Abstract

Objective:

To assess the scientific evidence that rapid maxillary expansion (RME) causes Adverse Effects on the midpalatal suture, vertical dimension, dental and periodontal structures in growing subjects.

Materials and Methods

Electronic databases were searched for articles dated through December 2011. The quality of the studies was ranked on a 13-point scale in which 1 was the low end of the scale and 13 was the high end.

Results:

Thirty relevant articles were identified. The amount of midpalatal suture opening ranged from 1.6 to 4.3 mm in the anterior region and from 1.2 to 4.4 mm in the posterior region. At the end of the active phase, RME resulted in slight inferior movement of the maxilla (SN-PNS +0.9 mm; SN-ANS +1.6 mm), increased tipping of anchored teeth from 3.4° to 9.2° and bending of the alveolar bone from 5.1° to 11.3°. In the long term, RME did not modify the facial growth patterns, and no significant changes on dentoalveolar structures were observed. Of the 30 studies, 2 were medium-high quality, 8 were medium quality, and 20 were low quality.

Conclusions:

RME always opened the midpalatal suture in growing subjects. The vertical changes were small and transitory. In the long-term evaluation, an uprighting of anchored teeth was observed and periodontal structures were not compromised.

Keywords: Rapid maxillary expansion, Orthopedic treatment, Growing subjects

INTRODUCTION

Rapid maxillary expansion (RME) is a common orthopedic procedure indicated for the treatment of maxillary transverse deficiency. The orthopedic expansion occurs in growing subjects with immature skeletal development when the force applied to the teeth and the maxilla exceeds the limits needed for tooth movement.1 The applied force causes widening and gradual opening of the midpalatal suture, compression of the periodontal ligament, bending of the alveolar processes, and dental tipping.2,3

Although RME has been recognized as a safe and reliable orthopedic procedure that allows correction of the maxillary transverse deficiency in growing patients, some investigations4–10 have focused on the unwanted consequences of heavy forces on sutures, periodontal alveolar bone, and dental structures identified as “Adverse Effects” (AEs). Moreover, other authors11,12 have reported that RME with conventional appliances promotes the anterior and inferior displacement of the maxilla with a consequent posterior-inferior rotation of the mandible.

The present systematic review was undertaken to answer the following questions on RME in growing subjects: Is RME always effective in opening the midpalatal suture? Does RME increase the vertical skeletal dimension? Does RME produce detrimental effects on dental and periodontal structures?

MATERIALS AND METHODS

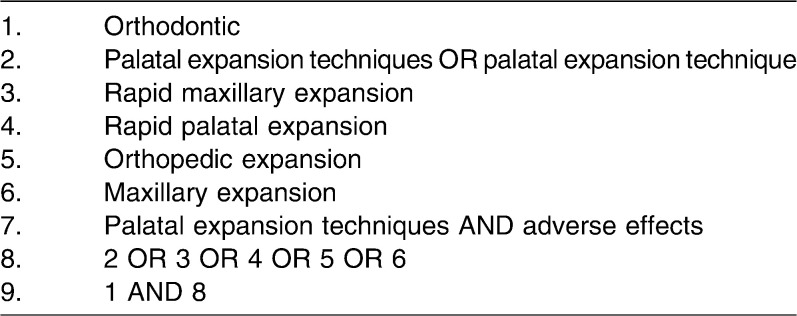

The PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Clinical Trials, Web of Knowledge, Ovid, and Scopus databases were searched, and hand research using other sources, such as orthodontic books, was conducted for studies dated through December 2011 in order to identify articles reporting possible AEs of RME on dentoalveolar and skeletal structures in growing subjects. The search strategy used in this review is shown in Table 1.

Table 1. .

Search Strategy

Based on data from the titles and abstracts of the retrieved studies, two investigators selected articles that met the following inclusion criteria:

Studies on human growing subjects (maximum chronological age of 17 years), published in English, Italian, French, or German;

Studies on orthopedic maxillary expansion;

Studies that included clear descriptions of the materials and technique applied;

Prospective and retrospective original studies with a minimum of 10 subjects in the study sample.

The exclusion criteria were studies with orthodontic and surgical techniques, case reports, reviews, abstracts, author debates, summary articles, and studies on animals or adults. The reference lists of these articles were perused, and references related to the articles were followed up. If there was disagreement between the investigators, inclusion of the study was confirmed by mutual agreement.

