Abstract

Introduction

Strategies are needed to increase implementation of evidence-based tobacco dependence treatment (TDT) in health care systems in low-and middle-income countries (LMICs).

Aims and Methods

We conducted a two-arm cluster randomized controlled trial to compare the effectiveness of two strategies for implementing TDT guidelines in community health centers (n = 26) in Vietnam. Arm 1 included training and a tool kit (eg, reminder system) to promote and support delivery of the 4As (Ask about tobacco use, Advise to quit, Assess readiness, Assist with brief counseling) (Arm 1). Arm 2 included Arm 1 components plus a system to refer smokers to a community health worker (CHW) for more intensive counseling (4As + R). Provider surveys were conducted at baseline, 6 months, and 12 months to assess the hypothesized effect of the strategies on provider and organizational-level factors. The primary outcome was provider adoption of the 4As.

Results

Adoption of the 4As increased significantly across both study arms (all p < .001). Perceived organizational priority for TDT, compatibility with current workflow, and provider attitudes, norms, and self-efficacy related to TDT also improved significantly across both arms. In Arm 2 sites, 41% of smokers were referred to a CHW for additional counseling.

Conclusions

The study demonstrated the effectiveness of a multicomponent and multilevel strategy (ie, provider and system) for implementing evidence-based TDT in the Vietnam public health system. Combining provider-delivered brief counseling with opportunities for more in-depth counseling offered by a trained CHW may optimize outcomes and offers a potentially scalable model for increasing access to TDT in health care systems like Vietnam.

Implications

Improving implementation of evidence-based TDT guidelines is a necessary step toward reducing the growing burden of noncommunicable diseases and premature death in LMICs. The findings provide new evidence on the effectiveness of multilevel strategies for adapting and implementing TDT into routine care in Vietnam and offer a potentially scalable model for meeting Framework Convention on Tobacco Control Article 14 goals in other LMICs with comparable public health systems. The study also demonstrates that combining provider-delivered brief counseling with referral to a CHW for more in-depth counseling and support can optimize access to evidence-based treatment for tobacco use.

Clinical trials number: NCT01967654.

Introduction

According to the 2015 Global Adult Tobacco Survey, 45% of adult men in Vietnam are current smokers.1 Progress toward the World Health Organization’s (WHO) 2025 goals of reducing tobacco-related mortality tobacco use by 30% will require accelerating full implementation of the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC).2,3

The FCTC is a global treaty that outlines evidence-based policies and programs for tobacco control. This includes Article 14, which requires Parties to implement effective strategies to provide access to treatment for tobacco dependence.3 There is strong evidence that asking all patients about tobacco use, advising smokers to quit, assessing readiness to quit, and offering cessation assistance (eg, additional counseling and/or pharmacotherapy) (ie, 4As) can significantly increase smoking abstinence.4–6 Yet progress in implementing Article 14 has been slow, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).7,8

Barriers to integrating tobacco dependence treatment (TDT) in primary care settings include the low political priority placed on TDT, the lack of funding, and the associated lack of health care system capacity and infrastructure to support and facilitate routine screening and delivery of tobacco cessation services.9,10

A growing literature supports the effectiveness of strategies for overcoming barriers to implementing TDT guidelines in primary care settings.11–17 Alerts and clinical decision support, as well as offering clinicians an opportunity to delegate more intensive counseling by providing an option to refer patients to a smoking cessation telephone Quitline, can increase adoption of TDT guidelines and patient access to evidence-based cessation support.13–17 However, most of these studies were conducted in high-income countries (HICs), and there is little guidance on how to adapt evidence-based interventions to local culture and context in low-resource, primary care settings.

This paper presents outcomes from Vietnam Quits (VQuit), the first cluster randomized controlled trial to compare the effectiveness of two multicomponent implementation strategies for increasing adoption of guideline-recommended TDT in community-based health care centers (CHCs) in an LMIC.18 The strategies included training and a tool kit vs training, tool kit, and a referral system that offered the option of referring patients to a community health worker (CHW) for multisession counseling. CHWs are effective in delivering and increasing the reach of a range of health promotion, disease prevention, and treatment services in LMICs.19–22 However, there are few studies demonstrating the effectiveness of cessation support delivered by CHWs, and we are aware of only one study that tested a model that combined clinical and community-based public health services (eg, support from CHWs) to improve cessation outcomes.22–27 This study provides evidence for an integrated model of care that leveraged Vietnam’s primary care infrastructure and CHW workforce to increase access to guideline-recommended TDT.

Methods

Study Setting

This VQuit study was conducted in CHCs located in Thai Nguyen province which is in a rural region north of the Vietnam capital, Hanoi. The public health system in Vietnam consists of four administrative levels: national, provincial/municipal, district, and commune (ie, community). CHCs serve as the primary access point for public health and preventive care in Vietnam. Each CHC is staffed by 5–6 health care providers and, depending on the commune population, supported by 8–10 CHWs. CHWs implement national public health programs and ensure that CHC patients are adhering to treatment and prevention plans.

