Abstract

Background:

Risk for suicide is growing among certain groups of Black Americans, yet the topic remains understudied. Discrimination appears to increase risk for suicidal thoughts and behaviors, but the evidence has been mixed for Black Americans. This study aimed to examine the association between major discriminatory events and suicidal thoughts and behaviors among Black American adults.

Methods:

We drew data from the National Survey of American Life, a representative sample of Black Americans, and used multivariable logistic regression to examine the associations between nine major discriminatory events and suicidal thoughts and behaviors (ideation, plan, attempt), adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics and psychiatric disorders.

Results:

We found that some major discriminatory events increased odds of reporting suicidal thoughts and behaviors, while others did not. Further, findings suggest the mediating role of psychiatric disorders.

Limitations:

The study drew from cross-sectional data and did not allow for causal inferences.

Conclusions:

Major discriminatory events have important implications for clinical practice, as well as diagnostic criteria when considering race-related stressors as a precipitator of suicidal thoughts and behaviors.

Keywords: Suicide, Discrimination, Suicidal ideation, Black Americans, African Americans

1. Introduction

In the United States, approximately 7.5% of Black Americans have had suicidal ideation and 2.7% have attempted suicide at some point in life (Joe et al., 2006). Generally, suicide is a public health concern (Control and Prevention, 2002; Joe et al., 2006), with statistics showing that Whites (specifically males) have the highest rate of suicide death out of all racial groups (Control and Prevention, 2002). However, this gap is beginning to narrow (Day-Vines, 2007), and suicide mortality continues to disproportionately impact certain racial and ethnic minority groups (Al-Mateen and Rogers, 2018) who are under-researched and have disproportionately less access to mental health resources (Ojeda and McGuire, 2006; Sentell et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2005). It is becoming increasingly important to understand the social risk factors that contribute to suicidal thoughts and behaviors among Black Americans (e.g. Walker, 2007; Walker et al., 2005). One social risk factor of interest is discrimination, which is defined as the unjust or prejudicial treatment of individuals on the basis of race, age, sex, or another socially defined characteristic (see Dovidio and Gaertner, 1986). Black Americans report more discriminatory experiences than their White counterparts (Lee et al., 2019). Discrimination can alter the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, which has been associated with numerous health problems (Jackson et al., 2010; Jackson and Knight, 2006); a large body of literature has shown that these discriminatory experiences can lead to adverse health effects (Pascoe and Smart Richman, 2009), mental health problems (Brown, 2003; Landrine and Klonoff, 1996; Mickelson and Williams, 1999; Oh et al., 2016; Williams et al., 1997), and suicidal thoughts and behaviors (Castle et al., 2011; Cheng et al., 2010; Gomez et al., 2011).

However, the literature has not been entirely consistent when examining discrimination and suicidal thoughts and behaviors for Black Americans. Gomez et al. (2011) studied emerging adults and found that racial discrimination was only significantly associated with suicide attempts among Latino Americans and White Americans, but not Black Americans. Similarly, Castle et al. (2011) found perceived discrimination was not associated with suicidal ideation or attempts. Gattis and Larson (2016) studied a sample of Black youth (aged 16–26, mostly homeless, nearly half of the sample non-heterosexual) and showed that racial discrimination was associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms, but not suicidal ideation, plan, or attempt. Arshanapally et al. (2018) found that among African American adolescents and young adults, discrimination increased the odds for any suicidal ideation, plan, or attempt after adjusting for psychiatric disorders; however, associations were no longer statistically significant after adjusting for maternal experiences of racial discrimination, depression, and problem drinking, implicating other social determinants and (epi)genetic factors. Walker et al. (2017) used longitudinal data and found that among African American youth, perceived racial discrimination was significantly associated with subsequent death ideation (thinking about death, including suicide). Likewise, Assari et al. (2017) found that among African American and Caribbean Black youth, perceived discrimination was associated with higher odds of suicidal ideation.

The inconsistency of findings may partly be due to the fact that prior studies did not account for various forms of discrimination, which is a multi-faceted construct that impacts health through multiple and complex pathways. The stress literature suggests that there are two different kinds of stress: one is a minor chronic type that can be characterized as daily hassles, while the other is a major type that can be characterized as events requiring significant readjustment (see DeLongis et al., 1982; Kanner et al., 1981). Along these lines, discrimination can be understood as everyday discrimination and major discriminatory events. Recently, Oh et al. (2019) found that everyday discrimination increased risk for suicidal thoughts and behaviors among racial and ethnic minorities; however, to our knowledge, no studies have examined the associations between specific major discriminatory events and suicidal thoughts and behaviors among Black American adults. Moreover, the aforementioned studies were primarily conducted with youth and young adults and did not uniformly adjust for DSM psychiatric disorders using strong measures. In this study, we drew data from a representative sample of Black Americans to analyze the associations between several major discriminatory events and suicide outcomes.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Sample and procedures