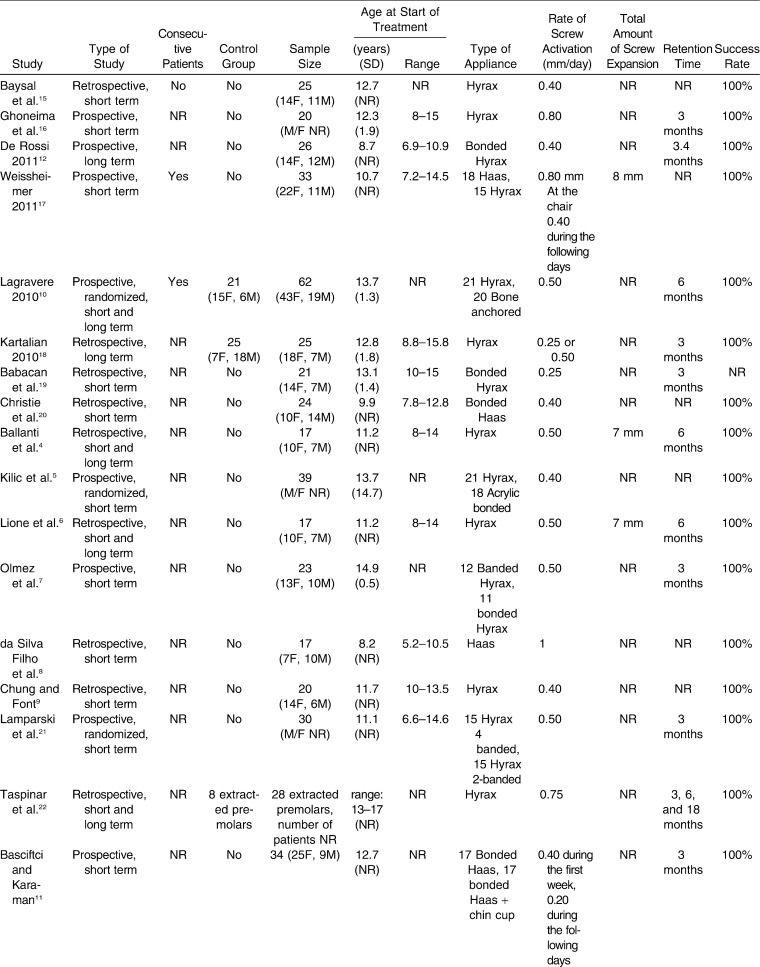

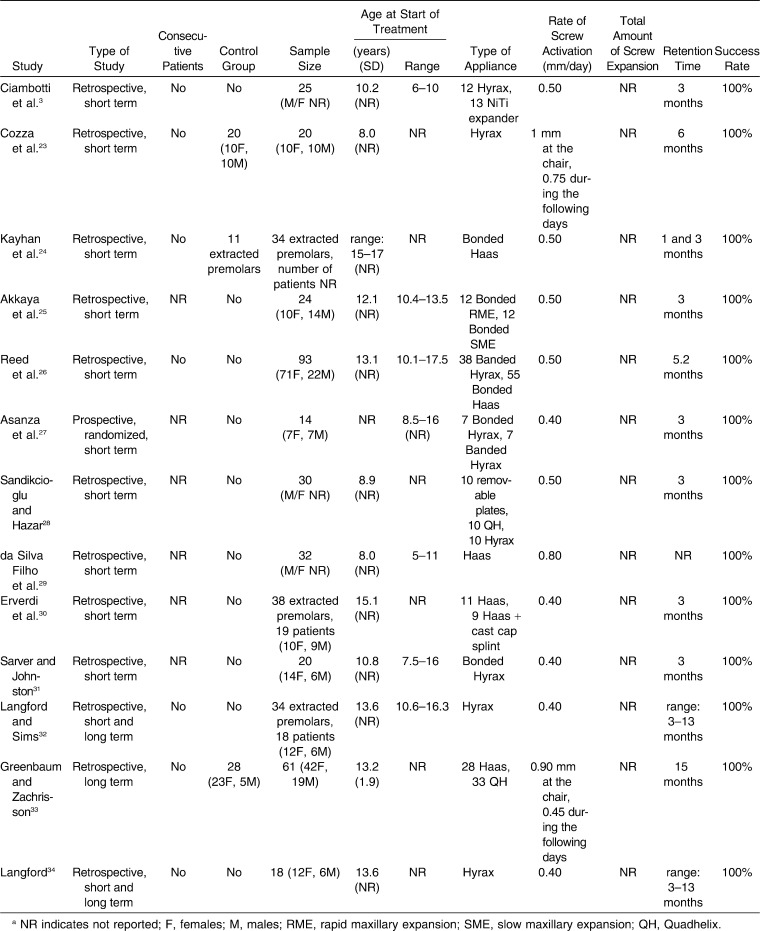

From the identified articles, the investigators independently extracted data referring to the year of publication, type of study, sample size, chronological age of subjects at the start of treatment, type of appliance, rate of activation, amount of expansion, duration of retention, and success rate (Table 2).

Table 2. .

Characteristics of the Samples, Expansion Techniques, and Outcomes in the Included Studiesa

Table 2. .