Study Design

From 2015 to 2018, we conducted a two-arm cluster randomized controlled trial in which 26 CHCs were randomized to one of two multicomponent implementation strategies to enhance adoption of guideline-recommended TDT.18,28 Arm 1 included provider training and a tool kit with patient educational brochures and materials that changed the practice environment (ie, 4As poster, desktop clinical decision support, documentation system) to remind and support providers to deliver and document the 4As: Ask (Screen for tobacco use), Advise to quit, Assess readiness to quit, and Assist (offer brief counseling and provide patient brochures). Arm 2 included Arm 1 components plus a system for providers to refer patients to a trained CHW to receive three sessions of manual-guided, in-person cessation counseling (ie, 4As + R). The intervention period was 12 months. We hypothesized that the package of implementation strategies available in arms 1 and 2 would improve provider norms and attitudes toward TDT and increase self-efficacy at 12 months post intervention compared with baseline in both study arms. We further hypothesized that at 12 months post intervention, increases in organizational priority, perceived organizational support, and compatibility with workflow would be greater in Arm 2 compared with Arm 1.29,30

Site Eligibility and Recruitment

CHCs were selected from two districts in Thai Nguyen Province (Pho Yen and Dai Tu District). CHCs were eligible if they had at least one physician, >4 allied health care professional staff (nurses and midwives), >5 CHWs, and a patient population of at least 6000. The Director of the District Health Centers (who oversees the CHCs) introduced the study to all CHCs that met these criteria through a letter and follow-up telephone or in-person contacts. Among those expressing interest, we enrolled 26 CHCs in three successive waves (8 in the first and third waves, 10 in the second). Within each wave, half of the CHCs were assigned to each arm using simple random assignment.

Study Conditions

Through a formative assessment and iterative process that was guided by the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR),30,31 we adapted existing evidence-based tobacco cessation training curricula and guideline implementation strategies (ie, training and practice changes), which had been tested in HICs, for use in the context of the Vietnamese health care system.13–17 CFIR posits that effective implementation is influenced by multilevel factors across five domains: inner setting (eg, compatibility, resources, and leadership), intervention characteristics (eg, complexity), individual characteristics (eg, provider self-efficacy), outer setting factors (eg, policy), and the implementation process.30 Barriers and facilitators were identified across the CFIR domains and informed the adaptation of the implementation strategies to the local context.31–33 For example, the lack of an electronic charting system resulted in the design of a poster in exam rooms to serve as a reminder to deliver the 4As, a desktop flip chart that provided point-of-care clinical decision support, and a paper form to document the 4As. This process was conducted in partnership with the Ministry of Health, District Health leadership, and frontline health care workers.

Arm 1 (Training and Tool Kit to Promote 4As)

All health care providers working in study sites in both study arms attended a two-day training informed by the Association for the Treatment of Tobacco Use and Dependence core competencies and the WHO Tobacco Control Package for Building Capacity for Tobacco Control in primary care.34,35 The training aimed to increase knowledge about the consequences of tobacco use and build self-efficacy and skills needed to deliver the 4As. CHCs in different arms received separate trainings. Three months after the start of the intervention, we conducted a one-day booster training for all providers. The tool kit materials included patient brochures, the poster, desktop flip chart, and the documentation system.

Arm 2 (Arm 1 + Referral to CHW [4As + R])

Providers in Arm 2 received the Arm 1 training and tool kit. In addition, they were trained to use the paper referral system to facilitate referrals to the CHWs. We selected 6–8 CHWs per CHC to serve as counselors. Details about CHW eligibility criteria are published elsewhere.28

CHWs attended a 4-day training that included all of the components in the provider training plus more in-depth training in motivational interviewing, cognitive behavioral skills building approaches (eg, identifying triggers, coping strategies), and how to use the 3-session manual and fidelity tracking tool.36,37 The manual was culturally adapted to a rural, general population of Vietnamese smokers with guidance from a theoretical framework for improving cultural appropriateness of behavior change programs.38 During their weekly visit to the CHCs, CHWs picked up referral forms that were completed by CHC providers and contacted smokers who had agreed to receive CHW counseling. CHWs called patients within five days of their CHC visit to schedule the first in-person counseling session. The details of the session content are described in a previous publication.28

Measures and Data Collection

The primary outcome was defined as provider adoption of the 4As or 4As + R. This was measured with cross-sectional patient exit interviews (PEIs) conducted immediately after the visit at baseline and at 12 months.39,40 At each time point, consecutive patients were screened in the waiting room to assess eligibility which included current tobacco use (past 7-day use of waterpipe and/or cigarettes), age ≥ 18, and visiting the CHC for a routine patient visit. Eligible patients were then asked if they would be willing to complete a PEI immediately after their visit. The type of smoker was assessed with two questions that asked patients the number of cigarettes smoked per day and the amount of waterpipe usage per day. If a patient reported one or more cigarettes smoked per day and no waterpipe use per day, they were coded as a “cigarette only” smoker. Similarly, if patients reported no cigarette use per day but used a waterpipe one or more times per day, they were coded as a “waterpipe only” smoker. Dual smokers were patients who reported one or more cigarettes per day and smoking waterpipe one or more times a day.

