Abstract

For youth and adults of color, prolonged exposure to racial discrimination may result in debilitating psychological, behavioral, and health outcomes. Research has suggested that race-based traumatic stress can manifest from direct and vicarious discriminatory racial encounters (DREs) that impact individuals during and after an event. To help their children prepare for and prevent the deleterious consequences of DREs, many parents of color utilize racial socialization (RS), or communication about racialized experiences. Although RS research has illuminated associations between RS and youth well-being indicators (i.e., psychosocial, physiological, academic, and identity-related), findings have mainly focused on RS frequency and endorsement in retrospective accounts and not on how RS is transmitted and received, used during in-themoment encounters, or applied to reduce racial stress and trauma through clinical processes. This article explores how systemic and interpersonal DREs require literate, active, and bidirectional RS to repair from race-based traumatic stress often overlooked by traditional stress and coping models and clinical services. A novel theory (Racial Encounter Coping Appraisal and Socialization Theory [RECAST]), wherein RS moderates the relationship between racial stress and self-efficacy in a path to coping and well-being, is advanced. Greater RS competency is proposed as achievable through intentional and mindful practice. Given heightened awareness to DREs plaguing youth, better understanding of how RS processes and skills development can help youth and parents heal from the effects of past, current, and future racial trauma is important. A description of proposed measures and RECAST’s use within trauma-focused clinical practices and interventions for family led healing is also provided.

Keywords: racial socialization, African American families, RECAST, race-based traumatic stress, clinical healing

When my mother says get home safe

her voice is the last coin she owns,

and everything is a wishing well.

She is praying to every god she can find

that a cop does not

make a hashtag out of my body.

Racial discrimination—or the unfair and prejudicial treatment based on racial demographic characteristics (American Psychological Association [APA], 2013)—remains a powerful and harmful reality in the United States (APA, 2013). Within a month of the 2016 presidential election, nine out of 10 educators who replied to a voluntary survey reported witnessing emotional and behavioral changes in students, with over 1,000 incidents attributed to discrimination based on race and immigration (Southern Poverty Law Center, 2016). In particular, empirical findings demonstrated that the overwhelming majority (i.e., 90%) of African American adults and children report discriminatory racial encounters (DREs; Helms, Nicolas, & Green, 2012; Pachter, Bernstein, Szalacha, & García Coll, 2010). Although many explicit forms of racial discrimination are now illegal, blatant and subtle DREs that negatively impact youth of color are propagated through various systems and quickly amplified through the Internet (Tynes, Giang, Williams, & Thompson, 2008). These DREs, which can occur at interpersonal, institutional, and systemic levels (Harrell, 2000), include suspensions and expulsions within schools (Skiba & Williams, 2014), racial profiling (A. Thomas & Blackmon, 2015), and killings by police and authority figures (Buehler, 2017), to name but a few. It is important to note that families and mental health professionals struggle to protect and affirm children of color exposed to these events (see Fischer & Shaw, 1999), particularly given that racial stress reactions often accompany DREs and, if left unaddressed, may lead to trauma that can have debilitating effects on health and well-being (Carter, 2007).

In light of the negative stress effects of recently increasing racial hostility in the American social climate, scholars have called for culturally grounded theories, healing practices, and interventions that effectively capture how people cope with and reduce the symptoms of racially stressful encounters (Williams & Medlock, 2017). Families have used racial socialization (RS)—or communication about racial dynamics—as an approach to help youth cope with DREs and develop healthy racial identities (Hughes et al., 2006). In this article, we advance the Racial Encounter Coping Appraisal Socialization Theory (RECAST) as a theoretical enhancement to the current literature on RS by proposing that the relationship between racial stress and coping is explained by racial coping self-efficacy, which is moderated by RS competency. We propose that, as a moderator, RS must promote a form of literacy that is more user-friendly, planned, and responsive in managing DREs. Through literacy, the definition of RS is broadened to include the explicit teaching and implementation of racially specific emotional regulation and coping skills that can be observed, trained through a lens of competency, and evaluated in specific interventions. We also point to and call for burgeoning efforts (e.g., an intervention and measure) that use RECAST’s reframing of RS to respectively better combat and understand race-based traumatic stress for youth and parents.

Race-Based Traumatic Stress

Harrell (2000) defined racism-related stress as “race-related transactions between individuals or groups and their environment that emerge from the dynamics of racism and that are perceived to tax or exceed existing individual and collective resources or threaten well-being” (p. 44). Such race-based traumatic stress can be due to direct (or firsthand) and vicarious (or secondhand) DREs (Carter et al., 2013; Jernigan & Daniel, 2011). Research has demonstrated a link between race-related stress and anxiety disorders (Soto, Dawson-Andoh, & Belue, 2011), cardiovascular reactivity (Williams & Leavell, 2012), poor immunological functioning (Sawyer, Major, Casad, Townsend, & Mendes, 2012), and various facets of sleep disturbance (Adam et al., 2015), all symptoms that can impact daily functioning.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.) criteria assert that people must directly experience or witness an event to be diagnosed with posttraumatic stress disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Despite many DREs not meeting these criteria, individuals may experience debilitating psychological symptoms from distant racial encounters. To be sure, studies have found effects from both direct (e.g., rumination, anger, overidentification, emotional suppression, or avoidance; Hoggard, Byrd, & Sellers, 2012; Soto et al., 2011; Terrell, Miller, Foster, & Watkins, 2006) and vicarious (e.g., anxiety, depression; Tynes et al., 2008) DREs. Whether experienced directly or vicariously, DREs present significant challenges to youth of color and their parents given that they are constantly exposed to the insidious stressor (e.g., Comas-Díaz, 2016). As such, parents may feel underprepared to address in-the-moment DREs. Active responses to racial threat are physiologically exhausting for targets of discrimination (Richeson & Trawalter, 2005) and, given anxiety-based avoidant responses to overwhelming and threatening racial encounters (Gudykunst, 1995), require advanced understanding and practice to navigate.

Racial Socialization as a Buffer to Race-Based Traumatic Stress

Raising children to effectively cope with the stress inherent in peer, schooling, neighborhood, and virtual ecologies is a basic competence demand for parenting accomplished through socialization (Kliewer, Fearnow, & Miller, 1996). Racial socialization, furthermore, has been conceptualized as the verbal and nonverbal racial communication between families and youth about racialized experiences (Lesane-Brown, 2006). Although some discrepancies exist within the RS literature over the past four decades, research has generally found positive associations between parents’ frequent use of RS and a host of youth well-being indicators (i.e., psychosocial, physiological, academic, identity; Hughes et al., 2006). RS studies have typically focused on the extent to which the frequency of a single type or combination of RS message(s) predict(s) psychosocial well-being (e.g., externalizing behavior; Rodriguez, McKay, & Bannon, 2008), academic outcomes (e.g., educational aspiration; Wang & Hughley, 2012), self-esteem (Murry, Berkel, Brody, Miller, & Chen, 2009), and/or racial identity (e.g., public regard; McGill, Hughes, Alicea, & Way, 2012; Stevenson & Arrington, 2009). Although the histories of racial and ethnic immigration, discrimination, and political engagement in the United States represent different socialization themes for different racial and ethnic groups (Huynh & Fuligni, 2008; Seol, Yoo, Lee, Park, & Kyeong, 2016), this article illustrates experiences of racial discrimination and socialization for African American families given the preponderance of literature detailing the detrimental impact of discrimination on and protective qualities of racial socialization in this population.

