Abstract

Background

Prisons and jails are high-risk settings for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Vaccines may substantially reduce these risks, but evidence is needed on COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness for incarcerated people, who are confined in large, risky congregate settings.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study to estimate effectiveness of messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccines, BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech) and mRNA-1273 (Moderna), against confirmed severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infections among incarcerated people in California prisons from 22 December 2020 through 1 March 2021. The California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation provided daily data for all prison residents including demographic, clinical, and carceral characteristics, as well as COVID-19 testing, vaccination, and outcomes. We estimated vaccine effectiveness using multivariable Cox models with time-varying covariates, adjusted for resident characteristics and infection rates across prisons.

Results

Among 60 707 cohort members, 49% received at least 1 BNT162b2 or mRNA-1273 dose during the study period. Estimated vaccine effectiveness was 74% (95% confidence interval [CI], 64%–82%) from day 14 after first dose until receipt of second dose and 97% (95% CI, 88%–99%) from day 14 after second dose. Effectiveness was similar among the subset of residents who were medically vulnerable: 74% (95% CI, 62%–82%) and 92% (95% CI, 74%–98%) from 14 days after first and second doses, respectively.

Conclusions

Consistent with results from randomized trials and observational studies in other populations, mRNA vaccines were highly effective in preventing SARS-CoV-2 infections among incarcerated people. Prioritizing incarcerated people for vaccination, redoubling efforts to boost vaccination, and continuing other ongoing mitigation practices are essential in preventing COVID-19 in this disproportionately affected population.

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, vaccine, vaccination, effectiveness

This study provides evidence of effectiveness of mRNA vaccines in preventing severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infections in incarcerated populations, including among medically vulnerable residents. Estimates in this large congregate population were consistent with results from randomized trials and observational studies in other populations.

The BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech) and mRNA-1273 (Moderna) vaccines appear highly effective in preventing severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection and coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Augmenting efficacy evidence from clinical trials [1, 2], observational studies among healthcare workers [3, 4], adults aged ≥65 years [5], and the general community [6, 7] have reported levels of protection from full vaccination ranging from 89% to 95%. Relatively few studies have examined effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines in congregate settings, where risks of transmission are very high [8, 9].

Prisons and jails are especially risky congregate settings. Living quarters are often densely populated and poorly ventilated, physical distancing is typically infeasible, and preexisting medical conditions associated with severe COVID-19 are prevalent among incarcerated people [10, 11]. Recognizing these risks and the considerable potential for vaccines to reduce them, approximately half of US states have prioritized incarcerated people for COVID-19 vaccines. In sharp contrast, 15 states have not included incarcerated people in vaccine distribution plans or have assigned them to lowest-priority tiers [12, 13].

The California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR), which operates the second-largest state prison system, launched a COVID-19 vaccination program on 22 December 2020, and rapidly scaled up the program across its 35 prisons [14]. CDCR has collected detailed data relevant to COVID-19 risks, interventions, and outcomes, and has maintained an extensive, multilayered testing program since early in the pandemic when large outbreaks occurred [15, 16]. We analyzed these data to estimate effectiveness of mRNA vaccines against confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection among nearly 61 000 incarcerated people in California.

METHODS

Study Design and Population

We conducted a retrospective cohort study spanning the 70-day period from 22 December 2020 through 1 March 2021, during which residents were offered either BNT162b2 or mRNA-1273 vaccines. Prioritization criteria that CDCR used to direct first-dose offers changed over time as supply expanded and state and federal guidance evolved. Criteria included residency in a specialized medical or psychiatric care setting, age and medical comorbidities, no confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection (or none in the previous 90 days), and participation in penal labor. CDCR prioritized timely second-dose offers to adhere to recommended dosing schedules.

Residents were eligible for inclusion in the study cohort if they were incarcerated in a CDCR prison on the study start date and had no prior confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection. Cohort members contributed observation time beginning on the study start date and ending on the day of the earliest of the following events: release from CDCR custody, sample collection for a positive SARS-CoV-2 diagnostic test, or study end date.

Data and Key Measures

CDCR collects and stores daily data on each resident. Detailed SARS-CoV-2 testing information came from a multilayered resident testing program that included risk-based routine testing, surveillance testing, and testing in response to detected outbreaks (Supplementary Table 1). Information provided on accepted vaccine doses allowed us to classify cohort members’ daily vaccination status into 6 categories: unvaccinated, from 0 to 6 days after receiving a first dose, from 7 to 13 days after a first dose, from 14 days after a first dose until receipt of a second dose, from 0 to 13 days after a second dose, and from 14 days after a second dose.

