Abstract

In AML patients, recurrent mutations were shown to persist in remission, however, only some have a prognostic value and persistent mutations might therefore reflect a re-established premalignant state or truly active disease causing relapse. We aimed to dissect the nature of co-mutations in NPM1 mutated AML where the detection of NPM1 transcripts allows highly specific and sensitive detection of complete molecular remission (CMR). We analysed 150 consecutive patients who achieved CMR following intensive treatment by next generation sequencing on paired samples at diagnosis, CMR and relapse (38/150 patients). Patients with persistence or the acquisition of non-DTA (DNMT3A, TET2, ASXL1) mutations at CMR (23/150 patients, 15%) have a significantly worse prognosis (EFS HR = 2.7, p = 0.003; OS HR = 3.6, p = 0.012). Based on clonal evolution analysis of diagnostic, CMR and relapse samples, we redefine pre-malignant mutations and include IDH1, IDH2 and SRSF2 with the DTA genes in this newly defined group. Only the persistence or acquisition of CHOP-like (clonal hematopoiesis of oncogenic potential) mutations was significantly associated with an inferior outcome (EFS HR = 4.5, p = 0.0002; OS HR = 5.5, p = 0.002). Moreover, the detection of CHOP-like mutations at relapse was detrimental (HR = 4.5, p = 0.01). We confirmed these findings in a second independent whole genome sequencing cohort.

Subject terms: Cancer genetics, Cancer genetics

Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is characterized by recurrent genetic aberrations including gene mutations [1]. Using modern next generation sequencing (NGS) techniques, typical recurrent mutations can be detected in up to 90% of all AML patients [2]. Moreover, certain aberrations in genes such as NPM1 can be exploited to detect minimal residual disease (MRD) with a high sensitivity of up to 1 in 106 cells [3]. The increasing availability and sensitivity of NGS applications have driven attempts to further identify molecular markers for MRD detection. Several large studies have shown persistent mutations at morphologic and clinical remission following intensive treatment of AML [4–7]. This raised the hypothesis that these mutations might reflect active leukemia and thus the presence of minimal residual disease. This notion was underscored when the persistence of mutations at remission was associated with relapse [6]. However, it was shown that not all genes have the same impact on prognosis: the persistence at remission of certain mutations in genes such as DNMT3A, TET2 or ASXL1 (DTA) was not associated with a worse outcome [4]. What is more, DTA mutations are also the most prevalent gene mutations defining age related clonal hematopoiesis (ARCH [6, 8, 9]) or clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential (CHIP [10]). ARCH has been characterized as a molecular risk factor for the development of hematopoietic disorders including leukemia [11]. However, the presence of certain mutations in otherwise healthy subjects only confers a low risk for transformation [8, 9]. Effort has been put into the discrimination of CHIP-like mutations and mutations that are associated with oncogenic potential (clonal hematopoiesis of oncogenic potential - CHOP) [12]. Therefore, in some cases, the persistence of mutations at remission could reflect the re-establishment of a pre-leukemic state following induction therapy for AML which might not necessitate further treatment. In other cases, the persistence of malignant mutations at remission could truly reflect active disease and therefore warrant intensified treatment strategies [11]. In this light, the existence of harmless CHIP-like and true driver mutations can be hypothesized. To investigate this hypothesis, we analysed paired samples at diagnosis, CMR and relapse of AML patients with mutated NPM1 (NPM1mut).

Methods

Patients and study design

We performed a retrospective cohort study investigating the prevalence and the spectrum of mutations at diagnosis, CMR and relapse of 150 patients diagnosed with NPM1mut AML between 2005 and 2016 at our institution (cohort 1). Diagnosis was assessed by cytomorphology, immunophenotyping and genetic studies according to WHO criteria. Only patients with de novo AML were considered. We included all patients who achieved CMR definded by the absence of NPM1 transcripts (qPCR ratio 0, sensitivity 0.001%) and excluded patients with a NPM1 negative relapse. An additional cohort of 36 NPM1mut AML patients from the 5000 Genome Project (MLL [13, 14]) was studied by whole genome sequencing (WGS) at diagnosis, CMR and for eight patients at relapse (cohort 2). All patients gave their written informed consent for scientific evaluations. The study was approved by the Internal Review Board and adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients were treated with intensive chemotherapy regimens according to AML standard therapy. The median follow-up of the two cohorts was 3.3 years (range: 0.2–8.7).

Genetic analyses

For all patients the mutational status of NPM1 was studied at diagnosis both by melting curve analysis and NGS. All diagnostic, CMR and relapse samples were studied by NGS with a panel of 63 genes associated with hematological malignancies (Supplementary Methods, online only). Library preparation and variants analysis were performed as previously described ([15] and Supplementary Methods). FLT3-ITD was analysed by gene scan in all patients. Chromosome banding analysis (CBA) was performed according to standard procedures in all patients. For cohort 2, WGS analysis was performed on all diagnostic, CMR and relapse samples as previously described ([14] and Supplementary Methods). We focused our analyses on the protein-coding regions of the genome. We also took advantage of the multiplicity of samples per patient to filter out those variants bearing a VAF close to 50% or 100% across all timepoints, indicating either heterozygous or homozygous germline variants.

Results

Patients’ clinical and molecular characteristics

Between 2005 and 2016, 150 patients with NPM1mut AML who achieved a CMR following intensive treatment were included in this study (for details see Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1, online only). Relapse was diagnosed in 34% of patients (52/150), which is in line with previous reports on NPM1mut AML following CMR [16]. A total of 61/150 patients (41%) received allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplant (allo-HSCT) up-front (n = 34/61, 56%) or after relapse (n = 27/61, 44%) with a median time from diagnosis to transplant of 0.8 years (range: 0.5–1.1). In all these patients, the CMR sample was collected prior to HSCT.

Table 1.

Patients’ clinical and molecular features.