Continued

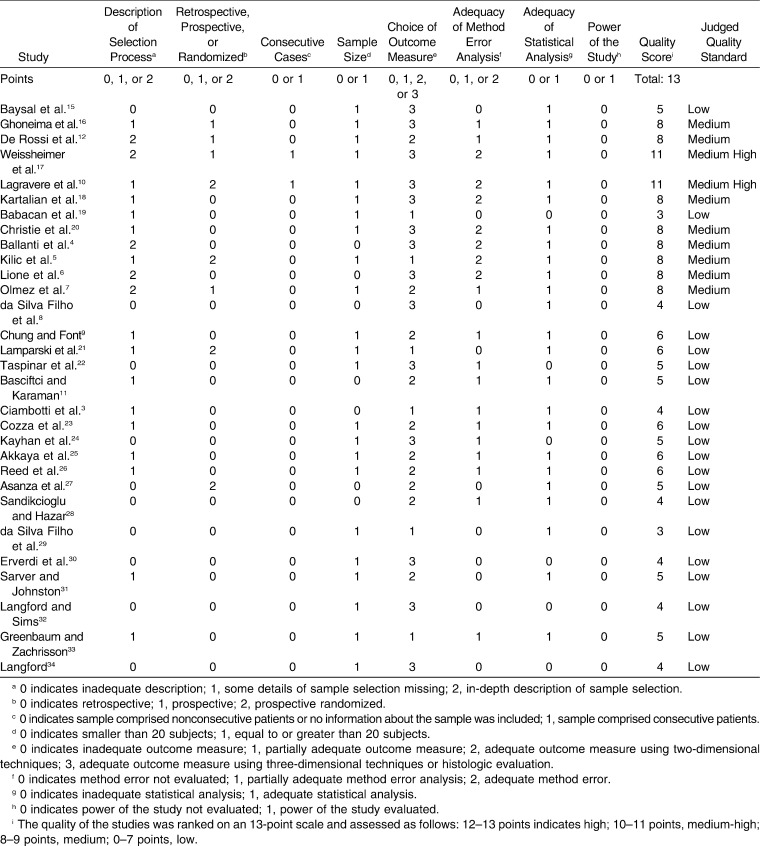

According to the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination and to the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) statement, evaluation of methodological quality gives an indication of the strength of evidence provided by the study because flaws in the design or conduct of a study can result in bias. However, no single approach for assessing methodological soundness is appropriate to all systematic reviews.13,14 Quality assessment, performed independently by the investigators, comprised evaluation of the sample selection process, sample size estimation, adequacy of outcome measures, adequacy of method error estimation, and adequacy of statistical analysis. If there was disagreement between the investigators, consensus was reached after discussion. The quality of the studies was ranked on a 13-point scale and assessed as follows: high quality, a total score of 12 or 13 points; medium-high quality, a total score of 10 or 11 points; medium quality, a total score of 8 or 9 points; and low quality, a total score equal to or below 7 points.

Statistical Analysis

A meta-analysis of the results of the studies that used comparable techniques of maxillary expansion was planned. Heterogeneity of the studies was assessed first by calculating the I2 index. According to the recommendation of the Cochrane Collaboration, if heterogeneity is high (I2 > 75%), a meta-analysis might produce misleading results, and omitting it from a systematic review should be considered.13,14

RESULTS

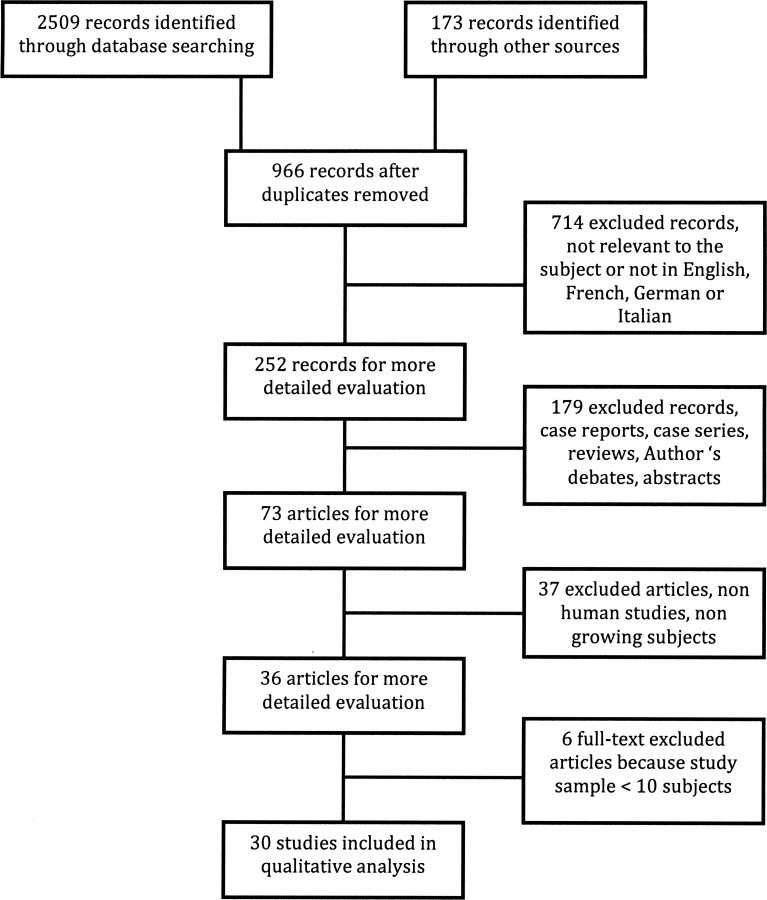

A search using the U.S. National Library of Medicine's MeSH (medical subject headings) terms yielded the following results: PubMed yielded 146 publications; Embase, 546 publications; Cochrane Central, 92 publications; ISI Web Knowledge, 617 publications; and Ovid, 423 publications; Scopus, 685 publications. In addition, 173 records were identified through hand research. There was overlap among the databases. Application of the inclusion and exclusion criteria and follow-up on the referred studies identified 30 relevant publications (Figure 1).3–4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,15–16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34

Figure 1. .

