The COVID-19 pandemic wreaked havoc on all aspects of life, especially in the post-acute and long-term care (PALTC) world. Now it is important to focus on the next phase of this journey, and we likely agree where it needs to start: How do we effectively begin to rebuild trust in PALTC? In nursing homes and assisted living facilities where relationships between leadership, staff, patients, and families have grown stronger during the pandemic, how can we continue that growth? And in facilities that still operate in a fear-based culture, how do we reverse that to allow for a stronger, more fulfilled workforce and improved patient care? The expertise that advanced practice providers (APPs), geriatricians, and medical directors who work in PALTC possess will be an integral piece in this journey.

In the spring of 2020, the highly infectious COVID-19 virus began its invasion into our nursing homes and assisted living facilities, which devastated the PALTC environment.1 Mortality in nursing home residents due to COVID-19 infection has been approximately 20%.2 There also was a significant mental and physical toll on nursing home staff. Recent data show more than 575,000 staff infections from COVID-19 and more than 1800 staff deaths due to this disease.2 In an industry where mistrust was extremely prevalent before the pandemic, these statistics, coupled with intense media attention on the PALTC industry, only added fuel to the fire and has inevitably led to further mistrust between residents and their families and the facilities/staff who care for them. This lack of trust and the negative underlying culture that can exist in PALTC facilities must be remedied to ensure the success of a person-centered PALTC system that we all envision. With a foundation of trust, we can then begin to address other issues that stem from mistrust, such as a culture of fear that exists in some facilities or a lack of confidence in safe immunizations.

The erosion of trust in the PALTC system in general has been escalating over the past few decades, and the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted 3 major causes of this distrust. The first, and possibly the most important area of concern, is the issue of adequate direct care and clinical staffing in PALTC. Addressing staffing issues, with a focus on frontline caregivers who ensure the residents’ safety and well-being, is critical. Limiting staff turnover in PALTC can improve the quality of care within a facility and needs to be a part of the solution.3 Programs that recruit and educate clinicians to work in this environment can greatly improve the care that is provided in nursing homes.4 Engaged APPs and medical directors who are certified and specialize in quality improvement, infection control, and leadership/culture building should be the standard we strive for in every facility.5

A second major cause of distrust is a lack of appropriate support and resources for staff, which was painfully evident during the height of the pandemic. The foundation of institutional trust must include investment in the well-being and health of both residents and staff. One such initiative is the Healing Together campaign of AMDA—The Society for Post-Acute and Long-Term Care Medicine, which consists of a multidisciplinary approach to improve the well-being of medical directors as well as frontline staff. The Kaiser Family Foundation/Washington Post Frontline Health Care Workers Survey published on April 6, 2021, further delineated the lack of support and resources for staff, showing 66% of frontline health care workers said their employer did “about the right amount” or “went above and beyond” by providing sick leave for employees who had COVID -19, but more than half of them stated their employers “fell short” when it came to providing additional pay for working in high-risk situations.6 Developing institutional trust is a multifaceted process that requires education initiatives, funding, and collaboration among different local, state, and national organizations. Investment in trust has yielded profound benefits in other industries that can serve as examples for improvement in our cultural workspace.7

A third barrier to promoting trust in PALTC is a lack of transparency and communication between the PALTC leadership, staff, and regulatory and policy-making bodies, and the people who live in PALTC communities. A lack of transparency by organizational leadership can create an undercurrent of mistrust that can lead to a sense of helplessness and powerlessness on the part of staff, residents, and family members. And as we saw during the vaccine roll-out, consistent, accurate information is critical to slowing the spread of rampant misinformation. PALTC leadership, with their organizational support, will need to prioritize transparency and communication at all levels to rebuild trust and replace fear with a sense of inclusion, recognition, and being valued. Facilities will need to consider and create means to help residents, staff, and their families process distressing circumstances.8