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 73 | 49% |

| Female | 77 | 51% |

| WHO AML subtype | ||

| AML with minimal differentiation | 1 | 1% |

| AML without maturation | 66 | 44% |

| AML with maturation | 40 | 27% |

| Acute myelomonocytic leukemia | 30 | 20% |

| Acute monoblastic/monocytic leukemia | 8 | 5% |

| Pure erythroid leukemia | 2 | 1% |

| NA | 3 | 2% |

| ELN risk classification | ||

| Favorable (no FLT3-ITD, or FLT3-ITD+, ratio <0.5) | 116 | 77% |

| Intermediate (FLT3-IDT+, ratio >0.5) | 31 | 21% |

| NA | 3 | 2% |

| Karyotype | ||

| Normal | 134 | 89% |

| Aberranta | 14 | 9% |

| NA | 2 | 1% |

| Median | Range | |

| Age | 57 | 19–82 |

| Hb | 9 | 4–16 |

| Thrombocytes (x103) | 64 | 7–289 |

| Leukocytes (x103) | 30 | 1–224 |

NA not analyzed.

a3/14 (21%): X/Y loss; 1/14 (7%): del(5q); 2/14 (14%): del(9q); 1/14 (7%): ins(10;4); 1/14 (7%): t(3;10); 1/14 (7%): +21; 1/14 (7%): der(1)t(1;13); 3/14 (21%): +8; 1/14 (7%): complex karyotype.

In NPM1mut AML co-mutations persist at CMR

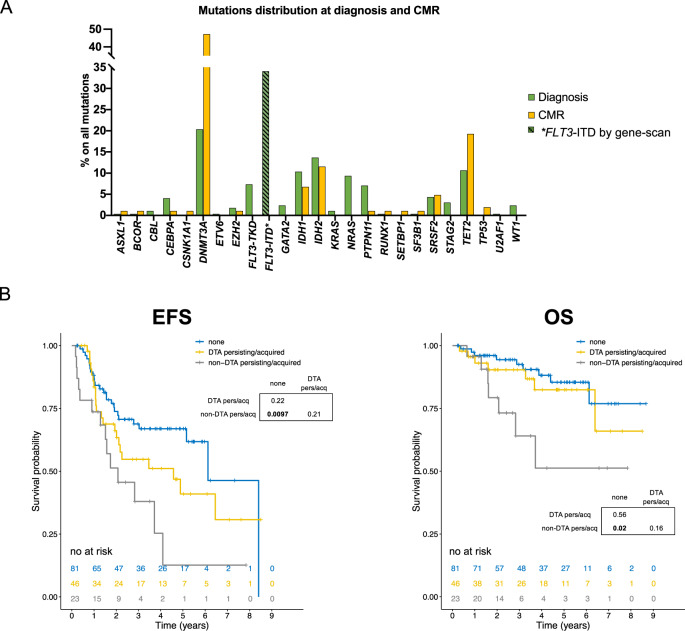

At diagnosis, a total of 301 mutations were detected across all 150 patients, excluding NPM1 (2.1 mutations/patient). Of these, the most common were found in DTA genes DNMT3A (20%) and TET2 (11%) (with the exception of ASXL1 mutations, which is expected given their low frequency in NPM1mut AML [16, 17]), plus others including IDH2 (14%), IDH1 (10%), NRAS (9%), FLT3-TKD (7%), PTPN11 (7%), SRSF2 (4%), and CEBPA (4%) (Fig. 1A). FLT3-ITD was identified in 51/150 patients (34%).

Fig. 1. Persisting/acquired non-DTA mutations at CMR confer inferior survival in AML with mutated NPM1.

A Mutation frequencies of AML associated genes in diagnostic and complete molecular remission (CMR) samples. The percentage of each gene alteration among all the mutations per timepoint is depicted. *FLT3-ITD mutations were detected by gene scan. B Survival analysis of patients with NPM1mut AML stratified by persistence or acquisition of DTA vs non-DTA mutations at CMR. Kaplan–Meier plots depicting event-free survival (EFS left panel) and overall survival (OS right panel) of NPM1mut AML patients based on the combination of persistency and acquisition of non-DTA mutations at CMR. Patients showing non-DTA hits at CMR have a worse prognosis than those who do not. P values were calculated with the log-rank test and p values for pairwise comparisons are given.

At CMR, 69/150 patients carried at least one mutation (46%), using a VAF cutoff of ≥1%, a total of 105 mutations were detected across all 150 patients (0.7 mutations/patient) (Fig. 1A).

This shows that also in NPM1mut AML there is an important fraction of patients displaying mutations at remission, either reflecting MRD positivity or CHIP-like premalignant mutations. No effect of FLT3-ITD on the probability of persistency/acquisition of mutations at CMR was observed (Supplementary Table 2, online only).

Persistence and acquisition of non-DTA mutations at CMR can predict the outcome of NPM1mut AML

Previous work identified that persisting non-DTA mutations at remission are associated with an inferior prognosis [4]. In our cohort 40/150 patients (27%) had persisting DTA mutations and 22/150 (15%) had persisting non-DTA mutations. We confirm that also in the context of NPM1mut AML, patients with persisting non-DTA mutations at CMR had a significantly worse EFS (HR = 2.2, 1.2–4.3, p = 0.01) and OS (HR = 3.9, 1.54–10, p = 0.004) compared to those without persisting mutations (Supplementary Fig. S1A, Supplementary Table 3, online only). We further addressed the acquisition of mutations at remission as a molecular marker for clinical outcome. Patients with at least one novel non-DTA mutation at CMR showed a significantly inferior EFS (HR = 3, 1.3–7.2, p = 0.01) but not OS (HR = 2.8, 0.8–9.7, p = 0.1, Supplementary Fig. S1B, Supplementary Table 3, online only). Incorporating both into a single model we show that patients with either persistent or acquired non-DTA mutations at CMR (n = 23/150, 15%) had a significantly worse prognosis than those who only had persistent/acquired DTA-mutations (n = 46, 31%) or none (n = 81, 54%) (EFS HR = 2.7, 1.4–5.2, p = 0.003; OS HR = 3.6, 1.3–9.8, p = 0.012, Fig. 1B, Supplementary Table 3, online only). We did not observe a survival disadvantage in patients with exclusively persistent DNMT3A-R882 or IDH1/2 mutations at CMR (Supplementary Figs S2A, S2B, online only). Also no impact was observed for ELN risk groups (Supplementary Fig. S2C online only). In a multivariate analysis incorporating allogeneic stem-cell transplantation, aberrant karyotype, gender and age [18] (Supplementary Table 4, online only), the persistency/acquisition of non-DTA mutations at CMR was an independent predictor of outcome (OS HR = 3.8, 1.01–14, p = 0.047).

