Abstract

Introduction

Haemophilia is a hereditary, chronic and haemorrhagic disorder caused by a deficiency in coagulation factors. Long-term spontaneous bleeding of joints and soft tissues can seriously affect the quality of life of patients.

Objective

The study aimed to assess the health-related quality of life (HRQoL) of patients with haemophilia and associated factors.

Methods

A snowball sampling strategy was adopted to select study participants. Eligible participants were those who were 18 years or older and had mild, moderate or severe haemophilia. They were asked to self-complete a questionnaire, collecting data regarding their sociodemographic characteristics, target joint status and HRQoL measured by the EQ-5D-5L(a tool developed by the European quality of life (EuroQol) Group).

Results

The respondents reported a mean EQ-5Dutility(country-specific valuesets for the EQ-5D-5L) score of 0.51 (SD=0.34). Those with severe haemophilia had a lower utility score than those with mild/moderate haemophilia (0.46±0.37 vs 0.56±0.30, p=0.737). The linear regression analyses showed that older age (>25 years), two or more target joints, not working, low levels of knowledge of the disease and borrowing money to pay for medical treatments were associated with lower EQ-5Dutility scores.

Conclusion

Low HRQoL of patients with haemophilia is evident in China. Social support needs to be strengthened to address this issue.

Keywords: bleeding disorders & coagulopathies, health & safety, public health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A snowball sampling strategy was adopted to recruit participants. Data were collected through the online survey platform Wenjuanxing from July to August 2019.

The EQ-5Dutility index and Visual Analogue Scale scores were transformed into a normal distribution using the Blom case rank method, before a multivariate linear regression model was established.

Content analyses were performed for the open-ended question.

Selection bias of the study sample is likely to occur as this study adopted a snowball sampling strategy.

The online survey might have excluded the patients who did not have good access to the internet.

Introduction

Haemophilia is a genetic disease in which patients develop severe blood coagulation disorders due to a lack of certain clotting factors in blood (decrease or absence of coagulation factor Ⅷ (haemophilia A) or factor Ⅸ (haemophilia B)).1 Haemophilia A accounts for approximately 85% of the haemophilia cases.2 Both haemophilia A and B can be classified into three levels, depending on the coagulation factor activity: mild, moderate and severe.3 The patients usually suffer from spontaneous haemorrhage of joints, muscles and soft tissues. About 80% of the bleeding events occur in the knee, elbow and ankle joints. Repeated joint bleeding can result in deformation of the joints (labelled as target joints), hemophilic arthropathy and disability,4 seriously jeopardising the quality of life of the patients.5 Haemophiliacs have significantly lower health-related quality of life (HRQoL) than the general population.6 7 More target joints are associated with lower HRQoL.8 Patients with haemophilia were also exposed to high risks of hepatitis prior to the 1990s in China, which can further worsen their HRQoL.9

Haemophilia is a rare chronic disease.10 A systematic review and meta-analysis revealed a prevalence of 2.7/100 000 for haemophilia (A and B combined) in Mainland China. It was estimated that about 37 600 patients with haemophilia live in China.11 However, the officially registered number of haemophilia in mainland China to the World Federation of Haemophilia (WFH) is only half of the estimated number: 18 712 in total, including 16 158 haemophilia A and 2460 haemophilia B (some cases recorded unknown type). The patients in mainland China appear to receive a much lower level of factor Ⅷ (0.026 IU) compared with those in Sweden (10.134 IU), the USA (9.964 IU) and Canada (8.151 IU).12

Internationally, there have been increasing concerns about the poor HRQoL of people living with haemophilia.13 Researchers believe that HRQoL as a patient-reported outcome is more closely related to survival of patients.14 Adequate diagnoses and treatments can significantly improve the HRQoL of patients with haemophilia and prolong their life span.15 However, combined with the number of haemophiliacs reported to WFH in China and the estimated number of patients based on the incidence, about 50% of patients in China have not been properly diagnosed or treated.

