Agency for Healthcare Research and. Quality . Invest in trust: a guide for building COVID-19 vaccine trust and increasing vaccination rates among CNAs. Accessed December 21, 2021. https://www.ahrq.gov/nursing-home/materials/prevention/vaccine-trust.html

- 38.Coalition NPHI. COVID-189 Vaccine Education Toolkit. 2021; https://www.nphic.org/cvirus-adcouncil-toolkit. Accessed June 21, 2021.

- 39.Perlo J, Balik B, Swensen S, Kabcenell A, Landsmen J, Felley D. IHI Framework for Improving Joy at Work. IHI White Paper: Institute for Healthcare Improvment; 2017.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

eFigure 1. Variation in IMPACT-C intervention implementation across healthcare systems

eFigure 2. Proportion of SNF residents vaccinated by arm, stratified by percent minority resident status

eFigure 3. Proportion of SNF staff vaccinated by arm, stratified by percent minority resident status

eFigure4. IMPACT-C study timeline