NPM1 is a second hit mutation on the basis of underlying CHIP

We have previously shown in a cumulative analysis that comparing the VAF of NPM1 with co-mutations, NPM1 was a second hit in the majority of cases [15]. We now analyzed our panel sequencing results for a more accurate assessment of the clonal hierarchy in the diagnostic sample (Supplementary Figs S3A, B online only). As expected, in most of the cases NPM1 was a second hit mutation, with a VAF lower than co-mutated genes including: STAG2, EZH2, DNMT3A, IDH1, IDH2, SRSF2, and TET2.

Moreover, NPM1 as second hit mutation was age dependent and associated with an increased number of acquired and persistent mutations at CMR (Supplementary Fig. S4, online only). These data suggest that NPM1 often drives leukemia on the basis of an underlying CHIP.

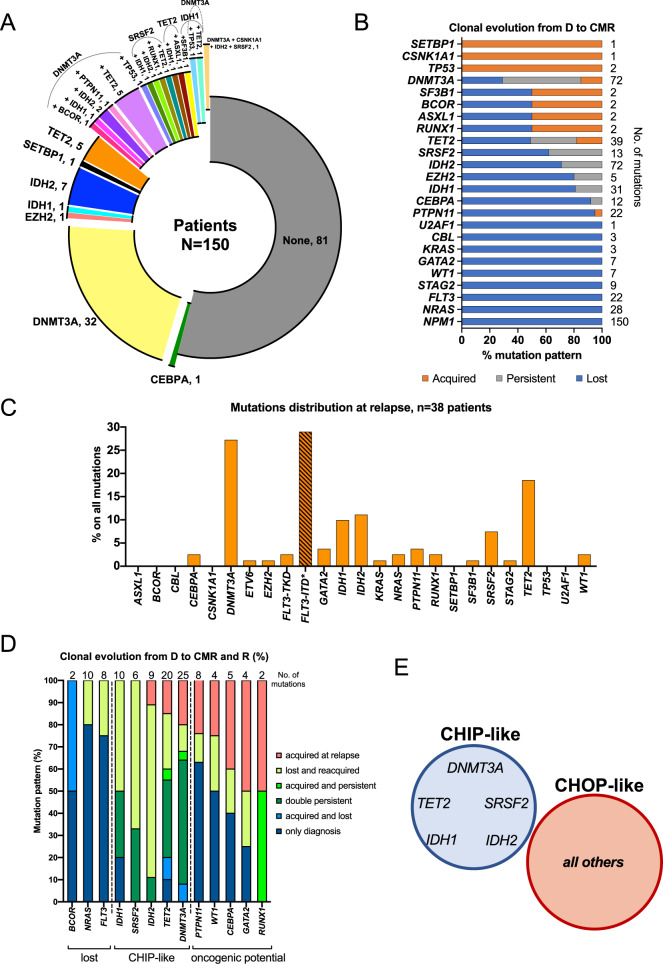

Clonal evolution patterns of NPM1mut AML from diagnosis to CMR and relapse enables classification of co-mutations

In our cohort, 81/150 patients (54%) had no detectable mutation at CMR, whereas 69/150 (46%) showed persistency/acquisition of single or combined mutations, resulting in a total of 24 different groups. Interestingly, persistent DNMT3A, TET2, and SRSF2 mutations possibly define subgroups with similar co-mutational patterns (Fig. 2A). By analyzing the clonal evolution of mutations comparing diagnosis and CMR samples, we identified a group of mutations which were completely or mostly lost, a second group which were almost exclusively acquired at CMR, and a third group with more heterogeneous behavior (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2. Clonal evolution defines persistent CHIP and CHOP-like mutations in NPM1mut AML.

A Donut plot depicting the mutational status of patients at complete molecular remission (CMR). 81/150 patients (54%) had no mutation, whereas 69/150 (46%) had persistency/acquisition of single or combined mutations, for a total of 24 different groups (donut slices). B Clonal evolution analysis of NPM1mut AML from diagnosis to CMR (n = 150 patients). Lost mutations are depicted in blue, persistent mutations in gray and acquired mutations in orange. Three main patterns emerged: mutations that were mostly or completely lost at CMR: NRAS, FLT3-TKD, STAG2, WT1, GATA2, and KRAS (all 100%), PTPN11 (95%), CEBPA (92%), IDH1 (81%), EZH2 (80%), IDH2 (71%); mutations that were mostly or exclusively acquired at CMR (TP53, CSNK1A1 and SETBP1, all 100%), and mutations with a more heterogeneous behavior: SRSF2 (mutation lost in 45% persistent in 38% and acquired in 17% of cases), TET2 (mutation lost in 52%, persistent in 31% and acquired in 17% of cases) and DNMT3A (mutation lost in 29%, persistent in 56% and acquired in 15% of cases). C Mutation frequencies of AML associated genes in relapse samples of 38/52 patients with clinical relapse. The percentage of each gene alteration among all the mutations per timepoint is depicted. *FLT3-ITD mutations were detected by gene scan. D Clonal evolution analysis of NPM1mut AML from diagnosis to CMR and relapse (R) (n = 38 patients) allows for higher temporal resolution and identifies three main patterns: mutations which could either persist at CMR and be lost at R or completely absent at both CMR and R (BCOR, NRAS, FLT3-TKD); CHIP-like mutations present at diagnosis, CMR and R (TET2, IDH1, IDH2, DNMT3A, SRSF2); mutations with oncogenic potential: gained at CMR and persistent at R or acquired de novo at relapse (CEBPA, PTPN11, WT1, GATA2, RUNX1). E DNMT3A, TET2, IDH1, IDH2, and SRSF2 often act as foundation mutations onto which other potentially oncogenic (CHOP) hits arise as later events in AML pathogenesis. Venn diagram showing the novel proposed classification of CHIP-like mutations including: DNMT3A, TET2, IDH1, IDH2, and SRSF2, versus mutations with oncogenic potential (CHOP) in the context of NPM1mut AML.