In addition to details on testing and vaccination, data provided for this study included demographic characteristics (sex, age, racial or ethnic group), documented history of 25 comorbid conditions (eg, hypertension, chronic kidney disease, asthma), and a composite COVID-19 risk score from CDCR’s electronic health record system. CDCR designed the risk score to grade risks of severe illness from SARS-CoV-2 infections (Supplementary Table 2), and the agency has used this score to guide COVID-19 mitigation policies, including prioritization of testing and vaccination. We also obtained person-day–level variables indicating each resident’s prison, facility, building, housing unit, floor, and room of residence; room type (cell or dormitory); security level; and participation in penal labor.

To obtain a measure of risk of infection from correctional staff, we constructed a prison-day–level variable comprising the rolling 7-day COVID-19 case rate among staff at each prison. Infections among correctional staff were identified through regular SARS-CoV-2 testing, mandated and administered by CDCR (Supplementary Table 1).

Statistical Analysis

We fit person-day–level data using the Andersen-Gill extension of the Cox proportional hazards model [17] to account for time-varying covariates. The primary outcome of interest was SARS-CoV-2 infection, confirmed by positive polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or antigen test (>93% were PCR). We specified exposure status according to the 6 vaccination categories described above. Effectiveness estimates are expressed as 1 minus the hazard ratio.

Analyses adjusted for residents’ racial or ethnic group, COVID-19 risk score, security level, room type, participation in penal labor, staff case rate, and prison (fixed effects). We did not adjust for sex because men and women are generally housed in separate prisons, making this variable highly collinear with prison. To account for nonindependence between cohort members, we clustered standard errors by housing unit. Housing units are discrete cohorts within prisons, consisting of residents who co-participate in activities (eg, recreation, laundry, dining).

All analyses were performed using R software, version 3.5.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing). Additional details regarding model and variable specifications are provided in the Supplementary Appendix.

Secondary Analyses

We conducted 4 sets of secondary analyses. First, we estimated effectiveness in 2 subgroups of interest. Specifically, recognizing that our primary analysis mixes effects of 2 different vaccines, we ran 1 subgroup analysis focusing on mRNA-1273 vaccinations only (which accounted for 78% of all first doses and 72% of all doses administered in the study period). We also estimated effectiveness among medically vulnerable residents by restricting the analytic cohort to residents with COVID-19 risk scores of 2 or higher, indicating moderate or high risk. Residents with COVID-19 risk scores of 2 or higher were either aged ≥65 years or <65 years with comorbid conditions associated with severe COVID-19 disease (Supplementary Table 2).

Second, we estimated effectiveness in a broader population that included residents with prior infections and those who entered prison during the study period. Third, we examined the sensitivity of our effectiveness estimates to alternative model specifications, including censoring observation time at the collection date of cohort members’ last test (to exclude time periods in which infection status was unknown) and computing cluster-robust variance estimators with clusters defined at various levels (prison, facility, building, floor, room, and person). Finally, to assess the sensitivity of estimates to choice of study period, we reestimated effectiveness using a series of alternative study end dates between 15 February and 1 July 2021.

Study Oversight

The study was approved by the institutional review board at Stanford University (protocol number 55835). It was reviewed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and conducted according to applicable federal law and CDC policy (see, eg, 45 Code of Federal Regulations [C.F.R.] part 46, 21 C.F.R. part 56; 42 United States Code [U.S.C.] §241[d]; 5 U.S.C. §552a; 44 U.S.C. §3501 et seq). Results are reported in accordance with Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines (checklist in Supplementary Appendix) [18].