PRISMA flow diagram. Flow chart illustrating the selection of relevant articles.

Heterogeneity of the results of the investigations with similar technique of maxillary expansion was high (>85%). A meta-analysis was not performed for this reason. Twenty-one studies3,4,6,8,9,15,18–19,20,22–23,24,25,26,28–29,30,31,32,33,34 were retrospective, five studies7,11,12,16,17 were prospective, and four studies5,10,21,27 were prospective and randomized. Six studies10,18,22–23,24,33 compared the results with a control group of the same age, and eight studies4,6,10,12,22,32–33,34 analyzed the long-term effects of RME. Only two studies10,17 specified that the subjects of the study groups were selected consecutively. Mean age at the start of orthopedic expansion in the evaluated samples ranged from 7 to 17 years. Overall, in 24 studies3,4–5,6,7,9–10,11,15–16,17,18,19,21,22,24–25,26,27,30–31,32,33,34 the sample comprised teenagers; in six studies,8,12,20,23,28,29 the sample was younger than 10 years (mean age, 8.6 years). The devices applied were bonded with acrylic coverage on the occlusal surface of posterior upper teeth or banded with the 2 or 4 anchored tooth (Hyrax or Haas type maxillary expanders). The methods used to detect the treatment effects were different: two studies3,5 used the dental casts before and after treatment, 11 studies9,11,12,21,23,25–26,27,28,29,31 used bidimensional radiographic techniques, 10 studies4,6–7,8,10,15–18,20 used tridimensional radiographic techniques, 5 studies22,24,30,32,34 used histological evaluation, and 2 studies19,33 used other methods, such as probe and intraoral measure of pulpal blood flow.

