ABSTRACT

A 36-year-old woman presented to hospital 9 days after receiving her first dose of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine with fever, myalgia and a sore throat. She was previously fit and well with no prior vaccine reactions.

There was no clinical response to initial treatment with intravenous (IV) antibiotics. Microbiology tests including for COVID-19 were negative. At day 5, she developed pleuritic pain and a pericardial rub. Echocardiography and subsequent cardiac magnetic resonance imaging showed evidence of constrictive pericarditis. Computed tomography revealed gross hepatomegaly and moderate splenomegaly. Blood tests showed raised inflammatory markers, deranged clotting, low platelets and a marked hyperferritinaemia.

A presumptive diagnosis of a multi-system inflammatory disorder secondary to recent COVID-19 vaccination was made and high-dose IV methylprednisolone initiated. Following a high ‘H score’ of 70%–80% a diagnosis of secondary haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) was made. She was treated with IV immunoglobulin with subsequent clinical response.

HLH is a rare syndrome of acute and rapidly progressive systemic inflammation characterised by cytopenias, excessive cytokine production and hyperferritinaemia. The adult form has multiple triggers, including recent vaccination. This case prompts awareness among clinicians of HLH as a rare complication of COVID-19 vaccination but should not discourage individuals from vaccination.

KEYWORDS: HLH, covid, vaccination, inflammation, hyperferritinaemia

Case presentation

A 36-year-old woman, a carer with no previous medical history, presented to hospital with fever, myalgia and sore throat. She had received a first dose of the ChAdOx1 COVID-19 vaccination (Oxford–AstraZeneca) 9 days previously. Three days post-vaccine, she experienced mild facial swelling that resolved with oral antihistamines. At day 5, she developed fever (>42°C) and severe myalgia. Her symptoms progressed despite simple analgesia and she was admitted to hospital. Medication, family, travel and sexual histories were unremarkable. She reported no previous adverse reactions to vaccines, or allergies to food or drugs. Admission observations were a temperature of 39.9°C, respiratory rate of 32 breaths per minute, heart rate of 137 beats per minute, blood pressure of 104/65 mmHg and oxygen saturations of 97% on air. Clinical examination was unremarkable except mild right upper quadrant abdominal tenderness with hepatomegaly. There was no rash, joint-swelling or synovitis.

Admission electrocardiography showed sinus tachycardia. Chest X-ray was unremarkable. Urine dip was positive for protein, ketones and haemoglobin. Inflammatory markers were raised with normal renal, liver and coagulation screens (Table 1). Serial viral polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests for SARS-CoV-2 infection and routine microbiology tests (blood and urine cultures, respiratory viral PCR screen, urinary antigens for Legionella and pneumococcus) were all negative. Serological testing for cytomegalovirus (CMV), Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), HIV, and hepatitis B and C showed no evidence of active or prior infection. She was treated for suspected sepsis secondary to infection of uncertain aetiology with IV piperacillin/tazobactam, analgesia and fluids.

Table 1.

Investigations summary

| Day 1 | Day 7 | |

| Biochemistry | ||

| Urea and electrolytes | Normal | Normal |

| C-reactive protein, mg/L | 207 | 339 |

| Alanine transaminase, U/L | 38 | 15 |

| Alkaline phosphatase, U/L | 76 | 245 |

| Albumin, g/L | 36 | 17 |

| Albumin adjusted calcium, mmol/L | 2.19 | 2.07 |

| Creatine kinase, U/L | 42 | 390 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase, U/L | - | 351 |

| Procalcitonin, ng/mL | - | 38.7 |

| Ferritin, μg/L | - | 12,423 |

| Triglycerides, mmol/L | - | 1.8 |

| Haematology | ||

| Haemoglobin, g/L | 140 | 115 |

| White cell count, × 109/L | 12.8 | 28.7 |

| Platelets, × 109/L | 210 | 243 |

| Prothrombin time, seconds | 12 | 16 |

| Activated partial thromboplastin time, seconds | 25 | 31 |

| Fibrinogen, g/L | - | 5.5 |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate, mm/hour | - | 7 |

