Abstract

Background

Patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) are vulnerable to some psychological disorders. Here we describe the psychological impact of a COVID-19 pandemic lockdown in patients with IBD.

Methods

This multicenter prospective cohort study included 145 patients recently diagnosed with IBD. Data on clinical and demographic characteristics, anxiety and depression scales, and IBD activity were collected in two telephone surveys, during and after the first COVID-19 lockdown in Spain. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated.

Results

During lockdown, 33.1% and 24.1% scored high on the anxiety and depression scales, respectively. Independent factors related to anxiety (all values ORs; 95% CIs) during lockdown were female sex (2; 1.2–5.4) and IBD activity (4.3; 1.8–10.4). Factors related to depression were comorbidity (3.3; 1.1–9.8), IBD activity (6; 1.9–18.1), use of biologics (2.9; 1.1–7.6), and living alone or with one person (3.1; 1.2–8.2). After lockdown, anxiety and depression symptoms showed significant improvement, with 24.8% and 15.2% having high scores for anxiety and depression, respectively. Factors related to post-lockdown anxiety were female sex (2.5; 1.01–6.3), Crohn's disease (3.3; 1.3–8.5), and active IBD (4.1; 1.2–13.7). Factors associated with depression were previous history of mood and/or anxiety disorders (6.3; 1.6–24.9), active IBD (7.5; 2.1–26.8), and steroid use (6.4; 1.4–29).

Conclusions

Lockdown during the COVID-19 pandemic had a significant psychological impact in patients with IBD. Disease activity was related to the presence of anxiety and depression symptoms during and after lockdown.

Keywords: COVID-19, IBD, Anxiety, Depression

Abstract

Antecedentes

Los pacientes con enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal (EII) son vulnerables a sufrir trastornos psicológicos. En este estudio describimos el impacto psicológico que ha supuesto el confinamiento durante el COVID-19 en pacientes con EII.

Métodos

Este estudio de cohorte prospectivo multicéntrico se incluyeron 145 pacientes con diagnóstico de EII reciente. Los datos sobre las características clínicas y demográficas, las escalas de ansiedad y depresión y la actividad de la EII se recogieron en dos encuestas telefónicas, durante y después del primer confinamiento por COVID-19 en España. Se calcularon las odds ratios (OR) y los intervalos de confianza (IC) al 95%.

Resultados

Durante el confinamiento, el 33,1% y el 24,1% puntuaron alto en las escalas de ansiedad y depresión respectivamente. Los factores independientes relacionados con la ansiedad (todos los valores OR; IC del 95%) durante el confinamiento fueron el sexo femenino (2; 1,2-5,4) y la actividad de la EII (4,3; 1,8-10,4). Los factores relacionados con la depresión fueron la comorbilidad (3,3; 1,1-9,8), la actividad de la EII (6; 1,9-18,1), el uso de biológicos (2,9; 1,1-7,6) y el vivir solo o con una persona (3,1; 1,2-8,2). Tras el confinamiento, los síntomas de ansiedad y depresión mostraron una mejoría significativa, ya que el 24,8% y el 15,2% tenían puntuaciones altas en ansiedad y depresión, respectivamente. Los factores relacionados con la ansiedad tras el confinamiento fueron el sexo femenino (2,5; 1,01-6,3), enfermedad de Crohn (3,3; 1,3-8,5) y EII activa (4,1; 1,2-13,7). Los factores asociados con la depresión fueron los antecedentes de trastornos del estado de ánimo y/o de ansiedad (6,3; 1,6-24,9), EII activa (7,5; 2,1-26,8), y el uso de esteroides (6,4; 1,4-29).

Conclusiones

El confinamiento durante la pandemia de COVID-19 tuvo un impacto psicológico significativo en los pacientes con EII. La actividad de la enfermedad se relacionó con la presencia de síntomas de ansiedad y depresión durante y después del confinamiento.

Palabras clave: COVID-19, EII, Ansiedad, Depresión

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has triggered important changes in the lifestyle and behavior of the general population, with an inevitable impact on mental health.1, 2 Lockdown of the population at home is a widely used measure during incidence peaks. Some surveys during the first wave of lockdown have identified anxiety symptoms in 23–37% and depression symptoms in 24–46% of the general population.3, 4, 5

Patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) are vulnerable to some psychological disorders.6, 7 Although lockdown of a population with a comorbidity that makes them susceptible to infections can have protective effects, it can intensify their vulnerability to these disorders. Research is limited on the psychological impact of lockdown on the population with IBD. Available findings show a high prevalence of symptoms, but we do not know how much this psychological impact persists once lockdown ends.8, 9, 10

Our study aims were to assess the psychological impact of pandemic lockdown in patients with IBD and to evaluate factors related to the risk of developing anxiety and depression symptoms.

Patients and methods

Study population

We carried out a multicenter prospective study in a cohort of patients with IBD diagnosed during 2018 and 2019 in four hospitals in the Valencian community of Spain. These patients were participating in a prospective registry of new IBD cases. The inclusion criterion was diagnosis of Crohn's disease (CD) or ulcerative colitis (UC) according to ECCO/ESGAR guidelines (clinical evaluation and a combination of endoscopic, histological, radiological, and/or biochemical findings).11 The exclusion criteria were age under 18 years; diagnosis of unclassified colitis, intellectual disability, dementia, bipolar disorder, or schizophrenia; and the presence of a language barrier.

