Abstract

Researchers have illustrated the deleterious psychological effects that racism and discrimination have exerted on Black Americans. The resulting racial stress and trauma (RST) from experiences with discrimination has been linked to negative wellness outcomes and trajectories for Black youth and families. Racial socialization (RS)—defined as the verbal and nonverbal messages that families use to communicate race to their children—can be a cultural strength and has been associated with positive outcomes in Black youth. Furthermore, the Racial Encounter Coping Appraisal and Socialization Theory (RECAST) encourages the frequent and competent use of RS between family members to cope with the negative impact of RST (Anderson & Stevenson, in press). Guided by RECAST, the purpose of this article is to describe the development of the Engaging, Managing, and Bonding through Race (EMBRace) intervention targeting the RS practices between Black adolescents and families. Authors explore current research on RST, discuss why traditional coping models for stress are inadequate for racially-specific stressors, highlight RECAST as a burgeoning racial coping and socialization model, and describe how RS can be used as a tool to intervene within Black families. This is followed by a detailed description of the development and use of the EMBRace intervention which seeks to reduce RST through RS psychoeducation and practice, stress management, and the promotion of bonding in Black families. This article aims to serve as an example of a culturally-relevant RS intervention for Black families who may benefit from clinical treatment for psychological distress from racially-discriminatory encounters.

Keywords: racial socialization, discrimination, Black families, intervention, stress management, coping

Clinician: So what are the problems we’re facing today?

Youth: Oh, racism, um…cops killing Black people. Just like, mostly about like, racists. Like, the cops that’s [sic] killing Black people is [sic] White. Did you ever notice that?…

C: How does it feel when you see things like that?

Y: It hurts, cuz one day, it can be anybody, a part of anybody [sic] family. They [sic] takin’ away a life for nothing…

C: Have you and your mom talked about those type of, um, incidents?

Y: No. The news. I talk to the news.. .Like, it’s on TV when I be [sic] in the room by myself…

When asked about society’s current problems, “AJ”, a 10-year old boy, described something that he perceived as particularly challenging in the Black community. In 2017, at least 223 Black Americans were killed at the hands of law enforcement (The Washington Post, 2017). The racial disparity in killings by police officers for people that look like AJ yields at least a three times odds ratio for Black victims relative to Whites (Buehler, 2017; Woodward, 2016). Despite the competence that most public officials display while under stress to protect and serve the community, mass and social media have shone a spotlight on the incongruous use of firearms in cases for which the victims were unarmed or providing legal documentation for their weapon (e.g., Swaine, Laughland, Lartey, & McCarthy, 2015). While specific cases of racial discrimination have perhaps been most amplified with police officers, youth experience frequent racial challenges with teachers, strangers, and peers, in addition to the media (Adams-Bass, Bentley-Edwards, & Stevenson, 2014). When youth are perplexed about injustice, it may be natural to seek understanding and support from family members, which is often provided in the form of racial socialization (RS), defined as verbal and nonverbal messages communicated to youth regarding race (Lesane-Brown, 2006; Stevenson, 2014). Yet discrimination can lead to stress for both parents and youth given the concerns of individual and familial well-being and loss of life (Stevenson, Davis, & Abdul-Kabir, 2001; Thomas & Blackmon, 2015). Exploring how youth like AJ engage in family-based interactions focused on racial discrimination illustrates how clinical interventions that reduce the fear and tragedy of racial encounters are timely and important in today’s highly charged racialized climate. Thus, the aim of this manuscript is to 1) detail the current research on racial discrimination and stress, 2) explore traditional and racially-specific coping models for stress, 3) describe how RS can be used as a coping strategy for Black families’ racial stress, and 4) outline the development of the Engaging, Managing, and Bonding through Race (EMBRace) program – a therapeutic intervention that addresses the stressful psychological consequences of discrimination through the psychoeducation and culturally-relevant practice of RS.

The Effects of Racial Discrimination

Racial discrimination—or the unjust prejudicial treatment of different categories of people due to race (discrimination, n.d.)—has been identified as a primary social stressor for Black adults (Brody et al., 2008), youth (Seaton, Caldwell, Sellers, & Jackson, 2010), and the familial unit (Author et al., 2015; McNeil, Harris-McKoy, Brantley, Fincham, & Beach, 2013). Approximately 90% of Black adults (National Public Radio, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, & Harvard University, 2017) and children between the ages of eight and 16 (Pachter, Bernstein, Szalacha, & Garcia Coll, 2010) report having experienced at least one racially discriminatory event. While younger children may have less formal reasoning when describing and experiencing discriminatory practices (e.g., Gillen-O’Neel, Ruble, & Fuligni, 2011; Seaton, 2010; Spears Brown & Bigler, 2005), adolescents begin to delineate various forms of discrimination (e.g., interpersonal, intercultural, etc.) and describe it uniquely relative to adults (Seaton, 2006). For younger adolescents with pre-formal cognitive development reasoning, racism has been negatively associated with their self-esteem (Seaton, 2010). For older adolescents, experiences of racial discrimination, moderated by gender, age, and stress levels, has been related to alcohol consumption (Metzger et al., 2018; Terrell, Miller, Foster, & Watkins, 2006). Within the family, Black parents who perceive more discriminatory experiences rate their children as having greater internalizing (Simons et al., 2002) and externalizing (McNeil et al., 2013) problems. Furthermore, parents who perceive more discriminatory events may also experience impaired psychological functioning and parenting practices, which, in turn, are associated with greater child emotional problems (Author et al., 2015).

Racial discrimination impacts families.

Developing Black youth are often influenced by the stressors of the environmental context and the socialization and parenting practices of their families (see McLoyd, 1990; 1998). Given the effects of discrimination, it is important to understand in what ways the sociocultural environment impacts the developmental competencies of youth. In particular, Ecological Systems Theory (Bronfenbrenner, 1979) indicates that all children are embedded within the ecology of the family in which development occurs. Still, researchers, interventionists, and therapists have challenges understanding child development for children of color within a microsystem (e.g., family) with respect to the greater exosystem (e.g., neighborhood) and macrosystem (e.g., racial segregation) (Greenspan, 2002). In alignment with the Ecological Systems theory, youth of color do develop within these concentric systems, however, Garcia Coll and colleagues (1996) underscored the importance of conceptualizing sociocultural experiences as dynamic and central to youth development over time across systems. The Integrative Model for the Development of Minority Children posits that social determinants like discrimination have a direct and dynamic role in shaping the adaptive culture (e.g., residential segregation, socioeconomic status, school choice, etc.; Gee, Walsemann, & Brondolo, 2012) and familial practices (e.g., RS, traditions, etc.) in the lives of youth of color.