Measuring HRQoL of patients with haemophilia is not only meaningful for informing clinical decisions but also important for developing policies and mobilising healthcare resources as a society.13 HRQoL is usually considered as the most important goal for managing haemophilia. HRQoL data can be benchmarked across countries to determine the appropriateness of patient management. These data can also be used in cost-effectiveness and cost–utility analyses, which are required to inform policy decisions on resource allocations.

There is a dearth in the literature documenting HRQoL of patients with haemophilia in China. With the world’s largest population, China has the largest number of patients with haemophilia. Previous studies have shown that patients with haemophilia in China do not always have access to prophylaxis, the essential medicine to prevent and control bleeding, due to financial and resource barriers,16 which may result in low HRQoL in comparison with the patients living in the Western countries.13 17 This study aimed to fill the gap in the literature through a cross-sectional survey on the HRQoL of patients with haemophilia living in Heilongjiang Province of China.

Methods

Study setting

A questionnaire survey of 154 patients with haemophilia was conducted in Heilongjiang Province of China. Heilongjiang is located in northeastern of China with a population of 37.51 million. It was estimated that Heilongjiang has about 1000 patients with haemophilia (a prevalence of 2.9 per 100 000 population).11 Heilongjiang is ranked in the lower range of socioeconomic development in China. The Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita in Heilongjiang reached US$5174.96 in 2019,18 falling into the range of middle-income economies according to the criteria of the United Nations.19

Sampling

A snowball sampling strategy was adopted to recruit study participants as haemophilia is a rare disease.20 A small number of patients with haemophilia were identified first with the help of the haemophilia advocacy group. Those who were willing to participate in this study were asked to invite other patients they knew to complete the questionnaire. Eligible participants included those who were male and aged over 18 years and had a clinical diagnosis of haemophilia A or B. Those who were not able to read and understand the questionnaire in Chinese were excluded from the survey.

In China, patients with haemophilia who had a confirmed diagnosis tended to obtain treatments from a limited number of medical centres as the vast majority of health institutions did not provide such services. Thanks to the availability of modern information technologies, patients with haemophilia were able to establish a self-help group via the WeChat platform, involving members across the entire Heilongjiang Province. This was a very close-knit group championed by patients with haemophilia themselves. Members could be invited by the patients and their caregivers, as well as health workers. The group could not only share knowledge and information via the platform but also seek answers to questions from medical professionals. It was estimated that more than 71% of Chinese residents had access to WeChat in 2018.

Patient and public involvement

After completing the questionnaire design, Dong, the president of Heilongjiang Blood Friends Home conducted a preliminary review, revised inaccurate and inappropriate words, and designed the questionnaire from the perspective of patients. The revised questionnaire was sent to Dong in the form of an online link, and the president sent the questionnaire to the Wechat patient group in Heilongjiang Province, and the sample size was expanded by using the patient–patient snowball sampling method. The results would be disseminated, through Dong, to the patient groups.

Data collection

Data were collected from July to August 2019 through the online survey platform Wenjuanxing (https://www.wjx.cn/). An invitation letter was sent out to the WeChat group of haemophilia with a link to the platform. The questionnaire started with an introduction of the purpose and procedure of the survey. Those who agreed with the terms and met the inclusion criteria were invited to proceed to the questionnaire. The survey was voluntary and anonymous. Submission of the questionnaire was deemed informed consent.

Two trained researchers reviewed the submitted questionnaires independently. The questionnaires with inconsistencies and those with over 20% missing answers were excluded from the final sample for data analyses. In total, 154 eligible patients submitted the questionnaire, which accounted for about 15.4% of all patients diagnosed with haemophilia in Heilongjiang. Four questionnaires were excluded after the independent review. This final sample size was 150, which was deemed large compared with similar studies conducted elsewhere.20

Measurements and variables

The questionnaire contained four sections measuring (1) sociodemographic characteristics, (2) symptoms and conditions of haemophilia, (3) haemophilia-related knowledge and (4) HRQoL of the patients. Item descriptions of the questionnaire considered limitations of health literacy of the patients with haemophilia in Heilongjiang. The clinical concepts were explained in lay languages. For example, ‘target joints’ was explained as the joints that had bled three or more times over a 6-month period. The patients were asked to look at their test results of coagulation factor for the purpose of severity classification: a less than 1% concentration was deemed severe, compared with 1%–5% as moderate, and >5% and<40% as normal. Further details of the questionnaire are attached as a supplementary file (online supplemental file 1).