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics and Vaccination Uptake

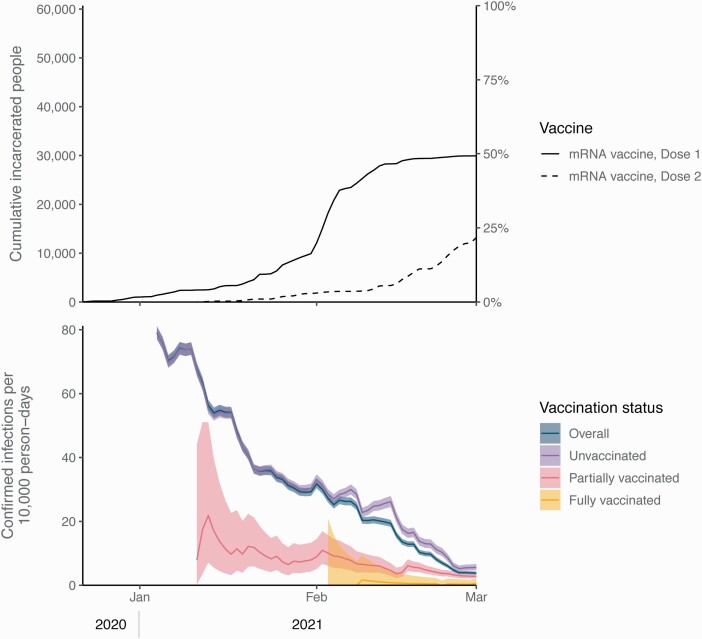

A total of 60 707 residents met the cohort inclusion criteria (Supplementary Figure 1 and Supplementary Table 3) and were followed for an average of 57.6 days (median, 70 days). By 1 February 2021, 20% of them received at least 1 mRNA dose and 3% received 2 doses; by 1 March, 49% received at least 1 dose and 22% received 2 doses (Figure 1 and Supplementary Figure 2). The mean interval between doses was 20.8 days (standard deviation [SD], 2.7 days) for those who received 2 BNT162b2 doses and 28.0 days (SD, 3.5 days) for those who received 2 mRNA-1273 doses.

Figure 1.

Cumulative vaccinations with 1 or 2 doses of messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccines (top panel) and 14-day rolling rates of confirmed infections per 10 000 person-days by vaccination status (bottom panel), among study cohort of incarcerated people in California state prisons without confirmed infections prior to 22 December 2020. Time periods with <200 people tested were excluded. Shaded areas represent 95% confidence intervals. Partially vaccinated status defined as ≥14 days after a first dose until receipt of a second dose; fully vaccinated status defined as ≥14 days after a second dose.

Most cohort members had risk factors for severe outcomes from COVID-19 infection: 84% had at least 1 medical condition defined by CDC as a marker of severe COVID-19–related illness [19], and 31% had moderate or high COVID-19 risk according to CDCR’s scoring algorithm (Table 1). Cohort members who had received 1 or more vaccine doses by the end of the study period tended to be older than those who had not, and were more likely to have medical conditions and higher COVID-19 risk scores and be non-Hispanic white or Hispanic/Latino (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 3).

Table 1.

Demographic, Health, and Carceral Characteristics of the Study Cohort of Incarcerated People in California State Prisons

| Characteristic | All Cohort Members (n = 60 707) | Vaccinated Cohort Members (n = 29 947) |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | ||

| Age category, y | ||

| 18–39 | 29 922 (49.3) | 12 378 (41.3) |

| 40–59 | 23 469 (38.7) | 12 888 (43.0) |

| ≥60 | 7316 (12.1) | 4681 (15.6) |

| Race or ethnicitya | ||

| Hispanic or Latino | 25 914 (42.7) | 13 459 (44.9) |

| Black or African American | 19 894 (32.8) | 8166 (27.3) |

| White | 10 957 (18.0) | 6247 (20.9) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 670 (1.1) | 325 (1.1) |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 833 (1.4) | 422 (1.4) |

| Other | 2439 (4.0) | 1328 (4.4) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 58 017 (95.6) | 28 636 (95.6) |

| Female | 2661 (4.4) | 1311 (4.4) |

| Clinical characteristics | ||

| COVID-19 risk score categoryb | ||

| Low (0–1) | 42 093 (69.3) | 18 829 (62.9) |

| Moderate (2–3) | 11 509 (19.0) | 6415 (21.4) |

| High (≥4) | 7105 (11.7) | 4703 (15.7) |

| Medical conditions | ||

| Any preexisting conditionc | 51 129 (84.2) | 25 881 (86.4) |

| Any immunocompromising conditiond | 2031 (3.3) | 1349 (4.5) |

| Advanced liver disease | 2141 (3.5) | 1454 (4.9) |

| Asthma | 8307 (13.7) | 4049 (13.5) |

| Cancer | 1773 (2.9) | 1159 (3.9) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 8889 (14.6) | 5406 (18.1) |

| COPD | 1757 (2.9) | 1207 (4.0) |

| Connective tissue disorder | 481 (0.8) | 314 (1.0) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 3115 (5.1) | 1943 (6.5) |