For 38/52 patients who relapsed, a corresponding sample was available. We detected a total of 84 mutations excluding NPM1 (2.2 mutations/patient). Significantly more patients had detectable co-mutations at relapse than at diagnosis (100% vs 47%, p < 0.0001). As expected, the most common hits were found in DNMT3A (27%), TET2 (19%), IDH2 (11%), IDH1 (10%) and SRSF2 (7%) (Fig. 2C). FLT3-ITD was identified in 11/38 patients (29%) by gene scan.

The analysis of 38 relapse samples allowed a higher temporal resolution and a higher degree of differentiation: focusing on those genes that were mutated in at least 2/38 patients, we establish 3 patterns of clonal evolution (Fig. 2D): mutations which were never present at relapse (BCOR) or often lost at relapse (NRAS, FLT3-TKD); CHIP-like mutations: present at diagnosis, CMR and relapse (TET2, IDH1, IDH2, DNMT3A, SRSF2); mutations with oncogenic potential: gained at CMR and persistent at relapse or acquired de novo at relapse (PTPN11, WT1, CEBPA, GATA2, RUNX1).

Novel definition of CHIP-like vs CHOP-like mutations provides better prognostic stratification in NPM1mut AML

Our analysis shows that next to aberrations in DTA genes, aberrations in SRSF2, IDH2 and IDH1 could act as CHIP-like mutations in NPM1mut AML. This is supported by the clonal hierarchy at diagnosis (Supplementary Figs S3A, B online only). The high number of patient subgroups resulting from the diversity of persistent mutations at CMR (Fig. 2A) abrogates the analysis of their specific outcome. Thus, we implemented a novel classification of CHIP vs CHOP-like mutations in order to identify clinically relevant subpopulations.

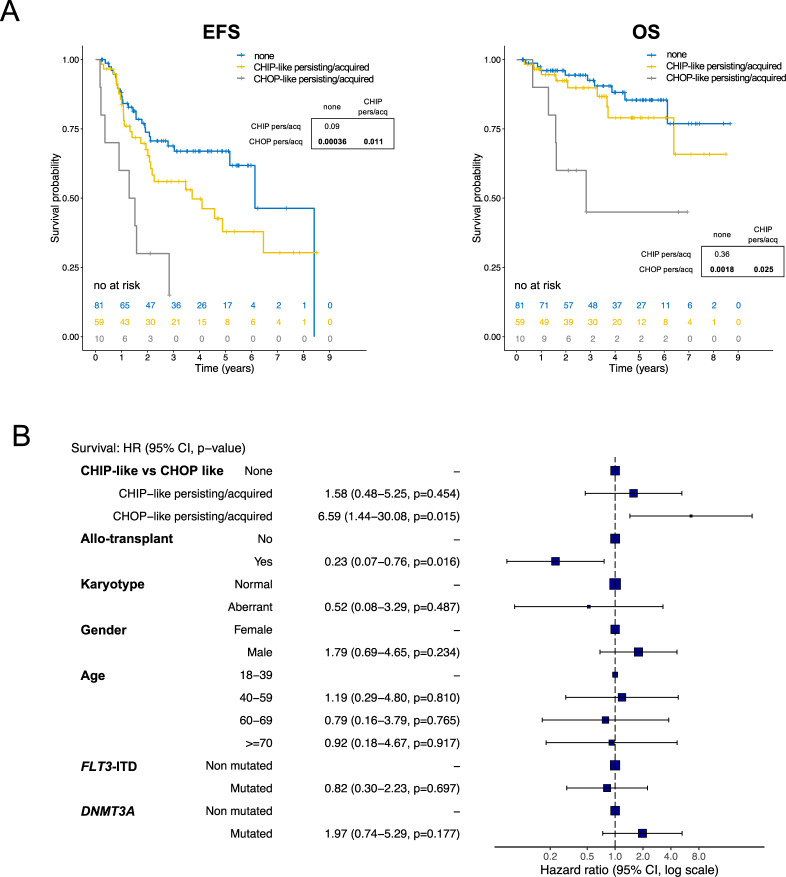

We incorporated DNMT3A, TET2, IDH1, IDH2, and SRSF2 in a single category (namely mutations of indeterminate potential, CHIP-like mutations, Fig. 2D and E) and assessed their impact on survival. As a comparator we used all non-CHIP mutations, which we defined as CHOP-like (mutations of oncogenic potential, Fig. 3A, Supplementary Table 5, online only). Interestingly, this led to a stronger predictive power than the restriction on DTA genes alone: 10 patients (7%) with persistence and/or acquisition of CHOP-like mutations had a significantly inferior outcome compared to those who only had CHIP-like persistent/acquired mutations (n = 59, 39%) or none (n = 81, 54%) (EFS HR = 4.5, 2.0–10.1, p = 0.0002; OS HR = 5.5, 1.8–16.9, p = 0.002). We did not observe a significant effect on survival when focusing on persistent/acquired IDH1/2 and SRSF2 mutations (Supplementary Fig. S5, online only). We finally validated our findings in a multivariate model, incorporating the above-defined factors (Fig. 3B): the persistency/acquisition of CHOP-like mutations at CMR was an independent predictor of outcome (HR = 7, 1.6–30, p = 0.009), and was stronger compared to the previous model (Supplementary Table 4, online only) (HR = 7 vs 3.8; log-rank score: 20.5, vs 14.7; p value: 0.009 vs 0.04). Of note, the presence of CHIP vs CHOP mutations at CMR was not biased by therapeutic regimens administered (Supplementary Fig. S6, online only). In addition, we observed that the detection of co-mutations at diagnosis (CHIP or CHOP) did not have any impact on OS (Supplementary Fig. S7, online only).

