Abstract

Understanding how individual beliefs and societal values influence support for measures to prevent SARS-CoV-2 transmission is vital to developing and implementing effective prevention policies. Using both Just World Theory and Cultural Dimensions Theory, the present study considered how individual-level justice beliefs and country-level social values predict support for vaccination and quarantine policy mandates to reduce SARS-CoV-2 transmission. Data from an international survey of adults from 46 countries (N = 6424) were used to evaluate how individual-level beliefs about justice for self and others, as well as national values—that is, power distance, individualism, masculinity, uncertainty avoidance, long-term orientation, and indulgence—influence support for vaccination and quarantine behavioral mandates. Multilevel modeling revealed that support for vaccination and quarantine mandates were positively associated with individual-level beliefs about justice for self, and negatively associated with country-level uncertainty avoidance. Significant cross-level interactions revealed that beliefs about justice for self were associated more strongly with support for mandatory vaccination in countries high in individualism, whereas beliefs about justice for others were more strongly associated with support for vaccination and quarantine mandates in countries high in long-term orientation. Beliefs about justice and cultural values can independently and also interactively influence support for evidence-based practices to reduce SARS-CoV-2 transmission, such as vaccination and quarantine. Understanding these multilevel influences may inform efforts to develop and implement effective prevention policies in varied national contexts.

Keywords: COVID-19, Vaccination, Quarantine, Just world beliefs, Values, Cultural dimensions

Implications.

Practice: Individual-level beliefs about justice may impact SARS-CoV-2 vaccination and quarantine, though effects will vary depending on national context.

Policy: Interventions to promote vaccination and quarantine can be multilevel and should simultaneously consider individual-level and national-level factors.

Research: Future research should aim to develop and tailor justice-oriented intervention to varied national contexts, as well as identify additional opportunities for multilevel interventions.

INTRODUCTION

Evidence-based behavioral prevention strategies are important in limiting transmission of SARS-CoV-2, the virus responsible for COVID-19 [1]. As of late 2020, behavioral prevention includes utilization of safe and effective vaccinations that are increasingly accessible in many nations [2]. Behavioral mitigation strategies also include quarantining in cases of known SARS-CoV-2 infection, or when there is confirmed or suspected close contact with infected persons [3]. Although vaccination and quarantine can both reduce virus transmission, efficacy hinges on the willingness of individuals and groups to engage in these prevention practices. Yet, encouraging uptake of vaccination and quarantine may be challenging [4]. Understanding how individual-level beliefs affect these recommended practices therefore may be vital to developing and implementing effective prevention policies. Simultaneously, incidence and response to COVID-19 varies considerably across nations, highlighting a potential role of higher-order cultural values [5, 6]. Presently, we consider whether receptivity to mandated COVID-19 vaccination and quarantine is predicted by individual-level beliefs about justice—specifically, the expectations individuals have about how they and others should be treated. We also consider whether support for COVID-19 vaccination and quarantine depends on national climate.

We are guided by arguably the most prominent psychological theory of justice, just world beliefs (JWB) [7]. According to JWB theorizing, humans have a preconscious need to believe the world is fair, which can afford a sense of control and provide a psychological coping resource in a world that, objectively, is often uncontrollable. However, belief strength also varies as a result of socialization and life experience, resulting in individual differences in JWB. Individual differences in JWB are also multifaceted, as people are guided both by their belief that the world treats others fairly (JWB-Other) and the belief that the world treats the self fairly (JWB-Self). Whereas JWB-Self is associated with adaptive personal health and well-being outcomes [8], JWB-Other predicts social callousness such as derogating and blaming innocent victims [9], including negative attitudes toward others’ health and well-being [10]. The COVID-19 pandemic poses a threat to JWB that may implicate both of these individual difference tendencies. Individuals with strong JWB-Self may be more likely to respond to opportunities to reassert control, including by endorsing vaccination and quarantine mandates. Conversely, individuals with strong JWB-Other may reassert control by endorsing socially callous attitudes, and by rationalizing that others deserve their negative outcomes. Accordingly, they may be less likely to endorse behavioral mandates that diminish the role of others’ personal responsibilities.