To assess provider adoption of the 4As + R, the PEI asked patients whether during their visit the provider asked if they currently used cigarettes and/or waterpipe, asked if they were ready to quit, advised them to quit, offered brief counseling to help them quit smoking cigarettes and/or waterpipe, and were offered a referral for additional counseling. Patients responded either yes or no.

We conducted surveys with all health care providers in each CHC at baseline, 6 months, and 12 months to assess changes in provider attitudes, self-efficacy, and norms related to TDT, organizational priority, compatibility (fit), and perceived organizational support to deliver TDT.29,30,41 Response options were based on a 4-point Likert scale: 1—strongly disagree, 2—disagree, 3—agree, and 4—strongly agree. This research was approved by the New York University School of Medicine and Institute for Social and Medical Studies Institutional Review Boards.

Analysis

Patient Exit Interviews

We analyzed PEIs from 2679 tobacco users across all three waves: 1372 from the pre-intervention period and 1307 from the post-intervention period (Table 1). We used descriptive statistics to summarize the patient characteristics by arm in the pre- and post-intervention periods. Table 1 presents data from both time periods because we used a cross-sectional design; patients were not necessarily the same at each time point. We compared categorical characteristics using chi-squared tests. We compared cigarette and waterpipe use per day using a negative binomial mixed regression with patients nested within commune and randomly varying intercepts. Small differences in patient education were observed between arms; therefore, education was included as a covariate in analysis of the primary outcome, provider adoption of TDT guidelines.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Patients Who Completed Patient Exit Interviews Pre- and Post-Intervention, By Arm

| Pre-intervention | Post-intervention | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arm 1 n = 672 | Arm 2 n = 700 | Arm 1 n = 649 | Arm 2 n = 658 | |

| Type of tobacco user, n (%) | ||||

| Cigarette only | 263 (39.1) | 247 (35.3) | 251 (38.7) | 233 (35.4) |

| Waterpipe only | 138 (20.5) | 170 (24.3) | 140 (21.6) | 167 (25.4) |

| Dual | 271 (40.3) | 283 (40.4) | 258 (39.8) | 258 (39.2) |

| Age* | ||||

| 17-34 | 112 (16.7) | 119 (17.0) | 111 (17.1) | 143 (21.7) |

| 35-44 | 108 (16.1) | 105 (15.0) | 123 (19.0) | 126 (19.1) |

| 45-64 | 351 (52.2) | 375 (53.6) | 323 (49.8) | 311 (47.3) |

| 65+ | 101 (15.0) | 101 (14.4) | 92 (14.2) | 78 (11.9) |

| Education* † | ||||

| Primary or less | 64 (9.5) | 103 (14.7) | 65 (10.0) | 68 (10.3) |

| Secondary | 328 (48.8) | 379 (54.1) | 319 (49.2) | 385 (58.5) |

| High School | 168 (25.0) | 166 (23.7) | 153 (23.6) | 129 (19.6) |

| College/Vocational | 112 (16.7) | 52 (7.4) | 112 (17.3) | 76 (11.6) |

| Income* | ||||

| <50 000 000 VND | 154 (22.9) | 157 (22.4) | 197 (30.4) | 219 (33.3) |

| 50 000 000-100 000 000 VND | 163 (24.3) | 196 (28.0) | 225 (34.7) | 216 (32.8) |

| >100 000 000 VND | 147 (21.9) | 147 (21.0) | 221 (34.1) | 213 (32.4) |

| Missing | 208 (31.0) | 200 (28.6) | 6 (0.9) | 10 (1.5) |

| Cigarettes per daya. Mean (SD) | 11.8 (9.3) | 10.8 (7.7) | 11.4 (9.4) | 10.0 (8.6) |

| Waterpipe per dayb, Mean (SD)* | 15.3 (12.4) | 15.8 (13.0) | 13.7 (13.2) | 14.1 (11.9) |

aVND = Vietnamese Dong.

aCigarettes per day includes dual users’ and excludes waterpipe users.

bWaterpipe use per day includes dual users’ daily waterpipe use and excludes cigarette users.

†Significant difference by arm.

*Significant difference by time.

To compare the odds of provider adoption of TDT guidelines in the pre- and post-intervention periods, we used a generalized linear mixed-effects model (GLMM), with patients nested within one of 26 communes, randomly varying intercepts, and patient education as a covariate. We also used a GLMM to compare the odds of provider adoption of TDT guidelines in the post-intervention period across cigarette only, waterpipe only, and dual smokers. Intraclass correlations were estimated using a resampling method described by Chakraborty and Sen.42

Provider Surveys

All providers in the CHCs (n = 162) who completed a baseline, 6-month, or 12-month survey were included. Responses to questions about attitudes, norms, and self-efficacy were grouped into these three constructs based on item analysis: nine items in the attitudes construct, three items in norms, and three items in self-efficacy. We converted the value of each individual item from a 1–4 scale to a 0–100 scale. The scales were then scored as the percent of maximum possible.43 Finally, a GLMM was used to examine change in provider attitudes from baseline to 6- and 12-month follow-ups. The lme4 package of the R statistical computing environment was used for all mixed regression analyses.44,45 The emmeans R package was used to estimate contrasts for GLMMs.46 All tests of statistical significance were two-tailed, and p < .05 was considered significant.

