Abstract

Objectives: This study examined factors contributing to decision conflict and the decision support needs of PrEP-eligible Black patients. Methods:The Ottawa Decision Support Framework (ODSF) was used to guide the development of a key informant guide used for qualitative data collection. Black patients assessed by healthcare providers as meeting the basic criteria for starting PrEP were recruited through the St. Michael's Hospital Academic Family Health Team and clinical and community agencies in Toronto. Participants were interviewed by trained research staff. Qualitative content analysis was guided by the ODSF, and analysis was done using the Nvivo. Results: Four women and twenty-five men (both heterosexual and men who have sex with men) were interviewed. Participants reported having difficulty in decision making regarding adoption of PrEP. The main reasons for decision-conflict regading PrEP adoption were: lack of adequate information about PrEP, concerns about the side effects of PrEP, inability to ascertain the benefits or risk of taking PrEP, provider's lack of adequate time for interaction during clinical consultation, and perceived pressure from healthcare provider. Participants identified detailed information about PrEP, and being able to clarify how their personal values align with the benefits and drawbacks of PrEP as their decision support needs. Conclusion:Many PrEP-eligible Black patients who are prescribed PrEP have decision conflict which often causes delay in decision making and sometimes rejection of PrEP. Healthcare providers should offer decision support to Black patients who are being asked to consider PrEP for HIV prevention.

Keywords: Decision support, HIV Pre-exposure prophylaxis, Black patients, Decision support needs, Decision conflict

Introduction

There are noted racial disparities in the incidence of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) for African, Caribbean, and Canadian Black (Black) populations in Ontario, Canada. Although Black people represent only 4.7% of the Ontarian population, they account for 30% of HIV prevalence and 25% of new infections in the province. 1 There are also high rates of HIV in Black individuals with a history of STI diagnosis.2, 3 HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is recommended for populations at high ongoing risk for infection. 4 However, research evidence shows that acceptance of PrEP in Toronto is particularly low among young Black men and Black men who have sex with women. 5 There is a growing need to find the best strategies for supporting PrEP scale-up among Black populations in Ontario.

Some studies have examined factors affecting uptake of PrEP in Toronto, especially those related to lack of PrEP awareness, access to care, stigma, providers attitude, cost and structural barriers 6–9. Other studies have also focused on improving adherence to PrEP10–14. Improving the quality of medication use for either prevention or treatment purposes requires that ‘adoption’ take place before ‘adherence’. While adherence refers to compliance with a medication administration schedule, ‘adoption’ can be described as an internally endorsed commitment to integrating the medication into one's personalized risk reduction plan 15 . ‘Adoption’, therefore, requires a quality decision-making process.

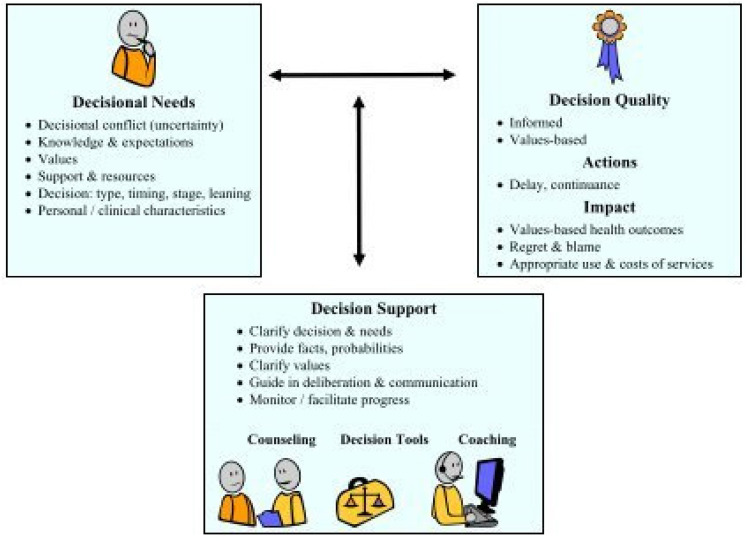

There has been a growing interest in improving the quality of the decision-making process in health. The Ottawa Decision Support Framework (ODSF) is an evidence-based, transdisciplinary framework used to develop decision support interventions by identifying factors that contribute to decisional conflicts, or the uncertainty about which course of action to take when there is a choice among competing options16–19. According to the ODSF, decisional conflict can potentially emerge from two sources: the inherent difficulty associated with having to choose among competing options, and the modifiable determinants of decisions (needs) that make decision making difficult.20, 21 The foundation of interventions for decision support is the implementation of interventions that address those needs.

