Abstract

Introduction

Despite proven benefits, physical activity participation remains low in patients with coronary heart disease (CHD). Scientific evidence suggests that mobile health (mHealth)-based gamification interventions could increase physical activity levels. However, several systematic reviews demonstrated that most gamification intervention designs do not appropriately leverage theories from health behaviour models, and empirical evidence on the efficacy of such interventions among patients with CHD is still emerging. This study embeds the principles of behavioural economics into a gamification intervention based on a smartphone app (WeChat applet) to explore whether a mHealth-based gamification intervention can improve participation in physical activity and other related physical and psychological outcomes in patients with CHD.

Methods

We propose a single-blinded three-arm randomised controlled trial with 108 patients with CHD, who will be randomly divided into three groups (Control group: WeChat applet+step goal setting; Individual group: WeChat applet+step goal setting+gamification; Team group: WeChat applet+step goal setting+gamification+collaboration). The interventions will last for 12 weeks and follow-up for 12 weeks. All patients will receive only WeChat applet-based step goal setting in the follow-up period. The primary outcome is physical activity participation, which includes a change in daily steps and self-reported physical activity from the baseline to 12 and 24 weeks, and the proportion of patient-days that step goals achieved in 12 and 24 weeks. The secondary outcomes include biomedical and lifestyle-related risk factors, intrinsic motivation, enjoyment, competence, autonomy and relatedness, social support and mental health and patients’ satisfaction, perceptions and intervention experience.

Ethics and dissemination

The Human Research Ethics Committee of the School of Nursing, Jilin University (HREC 2020122401) approved this. The results will be published in peer-reviewed journals and presented at conferences.

Trial registration number

ChiCTR2100044879; Pre-results.

Keywords: physical activity, behavioral intervention, mobile health, gamification, randomized controlled trial

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Our WeChat applet-based gamification intervention is technology based and could improve physical activity adherence in patients with coronary heart disease.

This study is based on a theoretical framework and will provide insights into how to use mobile health and game elements to promote patients’ intrinsic motivation, thereby increase adherence.

This study will examine patients’ psychological needs, intrinsic motivations, perceptions, and experience, which will allow us to understand the internal psychological mechanisms of gamification intervention to promote physical activity.

The study is limited to patients with smartphones and a WeChat account, which could lead to a selective bias.

The gamification interventions are comprehensive and it would be challenging to analyse the component that worked.

Background

Coronary heart disease (CHD) is the leading cause of mortality in China. Statistically, around 11 million people were affected with CHD in 2017.1 2 Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation and secondary prevention (CR/SP) plays a crucial role in preventing the recurrence of CHD3 and has been listed as a class I recommendation for CHD treatment by the American Heart Association, the American Society of Cardiology and the European Society of Cardiology.4–7 The relevant guidelines recommend that patients with CHD should perform at least 500 Metabolic Equivalent (MET)-min/week physical activity every week.8 Although CR/SP have proven benefits, it is often challenging for patients to attain lifestyle changes needed for SP, especially with increasing physical activity levels.9 For example, owing to the poor accessibility of CR programmes, >80% of patients did not participate in the CR programmes recommended by the guidelines.10 Moreover, patients with CHD typically fail to attain their daily physical activity goals.11

Mobile health (mHealth), defined by American Heart Association’s scientific statement, ‘is the use of mobile computing and communication technologies (eg, mobile phones, wearable devices) for health services and information’,12 has become an essential medium to deliver behavioural change interventions and demonstrated promising ability to improve physical activity levels.12–14 For example, the Consumer Navigation of Electronic Cardiovascular Tools (CONNECT) trial examined the impact of digital health interventions on health behaviours and established the correlation between intervention and increased attainment of physical activity targets.15 In China, WeChat is a top-rated multipurpose social media app, with >1.151 billion active users.16 WeChat applets are lightweight apps that form part of the WeChat ecosystem, which could be used independently and do not need installation. Compared with mobile apps, WeChat applets are easier to be accepted and applied by people in China. The third quarter of 2019 recorded >300 million active WeChat applet users every day, thereby making it well suited to disseminate mHealth interventions in China.17

Gamification is the use of game design elements (such as points, leaderboards, progress bars and badges) in non-game contexts (such as management, education, marketing and healthcare) to increase motivation and engagement.18 There is growing interest in the application of gamification in mHealth with the view of promoting healthy behavioural changes,19–22 especially in promoting physical activity levels.23 Previous studies indicated that gamification was used in 64% of the top 50 most popular smartphone apps.24 However, several systematic reviews reported that most gamification intervention designs did not appropriately leverage theories from health behaviour models.19 25 26 Moreover, as the concept of gamification is relatively new,18 empirical evidence on the efficacy of gamification physical activity behavioural change interventions among patients with CHD is still emerging.