| Diabetes | 4886 (8.0) | 3090 (10.3) |

| HIV | 481 (0.8) | 309 (1.0) |

| Hypertension | 15 068 (24.8) | 8786 (29.3) |

| Immunocompromised | 844 (1.4) | 564 (1.9) |

| Overweighte | 21 137 (34.8) | 10 173 (34.0) |

| Obesitye | 21 960 (36.2) | 11 386 (38.0) |

| Severe obesity | 2553 (4.2) | 1414 (4.7) |

| Disability | ||

| Any disabilityf | 23 422 (38.6) | 12 892 (43.0) |

| Cognitive | 993 (1.6) | 664 (2.2) |

| Hearing | 2033 (3.3) | 1319 (4.4) |

| Mental health | 19 467 (32.1) | 10 510 (35.1) |

| Mobility | 6980 (11.5) | 4453 (14.9) |

| Speech | 96 (0.2) | 71 (0.2) |

| Vision | 495 (0.8) | 323 (1.1) |

| Carceral characteristics | ||

| Room type | ||

| Cell | 45 304 (74.6) | 22 954 (76.6) |

| Dorm | 15 403 (25.4) | 6993 (23.4) |

| Security level | ||

| 1 (minimum) | 4953 (8.2) | 2041 (6.8) |

| 2 | 24 729 (40.7) | 13 247 (44.2) |

| 3 | 10 763 (17.7) | 4884 (16.3) |

| 4 (maximum) | 20 262 (33.4) | 9775 (32.6) |

| Participation in penal labor | 15 153 (25.0) | 7478 (25.0) |

Data are presented as No. (%). Persons within the study cohort were incarcerated on 22 December 2020 and did not have prior confirmed severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection (confirmed by positive polymerase chain reaction or antigen tests) documented in California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) clinical records. Vaccinated residents were vaccinated between 22 December 2020 and 1 March 2021.

Abbreviations: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

All categories other than “Hispanic or Latino” refer to non-Hispanic ethnicity.

Based on CDCR risk score. See Supplementary Table 2.

Refers to the set of conditions identified by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as risk factors for increased risk of severe COVID-19 among adults of any age, specifically: advanced liver disease, asthma, cancer, chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cardiovascular disease, dementia, Parkinson’s, diabetes, on dialysis, hemoglobinopathy disorders, HIV, hypertension, immunocompromised, lung disease, neurologic disorders, pregnancy, vasculitis, overweight, obesity, and severe obesity.

Refers to diagnosis of immunocompromised, severe HIV, or severe cancer.

Overweight refers to body mass index (BMI) 25–29.9 kg/m2; obesity refers to BMI 30–39.9 kg/m2; severe obesity refers to BMI ≥40 kg/m2.

Refers to presence of disability in 6 categories: cognitive, hearing, mental health, mobility, speech, and vision.

Testing Rates by Vaccination Category

Cohort members had a median of 6 COVID-19 tests during the study period (interquartile range, 2–10). Testing rates were lower in the unvaccinated group (Supplementary Figure 3). Over the study period, testing decreased across all groups.

Confirmed Infections and Other COVID-19 Outcomes

A total of 13 216 confirmed infections (37.8 per 10 000 person-days), 393 hospitalizations (1.1 per 10 000 person-days), and 48 deaths (0.1 per 10 000 person-days) were documented among cohort members. Most of these outcomes occurred among unvaccinated people (Table 2 and Supplementary Table 4). Incidence of infection decreased during the study period, from 40.2 per 10 000 person-days in January 2021 to 11.8 in February (Figure 1). Additional details on testing and confirmed infections, including time series by specific prison, are shown in Supplementary Figures 3–5.

Table 2.

Persons, Person-Days, and Vaccine Effectiveness Against Coronavirus Disease 2019 Infection Among Study Cohort of Incarcerated People in California State Prisons, by Vaccination Status, 22 December 2020 to 1 March 2021

| COVID-19 Vaccination Status | Confirmed Infectiona | Hospitalizedb | Diedc | Tested | Total | Median Follow-up, d | Person-Days | Positive per 10 000 Person-Days | Effectiveness, %, Unadjustedd | Effectiveness, %, Adjustedd |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unvaccinated | 12 318 | 356 | 44 | 53 415 | 60 673 | 43 | 2 633 734 | 46.8 | (Ref) | (Ref) |

| Vaccinated with 1 dose | ||||||||||

| 0–6 days after first dose | 527 | 20 | 3 | 19 767 | 29 947 | 7 | 206 960 | 25.5 | –4 (–44 to 25) | 16 (–15 to 39) |

| 7–13 days after first dose | 237 | 11 | 1 | 17 200 | 28 902 | 7 | 199 746 | 11.9 | 26 (–8 to 50) | 44 (20–61) |

| ≥14 days after first dose until second dose | 101 | 4 | 0 | 16 436 | 27 392 | 11 | 286 856 | 3.5 | 63 (48–74) | 74 (64–82) |

| Vaccinated with 2 doses | ||||||||||

| 0–13 days after second dose | 30 | 2 | 0 | 7152 | 13 183 | 11 | 120 141 | 2.5 | 74 (41–89) | 85 (66–94) |

| ≥14 days after second dose | 3 | 0 | 0 | 2381 | 3659 | 14 | 50 033 | 0.6 | 93 (76–98) | 97 (88–99) |