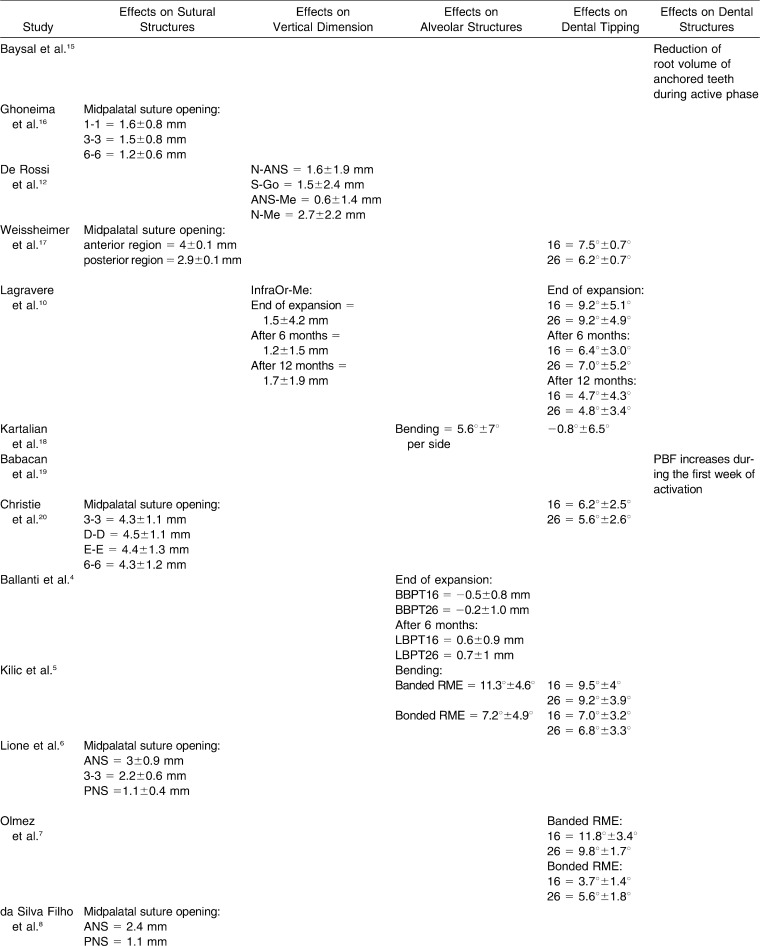

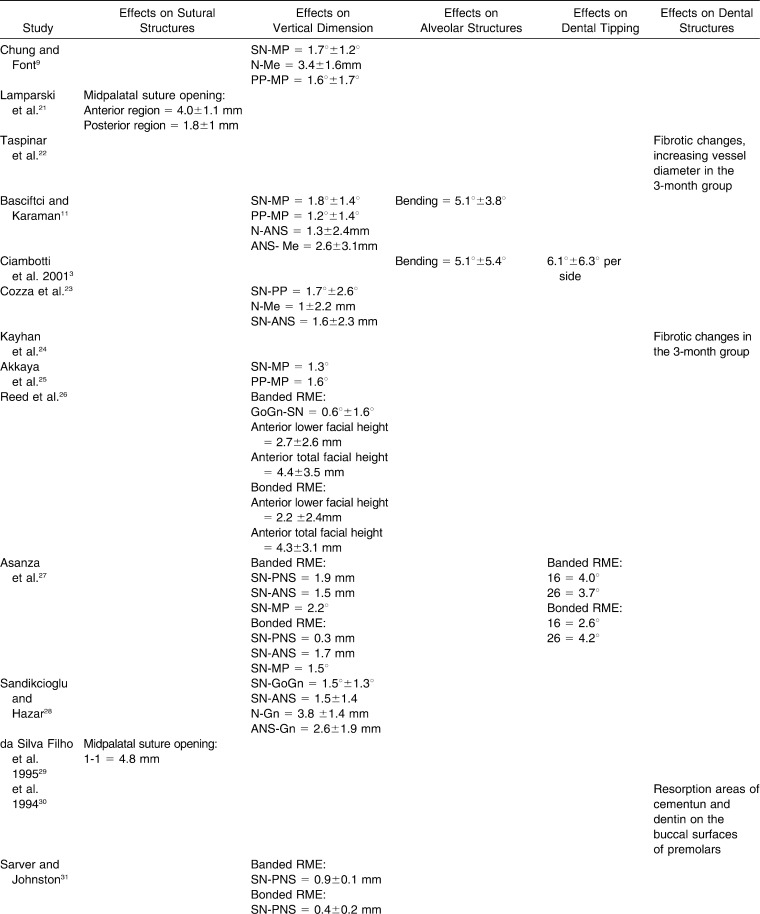

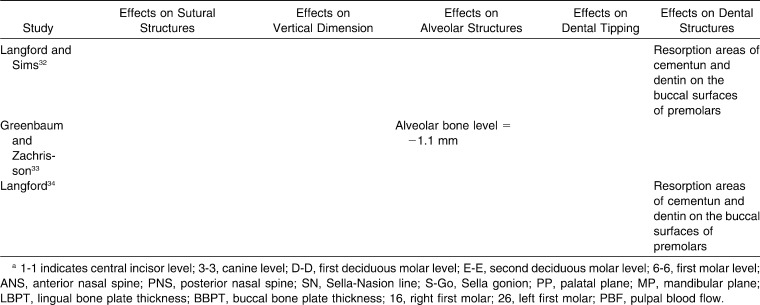

RME was used to treat transverse maxillary deficiency, and the device was maintained in situ as a passive retainer for a minimum of 3 months and a maximum of 18 months. The screw was activated twice a day in 25 studies,3–4,5,6,7,9–10,11,12,15,17,18,20,21,24–25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34 once a day in 1 study,19 and more than twice a day in 4 studies.8,16,22,23 All the included studies used a clinical evaluation, such as molar contact or overcorrection of 2–3 mm, to assess the required expansion. Only three investigations4,6,17 reported that the required expansion corresponded to a precise amount of screw expansion of 7 mm4,6 and 8 mm.17 The effects of RME are shown in Table 3.

Table 3. .

Effects Evaluated in the Included Studiesa

Table 3. .

Continued

Table 3. .

Continued

Quality Analysis

Research quality or methodological soundness was medium-high in 2 studies10,17 (6.7%), medium in 8 studies4–5,6,7,12,16,18,20 (26.7%), and low in 20 studies3,8,9,11,15,19,21–22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34 (66.7%). Twenty-one studies3,4,6,8,9,15,18–20,22–23,24,25,26,28–29,30,31,32,33,34 were retrospective, five studies were prospective,7,10,11,16,17 and only four studies5,10,21,27 were prospective and randomized. Withdrawals (dropouts) were declared in only one study.19 The most recurrent shortcomings were small sample size with no consecutive cases, except for two studies,10,17 implying low power, problems of bias and confounding variables, lack of method error analysis, blinding in measurements, and deficiency or lack of statistical methods. Furthermore, no study declared any power analysis and only seven studies4–5,6,10,17,18,20 discussed the possibility of a type II error occurring. Finally, six studies20,22,24,30,32,34 did not perform a statistical analysis, focusing instead on a qualitative description of the results (Table 4).

Table 4. .

Description of Quality Score Assignment

DISCUSSION

The aim of the present systematic review was to assess whether RME causes AEs on dentoskeletal structures in growing subjects. With respect to previous reviews35,36 on RME, all studies that used computed tomography, which provides a more accurate three-dimensional assessment of changes induced by orthopedic forces, were searched and perused.