Gamification interventions are rarely based on a sound theoretical framework.20 22 Behavioural economics principles combine conventional economic principles with psychology to elucidate how individuals behave and make decisions.27 Behavioural economics principles can be embedded with a gamification intervention via mobile devices to aid people to attain their physical activity goals. For example, based on the loss aversion, which implies that the loss framework is more effective in stimulating behavioural change than the gain framework, Patel et al designed an intervention wherein participants lost points if they did not accomplish their step goals.28 Several previous studies have used behavioural economics principles to help patients lose weight, quit smoking and adhere to medications.29–31 However, limited data are available on applying these concepts to improve physical activity participation in patients with CHD.

This study will use behavioural economics principles to develop a gamification WeChat applet named ‘TahneeWeh’ to resolve the research gap mentioned above. This study aims to investigate the effects of the mHealth-based gamification intervention on participation in physical activity and evaluate the effects on biomedical and lifestyle-related risk factors, intrinsic motivation, enjoyment, competence, autonomy, and relatedness, social support, and mental health. In addition, a semi-structured interview will be conducted after the intervention to comprehend patients’ satisfaction, perceptions and their experience on the intervention.

Methods

Study design

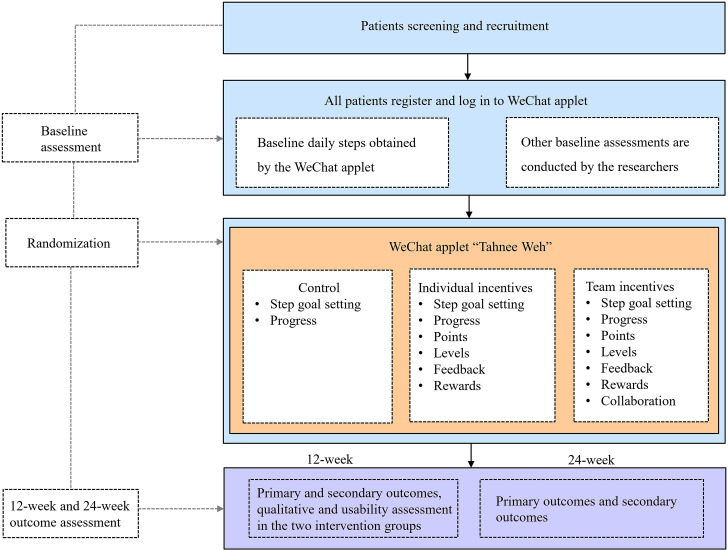

This is a single-blind, three-arm randomised controlled trial to evaluate the effects of the mHealth-based gamification intervention on participation in physical activity, biomedical and lifestyle-related risk factors, intrinsic motivation, enjoyment, competence, autonomy, and relatedness, social support, and mental health. Patients with CHD will be recruited in a CR centre of a tertiary-grade A class hospital in Changchun (China) through posters and email of discharged patients. A total of 108 participants will be randomly divided into three groups (Control group: WeChat applet+step goal setting; Individual group: WeChat applet+step goal setting+gamification; Team group: WeChat applet+step goal setting+gamification+collaboration). Patients in the control group will only receive daily step goal setting. The Individual and Team groups will receive gamified behaviour intervention based on behavioural economics principles. The Team group will also receive social incentives based on the Individual group. The intervention will last for 12 weeks and follow-up for 12 weeks. All patients will just receive WeChat applet-based step goal setting in the follow-up period. The study duration will be between 1 July 2021 and 30 November 2022. Figure 1 shows a flow chart of the study design. The protocol conforms to the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials reporting guidelines, and the intervention is described per the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials of Electronic and Mobile HEalth Applications and onLine TeleHealth(CONSORT-EHEALTH) checklist.32–34

Figure 1.

Study flow chart.

Eligibility and recruitment

Patients fulfilling the inclusion and exclusion criteria will be invited to participate in the trial. The inclusion criteria are as follows: (1) aged 18–70 years; (2) patients diagnosed with CHD (including acute myocardial infarction and unstable angina) and received percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) treatment during admission; (3) patients evaluated by cardiologists and rehabilitation therapists if they are suitable for participating in our programme; (4) patients willing to provide written informed consent; (5) patients with a smartphone and an active WeChat account; and (6) patients with proficiency in Chinese.

The exclusion criteria include the following: (1) contraindications for exercise rehabilitation (eg, untreated ventricular tachycardia, severe heart failure, uncontrollable hypertension or hypotension, notable exercise restriction); (2) patients unable to use WeChat applet after instruction; (3) no internet access in the place of residence; (4) patients requiring a walking aid to move and (5) patients participating in other clinical trials.

Experienced clinical nurses, rehabilitation therapists and researchers will be responsible for recruiting participants. Patients undergoing PCI will be referred to the CR centre, which is adjacent to the wards to receive physical activity counselling and obtain the follow-up booklet before discharge. The follow-up booklet will remind patients to return for review in 4 weeks, 12 weeks, 24 weeks and 12 months after discharge, which is very helpful to avoid patients’ lost to follow-up. In the rehabilitation centre, researchers will screen the eligible patients and then inform the patients about the details of the study. If they agree to participate in the study, they will have to sign the written consent form and complete the questionnaires using a traditional pen and paper method. We will mark the specific date of 12 and 24 weeks of his returning to complete the outcome measurement on his follow-up booklet and tell him if he is not available on that day; he could contact us to change the date accordingly. After that, we will teach patients to register and log in to our WeChat applet ‘TahneeWeh’; this is required to get their step data for the past 2 weeks, which will be recorded by smartphone accelerometers (as done in many prior studies35–38) and has been proven accurate for tracking step counts.39 Furthermore, a baseline step count will be estimated using the mean step count of the previous 2 weeks.