Optimally, the greatest benefit to youth’s psychological well-being would be the eradication of racism. As it currently stands, however, RS has been largely identified as a protective factor against persistent and deleterious effects of racial discrimination (Spencer, Dupree, & Hartmann, 1997) wherein parents provide their children with verbal and/or behavioral messages of four primary content types: cultural socialization (cultural pride), preparation for bias (discriminatory preparation), promotion of mistrust (wariness regarding interracial encounters), and egalitarianism-silence about race (mainstream orientation or racial avoidance; see Hughes et al., 2006). Parents provide strategies in which they often use both protective (e.g., preparation for bias) and affirmational (e.g., cultural socialization) RS to navigate potentially challenging racial terrain (Harris-Britt, Valrie, Kurtz-Costes, & Rowley, 2007).

Most parents, however, use preparation for bias reactively, or, for example, after discovering that their child has been treated unfairly at school because of race (White-Johnson, Ford, & Sellers, 2010) or following a highly publicized racial assault (e.g., the stalking and fatal shooting of Trayvon Martin; A. Thomas & Blackmon, 2015). During these conversations, parents often communicate fears for their children’s safety (Coard, Foy-Watson, Zimmer, & Wallace, 2007), information about the history of domestic racial terrorism (Thornhill, 2016), a recounting of personal DREs (Crouter, Baril, Davis, & McHale, 2008), and/or information about general and racial coping strategies (Stevenson, Davis, & Abdul-Kabir, 2001). Preemptive conversations, however, may afford youth greater psychological protection relative to reactive approaches (Derlan & Umaña-Taylor, 2015; D. E. Thomas, Coard, Stevenson, Bentley, & Zamel, 2009).

In addition to these discussions, youth are also powerfully affected by their parents’ behaviors (e.g., protests). In silent or physical practices, RS can be said to be occurring, and children can make meaning of these subtle or direct communications (Caughy, Nettles, Lima, & 2011). What is less known is whether parents explain why they choose to protest or ignore, so that youth can be more accurate in understanding why parents find these communications important. Ostensibly, the more youth know explicitly why parents use RS and for what purpose, the more they can effectively use what they learn to combat systemic, domestic, and interpersonal DREs in developmentally appropriate ways. Although theories have conceptualized in what context socializing African American youth may be necessary (e.g., triple quandary theory; Boykin & Toms, 1985), current theories are sorely lacking with respect to how the transmission of RS reduces youth’s stress in DREs and buffers against erosion to their well-being outcomes (e.g., process model of ethnic-racial socialization; Yasui, 2015).

Racial Socialization From a Legacy Approach

Extant literature is replete with the potential mental health and academic benefits associated with frequent delivery of RS (Neblett, Philip, Cogburn, & Sellers, 2006; Reynolds & Gonzales-Backen, 2017); however, prior research has been based almost exclusively on recall of the frequency and content of racial messages that parents communicate and youth receive within a given time span (Hughes et al., 2006; Lesane-Brown, 2006). Stevenson (2014, p. 118) noted that this approach to RS emphasizes a “legacy” form of communication that focuses on the subtypes as beliefs, attitudes, and messages that are ideological and historical. Such an approach assumes that declarative and static parental communication leads not only to youth’s awareness and knowledge about race and racial dynamics but also to effective coping behaviors. However, this notion that parental communication leads directly to knowledge and coping efficacy underappreciates the bidirectional, reciprocal nature of RS between youth and parents (e.g., Hughes & Chen, 1999) and the complexity of the emotional, process-oriented coping strategies needed to resolve past, in-the-moment, and future racial conflicts (Stevenson, 2017). For example, parents must deconstruct history and personally relevant events, make meaning of them, and discern both what content to communicate to their children and how they will communicate that content in the service of helping their children navigate racial dynamics. In turn, children must decipher, make meaning of, and apply the content of the verbal and behavioral messages that they receive from their parents. For families to collectively tackle the traumatic effects of DREs, greater understanding of the mechanisms involved in the meaning making of RS transmission is necessary. A legacy approach to RS has been mostly aspirational and informational by emphasizing the importance of knowledge of racial dynamics, strengths, and challenges in promoting racial coping but has not targeted the skills necessary to bring about the coping behaviors parents hope will protect children from DREs’ stressful and traumatic effects.

Theorizing Racial Socialization Through a Literacy Approach

Literacy refers to the ability to read and write, which requires an understanding of a particular language as well as how to decode the communication tools or text of that language (Byrne & Fielding-Barnsley, 1995). Racial literacy is the ability to accurately read (e.g., decode, interpret, appraise), recast (e.g., reappraise or rewrite stereotyped narratives), and resolve (e.g., engage in healthy decision making) the language of racially stressful encounters (Stevenson, 2014). It is posited that DREs represent a narrative about race relations in this country: DREs are scripts signifying multidimensional, omnipresent, predictable, and emotionally stressful interactions (Worrell, Vandiver, Schaefer, Cross, & Fhagen-Smith, 2006). It is asserted that RS must become a literacy-focused strategy that involves the practiced encoding, decoding, interpretation, and transmission of intellectual, emotional, and behavioral beliefs and skills regarding these matters. As a form of literacy, RS functions in this context to enhance youth’s and adults’ ability to read and recognize DREs, protect and affirm their progressive development of individual and collective racial coping self-efficacy, stimulate effective reappraisals of racially stressful encounters as workable, and promote successful engagement in and resolution of conflict-laden racial interactions. To successfully navigate these encounters, families must translate these scripts, investigate how congruent they are with their own narratives of humanity, and jettison dehumanizing meanings. Given this assertion, how must one modify RS to be able to evaluate its effectiveness in developing youth behaviors that reduce the stress and trauma from DREs?

Transitioning From a Legacy to Literacy Approach

A practical RS leads to an individual or group’s being able to accurately, quickly, and healthfully read, recast, and resolve the emotional text and subcodes of a racial situation and the actors involved. Whereas legacy RS endeavors to describe the state of race relations and offers general maxims as advice for coping with race-related realities (e.g., “As a Black person, you have to work twice as hard to be considered half as good as Whites”), a literacy approach focuses on youth’s ability to agentically read, rehearse, recall, and successfully enact direct, anticipatory, and practiced approaches with caretakers in their efforts to navigate DREs (e.g., “It can feel painful when someone is treating you as racially inferior, but just remember it’s based on a false myth of superiority and is meant to be destructive to your definition of yourself, your family, your people, and your culture, so you can choose any of the strategies we’ve rehearsed to reject that inferiority”). A literacy approach to RS investigates how competently and efficaciously parents and youth can transmit and youth then execute coping strategies for predictable distal or proximal DREs. Thus, a literate perspective of RS centers on how prepared youth are to see, speak to, emote about, remain mindful of, and implement a variety of racially literate skills learned from RS transmission with parents in the face of racially fraught moments.

Racial Encounter Coping Appraisal and Socialization Theory

Stevenson (2014) offered RECAST as a frame for conceptualizing how youth and families anticipate, process, and respond when confronted by racially stressful encounters. RECAST is the racially specific complement to Lazarus and Folkman’s transactional model of stress and coping (TMSC; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984) by asserting that RS is a critical factor in how individuals reduce the stress associated with DREs. This conceptual frame also suggests that explicit and practiced RS improves one’s confidence and competence to employ multiple conflict resolution options for improved long-term well-being outcomes.