Communication between the facility and family members has been crucial during the COVID-19 pandemic. Inconsistent messaging is one of the fastest ways to destroy trust.8 When shared information is inconsistent, it leads to frustration and can be viewed as misleading.9 One effective method we propose to improve messaging/communication is the utilization of a town hall meeting. Residents and family members who have participated in town hall meetings have described them as a meaningful way to receive information, ask questions in real time, and be an active part of the community. Effective town hall meetings (which can also be virtual) include an authentic discussion of how the facility community is doing (struggles and successes) and demonstrates an active investment in resident, staff, and community life as well as the opportunity to address a specific topic such as vaccine hesitancy.10 Advocating for this openness and genuine honesty helps PALTC staff, residents, and families feel like they are a priority, and this active collaboration builds trust.

As we start to improve the quality and consistency of communication at the facility level, we must simultaneously collaborate with policy makers and regulatory leadership to ensure that expert, experienced voices are heard as policies are being debated and created. APPs, geriatricians, medical directors, and other clinical experts have been successful at this during the pandemic, and we need to maintain enthusiasm and active participation in these efforts. Patients and families need to know that their medical leaders are involved with the development of these policies and are putting the interests and well-being of their patients first. We must also continue to work with other state and national medical societies to craft clinical guidelines and educational materials, and coordinate outreach to policy makers. Promoting enhanced communication and transparency helps build public trust in nursing homes and can directly lead to staff pride, retention, and community support.11