Support for vaccination and quarantine mandates may also depend on culture. Like justice, culture is routinely evaluated as a multidimensional construct, whereby collectives of people can be distinguished according to shared sets of social values [11]. One values structure that is particularly relevant to SARS-CoV-2 transmission is national values [12, 13]. Hofstede characterized national values along six cultural dimensions: (a) Power distance, encompassing cultural preference for hierarchy and acceptance of class and power inequality; (b) Individualism vs. collectivism, defining the degree of social group integration from immediate family (individualistic) to extended families, or to members of one’s in-group (collectivistic); (c) Uncertainty avoidance, encasing preferences for coping with uncertainty through social disapproval, rules, and laws; (d) Masculinity vs. femininity, encompassing cultural preferences for more stereotypically masculine (e.g., assertiveness, competitiveness, gender role division) versus feminine (caring, sympathy, and equality) attributes; (e) Long-term vs. short-term orientation, defining cultural preferences for adaptability and pragmatism (long-term) versus tradition and adherence to norms (short-term); and (f) Indulgence vs. restraint, defining cultural endorsements to fulfill personal desires (indulgence) versus controlling gratification (restraint) [11]. Of present interest, national values can impact health behavior by guiding public policies and adherence to social norms [14, 15], and Hofstede’s values may be particularly useful in exploring cross-national differences in receptivity to preventive health behavior policies and services [15]. Indeed, a nascent literature has linked Hofstede’s values to COVID-19 beliefs and behavior [5, 6, 16, 17]. For example, Gokmen et al. found that power distance was negatively associated with the rate of increase in COVID-19 infection, whereas individualism was positively associated [16]. Similarly, Huynh found that uncertainly avoidance was associated with greater use of social distancing [5]. However, a hitherto overlooked possibility is that national values could also modify the effects of individual-level beliefs on endorsement of COVID-19 prevention policies. We especially focus on cross-level moderator relationships given the available justice literature, which has demonstrated that higher-order justice climates are linked to culture and can modify the effects of individual-level justice beliefs, including on indices of personal well-being that parallel COVID-19 prevention behavior [18].

In the present study, we use data provided by the PsyCorona project—a large cross-national COVID-19 study—to consider how justice beliefs and national values independently and interactively predict support for vaccination and quarantine policies to reduce SARS-CoV-2 transmission. To the extent that support for prevention policies may reflect concern for one’s own health, we expected that beliefs about justice for self would be positively associated with support for mandatory vaccination and quarantine, whereas beliefs about justice for others would be negatively associated. We also considered whether cultural values would predict support for assertive vaccination and quarantine policies when considered alongside justice beliefs. Given a nascent literature connecting cultural values to COVID-19 outcomes, our consideration of cultural values was largely exploratory. Accordingly, our general working hypothesis was that cultural factors would impact support for vaccination and quarantine policy mandates through both main effects and moderator relationships with individual-level justice beliefs.

METHOD

Participants

This study was performed using data obtained from convenience samples recruited by the PsyCorona survey—a multinational collaborative study developed in response to the COVID-19 pandemic (https://psycorona.org/). As its overarching aim, PsyCorona seeks to study the psychological factors underlying responses to COVID-19 and associated public health measures (see Supplementary Material for detailed description). We used measures that were collected during wave 6 of PsyCorona, which was conducted May 9–16, 2020. Countries with n < 5 were excluded due to requirements of subsequently described multilevel modeling, resulting in a final sample size of 6424 participants from 46 countries. Supplementary Tables S1 and S2 report individual-level sociodemographic characteristics and within-country sample sizes, respectively.

Measures

JWB-Self and JWB-Other were each assessed using two items rated on a seven-point Likert scale (−3 = Strongly Disagree, 3 = Strongly Agree); “I feel that I/people get what I/they deserve” and “I feel that people treat me/each other fairly in life.” These items were adapted from a cross-culturally validated individual difference measure that includes evaluation of both distributive and procedural justice for self and others [19]. Two separate composites were calculated by averaging items for JWB-Self (r = .50, p < .001) and JWB-Other (r = .41, p < .001). In addition to individual-level sociodemographic variables, we used a self-report frequency measure available in wave 6 to covary for coronavirus exposure. This measure was calculated as the number of people in each participants’ social network who had been infected with SARS-CoV-2 (see Supplementary Table S1). This variable was included as a covariate given the potential for SARS-CoV-2 infection rates to differ across countries and within local contexts, both of which may be reflected in one’s individual social network exposure.