Abbreviations: COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; SARS-CoV-2; severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

Confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection is defined as having a positive polymerase chain reaction or antigen diagnostic test for SARS-CoV-2.

Hospitalization related to a SARS-CoV-2 infection is defined as a hospitalization that occurred within 3 days prior to or 14 days after an infection was initially confirmed. For attribution to person-days stratified by vaccination category, hospitalizations were assigned to the collection date for a confirmed infection.

All deaths related to a SARS-CoV-2 infection were classified and confirmed by the California Correctional Health Care Services. For attribution to person-days stratified by vaccination category, deaths were assigned to the collection date for a confirmed infection.

Unadjusted effectiveness estimates based on Cox proportional hazards model with only vaccination status indicators as explanatory variables. Adjusted effectiveness estimates based on Cox proportional hazards model including controls for residents’ race or ethnic group (Hispanic, non-Hispanic Black or African American, non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaska Native, non-Hispanic Asian or Pacific Islander, non-Hispanic other), COVID-19 risk score (0 to ≥4, top-coded), security level (1, 2, 3, 4), room type (cell, dorm), involvement in penal labor (yes, no), the prison-specific 7-day rolling COVID-19 case rate for staff (continuous), and prison (fixed-effect).

Vaccine Effectiveness

There was no significant difference in the adjusted hazard ratio for confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection during days 0–6 after receiving a first dose relative to unvaccinated status (Table 2). From 7 to 13 days after a first dose, estimated vaccine effectiveness was 44% (95% confidence interval [CI], 20%–61%), and from 14 days after a first dose until receipt of a second dose, effectiveness was 74% (95% CI, 64%–82%). Effectiveness estimates were 85% (95% CI, 66%–94%) from 0 to 13 days after a second dose and 97% (95% CI, 88%–99%) from 14 days after a second dose.

Secondary Analyses

Subgroup analyses produced similar estimates of effectiveness to the full cohort analysis (Supplementary Table 5A). Among those receiving the mRNA-1273 vaccine, estimated effectiveness was 71% (95% CI, 58%–80%) from 14 days after first dose until receipt of second dose and 96% (95% CI, 67%–99%) from 14 days after second dose. Among cohort members at moderate or high risk for severe COVID-19, effectiveness estimates were 74% (95% CI, 62%–82%) from 14 days after first dose until receipt of second dose and 92% (95% CI, 74%–98%) from 14 days after second dose.

Estimates in an expanded cohort that included new entrants and residents with prior infections did not differ appreciably from the main cohort analysis (Supplementary Table 5B). Results were also insensitive to model specification choices, including censoring of observation time at the date of cohort members’ last test and clustering standard errors at different residential levels (Supplementary Table 5C and 5D).

In secondary analyses that modified the study end date, effectiveness estimates for fully vaccinated residents (ie, from 14 days after second dose) decreased from 98% (95% CI, 82%–100%) to 82% (95% CI, 69%–89%) over a series of end dates between 15 February and 1 July 2021 (Supplementary Table 5E). Study months spanning March to July were characterized by significantly lower outbreak risks across all facilities (0.4 confirmed infections per 10 000 person-days); lower testing (474 tests per 10 000 person-days); and high overall vaccination coverage rates (72% and 75% of cohort members who were still in custody had received at least 1 dose or had tested positive by 1 April and 1 July, respectively).

DISCUSSION

This study found that BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273 vaccines were highly effective against confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection among members of a high-risk and racially diverse population of incarcerated people. Beginning 14 days after a second mRNA vaccine dose, estimated effectiveness in this population was 97%. The vaccines were also highly effective among prison residents at higher risk for severe COVID-19.