Discriminatory practices impact family systems in utero, birth, and throughout the development of the child. In the Weathering Hypothesis (Geronimus, 1992), for example, infant mortality among African American women is theorized as a result of living and coping with cumulative stressors (e.g., racial, socioeconomic) over time. Even though infant and maternal health fare better within-group when Black mothers are younger, there are still discrepancies with familial health outcomes between groups due to social risk factors, such that Black mothers and their children tend to have two to three times the rate of infant deaths, maternal deaths, preterm births, and low birth weight relative to their White and Hispanic counterparts (Norris, 2011), regardless of income or educational level (Mustillo et al., 2004). Throughout pregnancy, mothers may pass on stress-related symptomatology to the fetus in utero (Yehuda & Bierer, 2009). These epigentic transmissions from parent to child also underscore the multi-generational expression of stress reactions and the development of traumatic responses to environmental influences (e.g., Post-Traumatic Slave Syndrome; DeGruy, 2005; Goosby & Heidblink, 2013).

Racial stress and trauma.

Within the literature, stress and trauma resulting from racial discrimination has been referred to as race-based traumatic stress, racial stress and trauma, and racism-related stress (e.g., Carter, 2007; Franklin, Boyd-Franklin, & Kelly, 2006; Harrell, 2000; Stevenson, 2014). Researchers have conceptualized this group of stressors (subsequently referred to as racial stress and trauma; RST) as the trauma borne out of racially discriminatory experiences. This trauma can manifest before, during, or after a racial encounter (Carter, 2007) and is defined as the “race-related transaction between individuals or groups and their environment…that are perceived to tax or exceed existing individual and collective resources or threaten well-being” (Harrell, 2000; p.44). RST in adults has been linked to increased psychological distress, depression, and anxiety (Polanco-Roman, Danies, & Anglin, 2016; Utsey et al., 2002) and also affects their ability to effectively identify and appraise stressors (Stevenson, Reed, Bodison, & Bishop, 1997). Black children and adolescents become particularly vulnerable to racialized stress as they progress through developmental stages, evidenced by poorer sleeping habits and internalizing and externalizing problems (Simons et al., 2002). Similar to adults, RST impedes youth’s ability to effectively appraise stressors following a racial encounter (Stevenson, et al., 1997). Given that RST in Black families is an especially damaging form of stress and manifests in family systems distinctly from other stressors (e.g., Author et al., 2015), specific socialization strategies for racial matters are important.

Coping with Racial Discrimination

Racial socialization.

To protect youth from the deleterious impact of discrimination, some Black parents provide racially-specific socialization strategies and culturally-relevant parenting behaviors (Berket et al., 2009). Racial socialization, or the verbal and nonverbal racial communication between families and youth (Hughes et al., 2006), has been identified as a protective factor in a host of academic and emotional well-being outcomes for youth depending on the frequency and type of utilization of its four tenets. Cultural socialization, or messages and behaviors that emphasize cultural pride, heritage, and ancestral legacy (Hughes et al., 2006), has been associated with greater academic achievement (Neblett, Phillip, Cogburn, & Sellers, 2006; Wang & Hughley, 2012), the development of appraisal and coping skills (Gatson, 2011; Neblett, Rivas-Drake, & Umana-Taylor, 2012), fewer depressive symptoms (Liu & Lau, 2013), and the development of racial identity (Murry, Berkel, Brody, & Miller, 2009). Preparation for bias, or parental efforts to promote children’s awareness of discrimination and subsequent coping processes (Hughes, et al., 2006), is used most when parents perceive greater racial discrimination (Gatson, 2011; Thomas, Caldwell, & DeLoney, 2012), particularly after a prevalent event (e.g., shooting of Trayvon Martin; Thomas & Blackmon, 2015). Studies indicate that preparation for bias is positively associated with approach and active coping (Caughy, Nettles, & Lima, 2011; Gatson, 2011).

Promotion of mistrust is a warning to distrust those from other races (Hughes et al., 2006). Most notably, the literature has found that promotion of mistrust is associated with greater risk to mental health outcomes (e.g., depression) and socio-emotional development (e.g., less optimism and greater pessimism) for Black youth (Liu & Lau; 2013). In addition, parents’ retrospective childhood RS experiences reflect similarly negative outcomes. Gatson (2011) found that parents who received frequent messages about promotion of mistrust during childhood reported more negative emotional and physical experiences with racism. As such, promotion of mistrust may foster negative attitudes about others more than positive attitudes about oneself or one’s group, and it has not been shown to predict ethnic identity exploration or commitment in youth (Else-Quest & Morse, 2015). Finally, egalitarianism, or the assertion that race is not a factor that should be discussed or that will hamper one’s ability to succeed (Hughes et al., 2006), has the least empirical evidence in Black families due to its relatively low frequency (White-Johnson, Ford, & Sellers, 2010). Yet the extant literature indicates that there are positive outcomes associated with egalitarianism when used with other RS strategies (Cooper, Smalls-Glover, Neblett & Banks, 2015), specifically regarding self-concept when used with cultural socialization (Neblett et al., 2012).

Problems with racial coping.

In a general theorization of stress and coping, Lazarus and Folkman (1984) indicated that when an individual feels taxed beyond their ability to meet the demand, coping becomes a challenge depending upon how they appraise the impact of the stressor (e.g. a challenge, positive, or a threat). Problem-based coping would suggest that an individual would seek to gain control over the stressor to engage in several strategies to define and manage the stressor. Although Lazarus and Folkman’s theory is accepted for most stressors, scholars have continued to challenge various components of the framework involving racially-specific stressors. The chronic impact of discrimination on stress (Ong, Fuller-Rowell, & Burrow, 2009) has been shown to influence how an individual appraises it as a stressor (Outlaw, 1993), whether it be for overt (Bennett, Merritt, Edwards, & Sollers, 2004), systematic (Feagin, 2013), daily (Banks, Kohn-Wood, & Spencer, 2006), and/or ambiguous (e.g., microaggressions; Sue et al., 2007) experiences. Additionally, Black Americans report greater difficulty with appraising and more frequent avoidant coping relative to other racial groups facing discriminatory experiences (King, 2005; Sanders Thompson, 2006).