Mandatory vaccination and quarantine support were each assessed by a single item—“I would sign a petition that supports mandatory vaccination once a vaccine has been developed for coronavirus” and “I would sign a petition that supports mandatory quarantine for those that have coronavirus and those that have been exposed to the virus.” Both items were rated on a seven-point Likert type scale (−3 = Strongly Disagree, 3 = Strongly Agree). Means, SD, and bivariate associations for all individual-level Likert measures are presented in Supplementary Table S3. Mandatory vaccination and quarantine items were moderately correlated (r = .50, p < .01).

National values for included countries were represented using a recent publicly available assessment of Hofstede’s cultural dimensions (www.hofstede-insights.com). As aims for assessing national values were exploratory, we evaluated each of the six cultural dimensions, which were scored on a scale that ranges from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating greater levels of the initially listed (i.e., reference) value (e.g., masculinity vs. femininity). Means, standard deviations, bivariate associations, and within-country scores for each cultural dimension are presented in Supplementary Tables S2 and S3.

Statistical analysis

Individual and country-level influences on support for mandatory vaccination and quarantine were examined using stepwise multilevel regression with the nlme package in R v3.6.2. Separate multilevel regressions were conducted for vaccination and quarantine support. At the first step of both regressions, we included fixed effects for individual-level JWB main effects and covariates, and random effects for the model intercept and the JWB slopes. Given between-country variation, individual-level variables were group-mean centered. At the second step, we introduced country-level cultural values main effects and their cross-level interactions with JWB-Self and JWB-Other. We used likelihood ratio tests to assess improved model fit between steps. To aid interpretation, country-level cultural values were grand mean centered and rescaled (divided by 10). Significant interactions were probed using regions of significance [20].