Responses to three individual questions about inner setting constructs (ie, perceived organizational priority and organizational support, and TDT compatibility with routine practice) were dichotomized into two categories, agree or disagree. We conducted chi-square analysis to compare baseline and 12 months responses to these items by arm.

Results

Table 1 presents the characteristics of the two cross-sectional samples of patients completing the PEIs by period (pre- and post-intervention) and by arm. The type of tobacco used by the sample of patients completing the PEIs did not vary significantly between the pre- and post-periods or by arm. Most of the participants were dual smokers followed by cigarette-only smokers. The pre- and post-intervention patient populations differed by age, income, education, and level of waterpipe use. Education was the only patient characteristic that differed by arm. This difference was observed at both time points.

CHC and provider characteristics did not differ significantly by arm (data not shown). Providers’ mean age was 40, 71% were female, 15% were physicians, 46% physician assistants, and 16% nurses. CHCs did not differ significantly by number of providers (all had one MD), number of patients, or types of services delivered. The interclass correlations for each of the 4As and Refer ranged from 0.12 to 0.45 (Estimates and CI available on request).

Table 2 presents patient-reported provider adoption of TDT guidelines in the pre- and post-intervention periods by study arm. Mixed-effects regression models showed that the odds of patients being asked about tobacco, assessed for readiness to quit, advised to quit, and assisted with brief counseling were all substantially higher in the post-intervention period (all p < .001) in both arms. For Ask, Advise, and Assess outcomes, arm by time interaction effects were not significant. Arm by time interaction effects for Assist and Refer could not be estimated given zero patients assisted or referred in at least one arm during the pre-intervention period. When compared with Arm 1, providers in Arm 2 were less likely to offer TDT, particularly assistance with brief counseling, but this difference did not reach significance (p = .08). Therefore, there was no difference in delivery of the 4As by arm. In Arm 2 CHCs, 41% of patients were referred to a CHW for more intensive counseling.

Table 2.

Change in Adoption of Tobacco Dependence Treatment by Arm and Time

| Pre-intervention | Post-intervention | p | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arm 1 n = 672 n (%) | Arm 2 n = 700 n (%) | Arm 1 n = 649 n (%) | Arm 2 n = 658 n (%) | Arm effect during post-period | Pre vs. post period effect, combining Arms | |

| Ask | 77 (11.5) | 53 (7.6) | 544 (83.8) | 502 (76.3) | .240 | <.001 |

| Advise | 43 (6.4) | 23 (3.3) | 523 (80.6) | 492 (74.8) | .426 | <.001 |

| Assess | 7 (1.0) | 6 (0.9) | 486 (74.9) | 428 (65.0) | .301 | <.001 |

| Assist | 0 (0) | 1 (0.1) | 397 (61.2) | 301 (45.7) | .080 | <.001 |

| Refer | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0) | 7 (1.1) | 268 (40.7) | <.001 | <.001 |

Patient education is included as a covariate. Arm difference odds ratios (Ask = 0.61, Advise = 0.73, Assess = 0.63, Assist = 0.46, and Referral = 196). Time difference odds ratios (Ask = 51, Advise = 106, Assess = 429, Assist = 2592, and Referral = 991).