Racial Encounter Coping Appraisal and Socialization Theory (RECAST).

Although the frequent practice of some RS components has been associated with more desirable outcomes, a question remains: how does RS address racialized stress? In an attempt to reconcile the racially-specific appraisal challenges and potentially beneficial RS practices in Black families, the Racial Encounter Coping Appraisal and Socialization Theory (RECAST; Author & Author, in press; Author, 2014) endeavors to elucidate mechanisms involved in coping with racial discrimination. RECAST proposes that how an individual performs primary and secondary stress appraisals of racially discriminatory experiences determines subsequent coping through multiple pathways. The initial appraisal of racial encounters depends upon one’s exposure, experience, and previous application of RS and coping skills. The model explains how racial stressors may be conceptualized (e.g., threat, challenge, or insignificant), the extent to which individuals consider themselves able to control or manage the racialized stressor (e.g., coping self-efficacy), the method through which the individual aims to cope with this racialized stressor (e.g., approach-oriented coping), and the extent to which the employed coping strategies manifest desired results (e.g., positive or negative outcomes; Provencher, 2007). Racial socialization processes are conceptualized to protect against RST and resolve racial encounters by promoting the development of healthy racial coping skills (please see Author & Author (in press) for a full description of the theory).

Families push back on racial discrimination.

Since coping plays a large role in the way youth and adults both perceive and react to discriminatory events, the management and intervention of coping strategies may play a critical role in psychological wellness. As posited by RECAST, RS practice allows youth and parents to navigate racial experiences prior to, during, and after a racial encounter. With approach-oriented RS, it is expected that the confusion of these stressful encounters is reduced and one’s confidence, or racial coping self-efficacy, grows. By using emotion regulation and relaxation strategies (Author, 2003; Author, 2014), Black families have a way to push back on distressful subtle and blatant racism from malicious or well-meaning encounters.

Studies have shown that Black women who perceive racial discrimination and have higher levels of problem-focused coping may have fewer depressive symptoms (West, Donovan, & Roemer, 2010). Conversely, greater avoidant coping was associated with greater depressive symptoms in the face of racial discrimination (West et al., 2010). Moreover, Black youth who report greater perceived control over racial experiences indicate more frequent approach coping strategies (e.g., seeking social support and problem-solving strategies; Scott & House, 2005), a technique that may be beneficial in reducing internalizing and externalizing problems associated with perceived discrimination. Indeed, youth who report more frequent RS also indicate using more engaged coping strategies beyond that found solely from generalized coping socialization practices (Author, Jones, Anyiwo, McKenny, & Gaylord-Harden, in press). Thus, approach-oriented racial communication within families may be mutually beneficial for parents and adolescents hoping to alleviate the stress experienced from racial discrimination (e.g., Author et al., 2018). As such, a second important question emerges: how can families improve their coping skills and socialization practices? A new intervention grounded in RS research and the RECAST framework endeavors to address this inquiry.