This paper analyzed data from the National Survey of American Life (NSAL; Jackson et al., 2004), a national household probability sample of 5191 Black Americans (3570 African Americans and 1621 Caribbean Black Americans) that was conducted between the years 2001 and 2003 using the World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview (WHO CIDI; Kessler and Üstün, 2004). The study population included non-institutionalized adults over the age of 18 who were selected through a multistage probability sampling strategy to achieve nationally representative samples of African Americans living in the United States (Heeringa et al., 2004). Special supplements were used to oversample from census block groups with high-density of individuals of Caribbean national origin. The response rate for the overall NSAL sample was 72.3% (70.7% for African American and 77.7% for Caribbean Blacks). Details on the sampling strategy and interview procedures have been described in depth elsewhere (see Pennell et al., 2004). The survey investigators provided survey weighting, stratification, and cluster sampling variables to adjust for errors inherent in complex sampling techniques used in the NSAL.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Lifetime suicidal thoughts/behaviors (Dependent variable)

In 81.4% of the sample, suicidal thoughts/behaviors was assessed through a written self-report module for respondents literate in English, which helps mitigate the influence of social desirability bias. Another 17.4% of the sample were asked the suicidal thoughts/behaviors questions in face-to-face interviews in the respondents’ primary language. Prior studies have found that prevalence of suicidal thoughts and behaviors did not vary depending on self-report module vs. face-to-face interviews (DeVylder et al., 2015). In keeping with prior studies that used these data, the responses were collapsed into three separate variables: suicidal ideation, suicide plans, and suicide attempts. Respondents reported (yes/no) to whether they had ever seriously thought about suicide; if yes, respondents were then asked (yes/no) if they had ever made a plan, and if they had ever made an attempt.

2.2.2. Major discriminatory events

Discrimination was assessed using a questionnaire adapted from the Lifetime Discrimination sub scale of the Detroit Area Study Discrimination Questionnaire (DAS-DQ; Taylor et al., 2004), and had a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.64. Respondents indicated whether or not they had ever experienced nine specific major discriminatory events in their lifetimes (see Table 1). These events were non-specific, and did not specifically refer to racial discrimination. We also created a continuous variable that counted the number of discriminatory events (ranging from 0 to 9).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of major discriminatory events and lifetime suicidality.

| Total % (SE) | N | Missing N | Suicidal ideation Yes | No | χ2 | Suicide plan Yes | No | χ2 | Suicide attempt Yes | No | χ2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unfairly fired | 24.89 (0.86) | 1102 | 79 | 40.91 (2.39) | 22.92 (0.92) | 52.82 *** | 43.20 (3.99) | 24.20 (0.87) | 26.17 *** | 39.39 (4.77) | 24.35 (0.81) | 13.22 *** |

| Not hired | 22.54 (1.02) | 1043 | 187 | 26.07 (2.48) | 22.06 (1.14) | 2.15 | 24.41 (3.77) | 22.42 (1.08) | 0.26 | 22.10 (4.21) | 22.52 (1.08) | 0.01 |

| Denied promotion | 20.39 (0.92) | 914 | 113 | 24.33 (2.49) | 20.05 (0.95) | 3.15 | 21.83 (4.09) | 20.47 (0.96) | 0.12 | 24.32 (4.55) | 20.37 (0.91) | 0.90 |

| Police abuse | 28.17 (1.19) | 1185 | 50 | 36.56 (2.97) | 27.08 (1.14) | 12.57 *** | 41.33 (4.65) | 27.61 (1.14) | 10.70 ** | 41.71 (4.89) | 27.59 (1.14) | 10.60 ** |

| Discouraged from education | 10.64 (0.87) | 511 | 56 | 15.14 (1.82) | 9.97 (0.86) | 9.05 ** | 21.62 (2.96) | 10.10 (0.82) | 24.94 *** | 23.00 (3.68) | 10.03 (0.83) | 20.57 *** |

| Neighborhood exclusion | 8.99 (0.72) | 416 | 72 | 14.10 (2.05) | 8.36 (0.70) | 12.19 *** | 14.31 (3.81) | 8.79 (0.68) | 3.63 | 15.02 (3.38) | 8.75 (0.74) | 4.98 * |

| Neighbor harassment | 8.03 (0.51) | 358 | 52 | 12.76 (1.69) | 7.64 (0.55) | 13.07 *** | 16.32 (4.24) | 7.88 (0.56) | 7.16 ** | 17.88 (3.61) | 7.81 (0.52) | 15.96 *** |

| Denied loan | 10.22 (0.62) | 442 | 222 | 11.32 (1.87) | 10.52 (0.74) | 0.34 | 12.33 (3.34) | 10.52 (0.71) | 0.40 | 7.98 (2.58) | 10.71 (0.70) | 0.54 |

| Bad service | 13.14 (0.85) | 574 | 128 | 16.53 (2.38) | 12.97 (0.91) | 2.41 | 15.71 (3.98) | 13.28 (0.81) | 0.46 | 15.74 (3.55) | 13.28 (0.84) | 0.64 |

Weighted percentages (standard errors).