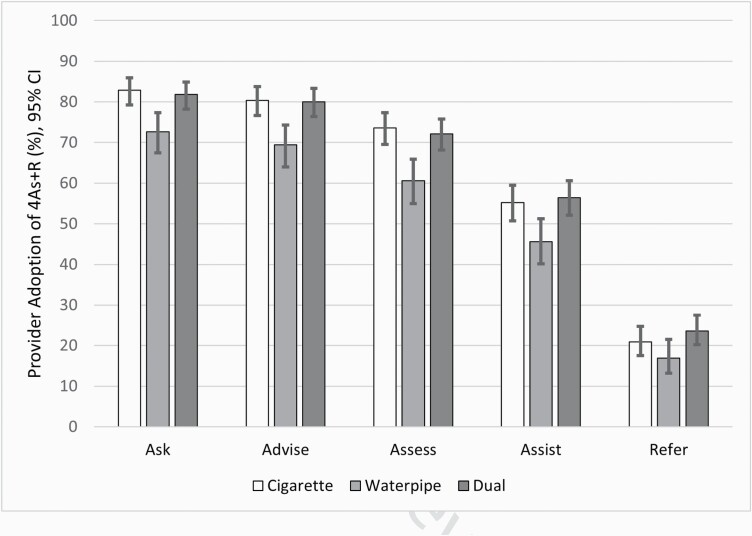

Figure 1 shows patient-reported provider adoption of TDT guidelines in the post period by type of smoker. There were no significant differences in receipt of the 4As by arm in the post-intervention period; therefore, the results described below were combined across arms. Receipt of the 4As was consistently lower for waterpipe-only users compared with cigarette-only and dual users. Based on the PEIs, when compared with cigarette-only and dual smokers, providers were less likely to engage in TDT behaviors when the patient only smoked waterpipe. Waterpipe-only smokers were less likely to be asked (OR = 0.70; CI: 0.49, 1.0; p = .05), advised (OR = 0.66; CI: 0.47, 0.94; p = .02), and counseled and/or referred to a CHW (OR = 0.70; CI: 0.50, 0.97; p = ·.03) compared with dual users and less likely to be assessed for readiness to quit compared with cigarette-only smokers (OR = 0.73; CI: 0.53, 1.0; p = .04). There were no significant differences in receipt of the 4As between cigarette and dual smokers.

Figure 1.

Patient-reported provider adoption of 4As + R post intervention by type of smoker. Abbreviation: 4As + R, Ask about tobacco use, Advise to quit, Assess readiness, Assist with brief counseling plus a system to refer smokers to a community health worker for more intensive counseling.

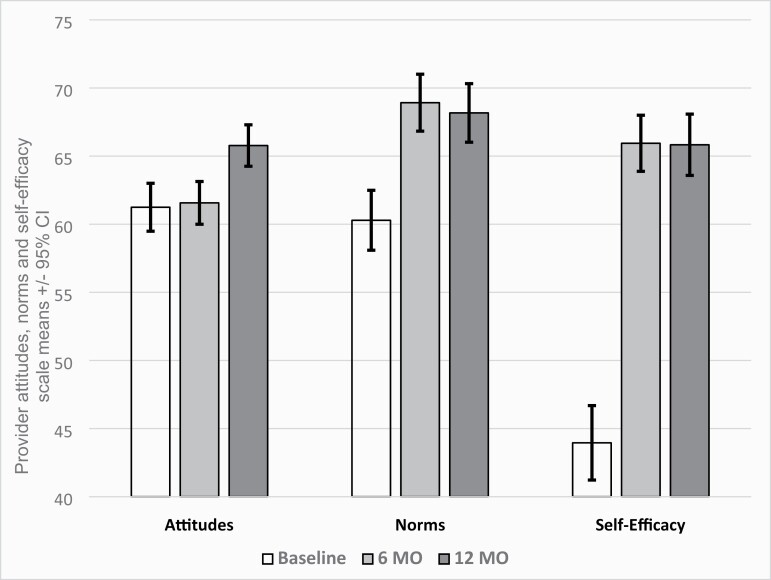

Figure 2 shows changes over time in provider-reported attitudes, norms, and self-efficacy. Because there were no arm differences at any point in time in provider-reported attitudes, norms, or self-efficacy, nor were there differences by study arm in the changes over time, we present the combined data across arms at each time point. All three constructs increased significantly by 12 months (p < .001).

Figure 2.

Change in provider-reported attitudes, norms, and self-efficacy.

Similarly, there were no arm differences at any point in time or in change over time in responses to provider perceptions about organization-level constructs. We, therefore, describe results of the aggregated data by arm at baseline and 12 months. At baseline, agreement with the statement “TDT is a top priority in this health center” increased from 49.4% at baseline to 79.3% at 12 months (p < .000). Agreement with the statement, “Helping patients quit smoking fits well into my routine practice,” increased from 76.2% to 86.2% (p < .001), and agreements with the statement, “Health care providers get the support they need to help patients stop smoking,” increased from 72.2% to 99.4% (p < .001).

Discussion

We found that a multicomponent, multilevel implementation strategy, which was aligned with Vietnam’s public health care delivery system infrastructure, and adapted to local context, resulted in significant increases in provider adoption of guideline-recommended TDT (ie, 4As) across both study arms. In Arm 2 study sites, 41% of smokers offered referral received an additional three sessions of counseling which, we showed in a prior publication, was associated with higher quit rates than brief provider counseling alone.28

Results from the longitudinal provider surveys provide some explanation for similar improvements in adoption of the 4As across arms. Providers in CHCs in both study arms reported similar increases in organizational priority for treating tobacco use, perceived organizational support to deliver TDT, and changes in norms, attitudes, and self-efficacy, a strong predictor of provider behavior change.47 Findings from the VQuit study’s post-intervention qualitative interviews support these survey findings.48 During those interviews, both providers and CHWs attributed training, particularly the skills building component, to their increased confidence to deliver cessation assistance. Additional took kit components were also described as enhancing confidence by offering point-of-care guidance and facilitating provider-patient communication about tobacco cessation.48 Based on the survey and qualitative data, training and system changes (eg, clinical decision support, reminder) created a context that elevated the importance of TDT and facilitated integration into routine care across all CHCs, including those that did not have the referral option.