The Engaging, Managing, and Bonding through Race (EMBRace) Intervention

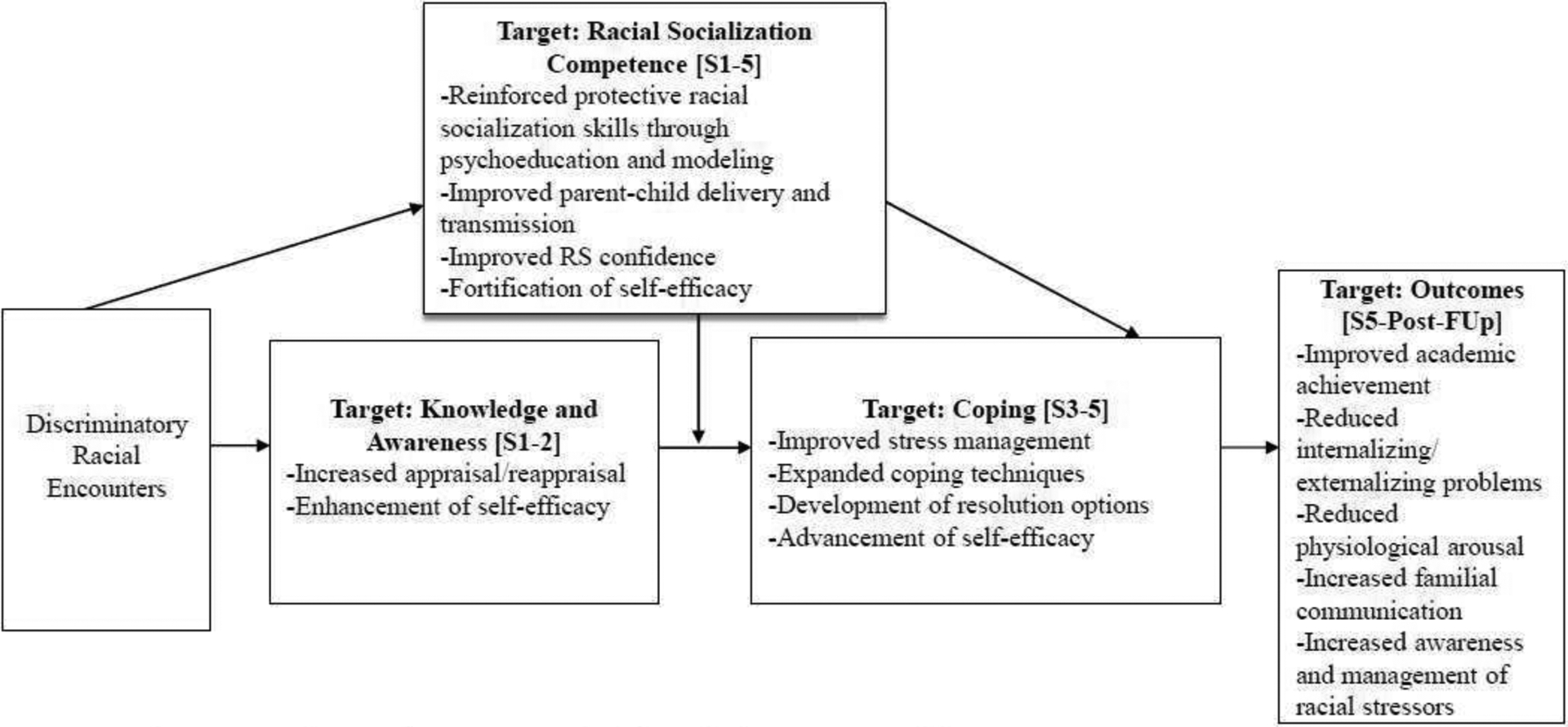

Grounded in RECAST theory, The Engaging, Managing, and Bonding through Race (EMBRace) program is a 5-session RS intervention for Black youth ages 10–14 and at least one of their caregivers1. EMBRace’s mission is to be a culturally-based therapeutic intervention that empowers African American youth and families to confront racial stress and trauma together. EMBRace’s vision is to provide African American youth and families with tools and skills to resolve racial trauma and reduce racial stress in an effort to promote healthy coping for racial encounters. The goals of EMBRace are to equip Black families with the tools to 1) engage in bidirectional conversations on race based on psychoeducation from the RS literature, 2) manage RST through healthy approach coping strategies, and 3) foster bonding between parent and child through parent-child communication and strengthening of the parent-child relationship (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The EMBRace intervention as conceptualized through the RECAST model.

Note. S = Session, Post = Posttest, FUp = Follow-up

The intervention requires seven weeks to complete, including a pre-test, five content sessions, and a post-test. Each therapeutic session lasts 90 minutes, while pre- and post-tests require 120 minutes, respectively. EMBRace is designed for clients as individuals (e.g., adolescents and parents separately) and conjointly (e.g., parent-adolescent dyads), and is not a group-level intervention. EMBRace sessions are implemented by trained clinicians while trained research assistants collect data during pre- and post-tests.

The aim of the EMBRace intervention is not to endorse the use of any racial socialization tenet over another or instruct parents on what messages to explicitly communicate to their child. Rather, EMBRace seeks to provide clinical strategies pursuant to and psychoeducation regarding RS, particularly as it pertains to tenets that have been associated with negative well-being outcomes (e.g., promotion of mistrust). By offering psychoeducation and enhanced coping methods, the developers seek to respect the autonomy of families in communication while also exploring in what ways RST contributes to RS strategies. The desired outcome is healthy racial coping and families feeling more competent in their ability to engage in RS with their children. For preliminary feasibility and outcome data with coping responses, please refer to prior publications (Author et al., 2018a; Author et al., 2018b). We present a description of the development, training, and session components below.

Program and manual development.

The EMBRace program was initially developed from a proposal submitted to a postdoctoral fellowship by the first author with mentorship from the last author. After acquiring the fellowship, the first author began meeting with undergraduate, masters’, and doctoral students and postdoctoral trainees to construct the mission and vision of the program as well as the content of the sessions. The EMBRace manual was created over the span of four months by this multidisciplinary team of eight individuals with backgrounds in counseling, clinical psychology, education, social work, and human development. Each EMBRace session was assigned to a pair of researchers and/or clinicians who completed a literature review on the respective RS construct and incorporated developmentally-appropriate activities for clients. The team incorporated elements of Trauma Focused-Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT) for trauma reduction (i.e., PRACTICE skills; Cohen & Mannarino, 2008), Parent Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT) for parent-child relationships (i.e., PRIDE; Eyberg, Boggs, & Algina, 1995), RECAST for a racially-specific stress and coping theory (Stevenson, 2014), and steps suggested for racial healing (Hardy, 2013) to guide session creation. The original manual was reviewed and edited by the program developers (i.e., first and last authors), with edits pertaining to whether to utilize four or five sessions, whether to provide both individual and conjoint sessions, and in what ways to best describe psychoeducation to participants. Feedback from community advisory groups was also implemented for participant acceptability (e.g., changing the term “homework” to “funwork”). From the development team, a Program Coordinator (second author) was selected. The coordinator made edits to the intervention manual related to formatting, clarification of terms/prompts, and ease of use for clinicians over the three years the program has been implemented, however, content has remained largely unchanged.

Clinician and research assistant training.

Research assistants and clinicians were recruited from the university in which the intervention was developed, neighboring universities, and community organizations that provided therapeutic services. Clinicians and research assistants interviewed with the intervention leadership before being invited to training. All trainings for research assistants and clinicians began with exploration of sociocultural identities and social privilege. This training aimed to help clinicians understand their social positioning, identify potential biases, and examine how their identities may influence the clinical space in an RS intervention. This personal exploration was followed by a training on the theory of change and intervention rationale including a presentation of the literature on racial discrimination, RECAST, and racial coping strategies.

Following this initial sociocultural training session, the Program Coordinator trained research assistants for three hours on informed consent/assent, administering assessments, intervention protocol, and research assistant tasks. Informed consent and assent protocols were discussed in detail to ensure comfort for both parent and child participants. Quantitative and qualitative surveys were reviewed so that research assistants would be equipped to answer potential questions about the items. Qualitative interviewing was practiced allowing for a more conversational tone and rapport building with families. Research assistants were also trained on how to administer the observational assessment. Bi-weekly research meetings were held to support research assistants and monitor progress.

Clinicians completed a 3-hour training on theory of change, intervention rationale, and intervention protocols led by the first author. The EMBRace manual was reviewed in detail and clinicians practiced facilitating these sessions through role-playing. Clinicians were encouraged to develop a clinical toolbox, with techniques and practices relevant to discussing racial issues with families. Among these skills were methods to encourage parent and child communication, modeling correction, and reinforcing positive communication between the dyad. Following the initial pilot, audio and video recording from previous sessions were used in training to model effective facilitation. The close of the training centered on the structure of the required weekly supervision meetings and identifying additional support for clinicians.

Overview and session content. Pre-test.