Rao-Scott chi-square test statistic presented.

p < 0.05,.

p < 0.01,.

Missing: Don’t Know/Refused to answer.

Missing: Don’t Know/Refused to answer

2.2.3. Sociodemographic characteristics (Covariates)

In accordance with prior literature, sociodemographic covariates that have been known to be related to both discrimination and suicidal thoughts and behaviors include: age, sex (male, female), ethnicity (African American, Caribbean Black), income (poor, near poor, non-poor), education (less than high school, high school graduate, some college, college graduate and beyond) (Garrison, 1992; Krieger, 2000; Mościcki, 1999).

2.2.4. Psychiatric disorders (Covariates)

Lifetime psychiatric disorders were based on the Word Mental Health Composite International Diagnostic Interview (Kessler and Üstün, 2004), a fully structured lay interview to screen for diagnoses according to DSM-IV criteria. Lifetime psychiatric disorders were based on DSM-IV criteria, and included: (1) mood disorders (dysthymia, depressive episode, major depressive disorder), (2) anxiety disorders (agoraphobia with and without panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, panic attacks, panic disorder, post-traumatic stress, social phobia), (3) substance use disorders (drug abuse and dependence), and (4) alcohol use disorders (alcohol abuse and dependence). These were coded as four separate dummy variables.

2.3. Main analyses

Descriptive statistics were calculated for the overall sample, and then stratified by lifetime suicidal thoughts and behaviors. Separate multivariable logistic regression models were used to examine each individual discriminatory event and its relation to lifetime suicidal ideation, suicide plans, and suicide attempts, adjusting for socio-demographic confounders in the first block, and psychiatric disorders in the second block. Additional regression models examined the association between a continuous count of discriminatory events and suicide thoughts and behaviors. Due to small cell counts, lifetime measures of suicide were used instead of 12-month. Standard errors were estimated through design-based analyses that used the Taylor series linearization method to account for the complex multistage clustered design, with U.S. metropolitan statistical areas or counties as the primary sampling units. Sampling weights were used for all statistical analyses to account for individual-level sampling factors (i.e. non-response and unequal probabilities of selection). Individuals who reported ‘not applicable’ and ‘I don’t know’ on any one of the nine items were dropped from the analyses. Complete case analyses were used, and sample sizes for models were allowed to vary according to the data that were available. Effect sizes for all multivariable logistic regression models were presented as odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). For all analyses, the significance level was set at a = =0.05, two-tailed. All analyses were performed using STATA SE version 15.

