Abstract

We report the first case of Mycobacterium lentiflavum disseminated infection in a human immunodeficiency virus-infected patient. Conventional identification procedures failed to identify the mycobacterial strain, but sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene led to the species identification. Furthermore, we describe here the analysis of the 16S-23S rRNA internal transcribed spacer sequence of M. lentiflavum.

CASE REPORT

The patient was a 49-year-old, homosexual male with known human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) seropositivity since 1989. In October 1996, he was hospitalized in the Department of Internal Medicine and Infectious Diseases with fever, cough, shortness of breath, and weight loss. The CD4 count was 40/mm3, and HIV RNA levels were 33,000 copies/ml. A chest computed tomography scan revealed an interstitial syndrome. Three blood samples for culture were collected on Septi-Chek AFB medium (Roche Diagnostic Systems), and a bronchoalveolar lavage fluid sample was inoculated onto Löwenstein-Jensen and Colestsos medium slants. After 4 weeks, all the sample cultures grew acid-fast, rod-shaped coccobacilli, subsequently identified as Mycobacterium lentiflavum. The blood sample isolate, named HL1, was found to be susceptible to clarithromycin (MIC, 1 μg/ml) and rifabutin (MIC, 0.12 μg/ml).

Chemotherapy with three drugs, clarithromycin, rifabutin, and ethambutol, was started. After 4 months of such therapy and the introduction of a new antiretroviral regimen with two nucleoside analogs and a protease inhibitor, the patient improved clinically and fully recovered for several months. Three blood cultures performed at 3, 6, and 9 months of treatment remained negative. The patient died 3 years later of cardiac failure.

Microbiological investigation.

Colonies of strain HL1 on Löwenstein-Jensen medium were smooth and 1 to 2 mm in diameter and showed bright yellow pigmentation with a colony morphology similar to that of M. avium. Subculture of the isolate showed growth in 4 weeks at 22 and 37°C. For all isolates, conventional identification methods (4) showed negative tests for nicotinic acid production, Tween 80 hydrolysis, nitrate reductase, urease, and heat-stable catalase. On the basis of the enzymatic activities the isolate was most closely related to M. avium, but a negative result with a DNA probe for M. avium complex (Accuprobe; GenProbe) eliminated this hypothesis. In comparison to other slowly growing strains of mycobacteria, this isolate could be distinguished from M. genavense by its ability to grow on standard mycobacterial solid media (2). The lack of urease and the yellow pigmentation eliminated M. simiae (12), M. malmoense (12), and M. triplex (6).

Because of a lack of results by conventional testing, different nucleic acid analyses were performed with the DNA of the HL1 clinical strain. They included PCR-restriction enzyme pattern analysis (PRA) of the hsp65 gene (1), PCR amplification, and sequencing analysis of the 16S rRNA gene (9) and of the 16S-23S rRNA gene internal transcribed spacer region (ITS) (11). The sequences obtained were compared to known 16S rRNA and ITS sequences available in GenBank by pairwise and multiple-sequence alignments with LALIGN (Infobiogen), CLUSTALW (Infobiogen), and BLAST (National Center for Biotechnology Information) software.

The PRA pattern, based on the results obtained by digestion with both BstEII and HaeIII enzymes, showed two fragments of 150 and 135 bp with HaeIII but no restriction site with BstEII. This pattern was compatible with the PRA results previously described for M. lentiflavum and differed from those described for M. simiae (12), M. genavense (12), and M. malmoense (1). The 482-bp 16S rRNA fragment sequenced from isolate HL1 showed 100% identity with the sequence of the M. lentiflavum reference strain (12). Homologies with the 16S rRNA sequences of M. simiae (10) and M. triplex (6), M. genavense (2), and M. malmoense (10) were lower, with 98, 97, and 93.7% identities, respectively.

In the sequence comparison with the BLAST software, the best homologies found for the 283-bp ITS PCR fragment of isolate HL1 were with the ITS sequences of M. triplex (11), M. genavense (11), and M. simiae (8). It should be noted that the 16S–23S rRNA gene ITS sequence of M. lentiflavum was not available in the sequence libraries. Therefore, we amplified and sequenced a 413-bp PCR fragment encompassing the 131-bp 3′ end of the 16S rRNA gene and the 282-bp complete ITS sequence of the reference strain of M. lentiflavum (ATCC 51985). Like other slow growers (11), M. lentiflavum showed a short ITS sequence of 282 bp. This sequence was found to be closely related to the ITS sequences of the mycobacterial cluster comprising M. triplex (92.3% identity), M. genavense (90.8% identity), and M. simiae (90.1% identity). These homology data are in good agreement with those obtained for 16S rRNA (6, 11, 12), which found M. lentiflavum to be closely related to M. simiae, M. triplex, and M. genavense.

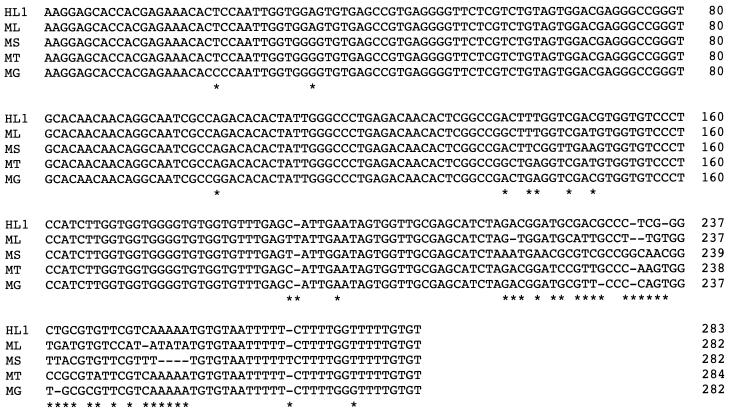

The comparison of the ITS sequence of the HL1 isolate with those of M. lentiflavum (this study), M. triplex (11), M. genavense (11), and M. simiae (8) showed 21 base differences (92.6% identity), 13 differences (95.4% identity), 14 differences (95.1% identity) and 25 differences (91.2% identity), respectively. Figure 1 shows the alignments of the ITS sequences from the HL1 isolate and M. lentiflavum, M. simiae, M. triplex, and M. genavense. The ITS sequence analysis gave an identification different from that provided by 16S rRNA sequencing and incompatible with the phenotypic characteristics of isolate HL1. On the basis of the phenotypic and genotypic data, we identified isolate HL1 as an M. lentiflavum strain.