Our estimated effectiveness among fully vaccinated people in California prisons was higher than previous estimates in a skilled nursing facility (66% among residents and 76% among staff from 14 days after a second BNT162b2 dose) [9]. It was more similar to estimates reported from healthcare and other frontline workers [3, 4] and population-level studies in Israel [6, 7], which all reported estimates above 90%. Estimates of effectiveness of partial vaccination have been more variable, and our estimate of 74% fell within the range observed across other studies (46%–81%) [3, 4, 7, 8].

To our knowledge, this is the first multisite study to assess effectiveness of a COVID-19 vaccination program in carceral settings. It has several strengths. We used detailed daily information on vaccination status and key COVID-19 outcomes for each resident. These data allowed us to adjust for key potential confounders, including risk factors for severe COVID-19, housing arrangements, and participation in penal labor. An extensive testing program in this population facilitated relatively complete measurement of SARS-CoV-2 infections. In addition, the large sample size permitted estimates of effectiveness within particular subgroups of interest (eg, medically vulnerable).

Understanding vaccine effectiveness among people at high risk for severe disease is a priority. Our estimated effectiveness for partial and full vaccination did not differ appreciably between the full cohort and subsets characterized by moderate or high risk for severe COVID-19. This bolsters growing evidence that mRNA vaccines provide substantial protection in older adults [5, 7], people with preexisting conditions [7, 20], and residents of skilled nursing facilities [8, 9]. Our results also extend evidence from studies of healthcare workers indicating these vaccines are effective in environments characterized by high transmission risks.

In observational cohort studies like ours, potential for bias due to confounding is an important consideration. Vaccines were not offered randomly to residents—in particular, those with risk factors for severe disease were prioritized. Given the latency of biologically plausible protection, the days after vaccination can serve as an indicator of bias, with large effectiveness estimates signaling substantial residual confounding [21]. We included an exposure category for the first week after a first mRNA vaccine dose to assess the presence of such residual confounding, and detected a statistically insignificant 16% effectiveness for this negative control exposure. Vasileiou et al [20] reported a much higher estimate, 86% protection against COVID-19 hospitalizations during the first week after vaccination for BNT162b2, in a previous study on effectiveness in Scotland.

Residents were tested frequently (median 6 tests) during the 70-day study period, but testing was neither routine, random, nor compulsory, creating potential for ascertainment bias. Several results provide some reassurance in this regard. First, vaccinated cohort members overall had 25% higher testing rates than unvaccinated members. Thus, the most plausible bias from differential testing would be more complete case detection among the vaccinated, which would lead to underestimating vaccine effectiveness. Second, an analysis that censored follow-up on the last test collection date for a cohort member produced effectiveness estimates similar to those from the main analysis.

Extending the study period through 1 July 2021 added 4 months in which testing and case rates were low and a relatively large proportion of prison residents had been vaccinated. We found lower levels of estimated effectiveness for the fully vaccinated group over this extended period—an expected result, and a trend seen in the 6-month vaccine efficacy clinical trial for the BNT162b2 vaccine [22]. Accumulation of undetected infections may have contributed to dilution of estimated effectiveness, especially among residents at lower risk for severe COVID-19, who were tested less frequently and vaccinated later. Additional contributors may have included increasing bias in the composition of the unvaccinated group toward residents who declined vaccination, as well as cohort selection induced by heterogeneity in infection risk [23]. For instance, if the vaccine offered partial (or “leaky”) protection [24], high infection risk within an unvaccinated group that is initially highly susceptible could induce selection bias over time as the most susceptible people are removed from the group, which would decrease estimated effectiveness of vaccination.

The study has several other limitations. First, our estimates of effectiveness focused on confirmed infections, not other important outcomes such as symptomatic infections or severe disease. Incidence of hospitalizations and deaths in our cohort during the study period was too low to support rigorous analysis of those outcomes, and symptom reporting was unreliable during the study period [25]. A related point is that we were only able to estimate effectiveness with reference to the date of test sample collection, not transmission date, which allows for the possibility that some detected infections might have preceded vaccination. Second, we evaluated effectiveness against any SARS-CoV-2 infection, not specific viral variants, because CDCR conducted limited viral genome sequencing during the study period. As the B.1.617.2 (Delta) variant became dominant and cases rose in the general community over the months of June and July 2021 [26, 27], CDCR detected a total of 286 cases among a population of nearly 99 000 residents during this period [28], a substantially lower rate when compared to the period between mid-March 2020 to mid-February 2021, during which the weekly case count was consistently above 200, peaking at 5659 in December 2020. Lower incidence after February 2021 suggests that there may be substantial protection against outbreaks in this population with high levels of vaccination and prior infections, including during a period marked by increasing prevalence of more highly transmissible variants. However, as people continue to become infected and more outbreaks occur, further follow-up is necessary to reassess the protection afforded by vaccines [29]. Finally, the generalizability of our results to residents of jails, which are shorter-term local correctional facilities for those awaiting trial or sentencing, and other correctional systems is unknown.