Sample size calculation

The main outcome indicator, daily step count, is selected as the calculation standard. Based on a previous study, we will ensure, at least, 90% power to detect an 800-step difference between each intervention arm and control, an SD of 2000 steps, and a two-sided α of 0.05.40 In addition, we will use one-way analysis of variance F-tests in PASS V.15.0.5 software and calculate that a total of 84 participants across three arms would be recruited. By allowing for an estimated 20% drop-out rate, a sample size of 108 will be used in this study.

Randomisation, blinding and concealed allocation

Patients will be randomised to a study arm using block sizes of 6, stratified by the participant baseline step count (<5000, 5001–7500, or >7500 steps/day). The data collector will be unaware of patient assignments at the baseline, 12 weeks and 24 weeks of the study. Researchers could see the assignments in the backstage of the WeChat applet, and the interfaces of the WeChat applet for patients in different groups are different.

Control

All patients will receive step goal setting and could see their progress on the WeChat applet during the 12-week intervention and 12-week follow-up. Personalised daily step goals will be set in the WeChat applet backstage based on patients’ baseline daily step counts, and the goals will increase gradually from the baseline by 15% each week during the first 6 weeks and then remain fixed during the last 6 weeks, as described elsewhere.41 To ensure the increase in physical activity is not harmful to participants, the rehabilitation therapists in our research group will assess the condition of each patient and make appropriate adjustments to the step goals. Participants could contact us at any time to make an adjustment if it is due to physical conditions. Moreover, patients could see their daily progress toward their goals using a circular dial on the WeChat applet. Of note, patients in the control group will receive no other interventions. If a patient does not log in to the WeChat applet for over a week, a text message reminder will be sent.

Intervention

Patients in the Individual and Team groups will receive the gamification intervention based on behavioural economics principles via the WeChat applet. Six behavioural economics principles (precommitment, fresh start effect, goal gradients, loss aversion, anticipated regret and social norms) will be embedded within the gamification intervention. The gamification intervention in the Individual group will apply to four game elements—feedback, points, levels and rewards. In the Team group, collaboration is added besides the four game elements mentioned above. Table 1 provides a summary of game elements, gamification intervention components, and behavioural economics principles.

Table 1.

A Summary of game elements, intervention components and behavioural economics (BE) principles

| Game elements | Gamification intervention components | BE principles |

| Patients will electronically sign a precommitment pledge to try their best to achieve their step goal. | Precommitment | |

| Points | Every Monday the patients will receive 140 points (20 for each day). | The fresh start effect |

| Points | If the patients reach the target step count, no points will be deducted; if not, 20 points will be deducted. | Loss aversion; anticipated regret |

| Collaboration | If the patient achieve the step goals and the other two people in her team also achieve the step goals, no points will be deducted; if the patient achieve the step goals but other two people in her team do not, 10 points for her team will be deducted; if neither the patient nor the other two people in her team does not achieve the step goal, 20 points will be deducted. | Social norms; loss aversion; anticipated regret |

| Levels | We set five levels, from low to high is bronze, silver, gold, platinum and diamonds. At the beginning of the trial, the patient is set to the gold level. If the patient has a total score of less than 80 points in a week, the level will drop, and if the total score is greater than or equal to 80 points, the level will rise. | the fresh start effect; goal gradients; loss aversion |

| Rewards | At the end of the intervention, if the patients’ level is diamond, they will be rewarded with a small prize. | |

| Feedback | Patients in the two intervention groups will receive feedback according to their progress weekly. |

Individual group

First, patients will electronically sign a precommitment pledge to try their best to attain their step goal. Precommitment is known to motivate behavioural change.42 43 Second, every Monday, patients will receive 140 points (20 for each day), which leverage the fresh start effect.44 Patients tend to be more driven for aspirational behaviour around temporal landmarks like the beginning of the week. Third, if patients reach the target step count, no points will be deducted; if not, 20 points will be deducted. This leverages loss aversion, demonstrating that loss framing is more effective at motivating behavioural change than gain framing.45 46 Fourth, a total of five levels will be set, from low to high—bronze, silver, gold, platinum and diamonds. At the beginning of the trial, patients will be set to the gold level. If a patient has a total score of <80 points in the week, the level will drop, and if the total scores are ≥80 points, the level will increase; this is done such that the patients would feel their level dropping to silver if they did not attain sufficient points in the first week. At the end of the intervention, if the level of a patient is diamond, he/she will be rewarded with a small prize. Fifth, patients in the two intervention groups will receive feedback weekly based on their progress.