The Ottawa Decision Support Framework asserts that a patient's decisional needs will affect decision quality, which in turn affects actions or behaviours, health outcomes, emotions, and appropriate use of health services.22, 23 In addition, research on self-determination theory (SDT) indicates that informed and autonomous decision-making is a central component to facilitating motivation for long term maintenance of health behaviors, such as daily oral PrEP. This concept has been demonstrated in clinical trials across various populations and health domains,24–28 but has only recently received attention in HIV prevention.29, 30

Despite the decision to adopt PrEP being complex, there are limited studies that have investigated the decisional needs of Black patients who are asked to consider adopting PrEP for HIV prevention 31 . The main objective of this study was to assess the decisional support needs of Black patients who are offered PrEP for HIV prevention. Specifically, our goal was to: (1) determine the factors contributing to difficulty in decision making regarding the adoption of PrEP for HIV prevention, and (2) determine the support and resources required by Black patients to make a quality decision regarding the adoption of PrEP for HIV prevention.

Conceptual framework

We used the Ottawa Decision Support Framework (ODSF) and the Self Determination Theory (SDT) as the framework for this study.

The ODSF conceptualizes the support needed by patients, families, and their practitioners for difficult’ decisions with multiple options whose features are valued differently. It guides practitioners and researchers in assessing participants’ decisional needs, providing decision support interventions (clinical counseling, decision tools, decision coaching), and evaluating their effects on decisional outcomes. As shown in figure 1, the ODSF has three key elements: a) decisional needs, b) decision outcomes, and c) decision support. Decisional needs are deficit that can adversely affect the quality of a decision (informed, match most valued features) and require tailored decision support. Decision Support is structured assistance in deliberating about the decision and communicating with others. It is tailored to the patients’ decisional needs and aims to achieve decisions that are informed and based on features that patients value most. Decision outcome is the extent to which the chosen option is: a) informed (patient has essential knowledge and realistic outcome expectations) and b) values-based (choice matches features that matter most to the patient) 16–19. Decisional needs include;

- Decisional conflict: a state of personal uncertainty about which course of action to take when choice among options involve risk, loss, regret, or challenge to one's personal values.

- Inadequate knowledge: Unaware or lack of cognizance of essential relevant facts to make a decision: health problem/condition; options; features of options (known benefits, harms, and other outcomes and features; scientifically uncertain outcomes)

- Unrealistic expectations: Unaware of one's chances or probabilities of outcomes (e.g., benefits, harms, other) for each option; or perceptions of one's chances of outcomes are not aligned with the current evidence for similar patients

- Unclear values or personal importance: Lack of clarity regarding desirability or personal importance of the features of options: known benefits, harms, other outcomes and features (e.g., for PrEP – reduced anxiety about HIV transmission versus the burden of daily medication; scientifically uncertain outcomes (e.g., for PrEP – HIV prevention versus side effect of medication).

- Inadequate support: Lack of quality, appropriate amount, and/or timely access to support and resources needed to make and implement the decision. Examples include; a) Information inadequacy / overload, b) Inadequate perceptions: others’ views/practices: Unaware of, misperceives, or lacks clarity about what others decide or what important others think is the appropriate choice (e.g., spouse, family, friends, health professional(s), society), c) Social pressure: Perception of persuasion, influence, coercion from important others (e.g., spouse, family, friends, health professionals, or society) to choose a specific option.

- Complex decision characteristics such as time, timing, or stage and leaning to a specific option

- Special needs arising from patients’ personal or clinical characteristics

Figure 1.

Ottawa Decision Support Framework (ODSF). 19

We adopted the decisional needs elements of the ODSF for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis to understand the decisional needs of Black patients who are being asked to consider PrEP for HIV prevention.

The Self Determination Theory (SDT) is a social psychological theory of motivation that contends that humans have natural inclinations towards health protective activities. These natural inclinations are optimized through the support of human's basic psychological needs for autonomy (volition and freedom), competence (perceived ability to attain a desired goal), and relatedness (connection to and caring from others). SDT also articulates how sociocultural factors can either facilitate or undermine volition 24–28. The healthcare climate questionnaire was developed based on the SDT. We utilized the healthcare climate questionnaire to collect data on participants’ experience with their provider to explore the influence of ‘relatedness’ on PrEP decision making.

Methods

Study measures

Different interview guides were used depending on participant's interest in taking PrEP at the time of the interview; the three guides were for a) those interested in taking PrEP, b) those who were uninterested in taking PrEP and c) those who were still undecided. Questions were largely the same across the three guides, but wording differed based on participants’ interest in taking PrEP. We used open-ended questions and specific probes to elicit responses related to characteristics of decisional needs of Black patients being asked to adopt PrEP. The questions on decisional needs were based on recommendations for decisional needs assessment in populations 19 . We asked questions relating to decision stage, knowledge, values clarifications, certainty, support, timing, and healthcare climate experience. We also collected participants demographic and clinical data. For example, we asked the following questions to explore participants’ knowledge; (a)Could you tell me what you already know about PrEP? (b)What things about PrEP are still not clear to you? What else about PrEP would you like to know? (c)What type of information would help clarify these things? (d) Do you know where you could find some of these answers? Where? (e) What sources would you trust to give you the information to help clarify? Why? (f) What sources wouldn't you trust? Why not? We used the following questions to explore the presence of decision conflict; (a) Tell us about any point where you were unsure about whether to take PrEP? (b) What were some of the things you were unsure about?