In the TMSC, a stressor is a demand requiring action to reduce the imbalance in resources and demands. The model attends to how stressors are appraised (e.g., threat, challenge, or insignificant), the extent to which individuals believe that they have the capacity to control or manage the stressor (e.g., coping self-efficacy), the nature of the individual’s efforts to cope with the stressor (e.g., meaningbased coping), and the extent to which employed coping strategies yield desired results (e.g., positive or negative outcomes; Provencher, 2007). Although several researchers have situated racial discrimination in stress and coping paradigms (Clark, Anderson, Clark, & Williams, 1999; Harrell, 2000; Major, Kaiser, O’Brien, & McCoy, 2007), how this stress relates to RS has not yet been theorized. Furthermore, scholars have argued that the TMSC does not fully appreciate dyadic stress and coping processes inherent in familial environments (Bodenmann, 1997). Bodenmann (1997) described an element of dyadic coping particularly salient for RS, that is, that the supportive dyadic coping from one family member to another (e.g., parent to child) may inevitably serve as a reduction in parental stress, especially through a trauma-focused lens. As such, a racial stress and coping theory requires youth’s attention to initial appraisals of racialized events as threatening or challenging to receive supportive dyadic coping from their parent(s). Likewise, parents must have skills and efficacious beliefs in themselves to reduce their own stress prior to effectively attending to their children via the transmission of supportive coping strategies. Thus, RECAST integrates the dyadic and racial components missing from the TMSC and utilizes RS as a strengths-based protective factor.

Elements of RECAST

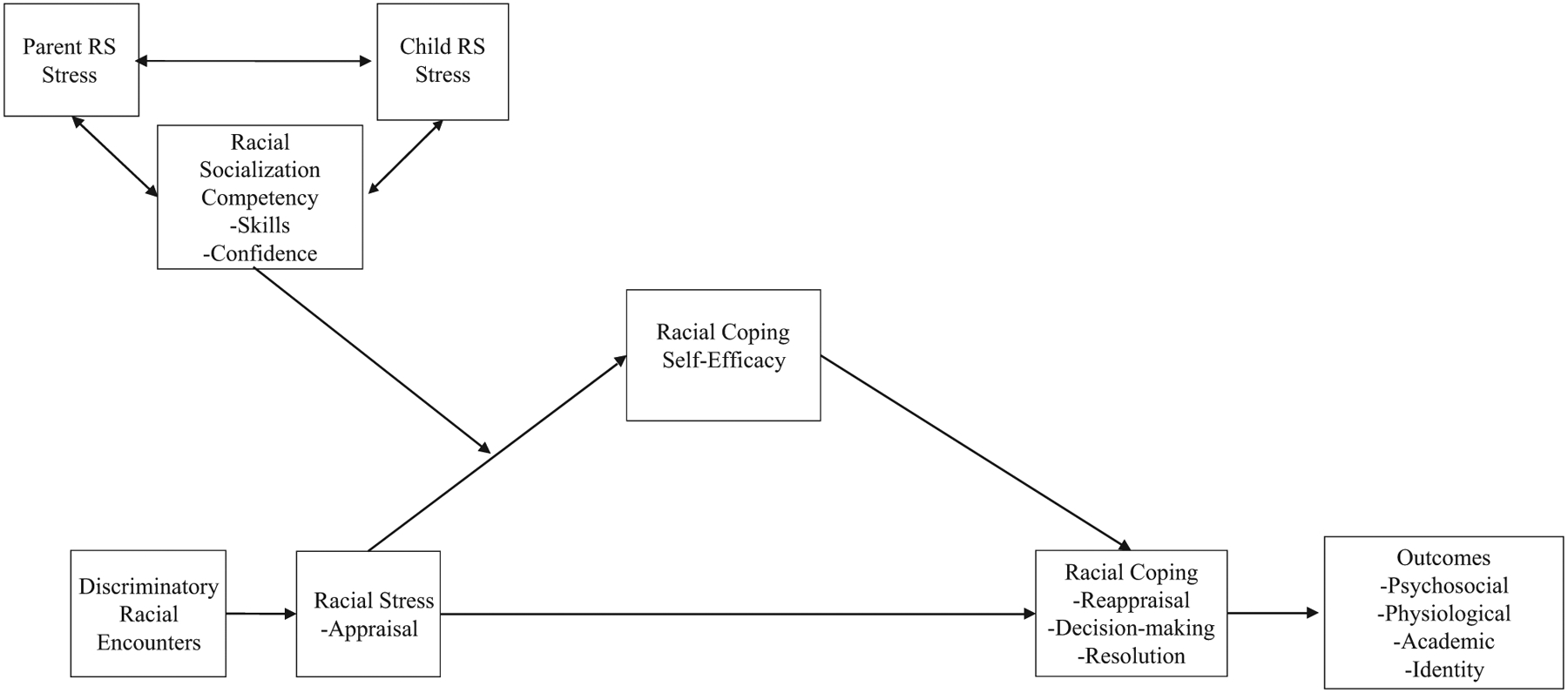

The developmentally flexible RECAST model (see Figure 1) asserts that coping with race-related stressors requires a dynamic and cyclical process wherein events are perceived and read with respect to their appraisal as DREs. Pertaining to the TMSC, there are two types of appraisal: primary appraisal refers to whether an event, in this case a DRE, is a threat. Secondary appraisal refers to an assessment of one’s coping resources available to match the demands of the stressor. In RECAST, the identification of a DRE as racial or not is important and is best understood as occurring during primary appraisal processing at the moment of the DRE. For the sake of clarity in the description of RECAST, we assume that the parent and child would perceive the DRE as a racial threat, and thus the RS interaction or conversation would occur in light of the potential threat. Moreover, the secondary appraisal process occurs at evaluation of one’s self-efficacy or coping resources to engage a DRE effectively. The relationship between DRE stress and coping (reappraisal, decision-making, and resolution) is believed to be mediated by parents’ and children’s confidence and expectations of the outcome of coping effectively with DREs. In no previous work has racial coping self-efficacy been posited to mediate the relationship between DRE stress and coping, where RS competency is theorized to moderate the role of self-efficacy. Next, each element of the model is elaborated upon.

Figure 1.

The moderating role of racial socialization in stress, self-efficacy, and coping processes through the Racial Encounter Coping Appraisal and Socialization Theory (RECAST). RS = racial socialization.

Perceiving DREs and their stressfulness as racial is key to becoming literate given that DREs can be seen accurately, inaccurately, or not at all (Clark et al., 1999). One must have knowledge that DREs are possible, can occur at multiple levels, and are between various actors. RECAST asserts that racial stress appraisal allows people to recognize that the encounter is racial; to become aware that the encounter creates in one’s self and others cognitive, emotional, and physiological reactions; and to recognize that those reactions can occur during and after the encounter. Assessing the extent and intensity of these reactions is important in determining if any potential threat is present for any given DRE.

Racial coping self-efficacy

Racial coping self-efficacy is the belief or confidence in one’s ability to resolve racially stressful encounters and is foundational to the application of one’s intended actions (e.g., Schwarzer & Renner, 2000). If coping self-efficacy is what individuals believe they can manage during racially stressful moments, then coping is what they do to demonstrate that management. But what one does and what one believes can be done are different (e.g., Weisz, 1986). Thus, self-efficacy is central to reappraising an experience to confidently believe in its manageability while one determines how to overcome it. The focus on building racial coping self-efficacy is through the use of cognitive-behavioral-based mindfulness (e.g., attentional self-regulation and orientation; Bishop et al., 2004) and stress reduction during and after DREs (e.g., Woods-Giscombé & Black, 2010). Racial self-efficacy addresses the sense of helplessness during DREs by improving one’s confidence and increasing the availability of multiple decisions (Bandura, 1997).

Racial socialization competency—

Racial socialization competency—or how well families are skilled and confidently prepared to engage in RS communication—is a crucial element of RECAST. This is a key difference between the legacy and literacy approaches: instead of the attitudinal importance or frequency of RS messages that are central to legacy RS, the focus of this aspect of RECAST is on how well racially socialized coping skills for DREs are understood, transmitted, received, and/or implemented. A competency perspective to RS is consistent with other literatures that assess the development rather than solely the frequency of the skill (e.g., parent training; Pisterman et al., 1992). Although the four subtypes (e.g., cultural socialization) of RS are still relevant within the competency perspective, RECAST argues that families transmitting RS messages can develop an increased sense of competence when skills and confidence are also considered as components of RS (Anderson, Jones, & Stevenson, 2018).