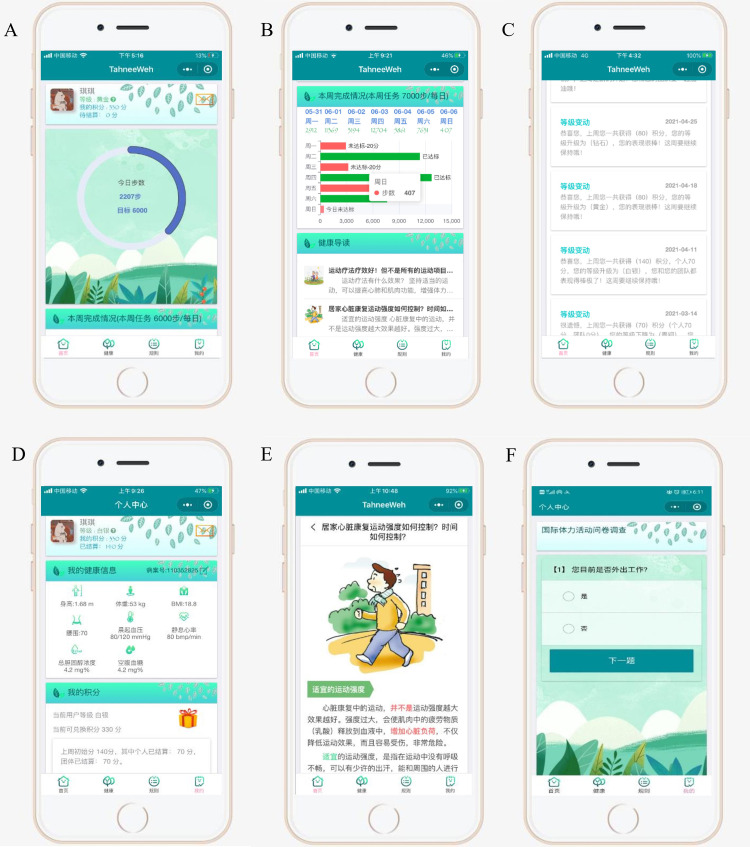

Team group

The team group will also receive social incentives based on the Individual group. Patients are assigned to a team of three people, who do not know each other before the intervention. Every Monday, the patients will receive 140 points (20 for each day, 10 for themselves, 10 for their team). If the patient achieves the step goals and the other two people in his/her team also achieve the step goals, no points will be deducted. If the patient achieves the step goals, but other two people in his/her team do not, 10 points for their team will be deducted. If neither the patient nor the other two people in his/her team achieve the step goal, 20 points will be deducted. Figure 2 presents the WeChat applet interface, and figure 3 shows the backstage management system of the WeChat applet.

Figure 2.

Wechat applet ‘TahneeWeh’ interface. (A) Daily step progress using a circular dial; (B) weekly step progress; (C) feedback on Weekly level changes; (D) points and level in this week; (E) health education on cardiac rehabilitation and secondary prevention; (F) International Physical Activity Questionnaire filling interface.

Figure 3.

The backstage management system of the WeChat applet ‘TahneeWeh’.

Outcome measures and data collection

Patients recruited in the trial will be asked to complete the questionnaires and outcome measurements in the CR clinic when they return to hospital for a review. The WeChat applet will automatically remind patients to complete the outcome measurements in 12 and 24 weeks. If the patient does not return on time, researchers will telephonically inquire about the reasons. We will also report the numbers and reasons of patients lost to follow-up.

Table 2 shows the summary of the outcome measures for the study. The primary outcome is physical activity participation, which includes a change in daily steps and self-reported physical activity from the baseline to 12 and 24 weeks, and the proportion of patient-days that step goals achieved in 12 and 24 weeks. The daily step counts will be measured and recorded by smartphone accelerometers, proven accurate for tracking step counts.39 Self-reported physical activity level will be measured by the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ).47

Table 2.

Assessment time points for primary and secondary outcomes

| Outcome | Assessment | Baseline | 12 weeks | 24 weeks |

| Primary outcomes | ||||

| Physical activity | Change in daily steps | √ | √ | √ |

| The proportion of patient-days that step goals were achieved | √ | √ | ||

| International Physical Activity Questionnaire47 | √ | √ | √ | |

| Secondary outcomes | ||||

| Biomedical risk factors | Body weight, waist circumference, BMI, SBP, DBP, RHR | √ | √ | √ |

| Lifestyle-related risk factors | Self-reported smoking | √ | √ | √ |

| Competence, autonomy and relatedness | Psychological Needs Satisfaction in Exercise Scale52 | √ | √ | √ |

| Intrinsic motivation | Behavioural Regulation in Exercise Questionnaire53 | √ | √ | √ |

| Enjoyment | Physical Activity Enjoyment Scale54 | √ | √ | √ |

| Social support | Social Support Rating Scale55 | √ | √ | √ |

| Anxiety symptoms | Generalised Anxiety Disorder 7-item Scale56 | √ | √ | √ |

| Depressive symptoms | Patient Health Questionnaire57 | √ | √ | √ |

| Usability | System Usability Scale48 | √ | ||

| Satisfaction | Semistructured interview | √ | ||

| Patients’ experience | Semistructured interview | √ | ||

| Adverse event reporting | Medical occurrences resulting in hospitalisation, disability or deaths |