RESULTS

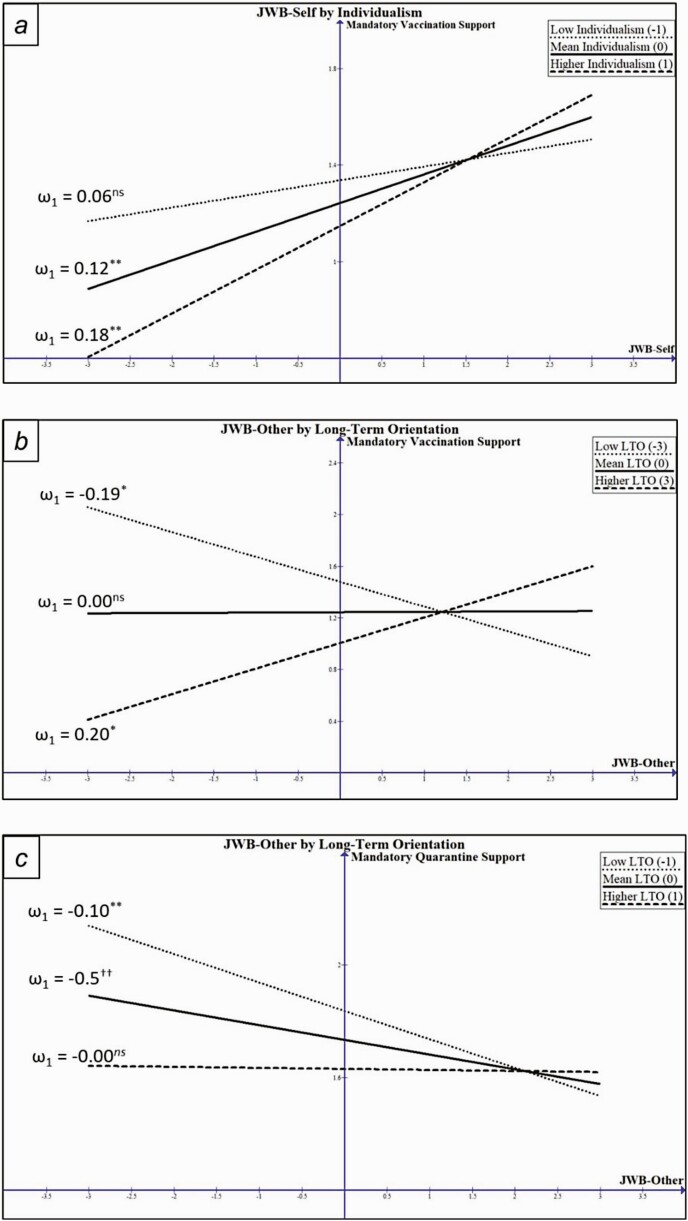

Table 1 presents multilevel regression results. For vaccination support, the intraclass correlation coefficient indicated that 10% of the variance was due to differences between countries. Adding country-level main and interactive effects improved model fit, χ 2(18) = 35.510, p < .01. Of primary interest, there were significant main effects of JWB-Self (b = 0.119, p < .01) and uncertainty avoidance (b = −0.113, p = .01). Additionally, we observed significant JWB-Self × individualism (b = 0.062, p = .02) and JWB-Other × long-term orientation (b = 0.065, p = .02) cross-level interactions. JWB-Self was more strongly associated with support for mandatory vaccination in countries higher in individualism (Fig. 1a), whereas JWB-Other was negatively associated with support for mandatory vaccination in countries lower in long-term orientation, but was positively associated in higher long-term orientation countries (Fig. 1b).

Table 1.

Multilevel regression coefficients predicting support for mandatory vaccination and quarantine

| Mandatory vaccination | Mandatory quarantine | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Country level | Baseline | Country level | |||||

| Estimate | SE | Estimate | SE | Estimate | SE | Estimate | SE | |

| Fixed effects | ||||||||

| Intercept | 1.21** | 0.12 | 1.24** | 0.10 | 1.72** | 0.06 | 1.73** | 0.05 |

| JWB-Self | 0.16** | 0.04 | 0.12** | 0.05 | 0.14** | 0.03 | 0.13** | 0.03 |

| JWB-Other | −0.03 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.05 | −0.07** | 0.03 | −0.05 | 0.03 |

| Age | 0.03* | 0.02 | 0.03* | 0.02 | 0.06** | 0.01 | 0.06** | 0.01 |

| Education | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | −0.04** | 0.01 | −0.04** | 0.01 |

| Female | −0.20** | 0.05 | −0.20** | 0.05 | 0.30** | 0.04 | 0.30** | 0.04 |

| Coronavirus experience | 0.11* | 0.04 | 0.11* | 0.04 | 0.10** | 0.03 | 0.10** | 0.03 |

| Power distance | — | — | −0.02 | 0.07 | — | — | 0.00 | 0.04 |

| Individualism | — | — | −0.10 | 0.06 | — | — | −0.07* | 0.03 |

| Masculinity | — | — | 0.04 | 0.06 | — | — | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| Uncertainty avoidance | — | — | −0.11* | 0.04 | — | — | −0.06* | 0.02 |

| Long-term orientation | — | — | −0.08 | 0.06 | — | — | −0.10** | 0.03 |

| Indulgence | — | — | −0.01 | 0.07 | — | — | −0.03 | 0.04 |

| JWB-Self × power distance | — | — | 0.02 | 0.04 | — | — | 0.02 | 0.03 |

| JWB-Other × power distance | — | — | 0.04 | 0.04 | — | — | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| JWB-Self × individualism | — | — | 0.06* | 0.03 | — | — | 0.04 | 0.02 |

| JWB-Other × individualism | — | — | −0.00 | 0.03 | — | — | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| JWB-Self × masculinity | — | — | −0.04 | 0.03 | — | — | −0.02 | 0.02 |

| JWB-Other × masculinity | — | — | 0.04 | 0.03 | — | — | −0.01 | 0.02 |

| JWB-Self × uncertainty avoid | — | — | −0.03 | 0.02 | — | — | −0.03 | 0.02 |

| JWB-Other × uncertainty avoid | — | — | 0.01 | 0.02 | — | — | −0.00 | 0.02 |

| JWB-Self × long orient | — | — | 0.01 | 0.03 | — | — | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| JWB-Other × long orient | — | — | 0.07* | 0.03 | — | — | 0.05* | 0.02 |

| JWB-Self × indulgence | — | — | −0.01 | 0.04 | — | — | −0.03 | 0.03 |

| JWB-Other × indulgence | — | — | 0.05 | 0.04 | — | — | 0.04 | 0.03 |

| Random effects (SD) | ||||||||

| Intercept | 0.65 | 0.53 | 0.32 | 0.20 | ||||

| JWB-Self | 0.11 | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.01 | ||||

| JWB-Other | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.00 | ||||

| Residual | 1.93 | 1.93 | 1.40 | 1.40 | ||||

JWB just world beliefs. Bolded predictors = country-level constructs. Mandatory vaccination likelihood ratio test, country level versus baseline: χ 2(18) = 35.510, p < .01. Mandatory quarantine likelihood ratio test, country level versus baseline: χ 2(18) = 51.518, p < .001.