Although the delivery of the 4As increased across all types of smokers, providers were less likely to offer cessation assistance to waterpipe smokers than to cigarette-only and dual smokers. The VQuit training included a module on the health consequences of waterpipe use, but persistent beliefs about the relative safety of waterpipe use compared with cigarettes may have influenced the variation in provider behavior across tobacco products. The known dangers of waterpipe use warrant updates in training and clinical guidelines to include recommendations for consistent screening and advice to quit for waterpipe and other harmful tobacco products.

A trained workforce is clearly a prerequisite for effectively disseminating and implementing TDT nationally. Yet, LMICs are less likely to report having TDT training programs compared with HICs.10 LMICs would benefit from technical assistance to adapt existing standards and curriculum to local languages and context rather than create new programs. VQuit funding provided this type of support which yielded a curriculum and a train-the-training (TTT) program that the Ministry of Health is integrating into their TDT training efforts. However, further investment is needed to facilitate the design of a sustainable and scalable infrastructure for training the full range of health professionals in LMICs. This may include virtual TTT programs to increase reach and reduce costs, and leveraging existing global health partnerships like the South East Asian Tobacco Control Alliance to optimize dissemination. Monitoring and evaluation of training programs are also needed to assess the optimal designs (eg, frequency of training, format), the affordability of different options, and the long-term impact on providers’ adoption of TDT guidelines.

Training alone, however, may not be sufficient to effect long-term change. VQuit’s approach was consistent with the implementation science literature that demonstrates the need to address contextual and individual provider-level barriers to achieve effective implementation and sustained guideline adoption.30,49 VQuit’s additional support systems, (ie, referral system), as well as other quality improvement approaches (eg, audit and feedback), not tested in this study, are effective in improving guideline-recommended care but are often lacking in LMIC primary care settings.14–17 For VQuit, we adapted the practice changes and materials to a paper-based system. However, this approach will change as information technology is increasingly integrated into primary care health care delivery settings in LMICs. Sustaining gains, and scaling Article 14 guidelines, will require ongoing resource allocation and partnerships with government and health care system stakeholders to continue to adapt TDT-related systems to incorporate emerging technologies. These changes will offer several advantages including facilitating monitoring and evaluation and the delivery of guideline-recommended care.

Sustaining and scaling evidence-based TDT will also be made easier if it is part of an integrated approach to noncommunicable disease (NCD) prevention and control in primary care settings. This is a WHO recommendation and one that was strongly endorsed by the CHC health care providers. Providers explained that the most effective method for sustaining the TDT program was to integrate it into other national public health priority programs, specifically in existing NCD programs.48 As a stand-alone program, TDT may gain little traction as political support as funding and health system infrastructure evolve to improve the prevention and treatment of chronic diseases.

Our study findings also contribute to a small but growing literature that supports the role of CHWs in reducing the burden of tobacco use and fills gaps in knowledge about effective models for implementing evidence-based TDT in LMICs with a public health system infrastructure similar to Vietnam’s.23–25,27 Specifically, the task sharing model, in which CHWs were trained as a clinic referral resource, resulted in over 1000 smokers receiving more intensive counseling.28 Moreover, compared with provider advice alone, the addition of CHW counseling resulted in a significant increase in 6 month biochemically validated abstinence rates (25.7% vs 10.5%, p < .001).28 These findings are consistent with a large body of literature that supports the added effect of in-depth counseling on tobacco abstinence compared with brief counseling.6,14,50 Referral resources, like the CHWs in VQuit, address the lack of time frequently reported by providers as a barrier to offering more than just brief advice to quit.32 However, this does not negate the role of providers and the primary care delivery system in promoting tobacco cessation by offering brief advice, an intervention that is effective in increasing quit rates and affordable across all country income levels.6 Rather, our study demonstrated an effective model for bridging the role of CHWs and the clinical delivery system to increase access to TDT and improve treatment outcomes.

Strategies and models for improving access to TDT will vary depending on the country context and available resources. For example, the WHO recommends integrating Quitline referral systems into primary care settings, but both CHWs and Quitlines offer a potentially sustainable and scalable means for ensuring wide access to tobacco cessation support for those who wish to quit and can extend the reach of treatment beyond the primary care setting. In 2015, after VQuit was implemented, Vietnam launched a national Quitline. This provides an opportunity to compare the reach and effectiveness of a CHW referral model with one that integrates Quitline referral systems in primary care settings and how cessation outcomes may vary depending on the population of tobacco users. LMICs are also being encouraged to implement mobile health or text messaging programs nationally. Again, monitoring systems are needed to generate policy and practice-relevant data to inform resource allocations across these options and to optimize both access to care and impact.

The study had several limitations. First, participants were limited to patients from CHCs in a rural province located north of Hanoi; however, these settings are relatively homogeneous through rural areas in Vietnam. Second, although the main outcome was based on patient self-report, as noted in the Methods section, patients were surveyed immediately after the visit reducing the risk of recall bias. Third, we were unable to analyze correlations between hypothesized mediators (eg, change in provider norms, attitudes, and self-efficacy) and outcomes because the identity of the provider that each patient visited was not recorded in PEIs. Fourth, the extremely low rates of adherence to guidelines at baseline (0%–7% for three of the 4 As) limited the ability to examine interactions between arm assignment and time. Fifth, contamination across sites could have been a limitation. However, arms 1 and 2 providers were trained separately so that CHCs assigned to Arm 1 were not aware of the Arm 2 referral option. In addition, the CHCs are located in geographically separate communities. Finally, we cannot comment on the individual contribution of each of the system changes and training as they were implemented as a package in both arms. However, the multicomponent strategy was theory-driven and consistent with implementation science literature which supports designing strategies that address individual and contextual factors that determine practice behavior and guideline adoption.