| Immunology | ||

| Immunoglobulins | Normal | |

| Antinuclear antibody, extractable nuclear antigen antibody, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody and liver autoantibody screen | Negative | |

| Microbiology | ||

| Blood cultures (nine sets) | All negative | |

| Urine cultures | Negative | |

| Respiratory viral screen (influenza A & B, respiratory syncytial virus, parainfluenza, enterovirus, rhinovirus, metapneumovirus, adenovirus and seasonal coronavirus) | Negative | |

| Urinary antigens (Legionella and Streptococcus pneumoniae) | Negative | |

| Mycoplasma pneumoniae | Negative | |

| HIV serology | Negative | |

| Epstein–Barr virus serology | Negative | |

| Cytomegalovirus serology | Negative | |

After 5 days in hospital, she remained pyrexial, tachycardic and tachypnoeic and developed pleuritic pain and a pericardial rub. Repeat bloods showed increasing C-reactive protein of 339 mg/L, white cell count of 33.5 × 109/L, neutrophils of 31.2 × 109/L, marked hyperferritinaemia of 12,423 μg/L and deranged clotting with raised fibrinogen (prothrombin time of 16 seconds, activated partial thromboplastin time of 31 seconds and fibrinogen of 5.5 g/L) but normal haemoglobin, platelets and erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Computed tomography of the thorax, abdomen and pelvis revealed gross hepatomegaly, moderate splenomegaly and small bilateral pleural effusions, but no lymphadenopathy. Electrocardiography demonstrated ST elevation in leads V1–2 and serial troponins were 162 ng/L and 154 ng/L. Findings on bedside echocardiography and subsequent cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) were consistent with constrictive pericarditis. Thoracic ultrasound showed simple bilateral anechoic pleural effusions. MRI of brain and spine were normal.

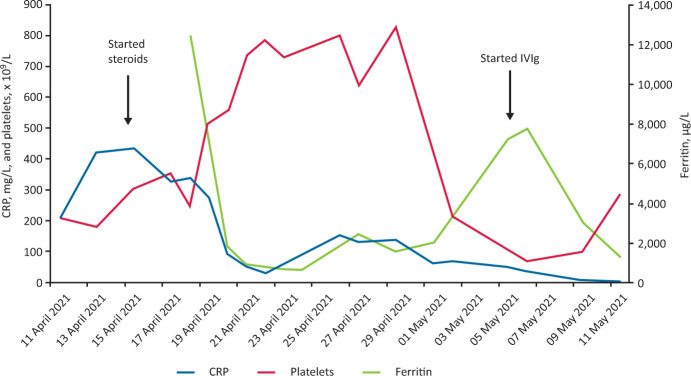

Given the features of fever, hepatosplenomegaly, hyperferritinaemia, coagulopathy and pericarditis in the absence of evidence for infection or malignant disease, a presumptive diagnosis of a multi-system inflammatory disorder secondary to recent COVID-19 vaccination was made. Pulsed intravenous (IV) methylprednisolone (1 g/day for 3 consecutive days) was started followed by high-dose oral prednisolone (60 mg once daily). Her temperature, pulse and respiratory rate normalised within 12 hours of initiating steroids and concurrent symptomatic and biochemical improvements were observed (Fig 1).

Fig 1.

Changes in C-reactive protein, platelets and ferritin during admission. CRP = C-reactive protein; Ig = immunoglobulins; IV = intravenous.

However, 6 days later her fever resumed, and she developed a thrombocytopenia (platelets of 70 × 109/L). Repeat septic screen was negative. Bone marrow biopsy showed a reactive picture. A 5-day course of IV immunoglobulins was initiated that resulted in resolution of her fever and improvement in her myalgia and chest pain. The patient was discharged home after 33 days to continue her recovery on a weaning course of oral prednisolone.