*p < .05.

**p < .01.

Fig 1.

Cross-level interactions of justice beliefs and national values predicting support for mandatory vaccination (a) and quarantine (b and c). (a) Simple slopes for relation between JWB-Self and vaccine support plotted at low (−1), mean (0), and high (1) levels of country-level individualism. (b) Simple slopes for relation between JWB-Other and vaccine support plotted at low (−3), mean (0), and high (3) levels of country-level long-term orientation. (c) Simple slopes for relation between JWB-Other and quarantine support plotted at low (−1), mean (0), and high (1) levels of country-level long-term orientation. JWB just world beliefs. *p < .05, ** p < .01, ††p = .10.

The intraclass correlation coefficient for quarantine support indicated that 5% of the variance was due to between-country differences. As with vaccination support, adding country-level main effects and cross-level interactions significantly improved model fit, χ 2(18) = 51.518, p < .001. Once again, there were significant main effects of JWB-Self (b = 0.129, p < .01) and uncertainty avoidance (b = −.055, p = .01). Additionally, there were main effects of individualism (b = −0.065, p = .02), and long-term orientation (b = −0.103, p < .001). Finally, there was a significant cross-level interaction between JWB-Other and long-term orientation (b = 0.049, p = .01). As seen in Fig. 1c, JWB-Other was associated with less support for mandatory quarantine in countries lower in long-term orientation but was positively associated in countries higher in long-term orientation.

DISCUSSION

This study suggests that endorsing vaccination and quarantine behavioral mandates to contain SARS-CoV-2 transmission are simultaneously predicted by individual-level justice beliefs and higher-order national values. At the individual level, JWB-Self was positively associated with support for policies advocating for stringent vaccination and quarantine, whereas JWB-Other was not associated with either mandate. These findings highlight the possibly that endorsing SARS-CoV-2 containment measures may better reflect a health-related social attitude that is connected to beliefs about the fairness of one’s own world than the world more broadly.

We also found that cultural values were associated with support for vaccination and quarantine prevention policies. Specifically, and somewhat counterintuitive, support for mandatory vaccination and quarantine were both negatively associated with long-term orientation. According to Hofstede, countries high in long-term orientation are focused on future. In turn, they more strongly value adaptability and innovation to address social struggles, whereas countries low in long-term orientation rely on norms and rules to navigate immediate problems, and are risk averse [11]. Citizens of long-term orientation cultures that favor adaptability may prefer public health solutions to be more innovative than policy mandates, whereas cultures that favor rule adherence and risk aversion may support mandates that can immediately enact proven-effective behavioral change [6]. Similar to prior research, we also found that quarantine support was negatively associated with individualism and uncertainty avoidance [5, 16]. Members of individualistic societies may be less likely to endure behaviors mandates that threaten a sense of personal freedom, such as quarantining [14]. In tandem, people tend to more naturally avoid social gatherings in countries high in uncertainty avoidance, suggesting that mandatory policies may be viewed as unnecessary [5]. Whereas some research suggests power distance, masculinity and indulgence may be linked to COVID-19-related public health measures [6, 16, 17], these dimensions were not presently associated with support for vaccination and quarantine mandates.

Perhaps most importantly, and with an eye toward translational impacts of the present findings, we observed two cross-level interactions between justice beliefs and national values, illuminating effects of believing in justice on support for COVID-19 behavioral mandates could depend on national context. Specifically, we found that JWB-Self was more strongly associated with support for vaccination and quarantine policies in highly individualistic countries (i.e., less strongly linked in collectivist countries). Individualism could enhance the positive association between JWB-Self and COVID-19 mandates to the extent that self-concern is psychologically congruent with individualism, but not collectivism. For example, individualism places value on attaining personal goals [11] which is also enabled by believing the word is personally fair [8].