Questions on healthcare climate experiences were also included to understand how the Self Determination Theory constructs (autonomy, competence and relatedness) influence Black patients’ decision-making experiences regarding PrEP adoption for HIV prevention. For example; Tell me about your experience talking with your healthcare provider about PrEP; What did you like about the health provider? What did you not like about the experience? Do you feel like you have a say in what happened to you there? Why? Why not? Did you feel like your voice was heard or what you had to say mattered? How would you have liked those experiences to be different?

Study design, patient recruitment and data collection

The full details of the study design, recruitment and data collection have been previously described elsewhere. 32 A venue-based non-probability sampling process was used to recruit participants through the St. Michaels Hospital Academic Family Health Team, and community agencies. Healthcare providers in participating sites identified participants who met basic eligibility criteria for starting HIV PrEP. Participants were deemed eligible for the study if they were at least 18 years old, identified as African, Caribbean, and/or Canadian Black, living in the greater Toronto metropolitan area, and could speak and understand English. Trained research staff explained the purpose of the study and also obtained written informed consent from all participants referred to the study before enrolment in the study. The interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Participants also completed a short interviewer administered survey to identify patient demographics and clinical characteristics.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were generated for the demographic and clinical characteristics. Qualitative content analysis of each transcript was guided by the ODSF. The unit of analysis was an individual key informant interview. Qualitative responses related to the various section of the ODSF and healthcare climate experiences were coded using the major themes from the interview guide and themes that emerged from participants’ responses. Six transcripts were initially coded by two research staff members to develop the draft codebook. These transcripts were later recoded. Two additional team members, including the Principal Investigator, reviewed and provided input on the draft codebook prior to finalizing it. Additional themes that emerged during the coding process were incorporated. Interview transcripts were coded into the themes by two research staff members using NVivo software. Inter-rater reliability (IRR) was assessed whereby six interview transcripts were double-coded by the 2 research staff members. A high level of agreement was achieved for all the identified themes (Kappa scores of 0.83,0.86 and 0.89 for 3 rounds of IRR)

Ethical approval and informed consent

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Board of St. Michael's Hospital, Unity Health Toronto. The approval number is 18-022. All patients were provided written informed consent prior to enrolment.

Author contributions

The contributions of each author are as follows: [details omitted for double-anonymized peer review].

Results

Demographics and clinical characteristics

A total of 29 individuals agreed to participate in the study. The decision stage (interest in taking PrEP), sexual orientation, and gender of participants are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Interest in Taking PrEP

| Interest in taking PrEP | Men | Women | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSM a | Heterosexual | Bisexual | |||

| Decided Yes | 7 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 12 |

| Decided No | 1 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 7 |

| Undecided | 6 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 10 |

| Total | 14 | 11 | 2 | 2 | 29 |

MSM: Men who have sex with men

As described in Table 2, the majority (76%) of patients were between the 25-45 years age range. In addition, most (97%) had at least a secondary school diploma. Only one third (31%) of participants reported being in a monogamous relationship with a recently tested HIV negative partner. In addition, some (10%) reported an ongoing sexual relationship with a partner who is HIV- positive. Thirty-eight percent of participants reported unprotected anal sex with a man in the last 6 months. Although most (97%) participants said they had been tested for HIV, only 77% of these participants did so in the last 6 months. The majority (93%) said they were HIV negative, while a few (7%) reported not being aware of the result of their HIV test. Almost all the participants (93%) had not been diagnosed with a sexually transmitted infection in the last 6 months.

Table 2.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

| Demographic and Clinical Characteristics | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| < 24 | 4 (14%) |

| 25-35 | 14 (48%) |

| 36-45 | 8 (28%) |

| >46 | 3 (10%) |

| Highest level of education: | |

| High School diploma or GED equivalent | 8 (30%) |

| College/Bachelor's degree | 14 (47%) |

| Graduate degree | 6 (20%) |

| Professional degree (e.g., Medicine, Law) | 1 (3%) |

| Sexual Attraction*: | |

| Men only | 8 (28%) |

| Women only | 10 (34%) |

| Both men and women | 11 (38%) |

| Trans men | 3 (10%) |

| Trans women | 2 (7%) |

| Non-binary | 3 (10) |

| Married (Within or outside Canada): | |

| Yes | 11 (38%) |

| No | 18 (62%) |

| Monogamous sexual relationship (with recently tested HIV negative partner): | |