BMI, body mass index; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; RHR, resting heart rate; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

The secondary outcomes include biomedical risk factors, which include the body weight (kg), waist circumference (cm), body mass index (BMI), systolic blood pressure (mm Hg), diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg), resting heart rate (bpm/min), lifestyle-related risk factors, including smoking, intrinsic motivation, enjoyment, competence, autonomy, and relatedness, social support, anxiety symptom, and depressive symptoms. The IPAQ will be filled out online at the baseline,12 weeks and 24 weeks through the WeChat applet, while the other measurements will be taken in the hospital (at the baseline, 12 weeks and 24 weeks). In addition, usability will be tested at the end of the intervention (at 12 weeks) in the two intervention groups using the System Usability Scale.48 Furthermore, we will conduct a semi-structured interview to understand patients’ satisfaction, perceptions and experiences in the two intervention groups.

All adverse events will be reported to the ethics committee as required during the 24 weeks study period. Adverse events are defined as medical occurrences resulting in hospitalisation, disability or death.

Statistical analysis and data management

All continuous variables will be reported as mean and SD, and categorical variables will be described as frequencies and percentages. Within-group changes in daily step counts, the proportion of patient-days that step goals attained, self-reported physical activity, biomedical and lifestyle-related risk factors, intrinsic motivation, enjoyment, competence, autonomy, and relatedness, social support, and mental health will be compared using a paired t-test or Wilcoxon rank-sum test depending on the data distribution. Besides, a one-way analysis of variance will be used to compare the intergroup differences between the baseline and postintervention among the outcomes. Main analysis and secondary analysis will be conducted of all the outcomes. In the main analysis, the analysis of outcomes will be conducted per the intention-to-treat principle. In addition, multiple imputations for data will be used that are missing and with step values <1000 because evidence indicates that these values are unlikely to represent the capture of actual activity.37 49 In the secondary analysis, data analysis will be conducted without multiple imputations, both with and without step values<1000. Furthermore, adjusted analyses include sex, age, BMI, severity of disease and baseline variables. Moreover, we will compare the baseline differences between patients lost to follow-up and patients who adhere to follow-up. All statistical analyses will be two sided, and p<0.05 will be considered statistically significant. We will use SPSS V.20.0 for data analysis.

In this study, well-trained clinical researchers will record all patients’ data using standardised case report forms (CRFs). The original data will be recorded timely and accurately, and a copy of the report will be kept in the laboratory. All CRFs will be stored in a locked file cabinet to prevent data leakage. All laboratory data will be identified with a code number to ensure the confidentiality of subjects’ data. The clinical research data management platform of the School of Nursing of Jilin University will be accountable for data monitoring. The chief investigator can directly access the dataset, and the data scattered to the project team members cannot identify any participant identity information.

Patient and public involvement

Patient and public involvement (PPI) played a vital role in this study. Before designing the WeChat applet, the authors conducted a survey among patients with CHD and found that patients lacked physical activity and were willing to be supervised and motivated via their smartphones to promote participation in physical activity. During the development of WeChat applet, patients with CHD will be invited to participate in our discussion, allowing the authors to consider the thoughts and needs of patients in developing the WeChat applet. In the pilot study, patients will be invited to give reasonable recommendations for study design, questionnaire selection and outcome measurements while considering the burden of intervention. The results of this study will be disseminated to PPI representatives and study participants who wish to be notified.

Validity and reliability

This study will use a rigorous research design (randomised controlled design) and a block random method to assign groups. The grouping results will be numbered and placed in a sealed envelope. Participants and data collectors will be blinded to the assignments. All questionnaires will be completed by the researcher’s guidance or ghostwriting. The questionnaires will be distributed and collected on the spot to avoid data bias caused by different researchers. Two researchers will enter all the data to avoid objective typing errors.

Ethics and dissemination

This study will comply with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, and the Human Research Ethics has been approved by the School of Nursing, Jilin University (HREC 2020122401). All participants will be required to provide written informed consent. Research reports will be disseminated through scientific forums, including peer-reviewed publications and presentations at national and international conferences.

Discussion

The authors aim to develop a WeChat applet in this study. Based on the WeChat applet and under the guidance of behavioural economics principles, the authors will develop a gamification intervention using five game elements, including points, levels, feedback, rewards and collaboration. This study will evaluate the role of mHealth-based gamification intervention on physical activity participation and the effects on biomedical and lifestyle-related risk factors, intrinsic motivation, enjoyment, competence, autonomy, and relatedness, social support, and mental health. Moreover, the authors will conduct a semi-structured interview after the intervention to elucidate patients’ satisfaction, perceptions and experience of the intervention.