Conclusions

Our study demonstrated an effective multicomponent, multilevel strategy for translating evidence-based guidelines for TDT into routine care in public health care delivery systems in Vietnam and extending the reach of TDT beyond primary care to include community settings through CHW-delivered services. Support for LMICs to adapt TDT training and evidence-based system changes to local context, and integrating TDT into NCD programs, are important steps toward ensuring widespread access to treatment for those who wish to quit and achieving global targets for reducing tobacco-related morbidity and mortality.

Supplementary Material

A Contributorship Form detailing each author’s specific involvement with this content, as well as any supplementary data, are available online at https://academic.oup.com/ntr.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank Dr. Hai, Director of the Ministry of Health’s Tobacco Fund, and members of our Stakeholder Advisory Board for their invaluable input and feedback and for supporting this work.

Funding

This study was supported by National Cancer Institute (R01CA175329).

Declaration of Interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Data availability

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

- 1. World Health Organization. GATS Fact Sheet Viet Nam. https://www.who.int/tobacco/surveillance/survey/gats/VN-2015_FactSheet_Standalone_E_Oct2016.pdf?ua=1. Accessed August 3, 2021.

- 2. Beaglehole R, Bonita R, Horton R, et al. ; Lancet NCD Action Group; NCD Alliance . Priority actions for the non-communicable disease crisis. Lancet. 2011;377(9775):1438–1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. World Health Organization. FCTC Article 14 Guidelines. https://www.who.int/fctc/Guidelines.pdf. Accessed August 3, 2021.

- 4. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Smoking Cessation. A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fiore MC, Jaén CR, Baker TB, et al. . Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 6. West R, Raw M, McNeill A, et al. . Health-care interventions to promote and assist tobacco cessation: a review of efficacy, effectiveness and affordability for use in national guideline development. Addiction. 2015;110(9):1388–1403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nilan K, Raw M, McKeever TM, Murray RL, McNeill A. Progress in implementation of WHO FCTC Article 14 and its guidelines: a survey of tobacco dependence treatment provision in 142 countries. Addiction. 2017;112(11):2023–2031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Piné-Abata H, McNeill A, Murray R, Bitton A, Rigotti N, Raw M. A survey of tobacco dependence treatment services in 121 countries. Addiction. 2013;108(8):1476–1484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shelley DR, Kyriakos C, McNeill A, et al. . Challenges to implementing the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control guidelines on tobacco cessation treatment: a qualitative analysis. Addiction. 2020;115(3):527–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kruse GR, Rigotti NA, Raw M, et al. . Tobacco dependence treatment training programs: an International Survey. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;18(5):1012–1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Powell BJ, Waltz TJ, Chinman MJ, et al. . A refined compilation of implementation strategies: results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implement Sci. 2015;10:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Papadakis S, McDonald P, Mullen KA, Reid R, Skulsky K, Pipe A. Strategies to increase the delivery of smoking cessation treatments in primary care settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev Med. 2010;51(3–4):199–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Shelley D, Cantrell J. The effect of linking community health centers to a state-level smoker’s quitline on rates of cessation assistance. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fiore M, Adsit R, Zehner M, et al. . An electronic health record-based interoperable eReferral system to enhance smoking Quitline treatment in primary care. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2019;26(8–9):778–786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sheffer MA, Baker TB, Fraser DL, Adsit RT, McAfee TA, Fiore MC. Fax referrals, academic detailing, and tobacco quitline use: a randomized trial. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42(1):21–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Boyle R, Solberg L, Fiore M. Use of electronic health records to support smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;7(12):CD008743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bernstein SL, Weiss J, DeWitt M, et al. . A randomized trial of decision support for tobacco dependence treatment in an inpatient electronic medical record: clinical results. Implement Sci. 2019;14(1):8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shelley D, VanDevanter N, Cleland CC, Nguyen L, Nguyen N. Implementing tobacco use treatment guidelines in community health centers in Vietnam. Implement Sci. 2015;10:142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. WHO Guideline on Health Policy and System Support to Optimize CHW Programmes.https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/275501/WHO-HIS-HWF-CHW-2018.1-eng.pdf?ua=1. Accessed September 22, 2021.