3. Results

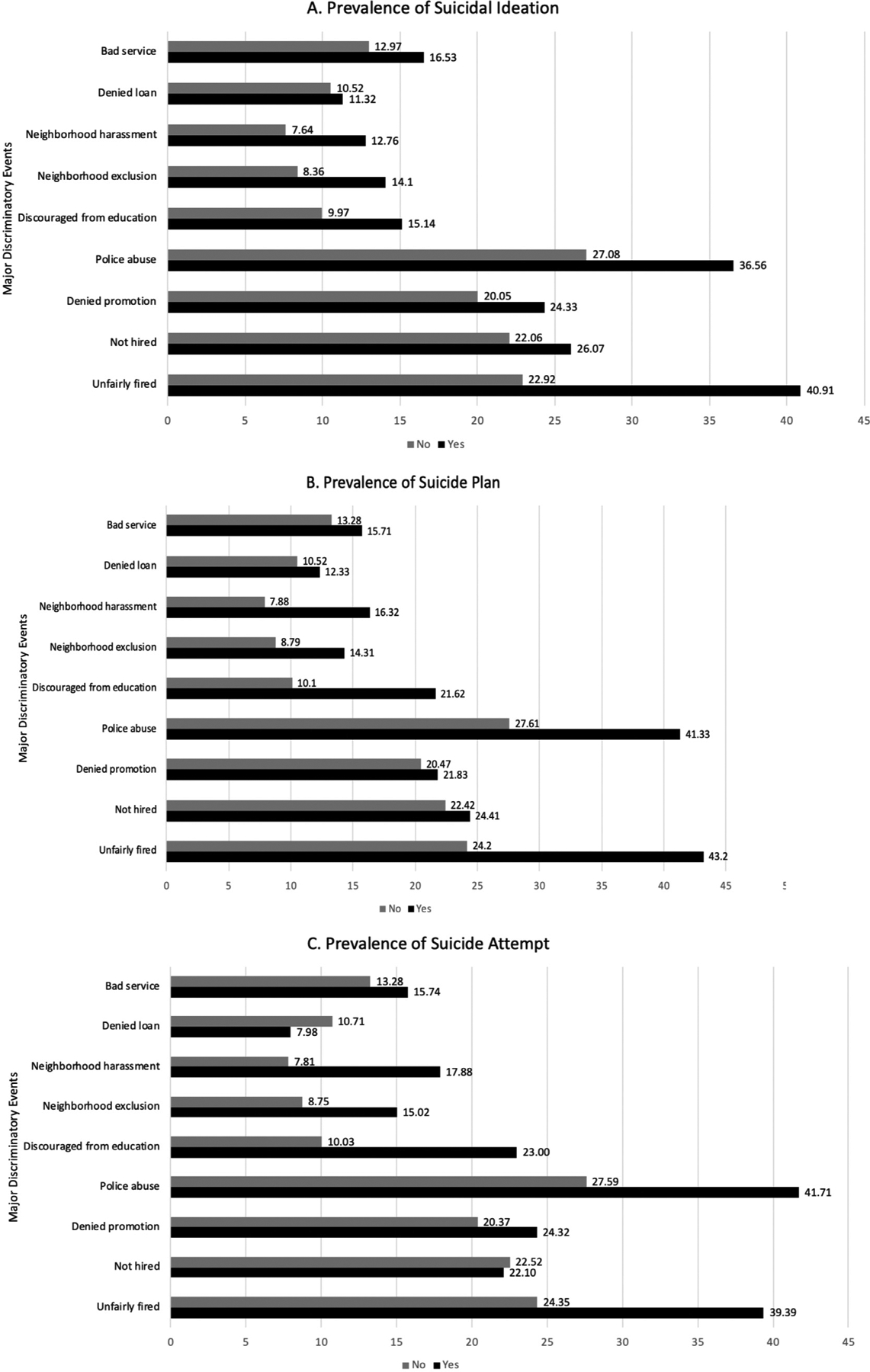

The prevalence of each of the nine major discriminatory events have been depicted in Table 1. The most common type of discrimination was police abuse (28.17%), while the least common type of discrimination was harassment from neighbors (8.03%). The prevalence of each discriminatory event stratified by suicidal thoughts and behaviors are presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Prevalence of lifetime suicidal ideation, suicide plan, and suicide attempt National Survey of American Life, 2002.

In models adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics, all major discriminatory events were associated with suicidal ideation with the exception of not being hired and being denied a loan Table 2. Being unfairly fired, police abuse, discouraged from education, being excluded from neighborhood, and neighborhood harassment were associated with suicide plan. Being unfairly fired, police abuse, being discouraged from pursuing education, being excluded from a neighborhood, and neighborhood harassment was associated with suicide attempt.

Table 2.

Multi-variable logistic regression models depicting association between major discriminatory events and lifetime suicidal thoughts and behaviors.

| Lifetime suicidal ideation | Lifetime suicide plan | Lifetime suicide attempt | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | I + II | I | I + II | I | I + II | |

| Major Discriminatory Events | ||||||

| Unfairly fired | 2.41 (1.89–3.07) *** | 1.83 (1.39–2.43) *** | 2.51 (1.78–3.56) *** | 1.82 (1.25–2.64) ** | 2.11 (1.44–3.09) *** | 1.41 (0.89–2.24) |

| Not hired | 1.36 (0.99–1.87) | 1.09 (0.78–1.52) | 1.27 (0.82–1.95) | 0.94 (0.60–1.47) | 1.06 (0.64–1.78) | 0.73 (0.40–1.30) |

| Denied promotion | 1.57 (1.13–2.18) ** | 1.26 (0.86–1.85) | 1.42 (0.79–2.55) | 1.07 (0.56–2.05) | 1.69 (0.99–2.89) | 1.25 (0.68–2.29) |

| Police abuse | 1.83 (1.40–2.38) *** | 1.34 (1.00–1.79) * | 2.60 (1.78–3.80) *** | 1.83 (1.26–2.66) ** | 2.53 (1.70–3.75) *** | 1.70 (1.09–2.67) * |

| Discouraged from education | 1.78 (1.28–2.48) ** | 1.29 (0.90–1.85) | 2.83 (1.90–4.22) *** | 2.01 (1.33–3.04) ** | 3.08 (1.92–4.96) *** | 2.28 (1.35–3.85) ** |

| Excluded from neighborhood | 1.93 (1.38–2.72) *** | 1.61 (1.11–2.34) * | 1.89 (1.05–3.40) * | 1.42 (0.71–2.83) | 1.98 (1.10–3.56) * | 1.47 (0.75–2.88) |

| Neighbor harassment | 1.74 (1.25–2.43) ** | 1.31 (0.90–1.90) | 2.20 (1.15–4.21) * | 1.53 (0.79–2.94) | 2.47 (1.49–4.12) ** | 1.75 (0.99–3.09) |