| Yes | 9 (31%) |

| No | 20 (69%) |

| Unprotected recent anal sex in the last 6 months: | |

| Yes | 11 (38%) |

| No | 18 (62%) |

| Ongoing sexual relationship with HIV+ partner: | |

| Yes | 3 (10%) |

| No | 25 (86%) |

| Don't Know | 1 (3%) |

| Diagnosis of Gonorrhea, Chlamydia, Syphilis in the past 6 months: | |

| Yes | 2 (7%) |

| No | 27 (93%) |

| Been tested for HIV | |

| Yes | 28 (97%) |

| No | 1 (3%) |

| After HIV testing, participants were: | |

| HIV negative | 26 (93%) |

| HIV positive | 0 (0%) |

| Don't know | 2 (7%) |

Options for HIV Prevention

When asked about the options available to them for HIV prevention besides PrEP, participants identified abstinence, condoms, monogamy, Post-exposure Prophylaxis (PEP) and regular HIV testing. See Table 3. In terms of their preference for the various HIV prevention options identified, most (86%) participants identified use of condoms as an HIV prevention option, while fewer (20%) said regular HIV testing is an option they would consider besides PrEP.

Table 3.

Options for HIV Prevention

| Options for HIV Prevention | # of Patients (n=29) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Abstinence | 16 | 57% |

| 2. Use of condoms | 25 | 86% |

| 3. Monogamy | 7 | 24% |

| 4. Post-Exposure Prophylaxis (PEP) | 8 | 28% |

| 5. Regular HIV testing for self and partner | 6 | 20% |

Characteristics of Decisional Conflicts

Majority of study participants (many of the ‘undecided about PrEP / decided not to take PrEP’ participants, and few ‘decided to take PrEP’ participants) expressed views indicative of the presence of decisional conflicts. As shown in Table 4, characteristics of decisional conflict included; concerns about the side effects of PrEP; uncertainty about the decision to start PrEP; wavering between choosing PrEP or other HIV prevention options; delay in starting PrEP; and questioning personal values.

Table 4.

Characteristics of decisional conflicts expressed by patients

| Characteristics of decisional conflicts | Sample Quotes |

|---|---|

| • Thought of uncertainty or being unsure about decision • Concerns about undesired side effect • Wavering between choices • Delay in decision making • Questions about personal values | ‘‘Yes, I was unsure, it's something you are putting in your body, so I had a lot of questions about it ‘‘(participant #017 –Undecided about PrEP) ‘‘ I kept thinking over and over again about the issue of damage that could happen to my body organ if I take it’’(participant #005 –Decided ‘No’ to PrEP) ‘‘So, at that point I was kind of wavering if I should even take it’’ (participant #008 –Undecided about PrEP) ‘‘And if my mind was clear, then, once I got the pills, I would have taken it immediately. But, I kept thinking…. is it going to be effective? So, that thought affected my decision’’ (participant #012- Undecided about PrEP) ‘‘But I think my initial apprehension of going on PrEP was just more psychological in the sense that it might lead to promiscuity. But I think it was just the apprehension of not being as vigilant as I would have wanted to. So, that was my initial apprehension about going on PrEP’’ (participant 029 – Decided ‘Yes’ to PrEP) |

Factors contributing to difficulty in decision making regarding PrEP

When asked about the factors contributing to difficulty in decision making regarding PrEP, participants identified several factors categorized under the 3 domains of the ODSF, namely: inadequate knowledge and unrealistic expectations, lack of clarity about personal values, and issues of support and resources. We presented sample quotes under each of these major themes and subthemes in Table 5.

Table 5.

Factors affecting / contributing to difficulty in decision making regarding PrEP

| Factors affecting decision making about PrEP | Examples from participants |

|---|---|

|

1. Support and Resources Unclear about the support of partner Social pressure Unclear or biased views from others Lack of resource/support from the healthcare provider: Time - Detailed information about PrEP- Pressure from healthcare provider |

‘‘ I have a partner back home and I have to discuss with her, so that's the most difficult thing. Even after meeting the doctor, I will still have to call and talk to her (my partner) about this’’ (participant #019 –undecided about PrEP) ‘‘I am thinking about my partner and my mom. How is it going to affect my family, and what's best for them? I feel like I should just be able to make a decision for myself’’ (participant #019-undecided about PrEP) ‘‘When you go to the clinic and you want to talk about PrEP, and they ask you, ‘What is the reason why you want to take PrEP? And I’m like, ‘playing around’. Then the response is…. ‘really?’. The next question that might come is: Are you married? And if you say yes, there is this look like judgemental look and they say: ‘you are not being faithful. Judgemental reason is so alarming especially when it comes to people of color’’ (participant # 025-undecided about PrEP) ‘‘ I just asked some basic information and I knew I would have to do the heavy lifting for the most part. Because again in the split of time that you have with your healthcare professional it's usually very limited, right, so you usually can't do a lot of in-depth, comprehensive type conversation’’ (participant #006- undecided about PrEP) ‘‘My conversation with my healthcare provider didn't really help me as much because again, he did not really have much information about it. Yes, the little information didn't really sway me that much and so I’m still undecided’’ (participant #022 – undecided about PrEP) “She was trying to convince me that even if I am faithful, I could still practice the use of PrEP and I’m like: ‘why would I continue to take medication every day, subjecting my kidney to awful amount of stress?’. I’d rather remain in this way than taking medication every day” (participant #007 – decided ‘No’ to PrEP) |