- 20. Balcázar HG, de Heer HD. Community health workers as partners in the management of non-communicable diseases. Lancet Glob Health. 2015;3(9):e508–e509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jeet G, Thakur JS, Prinja S, Singh M. Community health workers for non-communicable diseases prevention and control in developing countries: evidence and implications. PLoS One. 2017;12(7):e0180640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sarkar BK, Shahab L, Arora M, Lorencatto F, Reddy KS, West R. A cluster randomized controlled trial of a brief tobacco cessation intervention for low-income communities in India: study protocol. Addiction. 2014;109(3):371–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Muramoto ML, Hall JR, Nichter M, et al. . Activating lay health influencers to promote tobacco cessation. Am J Health Behav. 2014;38(3):392–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Louwagie GM, Okuyemi KS, Ayo-Yusuf OA. Efficacy of brief motivational interviewing on smoking cessation at tuberculosis clinics in Tshwane, South Africa: a randomized controlled trial. Addiction. 2014;109(11):1942–1952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Begh RA, Aveyard P, Upton P, et al. . Promoting smoking cessation in Pakistani and Bangladeshi men in the UK: pilot cluster randomised controlled trial of trained community outreach workers. Trials. 2011;12:197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kumar MS, Sarma PS, Thankappan KR. Community-based group intervention for tobacco cessation in rural Tamil Nadu, India: a cluster randomized trial. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2012;43(1):53–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Thankappan KR, Mini GK, Hariharan M, Vijayakumar G, Sarma PS, Nichter M. Smoking cessation among diabetic patients in Kerala, India: 1-year follow-up results from a pilot randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(12):e256–e257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jiang N, Siman N, Cleland CM, et al. . Effectiveness of village health worker-delivered smoking cessation counseling in Vietnam. Nicotine Tob Res. 2019;21(11):1524–1530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1991;50(2):179–211. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4:50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. VanDevanter N, Kumar P, Nguyen N, et al. . Application of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research to assess factors that may influence implementation of tobacco use treatment guidelines in the Viet Nam public health care delivery system. Implement Sci. 2017;12(1):27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Shelley D, Tseng TY, Pham H, et al. . Factors influencing tobacco use treatment patterns among Vietnamese health care providers working in community health centers. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Shelley D, Nguyen L, Pham H, VanDevanter N, Nguyen N. Barriers and facilitators to expanding the role of community health workers to include smoking cessation services in Vietnam: a qualitative analysis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. World health Organization. Strengthening Health Systems for Treating Tobacco Use: Building Capacity for Tobacco Control. WHO Tobacco Control Package. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/strengthening-health-systems-for-treating-tobacco-dependence-in-primary-care. Accessed September 23, 2021.

- 35. Association for the Treatment of Tobacco Use and Dependence. 2018. https://www.attud.org/. Accessed May 21, 2021.

- 36. Miller WR, Rollnick S.. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People to Change Addictive Behaviors. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Marlatt GA, Gordon JR.. Relapse Prevention: Maintenance Strategies in the Treatment of Addictive Behaviors. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kreuter MW, Lukwago SN, Bucholtz RD, Clark EM, Sanders-Thompson V. Achieving cultural appropriateness in health promotion programs: targeted and tailored approaches. Health Educ Behav. 2003;30(2):133–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Pbert L, Adams A, Quirk M, Hebert JR, Ockene JK, Luippold RS. The patient exit interview as an assessment of physician-delivered smoking intervention: a validation study. Health Psychol. 1999;18(2):183–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Conroy MB, Majchrzak NE, Silverman CB, et al. . Measuring provider adoption to tobacco treatment guidelines: a comparison of electronic medical record review, patient survey, and provider survey. Nic Tob Research. 2005;7(Suppl 1):S35–S43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Francis JJ, Eccles MP, Johnston M, et al. . Explaining the effects of an intervention designed to promote evidence-based diabetes care: a theory-based process evaluation of a pragmatic cluster randomised controlled trial. Implement Sci. 2008;3:50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Chakraborty H, Sen PK. Resampling method to estimate intra-cluster correlation for clustered binary data. Commu Stat-Theor Methods. 2016;45(8):2368–2377. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Cohen P, Cohen J, Aiken LS, West SG. The problem of units and the circumstance for POMP. Multivariate Behav Res.1999;34(3):315–346. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bates D, Maechler M, Bolker B, Walker S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J Stat Softw. 2015;67(1):1–48. [Google Scholar]

- 45. R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2020. https://www.R-project.org/. Accessed September 23, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Russell L. 2020. emmeans: Estimated Marginal Means, aka Least-Squares Means. R package version 1.4.5. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=emmeans. Accessed September 23, 2021.

- 47. Godin G, Bélanger-Gravel A, Eccles M, Grimshaw J. Healthcare professionals’ intentions and behaviours: a systematic review of studies based on social cognitive theories. Implement Sci. 2008;3:36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. VanDevanter N, Vu M, Nguyen A, et al. . A qualitative assessment of factors influencing implementation and sustainability of evidence-based tobacco use treatment in Vietnam health centers. Implement Sci. 2020;15(1):73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Nilsen P, Bernhardsson S. Context matters in implementation science: a scoping review of determinant frameworks that describe contextual determinants for implementation outcomes. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Stead LF, Koilpillai P, Fanshawe TR, Lancaster T. Combined pharmacotherapy and behavioural interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;3:CD008286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.