Racial socialization stress

Racial socialization stress is rarely discussed within the literature; however, it can be rather stressful for parents to talk to children about race (Bentley, Adams, & Author, 2009; Hamm & Coleman, 2001). Conversely, it may be equally difficult for youth to solicit, correct, or receive race-related communication from parents and other providers (Hughes & Johnson, 2001). Therefore, a key goal of RECAST is to account for how well competent RS helps to reduce the stress in racial communication. Personal (e.g., parental history of DRE coping) and contextual dimensions of DRE complicate how the conversations are transmitted between parent and child. Moreover, not all parents want to talk to children about racial matters or see it as meaningful to well-being and may be fearful of these conversations (Hughes et al., 2006). Because it is stressful to engage in racial discussions, both parents and children might approach initiating and responding to these conversations with varying degrees of hesitation and reticence. For those parents and youth who use emotion-focused rather than problem-focused approaches to manage the stress of racial conversation, they may be more prone to avoiding or not persisting through progressive racial discussions. This avoidance could undermine the level of competency in the delivery and acquisition of RS literacy skills. As such, it is important to determine how well parents have historically managed their own stress appraisal, reappraisal of, and coping with DREs. Additional considerations (e.g., parental delivery based on life experiences; child reception and application given age, sex, and comprehension ability) are also important regarding RS stress levels.

Coping

Coping is defined as “the cognitive and behavioral efforts made to master, tolerate, or reduce external and internal demands and conflicts among them” (Folkman & Lazarus, 1980, p. 223). Both adaptive and maladaptive coping (e.g., approach, accommodation, self-help, avoidance, and self-punishment; Zuckerman & Gagne, 2003) are at anyone’s disposal. The latter two strategies represent maladaptive approaches that are frequently utilized in stressful DREs (Clark et al., 1999). Given that parents often socialize youth to cope with general stressors explicitly (e.g., coping socialization), families would also need to racially socialize themselves with adaptive racial coping strategies specific to racial stressors (Anderson, Jones, Anyiwo, McKenny, & Gaylord-Harden, 2018). Racial coping is defined as learning to positively reappraise a DRE as less threatening and make decisions during racial encounters that are choices, not reactions; more problem-focused than emotion-focused; and more likely to be healthy and productive to one’s sense of self and management of the DREs. Although research has found that greater RS frequency is associated with racial identity centrality (Stevenson & Arrington, 2009) or academic achievement (Hughes, Witherspoon, Rivas-Drake, & West-Bey, 2009; Neblett et al., 2006), intermediate coping variables may explain why these outcomes are present. Through RECAST, it is posited that racial coping, including reappraisal, decision-making, and resolution, predicts youth well-being outcomes (Anderson, McKenny, Mitchell, Koku, & Stevenson, 2018; Scott, 2003).

Given that accurate appraisal of the encounter as racial leads to assessing one’s ability to manage thoughts, behaviors, and emotional reactions (social cognitive theory; Bandura, 1997), racial coping reappraisal refers to cognitive strategies for reevaluating a situation to determine its threat potential and manageability. In the same way a stressor must be initially appraised as a threat, challenge, or insignificant occurrence, reappraisal allows for an evaluation of the stressor as “benign, beneficial, and/or meaningful” (Garland, Gaylord, & Fredrickson, 2011, p. 60). It is akin to the concept of benefit finding (Affleck & Tennen, 1996), which refers to cognitive-behavioral coping strategies that enable the individual to potentially appraise a difficult situation as manageable (e.g., Fava, Rafanelli, Cazzaro, Conti, & Grandi, 1998; Folkman & Moskowitz, 2000). Through reappraisal, the experiences of DREs become predictable, modifiable, and illuminating of the limits and strengths of one’s context and one’s abilities. Positive reappraisal, then, is about empowerment, agency, and control in addressing a stressor as a workable challenge rather than a paralyzing threat or avoidant-laden insignificant event through a reexamination of internal and external resources (Garland et al., 2011). As an empowerment strategy, coping reappraisal also stands in contrast to the attenuation and habituation of repeated exposure to stressful and traumatic DREs which may lead to acceptance of and hopelessness regarding racial conditions.

Although the anticipation of negative outcomes of DREs can spiral toward psychological positions of paralysis and uncertainty (Gudykunst, 1995, 2005; Gudykunst & Shapiro, 1996), this anxiety can also be modified to activate effective coping skills that lead to rewarding racial encounters (Stevenson, 2014). If anxiety can trigger threat or challenge, then racial coping decision-making becomes a tool for defining potential and multiple resolutions to the racial encounter. Besides a benefit of positive reappraisal, having multiple options and decisions reframes DREs and the actors as more predictable. This could explain why scripting, rehearsal, and role-playing common racial moments using different choice points can reduce the uncertainty that undermines one’s confidence in decision-making (Avery, Richeson, Hebl, & Ambady, 2009).

Resolution

Resolution of racial stress involves individuals making healthy decisions that are neither an under- nor an overreaction during and after a DRE. For example, to appraise a DRE as mild (e.g., a 4 on a scale of 1–10) when it is actually experienced viscerally and physically as extreme (e.g., a 9) would make resolution of the conflictual stress difficult. The coping literature would suggest that the more successful individuals are in accurately evaluating and resolving a stressful DRE, the more positive their well-being outcomes (Folkman, 2013). As such, options presented from RECAST include youth’s engagement with the stressor or perpetrator to the extent that psychological discomfort would be moved away from their internalizing mechanisms to problem-focused and assertive thoughts and behaviors (e.g., letters, legal advocacy).

Outcomes

Outcomes from the aforementioned coping processes are anticipated to be more predictable than are some of the mixed findings inherent in current legacy approaches to RS (see Hughes et al., 2006). Indeed, the frequent use of RS does not consistently produce positive outcomes for youth simply by virtue of its presence in one’s upbringing, social networks, or learning environments. To best explain subsequent and long-term psychological, academic, identity, and self-esteem outcomes, the field should conceptualize the process-oriented nature of the relationship between DRE stress, self-efficacy, coping, and RS for acquiring the accompanying skill sets necessary to competently navigate encounters. Although RS is related to these outcomes, it is posited to be through the mechanism of enhanced efficacy and coping processes that provide the cognitive and behavioral elements critical for youth comprehension and implementation. At the conclusion of a RECAST-informed feedback loop, parents and youth can evaluate to what extent their response to a DRE has improved. If it is indeed better than for other experiences they previously had, the outcomes will help to inform stress, efficacy, RS competency, and coping during the next set of racialized experiences.

As such, a testable set of hypotheses of this model includes the following:

Hypothesis 1: DRE stress will have a negative direct relationship with racial coping.

Hypothesis 2: This relationship will be significantly reduced or eliminated via racial self-efficacy.

Hypothesis 3: The role of the mediator will be moderated by levels of RS competency. We expect that self-efficacy will be enhanced for parents and youth who endorse high levels of RS competency relative to those who endorse low levels of RS competency.

Hypothesis 4: The moderated mediation of DRE stress, coping, self-efficacy, and RS competency will be predictive of youth outcomes.

