Abstract

Two cases of culture-negative endocarditis with cocci seen in valve vegetations are presented. The organisms were identified by molecular analysis using broad-range PCR primers complementary to the 16S rRNA gene, sequencing, and database search using BLAST software. The results and utility of this method are discussed.

CASE REPORTS

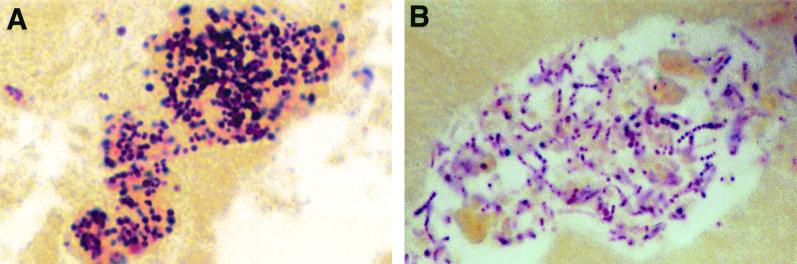

Patient 1 is a 36-year-old woman who was seen in the emergency department with fever, intermittent chills, left-sided pleuritic chest pain, and hemoptysis. She was a known intravenous drug abuser and had been discharged from the hospital 2 weeks previously after a 6-week course of antibiotics for methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus endocarditis of the tricuspid valve. Cardiovascular examination was consistent with recurrent endocarditis, and a transesophageal echocardiogram confirmed persistent tricuspid valve vegetations. Blood cultures were negative. Due to clinical evidence of pulmonary emboli and worsening cardiovascular status, she was taken to the operating room. A 2.0-diameter cm tricuspid valve vegetation was removed. Brown and Brenn staining of the vegetation revealed gram-positive cocci in clusters (Fig. 1A). However, culture of the vegetation in Fildes-enriched thioglycolate broth, remained negative.

FIG. 1.

Brown and Brenn stain of the valve vegetations for patient 1 (A) and patient 2 (B). Gram-positive cocci were seen in both specimens. Magnification, ×400.

Patient 2 is a 46-year-old, active intravenous drug abuser who was admitted with increasing shortness of breath, fever, and systolic and diastolic murmurs at the left sternal border. He had recently been admitted to an outlying hospital for community-acquired pneumonia and was treated with parenteral, followed by oral, antibiotics. The course of oral antibiotics was completed 1 week prior to his index presentation when he was readmitted to the hospital with the initial diagnosis of incompletely treated pneumonia. He was then started on trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Once it was clinically evident that he had endocarditis, his antimicrobials were changed to vancomycin, rifampin, and gentamicin, and he was transferred for further care. A transesophageal echocardiogram revealed pulmonic valve vegetations and confirmed the clinical diagnosis of infective endocarditis. All blood cultures at both hospitals were negative. The patient deteriorated despite parenteral antibiotics, and he underwent valvular replacement on hospital day 8. Brown and Brenn staining of the resected valve revealed gram-positive cocci in chains (Fig. 1B). Culture of the valve vegetation in Fildes-enriched thioglycolate broth remained negative.

These cases presented concurrently at our hospital and posed similar problems. Both had previous exposure to antibiotics and now presented with culture-negative endocarditis requiring surgical management. Despite progressive endocarditis and the observation of organisms in the valve vegetations, both blood and valve remained culture negative. Prolonged prior antibiotic coverage, rendering the culture sterile, or an unusually fastidious organism could account for these findings. The patient histories and the findings of Brown and Brenn staining suggested the former.

To identify the organisms seen in the paraffin-embedded pathology tissue, molecular analysis including deparaffinization, DNA extraction, PCR, and sequencing of a portion of the 16S rRNA gene was performed. This method has been applied to both general culture-negative infections (6) and, more specifically, to endocarditis (2, 4), usually in the research setting.

Paraffin-embedded tissue specimens were aseptically obtained from the valve vegetations by the Department of Surgical Pathology. These then underwent xylene-ethanol deparaffinization. The Staphylococcus aureus originally isolated from patient 1's blood during her previous episode of endocarditis had, at the time of isolation, been stored by the Clinical Microbiology Laboratory and was available for comparative purposes. This Staphylococcus aureus was recultured from the Cystine Trypticase Agar on which it had been stored and was phenotypically reidentified, and 2 to 3 CFU were further processed. A known American Type Culture Collection Staphylococcus aureus strain and a known Escherichia coli were used as controls.