Despite proven benefits, patients with CHD do not often attain their physical activity goals on their own.11 Behavioural interventions are needed to help them increase physical activity participation. With technological advancement, numerous smartphone apps have appeared, and gamification was used in most of these apps, which could increase physical activity motivation and promote behavioural change. However, most gamification intervention designs did not appropriately leverage theories from health behaviour models, and empirical evidence on their efficacy is still emerging. A previous study established that behavioural economics principles could be embedded with a gamification intervention to significantly increase physical activity among overweight and obese adults.28 However, thus far, there is limited evidence of interventions that use these methods to effectively improve physical activity participation among high-risk patients, such as patients with CHD.50 Thus, this study will develop a gamification intervention based on a WeChat applet that has been specifically developed for this study. Personalised goal setting and progress tracking on the WeChat applet will allow patients to exercise under supervision. The gamification intervention motivated patients to walk more; this could become a new way to promote the implementation of home and exercise-based CR.

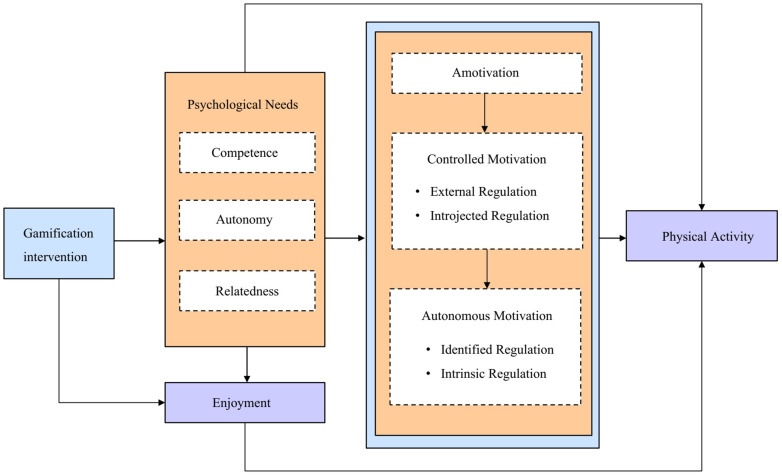

The key of gamification interventions is to organically combine game elements to form a resultant force to improve physical activity, and the key of the resultant force is to comprehend the driving force or motivation behind the incentive mechanism. Research indicates links between self-determination theory and gamification concepts. Self-determination theory suggests that satisfying three innate psychological needs of competence, autonomy and relatedness could promote autonomous motivation and well-being. Reportedly, individuals with autonomous motivation had higher physical activity participation and better physical activity adherence than those primarily driven by external factors.51 Furthermore, the fact that gamification could make interventions more enjoyable aligns with self-determination theory, which assumes that a key aspect of intrinsic motivation is enjoyment.18 We plan to investigate the internal psychological mechanism of gamification to promote physical activity; thus, we will evaluate competence, autonomy, relatedness, enjoyment and intrinsic motivation. We assume that gamification intervention promotes the transformation of controlled motivation into autonomous motivation by satisfying competence, autonomy, relatedness, enjoyment and ultimately promote physical activity participation. Figure 4 shows the hypothesised model of physical activity behaviour regulation. Moreover, because our intervention platform will provide information support for patients, we will also evaluate the variable social support. Furthermore, we will conduct a semi-structured interview after the intervention to comprehend patients’ experiences and capture information on communications among patients in the collaboration group, which could explore the internal psychological mechanism of gamification to promote exercise motivation.

Figure 4.

The hypothesised model of physical activity behaviour regulation.

In China, access to CR is often limited. Patients with CHD often lack physical activity. Our intervention could help increase physical activity participation and bring more health benefits.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, we will not measure the intensity of physical activity via the smartphone accelerometer. In future, we plan to use wearable devices to evaluate the intensity of physical activity. Second, the study is limited to patients with smartphones and a WeChat account, which could lead to a selective bias. Third, the gamification interventions are comprehensive, and it would be difficult to analyse the component that worked. Fourth, it is a multilayered and complex intervention, and the projected sample size will make it challenging to say that the results will be much more than a pilot study given there will be three groups.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the valuable contribution made by the patients and public representatives during the study design and intervention development.

Footnotes

QT and FL contributed equally.

Contributors: LX, QT and FL conceived the original concept of the study and wrote the first draft of the protocol manuscript. LX, JL, XZ, YP, TY, XL, TY and LZ contributed to the design of the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work is financially supported by a Construction Programme of Independent Innovation Ability of Community Health Nursing Engineering Laboratory in Jilin Province (Study code: 2020C038-8) awarded to FL.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer-reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Consent obtained directly from patient(s)