|

Factors contributing to difficulties in decision making regarding PrEP | |

| Factors affecting decision making about PrEP | Sample Quotes |

|

2. Inadequate knowledge and expectations Lack of information Unrealistic expectations of benefits and harms |

‘‘Yes, for me, it was just more information on things like access: I wasn't sure if my health plan could cover it or if I could afford it’’ (participant #002 –undecided about PrEP) ‘‘Because I don't know. I haven't known it for a long time, so I can't trust it within these few months or days or weeks. I need to have information about it to assure me that when I start this medication it will not harm me or affect me’’ (participants #018-decided ‘No’ to PrEP) ‘‘I think PrEP doesn't work’’ (participants #009- decided ‘No’ to PrEP) ‘‘The thought of the risk of getting addicted to the drug’’ (participants #024-decided ‘No’ to PrEP) |

|

3. Lack of clarity on personal values Concerns about the side effects of PrEP Concerns about the benefits of PrEP compared to condom use Inability to ascertain the benefits versus risk |

‘‘I actually want to use it, but like I already told you over, and over again, that the issue of damages that could happen to my body organs as a result of prolong use of it, is my major concern’’ (participant #010 undecided about PrEP) ‘‘I was unsure about the effectiveness. For condom I know it's not 100% protective, but there is conflicting information about the effectiveness of PrEP’’ (participant #016 – undecided about PrEP) ‘‘I need to weigh the pros and cons, which one outweighs the other; and for now, its hard for me to say’’ (participant #027- decided ‘No” to PrEP) |

Inadequate knowledge and unrealistic expectations

Participants mentioned that information gaps contributed to decisional conflict including the following themes: lack of information on the cost of PrEP, affordability and access, lack of information on the side effects of PrEP (especially the effect on major organs of the body), and lack of information on the efficacy of PrEP (and how it compares to use of condom in reducing risk of HIV infection).

Lack of clarity on personal values

Participants’ inability to clarify how the benefits and harms of PrEP affects their personal values was also cited as one of the factors affecting decision making. Some participants were unsure about the pros and cons of PrEP, while some felt knowing more about the side effects of the drug and how it will impact their body organs would enable them to weigh this risk against the benefits of PrEP.

Support and Resources

Participants identified unclear or biased views from a partner, family member or society; lack of resources or support from healthcare providers, pressure from healthcare providers, and the difficulty associated with making this type of decision as contributing to the difficulty in decision making.

Knowledge/Information required for decision making regarding PrEP)

Many of the participants, including those who expressed interest in taking PrEP said the following information would help clarify uncertainty regarding PrEP, and thereby can facilitate quality decision making:

How to access PrEP

Participants identified information on how to access PrEP with specific details about ‘where and how’, as crucial to their decision making on PrEP. Participants also said the cost of PrEP, and whether the various public and private health insurance will cover it is important information to have. Some participants expressed interest in knowing how people without health insurance can access PrEP, especially those with precarious work or immigration status.

Dosage administration and precautions

Participants said a general pharmaceutical knowledge about PrEP would be helpful in decision making. For instance, some participants said they would like to know what time of day that is best to take PrEP, any food requirements or food-drug interaction, and if PrEP can be administered alongside any other drugs.

How long PrEP has been available

Information about when PrEP was developed, how long it has been in use, and when it was introduced to the market were identified by participants as relevant for decision making.

Medication efficacy and adherence requirements

Participants were interested in knowing the extent to which PrEP protects against HIV, and if it protects against sexually transmitted infections. Information on how adherence affects effectiveness of the medication, and the minimum number of days patients need to take it before having sex were identified as helpful for decision making.

How PrEP prevents HIV infection

Participants said a non-scientific explanation of how PrEP works to prevent HIV would be helpful to facilitate quality decision making.

Medication monitoring and follow-up requirements

Participants were interested in knowing what evaluations would be performed before starting PrEP, including lab work or physical examinations. Additionally, participants were interested in knowing how adherence to the medication would be monitored, how often the medication would be refilled, and where the medication can be refilled.

Side Effects

Participants would like to know the long-term side effects of PrEP, especially damage to the organs of the body, and the effect PrEP has on mood (such as whether it would contribute to depression). Participants also indicated that clarity on the safety of the medication would help in decision making.

Value clarifications to enhance decision making

Table 6 describes the benefits and drawbacks of PrEP identified by participants which has to be clarified with reference to their personal values to facilitate decision making regarding PrEP.

Table 6.