| Denied loan | 1.23 (0.79–1.92) | 1.11 (0.66–1.85) | 1.42 (0.70–2.88) | 1.22 (0.57–2.58) | 0.84 (0.39–1.79) | 0.72 (0.32–1.62) |

| Bad service | 1.59 (1.05–2.41) * | 1.20 (0.76–1.88) | 1.55 (0.82–2.93) | 1.09 (0.55–2.14) | 1.55 (0.89–2.70) | 1.11 (0.62–1.97) |

| Count of events (0–9) | 1.23 (1.15–1.32) *** | 1.12 (1.02–1.22) * | 1.30 (1.18–1.44) *** | 1.16 (1.03–1.32) * | 1.29 (1.15–1.44) *** | 1.14 (0.97–1.33) |

| N | 5810–5996 | 4878–4956 | 5810–5996 | 4878–4956 | 5810–5996 | 4878–4956 |

All discriminatory events were examined in separate models.

I. Adjusted for ethnicity, sex, age, education, income-to-poverty ratio.

II. Adjusted for lifetime substance use disorder, lifetime anxiety disorder, lifetime alcohol use disorder, lifetime mood disorder.

p < 0.05;.

p < 0.01,.

p < 0.001 (for the purposes of this analysis, p < 0.01 was considered statistically significant, while p < 0.05 was considered marginally significant).

In models adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics and psychiatric disorders, being unfairly fired, police abuse and being discouraged from moving into a neighborhood were associated with greater odds of reporting suicidal ideation. Being unfairly fired, police abuse, and being discouraged from pursuing education were associated with greater odds of reporting suicide plan. Police abuse and being discouraged from education were the only events associated with greater odds of making a suicide attempt.

As a count of events, major discriminatory events were associated with greater odds of reporting suicidal ideation in a dose-response fashion. The count of events was not associated with suicide attempt at a conventional level of statistical significance after controlling for psychiatric disorders; however, the point-estimate still suggests a 14% increase in the odds of suicide attempt.

4. Discussion

4.1. Main findings

The goal of our study was to determine whether major discriminatory events were related to suicidal thoughts and behaviors in Black American adults. The main finding is that certain major discriminatory events independently increased the odds of reporting lifetime suicidal thoughts and behaviors, while other events did not. This provides some evidence to suggest that not all major discriminatory events hold the same meaning or confer the same amount of stress toward various suicidal thoughts or behaviors. For example, in the fully adjusted models, being unfairly fired was associated with greater odds of reporting suicidal ideation and plan, but not attempt. Being excluded from a neighborhood was only predictive of suicidal ideation, but not suicide plans or attempts. The only major discriminatory event that came close to being predictive across all suicidal thoughts and behaviors was police abuse. The discriminatory events measure had a relatively low internal consistency, suggesting that each individual exposure may have not been capturing the same underlying construct and may explain the variability in associations between items. Despite this heterogeneity of effects across individual discriminatory exposures, the count of major discriminatory events increased the odds of reporting suicidal ideation and plans in a dose-response fashion, with a similar but non-significant pattern for suicide attempts. Overall, associations attenuated after adjusting for lifetime psychiatric disorders suggesting a partial mediation effect.

There have now been several studies linking police violence exposure to suicidal behavior, showing an extremely elevated prevalence of risk for suicide attempts among victims of sexual or physical police violence (DeVylder et al., 2018, 2017). Importantly, the present data replicate these findings in a nationally-representative sample. The odds ratio is notably smaller, however, likely reflecting the current study’s use of a more general indicator of police abuse that likely included non-violent incidents. Still, police violence has emerged as an important predictor of mental health problems (Oh et al., 2017), including suicidal thoughts and behaviors, and deserves more attention in public health research.

4.2. Putative mechanisms

There are numerous pathways by which discrimination may impact suicidal thoughts and behaviors. Our findings showed that the relation between discrimination and suicidal thoughts and behaviors attenuated after adjusting for psychiatric disorders, suggesting that mental illness may function as a putative mediator. However, the associations between discrimination and suicidal thoughts and behaviors remained statistically significant despite the adjustments for psychiatric disorder, implicating other explanatory mechanisms that were not examined in the current study, such as acculturative stress (Walker, 2007), family conflict (Compton et al., 2005; Gibbs, 1997; Stack and Wasserman, 1995), and religion (Chatters et al., 2011; Taylor et al., 2011). These factors may have roles in mediating or moderating the associations we found.

On a biological level, discrimination can trigger the stress-response system, activating the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis to release stress hormones that cause neuroinflammation. Repeated activation of the HPA axis can over time sensitize regions of the brain, making subsequent stress more impactful or more difficult to manage, resulting in mental and physical health problems such as depression and anxiety (Berk et al., 2013; Brundin et al., 2015; Raison et al., 2006) as well as alcohol and drug use. These mental health problems, in turn, can contribute to suicide risk (Borges et al., 2010, 2008).