RECAST in the Real World

One of the more challenging duties for African American parents is when and what to say to their children about how to respond if they come in conflictual contact with police. Communication about how to respond to the police comes in verbal and nonverbal forms but is generally referred to as “The Talk”. In one example of The Talk, The New York Times focused on a Black high school adolescent stopped no fewer than 60 times as a result of New York City’s highly scrutinized practice of “stop-and-frisk” (Dressner & Martinez, 2012). In its video documenting the experience of Tyquan, The New York Times revealed the adolescent’s immediate confusion upon his first police stop. He stated, “I thought you had to do something for them to really stop you, but after that, I seen (sic) that you didn’t have to do nothing to get stopped.” The realization that he was not being stopped because of any wrongdoing on his part led Tyquan to perceive his subsequent stops as racially motivated.

Tyquan spontaneously described his appraisal of his stress during the DRE. He answered the question of whether the racial stress was a challenge (i.e., difficult but manageable) or a threat (i.e., difficult and potentially dangerous) by indicating that when he asked the officers why he was being stopped, he felt “threatened” by them. In the reappraisal process, he assessed whether he could effectively survive and manage racial stress with adequate resources. After spending several days in jail for asserting himself with the police, he reasoned that he did not have the ability or resources to manage the DRE to which he was exposed in his repeated contact with the police. Thus, Tyquan’s coping process was inhibited by a lack of racial coping self-efficacy. As a result, he chose to remain at home and disengage from contact with his friends. This avoidant racial coping strategy prevented him from enjoying normative adolescent behaviors. However, after Tyquan told his teacher and mentor, Drew, about his DRE, Drew likewise shared what he was subjected to in his own police experiences. Drew then provided Tyquan with a checklist of questions he had developed over time, serving as an important socialization tool for Tyquan which helped him to develop critical skills that he could use to navigate future experiences with the police. The practice of such skills in the development of RS competency also led to greater processing of emotions between Drew and Tyquan, as they cried after indicating how fearful and painful (i.e., traumatic) these encounters were for them. Tyquan indicated that his self-efficacy was enhanced, and he became able to reappraise and resolve his racial stress after he spoke to Drew and other providers while learning about legal and statistical information regarding stop-and-frisk practices. Finally, Tyquan saw improved long-term behavioral, cognitive, emotional, and social outcomes that were related to the ways in which Drew and other providers effectively socialized and efficaciously supported him to cope with DREs.

As illustrated through Tyquan’s experience, and as is evident in the RECAST model, RS operates as a moderator of racial stress, efficacy, and coping in the intermediate process to predict well-being outcomes. To cope with DREs, youth, parents, and other providers must first believe they can engage in stressful encounters through the execution of adaptive and literate racial coping skills. But literacy requires knowledge and action – and acting on one’s beliefs and knowledge requires skills, confidence, and practice (e.g., Avery et al., 2009). To gain skills, enhance confidence, and engage in intentional practice to address race-based traumatic stress and its symptomatic sequelae, therapeutic services and strategies for parents, youth, and the family system should continue to serve a critical role in the facilitation of healing processes for such stressful encounters.

Clinical Implications of Racial Socialization as a Practice for Healing

As a cognitive–behavioral intervention process, emotional regulation and processing of DREs can reduce anxiety, promote self-efficacy, and promote racial coping and agency for competent actions and reactions (e.g., Katsikitis, Bignell, Rooskov, Elms, & Davidson, 2013). Thus, a major implication for the threat appraisal role of RS is the potential benefit of cognitive restructuring. We expect that RECAST will predict how well African American youth can critically and consciously reappraise and resolve racial conflicts by facing and challenging the habitus of expendable Black humanity. Increased self-efficacy can help youth and parents to engage racial stress as a modifiable and problem-solving reality for systemic change, rather than a barrier that is insurmountable, through supportive dyadic coping.

Competence is developed through the practice and utility of contextually and problem-specific behavioral, cognitive, emotional, and social skills (e.g., Markus, Thomas, & Allpress, 2005). Although skills involving mindfulness and discernment of contextual conflict and regulation of emotions are teachable through practice and transferrable to a variety of coping contexts and demands (Hays & Iwamasa, 2006), RS themes have rarely been used to frame the development of these skills for youth to resolve racial encounters (Stevenson, 2003). Beyond the contribution of enhanced RS processes to the psychosocial, emotional, physical, and academic outcomes of youth, the need to reduce race-based traumatic stress in parents is often overlooked. As an example, while parents navigate the stress associated with DREs, negative affect may emerge that makes difficult the goal of reappraising an encounter as manageable (Coard & Sellers, 2005). It is interesting that negative RS communication may relieve stress in a manner similar to that of more positive RS (e.g., cultural pride): both forms of RS, in their own way, provide avenues for resolution of the conflict. However, negative RS communication comes at a hefty price for both parents and youth. The challenge lies in reframing the narrative: being Black itself is not the problem; rather, it is the effect of systematic and repeated exposure to negative racialized experiences that come from being of African descent in America (Carter & Forsyth, 2009). Presumably, such a shift to purposeful and mindful RS may relieve parents of their own emotional and psychological consequences from race-based traumatic stress. As such, there is a need for interventions to situate RS as a modifiable mechanism by which families of color can increase in efficacy and coping abilities to heal from stressful quotidian and cumulative DREs.

Although this article endeavors to clearly describe the tenets of a unifying and novel theory, there is also great need for empirical evidence that supports this model for applied purposes. The Engaging, Managing, and Bonding through Race (EMBRace; Anderson & Stevenson, 2016) intervention was developed from RECAST (Anderson, McKenny, & Stevenson, in press) and shows promise in advancing coping processes for parents, children, and the family unit (see Anderson, Jones, Navarro, McKenny, & Stevenson, 2018; Anderson, McKenny, Mitchell, Koku, & Stevenson, 2018). Other interventions with RS as a component (e.g., Black Parenting Strengths and Strategies: Coard et al., 2007; Preventing Long-term Anger and Aggression in Youth: Stevenson, 2003) can also benefit from the theoretical advancements brought forth from RECAST as they strive to improve parenting practices and child well-being.

Conclusion

Because research on youth development continues to lack an appreciation for the unique psychological conditions that racial experiences propel upon youth ecologies, a new RS theory must grapple with racial stress as historically traumatic, intergenerational, and pervasive in the daily fabric of family life (Carter, 2007; DeGruy-Leary, 2004). RECAST posits that an enhancement to the traditional legacy approach to RS (e.g., procedural, static) would require understanding, self-efficacy, and coping skills to more accurately read, recast, and resolve DREs through racial literacy (e.g., comprehension, transmission; Stevenson, 2014). RECAST and its practical application through clinical intervention (i.e., EMBRace) pushes the field toward the active utilization of RS to decrease race-based traumatic stress and improve psychological, health, academic, and identity-related long-term outcomes.

An implication of RECAST and intervention research that expects families to reach a level of competency in RS (a) delivery, (b) acquisition, and (c) implementation is that it symbolizes going from “The Talk” to “The Walk” during DREs. This approach also includes the development of measurement for trials of interventions infused with explicit, repeated, and practiced RS teaching targeted for specific racially stressful or uplifting social interactions to measure intervention components (e.g., fidelity) and RECAST elements (e.g., self-efficacy, coping; Stevenson, 2014, 2017). As such, this recommended model can also drive measurement and methodology better suited to assess the longitudinal dynamic of cognitive and behavioral processes inherent in the resolution of DREs through RS, including a corresponding observational and self-report assessment of RS competency designed for sensitivity to preto posttest change (see Anderson et al., 2018). Such a measure can provide supplemental information to the frequency of RS practices by further assessing skills and preparation.