Ethical considerations

The Ethics Committee of HGUA-ISABIAL approved the study (PI 2020-078). All patients included in the study read the patient information sheet and signed the informed consent form sent by e-mail.

Sample size calculation

We estimated the sample size for the multiple logistic regression analysis using standard methods, assuming the need for at least 10 cases for each independent variable. The anxiety/depression rate during COVID-19 lockdown was estimated to be 35%, and 142 patients thus were required to perform a multiple logistic regression analysis with five independent variables.12

Data collection

We extracted clinical characteristics from electronic medical records. Body mass index and medication adherence were checked in telephone surveys. Patients were evaluated at diagnosis for anxiety and depression using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS).

Patients were contacted by telephone twice during the first wave of COVID-19 in Spain. The first contact was made between April 13 and May 17, 2020, during the last month of lockdown imposed by the Spanish government. The second telephone contact was made 2 months later, when the population had returned to its routines after a period of increasingly relaxed lockdown measures.

During lockdown, all patients were invited to answer questionnaires addressing anxiety and depression (HADS), IBD activity (the Modified Harvey Bradshaw Index [MHBI] for CD and Simple Clinical Colitis Activity Index [SCCAI] for CU),13, 14, 15 medical treatment, and work status. In addition, a semi-structured interview was conducted, covering demographic characteristics and characteristics of lockdown.

After lockdown, all patients were invited to answer the same questionnaires covering anxiety and depression (HADS) and IBD activity (MHBI, SCCAI) and to complete a semi-structured interview.

Definitions

Predictive variables

Age was dichotomized as <40 years and ≥40 years according to other studies of IBD. Regular alcohol use was defined as alcohol intake ≥3 times/week. Education level was split into low level (secondary school or lower) and high level (college or higher). The definition of active employment included being an employee or self-employed and excluded temporary employment or cessation of being self-employed.

Comorbidity was characterized as coexisting diseases or conditions that affect an individual's physiologic reserve condition or require chronic treatment. A previous history of mood and/or anxiety disorders (MAD) was defined as the presence of an active MAD diagnosis in the medical records within 6 months before lockdown. Psychopharmacological treatment was defined as active intake of benzodiazepines and/or antidepressants.

Disease phenotype was classified according to the Montreal classification.16 IBD was considered to be active when the MHBI or SCCAI score was ≥5.14, 15 Extra-intestinal manifestations of IBD were extracted from the confirmed diagnosis in medical records according to European Evidence-based Consensus on Extra-intestinal Manifestations in IBD.17 Medications for IBD treatment during the interviews were classified as mesalazine, steroids (prednisone or equivalent, budesonide and beclomethasone), immunosuppressants (azathioprine, mercaptopurine, methotrexate, and cyclosporine), biologics (infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, golimumab, ustekinumab, and vedolizumab), or small molecule inhibitors (tofacitinib).

Dependent variables

Symptoms of anxiety and depression were evaluated using HADS. The HADS-total consists of 14 items, divided into two 7-item subscales, one each for anxiety (HADS-A) and depression (HADS-D).13 Patients were considered to have a high anxiety or depression scale scores based on a cut-off value of >7 for the respective subscale.18

Outcomes

The primary aim of the study was to evaluate anxiety and depression symptoms in the early IBD population during and after the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown. We also evaluated factors related to the risk that these symptoms would be present.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to examine the baseline characteristics. Variables with a probable relation to the presence of anxiety and depression symptoms were evaluated during and after the lockdown by univariate regression. Variables with P < 0.05 in univariate analysis were included in a multivariable logistic regression model. The statistical significance level for all variables was set at P < 0.05. We used the SPSS statistical package for Windows, version 25.0.

Results

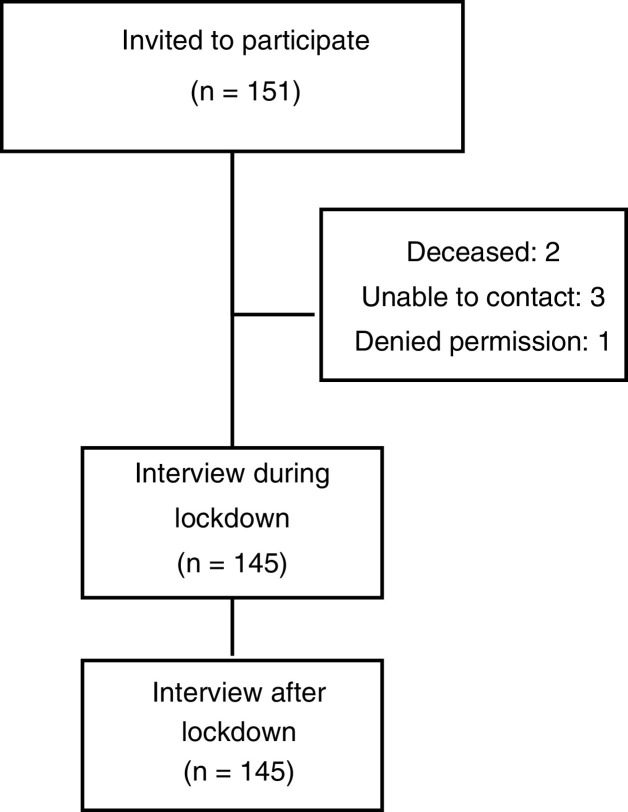

A total of 145 patients were included in the study (Fig. 1 ). All participants completed the two telephone surveys. Demographic and clinical characteristics during and after lockdown are shown in Table 1 .