The aim of the pre-test is to collect demographic information, informed consent/assent for participation, and quantitative, qualitative, and observational assessments of the family. It is also the first time families meet with EMBRace staff, so a primary goal is to establish rapport and thoroughly explain the program. Within this session, the researchers seek to gain baseline data concerning parent and child’s racial experiences, beliefs, communication, and past and current parent-child relationship. Following informed consent and assent, the pre-test session consists of three components, including quantitative measures, qualitative interviews, and an observational assessment. Within the quantitative measures, the parent and child independently complete surveys via iPad with the assistance of the trained research assistants. Although the vast majority of quantitative measures have been utilized and validated in prior research (e.g., the Child Behavior Checklist, the Racism and Life Experiences Scale, the Parent Adolescent Relationship Scale, etc.), several new measures were created to capture experiences specific to hypothesized changes in EMBRace (e.g., Racial Socialization Competency Scale; Author, Jones, & Author, under review; Stress of Talking to Children about Race; unpublished, etc.). The open-ended qualitative interview, verbally administered by a research assistant, assesses the RS experiences and practices of parent and child, familial support, and parent-child relationship. The final component of the pre-test is a five-minute observational assessment (modeled after the Five Minute Speech Sample; e.g., Weston, Hawes, & Pasalich, 2017) in which the parent and child are given a scripted racially-charged vignette and asked to discuss the situation as they would normally. The research assistant presents the typed vignette and leaves the room while an audio and/or video recorder captures the observation.

Sessions 1–5.

The sessions are each guided by one tenet of RS as outlined in the literature (i.e. cultural socialization in week 1, preparation for bias in week 2, promotion of distrust in week 3, and egalitarianism in week 4; Hughes et al., 2006) with a fifth session that allows families to review and practice skills (please see Table 1). EMBRace seeks to provide a safe context in which families are able to practice conversations based on each tenet of RS. Given that there are mixed findings within the literature on the utility of each tenet, the central goal of EMBRace is to provide the rationale and facilitate competence associated with the use of each tenet. In particular, week 3, which focuses on promotion of distrust, is supported by TF-CBT trauma narratives in which the clinician seeks to support the reason why one would want or feel the need to use such a generalized strategy. As such, the use of graduated coping strategies, which are also associated with the intensity of dialogue per session, help to complement the intensified conversation around racial encounters. Coping strategies include racial encounter knowledge, racial encounter stress management, and explicit racial coping. The strategies comprise the ability to recognize racial discrimination, accurately appraise the stress of self and others, reduce one’s stress, engage instead of avoid, and finally resolve toward healthy outcomes.

Table 1.

Overview of intended EMBRace skills and processes by session.

| Session | Content | Process | Delivery |

|---|---|---|---|

| Session 1 “Say it Loud!” | Cultural Pride | Racial Encounter Knowledge | Affection |

| Session 2 “We Gon’ Be Alright!” | Preparation for Bias | Racial Encounter Knowledge | Protection |

| Session 3 “I Got Enemies, Got a Lot of Enemies.” | Promotion of Distrust | Racial Encounter Stress Management | Correction |

| Session 4 “Does it Matter if You’re Black or | Egalitarianism | Racial Encounter Stress Management | Connection |

| Session 5 “Ain’t No Stopping Us Now!” | Applied Skills | Racial Encounter Coping | Applied Skills |

Within each session, the allotted 90 minutes are segmented into three components. The first 30 minutes consist of concurrent individual meetings for the parent and child to talk with their own clinicians about their racial experiences and RST given that there may be traumatic racial experiences that the parent has had that s/he is not ready to discuss with the child and vice versa. Following this 30-minute segment, families break for dinner provided by the intervention staff for approximately 15 minutes. The break allows for downtime and a natural environment in which families and staff can build rapport outside of the confines of manualized content. The remaining 45 minutes of the session is the dyadic portion when the parent, child, and their clinicians come together. Still guided by the RS tenet for the session, clinicians facilitate conversation and activities between parent and child. These activities vary week-to-week and are outlined in the intervention manual. Dyadic activities include, but are not limited to, debating, matching games, crafting a family tree, and discussing media. The dyadic session is mainly important in that it reinforces parent-child bonding and communication skills. As stipulated within the RECAST model, clinicians are asked to model appropriate affection (e.g., unconditional love and support), protection (e.g., loving supervision), correction (e.g., loving confrontation and accountability), and connection (e.g., application between family and external systems) within the session (Author et al., 2001). Once the dyadic activities have been completed, clinicians review the outlined “funwork” with the family and address any transportation or scheduling needs.

Sample session. In an excerpt from the dyadic portion of Session 1, elements of RS (i.e., cultural socialization), coping (e.g., racial knowledge), and bonding (e.g., affection) are emphasized through a parent-child art activity of co-creating a cultural family tree:

CLINICIAN: “…For our family discussion, we will talk about what you have each talked about separately.”

CLINICIAN: “Can you share with one another something that you took away from your individual sessions? Something that possibly stuck with you that you may want each other to know?”

…

CLINICIAN: “After our first meeting, we asked you to begin some research on your community, your ancestors, and your family members. Now we are going to take that research and work together to create a cultural family tree.”

CLINICIAN: “Begin by drawing the roots of your tree in the middle of the poster and place throughout your tree people who are important to you. Include a fun fact about why these people are important or something special about them.”

CLINICIAN: “Draw a circle around your tree and then write/draw about the place, people, and traditions/style in your community or in your family that keep you together or inspire you.”

STOP: Supply the parent and child with the necessary art supplies and allow them to draw for approximately 15 minutes.

…

CLINICIAN: “What is important to you in the tree?”

CLINICIAN: “Why are these people important to you?”

CLINICIAN: “Is there anything else you want to learn about your culture that you would have liked to include in your tree?”

CLINICIAN: “How will you make a plan to discover it?”

CLINICIAN: “How does knowing about your culture make you feel about some of that racial stress that we talked about earlier?”

CLINICIAN: “Is there anything else you all would like to discuss before we end?”

CLINICIAN: “Thank you for expressing your feelings andjoining us today – we look forward to having you again next week.”

STOP: Review funwork with family.

Funwork. Homework, or “funwork”, is outlined for each session in the participant manual. Families are asked to do activities and watch media related to the tenet of RS that was reviewed that week or is forthcoming. This allows the parent and child to reinforce the skills they learned in session, explore material prior to the session, and bond outside of the intervention. A participant manual that mirrors the therapist manual is supplied to each family with instructions for each week’s assignment and a summary of the session in developmentally appropriate language (e.g., [for the sample session] “Brainstorm about your family and cultural tree. Try to recall important people, places, and things that are important in your immediate family or in your heritage, like we did with cultural socialization today.”).

Post-test.