Although RECAST attempts to more cohesively bridge frameworks and approaches for stress reduction, several important elements require more investigation. To be sure, the unique experiences of biracial and multiracial individuals will become increasingly salient in the coming generations. RS research on intersectionality beyond race and gender is sorely lacking, and given the abundance of evidence suggesting that gender is a factor in the socialization process and its reception (Cooper, Brown, Metzger, Clinton, & Guthrie, 2013; Hughes et al., 2006), interrogating the theory with parents and children of varying genders will also greatly contribute to RECAST processes. Furthermore, other child sociodemographic characteristics (e.g., age, phenotype) and temperament are strongly related to and inform parenting practices and thus would likewise need to be considered when theorizing RS practices with youth. Given that young children notice race throughout their development (e.g., Quintana, 1998), research would have to be conducted for RECAST to lend itself to various developmental periods. In the same way reading a novel would be challenging to a young child, reading a complicated racial situation would also prove difficult. As such, RS approaches for young children would not be absent; rather, would need to be modified to be understood within the scope of children’s developmental capacity (e.g., via hair-combing interactions; Lewis, 1999). Last, given that inferential evidence is limited, future large-scale research, particularly through intervention studies, will be crucial to support the authors’ claims. Indeed, future research aiming to test the theoretical postulates of RECAST would provide evidence for the model while also contributing to sorely needed clinical and community interventions for healing from racial stress and trauma.

Future Recommendations

Although limitations to this proposition are certain, this theorizing is meant to consolidate some aspects of research and attempts to position RS as reflected in verbal and nonverbal interactions that can relieve the racial stress, self-efficacy, and coping struggles of parents and children. However, to push the field of RS research in the future, clarity on the role of RS is just one step toward many in developing more sophisticated psychological and ecological measures and interventions. In addition to mindfully tracking how DREs are debilitating, future research might study how beneficial practiced responses can be in mitigating racial insult (e.g., debating, “comeback lines”; Stevenson, 2014). Given that racial stressors are arguably dissimilar from other stressors, extensions of this theory that consider how individuals make meaning of and cope with DREs during pivotal and specific developmental periods will be invaluable. Finally, although the focus of examples throughout the text has been on preparation for bias in the face of discrimination, this does not suggest that cultural socialization, for example, would not be a suitable strategy in addressing threat. This also does not imply that youth are naturally prepared for positive racial interactions without RS. The assertion cannot be made more strongly that if RS is provided without a core and primary commitment to affirming the cherished humanity of people of color, then it is undermining the competence necessary for youth to navigate current and future racialized environments.

#NoHashtag

In the text of the opening poem, the author details his mother’s helplessness in protecting him from a triggered police officer that would result in yet another tragic hashtag. In another poem, that author considers his nephew and reflects on one of the key elements of RECAST: literacy.

Don’t like the

fact that he learned to hide from the cops before he knew

how to read.

Angrier that his survival depends more on his ability

to deal with the “authorities”

than it does his own literacy.

Without explicit RS feedback on how to navigate DREs both internally and interpersonally, children and parents may be left to physiologically and emotionally restrictive reactions when they arise. With legacy RS, families are made aware of the complexity of race relations that go well or awry and may recommend procedural responses (e.g., “be polite”). But a literacy RS would expect more practicing of not only the procedural responses to make but, more important, the emotion regulation necessary to assertively address the DRE and count its emotional cost toward a psychologically healthy experience (e.g., appraise, grow in efficacy, cope, and achieve desired outcomes through heightened RS competency techniques). RECAST posits that, unlike the hopes and prayers of the mother in the opening poem, RS strategies must represent more than just a wishing well’s chance for survival and safe return home.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a Ford Foundation Postdoctoral Fellowship and Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Culture of Health Leaders Award. The authors are incredibly grateful for the editorial and supportive efforts of Shawn Jones, Jacqueline Mattis, and Monique McKenny. We are also thankful for the statistical clarity provided by Michael Rovine and Moin Sayed. Finally, the authors would like to acknowledge Jeannine Skinner for your loving support of this text – may you continue running through the heavens.

Biographies

Riana Elyse Anderson

Howard C. Stevenson

Contributor Information

Riana Elyse Anderson, University of Michigan.

Howard C. Stevenson, University of Pennsylvania

References

- Adam EK, Heissel JA, Zeiders KH, Richeson JA, Ross EC, Ehrlich KB, … Eccles JS (2015). Developmental histories of perceived racial discrimination and diurnal cortisol profiles in adulthood: A 20-year prospective study. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 62, 279–291. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.08.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Affleck G, & Tennen H (1996). Construing benefits from adversity: Adaptational significance and dispositional underpinnings. Journal of Personality, 64, 899–922. 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1996.tb00948.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association (APA). (2013). Discrimination: What it is, and how to cope. Retrieved June 1, 2017 from http://www.apa.org/helpcenter/discrimination.aspx

- Anderson RE, McKenny M, Mitchell A, Koku L, & Stevenson HC (2018). EMBRacing racial stress and trauma: Preliminary feasibility and coping outcomes of a racial socialization intervention. Journal of Black Psychology, 44, 25–46. 10.1177/0095798417732930 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson RE, Jones S, Anyiwo N, McKenny M, & Gaylord-Harden N (2018). What’s race got to do with it? The contribution of racial socialization to Black adolescent coping. Journal of Research on Adolescence. Advance online publication. 10.1111/jora.12440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson RE, Jones SCT, Navarro C, McKenny M, & Stevenson HC (2018). Addressing the mental health needs of Black youth and families: Solutions from a case in the EMBRace intervention. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15, 898. 10.3390/ijerph15050898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson RE, & Stevenson HC (2016). EMBRace training manual. Unpublished training manual, Racial Empowerment Collaborative, Graduate School of Education, University of Pennsylvania. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson RE, Jones SCT, & Stevenson HC (2018). Racial socialization competency: Quality over quantity. Manuscript submitted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson RE, McKenny M, & Stevenson HC (in press). EMBRace: Developing a Racial Socialization Intervention to Reduce Racial Stress and Enhance Racial Coping with Black Parents and Adolescents. Family Process. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avery DR, Richeson JA, Hebl MR, & Ambady N (2009). It does not have to be uncomfortable: The role of behavioral scripts in BlackWhite interracial interactions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94, 1382–1393. 10.1037/a0016208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York, NY: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Bentley K, Adams VN, & Author. (2009). Racial socialization: Roots, processes and outcomes. In Neville H, Tynes B, & Utsey S (Eds.), Handbook of African American psychology (pp. 255–267) Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop S, Lau M, Shapiro S, Carlson L, Anderson N, Carmody J,… Devins G (2004). Mindfulness: A proposed operational definition. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 11, 230–241. 10.1093/clipsy.bph077 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bodenmann G (1997). Dyadic coping: A systematic-transactional view of stress and coping among couples: Theory and empirical findings. European Review of Applied Psychology, 47, 137–140. [Google Scholar]

- Boykin AW, & Toms FD (1985). Black child socialization: A conceptual framework. In McAdoo H & McAdoo J (Eds.), Black children: Social, educational, and parental environments (pp. 33–52). Newbury Park, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Buehler S (2017). “Don’t want to get exposed”: Law’s violence and access to justice. Journal of Law and Social Policy, 26, 68–89. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne B, & Fielding-Barnsley R (1995). Evaluation of a program to teach phonemic awareness to young children: A 2and 3-year follow-up in a new preschool trial. Journal of Educational Psychology, 87, 488–503. 10.1037/0022-0663.87.3.488 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carter RT (2007). Racism and psychological and emotional injury: Recognizing and assessing race-based traumatic stress. Counseling Psychologist, 35, 13–105. 10.1177/0011000006292033 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carter RT, & Forsyth JM (2009). A guide to the forensic assessment of race-based traumatic stress reactions. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, 37, 28–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter R, Mazzula S, Victoria R, Vazquez R, Hall S, Smith S,… Williams B (2013). Initial development of the Race-Based Traumatic Stress Symptom Scale: Assessing the emotional impact of racism. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 5, 1–9. 10.1037/a0025911 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Caughy MOB, Nettles S, & Lima J (2011). Profiles of racial socialization among African American parents: Correlates, context, and outcome. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 20, 491–502. 10.1007/s10826-010-9416-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark R, Anderson NB, Clark VR, & Williams DR (1999). Racism as a stressor for African Americans. A biopsychosocial model. American Psychologist, 54, 805–816. 10.1037/0003-066X.54.10.805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coard S, Foy-Watson S, Zimmer C, & Wallace A (2007). Considering culturally relevant parenting practices in intervention development and adaptation: A randomized controlled trial of the Black Parenting Strengths and Strategies (BPSS) Program. Counseling Psychologist, 35, 797–820. 10.1177/0011000007304592 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coard S, & Sellers R (2005). African American families as a context for racial socialization. African American family life: Ecological and cultural diversity, 264–284. [Google Scholar]