Discussion

Haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a rare syndrome of acute and rapidly progressive systemic inflammation characterised by cytopenias, excessive cytokine production and hyperferritinaemia.1 Abnormal activation of pro-inflammatory cytokines results in the over-activation and proliferation of macrophages, hypersecretion of cytokines (predominantly interleukin (IL) 1, IL-6 and tumour necrosis factor alpha) termed the ‘cytokine storm’, and phagocytosis of haematopoietic cells within the bone marrow.2 This results in the clinical constellation of fever, lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly and multi-organ failure.2 Diagnosis is challenging as it presents as a non-specific illness and mimics sepsis. The condition is classified as primary or secondary. Primary (familial) HLH is a rare condition caused by genetic mutations that presents in childhood. Secondary HLH is the more common form in adulthood. Known triggers include viral infections (CMV, EBV and SARS-CoV-2), malignancy, autoimmune disorders (eg adult-onset Still's disease and systemic lupus erythematosus) and drugs.2

Several differing diagnostic criteria to define HLH exist; however, these were largely developed around paediatric populations.3 The diagnostic H score was developed from a cohort of patients with secondary HLH and our patient fulfilled a diagnosis of HLH using this tool.4 Therapeutic options outlined by HLH treatment protocol include steroids, etoposide, cyclosporin, immunoglobulins and biologics such as IL-1 inhibitors (anakinra) and IL-6 inhibitors (tocilizumab).5 Prognosis of HLH is poor with a high mortality, particularly malignancy-associated HLH.5

In this patient, her symptoms developed within days of the Oxford–AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccination suggesting a potential causal link. It was reported via the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency COVID-19 Yellow Card system.6 An alternative disease trigger was not identified despite thorough investigation. In particular, no evidence for active or prior SARS-CoV-2 infection was identified, although antibody tests were not performed.

The ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine uses a modified adenovirus ChAdOx1 as a viral vector to introduce the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein to cells, inducing an antibody and T-cell mediated response. The frequently reported self-limiting adverse reactions include injection-site tenderness, pyrexia, fatigue, myalgia and arthralgia.7 It has been linked to rare severe cerebral venous sinus thrombosis occurring in conjunction with low platelets and this is believed to be an immune phenomenon.7 HLH secondary to vaccination is rare but reported in adults following influenza vaccination.8,9 Following literature review, one case report of HLH post-COVID-19 vaccination was identified in a patient following an inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccination.10 Similar to our case, symptoms developed rapidly following vaccination, however, unlike our case they improved with dexamethasone alone and required no further treatment.10

Conclusion

This case prompts awareness among clinicians of HLH as a potentially serious complication of COVID-19 vaccination. However, with over 4.9 billion doses administered worldwide to date, this remains an extremely rare complication and should not discourage individuals from vaccination.

References

- 1.Retamozo S, Brito-Zerón P, Sisó-Almirall A, et al. Haemophagocytic syndrome and COVID-19. Clin Rheumatol 2021;40:1233–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Soy M, Atagündüz P, Atagündüz I, Sucak GT. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: a review inspired by the COVID-19 pandemic. Rheumatol Int 2021;41:7–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Henter JI, Horne A, Aricó M, et al. HLH-2004: Diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2007;48:124–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fardet L, Galicier L, Lambotte O, et al. Development and validation of the HScore, a score for the diagnosis of reactive hemophagocytic syndrome. Arthritis Rheumatol 2014;66:2613–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.La Rosée P, Horne A, Hines M, et al. Recommendations for the management of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in adults. Blood 2019;133:2465–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. Coronovirus Yellow Card reporting site. MHRA. https://coronavirus-yellowcard.mhra.gov.uk [Google Scholar]

- 7.Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. Summary of Product Characteristics for Vaxzevria. MHRA, 2021. www.gov.uk/government/publications/regulatory-approval-of-covid-19-vaccine-astrazeneca/information-for-healthcare-professionals-on-covid-19-vaccine-astrazeneca [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ikebe T, Takata H, Sasaki H, et al. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis following influenza vaccination in a patient with aplastic anemia undergoing allogeneic bone marrow stem cell transplantation. Int J Hematol 2017;105:389–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liederman Z, Behl P. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis associated with adult vaccination: a case of cytokine flurries. Canadian Journal of General Internal Medicine 2015;10:39–42. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tang LV, Hu Y. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis after COVID-19 vaccination. J Hematol Oncol 2021;14:87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]