Tissue digestion and DNA extraction were performed using the Invitrogen (Carlsbad, Calif.) Easy-DNA kit. The universal prokaryotic primers, forward primer p11 (5′-GAGGAAGGTGGGGATGACGT-3′) and reverse primer p13 (5′-AGGCCCGGGAACGTATTCAC-3′) (1, 8), were chosen to amplify a 215-bp segment containing the 16S rRNA DNA sequences between E. coli nucleotide positions 1175 and 1390 (1, 8). For each sample, we used 60 μl of PCR mixture. This contained 6 μl of 10× PCR buffer; 1.5 mM MgCl2; 167 μM concentrations of dATP, dCTP, dGTP, and dUTP; 2.5 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Roche, Indianapolis, Ind.); 0.15 μM concentrations of p11 and p13 primers (Operon, Alameda, Calif.); and 200 to 300 ng of DNA.

We column purified the PCR products using a Qiaquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen, Valencia, Calif.). Sequence analysis was carried out on an Applied biosystem 377 gel DNA Sequencer at the HHMI Biopolymer/W. M. Keck Foundation Biotechnology Resource Laboratory at the Yale University School of Medicine using the p11 primer. The sequencing reactions utilized fluorescence-labeled dideoxynucleotides (Big Dye Terminators) and Taq FS DNA polymerase in a thermal-cycling protocol (Perkin-Elmer, Foster City, Calif.). The DNA sequences of approximately 182 to 185 bases, exclusive of primers, were compared to all bacterial sequences available in the GenBank, EMBL, and DDBJ databases by using the BLAST 2.0 program (National Center for Biotechnology Information).

Our results were as follows. The sequence of the organism sampled from patient 1's valve showed 100% homology with Staphylococcus aureus (three 100% homologous Staphylococcus aureus sequences were identified) and Staphylococcus intermedius (two 100% homologous Staphylococcus intermedius sequences were identified). In addition, there was 100% homology between the bacterial DNA isolated from patient 1's vegetations to that extracted from the Staphylococcus aureus isolated from her blood during her prior admission.

DNA sequencing of the 187-base PCR product isolated from patient 2's vegetations showed 100% homology with Streptococcus thermophilus and one base difference with Streptococcus salivarius. Further results included human oral bacterium C23, with a match of 185 of 187 bases; Streptococcus bovis, with a match of 184 of 187 bases; and Streptococcus infantarius, with a match of 183 of 187 bases.

With increased use of broad-spectrum and/or extended-spectrum antibiotic therapy, the above culture-negative infection case scenarios are increasingly common. They represent the “ideal” indication for PCR in the clinical laboratory, as suggested by Rantakokko-Jalava et al. (6).

The homology of the bacterial DNA from patient 1's vegetation to both Staphylococcus intermedius and Staphylococcus aureus stems from the similarity between these two organisms. Both are coagulase positive, a principle diagnostic feature of Staphylococcus aureus, and have many phenotypic similarities (10). Comparison of the 16S rRNA DNA of these two organisms, using the BLAST 2.0 program, reveals a 95% homology. Staphylococcus intermedius is rarely isolated in humans and is most commonly found in the mouth and on the skin of canines (3, 9). The results from patient 1's vegetation are highly suggestive of Staphylococcus aureus endocarditis. The 100% homology to the organism isolated from her blood several weeks before suggests that her second episode of endocarditis may have been the result of treatment failure with persistence of the original Staphylococcus strain. The 16S rRNA gene is well conserved and thus should not be used to identify clonality among Staphylococcus aureus isolates. Therefore, we cannot eliminate the possibility that the second infection was caused by a new strain of Staphylococcus aureus.

Patient 2's result also pointed to two closely related organisms. When grouping the streptococcal species according to 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis, Streptococcus thermophilus falls in the Streptococcus salivarius group of viridans group streptococci (5). This group also includes Streptococcus salivarius and Streptococcus vestibularis. Streptococcus salivarius is a well-recognized cause of bacterial endocarditis. Identifying the causative organism as one within the Streptococcus salivarius group has important epidemiological and treatment implications.