We also found that JWB-Other was associated with less support for mandatory vaccination in countries low in long-term orientation, but more support in countries high in long-term orientation. A JWB-Other × long-term orientation interaction for mandatory quarantine mirrored this pattern to the extent that long-term orientation attenuated the negative association between JWB-Other and quarantine support, although JWB-Other was unrelated with quarantine support in countries high in long-term orientation, as opposed to positively associated. Seeing the world as fair to others may carry sentiments that people should do what is necessary to ensure their own health and well-being, as opposed to relying on social policies for safety. Countries low in long-term orientation, which are risk averse and more heavily rely on social norms to navigate uncertainty, may provide a context that accentuates this effect, to the extent that existing norms may also direct individuals to take care of themselves. In contrast, countries high in long-term orientation are adaptable and future oriented. Notable as well is that the most long-term oriented countries include many Southeast Asian nations, where JWB-Others tends to be more strongly endorsed and predicts coping and resilience, in addition to JWB-Self. A future-oriented perspective has likewise been shown to accentuate resilience effects of JWB-Other in these cultures [21].

With an eye toward potential applications, the present study provides two crucial insights. First, activating personal justice beliefs through health communication could be a broadly useful intervention lever, given the robust and cross-culturally consistent positive association between personal justice beliefs and support for quarantine and vaccination. On the basis that JWB-Self promotes a sense of control, public health messaging could highlight the restored sense of personal control afforded by vaccination and quarantine. This potential intervention is supported by justice research that has demonstrated the relative ease with which personal justice beliefs can be briefly and momentarily activated in individuals [22]. Second, findings related to cultural values suggest that tailoring rather than broad application of health communication strategies may be needed [23]. For example, activating personal justice beliefs through public health communication could be most effective when deployed in highly individualistic countries. Alternatively, countries high in long-term orientation may benefit from communications that additionally or instead include elements of justice for others, perhaps including communications that encompass the potential for all to benefit in the future through supporting present public health mandates. Another potential tailoring approach could involve activation of cultural mindsets to match individual-level justice beliefs. For example, individuals with especially robust personal justice beliefs could be directed to messaging that enables an individualistic mindset when considering policy mandates. However, matching cultural mindsets to justice beliefs would require a priori identifying individual-level justice endorsements, and thus may be less practical than tailoring justice-oriented communications to cultural contexts.

Several limitations suggest cautious interpretation and future directions. First, this research relied on the use of convenience samples and was cross-sectional. Related, our within-country samples sizes were small for many countries, and were nonrepresentative of countries in total. These aspects preclude both generalizability and causal inference. Second, although variables were linked to policy support, we did not measure quarantine or vaccination behavior. Moreover, we controlled for one’s own social network infection but not country prevalence rates, and we did not probe within-country differences, both of which may be revelatory. Future research could also consider alternatives to Hofstede’s cultural values structure, as well as other important policy measures, such as support for social distancing and mask-wearing policy mandates. Limitations notwithstanding, our findings may contribute to effective prevention of SARS-CoV-2 transmission by revealing individual and national characteristics jointly influence endorsement of prevention policies. Justice beliefs may be a particularly potent individual-level influence, and the belief in personal justice may be widely associated with support for prevention-oriented behavioral mandates. Moreover, justice beliefs may impact support for SARS-CoV-2 prevention policies differently across nations, and according to interactions with diverse national values. Policy makers and public health practitioners may begin to better understand the effects of behavioral mandates policies by simultaneously considering individual-level and national-level influences, especially to the extent that these facets may operate simultaneously and synergistically to affect COVID-19 policy support and adherence.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Todd Lucas, Division of Public Health, College of Human Medicine, Michigan State University, Flint, MI, USA; Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, College of Human Medicine, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, USA.

Mark Manning, Department of Psychology, Oakland University, Rochester, MI, USA.

Peter Strelan, School of Psychology, University of Adelaide, Adelaide, SA, Australia.

Catalina Kopetz, Department of Psychology, Wayne State University, Detroit, MI, USA.

Maximilian Agostini, Department of Psychology, University of Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands.

Jocelyn J Bélanger, Department of Psychology, New York University—Abu Dhabi, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates.

Ben Gützkow, Department of Psychology, University of Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands.

Jannis Kreienkamp, Department of Psychology, University of Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands.

N Pontus Leander, Department of Psychology, University of Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands.