The Interpersonal Psychological Theory of Suicide (IPTS; Van Orden et al., 2010) posits that feeling ostracized (i.e. thwarted belongingness) and thinking that one is a burden on others (Joiner et al., 2002) can give rise to suicidal thoughts. Moreover, repeated exposures to painful and fear-inducing experiences make one susceptible to suicidal behaviors. Our findings contribute to the IPTS literature by underscoring the role of discrimination as a factor that may create a sense of thwarted belongingness in workplaces, neighborhoods and communities, institutions, business establishments, public spaces, and the larger society. Additionally, discrimination may involve painful and fear-inducing experiences (Carter, 2007; Carter et al., 2005), increasing the risk for suicide attempts. The number of studies that apply the IPTS to African Americans is limited. Klibert et al. (2015) proposed a framework to understand suicide risk specifically for African Americans, highlighting the importance of interpersonal discord, feeling as though one’s culture is not acceptable, and low self-concept. Repeated experiences of major discriminatory events may operate through these mechanisms.

4.3. Potential Limitations

Our findings should be interpreted bearing in mind a number of potential limitations. First, the data were cross-sectional, which does not allow us to make any causal inferences. Second, this study was exploratory and did not examine several key mediators and moderators, which may help explain the variability in findings. As alluded to earlier, prior studies have identified important mediators, such as family relations (Compton et al., 2005; Gibbs, 1997; Stack and Wasserman, 1995), negative interactions and emotional support (Lincoln et al., 2012), as well as important moderators such as acculturative stress and ethnic identity (Cheref et al., 2016; Walker et al., 2008) and religiosity (Taylor et al., 2011; Walker et al., 2018, 2014). Third, the major discriminatory events captured the range of events in various life domains, but did not elicit frequency of events or associated levels of distress. It is possible that some events may be particularly bothersome to the individual while other events may be relatively meaningless. That being said, a strength of this study was that the major discriminatory events touched on discrimination in various domains at the institutional, organizational, and structural levels. Discrimination in these forms can be insidious and slowly erode health, hindering access to timely and high-quality healthcare treatment (Wong et al., 2014). This research contributes to the identification of mechanisms that underlie specific major discriminatory events and suicidal thoughts and behaviors, which can help formulate culturally-informed assessments and interventions to identify at-risk individuals and reduce suicide attempts among people of color.

5. Conclusions

Our study has critical implications for training health and mental health professionals to monitor and care for Black Americans at risk for suicide. Discrimination screenings can be administered in various community-based health care and social service settings in Black communities to identify those who endorse specific discriminatory items, referring them to suicide prevention programs that provide psycho-education and other resources. Individuals with history of experiencing police abuse or those who have ever been discouraged from pursuing education may be particularly vulnerable, and may benefit from community-driven programs to build resilience. On a final note, scholars, practitioners, and policy-makers must endeavor to eliminate discrimination to reduce suicide risk for Black Americans.

Footnotes

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Hans Oh: Writing - review & editing. Kyle Waldman: Writing - review & editing. Ai Koyanagi: Writing - review & editing. Riana Anderson: Writing - review & editing. Jordan DeVylder: Writing - review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None.

References

- Al-Mateen CS, Rogers KM, 2018. Suicide among African-American and other African-origin youth. Suicide Among Diverse Youth. Springer, pp. 31–49. [Google Scholar]

- Arshanapally S, Werner KB, Sartor CE, Bucholz KK, 2018. The association between racial discrimination and suicidality among African–American adolescents and young adults. Arch. Suicide Res 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assari S, Moghani Lankarani M, Caldwell CH, 2017. Discrimination increases suicidal ideation in black adolescents regardless of ethnicity and gender. Behav. Sci 7, 75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berk M, Williams LJ, Jacka FN, O’Neil A, Pasco JA, Moylan S, Allen NB, Stuart AL, Hayley AC, Byrne ML, 2013. So depression is an inflammatory disease, but where does the inflammation come from? BMC Med. 11, 200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges G, Angst J, Nock MK, Ruscio AM, Kessler RC, 2008. Risk factors for the incidence and persistence of suicide-related outcomes: a 10-year follow-up study using the National Comorbidity Surveys. J. Affect Disord 105, 25–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges G, Nock MK, Abad JMH, Hwang I, Sampson NA, Alonso J, Andrade LH, Angermeyer MC, Beautrais A, Bromet E, 2010. Twelve month prevalence of and risk factors for suicide attempts in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. J. Clin. Psychiatry 71, 1617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TN, 2003. Critical race theory speaks to the sociology of mental health: mental health problems produced by racial stratification. J. Health Soc. Behav 292–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brundin L, Erhardt S, Bryleva EY, Achtyes ED, Postolache TT, 2015. The role of inflammation in suicidal behaviour. Acta Psychiatr. Scand 132, 192–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter RT, 2007. Racism and psychological and emotional injury recognizing and assessing race-based traumatic stress. Couns. Psychol 35, 13–105. [Google Scholar]