Fig. 3. Persistence or acquisition of novel defined premalignant CHIP like mutations vs CHOP like mutations are prognostic in AML with mutated NPM1.

A, B Survival analysis of patients with NPM1mut AML stratified by clonal evolution patterns of novel defined CHIP-like mutations vs oncogenic mutations. Based on the clonal evolution analysis on diagnosis, remission and relapse samples we redefined CHIP-like mutations (DNMT3A, TET2, SRSF2, IDH2, and IDH1) versus all other mutations (CHOP-like). A Kaplan–Meier plots depicting event-free survival (EFS, left panel and OS, right panel) of NPM1mut AML patients based on the persistency/acquisition of CHIP vs CHOP like mutations at CMR. P values were calculated with the log-rank test and p values for pairwise comparisons are given. B Cox proportional hazards multivariate model incorporating clonal evolution patterns by the presence/absence of CHOP-like mutations at CMR, clinical/molecular risk factors and allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. Overall survival (OS) hazard ratio (HR) at 95% confidence interval and p values for each variable are given.

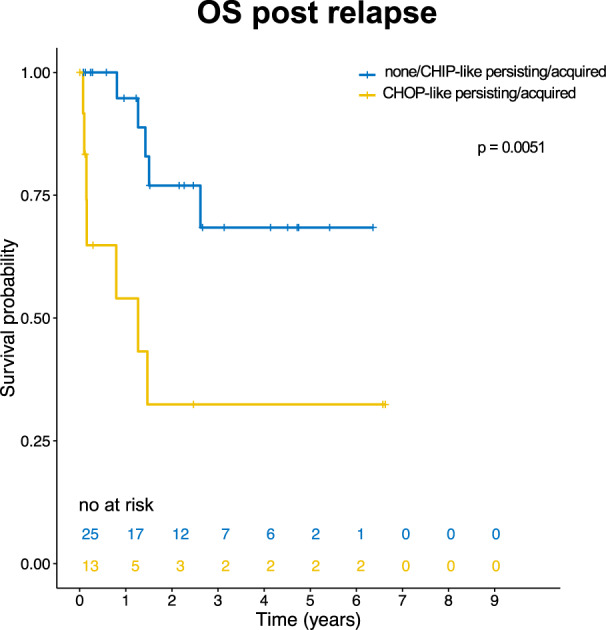

At relapse persistence/acquisition of CHOP-like mutations identifies high risk patients

To our knowledge, our analysis is the first to include mutational screening at relapse in NPM1mut AML following CMR. We were able to analyze 38 patients who experienced clinical relapse (Fig. 2C). We focused on the above-defined group of CHIP-like and CHOP-like mutations (Fig. 2E) and show that 13/38 patients (34%) who had persistent/acquired CHOP-like mutations at relapse had a significantly worse outcome following relapse (HR of death after relapse = 4.5, 1.4–14.3, p = 0.01, Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. CHOP-like persistent or acquired mutations at relapse confer inferior outcome.

Survival analysis of patients with NPM1mut AML experiencing clinical relapse stratified by clonal evolution patterns. Kaplan–Meier plots depicting overall survival (OS) of NPM1mut AML patients following relapse all analysed by panel sequencing (n = 38). We stratified patients that acquired oncogenic mutations at relapse vs patients with no novel or only novel CHIP-like mutations at relapse. OS after relapse was calculated from the date of relapse until the date of death or censoring. P values were calculated with the log-rank test.

Independent WGS cohort confirms the clinical impact of persisting CHOP-like mutations