This systematic review included both retrospective and prospective studies, of which only four5,10,21,27 were randomized. The methodology of these investigations was generally of low and medium quality (Table 4); therefore, the findings should be interpreted with caution. A very serious limitation of most studies was the lack of an adequate untreated control group.

The analysis of the 30 articles3–4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,15–16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34 included in the present review suggests that RME is an effective procedure that always produces transverse skeletal effects on the maxilla by opening the midpalatal suture in growing subjects, regardless of the type of palatal expander. Results showed that RME treatment was able to induce significantly more favorable skeletal changes in the transverse plane when it was initiated before the pubertal peak in skeletal growth.6,8,16,17,20,29,37 Indeed, the studies that reported a wider opening of midpalatal suture were those20,29 in which the study sample was younger, thereby confirming the role of treatment timing in the determination of skeletal modifications following RME therapy. In all studies the amounts of midpalatal suture opening were greater in the anterior region than the posterior region, except in the study by Christie et al.,20 who found a parallel manner of midpalatal suture opening.

RME treatment has been associated with downward movement of the maxillary posterior teeth and the maxilla.1–2,3,9,11 As reported by several articles included in the present review,9–10,11,12,23,25–26,27,28,31 RME resulted in slight inferior movement of the maxilla, as demonstrated by changes in the measurements SN-PNS (+0.9 mm) and SN-ANS (+1.6 mm). Several authors9–10,11,12,23,25–26,27,28,31 pointed out that this downward movement of the maxilla and premature dental contacts are responsible for the mandible rotation in a downward and backward direction with a mean increase in the following variables: SN-MP, 1.7°; PP-MP, 1.5°; SN-PP, 1.6°; SN-GoGn, 1.1°.9–10,11,12,23,25–26,27,28,31 Changes in vertical dimension before and after treatment with RME were less than 2 mm or 2°, and they may be not considered clinically relevant.38 In the short-term evaluation the only variable with a greater increase was the total anterior facial height (N-Me: 3.2 mm), which could be the transitory result of occlusal interferences.9,12,23,26

Though the maxilla was displaced downward, the facial growth patterns and/or the direction of mandibular growth were not modified 6 months after RME appliance removal, as observed in the only two long-term studies, those of De Rossi et al.12 and Lagravere et al.10 These findings corroborate the results of other studies39,40 that also evaluated longitudinally the vertical effects associated with the RME, although in those cases RME was followed by other orthodontic therapy.39,40 Moreover, Lagravere et al.10 and Cozza et al.23 reported that, compared with an untreated control group, changes in vertical dimension were negligible.10,23 The bonded RME showed less inferior movement of PNS with respect to the banded RME.26,27,31 This might be due to the interocclusal acrylic acting as an intrusive force to the basal bone of the maxilla by violating the freeway space and causing a passive stretch of the elevator musculature. The outcomes of the retrieved studies indicated an element of vertical control using a bonded RME to counteract the AEs seen with other expansion devices.26,27,31

Seven articles3,5,7,10,17,20,27 showed that heavy forces produced an increased buccal inclination of anchored teeth at the end of active phase regardless of the type of expanders.3,5,7,10,17,20,27 Ciambotti et al.3 and Kilic et al.5 observed in the short term not only the dental tipping but also the effects of RME on alveolar structures; they found that the alveolar halves splayed buccally and carried the teeth with them. In growing subjects, anchored teeth and the alveolar bone are moved at the same time with the same magnitude and direction.3,5 The inclination of the posterior teeth in the bonded RME group appeared to be more stable for the action of the acrylic coverage.5,7 Lagravere et al.10 reported that 12 months after the end of active expansion the dental tipping appeared reduced by about half because of expansion relapse.10 Kartalian et al.18 compared measurements made on cone-beam CT scans between patients with RME treatment and controls after a mean interval of 17.9 months. The RME group showed that the alveolus tipped buccally by 5.6° but the angulation of the dentition remained constant (−0.8°) before and after treatment, probably because of postexpansion relapse of dental axial angulation.18

Greenbaum and Zachrisson33 demonstrated that, after a retention period of 3 months, expansion groups exhibited minimal differences in periodontal condition compared with the control group.33 Ballanti et al.,4 by using computed tomography axial scans, reported that orthopedic forces in prepubertal subjects did not affect the alveolar bone palatal and buccal thickness after a 6-month retention period. A 6-month period was necessary to allow recovery of the alveolar plate when the movement of anchored teeth is completed.4