The post-test is administered by research assistants. The same quantitative and observational assessments are administered to the parent and child as the pre-test. The qualitative interview is modified to solicit participant feedback about their clinicians and the intervention (e.g., “What did you like about EMBRace? What would you suggest we do differently next time?”). This evaluation includes questions on clinician preferences (e.g., cultural match), perceived benefit of the intervention, and whether participants would recommend the program to families they know. At the close of post-test, families will receive final compensation (totaling $100), a certificate of completion, and materials donated by community partners.

Additional clinical considerations.

It is our hope that the EMBRace program has meaningfully contributed to both families and clinicians. During the three years of trainings and implementation, clinicians have anecdotally and quantitatively indicated the impact that it has had on their understanding of Black family stressors (Author et al., 2018b). Additionally, as a targeted intervention, the stand-alone protocol can be used for Black clients of all psychological well-being, not just those with a clinical diagnosis. Although it has only been implemented in urban areas, clients have comprised a variety of financial, educational, regional, and residential backgrounds. And, while some clients initially believed that the time commitment would be prohibitive, the vast majority of qualitative data actually suggest that families desired more time per session and over additional weeks. Finally, families who have completed the funwork remark on how enjoyable it was and how they planned on sharing the resources with other families.

Overview of the research plan.

To better understand the effectiveness of EMBRace, we plan for 40 10-to-14-year-old youth and at least one of their parents to be recruited for a waitlist-control trial. Each family will be assigned to a conditional (i.e. experimental or wait-list control) group. The incentive for each family will include gift cards in the amount of $25 at pre-test, $25 at session 2, and $50 at post-test for a total of $100 per family for a completed trial. Furthermore, local family-based and community organizations will be solicited for contributions to the families (e.g., discounted tickets to the theater, books, etc.). Participants will be recruited within the community via social and local media (e.g., Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, radio, etc.), public transportation posts, school distributions, and local neighborhood advertisements (e.g., places of worship, barbershops/beauty salons, community centers, etc.).

During the pre- and post-test, participants will respond to quantitative measures via an iPad to reduce positive impression management between the participant and researchers. Items will be recorded and available audibly if the participant is unable to read the question. Finally, parent-child tasks will be video and/or audio taped for observational assessment. Throughout the intervention, trained facilitators will provide the EMBRace protocol and collect repeated measures on stress from participants. Data will continue to be gathered via quantitative, qualitative, and observational methodology. Six-week follow-ups will assess the maintenance of intervention effects as well as the contribution to long-term familial, academic, psychological, and physiological outcomes.

Summary

The main purpose of this article was to describe the development of the EMBRace protocol. The primary goal of the EMBRace intervention is to provide youth and families with the tools to address racial discrimination and RST through the development of healthy coping strategies. The authors anticipate that this article can contribute to the literature on applied uses of RS and to other researchers seeking to develop a culturally-relevant intervention for Black youth and families. The authors have utilized relevant work from academic literature on RS, RST, coping, and racially-relevant stress and coping theories to develop the EMBRace intervention. EMBRace is the application of RECAST, which posits that healthy coping for racial encounters can be achieved through the intentional practice of RS. Distinct from traditional stress and coping models, RECAST addresses racialized stressors to confront the avoidant coping strategies typically employed in discriminatory encounters. EMBRace incorporates tangible and approach-oriented coping skills (i.e. journaling, relaxation) as proactive and reactive strategies to counteract discriminatory encounters. These skills are taught in each of the five content sessions and assessed at pre- and post-test. Overall, this intervention seeks to serve as a resource for Black families to promote healthy communication and positive coping within parent-child dyads through RS and approach-related coping strategies. EMBRace was developed particularly for Black families—like AJ and his mother—who may benefit from racially-specific treatments for psychological distress in order to engage, manage and bond through racially stressful encounters.

Acknowledgments

The authors are incredibly grateful for the tremendously hard work and long days put forth by the full development team: Dr. Kelsey Jones, Dr. Jason Javier-Watson, Dr. Lloyd Talley, Nneka Ibekwe, Jeff Baker, and Steve Delturk, Additional thanks goes to our clinicians, community partners, #TeamEMBRace and, with greatest gratitude, our EMBRace families.

Footnotes

Inclusion criteria states “caregivers” as opposed to parents. The term “caregiver” is inclusive of biological parents, adoptive parents, foster parents, grandparents, etc. Caregivers are henceforth referred to as parents. More than one parent is eligible to participate.

References

- Adams-Bass V, Bentley-Edwards K, & Stevenson H (2014). That’s not me I see on TV…: African American youth interpret media images of black females. Women, Gender, and Families of Color, 2, 79–100. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Author, Hussain S, Wilson M, Shaw D, Dishion T, & Williams J (2015). Pathways to Pain: Racial Discrimination and Relations Between Parental Functioning and Child Psychosocial Well-Being. Journal of Black Psychology, 41, 491–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Author, Jones SCT, Anyiwo N, McKenny M, & Gaylord-Harden N (revised). What’s race got to do with it? The contribution of racial socialization to Black adolescent coping. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Author, Jones SCT, Navarro C, McKenny M, Mehta T, & Stevenson H (2018). Addressing the mental health needs of vulnerable Black American youth and families: A case study from the EMBRace intervention. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health; Special Issue on The Health Needs of Vulnerable Children: Challenges and Solutions, 15, 898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Author, McKenny M, Mitchell A, Koku L, & Author (2018). EMBRacing racial stress and trauma: Preliminary feasibility and coping outcomes of a racial socialization intervention. Journal of Black Psychology, 44, 25–46. [Google Scholar]

- Author & Author (accepted; special issue). RECASTing racial stress and trauma: The healing role of racial socialization in Black families. [Google Scholar]

- Banks K, Kohn-Wood L, & Spencer M (2006). An examination of the African American experience of everyday discrimination and symptoms of psychological distress. Community Mental Health Journal, 42, 555–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett G, Merritt M, Sollers III J, Edwards C, Whitfield K, Brandon D, & Tucker R (2004). Stress, coping, and health outcomes among African-Americans: A review of the John Henryism hypothesis. Psychology & Health, 19, 369–383. [Google Scholar]