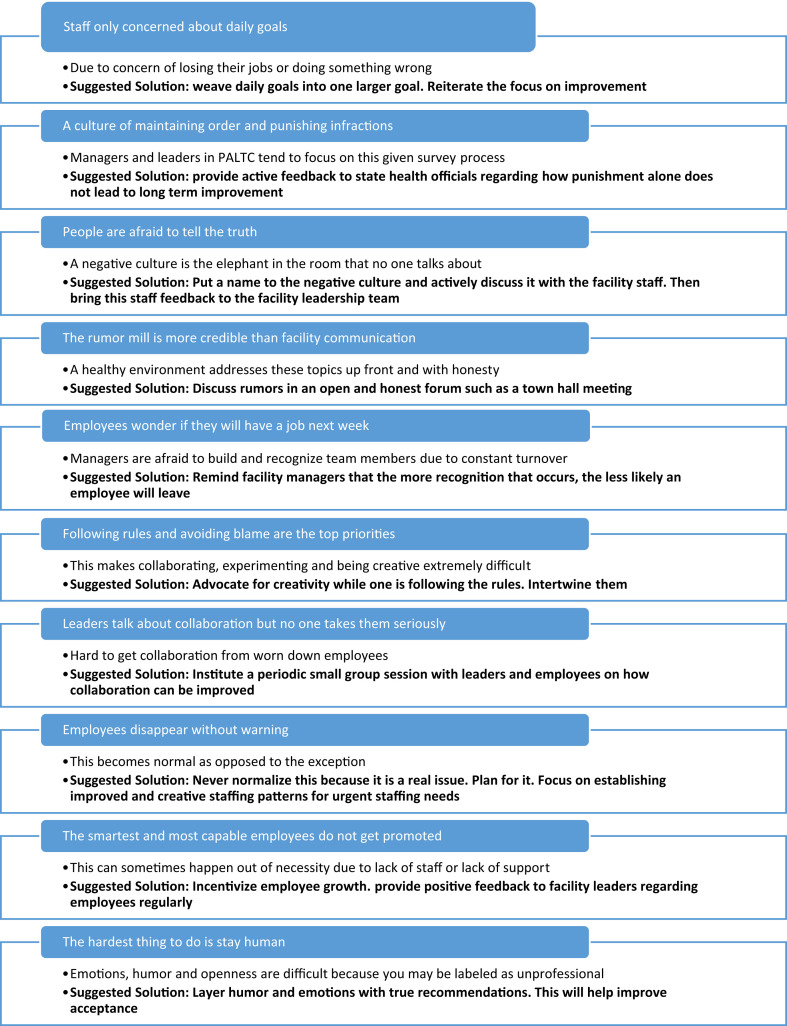

The punitive environment that has existed in nursing homes long before the pandemic also needs thoughtful revision and can be viewed as another cause of distrust.12 We need to move from being adversarial to collaborative and from punitive to helpful. Praising and encouraging positive behavior in staff is a necessary step in this change.13 PALTC will benefit tremendously if we consistently and enthusiastically adopt a culture of interdisciplinary team-based improvement, innovation, and safety. We can look to facilities that are accomplishing this as role models for others. We can also assess the facilities where we work to identify any underlying issues of fear and mistrust. Signs of a fear-based work culture are apparent within some PALTC facilities, and in some cases were especially evident during the COVID-19 pandemic.14 Some indications of a fear-based work culture are when staff are afraid to tell the truth to those in leadership positions, when the rumor mill overtakes credible information from leadership, or when following rules and avoiding blame take precedence over collaboration and creativity.14 Addressing the causes and establishing active solutions for a fear-based culture is the first step to building a foundation of trust. Drawing from the leadership literature, Figure 1 presents signs of a fear-based work culture and suggested solutions for tackling them, including improved communication techniques, active feedback, and positive reinforcement.14 , 15

Fig. 1.

Characteristics of a fear-based work culture and proposed solutions (adapted from the Forbes article entitled “Ten Unmistakable Signs of a Fear-Based Workplace”).14,15

Build a Foundation of Trust Through Strong Leadership

Trust-building can be viewed from 4 different perspectives: interpersonal, institutional, organizational, and public trust.16 A good leader knows that human interaction is the driving force behind an organization and can motivate people to accomplish a common goal. Leading through kindness and compassion is vital to helping an organization thrive. Leading through love and kindness as opposed to fear is necessary for the organization to achieve its highest level of functioning.17 This can help maximize an organization’s positive impact on both society and the individual, which is paramount in the health care industry. The American Board of Internal Medicine has dedicated years of research to discover effective strategies to build trust within our health care system. These strategies can be applied to PALTC settings to enhance and elevate care and staff satisfaction, as well as to increase effectiveness for other facility goals, such as promoting COVID-19 vaccine confidence. One of the most compelling ways to effectively build interpersonal trust is to recognize that trust-building is “dose dependent.”16 Trust not only necessitates active listening but invites collaboration and is pursued with intention. Building a trusting relationship must also include the acknowledgment of each person’s value and is further created on a foundation of dignity and respect. Building trust is personal.

The Mayo Clinic has further outlined the process of building trust by using a leadership index that describes 5 trust-generating leader behaviors: inclusion, transparency, solicitation of input and ideas, support for professional development, and expression of appreciation and gratitude.18 Interpersonal trust not only has extrinsic value in the facilitation of quality of care, but it also has intrinsic value. There are several other factors that are needed to promote interpersonal trust, both between residents and staff and between staff and leadership: (1) a sense of situational awareness, (2) the ability to notice and respond, (3) understanding expectations, (4) predictable follow through and being intentional with communication, and (5) addressing inequality in power. We need to educate ourselves on these aspects as medical directors, providers, politicians, and administrators, and include the entire interdisciplinary team to improve our collaborative efforts and make them more effective. Another challenge is that trust is not distributed equally and there is a disproportionate amount of distrust that falls on those who have less power or are from marginalized communities. Without first confronting the inequities that exist across health care systems, distrust cannot be fully overcome.16

By design, PALTC settings are also personal. We are sitting in our patients’ “living rooms” with nurses, certified nursing assistants, therapists, and others. Residents who trust staff feel more at home and secure about their living location and care.11 They are more comfortable with accepting help with toileting and bathing and more likely to communicate changes in their health,19 whereas residents who do not have trust have increased depression and isolation.19 For patients without family living nearby, staff become their family. And for staff who endured the uncertain, exhausting days of the worst months of the pandemic together, they often think of each other as their “second” families. These are powerful relationships that must be respected and cherished.