Benefits and Drawbacks of Adopting PrEP

| Benefits of PrEP | Drawbacks of PrEP |

|---|---|

| HIV prevention | Cost of the medication |

| Reduced anxiety about HIV transmission | The burden of daily medication |

| Self care or love | Decreased condom use or increased number of sexual partners |

| Sex without using condoms | Side effects |

| Stigma with taking medication for preventive purposes |

Supports and resources for decision making

Preferred sources of trusted information

Participants described what they felt would be reliable sources of information about PrEP. Preferred sources included hospital-based websites, research-based organization websites, and government agency websites (like Health Canada, the Center for Disease Control and the Canadian AIDS Treatment Information Exchange). Some participants also mentioned their healthcare providers were trusted sources from whom they would seek information, while others said they sought out information from Black-serving community organizations.

Preferred means of provision of decision support

Participants listed several preferred ways through which decision support could be provided. These included: pamphlets that explain all the information relevant to taking PrEP, brochures, websites, social media pages, as well as the use of videos, or infographics to explain necessary information.

Discussion and Conclusion

Discussion

This study reveals that PrEP eligible Black patients have difficulties in decision making when asked to consider PrEP for HIV prevention. Also, this study describes the factors that make this decision difficult as well as the decision support needs of Black patients who are being asked to adopt PrEP for HIV prevention.

Access to PrEP, especially the knowledge of health insurance coverage was identified as one of the factors affecting decision-making about PrEP. This is consistent with findings from other studies which identified lack of access as a barrier to uptake and adherence to PrEP especially among venerable populations 6–11. Government policies must evolve to improve access to PrEP especially for Black communities to achieve the goal ending the HIV epidemic.

In addition, health care providers’ lack of PrEP knowledge and inadequate consultation time was also identified as factors contributing to difficulties in decision making. This result aligns with another study on provider-patient communication on PrEP, which identified providers’ lack of PrEP knowledge and time constraints during clinical appointments as the major barriers to engaging patients in PrEP-related discussion. 33 Traditionally, only a few prescribers have enough time to discuss this broad range of information with their patients during consultations. 34 A decision support aid that provides targeted medical information based on a patient or population's specific needs may help bridge this gap.

Interestingly, patients in this study reported they felt pressured by healthcare providers, and that this pressure contributed to difficulties in decision making. This finding seems to highlight results from other studies that have reported the influence of patient's race or gender identity on healthcare providers’ clinical decision on PrEP prescribing 34–36. Pressuring patient is concerning, as healthcare providers are meant to guide patients into making an informed decision rather than pressure patients into taking PrEP without thought and consideration. The ODSF defines an informed decision as one in which the patient knows the various options available and their possible options; clarifies their expectations so that they are reasonable and possible; and is conscious of the need to consider the pros and cons16–19

There appears to be similarities between the factors affecting decision making and the decision support needs expressed by patients. This may suggest that those items identified both as sources of difficulty in decision making, and as decision support needs are not only significant but need to be given adequate attention in the design of decision support aids for PrEP eligible Black patients. To be helpful, decision support aids must address all the knowledge gaps that have been identified by patients as necessary for making informed decisions. 37

A surprising decision support need identified by patients was knowing ‘how long PrEP has been in use’. There are two probable explanations for this information need. One probable explanation for this may relate to issue of distrust in medical science in Black communities 37 . This is not unfounded as the community has genuine reasons to doubt the sincerity of the medical community. It is unclear if providing this information on PrEP will be sufficient to address this seeming mistrust, but it will probably help patients decide to take PrEP if they know that PrEP has been around for a while, and is not just a new medical innovation that is being tested on Black patients. Another explanation is that the longer a medication has been available, the stronger the evidence of the safety and efficacy of the medication, and the higher the probability of patients having trust in the medication. These explanations support the importance of providing information on ‘how long PrEP has been in use’ to enhance quality decision making.

To address the decision support needs of Black patients adopting PrEP for HIV prevention, a decision support tool must incorporate the information required for quality decision making, provide a way to clarify the importance of the benefits and harms of PrEP to their personal values, and also help the patient identify supports and resources available to them for quality decision making. The decision support intervention must also address the issue of autonomy, which apparently is a source of problem in decision making for Black patients.

Limitations

Although we recruited individuals from key populations who are at risk of HIV in the Black community, we were unable to recruit equal number of women compared to men. Decisional needs of Black women regarding PrEP are very important, therefore we envisage that future research will consider this important aspect of the study.

The contrasts between MSM and heterosexual men; the issue of PrEP stigma and perceived discrimination especially relating to Anti-Black racism was not explored in this study. Future study should explore how these issues affect the decisional needs for adoption of PrEP for HIV prevention.