References

- 1. Zhou M, Wang H, Zeng X, et al. Mortality, morbidity, and risk factors in China and its provinces, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet 2019;394:1145–58. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30427-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chen W, Gao R, Liu L. China cardiovascular disease report 2017. Chinese J Circ 2018;33:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Thomas RJ, King M, Lui K, et al. AACVPR/ACC/AHA 2007 performance measures on cardiac rehabilitation for referral to and delivery of cardiac rehabilitation/secondary prevention services. Circulation 2007;116:1611–42. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.185734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Leon AS, Franklin BA, Costa F, et al. Cardiac rehabilitation and secondary prevention of coronary heart disease: an American heart association scientific statement from the Council on clinical cardiology (Subcommittee on exercise, cardiac rehabilitation, and prevention) and the Council on nutrition, physical activity, and metabolism (Subcommittee on physical activity), in collaboration with the American association of cardiovascular and pulmonary rehabilitation. Circulation 2005;111:369–76. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000151788.08740.5C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Corr U, European Association of Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation Committee for Science Guidelines; EACPR . Secondary prevention through cardiac rehabilitation: physical activity counselling and exercise training key components of the position paper from the Cardiac Rehabilitation Section of the European Association of Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation. Eur Heart J 2010;31:1967–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fletcher GF, Ades PA, Kligfield P, et al. Exercise standards for testing and training: a scientific statement from the American heart association. Circulation 2013;128:873–934. 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31829b5b44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chinese Society of cardiovascular diseases, Chinese Society of rehabilitation medicine, cardiovascular diseases Committee of Chinese Society of rehabilitation medicine, cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases Committee of Chinese Society of gerontology. Chinese expert consensus on coronary heart disease rehabilitation and secondary prevention (2013). Chinese Journal of Cardiovascular Diseases 2013;41:267–75. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Stewart RAH, Held C, Hadziosmanovic N, et al. Physical activity and mortality in patients with stable coronary heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;70:1689–700. 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.08.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shore S, Jones PG, Maddox TM, et al. Longitudinal persistence with secondary prevention therapies relative to patient risk after myocardial infarction. Heart 2015;101:800–7. 10.1136/heartjnl-2014-306754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Thomas RJ. Cardiac rehabilitation/secondary prevention programs: a raft for the rapids: why have we missed the boat? Circulation 2007;116:1644–6. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.728402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kronish IM, Diaz KM, Goldsmith J, et al. Objectively measured adherence to physical activity guidelines after acute coronary syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;69:1205–7. 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.10.087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Burke LE, Ma J, Azar KMJ, et al. Current science on consumer use of mobile health for cardiovascular disease prevention: a scientific statement from the American heart association. Circulation 2015;132:1157–213. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. McConnell MV, Turakhia MP, Harrington RA, et al. Mobile health advances in physical activity, fitness, and atrial fibrillation: moving hearts. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;71:2691–701. 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.04.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Coorey GM, Neubeck L, Mulley J, et al. Effectiveness, acceptability and usefulness of mobile applications for cardiovascular disease self-management: systematic review with meta-synthesis of quantitative and qualitative data. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2018;25:505–21. 10.1177/2047487317750913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Redfern J, Coorey G, Mulley J, et al. A digital health intervention for cardiovascular disease management in primary care (connect) randomized controlled trial. NPJ Digit Med 2020;3:117. 10.1038/s41746-020-00325-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. CIW Team . WeChat statistical highlights 2020; mini program DAU >300m. China Internet Watch. 2020 May 18. Available: https://www.chinainternetwatch.com/30201/wechat-stats-2019/ [Accessed 2020-07-18].