- Carter RT, Forsyth JM, Mazzula SL, Williams B, 2005. Racial discrimination and race-based traumatic stress: An exploratory investigation. Handbook of Racial-Cultural Psychology And Counseling: Training And Practice. . 2. pp. 447–476. [Google Scholar]

- Castle K, Conner K, Kaukeinen K, Tu X, 2011. Perceived racism, discrimination, and acculturation in suicidal ideation and suicide attempts among black young adults. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav 41, 342–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatters LM, Taylor RJ, Lincoln KD, Nguyen A, Joe S, 2011. Church-based social support and suicidality among African Americans and Black Caribbeans. Arch. Suicide Res 15, 337–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng JKY, Fancher TL, Ratanasen M, Conner KR, Duberstein PR, Sue S, Takeuchi D, 2010. Lifetime suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in Asian Americans. Asian Am. J. Psychol 1, 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheref S, Talavera D, Walker RL, 2016. Perceived discrimination and suicide ideation: moderating roles of anxiety symptoms and ethnic identity among Asian American, African American, and Hispanic emerging adults. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton MT, Thompson NJ, Kaslow NJ, 2005. Social environment factors associated with suicide attempt among low-income African Americans: the protective role of family relationships and social support. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol 40, 175–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Control, C. for D., Prevention, 2002. Web-based injury statistics query and reporting system (WISQARS). www.cdc.gov/ncipc/wisqars.

- Day-Vines NL, 2007. The escalating incidence of suicide among African Americans: implications for counselors. J. Couns. Dev 85, 370–377. [Google Scholar]

- DeLongis A, Coyne JC, Dakof G, Folkman S, Lazarus RS, 1982. Relationship of daily hassles, uplifts, and major life events to health status. Health Psychol. 1, 119. [Google Scholar]

- DeVylder JE, Frey JJ, Cogburn CD, Wilcox HC, Sharpe TL, Oh HY, Nam B, Link BG, 2017. Elevated prevalence of suicide attempts among victims of police violence in the USA. J. Urban Health 94, 629–636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVylder JE, Jun H-J, Fedina L, Coleman D, Anglin D, Cogburn C, Link B, Barth RP, 2018. Association of exposure to police violence with prevalence of mental health symptoms among urban residents in the United States. JAMA Netw. Open 1, e184945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVylder JE, Lukens EP, Link BG, Lieberman JA, 2015. Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts among adults with psychotic experiences: data from the Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Surveys. JAMA Psychiatry 72, 219–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dovidio JF, Gaertner SL, 1986. Prejudice, Discrimination, and Racism. Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Garrison CZ, 1992. Demographic predictors of suicide.

- Gattis MN, Larson A, 2016. Perceived racial, sexual identity, and homeless status-related discrimination among Black adolescents and young adults experiencing homelessness: relations with depressive symptoms and suicidality. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 86, 79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs JT, 1997. 8 African-American suicide: a cultural paradox. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav 27, 68–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez J, Miranda R, Polanco L, 2011. Acculturative stress, perceived discrimination, and vulnerability to suicide attempts among emerging adults. J. Youth Adolesc 40, 1465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heeringa SG, Wagner J, Torres M, Duan N, Adams T, Berglund P, 2004. Sample designs and sampling methods for the Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Studies (CPES). Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res 13, 221–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson JS, Knight KM, 2006. Race and self-regulatory health behaviors: the role of the stress response and the HPA axis in physical and mental health disparities. Soc. Struct. Aging Self-Regul. Elder 189–239. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson JS, Knight KM, Rafferty JA, 2010. Race and unhealthy behaviors: chronic stress, the HPA axis, and physical and mental health disparities over the life course. Am. J. Public Health 100, 933–939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson JS, Torres M, Caldwell CH, Neighbors HW, Nesse RM, Taylor RJ, Trierweiler SJ, Williams DR, 2004. The National Survey of American Life: a study of racial, ethnic and cultural influences on mental disorders and mental health. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res 13, 196–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joe S, Baser RE, Breeden G, Neighbors HW, Jackson JS, 2006. Prevalence of and risk factors for lifetime suicide attempts among blacks in the United States. JAMA 296, 2112–2123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE, Pettit JW, Walker RL, Voelz ZR, Cruz J, Rudd MD, Lester D, 2002. Perceived burdensomeness and suicidality: two studies on the suicide notes of those attempting and those completing suicide. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol 21, 531–545. [Google Scholar]