- Brody G, Chen Y, Kogan S, Murry V, Logan P, & Luo Z (2008). Linking perceived discrimination to longitudinal changes in African American mothers’ parenting practices. Journal of Marriage and Family, 70, 319–331. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U (1979). Contexts of child rearing: Problems and prospects. American psychologist, 34, 844. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant-Davis T, & Ocampo C (2005). Racist incident–based trauma. The Counseling Psychologist, 33, 479–500. [Google Scholar]

- Buehler J (2017). Racial/Ethnic Disparities in the Use of Lethal Force by US Police, 2010–2014. American Journal of Public Health, 107, 295–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butts H (2002). The black mask of humanity: Racial/ethnic discrimination and post-traumatic stress disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, 30, 336–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter R (2007). Racism and psychological and emotional injury: Recognizing and assessing race-based traumatic stress. The Counseling Psychologist, 35, 13–105. [Google Scholar]

- Caughy M, Nettles S, & Lima J (2011). Profiles of racial socialization among African American parents: Correlates, context, and outcome. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 20, 491–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark R, Anderson N, Clark VR, & Williams D (1999). Racism as a stressor for African Americans: A biopsychosocial model. American psychologist, 54, 805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, & Mannarino A (2008). Trauma- Focused cognitive behavioural therapy for children and parents. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 13, 158–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coll CG, Crnic K, Lamberty G, Wasik B, Jenkins R, Garcia H, & McAdoo H (1996). An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child development, 67, 1891–1914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins J, David RJ, Handler A, Wall S, & Andes S (2004). Very low birthweight in African American infants: the role of maternal exposure to interpersonal racial discrimination. American journal of public health, 94, 2132–2138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper S, Smalls-Glover C, Neblett E, & Banks KH (2015). Racial socialization practices among African American fathers: A profile-oriented approach. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 16, 11. [Google Scholar]

- DeGruy J (2005). Post traumatic slave syndrome. Joy DeGruy RSS. [Google Scholar]

- Discrimination. (n.d.) In Oxford Living Dictionary. Retrieved from https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/discrimination

- Else-Quest N & Morse E (2015). Ethnic variations in parental ethnic socialization and adolescent ethnic identity: A longitudinal study. Cultural Div and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 21, 54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyberg SM, Boggs SR, & Algina J (1995). Parent-child interaction therapy: A psychosocial model for the treatment of young children with conduct problem behavior and their families. Psychopharmacology Bulletin, 31, 83–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feagin J (2013). Systemic racism: A theory of oppression. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Franklin AJ, Boyd-Franklin N, & Kelly S (2006). Racism and invisibility: Race-related stress, emotional abuse and psychological trauma for people of color. Journal of Emotional Abuse, 6, 9–30. [Google Scholar]

- Frazier SL, Abdul- Adil J, Atkins MS, Gathright T, & Jackson M (2007). Can’t have one without the other: Mental health providers and community parents reducing barriers to services for families in urban poverty. Journal of Community Psychology, 35, 435–446. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller-Rowell T, Evans G, & Ong A (2012). Poverty and health the mediating role of perceived discrimination. Psychological Science, 23, 734–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatson JD (2011). Racial socialization, racial discrimination and mental health among African American parents. (Doctoral Dissertation) University of California, Los Angeles. [Google Scholar]

- Gee G, Walsemann K, & Brondolo E (2012). A life course perspective on how racism may be related to health inequities. American Journal of Public Health, 102, 967–974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geronimus AT (2000). Understanding and eliminating racial inequalities in women’s health in the United States: the role of the weathering conceptual framework. Journal of the American Medical Women’s Association (1972), 56, 133–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillen- O’Neel C, Ruble DN, & Fuligni AJ (2011). Ethnic stigma, academic anxiety, and intrinsic motivation in middle childhood. Child development, 82, 1470–1485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goosby BJ, & Heidbrink C (2013). The Transgenerational Consequences of Discrimination on African-American Health Outcomes. Sociology compass, 7, 630–643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenspan SI (2002). The secure child: Helping children feel safe and confident in a changing world. Cambridge, MA, US: Perseus Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Griffith DM, Childs EL, Eng E, & Jeffries V (2007). Racism in organizations: The case of a county public health department. Journal of community psychology, 35, 287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy KV (2013). Healing the hidden wounds of racial trauma. Reclaiming Children and Youth, 22, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Harrell SP (2000). A multidimensional conceptualization of racism-related stress: implications for the well-being of people of color. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 70, 42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helms JE, Nicolas G, & Green CE (2012). Racism and ethnoviolence as trauma: Enhancing professional and research training. Traumatology, 18, 65. [Google Scholar]

- Hope EC, Skoog AB, & Jagers RJ (2015). “It’ll Never Be the White Kids, It’ll Always Be Us” Black High School Students’ Evolving Critical Analysis of Racial Discrimination and Inequity in Schools. Journal of Adolescent Research, 30, 83–112. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Rodriguez J, Smith EP, Johnson DJ, Stevenson HC, & Spicer P (2006). Parents’ ethnic-racial socialization practices: a review of research and directions for future study. Developmental Psychology, 42, 747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus R, & Folkman S (1984). Coping and adaptation. The handbook of behavioral medicine, 282–325. [Google Scholar]

- Lee D & Ahn S (2013). The relation of racial identity, ethnic identity, and racial socialization to discrimination–distress: A meta-analysis of Black Americans. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 60, 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, & Lau A (2013). Teaching about race/ethnicity and racism matters: an examination of how perceived ethnic racial socialization processes are associated with depression symptoms. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 19, 383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khaylis A, Waelde L, & Bruce E (2007). The role of ethnic identity in the relationship of race-related stress to PTSD symptoms among young adults. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 8, 91–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King K (2005). Why is discrimination stressful? The mediating role of cognitive appraisal. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 11, 202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauro R, Sato K, & Tucker J (1992). The role of appraisal in human emotions: A cross-cultural study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 62, 301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd V (1990). Minority children: Introduction to the special issue. Child Dev, 61, 263–266.2344776 [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd V (1998). Socioeconomic disadvantage and child development. American psychologist, 53, 185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil, Harris-McKoy D, Brantley C, Fincham F, & Beach SR (2014). Middle class African American mothers’ depressive symptoms mediate perceived discrimination and reported child externalizing behaviors. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 23, 381–388. [Google Scholar]