Residents of prisons and jails have borne a disproportionately large share of disease burden during the COVID-19 pandemic. Findings from this study—building on a growing evidence base indicating vaccine efficacy and effectiveness across a range of populations and settings—suggest that mRNA vaccines are extremely effective in protecting incarcerated people against infection, including residents at high risk of severe COVID-19. Continued emphasis on vaccination and other ongoing mitigation practices are essential in preventing COVID-19 in this disproportionately affected population. Incarcerated people, correctional workers, and the wider community all stand to benefit from those efforts.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Clinical Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Author contributions. J. A. S., E. T. C., J. R. A., D. M. S., J. D. G.-F., and F. A.-E. contributed to study design. E. T. C., D. L., Y. Z., E. L., and L. P. contributed to data analysis. All authors contributed to data interpretation. E. T. C., J. A. S., and D. M. S. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. J. A. S., E. T. C., J. R. A., D. M. S., J. D. G.-F., F. A.-E., S. J. S., J. R. V., R. E. W., and D. L. reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors approved the final draft.

Acknowledgments. The authors thank Joseph Bick, John Dunlap, Heidi Bauer, and the other staff members at California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation for providing data and assistance with interpretation of study results. They also acknowledge help from members of the Stanford-Center for Research and Teaching in Economics Coronavirus Simulation Model consortium.

Disclaimer. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Financial support. This was supported in part by the COVID-19 Emergency Response Fund at Stanford, established with a gift from the Horowitz Family Foundation; the National Institute on Drug Abuse at the National Institutes of Health (R37-DA15612); the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention through the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists (NU38OT000297-02); the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program (DGE-1656518); and the Open Society Foundations (OR2020-69521).

Potential conflicts of interest. D. L. reports being a full-time employee of the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (providing the data for these analyses was part of the job). D. M. S., E. T. C., J. R. A., J. A. S., J. D. G.-F., L. P., Y. Z., and E. L. are members of the Stanford research team, which has been engaged in conducting COVID-19–related research for the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) since April 2020; CDCR provides the Stanford research team with data to enable this research to be done, but has not provided any funding for the work to date. E. T. C. reports Stanford Graduate Fellowship during the conduct of the study. F. A.-E. reports receiving consulting fees to train Janssen modelers how to build infectious disease models in R using a respiratory syncytial virus infection model as an example. All other authors report no potential conflicts.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

Contributor Information

Elizabeth T Chin, Department of Biomedical Data Science, Stanford University, Stanford, California, USA.

David Leidner, California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, Sacramento, California, USA.

Yifan Zhang, Department of Health Policy, Stanford University, Stanford, California, USA.

Elizabeth Long, Department of Health Policy, Stanford University, Stanford, California, USA.

Lea Prince, Department of Health Policy, Stanford University, Stanford, California, USA.

Stephanie J Schrag, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia, USA.

Jennifer R Verani, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia, USA.

Ryan E Wiegand, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia, USA.

Fernando Alarid-Escudero, Division of Public Administration, Center for Research and Teaching in Economics, Aguascalientes, Mexico.

Jeremy D Goldhaber-Fiebert, Department of Health Policy, Stanford University, Stanford, California, USA.

David M Studdert, Department of Health Policy, Stanford University, Stanford, California, USA; Stanford Law School, Stanford, California, USA.

Jason R Andrews, Department of Medicine, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, California, USA.

Joshua A Salomon, Department of Health Policy, Stanford University, Stanford, California, USA.