Active trust-building solutions and combating a fear-based culture that sometimes exists in PALTC is a necessity after this pandemic. The PALTC community gained and solidified the trust of other health care and government organizations, media, and legislators during the pandemic. Using these strengthened relationships and the strategies put forth in this article, geriatricians, APPs, and medical directors can affect significant and lasting change in PALTC. Going forward, our expertise and passion to improve care for older adults in PALTC is essential to developing a better system for all of us. It is our moment to lead.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Ochieng N., Chidambaram P., Garfield R., Neuman T. Factors associated with COVID-19 cases and deaths in long-term care facilities: findings from a literature review. 2021. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/factors-associated-with-covid-19-cases-and-deaths-in-long-term-care-facilities-findings-from-a-literature-review/ Kaiser Family Foundation.

- 2.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services COVID-19 nursing home data. https://data.cms.gov/stories/s/bkwz-xpvg [PubMed]

- 3.Castle N.G., Engberg J., Men A. Nursing home staff turnover: impact on nursing home compare quality measures. Gerontologist. 2007;47:650–661. doi: 10.1093/geront/47.5.650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abe K., Kawachi I. Deaths in nursing homes during the COVID-19 pandemic—lessons from Japan. JAMA Health Forum. 2021;2:e210054. doi: 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2021.0054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rowland F.N., Cowles M., Dickstein C., Katz P.R. Impact of medical director certification on nursing home quality of care. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2009;10:431–435. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2009.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kirzinger A., Kearney A., Hamel L., Brodie M. KFF/The Washington Post Frontline Heath Care Workers Survey. https://www.kff.org/report-section/kff-the-washington-post-frontline-health-care-workers-survey-toll-of-the-pandemic/

- 7.Frei F.X., Morriss A. Begin with trust. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2020/05/begin-with-trust May-June 2020 issue.

- 8.SAMHSA’s Trauma and Justice Strategic Initiative . July 2014. SAMHSA’s concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma-informed approach. US Department of Health and Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galford R.M., Drapeau A.S. The enemies of trust. Harvard Business Review Magazine. 2003. https://hbr.org/2003/02/the-enemies-of-trust [PubMed]

- 10.Barry S.D., Johnson K.S., Myles L., et al. Lessons learned from frontline skilled nursing facility staff regarding COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69:1140–1146. doi: 10.1111/jgs.17136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gilbert A.S. Conceptualizing trust in aged care. Aging and Society. 2021;41:2356–2374. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nazir A., Steinberg K., Wasserman M., et al. Time for an upgrade in the nursing home survey process: a position statement from the Society for Post-Acute and Long-Term Care Medicine. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21:1818–1820. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nazir A., Zimmerman S., Meyer M.L. No one cares when planes don't crash: the message for long-term care. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2019;20:583–585. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2019.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ryan L. Ten unmistakable signs of a fear-based workplace. https://www.forbes.com/sites/lizryan/2017/03/07/ten-unmistakable-signs-of-a-fear-based-workplace/?sh=7dcf9d011e26 Forbes Online. May 7, 2017.

- 15.Keegan S.M. 1st ed. 2015. The Psychology of Fear in Organizations: How to Transfer Anxiety into Well-Being, Productivity and Innovation. Kogan Page. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lynch T. ABIM Foundation Forum background paper on re-building trust. 2019. https://abimfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/2019-ABIM-Foundation-Forum-Background-Paper.pdf

- 17.Wickman H.H. 2nd ed. 2018. The Evolved Executive: The Future of Work is Love in Action. Lioncrest Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lynch T. 2019. ABIM Foundation Forum Summary Paper.https://abimfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Forum-2019-Summary-Paper_Draft-2b.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bradshaw S.A., Playford E.D., Riazi A. Living well in care homes: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Age Ageing. 2012;41:429–440. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afs069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]