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the study.

Table 1.

Clinical and demographic characteristics of the study population.

| During lockdown | After lockdown | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Male | 79 (54.5) | |

| Female | 66 (45.5) | |

| Age (mean in years, SD) | 43 (16.3) | |

| Disease type, n (%) | ||

| CD | 72 (49.7) | |

| UC | 73 (50.3) | |

| Duration of IBD, mean in months (SD) | 17.3 (6.4) | |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 25 (4.8) | |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 22 (15.2) | |

| Regular alcohol use, n (%) | 39 (26.9) | |

| Marital status | ||

| Married/partner, n (%) | 107 (73.8) | |

| Divorced, n (%) | 9 (6.2) | |

| Single, n (%) | 28 (19.3) | |

| Widowed, n (%) | 1 (0.7) | |

| Education, n (%) | ||

| Low level | 97 (66.9) | |

| High level | 48 (33.1) | |

| Active employment, n (%) | 52 (35.9) | 71 (49) |

| Comorbidity, n (%) | 69 (47.6) | |

| Previous history of MAD, n (%) | 15 (10.3) | |

| CD Montreal classification | 72 | |

| Age in years, n (%) | ||

| A2: 17–40 | 42 (58.3) | |

| A3: ≥40 | 30 (41.7) | |

| Location of Crohn's (>1 location possible), n (%) | ||

| L1: Ileal | 37 (51.4) | |

| L2: Colonic | 12 (16.7) | |

| L3: Ileocolonic | 22 (30.6) | |

| L4: Upper GI | 6 (8.3) | |

| Crohn's behavior, n (%) | ||

| B1: Inflammatory | 53 (73.6) | |

| B2: Stricturing | 11 (15.3) | |

| B3: Penetrating | 8 (11.1) | |

| Perianal involvement | 4 (5.6) | |

| UC Montreal classification, n (%) | 73 | |

| E1: Proctitis | 19 (26) | |

| E2: Distal colitis | 29 (39.7) | |

| E3: Total colitis | 25 (34.2) | |

| Active IBD, n (%) | 29 (20) | 18 (12.4) |

| EIM, n (%) | 23 (15.9) | |

| IBD-related surgical history, n (%) | 10 (6.9) | |

| Use of mesalazine, n (%) | 86 (59.3) | 86 (59.3) |

| Use of steroids, n (%) | 7 (4.8) | 12 (8.3) |

| Use of immunosuppressants, n (%) | 33 (22.8) | 32 (22.1) |

| Use of biologics, n (%) | 44 (30.3) | 46 (31.7) |

| Psychopharmacological treatment, n (%) | 29 (20) | |

| Cohabitants during lockdown (n) 0-1 | 55 (37.9) | |

| ≥2 | 90 (62.1) | |

CD, Crohn's disease; UC, ulcerative colitis; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; BMI, body mass index; MAD, mood and/or anxiety disorders; EIM, extra-intestinal manifestations; GI, gastrointestinal

Anxiety

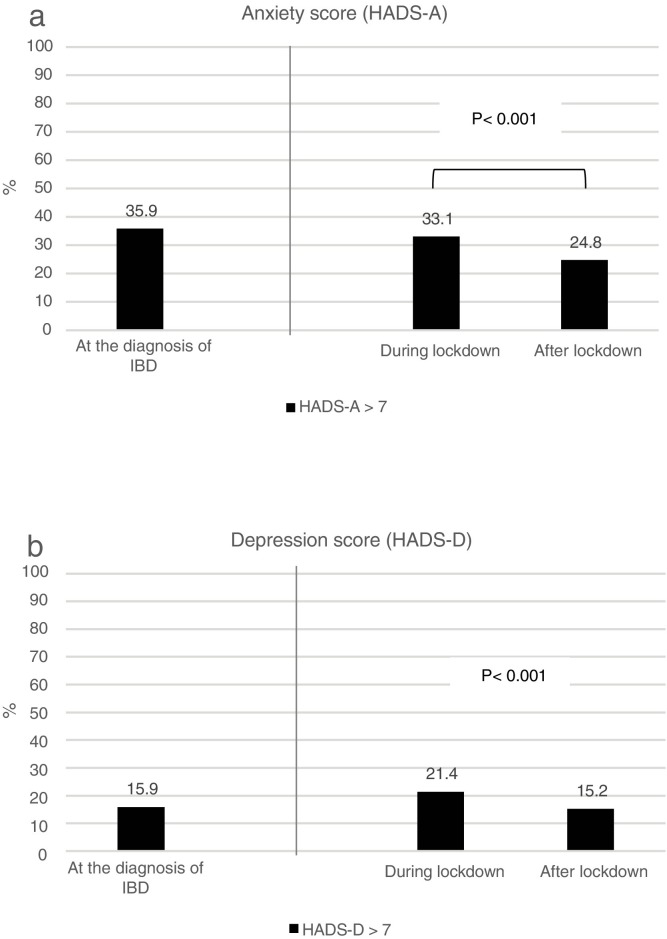

During lockdown, 48 (33.1%) patients had a high anxiety score (Fig. 2a ). The factors found in the univariate analysis to be predictive of anxiety during lockdown are shown in Table 2 . After multivariate analysis adjusted for all of the studied variables, female sex (odds ratio [OR], 2; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.2–5.4; P = 0.012) and active IBD (OR, 4.3; 95% CI, 1.8–10.4; P = 0.001) were independently associated with the presence of anxiety symptoms (Table 4).