Five articles evaluated histopathologically the vascular changes and root resorption of anchor extracted premolars after RME therapy.22,24,30,32,34 Kayhan et al.24 and Taspinar et al.22 observed the greatest fibrotic changes in periodontal bone in the 3-month group, less in the 6-month group, and very slight in the 18-month group. These fibrotic changes may represent the result of increasing duration of excessive force application, or they may occur as a result of the start of tooth movement.22,24 Taspinar et al.22 found significantly increased vessel diameter inside the pulp, which disappeared 18 months after RME. Babacan et al.19 observed increased pulpal blood flow (PBF) during the first week of activation and PBF similar to initial values during the retention period, indicating that the vascular changes are reversible.19 Langford,34 Langford and Sims,32 and Erverdi et al.30 demonstrated that continuous heavy forces as well as relapse forces capable of causing significant root resorption operate for up to 3 months after RME.Active resorption slowed significantly after about 3 months, with an evident trend to increased filling with cellular cementum of resorptive defects.30,32,34 Finally, Baysal et al.15 performed cone beam computed tomography to assess the root volume and reported that in a study group with a mean age of 12.7 years all investigated roots showed statistically significant volume loss after RME, with no difference between anchored and non-anchored teeth.15 The highest mean volume loss, 18.6 mm3, was recorded for the mesiobuccal root of the first molars, while Zachrisson41 reported that 2-mm apical root shortening was not detrimental to the function of dentition.15,41

CONCLUSIONS

Most of the studies presented with methodological problems: small sample size, bias and confounding variables, lack of method error analysis, blinding in measurements, and deficient or missing statistical methods. The quality level of the studies was not sufficient enough to draw any evidence-based conclusions.

RME is an effective procedure that is able to produce always transverse skeletal effects on the maxilla by opening the midpalatal suture in growing subjects regardless of the type of palatal expander.

The vertical changes found after RME treatment, although statistically significant, were small and probably transitory. The bonded maxillary expansion appliance could be a viable option for correcting a narrow maxilla, regardless of the patient's vertical problems or facial pattern.