- Kanner AD, Coyne JC, Schaefer C, Lazarus RS, 1981. Comparison of two modes of stress measurement: daily hassles and uplifts versus major life events. J. Behav. Med 4, 1–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Üstün TB, 2004. The world mental health (WMH) survey initiative version of the world health organization (WHO) composite international diagnostic interview (CIDI). Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res 13, 93–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klibert J, Barefoot KN, Langhinrichsen-Rohling J, Warren JC, Smalley KB, 2015. Cross-cultural and cognitive-affective models of suicide risk. J. Black Psychol 41, 272–295. [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N, 2000. Discrimination and health. Social Epidemiology Oxford University Press, Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Landrine H, Klonoff EA, 1996. The schedule of racist events: a measure of racial discrimination and a study of its negative physical and mental health consequences. J. Black Psychol 22, 144–168. [Google Scholar]

- Lee RT, Perez AD, Boykin CM, Mendoza-Denton R, 2019. On the prevalence of racial discrimination in the United States. PLoS One 14, e0210698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln KD, Taylor RJ, Chatters LM, Joe S, 2012. Suicide, negative interaction and emotional support among Black Americans. Soc. Psychiatr. Epidemiol 47, 1947–1958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mickelson KD, Williams DR, 1999. The prevalence, distribution, and mental health correlates of perceived discrimination in the United States. J. Health Soc. Behav 40, 208–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mościcki EK, 1999. Epidemiology of suicide. [PubMed]

- Oh H, Cogburn CD, Anglin D, Lukens E, DeVylder J, 2016. Major discriminatory events and risk for psychotic experiences among Black Americans. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh H, DeVylder J, Hunt G, 2017. Effect of Police Training and Accountability on the Mental Health of African American Adults. American Public Health Association. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh H, Stickley A, Koyanagi A, Yau R, DeVylder JE, 2019. Discrimination and suicidality among racial and ethnic minorities in the United States. J. Affect. Disord 245, 517–523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojeda VD, McGuire TG, 2006. Gender and racial/ethnic differences in use of out-patient mental health and substance use services by depressed adults. Psychiatr. Q 77, 211–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascoe EA, Smart Richman L, 2009. Perceived discrimination and health: a meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull 135, 531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennell B-E, Bowers A, Carr D, Chardoul S, Cheung G, Dinkelmann K, Gebler N, Hansen SE, Pennell S, Torres M, 2004. The development and implementation of the national comorbidity survey replication, the national survey of American life, and the national Latino and Asian American survey. Int. J Methods Psychiatr. Res 13, 241–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raison CL, Capuron L, Miller AH, 2006. Cytokines sing the blues: inflammation and the pathogenesis of depression. Trends Immunol. 27, 24–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sentell T, Shumway M, Snowden L, 2007. Access to mental health treatment by English language proficiency and race/ethnicity. J. Gen. Intern. Med 22, 289–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stack S, Wasserman I, 1995. The effect of marriage, family, and religious ties on African American suicide ideology. J. Marriage Fam 215–222. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ, Chatters LM, Joe S, 2011. Religious involvement and suicidal behavior among African Americans and Black Caribbeans. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis 199, 478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Cukrowicz KC, Braithwaite SR, Selby EA, Joiner TE Jr., 2010. The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychol. Rev 117, 575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker R, Francis D, Brody G, Simons R, Cutrona C, Gibbons F, 2017. A longitudinal study of racial discrimination and risk for death ideation in African American youth. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav 47, 86–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker RL, 2007. Acculturation and acculturative stress as indicators for suicide risk among African Americans. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 77, 386–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker RL, Salami T, Carter S, Flowers KC, 2018. Religious coping style and cultural worldview are associated with suicide ideation among African American adults. Arch. Suicide Res 22, 106–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker RL, Salami TK, Carter SE, Flowers K, 2014. Perceived racism and suicide ideation: mediating role of depression but moderating role of religiosity among African American adults. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav 44, 548–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker RL, Utsey SO, Bolden MA, Williams III O, 2005. Do sociocultural factors predict suicidality among persons of African descent living in the US? Arch. Suicide Res 9, 203–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker RL, Wingate LR, Obasi EM, Joiner TE Jr., 2008. An empirical investigation of acculturative stress and ethnic identity as moderators for depression and suicidal ideation in college students. Cult. Divers. Ethnic Minority Psychol 14, 75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang PS, Lane M, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Wells KB, Kessler RC, 2005. Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States: results from the national comorbidity survey replication. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 62, 629–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Yu Y, Jackson JS, Anderson NB, 1997. Racial differences in physical and mental health socio-economic status, stress and discrimination. J. Health Psychol 2, 335–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong YJ, Maffini CS, Shin M, 2014. The racial-cultural framework: a framework for addressing suicide-related outcomes in communities of color. Couns. Psychol 42, 13–54. [Google Scholar]