Figure 2.

Categorization of symptoms based on Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) scores at diagnosis of IBD and during the course of lockdown. (2a) HADS-anxiety. (2b) HADS-depression.

Table 2.

Univariate analysis of risk factors for the presence of significant symptoms of anxiety during and after lockdown.

| During |

After |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HADS anxiety >7 | OR | 95% confidence interval | P | HADS anxiety >7 | OR | 95% confidence interval | P | |

| n (%) | n (%) | |||||||

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 18 (22.8) | 1 | 11 (13.9) | 1 | ||||

| Female | 30 (45.5) | 2.8 | 1.3–5.7 | 0.004 | 25 (37.9) | 3.7 | 1.6–8.4 | 0.001 |

| Age | ||||||||

| <40 years | 24 (35.8) | 1 | 17 (25.4) | 1 | ||||

| ≥40 years | 24 (30.8) | 0.79 | 0.39–1.5 | 0.519 | 19 (24.4) | 0.94 | 0.44–2 | 0.888 |

| Disease type | ||||||||

| CD | 29 (40.3) | 1.9 | 0.94–3.8 | 0.068 | 27 (37.5) | 4.2 | 1.8–9.9 | <0.001 |

| UC | 19 (26) | 1 | 9 (12.3) | 1 | ||||

| BMI | ||||||||

| <30 | 40 (32) | 1 | 30 (24) | 1 | ||||

| ≥30 | 8 (40) | 1.4 | 0.53–3.7 | 0.480 | 6 (30) | 1.3 | 0.47–3.8 | 0.564 |

| Current smoker | ||||||||

| Yes | 8 (36.4) | 1.1 | 0.46–3 | 0.724 | 6 (27.3) | 1.1 | 0.41–3.2 | 0.773 |

| No | 40 (32.5) | 1 | 30 (24.4) | 1 | ||||

| Regular alcohol use | ||||||||

| Yes | 15 (38.5) | 1.3 | 0.64–2.9 | 0.406 | 11 (28.2) | 1.2 | 0.55–2.9 | 0.568 |

| No | 33 (31.1) | 1 | 25 (23.6) | 1 | ||||

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Married/partner | 38 (35.5) | 0.64 | 0.28–1.7 | 0.301 | 26 (24.3) | 1 | ||

| Divorced/single/widowed | 10 (26.3) | 1 | 10 (26.3) | 1.1 | 0.47–2.5 | 0.805 | ||

| Education | ||||||||

| Low level | 33 (34) | 1.1 | 0.54–2.3 | 0.739 | 26 (26.8) | 1.3 | 0.6–3.1 | 0.434 |

| High level | 15 (31.1) | 1 | 10 (20.8) | 1 | ||||

| Active employment | ||||||||

| Yes | 16 (30.8) | 0.84 | 0.4–1.7 | 0.655 | 19 (26.8) | 1.2 | 0.57–2.2 | 0.598 |

| No | 32 (34.4) | 1 | 17 (23) | 1 | ||||

| Comorbidity | ||||||||

| Yes | 25 (36.2) | 1.3 | 0.65–2.6 | 0.446 | 20 (29) | 1.5 | 0.71–3.2 | 0.269 |

| No | 23 (30.3) | 1 | 16 (21.1) | 1 | ||||

| Previous history of MAD | ||||||||

| Yes | 8 (53.3) | 2.5 | 0.87–7.5 | 0.089 | 9 (60) | 5.7 | 1.8–17.4 | 0.001 |

| No | 40 (30.8) | 1 | 27 (20.8) | 1 | ||||

| Active IBD | ||||||||

| Yes | 18 (62.1) | 4.6 | 1.9–11 | <0.001 | 12 (66.7) | 8.5 | 2.9–25.1 | <0.001 |

| No | 30 (25.9) | 1 | 24 (18.9) | 1 | ||||

| EIM | ||||||||

| Yes | 10 (43.5) | 1.7 | 0.68–4.2 | 0.249 | 7 (30.4) | 1.4 | 0.52–3.7 | 0.497 |

| No | 38 (31.1) | 1 | 29 (23.8) | 1 | ||||

| IBD-related surgical history | ||||||||

| Yes | 3 (30) | 0.85 | 0.21–3.4 | 1 | 3 (30) | 1.3 | 0.32–5.4 | 0.71 |

| No | 45 (33.3) | 1 | 33 (24.4) | 1 | ||||

| Use of mesalazine | ||||||||

| Yes | 26 (30.2) | 0.72 | 0.36–1.4 | 0.375 | 18 (20.9) | 0.6 | 0.28–1.2 | 0.190 |

| No | 22 (37.7) | 1 | 18 (30.5) | 1 | ||||

| Use of steroids | ||||||||

| Yes | 3 (42.9) | 1.5 | 0.33–7.2 | 0.685 | 6 (50) | 3.4 | 1.03–11.4 | 0.073 |

| No | 45 (32.6) | 1 | 30 (22.6) | 1 | ||||

| Use of immunosuppressants | ||||||||

| Yes | 14 (42.4) | 1.6 | 0.76–3.7 | 0.195 | 10 (31.3) | 1.5 | 0.64–3.6 | 0.341 |

| No | 34 (30.4) | 1 | 26 (23) | 1 | ||||

| Use of biologics | ||||||||

| Yes | 15 (34.1) | 1.06 | 0.5–2.2 | 0.868 | 14 (30.4) | 1.5 | 0.69–3.3 | 0.287 |

| No | 33 (32.7) | 1 | 22 (22.2) | 1 | ||||

| Cohabitants during lockdown | ||||||||

| 0–1 | 23 (41.8) | 1.8 | 0.92–3.7 | 0.081 | 19 (34.5) | 2.2 | 1.05–4.8 | 0.034 |

| ≥2 | 25 (27.8) | 17 (18.9) | 1 | |||||

CD, Crohn's disease; UC, ulcerative colitis; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; BMI, body mass index; MAD, mood and/or anxiety disorders; EIM, extra-intestinal manifestations.