Some factors need to be considered before the organisms are identified by this method. For example, the GenBank, EMBL, and DDBJ databases are public databases that are not peer reviewed and contain human, animal, and environmental organisms, both pathogenic and nonpathogenic. Peer-reviewed databases for defining the 16S rRNA sequences of bacteria found in humans would improve the validity of this method of organism identification in the clinical microbiology laboratory. Furthermore, the similarity between sequences of different species and genomes, with important phenotypic differences, makes interpretation more complex. The sequence lengths used were short and did not allow clear differentiation between similar genomes of Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus intermedius, and Streptococcus salivarius and Streptococcus thermophilus. By sequencing larger 16S rRNA gene fragments, more definitive differentiation between these organisms may have been possible. Because of the close similarity in DNA sequence between some bacterial species, any sequencing errors would greatly hinder interpretation; therefore, bidirectional sequencing could be performed to improve DNA sequencing accuracy.

The material costs, excluding labor, amounted to $59.00 per specimen (this included the deparaffinization and DNA extraction from the surgical specimen, materials for PCR, PCR cleanup, sequencing, and the processing of a control). When considering the costs of empiric, broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics and multiple investigations done in the diagnostic workup, these costs are modest for the information provided.

In conclusion, PCR and sequencing, originally confined to research laboratories, has clear benefits in the clinical laboratory. Amplification and sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene as an aid in diagnosis of culture-negative infections will have a positive impact on patient care and cost-effective treatment.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the help of the Yale-New Haven Hospital, Department of Surgical Pathology, for the DNA extraction performed on the surgical specimens.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chen K, Neimark H, Rumore P, Steinman C R. Broad-range DNA probes for detecting and amplifying eubacterial nucleic acids. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1989;57:19–24. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(89)90139-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldenberger D, Künzli A, Vogt P, Zbinden R, Altwegg M. Molecular diagnosis of bacterial endocarditis by broad-range PCR amplification and direct sequencing. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2733–2739. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.11.2733-2739.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hajek V. Staphylococcus intermedius, a new species isolated from animals. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1976;26:401–408. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jalava J, Kotilainen P, Nikkari S, Skurnik M, Vänttinen E, Lehtonen O P, Eerola E, Toivanen P. Use of the polymerase chain reaction and DNA sequencing for detection of Bartonella quintana in the aortic valve of a patient with culture-negative infective endocarditis. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21:891–896. doi: 10.1093/clinids/21.4.891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koneman E W, Allen S D, Janda W M, Schreckenberger P C, Winn W C. The “family Streptococcaceae”: taxonomy and clinical significance. In: Koneman E W, Allen S D, Janda W M, Schreckenberger P C, Winn W C, editors. Color atlas and textbook of diagnostic microbiology. 5th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins Publishers; 1997. p. 581. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rantakokko-Jalava K, Nikkari S, Jalava J, Eerola E, Skurnik M, Meurman O, Ruuskanen O, Alanen A, Kotilainen E, Toivanen P, Kotilainen P. Direct amplification of rRNA genes in diagnosis of bacterial infections. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:32–39. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.1.32-39.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Relman D A. Universal bacterial 16S rRNA amplification and sequencing. In: Persing D H, Smith T F, Tenover F C, White T J, editors. Diagnostic molecular microbiology: principles and applications. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1993. p. 489. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Relman D A, Loutit J S, Schmidt T M, Falkow S, Tompkins L S. The agent of bacillary angiomatosis. An approach to the identification of uncultured pathogens. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:1573–1580. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199012063232301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tanner M A, Everett C L, Youvan D C. Molecular phylogenetic evidence for noninvasive zoonotic transmission of Staphylococcus intermedius from a canine pet to a human. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:1628–1631. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.4.1628-1631.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van der Zee A, Verbakel H, van Zon J C, Frenay I, van Belkum A, Peeters M, Buiting A, Bergmans A. Molecular genotyping of Staphylococcus aureus strains: comparison of repetitive element sequence-based PCR with various typing methods and isolation of a novel epidemicity marker. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:342–349. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.2.342-349.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]