- Comas-Díaz L (2016). Racial trauma recovery: A race-informed therapeutic approach to racial wounds. In Alvarez AN, Liang CTH, & Neville HA (Eds.), Cultural, racial, and ethnic psychology book series: The cost of racism for people of color: Contextualizing experiences of discrimination (pp. 249–272). 10.1037/14852-012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper SM, Brown C, Metzger I, Clinton Y, & Guthrie B (2013). Racial discrimination and African American adolescents’ adjustment: Gender variation in family and community social support, promotive and protective factors. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 22, 15–29. 10.1007/s10826-012-9608-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crouter AC, Baril ME, Davis K, & McHale SM (2008). Processes linking social class and racial socialization in African American dualearner families. Journal of Marriage and Family, 70, 1311–1325. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00568.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeGruy-Leary J (2004). Post traumatic slave syndrome: America’s legacy of enduring injury and healing (1st ed.). Milwaukie, OR: Upton Press. [Google Scholar]

- Derlan CL, & Umaña-Taylor AJ (2015). Brief report: Contextual predictors of African American adolescents’ ethnic-racial identity affirmation-belonging and resistance to peer pressure. Journal of Adolescence, 41, 1–6. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dressner J, & Martinez E (2012, June 12). The scars of stop-and-frisk. New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2012/06/12/opinion/the-scars-of-stop-and-frisk.html [Google Scholar]

- Fava GA, Rafanelli C, Cazzaro M, Conti S, & Grandi S (1998). Well-being therapy: A novel psychotherapeutic approach for residual symptoms of affective disorders. Psychological Medicine, 28, 475–480. 10.1017/S0033291797006363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer AR, & Shaw CM (1999). African Americans’ mental health and perceptions of racist discrimination: The moderating effects of racial socialization experiences and self-esteem. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 46, 395–407. 10.1037/0022-0167.46.3.395 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S (2013). Stress: Appraisal and coping. In Gellman MD & Turner JR (Eds.), Encyclopedia of behavioral medicine (2nd ed., pp. 1913–1915). 10.1007/978-1-4419-1005-9_215 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S, & Lazarus RS (1980). An analysis of coping in a middleaged community sample. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 21, 219–239. 10.2307/2136617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S, & Moskowitz JT (2000). Positive affect and the other side of coping. American Psychologist, 55, 647–654. 10.1037/0003-066X.55.6.647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland EL, Gaylord SA, & Fredrickson BL (2011). Positive reappraisal mediates the stress-reductive effects of mindfulness: An upward spiral process. Mindfulness, 2, 59–67. 10.1007/s12671-011-0043-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gudykunst W (1995). The uncertainty reduction and anxiety-uncertainty reduction theories of Berger and Gudykunst. In Cushman DP & Kovacic B (Eds.), Watershed research traditions in human communication theory (pp. 67–100). Albany, NY: SUNY Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gudykunst WB (2005). An anxiety/uncertainty management (AUM) theory of strangers’ intercultural adjustment. In Gudykunst WB (Ed.), Theorizing about intercultural communication (pp. 419–457). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Gudykunst WB, & Shapiro RB (1996). Communication in everyday interpersonal and intergroup encounters. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 20, 19– 45. 10.1016/0147-1767(96)00037-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hamm J, & Coleman H (2001). African American and White adolescents’ strategies for managing cultural diversity in predominantly White high schools. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 30, 281–303. 10.1023/A:1010488027628 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harrell SP (2000). A multidimensional conceptualization of racism-related stress: Implications for the well-being of people of color. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 70, 42–57. 10.1037/h0087722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris-Britt A, Valrie CR, Kurtz-Costes B, & Rowley SJ (2007). Perceived racial discrimination and self-esteem in African American youth: Racial socialization as a protective factor. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 17, 669–682. 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2007.00540.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays PA, & Iwamasa GY (Eds.). (2006). Culturally responsive cognitive-behavioral therapy: Assessment, practice, and supervision. 10.1037/11433-000 [DOI]

- Helms JE, Nicolas G, & Green CE (2012). Racism and ethnoviolence as trauma: Enhancing professional and research training. Traumatology, 18, 65–74. 10.1177/1534765610396728 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoggard LS, Byrd CM, & Sellers RM (2012). Comparison of African American college students’ coping with racially and nonracially stressful events. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 18, 329–339. 10.1037/a0029437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, & Chen L (1999). The nature of parents’ race-related communications to children: A developmental perspective. In Balter L & Tamis-LeMonda CS (Eds.), Child psychology: A handbook of contemporary issues (pp. 467–490). New York, NY: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, & Johnson D (2001). Correlates in children’s experiences of parents’ racial socialization behaviors. Journal of Marriage and Family, 63, 981–995. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.00981.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Rodriguez J, Smith EP, Johnson DJ, Stevenson HC, & Spicer P (2006). Parents’ ethnic-racial socialization practices: A review of research and directions for future study. Developmental Psychology, 42, 747–770. 10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Witherspoon D, Rivas-Drake D, & West-Bey N (2009). Received ethnic-racial socialization messages and youths’ academic and behavioral outcomes: Examining the mediating role of ethnic identity and self-esteem. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 15, 112–124. 10.1037/a0015509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huynh VW, & Fuligni AJ (2008). Ethnic socialization and the academic adjustment of adolescents from Mexican, Chinese, and European backgrounds. Developmental Psychology, 44, 1202–1208. 10.1037/0012-1649.44.4.1202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jernigan MM, & Daniel JH (2011). Racial trauma in the lives of Black children and adolescents: Challenges and clinical implications. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 4, 123–141. 10.1080/19361521.2011.574678 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson J (2013). Cuz he’s Black. Retrieved October 1, 2017, from https://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/black-poet-explains-painful-reality-of-police-violence-to-his-4-year-old-nephew_us_5644cb3fe4b06037734803cd

- Johnson J (2016). [Untitled poem]. Retrieved March 31, 2016, from https://www.instagram.com/p/BDm-Peojlb6/?taken-by[H11005]javonism

- Katsikitis M, Bignell K, Rooskov N, Elms L, & Davidson GR (2013). The family strengthening program: Influences on parental mood, parental sense of competence and family functioning. Advances in Mental Health, 11, 143–151. 10.5172/jamh.2013.11.2.143 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kliewer W, Fearnow MD, & Miller PA (1996). Coping socialization in middle childhood: Tests of maternal and paternal influences. Child Development, 67, 2339–2357. 10.2307/1131627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, & Folkman S (1984). Coping and adaptation. In Gentry WD (Ed.), The handbook of behavioral medicine (pp. 282–325). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lesane-Brown CL (2006). A review of race socialization within Black families. Developmental Review, 26, 400–426. 10.1016/j.dr.2006.02.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis ML (1999). Hair combing interactions: A new paradigm for research with African-American mothers. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 69, 504–514. 10.1037/h0080398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Major B, Kaiser CR, O’Brien LT, & McCoy SK (2007). Perceived discrimination as worldview threat or worldview confirmation: Implications for self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92, 1068–1086. 10.1037/0022-3514.92.6.1068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markus L, Thomas HC, & Allpress K (2005). Confounded by competencies? An evaluation of the evolution and use of competency models. New Zealand Journal of Psychology, 34, 117–126. [Google Scholar]