Table 4.

Risk factors independently associated with the presence of significant symptoms of anxiety and depression, during and after lockdown.

| Anxiety during lockdown |

Anxiety after lockdown |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted OR | 95% confidence interval | P | Adjusted OR | 95% confidence interval | P | |

| Sex: female | 2 | 1.2–5.4 | 0.012 | 2.5 | 1.01–6.3 | 0.047 |

| Disease type: CD | 3.3 | 1.3–8.5 | 0.010 | |||

| Previous history of MAD | 2.9 | 0.8–10.7 | 0.099 | |||

| Active IBD | 4.3 | 1.8–10.4 | 0.001 | 4.1 | 1.2–13.7 | 0.019 |

| Cohabitants during lockdown, 0-1 | 1.9 | 0.79–4.7 | 0.148 | |||

| Depression during lockdown |

Depression after lockdown |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted OR | 95% confidence interval | P | Adjusted OR | 95% confidence interval | P | |

| Sex: female | 2 | 0.79–5.5 | 0.134 | |||

| Comorbidity | 3.3 | 1.1–9.8 | 0.024 | |||

| Previous history of MAD | 0.98 | 0.21–45 | 0.98 | 6.3 | 1.6–24.9 | 0.008 |

| Active IBD | 6 | 1.9–18.1 | 0.001 | 7.5 | 2.1–26.8 | 0.002 |

| Use of steroids | 6.4 | 1.4–29 | 0.015 | |||

| Use of biologics | 2.9 | 1.1–7.6 | 0.031 | |||

| Cohabitants during lockdown, 0-1 | 3.1 | 1.2–8.2 | 0.017 | 2.2 | 0.71–6.9 | 0.170 |

CD, Crohn's disease; UC, ulcerative colitis; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; BMI, body mass index; MAD, mood and/or anxiety disorders; EIM, extra-intestinal manifestations.

After lockdown, 36 (24.8%) patients had a high anxiety score, which was a significant improvement from the proportion during lockdown (Fig. 2a). Factors found in univariate analysis to be predictive of anxiety after lockdown are shown in Table 2. After multivariate analysis adjusted for all of the studied variables, female sex (OR, 2.5; 95% CI, 1.01–6.3; P = 0.047), Crohn's disease (OR, 3.3; 95% CI, 1.3–8.5; P = 0.010), and active IBD (OR, 4.1; 95% CI, 1.2–13.7; P = 0.019) were independently associated with the presence of anxiety symptoms (Table 4).

Depression

During lockdown, 31 (24.1%) patients had a high depression score (Fig. 2b). The factors found in the univariate analysis to be predictive of depression during lockdown are shown in Table 3 . After multivariate analysis adjusted for all of the studied variables, comorbidity (OR, 3.3; 95% CI, 1.1–9.8; P = 0.024), active IBD (OR, 6; 95% CI, 1.9–18.1; P = 0.001), use of biologics (OR, 2.9; 95% CI, 1.1–7.6; P = 0.031), and living alone or with one person (OR, 3.1; 95% CI, 1.2–8.2; P = 0.017) were independently associated with the presence of depression symptoms (Table 4 ).

Table 3.

Univariate analysis of risk factors for the presence of significant symptoms of depression during and after lockdown.

| During |

After |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HADS depression >7 | OR | 95% confidence interval | P | HADS depression >7 | OR | 95% confidence interval | P | |

| n (%) | n (%) | |||||||

| Sex | ||||||||

| Men | 11 (13.9) | 1 | 9 (11.4) | 1 | ||||

| Women | 20 (30.3) | 2.6 | 1.1–6.13 | 0.017 | 13 (19.7) | 1.9 | 0.75–4.7 | 0.165 |

| Age | ||||||||

| <40 years | 10 (14.9) | 1 | 8 (9) | 1 | ||||

| ≥40 years | 21 (26.9) | 2.1 | 0.9–4.8 | 0.079 | 16 (20.5) | 2.6 | 0.96–7.1 | 0.053 |

| Disease type | ||||||||

| CD | 19 (26.4) | 1.8 | 0.81–4.1 | 0.144 | 15 (20.8) | 2.4 | 0.9–6.5 | 0.059 |

| UC | 12 (16.4) | 1 | 7 (9.6) | 1 | ||||

| BMI | ||||||||

| <30 | 25 (20) | 1 | 19 (15.2) | 1 | ||||

| ≥30 | 6 (30) | 1.7 | 0.59–4.9 | 0.377 | 3 (15) | 0.98 | 0.26–3.6 | 1 |

| Current smoker | ||||||||

| Yes | 4 (18.2) | 0.79 | 0.24–2.5 | 0.786 | 1 (4.5) | 0.23 | 0.02–1.8 | 0.189 |

| No | 27 (22) | 1 | 21 (17.1) | 1 | ||||

| Regular alcohol use | ||||||||

| Yes | 10 (25.6) | 1.3 | 0.58–3.3 | 0.448 | 9 (23.1) | 2.1 | 0.83–5.5 | 0.108 |

| No | 21 (19.8) | 1 | 13 (12.3) | 1 | ||||

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Married/partner | 20 (18.7) | 1 | 18 (16.8) | 1 | ||||