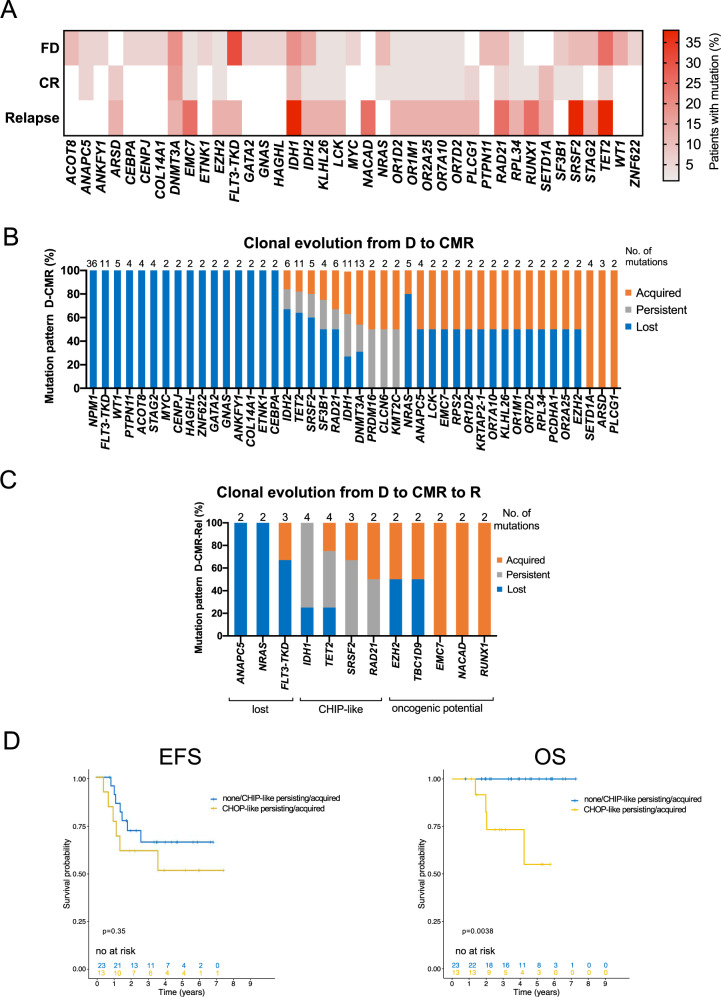

We were able to analyze data from an additional 36 NPM1mut AML patients which were sequenced both at diagnosis and complete remission by WGS as part of the MLL 5000 genomes project [13, 14]. Eight of them (22%) experienced a clinical and molecular progression (NPM1mut) and we sequenced the relapse samples by WGS. Clinical characteristics of this cohort are given in Supplementary Table 6 (Supplementary Table 6, online only).

For a comparison with the panel sequencing cohort, we focused our analysis on small variants found across the coding regions. At diagnosis, a total of 362 mutations were found across all 36 patients, including NPM1 (10.1 mutations/patient, Fig. 5A). We observed mutations in several genes not known to be associated with AML, including: ACOT8, ANAPC5, ANKFYI, CENPJ, COL14A1, ETNK1, GNAS, HAGHL, and ZNF622.

Fig. 5. Mutational analysis of independent WGS cohort recapitulates the panel-seq findings and confirms predictive power of CHOP-like mutations.

A Mutation frequencies of AML associated genes in diagnostic (D), complete molecular remission (CMR) and relapse samples (R). Mutations detected in at least two patients are depicted. B Clonal evolution analysis of NPM1mut AML from diagnosis to CMR (n = 36 patients) of genes mutated in at least two patients. Lost mutations are depicted in blue, persistent mutations in gray and acquired mutations in orange. C Clonal evolution analysis of NPM1mut AML from D to CMR and R (n = 8 patients) allows for higher temporal resolution and identifies three main patterns: mutations which could either persist at CMR and be lost at R or completely absent at both CMR and R (ANAPC5, NRAS, FLT3-TKD); CHIP-like mutations present at D, CMR and R (TET2, IDH1, SRSF2); mutations with oncogenic potential: gained at CMR and persistent at R or acquired de novo at R (RAD21, TBC1D9, EZH2, EMC7, NACAD, RUNX1); D Survival analysis of 36 patients from the WGS cohort stratified by clonal evolution patterns of novel defined CHIP-like mutations (DNMT3A, TET2, ASXL1, SRSF2, IDH1, IDH2): Kaplan–Meier plots depicting event-free survival (EFS, left panel) and overall survival (OS, right panel) of NPM1mut AML patients based on the persistency/acquisition of CHIP vs CHOP like mutations at CMR. P values were calculated with the log-rank test.

At CMR, we detected a total of 138 mutations (3.8 mutations/patient, Fig. 5A). Again we observed mutations not previously associated with AML: SETD1A, ARSD, ANAPC5, PLCG1. Out of those all but 2 mutations in ANAPC5 were not detected in the diagnostic sample.

In the eight patients with relapse, a total of 85 mutations was found (10.6 mutations/patient, Fig. 5A). The most common expected mutations were detected in: IDH1, TET2, SRSF2, RAD21, RUNX1. Unexpected mutations were detected in EMC7 and NACAD.

The clonal evolution analysis of diagnostic and remission samples on all 36 patients identified a group of mutations which were completely or mostly lost and a second group which were almost exclusively acquired at CMR, indicating mutations with oncogenic potential. A third group showed a heterogeneous behavior that could identify CHIP-like mutations (Fig. 5B).

Focusing on the eight patients with available relapse samples, we identified three clonal evolution patterns: mutations mainly lost at CMR or relapse, mutations persistent at CMR or relapse (CHIP-like) and mutations gained at CMR and relapse (CHOP-like). This confirms the patterns found in the panel sequencing cohort (Fig. 5C).

Finally, we analyzed survival on this independent cohort using the above stratification based on persistency/acquisition of CHIP/CHOP-like mutations (Fig. 5D). Although this analysis was limited by the cohort size and the few events, we observed that patients with at least one persistent/acquired CHOP-like mutation at CMR showed a significantly poorer OS than those who did not (HR = 10.4, 1.2–86.6, p = 0.03).

Discussion

In this report we selected a uniform cohort of 150 NPM1mut AML patients all achieving CMR, and redefined the potential role of co-mutations persistent at remission. We identified the persistence of non DTA-mutations at CMR in a significant proportion of patients (15%), and confirm previous studies showing that the persistence of non-DTA-mutations in remission is detrimental [4, 6, 7]. However, those reports were focused on a variety of unselected AML. We have now addressed this phenomenon in the well-defined context of CMR in NPM1mut AML. For this entity, MRD detection in clinical remission has long been established and is more informative for survival than the detection of co-mutations such as FLT3-ITD or DNMT3A [16, 19]. Our data on NPM1mut AML in CMR suggest that the persistence of non-DTA mutations represents molecular residual disease. Furthermore, we show for the first time that also the acquisition of non-DTA mutations at CMR is an adverse prognostic factor in NPM1mut AML.