In growing subjects, heavy forces in the short-term evaluation moved anchored teeth and the alveolar bone at the same time and with the same magnitude and direction. In the long-term evaluation, an uprighting of anchored teeth was observed. Vascular changes after RME are reversible, and active root resorption appeared along with increased filling with cellular cementum after 3 months.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wertz RA. Skeletal and dental changes accompanying rapid midpalatal suture opening. Am J Orthod. 1970;58:41–64. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(70)90127-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haas AJ. Palatal expansion: just the beginning of dentofacial orthopedics. Am J Orthod. 1970;57:219–255. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(70)90241-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ciambotti C, Ngan P, Orth C, Durkee M, Kohli K, Kim H. A comparison of dental and dentoalveolar changes between rapid palatal expansion and nickel-titanium palatal expansion appliances. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2001;119:11–20. doi: 10.1067/mod.2001.110167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ballanti F, Lione R, Fanucci E, Franchi L, Baccetti T, Cozza P. Immediate and post-retention effects of rapid maxillary expansion investigated by computed tomography in growing patients. Angle Orthod. 2009;79:24–29. doi: 10.2319/012008-35.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kilic N, Kiki A, Oktay H. A comparison of dentoalveolar inclination treated by two palatal expanders. Eur J Orthod. 2008;30:67–72. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjm099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lione R, Ballanti F, Franchi L, Baccetti T, Cozza P. Treatment and posttreatment skeletal effects of rapid maxillary expansion studied with low-dose computed tomography in growing subjects. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2008;134:389–392. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2008.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olmez H, Akin E, Karacay S. Multitomographic evaluation of the dental effects of two different rapid palatal expansion appliances. Eur J Orthod. 2007;29:379–385. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjm034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Da Silva Filho OG, Lara TS, da Silva HC, Bertoz AF. Post expansion evaluation of the midpalatal suture in children submitted to rapid palatal expansion: a CT study. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2006;31:142–148. doi: 10.17796/jcpd.31.2.tu54hu4231w1073q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chung C-H, Font B. Skeletal and dental changes in the sagittal, vertical, and transverse dimensions after rapid palatal expansion. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2004;126:569–575. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2003.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lagravere MO, Carey J, Heo G, Toogood RW, Major PW. Transverse, vertical, and anteroposterior changes from bone-anchored maxillary expansion vs traditional rapid maxillary expansion: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2010;137:304.e1–304.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2009.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Basciftci FA, Karaman AI. Effects of a modified acrylic bonded rapid maxillary expansion appliance and vertical chin cap on dentofacial structures. Angle Orthod. 2002;72:61–71. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(2002)072<0061:EOAMAB>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Rossi M, De Rossi A, Abrao J. Skeletal alterations associated with the use of bonded rapid maxillary expansion appliance. Braz Dent J. 2011;22:334–339. doi: 10.1590/s0103-64402011000400013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. The PRISMA group (2009) Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Chichester, UK : Wiley-Blackwell; 2008. The Cochrane Collaboration; pp. 276–282. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baysal A, Karadede I, Hekimoglu S, Ucar F, Ozer T, Veli I, Uysal T. Evaluation of root resorption following rapid maxillary expansion using cone-beam computed tomography. Angle Orthod. 2011 August 15 doi: 10.2319/060411-367.1. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghoneima A, Abdel-Fattah E, Hartsfield J, El-Bedwehi A, Kamel A, Kula K. Effects of rapid maxillary expansion on the cranial and circummaxillary sutures. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2011;140:510–519. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2010.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weissheimer A, de Menezes LM, Mezomo M, Dias DM, Santayana de Lima EM, Deon Rizzatto SM. Immediate effects of rapid maxillary expansion with Haas-type and hyrax-type expanders: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2011;140:366–376. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2010.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kartalian A, Gohl E, Adamian M, Enciso R. Cone-beam computerized tomography evaluation of the maxillary dentoskeletal complex after rapid palatal expansion. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2010;138:486–492. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2008.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Babacan H, Doruk C, Bicakci AA. Pulpal blood flow changes due to rapid maxillary expansion. Angle Orthod. 2010;80:1136–1140. doi: 10.2319/031010-139.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Christie KF, Boucher N, Chung C-H. Effects of bonded rapid palatal expansion on the transverse dimensions of the maxilla: a cone-beam computed tomography study. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2010;137:S79–S85. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2008.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lamparski DG, Rinchuse DJ, Close JM, Sciote JJ. Comparison of skeletal and dental changes between 2-point and 4-point rapid palatal expanders. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2003;123:321–328. doi: 10.1067/mod.2003.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taspinar F, Akgul N, Simsek G, Ozdabak N, Gundogdu C. The histopathologic investigation of pulpal tissue following heavy orthopaedic forces produced by rapid maxillary expansion. J Int Med Res. 2003;31:197–201. doi: 10.1177/147323000303100305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cozza P, Giancotti A, Petrosino A. Rapid palatal expansion in mixed dentition using a modified expander: a cephalometric investigation. J Orthod. 2001;28:129–134. doi: 10.1093/ortho/28.2.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kayhan F, Kucukkeles N, Demirel D. A histologic and histomorphometric of pulpal reactions following rapid palatal expansion. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2000;117:465–473. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(00)70167-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Akkaya S, Lorenzon S, Ucem TT. A comparison of sagittal and vertical effects between bonded rapid and slow maxillary expansion procedures. Eur J Orthod. 1999;21:175–180. doi: 10.1093/ejo/21.2.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reed N, Ghosh J, Nanda RS. Comparison of treatment outcomes with banded and bonded RPE appliances. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1999;116:31–40. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(99)70300-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Asanza S, Cisneros GJ, Nieberg LG. Comparison of Hyrax and bonded expansion appliances. Angle Orthod. 1997;67:15–22. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1997)067<0015:COHABE>2.3.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sandikcioglu M, Hazar S. Skeletal and dental changes after maxillary expansion in the mixed dentition. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1997;111:321–327. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(97)70191-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.da Silva Filho OG, do Prado Montes LA, Torelly LF. Rapid maxillary expansion in the deciduous and mixed dentition evaluated through posteroanterior cephalometric analysis. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1995;107:268–275. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(95)70142-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Erverdi N, Okar I, Kucukkeles N, Arbak S. A comparison of two different rapid palatal expansion techniques from the point of root resorption. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1994;106:47–51. doi: 10.1016/S0889-5406(94)70020-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sarver DM, Johnston MW. Skeletal changes in vertical and anterior displacement of the maxilla with bonded rapid palatal expansion appliances. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1989;95:462–466. doi: 10.1016/0889-5406(89)90409-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Langford SR, Sims MR. Root surface resorption, repair, and periodontal attachment following rapid maxillary expansion in man. Am J Orthod. 1982;81:108–115. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(82)90034-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Greenbaum KR, Zachrisson BU. The effect of palatal expansion therapy on the periodontal supporting tissues. Am J Orthod. 1982;81:12–21. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(82)90283-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Langford SR. Root resorption extremes resulting from clinical RME. Am J Orthod. 1982;81:371–377. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(82)90074-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lagravere MO, Major PW, Flores-Mir C. Long-term skeletal changes with rapid maxillary expansion: a systematic review. Angle Orthod. 2005;75:1046–1052. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(2005)75[1046:LSCWRM]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lagravere MO, Major PW, Flores-Mir C. Long-term dental arch changes after rapid maxillary expansion treatment: a systematic review. Angle Orthod. 2005;75:155–161. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(2005)075<0151:LDACAR>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baccetti T, Franchi L, Cameron CG, McNamara JA., Jr Treatment timing for rapid maxillary expansion. Angle Orthod. 2001;71:343–350. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(2001)071<0343:TTFRME>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cozza P, Baccetti T, Franchi L, DeToffol L, McNamara Mandibular changes produced by functional appliances in Class II malocclusion: a systematic review. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2006;129:599.e1–599.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2005.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chang JY, McNamara JA, Herberger TA. A longitudinal study of skeletal side effects induced by rapid maxillary expansion. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1997;112:330–333. doi: 10.1016/S0889-5406(97)70264-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Velazquez P, Benito E, Braco La. Rapid maxillary expansion. A study of the long term effects. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1996;109:361–367. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(96)70117-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zachrisson BU. Iatrogenic tissue damage following orthodontic treatment. Trans Eur Orthod Soc. 1975:488–501. [Google Scholar]