- 17. Zhang X, Wen D, Liang J, et al. How the public uses social media WeChat to obtain health information in China: a survey study. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2017;17:66. 10.1186/s12911-017-0470-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Deterding S, Dixon D, Khaled R, et al. From game design elements to gamefulness: defining gamification (2011). 2011 Presented at: Proceedings of the 15th International Academic MindTrek Conference; 2011, Tampere, Finland:p. 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sardi L, Idri A, Fernández-Alemán JL. A systematic review of gamification in e-health. J Biomed Inform 2017;71:31–48. 10.1016/j.jbi.2017.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lister C, West JH, Cannon B, et al. Just a FAD? Gamification in health and fitness apps. JMIR Serious Games 2014;2:e9. 10.2196/games.3413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. King D, Greaves F, Exeter C, et al. 'Gamification': influencing health behaviours with games. J R Soc Med 2013;106:76–8. 10.1177/0141076813480996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Johnson D, Deterding S, Kuhn K-A, et al. Gamification for health and wellbeing: a systematic review of the literature. Internet Interv 2016;6:89–106. 10.1016/j.invent.2016.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gamification for physical activity behaviour change. Perspect Public Health 2018;138:309–10. 10.1177/1757913918801447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cotton V, Patel MS. Gamification use and design in popular health and fitness mobile applications. Am J Health Promot 2019;33:448–51. 10.1177/0890117118790394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Edwards EA, Lumsden J, Rivas C, et al. Gamification for health promotion: systematic review of behaviour change techniques in smartphone apps. BMJ Open 2016;6:e012447. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hamari JKJ, Sarsa H. Does gamification work?-A literature review of empirical studies on gamification. Paper presented at: 47th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences; January 6-9, 2014, Hawaii, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Shuval K, Leonard T, Drope J, et al. Physical activity counseling in primary care: insights from public health and behavioral economics. CA Cancer J Clin 2017;67:233–44. 10.3322/caac.21394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Patel MS, Small DS, Harrison JD, et al. Effectiveness of behaviorally designed Gamification interventions with social incentives for increasing physical activity among overweight and obese adults across the United States: the step up randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 2019;179:1624–32. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.3505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Volpp KG, John LK, Troxel AB, et al. Financial incentive-based approaches for weight loss: a randomized trial. JAMA 2008;300:2631–7. 10.1001/jama.2008.804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Volpp KG, Loewenstein G, Troxel AB, et al. A test of financial incentives to improve warfarin adherence. BMC Health Serv Res 2008;8:272. 10.1186/1472-6963-8-272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Writing Group Members, Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, et al. Heart disease and stroke Statistics-2016 update: a report from the American heart association. Circulation 2016;133:e38–60. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chan A-W, Tetzlaff JM, Altman DG, et al. Spirit 2013: new guidance for content of clinical trial protocols. The Lancet 2013;381:91–2. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62160-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chan A-W, Tetzlaff JM, Altman DG, et al. Spirit 2013 statement: defining standard protocol items for clinical trials. Ann Intern Med 2013;158:200–7. 10.7326/0003-4819-158-3-201302050-00583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Chan A-W, Tetzlaff JM, Gøtzsche PC, et al. Spirit 2013 explanation and elaboration: guidance for protocols of clinical trials. BMJ 2013;346:e7586. 10.1136/bmj.e7586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Althoff T, Jindal P, Leskovec J. Online actions with offline impact: how online social networks influence online and offline user behavior. Proc Int Conf Web Search Data Min 2017;2017:537-546. 10.1145/3018661.3018672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Althoff T, White RW, Horvitz E. Influence of Pokémon go on physical activity: study and implications. J Med Internet Res;2016:e315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bassett DR, Wyatt HR, Thompson H, et al. Pedometer-measured physical activity and health behaviors in U.S. adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2010;42:1819–25. 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181dc2e54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tudor-Locke C, Craig CL, Brown WJ, et al. How many steps/day are enough? for adults. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2011;8:79. 10.1186/1479-5868-8-79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Case MA, Burwick HA, Volpp KG, et al. Accuracy of smartphone applications and wearable devices for tracking physical activity data. JAMA 2015;313:625–6. 10.1001/jama.2014.17841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Harrison JD, Jones JM, Small DS, et al. Social incentives to encourage physical activity and understand predictors (step up): design and rationale of a randomized trial among overweight and obese adults across the United States. Contemp Clin Trials 2019;80:55–60. 10.1016/j.cct.2019.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Chokshi NP, Adusumalli S, Small DS. Loss-Framed financial incentives and personalized Goal-Setting to increase physical activity among ischemic heart disease patients using wearable devices: the active reward randomized trial. J Am Heart Assoc;2018:e009173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ariely D, Wertenbroch K, Procrastination WK. Procrastination, deadlines, and performance: self-control by precommitment. Psychol Sci 2002;13:219–24. 10.1111/1467-9280.00441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rogers T, Milkman KL, Volpp KG. Commitment devices: using initiatives to change behavior. JAMA 2014;311:2065–6. 10.1001/jama.2014.3485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Dai H, Milkman KL, Riis J. The fresh start effect: temporal landmarks motivate aspirational behavior. Manage Sci 2014;60:2563–82. 10.1287/mnsc.2014.1901 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Patel MS, Asch DA, Rosin R, et al. Framing financial incentives to increase physical activity among overweight and obese adults: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 2016;164:385–94. 10.7326/M15-1635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kahneman D, Tversky A. Prospect theory: an analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica 1979;47:263. 10.2307/1914185 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjöström M, et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2003;35:1381–95. 10.1249/01.MSS.0000078924.61453.FB [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Brooke J. SUS: a “quick and dirty” usability scale. In: Jordan PW, Thomas B, Weerdmeester BA, et al., eds. Usability evaluation in industry. London: Taylor and Francis, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kang M, Rowe DA, Barreira TV, et al. Individual information-centered approach for handling physical activity missing data. Res Q Exerc Sport 2009;80:131–7. 10.1080/02701367.2009.10599546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Romeo A, Edney S, Plotnikoff R, et al. Can smartphone Apps increase physical activity? Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res 2019;21:e12053. 10.2196/12053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Dacey M, Baltzell A, Zaichkowsky L. Older adults' intrinsic and extrinsic motivation toward physical activity. Am J Health Behav 2008;32:570–82. 10.5993/AJHB.32.6.2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Wilson PM, Rogers WT, Rodgers WM, et al. The psychological need satisfaction in exercise scale. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology 2006;28:231–51. 10.1123/jsep.28.3.231 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Markland D, Tobin V. A modification to the behavioural regulation in exercise questionnaire to include an assessment of Amotivation. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology 2004;26:191–6. 10.1123/jsep.26.2.191 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kendzierski D, DeCarlo KJ. Physical activity enjoyment scale: two validation studies. J Sport Exerc Psychol 1991;13:50–64. 10.1123/jsep.13.1.50 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Wang XD. Manual of Mental Health Rating Scale M. Updated edition. Beijing: China Mental Health Magazine, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1092–7. 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001;16:606–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.