FIG. 1.

Alignment of complete 16S–23S rRNA ITS sequences from isolate HL1 (HL1), M. lentiflavum ATCC 51985 (ML), M. simiae (MS; GenBank accession no. AB026694), M. triplex (MT; GenBank accession no. Y14189), and M. genavense (MG; GenBank accession no. Y14183). The lengths of the ITS sequences (in nucleotides) are indicated at the end of the sequences. The complete ITS sequence between the end of the 16S rRNA gene and the beginning of the 23S rRNA gene is shown. Dashes indicate aligment gaps, and asterisks indicate variable nucleotide positions.

Discussion.

Disease caused by nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) is common among patients with AIDS. The most common species isolated is the M. avium complex, although the other species including the group of slowly growing NTM such as M. genavense, M. malmoense, M. simiae, and M. triplex have also been described as causes of disseminated disease (3, 5). We report here on the first case of a disseminated infection in an HIV-infected patient caused by M. lentiflavum, a species recently described by Springer et al. (12). Among the 22 isolates reported by Springer et al. (12), most were isolated fortuitously or were traced to contaminated bronchoscopes. Only one isolate was recovered from a patient with spondylodiscitis (12), and another isolate was recovered from a patient with cervical lymphadenitis (7).

The pattern of results obtained by conventional identification procedures, including colony, biochemical, and enzymatic tests, failed to match the patterns of any reported mycobacterial species. The identification of this isolate was accomplished by 16S rRNA sequencing and was confirmed by PCR-PRA of the hsp65 gene. In the present study we also compared the rRNA ITS sequence of this isolate (HL1) with that of the M. lentiflavum reference strain (ATCC 51985). Comparison of the ITS sequences provides guidance on the possible divergence of the ITS sequence within this relatively new species. In summary, we report the first case of disseminated M. lentiflavum infection in an AIDS patient documented by both 16S rRNA gene sequencing and PCR-PRA of the hsp65 gene.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The ITS gene sequences of the M. lentiflavum reference strain (ATCC 51985) and of the HL1 clinical isolate were submitted to GenBank and given accession no. AF317658 and accession no. AF318174, respectively.

REFERENCES

- 1.Devallois A, Seng Goh K, Rastogi N. Rapid identification of mycobacteria to species level by PCR restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of the hsp65 gene and proposition of an algorithm to differentiate 34 mycobacterial species. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2969–2973. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.11.2969-2973.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Böttger E C, Hirschel B, Coyle M B. Mycobacterium genavense sp. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1993;43:841–843. doi: 10.1099/00207713-43-4-841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cingolani C, Sanguinetti M, Antinori A, Larocca L M, Ardito F, Posteraro B, Federico G, Fadda G, Ortona L. Disseminated mycobacteriosis caused by drug-resistant Mycobacterium triplex in a human immunodeficiency virus-infected patient during highly active antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31:177–179. doi: 10.1086/313903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.David H, Lévy-Frébault V, Thorel M F. Methodes de laboratoire pour mycobactériologie clinique. Paris, France: Commission des Laboratoires d'Expertise et de Référence, Institut Pasteur; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Falkinham J. Epidemiology of infection by nontuberculous mycobacteria. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1996;9:177–215. doi: 10.1128/cmr.9.2.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Floyd M, Guthertz L S, Silcox V A, Duffey P S, Jang Y, Desmond E P, Crawford J T, Butler W R. Characterization of an SAV organism and proposal of Mycobacterium triplex sp. nov. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2963–2967. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.12.2963-2967.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haase G, Kentrup H, Skopnic H, Springer B, Böttger E C. Mycobacterium lentiflavum: an etiologic agent of cervical lymphadenitis. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25:1245–1246. doi: 10.1086/516958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kasai H, Ezaki T, Harayama S. Differentiation of phylogenetically related slowly growing mycobacteria by their gyrB sequences. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:301–308. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.1.301-308.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kirschner P, Springer B, Vogel U, Meier A, Wrede A, Kiekenbeck M, Bange F C, Böttger E C. Genotypic identification of mycobacteria by nucleic acid sequence determination: report of a 2-year experience in a clinical laboratory. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:2882–2889. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.11.2882-2889.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rogall T, Wolters J, Flohr T, Böttger E C. Towards a phylogeny and definition of species at the molecular level within the genus Mycobacterium. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1990;40:323–330. doi: 10.1099/00207713-40-4-323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roth A, Fischer M, Hamid M E, Michalke S, Ludwig W, Mauch H. Differentiation of phylogenetically related slowly growing mycobacteria based on 16S–23S rRNA gene internal transcribed spacer sequences. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:139–147. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.1.139-147.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Springer B, Wu W, Bodmer T, Haase G, Pfyffer G E, Kroppenstedt R M, Schröder K H, Emler S, Kilburn J O, Kirschner P, Telenti A, Coyle M B, Böttger E C. Isolation and characterization of a unique group of slowly growing mycobacteria: description of Mycobacterium lentiflavum sp. nov. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:1100–1107. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.5.1100-1107.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]