The mutation diversity at CMR does not allow to reasonably address impact of single hits on survival even in our relatively large cohort, as we identified 24 different sub-cohorts according to persistent/acquired mutations. We therefore aimed to classify those mutations in favorable and adverse mutations. This is in line with recent efforts differentiating CHIP-like mutations from mutations with oncogenic potential [12, 20], termed CHOP-like mutations. Our analysis makes use of clonal hierarchy at diagnosis and the clonal evolution of co-mutations in CMR and relapse to classify mutations into those categories. We excluded patients with NPM1 negative relapse to reduce the likelihood of secondary or t-AML [15]. The group of CHIP-associated mutations was extended to include mutations in DNMT3A, TET2, IDH1, IDH2, and SRSF2. All those mutations had a CHIP-like pattern in our analysis. This was further justified by the fact that also persistent/acquired IDH1/2 or SRSF2 mutations had no impact on survival along with mutations in DNMT3A and TET2. ASXL1 mutations are a rare event in NPM1mut AML and were not included in this group [16, 17]. We defined all other mutations (i.e., FLT3-TKD, GATA2, NRAS, PTPN11, WT1, TP53, RUNX1) as CHOP-like. Those were usually acquired at CMR and acquired/persistent at relapse. We prove a strong prognostic value of persistent and/or acquired CHOP-like mutations at CMR, in contrast to CHIP-like mutations. On the other hand, the detection of either CHIP or CHOP mutations at diagnosis did not have any impact on OS, highlighting the importance of sampling at CMR. Our data therefore allows the distinction of molecular residual disease from the persistence of a pre-malignant state which likely does not affect prognosis. We propose a model where CHIP-like mutations define a pre-malignant state in NPM1mut AML, and the transformation to full AML is caused by the additional acquisition of driver mutations. This is backed by previous reports suggesting that NPM1 mutation is a late event in leukemogenesis [15, 17, 21].

We confirm that the persistence of DNMT3A-R882 mutations is not associated with inferior survival [22]. However, contrasting earlier reports [23–25], also persistent IDH1/2 mutations were not associated with survival. We only identified eight patients with the exclusive persistence of IDH mutations, which did not show a dismal outcome. In other studies, adverse co-mutations accompanying IDH1/2, i.e., CHOP-like mutations, were not analyzed but could have been responsible for the inferior outcome.

We make use of a second cohort analyzed by WGS, focusing on the detection of small variants across the whole coding region. Albeit smaller, this cohort supports the definition of CHIP-like and CHOP-like mutations and the role of persistent/acquired CHOP-like mutations on outcome.

One could argue that different treatment strategies could perform better in eradicating molecular disease. In our analysis different inductions regimens did not have any impact on the distribution of CHIP/CHOP mutations at CMR.

CMR in NPM1mut AML is an independent factor for good risk disease [16], however up to 30% of patients with CMR relapse. Here we provide a clinical tool where the detection of oncogenic mutations at CMR, acquired or persistent, is an independent prognostic factor facilitating early intervention in those patients. Studies with MRD guided therapy in AML show promising results: in the RELAZA2 trial, patients with MRD positive AML following conventional chemotherapy or allogeneic transplant were treated with azacytidine and showed a clinical meaningful benefit [26]. Based on the QUAZAR trial an oral formulation of azacytidine (CC-486) is the first approved maintenance therapy for AML [27], which could be especially worthy in patients with persistent CHOP-like mutations.

We also showed that patients relapsing with persistent or novel CHOP-like mutations have an inferior prognosis. Those patients represent an unmet clinical need and strategies like the RELAZA protocol, maintenance with demethylating substances [26, 28] or treatment with novel agents [29] could improve outcome.

In conclusion, our data show that even in the relatively favorable context of NPM1mut AML following CMR, modern NGS based screening can identify patients at risk in order to develop personalized therapeutic strategies aimed at eradicating MRD and molecular residual disease to prevent relapse. The conduction of NGS-based MRD-guided clinical trials dedicated to this subset of NPM1mut AML patients is highly warranted.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank all patients and clinicians for their participation in this study and all co-workers in our laboratory for their excellent technical assistance.

Author contributions

AH and CH designed the study. LVC and AH interpreted the data and wrote the paper. MM, CB, NN, SJ and FD did molecular analyses. SH helped with statistical analysis. TH was responsible for cytomorphologic analyses, CH for cytogenetic and FISH analyses and WK for immunophenotyping. All authors read and contributed to the final version of the paper.

Funding

Luca Vincenzo Cappelli received a grant by the “Torsten Haferlach Leukämiediagnostikstiftung”.

Data sharing statement

Sequencing data was deposited at NCBI, accession number PRJNA745264.

Competing interests

MM, CB, NN, SH, SJ and FD: Employment by MLL Munich Leukemia Laboratory; LVC: grant by Torsten Haferlach Leukämiediagnostikstiftung. CH, WK, TH: Equity ownership of MLL Munich Leukemia Laboratory. AH: no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41375-021-01368-1.