| Divorced/single/widowed | 11 (28.9) | 1.7 | 0.75–4.1 | 0.185 | 4 (10.5) | 0.58 | 0.18–1.8 | 0.353 |

| Education | ||||||||

| Low level | 24 (24.7) | 1.9 | 0.76–4.8 | 0.160 | 18 (18.6) | 2.5 | 0.79–7.8 | 0.106 |

| High level | 7 (14.6) | 1 | 4 (8.3) | 1 | ||||

| Active employee | ||||||||

| Yes | 8 (15.4) | 0.55 | 0.22–1.3 | 0.188 | 7 (9.9) | 0.43 | 0.16–1.1 | 0.081 |

| No | 23 (24.7) | 1 | 15 (20.3) | 1 | ||||

| Comorbidity | ||||||||

| Yes | 22 (31.9) | 3.4 | 1.4–8.2 | 0.003 | 14 (20.3) | 2.1 | 0.84–5.5 | 0.102 |

| No | 9 (11.8) | 1 | 8 (10.5) | 1 | ||||

| Previous history of MAD | ||||||||

| Yes | 8 (53.3) | 5.3 | 1.7–16.1 | 0.004 | 7 (46.7) | 6.7 | 2.1–21.1 | 0.002 |

| No | 23 (17.7) | 1 | 15 (11.5) | 1 | ||||

| Active IBD | ||||||||

| Yes | 14 (48.3) | 5.4 | 2.2–13.2 | <0.001 | 11 (61.1) | 16.5 | 5.3–51.3 | <0.001 |

| No | 17 (14.7) | 1 | 11 (8.7) | |||||

| EIM | ||||||||

| Yes | 6 (26.1) | 1.3 | 0.48–3.8 | 0.582 | 5 (21.7) | 1.7 | 0.56–5.2 | 0.348 |

| No | 25 (20.5) | 1 | 17 (13.9) | |||||

| IBD-related surgical history | ||||||||

| Yes | 3 (30) | 1.6 | 0.39–6.7 | 0.446 | 3 (30) | 2.6 | 0.62–11 | 0.178 |

| No | 28 (20.7) | 1 | 19 (14.1) | |||||

| Use of mesalazine | ||||||||

| Yes | 16 (18.6) | 0.67 | 0.3–1.4 | 0.325 | 11 (12.8) | 0.64 | 0.25–1.5 | 0.334 |

| No | 15 (25.4) | 1 | 11 (18.6) | 1 | ||||

| Use of steroids | ||||||||

| Yes | 2 (28.6) | 1.5 | 0.27–8.1 | 0.642 | 7 (58.3) | 11 | 3.1–39.1 | <0.001 |

| No | 9 (21.0) | 1 | 15 (11.3) | 1 | ||||

| Use of immunosuppressants | ||||||||

| Yes | 9 (27.3) | 1.5 | 0.62–3.7 | 0.347 | 5 (15.6) | 1.04 | 0.35–3 | 1 |

| No | 22 (19.6) | 1 | 17 (15) | 1 | ||||

| Use of biologics | ||||||||

| Yes | 14 (31.8) | 2.3 | 1.01–5.2 | 0.043 | 10 (21.7) | 2 | 0.79–5 | 0.133 |

| No | 17 (16.8) | 1 | 12 (12.1) | 1 | ||||

| Cohabitants during lockdown | ||||||||

| 0–1 | 18 (32.7) | 2.8 | 1.2–6.5 | 0.009 | 14 (25.5) | 3.5 | 1.3–9 | 0.007 |

| ≥2 | 13 (14.4) | 1 | 8 (8.9) | |||||

CD, Crohn's disease; UC, ulcerative colitis; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; BMI, body mass index; MAD, mood and/or anxiety disorders; EIM, extra-intestinal manifestations.

After lockdown, 22 (15.2%) patients had a high depression score, which was a significant improvement from the proportion during lockdown (Fig. 2b). Factors found in the univariate analysis to be predictive of depression after lockdown are shown in Table 4. After multivariate analysis adjusted for all of the studied variables, a previous history of MAD (OR, 6.3; 95% CI, 1.6–24.9; P = 0.008), active IBD (OR, 7.5; 95% CI, 2.1–26.8; P = 0.002), and use of steroids (OR, 7.5; 95% CI, 2.1–26.8; P = 0.015) were independently associated with the presence of depressive symptoms (Table 4).

Discussion

Our results show that a high proportion of patients with IBD suffered anxiety and depression during lockdown and that this proportion significantly decreased after lockdown ended. Factors associated with anxiety were mainly IBD activity and female sex, whereas factors associated with depression were more variable, with an important influence of IBD activity.

In an international public health emergency such as the COVID-19 pandemic, it is important to investigate the psychological impact on vulnerable populations such as patients with IBD.6, 7 Knowledge of this effect could lead to interventions to reduce the impact. Several studies have evaluated what the pandemic and the lockdown have meant in terms of mental health in the general population.1, 2, 3, 4, 5 However, few studies have assessed mental health effects during and after lockdown in a pandemic among patients with specific chronic diseases that may leave them feeling more threatened and at higher risk.