References

- 1. Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, et al. . Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med 2020; 383:2603–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Baden LR, El Sahly HM, Essink B, et al. . Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N Engl J Med 2021; 384:403–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Thompson MG, Burgess JL, Naleway AL, et al. . Prevention and attenuation of Covid-19 with the BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273 vaccines. N Engl J Med 2021; 385:320–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Angel Y, Spitzer A, Henig O, et al. . Association between vaccination with BNT162b2 and incidence of symptomatic and asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections among health care workers. JAMA 2021; 325:2457–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tenforde MW, Olson SM, Self WH, et al. . Effectiveness of Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines against COVID-19 among hospitalized adults aged ≥65 years—United States, January–March 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021; 70:674–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Haas EJ, Angulo FJ, McLaughlin JM, et al. . Impact and effectiveness of mRNA BNT162b2 vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 infections and COVID-19 cases, hospitalisations, and deaths following a nationwide vaccination campaign in Israel: an observational study using national surveillance data. Lancet 2021; 397:1819–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dagan N, Barda N, Kepten E, et al. . BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine in a nationwide mass vaccination setting. N Engl J Med 2021; 384:1412–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Britton A, Jacobs Slifka KM, Edens C, et al. . Effectiveness of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine among residents of two skilled nursing facilities experiencing COVID-19 outbreaks—Connecticut, December 2020–February 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021; 70:396–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cavanaugh AM, Fortier S, Lewis P, et al. . COVID-19 outbreak associated with a SARS-CoV-2 R.1 lineage variant in a skilled nursing facility after vaccination program—Kentucky, March 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021; 70:639–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chin ET, Ryckman T, Prince L, et al. . COVID-19 in the California state prison system: an observational study of decarceration, ongoing risks, and risk factors. J Gen Intern Med 2021; 36:3096–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine . Decarcerating correctional facilities during COVID-19: advancing health, equity, and safety. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Maner M. An analysis of interim COVID-19 vaccination plans. COVID prison project.2021. Available at: https://covidprisonproject.com/blog/data/data-analysis/an-analysis-of-interim-covid-19-vaccination-plans/. Accessed 15 March 2021.

- 13. Strodel R, Dayton L, Garrison-Desany HM, et al. . COVID-19 vaccine prioritization of incarcerated people relative to other vulnerable groups: an analysis of state plans. PLoS One 2021; 16:e0253208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chin ET, Leidner D, Ryckman T, et al. . Covid-19 vaccine acceptance in California state prisons. N Engl J Med 2021; 385:374–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. McCoy S, Bertozzi S, Sears D, et al. . Urgent memo COVID-19 outbreak: San Quentin prison. San Francisco, CA: Amend, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cameron D, Duarte C, Kwan A, McCoy S.. Evaluation of the April–May 2020 COVID-19 outbreak at California men’s colony. San Francisco, CA: Amend, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Andersen PK, Gill RD, Cox’s regression model for counting processes: a large sample study. Ann Stat 1982; 10:1100–20. [Google Scholar]

- 18. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. . The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet 2007; 370:1453–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. People with certain medical conditions. 2021. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/people-with-medical-conditions.html. Accessed 13 May 2021.

- 20. Vasileiou E, Simpson CR, Shi T, et al. . Interim findings from first-dose mass COVID-19 vaccination roll-out and COVID-19 hospital admissions in Scotland: a national prospective cohort study. Lancet 2021; 397:1646–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hitchings MDT, Lewnard JA, Dean NE, et al. . Use of recently vaccinated individuals to detect bias in test-negative case-control studies of COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness. medRxiv [Preprint]. July 2, 2021. Available from: doi: 10.1101/2021.06.23.21259415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Thomas SJ, Moreira ED, Kitchin N, et al. . Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA covid-19 vaccine through 6 months. N Engl J Med 2021; 385:1761–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gomes MGM, Gordon SB, Lalloo DG, Clinical trials: the mathematics of falling vaccine efficacy with rising disease incidence. Vaccine 2016; 34:3007–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lewnard JA, Tedijanto C, Cowling BJ, Lipsitch M, Measurement of vaccine direct effects under the test-negative design. Am J Epidemiol 2018; 187:2686–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ryckman T, Chin ET, Prince L, et al. . Outbreaks of COVID-19 variants in US prisons: a mathematical modelling analysis of vaccination and reopening policies. Lancet Public Health 2021; 6:e760–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. California Department of Public Health. Tracking variants: how has the proportion of variants of concern and variants of interest in California changed over time? 2021. Available at: https://www.cdph.ca.gov/Programs/CID/DCDC/Pages/COVID-19/COVID-Variants.aspx. Accessed 12 August 2021.

- 27. California State Government. COVID-19 Dashboard. Cases and deaths. 2021. Available at: https://covid19.ca.gov/state-dashboard/. Accessed 12 August 2021.

- 28. California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation. Population COVID-19 tracking: COVID-19 trends. 2021. Available at: https://www.cdcr.ca.gov/covid19/population-status-tracking/. Accessed 12 August 2021.

- 29. Chin ET, Leidner D, Zhang Y, et al. . Effectiveness of the mRNA-1273 vaccine during a SARS-CoV-2 Delta outbreak in a prison. N Engl J Med 2021; 385:2300–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.