Conclusion

PrEP-eligible Black patients who are being asked to adopt PrEP for HIV prevention experience difficulties in decision making due to a lack of information about PrEP, concerns about the side effects of PrEP, inability to ascertain the benefits and risk of PrEP, lack of support from healthcare providers, and time constraints during interactions with healthcare providers. Provision of information on how PrEP works, the side effects, dosage administration and precautions, how long PrEP has been available, and how to access PrEP will improve the decision-making process for PrEP-eligible Black patients who are prescribed PrEP for HIV prevention. A decision support aid that incorporates PrEP-related information, and which provides a way for patients to clarify their personal values on the benefits and drawback of PrEP will improve the PrEP decision-making process for Black patients.

Practice Implications

Healthcare providers should offer decision support to Black patients who are being asked to consider PrEP for HIV prevention. This decision support should aim at increasing understanding of PrEP, the associated benefits and risks. It should also enable Black patients at risk of HIV to assess how these benefits and risks align with their personal values. The decision support should also be offered in an autonomy supportive environment, devoid of racial and gender bias.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: LaRon Nelson (LN), the principal investigator of this study is a shareholder of tuliptree systems, LLC—the company that owns the decision support aid that is used in this trial. As such, LN has a direct financial interest in the success of the decision support aid and its continued use as an intervention. LN has accepted a conflict of interest (COI) management agreement with Unity Health Toronto St. Michael's Hospital to minimize any potential undue influence on the study's outcomes. The COI management plan stipulates that LN will neither be involved in the recruitment of participants nor in obtaining informed consent.

Ethical Statement: This study was approved by the St. Michael's hospital Research Ethics Board (approval number 18-022).

All study participants were provided written informed consent prior to enrolment.

Funding: This project was funded by the Ontario HIV Treatment Network (OHTN) Chair Award in Implementation Science in Black communities in Ontario, Canada.

ORCID iDs: Wale Ajiboye https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9526-2895

LaRon Nelson https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2630-602X

Pascal Djiadeu https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9708-6530

De Anne Turner https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6987-6065

M’Rabiu Abubakari https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1718-0381

Cheryl Pedersen https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4454-9412

Zhao Ni https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9185-9894

Genevieve Guillaume https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2927-4470

References

- 1.Ontario HIV. Treatment Network. African, Caribbean and Black Communities. The Ontario HIV Treatment Network. Accessed February 21, 2020. https://www.ohtn.on.ca/research-portals/priority-populations/african-caribbean-and-black-communities/

- 2.Haddad N, Li J, Totten S, McGuire M. HIV in Canada—Surveillance Report, 2017. Canada Commun Dis Rep. 2018;44(12):324–332. doi: 10.14745/ccdr.v44i12a03 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2012.; 2012. doi: 10.1136/bmj.282.6264.652-a [DOI]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: US Public Health Service. Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis for the Prevention of HIV Infection in the United States-2017: A Clinical Practice Guideline.; 2018. Accessed December 1, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/tg-2015-

- 5.Zhabokritsky A, Nelson LRE, Tharao W, et al. Barriers to HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis among African, Caribbean and Black men in Toronto, Canada. PLoS One. 2019;14(3). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0213740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Newman PA, Guta A, Lacombe-Duncan A, Tepjan S. Clinical exigencies, psychosocial realities: negotiating HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis beyond the cascade among gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men in Canada. J Int AIDS Soc. 2018;21(11):e25211. doi: 10.1002/jia2.25211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lacombe-Duncan A, et al. Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) Implementation for Gay, Bisexual, and Other Men Who Have Sex with Men: Implications for Social Work Practice. Health Soc Work. 2021;46(1):22–32. doi: 10.1093/hsw/hlaa038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chandler R, Hull S, Ross H, et al. The pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) consciousness of black college women and the perceived hesitancy of public health institutions to curtail HIV in black women. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:1172. 10.1186/s12889-020-09248-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taggart T, Liang Y, Pina P, Albritton T. Awareness of and willingness to use PrEP among Black and Latinx adolescents residing in higher prevalence areas in the United States. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(7):e0234821. 10.1371/journal.pone.0234821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brooks RA, Landovitz RJ, Kaplan RL, Lieber E, Lee SJ, Barkley TW. Sexual risk behaviors and acceptability of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis among HIV-negative gay and bisexual men in serodiscordant relationships: A mixed methods study. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2012;26(2):87–94. doi: 10.1089/apc.2011.0283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brooks RA, Kaplan RL, Lieber E, Landovitz RJ, Lee SJ, Leibowitz AA. Motivators, concerns, and barriers to adoption of preexposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention among gay and bisexual men in HIV-serodiscordant male relationships. AIDS Care - Psychol Socio-Medical Asp AIDS/HIV. 2011;23(9):1136–1145. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2011.554528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Légaré F, Kearing S, Clay K, et al. Are you SURE? Assessing patient decisional conflict with a 4–item screening test. Can Fam Physician. 2010;56(8):308–322. Accessed June 2, 2021. /pmc/articles/PMC2920798/. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mustanski B. Ethical and regulatory issues with conducting sexuality research with LGBT adolescents: A call to action for a scientifically informed approach. Arch Sex Behav. 2011;40(4):673–686. doi: 10.1007/s10508-011-9745-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ottawa Hospital Research Institute. User Manual for Decision Making Scale.; 1995. Accessed December 1, 2020. www.ohri.ca/decisionaid.