Here we report symptoms of depression and anxiety in relation to pandemic COVID-19 lockdown in a population with IBD. The proportion with symptoms during lockdown was similar to proportions found immediately after the IBD diagnosis, another moment of special vulnerability. Although the proportion of patients with anxiety and depression during lockdown was high, it is similar to that found in the general population during this period and lower than reported from other surveys of patients with IBD.6, 7, 8, 9 The divergence can be explained by the fact that our interviews were targeted to specific individuals, which avoided biases involved with an open survey offered to anyone who would participate and who may have different motivations for doing so. Therefore, this choice avoided a selection bias that can affect studies relying on online web-based surveys made generally available. Another possible explanation is that our study was focused on a population with chronic disease confined to their homes, with the majority of people not going out to work during lockdown. This situation may have favored a sense of security in patients with IBD who would likely perceive that they have a higher risk of infection and worse evolution of COVID-19 disease, as some surveys have suggested.10, 19

We found a significant decrease in symptoms of anxiety and depression after lockdown. This important finding suggests that the psychological consequences of lockdown among people with IBD might not be persistent, as has been shown in the general population and health workers after Wuhan eased its lockdown.20

In the general population, during a lockdown, women seem to have experienced more mental health difficulties than men, particularly in relation to anxiety and certain sleep disorders, such as insomnia.3, 4, 21, 22 In our study, female sex was a consistent risk factor for anxiety during and after lockdown. This finding is worth considering for patients with IBD. The differences between men and women in the development of depression symptoms seemed to have been minimal in our cohort, as previously described in the general population during lockdown.3, 22

A factor more consistently associated with both anxiety and depression in this study was disease activity. We have shown an important relationship between IBD activity and anxiety and depression during the COVID-19 pandemic. This effect of disease activity on anxiety and depression has been extensively described in IBD before this outbreak.7, 23 The existence of IBD activity in the context of a lockdown together with a blockade of the health system could be important in the development of symptoms of mental health conditions.10, 19 The effect of disease activity persisted after lockdown, emphasizing an important role for this factor in the presence of mental health symptoms.

Factors independently associated with depression during lockdown were more variable and included comorbidity, use of biologics, and living alone or with only one person during lockdown. Patients may have not been able to gain proper care from the health system because of the lockdown or have had a lack of social support in this context. High-quality social connections with friends and family members are associated with a reduced likelihood of depression, and being under a stay-at-home order has been previously associated with greater health anxiety, financial worry, and loneliness.22, 24 However, after lockdown, factors associated with depression were those commonly found in IBD, such as disease activity or previous MAD, showing that the situation quickly resolved for many participants once lockdown ended.

A potential limitation of the study is that the assessment was made through phone interviews. This method of contact could have led participants to give answers that they thought might be socially desired rather than reflecting their true feelings, especially in the case of men, who often find it harder to express feelings they perceive as weakness.25 However, disease activity using these phone questionnaires has been validated in the context of IBD.26, 27 Moreover, our sample is not fully representative of the whole population of patients with IBD because they all had a recent diagnosis and were closely followed up in specific IBD units. Strengths of our study are that it did not rely on a general online survey made available to the target population. Instead, each patient with a recent diagnosis was personally contacted, allowing us to avoid the selection bias of including only those who were motivated to respond.

In summary, our findings indicated that in an IBD population in highly stressful situations, such as an international public health emergency and lockdown, vulnerability to mental health conditions should be especially considered, particularly in women and in patients with active disease.

Funding

This work was supported by Instituto de Salud Carlos III (PI 18/01547) and the SVPD-Sociedad Valenciana de Patología Digestiva (Becas-2019).

Author contributions

Conception and design: LS, PB, CvH and MTRC Development of methodology: LS, PB, AG, JC, RL, MFG, MA,RJ, and MTRC. Acquisition of data: LS and PB Analysis and interpretation of data: LS, PZ, and CvH. Writing, review and/or revision of the manuscript: all authors. Study supervision: RJ and PZ.

Conflicts of interest

Laura Sempere declares that there is no conflict of interest.

Purificación Bernabeu declares that there is no conflict of interest.

José Cameo declares that there is no conflict of interest.

Ana Gutierrez declares that there is no conflict of interest.

Raquel Laveda declares that there is no conflict of interest.

Mariana Fe García declares that there is no conflict of interest.

Maríam Aguas declares that there is no conflict of interest.

Rodrigo Jover declares that there is no conflict of interest.

Pedro Zapater declares that there is no conflict of interest.

María Teresa Ruíz-Cantero declares that there is no conflict of interest.

Carlos van-der Hofstadt declares that there is no conflict of interest.

We thank Natalia Canales, Laura Sellés, and Laura Muñoz for help in recruiting and interviewing patients.

Writing assistance was provided by SF edits and paid by a grant.

The manuscript, including related data, figures and tables has not been previously published and that the manuscript is not under consideration elsewhere.