Funding

This study was funded by the following sources: New York University Abu Dhabi (VCDSF/75-71015), the University of Groningen (Sustainable Society & Ubbo Emmius Fund), and the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (COV20/00086).

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest: All authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval: All procedures performed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Transparency Statements: Deidentified data from this study are available in a protected archive at PsyCorona.org. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors. This study and its hypotheses were prereviewed at PsyCorona.org, but was not formally preregistered. The analysis plan was not formally registered. Analytic code used to conduct the analyses presented in this study may be available by emailing the corresponding author. All materials used to conduct the study are available in a protected archive at PsyCorona.org.

References

- 1. Cohen MS, Corey L.. Combination Prevention for COVID-19. Science 2020;368:551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mullard A. How COVID vaccines are being divvied up around the world. Nature. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nussbaumer-Streit B, Mayr V, Dobrescu AI, et al. Quarantine alone or in combination with other public health measures to control COVID-19: a rapid review. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;82(6):501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lazarus JV, Ratzan SC, Palayew A, et al. A global survey of potential acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine. Nat Med. 2021;27(2):225–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Huynh TLD. Does culture matter social distancing under the COVID-19 pandemic? Saf Sci. 2020;130:104872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wang Y. Government policies, national culture and social distancing during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic: international evidence. Saf Sci. 2021;135:105138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lerner MJ. The belief in a just world. In: The Belief in a Just World. Boston, MA: Springer; 1980:9–30. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bartholomaeus J, Strelan P. The adaptive, approach-oriented correlates of belief in a just world for the self: a review of the research. Pers Individ Dif. 2019;151:109485. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hafer CL, Sutton R. Belief in a just world. In: Handbook of Social Justice Theory and Research. New York, NY: Springer; 2016:145–160. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lucas T. Health consequences and correlates of social justice. In: Sweeny K, Robbins ML, eds. The Wiley Encyclopedia of Health Psychology. 2020:223–230. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hofstede G.Empirical models of cultural differences. In Bleichrodt N, Drenth PJD, eds. Contemporary issues in cross-cultural psychology. Swets & Zeitlinger Publishers; 1991:4–20. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Messner W. The institutional and cultural context of cross-national variation in COVID-19 outbreaks, medRxiv, 2020. doi: 10.1101/2020.03.30.20047589 [DOI]

- 13. Wolf LJ, Haddock G, Manstead A. S., and Maio G. The importance of (shared) human values for containing the COVID-19 pandemic. Br J Soc Psychol. 2020:59(3):618–627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Borisova LV, Martinussen PE, Rydland HT, Stornes P, Eikemo TA. Public evaluation of health services across 21 European countries: the role of culture. Scand J Public Health. 2017;45(2):132–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Deschepper R, Grigoryan L, Lundborg CS, et al. Are cultural dimensions relevant for explaining cross-national differences in antibiotic use in Europe? BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8(1):123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gokmen Y, Baskici C, Ercil Y. The impact of national culture on the increase of COVID-19: a cross-country analysis of European countries. Int J Intercult Relat. 2021;81:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Windsor LC, Yannitell Reinhardt G, Windsor AJ, et al. Gender in the time of COVID-19: evaluating national leadership and COVID-19 fatalities. PLoS One. 2020;15(12):e0244531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lucas T, Zhdanova L, Wendorf CA. Procedural and distributive justice beliefs for self and others: multilevel associations with life satisfaction and self-rated health. J Happiness Stud. 2013;14(4):1325–1341. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lucas T, Kamble SV, Wu MS, Zhdanova L, Wendorf CA. Distributive and procedural justice for self and others: measurement invariance and links to life satisfaction in four cultures. J Cross Cult Psychol. 2016;47(2):234–248. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Preacher KJ, Curran PJ, Bauer DJ. Computational tools for probing interactions in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. J Educ Behav Stat. 2006;31(4):437–448. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lucas T, Drolet CE, Strelan P, Karremans JC, Sutton RM. Time frame and justice motive: future perspective moderates the adaptive function of general belief in a just world. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):e80668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lucas T, et al. Fairness and forgiveness: effects of priming justice depend on justice beliefs. Curr Psychol. 2020:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hawkins RP, Kreuter M, Resnicow K, Fishbein M, Dijkstra A. Understanding tailoring in communicating about health. Health Educ Res. 2008;23(3):454–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.