- 15.World Health Organization. Adherence to Long Term Therapies: Evidence for Action.; 2003.

- 16.3rd International Shared Decision Making Conference. Implementing Shared Decision Making In Diverse Health Care Systems And Cultures.; 1999.

- 17.Ottawa Hospital Research Institute. User Manual: Decisional Conflict Scale. Ottawa Hospital Research Institute. Published 1993. Accessed December 5, 2020. https://decisionaid.ohri.ca/eval_dcs.html

- 18.O’Connor A, Jacobsen M. Workbook on Developing and Evaluating Patient Decision Aids. Ottawa Hosp Res Inst. Published online 2003. www.ohri.ca/decisionaid. Accessed December 5, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jacobsen MJ, O’Connor A, Stacey D. Decisional Needs Assessment in Populations: A workbook for assessing patients’ and practitioners’ decision making needs. Ottawa Hosp Res Inst. Published online 1999. www.ohri.ca/decisionaid [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ng CJ, Mathers N, Bradley A, Colwell B. A “combined framework” approach to developing a patient decision aid: The PANDAs model. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12913-014-0503-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.International Patient Decision Aid Standards Collaboration. IPDAS Voting Document-2nd Round.; 2005.

- 22.Ottawa Hospital Research Institute. Ottawa Decision Support Framework to Address Decisional Conflicts. Ottawa Hospital Research Institute. Published 2006. http://www.ohri.ca/decisionaid/

- 23.Stacey D, Légaré F, Boland L, et al. 20th Anniversary Ottawa Decision Support Framework: Part 3 Overview of Systematic Reviews and Updated Framework. Med Decis Mak. 2020;40(3):379–398. doi: 10.1177/0272989X20911870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Williams GC, Patrick H, Niemiec CP, et al. Reducing the health risks of diabetes: How self-determination theory may help improve medication adherence and quality of life. Diabetes Educ. 2009;35(3):484–492. doi: 10.1177/0145721709333856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Williams GC, Grow VM, Freedman ZR, Ryan RM, Deci EL. Motivational Predictors of Weight Loss and Weight-Loss Maintenance. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1996;70(1):115–126. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.70.1.115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Williams GC, Cox EM, Kouides R, Deci EL. Presenting the facts about smoking to adolescents: Effects of an autonomy-supportive style. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153(9):959–964. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.9.959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ryan RM, Deci EL, Williams GC. Facilitating health behaviour change and its maintenance: Interventions based on Self-Determintation Theory. Eur Heal Psychol. 2008;10:2–5. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ng JYY, Ntoumanis N, Thøgersen-Ntoumani C, et al. Self-Determination Theory Applied to Health Contexts: A Meta-Analysis. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2012;7(4):325–340. doi: 10.1177/1745691612447309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nelson LRE, Wilton L, Agyarko-Poku T, et al. Predictors of condom use among peer social networks of men who have sex with men in Ghana, West Africa. PLoS One. 2015;10(1). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0115504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wheeler DP, Fields SD, Beauchamp G, et al. Pre-exposure prophylaxis initiation and adherence among Black men who have sex with men (MSM) in three US cities: results from the HPTN 073 study. J Int AIDS Soc. 2019;22(2). doi: 10.1002/jia2.25223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McNulty MC, Ellen Acree M, Jared Kerman H, “Herukhuti” Sharif W, Schneider JA. Shared decision making for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) with black transgender women. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2021. DOI: 10.1080/13691058.2021.1909142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nelson LE, Ajiboye W, Djiadeu P, et al. A web-based intervention to reduce decision conflict regarding hiv pre-exposure prophylaxis: Protocol for a clinical trial. JMIR Res Protoc. 2020;9(6). doi: 10.2196/15080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wilson K, Bleasdale J, Przybyla SM. Provider-Patient Communication on Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (Prep) for HIV Prevention: An Exploration of Healthcare Provider Challenges. Health Commun. Published online. 2020:1–10. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2020.1787927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Williams CC, Newman PA, Sakamoto I, Massaquoi NA. HIV prevention risks for Black women in Canada. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68(1):12–20. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.09.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Calabrese SK, Earnshaw VA, Underhill K, Hansen NB, Dovidio JF. The impact of patient race on clinical decisions related to prescribing HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP): assumptions about sexual risk compensation and implications for access. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(2):226–240. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0675-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lelutiu-Weinberger C, Golub SA. Enhancing PrEP Access for Black and Latino Men Who Have Sex With Men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;73(5):547–555. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.International Patient Decision Aid Standards Collaboration. IPDAS 2005: Criteria for Judging the Quality of Patient Decision Aids. Published online 2005:1–3. www.ipdas.ohri.ca