References

- 1.Ren X., Huang W., Pan H., Huang T., Wang X., Ma Y. Mental health during the Covid-19 outbreak in China: a meta-analysis. Psychiatr Q. 2020;91:1033–1045. doi: 10.1007/s11126-020-09796-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vindegaard N., Benros M.E. COVID-19 pandemic and mental health consequences: systematic review of the current evidence. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;89:531–542. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gualano M.R., Lo Moro G., Voglino G., Bert F., Siliquini R. Effects of COVID-19 lockdown on mental health and sleep disturbances in Italy. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:1–13. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17134779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Planchuelo-gómez Á., Odriozola-gonzález P., Jesús M., Luis-garcía De R. Longitudinal evaluation of the psychological impact of the COVID-19 crisis in Spain. J Affect Disord. 2020;277:842–849. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Qian M., Wu Q., Wu P., Hou Z., Liang Y., Cowling B.J., et al. Anxiety levels, precautionary behaviours and public perceptions during the early phase of the COVID-19 outbreak in China: a population-based cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open. 2020;10:1–10. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-040910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Graff L.A., Walker J.R., Bernstein C.N. Depression and anxiety in iflammatory bowel disease: a review of comorbidity and management. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:1105–1118. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neuendorf R., Harding A., Stello N., Hanes D., Wahbeh H. Depression and anxiety in patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: a systematic review. J Psychosom Res. 2016;87:70–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2016.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al Sulais E., Mosli M., Alameel T. The psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic on physicians in Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional study. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2020;26:249–255. doi: 10.4103/sjg.SJG_174_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trindade I.A., Ferreira N.B. COVID-19 pandemic's effects on disease and psychological outcomes of people with inflammatory bowel disease in Portugal: a preliminary research. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/ibd/izaa261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zingone F., Siniscalchi M., Savarino E.V., Barberio B., Cingolani L., D́Incà R., et al. Perception of the COVID-19 pandemic among patients with inflammatory bowel disease in the time of telemedicine: cross-sectional questionnaire study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22 doi: 10.2196/19574. e19574.p9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maaser C., Sturm A., Vavricka S.R., Kucharzik T., Fiorino G., Annese V., et al. ECCO-ESGAR guideline for diagnostic assessment in IBD Part 1: initial diagnosis, monitoring of known IBD, detection of complications. J Crohn's Colitis. 2019;13:144–164. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjy113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang C., Pan R., Wan X., Tan Y., Xu L., Ho C.S., et al. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17 doi: 10.3390/ijerph17051729. 1729.p25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stern A.F. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Occup Med (Chic Ill) 2014;64:393–394. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqu024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Evertsz’ F.B., Hoeks C.C.M.Q., Nieuwkerk P.T., Stokkers P.C., Ponsioen C.Y., Bockting C.L., et al. Development of the patient harvey bradshaw index and a comparison with a clinician-based harvey bradshaw index assessment of Crohn's disease activity. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2013;47:850–856. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31828b2196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walmsley R.S., Ayres R.C.S., Pounder R.E., Allan R.N. A simple clinical colitis activity index. Gut. 1998;43:29–32. doi: 10.1136/gut.43.1.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Silverberg M.S., Satsangi J., Ahmad T., Arnott I.D., Bernstein C.N., Brant S.R., et al. Toward an integrated clinical, molecular and serological classification of inflammatory bowel disease: report of a Working Party of the 2005 Montreal World Congress of Gastroenterology. Can J Gastroenterol. 2005;19SupplA doi: 10.1155/2005/269076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harbord M., Annese V., Vavricka S.R., Allez M., Barreiro-de Acosta M., Boberg K.M., et al. The first european evidence-based consensus on extra-intestinal manifestations in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohn's Colitis. 2016;10:239–254. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjv213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bernstein C.N., Zhang L., Lix L.M., Graff L.A., Walker J.R., Fisk J.D., et al. The validity and reliability of screening measures for depression and anxiety disorders in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24:1867–1875. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izy068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.D’Amico F., Rahier J., Leone S., Peyrin-Biroulet L., Danese S. Views of patients with inflammatory bowel disease on the COVID-19 pandemic: a global survey. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5:631–632. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30131-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lu P., Li X., Lu L., Zhang Y. The psychological states of people after Wuhan eased the lockdown. PLOS ONE. 2020;15:1–12. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0241173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bigalke J.A., Greenlund I.M., Carter J.R. Sex differences in self-report anxiety and sleep quality during COVID-19 stay-at-home orders. Biol Sex Differ. 2020;11:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s13293-020-00333-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tull M.T., Edmonds K.A., Scamaldo K.M., Richmond J.R., Rose J.P., Gratz K.L. Psychological outcomes associated with stay-at-home orders and the perceived impact of COVID-19 on daily life. Psychiatry Res. 2020;289 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113098. 113098.p6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nahon S., Lahmek P., Durance C., Olympie A., Lesgourgues B., Colombel J.F., et al. Risk factors of anxiety and depression in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:2086–2091. doi: 10.1002/ibd.22888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Werner-Seidler A., Afzali M.H., Chapman C., Sunderland M., Slade T. The relationship between social support networks and depression in the 2007 National Survey of Mental Health and Well-being. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2017;52:1463–1473. doi: 10.1007/s00127-017-1440-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deng Y., Chang L., Yang M., Huo M., Zhou R. Gender differences in emotional response: inconsistency between experience and expressivity. PLOS ONE. 2016;11:1–12. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0158666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Echarri A., Vera I., Ollero V., Arajol C., Riestra S., Robledo P., et al. The Harvey-Bradshaw index adapted to a mobile application compared with in-clinic assessment: the MediCrohn study. Telemed e-Health. 2020;26:80–88. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2018.0264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Higgins P.D.R., Schwartz M., Mapili J., Zimmermann E.M. Is endoscopy necessary for the measurement of disease activity in ulcerative colitis? Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:355–361. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.40641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]