References

- 1.DiNardo CD, Cortes JE. Mutations in AML: prognostic and therapeutic implications. Hematol Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2016;2016:348–55. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2016.1.348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Papaemmanuil E, Gerstung M, Bullinger L, Gaidzik VI, Paschka P, Roberts ND, et al. Genomic classification and prognosis in acute myeloid leukemia. N. Engl J Med. 2016;374:2209–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1516192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ravandi F, Walter RB, Freeman SD. Evaluating measurable residual disease in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood Adv. 2018;2:1356–66. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2018016378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jongen-Lavrencic M, Grob T, Hanekamp D, Kavelaars FG, Al HA, Zeilemaker A, et al. Molecular minimal residual disease in acute myeloid leukemia. N. Engl J Med. 2018;378:1189–99. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1716863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klco JM, Miller CA, Griffith M, Petti A, Spencer DH, Ketkar-Kulkarni S, et al. Association between mutation clearance after induction therapy and outcomes in acute myeloid leukemia. JAMA. 2015;314:811–22. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.9643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rothenberg-Thurley M, Amler S, Goerlich D, Köhnke T, Konstandin NP, Schneider S, et al. Persistence of pre-leukemic clones during first remission and risk of relapse in acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2018;32:1598–608. doi: 10.1038/s41375-018-0034-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morita K, Kantarjian HM, Wang F, Yan Y, Bueso-Ramos C, Sasaki K, et al. Clearance of somatic mutations at remission and the risk of relapse in acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol: Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2018;36:1788–97. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.77.6757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jaiswal S, Fontanillas P, Flannick J, Manning A, Grauman PV, Mar BG, et al. Age-related clonal hematopoiesis associated with adverse outcomes. N. Engl J Med. 2014;371:2488–98. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1408617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Genovese G, Kahler AK, Handsaker RE, Lindberg J, Rose SA, Bakhoum SF, et al. Clonal hematopoiesis and blood-cancer risk inferred from blood DNA sequence. N. Engl J Med. 2014;371:2477–87. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1409405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steensma DP, Bejar R, Jaiswal S, Lindsley RC, Sekeres MA, Hasserjian RP, et al. Clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential and its distinction from myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood. 2015;126:9–16. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-03-631747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abelson S, Collord G, Ng SWK, Weissbrod O, Mendelson Cohen N, Niemeyer E, et al. Prediction of acute myeloid leukaemia risk in healthy individuals. Nature. 2018;559:400–4. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0317-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Valent P, Akin C, Arock M, Bock C, George TI, Galli SJ, et al. Proposed terminology and classification of pre-malignant neoplastic conditions: a consensus proposal. EBioMedicine. 2017;26:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2017.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parida L, Haferlach C, Rhrissorrakrai K, Utro F, Levovitz C, Kern W, et al. Dark-matter matters: discriminating subtle blood cancers using the darkest DNA. PLoS Comput Biol. 2019;15:e1007332. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1007332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hollein A, Twardziok SO, Walter W, Hutter S, Baer C, Hernandez-Sanchez JM, et al. The combination of WGS and RNA-Seq is superior to conventional diagnostic tests in multiple myeloma: ready for prime time? Cancer Genet. 2020;242:15–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergen.2020.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hollein A, Meggendorfer M, Dicker F, Jeromin S, Nadarajah N, Kern W, et al. NPM1 mutated AML can relapse with wild-type NPM1: persistent clonal hematopoiesis can drive relapse. Blood Adv. 2018;2:3118–25. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2018023432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ivey A, Hills RK, Simpson MA, Jovanovic JV, Gilkes A, Grech A, et al. Assessment of minimal residual disease in standard-risk AML. N. Engl J Med. 2016;374:422–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1507471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cappelli LV, Meggendorfer M, Dicker F, Jeromin S, Hutter S, Kern W, et al. DNMT3A mutations are over-represented in young adults with NPM1 mutated AML and prompt a distinct co-mutational pattern. Leukemia. 2019;33:2741–6. doi: 10.1038/s41375-019-0502-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Acharya UH, Halpern AB, Wu QV, Voutsinas JM, Walter RB, Yun S, et al. Impact of region of diagnosis, ethnicity, age, and gender on survival in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) J Drug Assess. 2018;7:51–3. doi: 10.1080/21556660.2018.1492925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schnittger S, Kern W, Tschulik C, Weiss T, Dicker F, Falini B, et al. Minimal residual disease levels assessed by NPM1 mutation-specific RQ-PCR provide important prognostic information in AML. Blood. 2009;114:2220–31. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-213389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Valent P, Kern W, Hoermann G, Milosevic Feenstra JD, Sotlar K, Pfeilstocker M, et al. Clonal hematopoiesis with oncogenic potential (CHOP): separation from CHIP and roads to AML. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Patel JL, Schumacher JA, Frizzell K, Sorrells S, Shen W, Clayton A, et al. Coexisting and cooperating mutations in NPM1-mutated acute myeloid leukemia. Leuk Res. 2017;56:7–12. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2017.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bhatnagar B, Eisfeld AK, Nicolet D, Mrozek K, Blachly JS, Orwick S, et al. Persistence of DNMT3A R882 mutations during remission does not adversely affect outcomes of patients with acute myeloid leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2016;175:226–36. doi: 10.1111/bjh.14254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ok CY, Loghavi S, Sui D, Wei P, Kanagal-Shamanna R, Yin CC, et al. Persistent IDH1/2 mutations in remission can predict relapse in patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Haematologica. 2019;104:305–11. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2018.191148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferret Y, Boissel N, Helevaut N, Madic J, Nibourel O, Marceau-Renaut A, et al. Clinical relevance of IDH1/2 mutant allele burden during follow-up in acute myeloid leukemia. A study by the French ALFA group. Haematologica. 2018;103:822–9. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2017.183525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Debarri H, Lebon D, Roumier C, Cheok M, Marceau-Renaut A, Nibourel O, et al. IDH1/2 but not DNMT3A mutations are suitable targets for minimal residual disease monitoring in acute myeloid leukemia patients: a study by the Acute Leukemia French Association. Oncotarget. 2015;6:42345–53. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Platzbecker U, Middeke JM, Sockel K, Herbst R, Wolf D, Baldus CD, et al. Measurable residual disease-guided treatment with azacitidine to prevent haematological relapse in patients with myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myeloid leukaemia (RELAZA2): an open-label, multicentre, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:1668–79. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30580-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wei AH, Döhner H, Pocock C, Montesinos P, Afanasyev B, Dombret H, et al. Oral azacitidine maintenance therapy for acute myeloid leukemia in first remission. N. Engl J Med. 2020;383:2526–37. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2004444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huls G, Chitu DA, Havelange V, Jongen-Lavrencic M, van de Loosdrecht AA, Biemond BJ, et al. Azacitidine maintenance after intensive chemotherapy improves DFS in older AML patients. Blood. 2019;133:1457–64. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-10-879866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cortes JE, Heidel FH, Hellmann A, Fiedler W, Smith BD, Robak T, et al. Randomized comparison of low dose cytarabine with or without glasdegib in patients with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia or high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome. Leukemia. 2019;33:379–89. doi: 10.1038/s41375-018-0312-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Sequencing data was deposited at NCBI, accession number PRJNA745264.