- Metzger I, Salami T, Carter S, Halliday-Boykins C, Anderson R, Jernigan M, & Ritchwood T (2018). Experiences with racial discrimination and drinking habits: The moderating roles of perceived stress for African American emerging adults. Journal of Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murry V, Berkel C, Brody G, Miller S, & Chen Y (2009). Linking parental socialization to interpersonal protective processes, academic self-presentation, and expectations among rural African American youth. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 15, 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustillo S, Krieger N, Gunderson EP, Sidney S, McCreath H, & Kiefe CI (2004). Self-reported experiences of racial discrimination and Black–White differences in preterm and low-birthweight deliveries: the CARDIA Study. American Journal of Public Health, 94, 2125–2131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Public Radio, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, & Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health (2017) Discrimination in America: Experiences and views of African Americans. Princeton, NJ: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Neblett E, Philip C, Cogburn C, & Sellers R (2006). African American adolescents’ discrimination experiences and academic achievement: Racial socialization as a cultural compensatory and protective factor. Journal of Black psychology, 32, 199–218. [Google Scholar]

- Neblett E, Rivas- Drake D, & Umaña- Taylor A (2012). The promise of racial and ethnic protective factors in promoting ethnic minority youth development. Child Development Perspectives, 6, 295–303. [Google Scholar]

- Norris M (Producer) (2011) Why Black women, infants lag in birth outcomes. [Radio episode] Washington, D.C. National Public Radio. [Google Scholar]

- Ong AD, Fuller-Rowell T, & Burrow AL (2009). Racial discrimination and the stress process. Journal of personality and social psychology, 96, 1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachter LM, Szalacha LA, Bernstein BA, & García Coll C (2010). Perceptions of racism in children and youth (PRaCY): Properties of a self-report instrument for research on children’s health and development. Ethnicity & health, 15, 33–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieterse A, Carter RT, Evans S, & Walter R (2010). An exploratory examination of the associations among racial and ethnic discrimination, racial climate, and trauma-related symptoms in a college student population. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 57, 255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polanco-Roman L, Danies A, & Anglin DM (2016). Racial discrimination as race-based trauma, coping strategies, and dissociative symptoms among emerging adults. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 8, 609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Outlaw FH (1993). Stress and Coping: The influence of racism the cognitive appraisal processing of African Americans. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 14, 399–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quintana SM (1998). Children’s developmental understanding of ethnicity and race. Applied and Preventive Psychology, 7, 27–45. [Google Scholar]

- Rollins V, & Valdez J (2006). Perceived racism and career self-efficacy in African American adolescents. Journal of Black Psychology, 32, 176–198. [Google Scholar]

- Scott L, & House L (2005). Relationship of distress and perceived control to coping with perceived racial discrimination among black youth. Journal of Black Psychology, 31, 254–272. [Google Scholar]

- Seaton E (2010). The influence of cognitive development and perceived racial discrimination on the psychological well-being of African American youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39, 694–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaton EK, Caldwell CH, Sellers RM, & Jackson JS (2010). An intersectional approach for understanding perceived discrimination and psychological well-being among African American and Caribbean Black youth. Developmental psychology, 46, 1372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers R, Caldwell C, Schmeelk-Cone K, & Zimmerman M (2003). Racial identity, racial discrimination, perceived stress, and psychological distress among African American young adults. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 44, 302–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons R, Murry V, McLoyd V, Lin K, Cutrona C, & Conger R (2002). Discrimination, crime, ethnic identity, and parenting as correlates of depressive symptoms among African American children: A multilevel analysis. Development and Psychopathology, 14, 371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sotero M (2006). A conceptual model of historical trauma: Implications for public health practice and research. Journal of Health Disparities Research and Practice, 1, 93–108. [Google Scholar]

- Spears Brown C, & Bigler RS (2005). Children’s perceptions of discrimination: A developmental model. Child development, 76, 533–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Author (2014). Promoting racial literacy in schools: Differences that make a difference. Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- Author, Davis G, & Abdul-Kabir S (2001). Stickin’ to Watchin’ Over, and Gettin’ with: An African American Parent’s Guide to Discipline. Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Author, Reed J, Bodison P, & Bishop A (1997). Racism stress management racial socialization beliefs and the experience of depression and anger in African American youth. Youth & Society, 29, 197–222. [Google Scholar]

- Sue D, Capodilupo C, Torino G, Bucceri J, Holder A, Nadal K, & Esquilin M (2007). Racial microaggressions in everyday life: Implications for clinical practice. American Psychologist, 62, 271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swaine J, Laughland O, Lartey J, McCarthy C (2015) Young black men killed by US police at highest rate in year of 1,134 deaths. The Guardian. Retreived from https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2015/dec/31/the-counted-police-killings-2015-young-black-men.

- The Washington Post. (2017) Fatal Force: Police shootings 2017 database. Retreived from https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/national/police-shootings-2017/

- Thomas AJ, & Blackmon SKM (2015). The influence of the Trayvon Martin shooting on racial socialization practices of African American parents. Journal of Black Psychology, 41, 75–89. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas A, Caldwell C, & DeLoney E (2012). Black like me: The race of African American identity: Racial and cultural. Dimensions of the Black experience. Lexington Books. [Google Scholar]

- Tynes BM, Giang MT, Williams DR, & Thompson GN (2008). Online racial discrimination and psychological adjustment among adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 43, 565–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utsey SO, Chae MH, Brown CF, & Kelly D (2002). Effect of ethnic group membership on ethnic identity, race-related stress and quality of life. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 8, 366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White-Johnson R, Ford K, & Sellers R (2010). Parental racial socialization profiles: Association with demographic factors, racial discrimination, childhood socialization, and racial identity. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 16, 237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West L, Donovan R, & Roemer L (2010). Coping with racism: What works and doesn’t work for Black women? Journal of Black Psychology, 36, 331–349. [Google Scholar]

- Williams J, Tolan P, Durkee M, Francois A, & Anderson R (2012). Integrating racial and ethnic identity research into developmental understanding of adolescents. Child Development Perspectives, 6, 304–311. [Google Scholar]

- Williams MT, Chapman LK, Wong J, & Turkheimer E (2012). The role of ethnic identity in symptoms of anxiety and depression in African Americans. Psychiatry research, 199, 31–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yehuda R, & Bierer L (2009). The relevance of epigenetics to PTSD: Implications for the DSM-V. Journal of traumatic stress, 22, 427–434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]