- McGill RK, Hughes D, Alicea S, & Way N (2012). Academic adjustment across middle school: The role of public regard and parenting. Developmental Psychology, 48, 1003–1018. 10.1037/a0026006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murry VM, Berkel C, Brody GH, Miller SJ, & Chen Y-F (2009). Linking parental socialization to interpersonal protective processes, academic self-presentation, and expectations among rural African American youth. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 15, 1–10. 10.1037/a0013180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neblett E Jr., Philip C, Cogburn C, & Sellers R (2006). African American adolescents’ discrimination experiences and academic achievement: Racial socialization as a cultural compensatory and protective factor. Journal of Black Psychology, 32, 199–218. 10.1177/0095798406287072 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pachter LM, Bernstein BA, Szalacha LA, & García Coll C (2010). Perceived racism and discrimination in children and youths: An exploratory study. Health & Social Work, 35, 61–69. 10.1093/hsw/35.1.61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisterman S, Firestone P, McGrath P, Goodman JT, Webster I, Mallory R, & Coffin B (1992). The effects of parent training on parenting stress and sense of competence. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, 24, 41–58. 10.1037/h0078699 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Provencher HL (2007). Role of psychological factors in studying recovery from a transactional stress-coping approach: Implications for mental health nursing practices. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 16, 188–197. 10.1111/j.1447-0349.2007.00466.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quintana SM (1998). Children’s developmental understanding of ethnicity and race. Applied & Preventive Psychology, 7, 27–45. 10.1016/S0962-1849(98)80020-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds JE, & Gonzales-Backen MA (2017). Ethnic-racial socialization and the mental health of African Americans: A critical review. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 9, 182–200. 10.1111/jftr.12192 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Richeson JA, & Trawalter S (2005). Why do interracial interactions impair executive function? A resource depletion account. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88, 934–947. 10.1037/0022-3514.88.6.934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez J, McKay MM, & Bannon WM Jr. (2008). The role of racial socialization in relation to parenting practices and youth behavior: An exploratory analysis. Social Work in Mental Health, 6, 30–54. 10.1080/15332980802032409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer PJ, Major B, Casad BJ, Townsend SS, & Mendes WB (2012). Discrimination and the stress response: Psychological and physiological consequences of anticipating prejudice in interethnic interactions. American Journal of Public Health, 102, 1020–1026. 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzer R, & Renner B (2000). Social-cognitive predictors of health behavior: Action self-efficacy and coping self-efficacy. Health Psychology, 19, 487–495. 10.1037/0278-6133.19.5.487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott LD Jr. (2003). The relation of racial identity and racial socialization to coping with discrimination among African American adolescents. Journal of Black Studies, 33, 520–538. 10.1177/0021934702250035 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seol KO, Yoo HC, Lee RM, Park JE, & Kyeong Y (2016). Racial and ethnic socialization as moderators of racial discrimination and school adjustment of adopted and nonadopted Korean American adolescents. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 63, 294–306. 10.1037/cou0000120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skiba RJ, & Williams NT (2014). Are Black kids worse? Myths and facts about racial differences in behavior. Bloomington: The Equity Project at Indiana University. [Google Scholar]

- Soto JA, Dawson-Andoh NA, & BeLue R (2011). The relationship between perceived discrimination and generalized anxiety disorder among African Americans, Afro Caribbeans, and non-Hispanic Whites. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 25, 258–265. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.09.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southern Poverty Law Center. (2016, November 28). The Trump effect: The impact of the 2016 presidential election on our nation’s schools. Retrieved from https://www.splcenter.org/20161128/trump-effect-impact-2016-presidential-election-our-nations-schools

- Spencer MB, Dupree D, & Hartmann T (1997). A phenomenological variant of ecological systems theory (PVEST): A self-organization perspective in context. Development and Psychopathology, 9, 817–833. 10.1017/S0954579497001454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson HC (2003). Playing with anger: Teaching coping skills to African American boys through athletics and culture. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group. [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson HC (2014). Promoting racial literacy in schools: Differences that make a difference. New York, NY: Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson HC (2017). Dueling narratives: Racial socialization and literacy as triggers for re-humanizing African American boys, young men and their families. In Burton LM, Burton D, McHale SM, King V, & Van Hook J (Eds.), National Symposium on Family Issues: Vol 7. Boys and men in African American families (pp. 55–84). 10.1007/978-3-319-43847-4_5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson HC, & Arrington E (2009). Racial/ethnic socialization mediates perceived racism and the racial identity of African American adolescents. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 15, 125–136. 10.1037/a0015500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson HC, Davis G, & Abdul-Kabir S (2001). Stickin’ to, watchin’ over, and gettin’ with: An African American parent’s guide to discipline. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Terrell F, Miller AR, Foster K, & Watkins CE Jr. (2006). Racial discrimination-induced anger and alcohol use among Black adolescents. Adolescence, 41, 485–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas A, & Blackmon S (2015). The influence of the Trayvon Martin shooting on racial socialization practices of African American parents. Journal of Black Psychology, 41, 75–89. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas DE, Coard SI, Stevenson HC, Bentley K, & Zamel P (2009). Racial and emotional factors predicting teachers’ perceptions of classroom behavioral maladjustment for urban African American male youth. Psychology in the Schools, 46, 184–196. [Google Scholar]

- Thornhill T (2016). Resistance and assent: How racial socialization shapes Black students’ experience learning African American history in high school. Urban Education, 51, 1126–1151. [Google Scholar]

- Tynes B, Giang M, Williams D, & Thompson G (2008). Online racial discrimination and psychological adjustment among adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 43, 565–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M, & Hughley J (2012). Parental racial socialization as a moderator of the effects of racial discrimination on educational success among African American adolescents. Child Development, 83, 1716–1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisz JR (1986). Contingency and control beliefs as predictors of psychotherapy outcomes among children and adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 54, 789–795. 10.1037/0022-006X.54.6.789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White-Johnson R, Ford K, & Sellers R (2010). Parental racial socialization profiles: Association with demographic factors, racial discrimination, childhood socialization, and racial identity. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 16, 237–247. 10.1037/a0016111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, & Leavell J (2012). The social context of cardiovascular disease: Challenges and opportunities for the Jackson Heart Study. Ethnicity & Disease, 22, 1–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, & Medlock M (2017). Health effects of dramatic societal events—Ramifications of the recent presidential election. New England Journal of Medicine, 376, 2295–2299. 10.1056/NEJMms1702111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods-Giscombé CL, & Black AR (2010). Mind-body interventions to reduce risk for health disparities related to stress and strength among African American women: The potential of mindfulness-based stress reduction, loving-kindness, and the NTU therapeutic framework. Complementary Health Practice Review, 15, 115–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worrell F, Vandiver B, Schaefer B, Cross W Jr., & Fhagen-Smith P (2006). Generalizing Nigrescence profiles: Cluster analyses of Cross Racial Identity Scale (CRIS) scores in three independent samples. Counseling Psychologist, 34, 519–547. [Google Scholar]

- Yasui M (2015). A review of the empirical assessment of processes in ethnic-racial socialization: Examining methodological advances and future areas of development. Developmental Review, 37, 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman M, & Gagne M (2003). The COPE revised: Proposing a 5-factor model of coping strategies. Journal of Research in Personality, 37, 169–204. [Google Scholar]