bmjopen-2021-056668supp001.pdf (459.2KB, pdf)

According to the ecosocial theory,21 the HRQoL of patients with haemophilia is shaped by the social and physical environments in which biology factors and individual behaviours interact with each other. In this study, three broad categories of HRQoL determinants in line with the ecosocial theory were examined. These included the clinical features of the disease and treatments received by the patients, the knowledge and strategies adopted by the patients in managing the disease, and the socioeconomic environment of the patients. Researchers believe that HRQoL is a function of the direct and indirect effects of social structure and a combination of objective and subjective factors.22

Sociodemographic characteristics

Those measured included age, educational attainment, marital status, family history and residency (urban vs rural). The study did not measure household income because great disparities exist in living standards across regions in Heilongjiang and the estimation of income is often unreliable.23 Instead, residency status served as a proxy indicator. In China, rural residents usually have a lower income than their urban counterparts and enjoy lower levels of welfare entitlements including social health insurance.24 The respondents were also asked to report whether they had ever borrowed money to get access to the treatments for haemophilia.

Symptoms and conditions of haemophilia

Six aspects were assessed, including the count of target joint parts, presence of inhibitory antibody, severity of the condition, treatments received (prophylaxis vs on-demand treatment), body mass index (BMI) and comorbidity with hepatitis. A target joint was defined as one that had bled three or more times over a 6-month period.25 In this study, the location of target joints was categorised into upper body (neck, shoulder, elbow and wrist) and lower body (hip, knee and ankle).8 Severity of the condition was assessed by the level of activity of the coagulation factors and was classified into mild (>5% and <40% of normal level), moderate (1%–5% of normal level) and severe (<1% of normal level) conditions.26 Regular infusion of prophylaxis can stabilise the coagulation factors for a certain period of time to prevent bleeding.20 However, if bleeding occurs, ‘on-demand treatment’ would be given to the patients through injection of the clotting factors. BMI was estimated by asking the patients to report their body weight (kg) and height (m). A BMI of <18.5 kg/m2 was considered underweight and >24.9 kg/m2 was deemed overweight or obese.27

Haemophilia-related knowledge

Four questions were designed by the research team, assessing the level of knowledge of the patients regarding the genetic origin, pathogenesis, care and management of haemophilia. A positive answer was given a score of 1, otherwise 0. A summed score was calculated for each respondent, with a higher score indicating a high level of knowledge. A knowledge score of 3 or lower was considered low, while a full mark of 4 was deemed high.

HRQoL

This part was measured using the EQ-5D-5L, a generic preference-based instrument developed by an international team.28 It has been used for assessing patient-reported health outcomes in various clinical settings.29 The EQ‐5D‐5 L measures problems experienced by the respondents in five aspects: mobility (MO), self‐care (SC), usual activities (UA), pain/discomfort (PD) and anxiety/depression (AD). Compared with its predecessor the EQ-5D-3L, the increased level of alternative answers generated less ceiling and floor effects and higher reliability and sensitivity.30 This study adopted the validated Chinese version of the EQ-5D-5L.31 An EQ-5Dutility index was calculated for each respondent using the value set (ranging from −0.39 to 1.00 (‘worse than death’) to 1 (‘absence of problems’) recently developed in China.32 The EQ-5D-5L also includes a Visual Analogue Scale (VAS), measuring the overall health of the respondents on a scale ranging from 0 (worst imaginable health state) to 100 (best imaginable health state).

The respondents were also asked to describe how haemophilia affected their quality of life through an open-ended question.

Statistical analysis

The sociodemographic characteristics and other basic information were described using frequency analyses categorised by the severity of haemophilia.

The EQ-5Dutility index and VAS scores were transformed into a normal distribution using the Blom case rank method33 before a multivariate linear regression model was established for the normalised utility index and VAS scores, respectively. An enter approach was adopted for the modelling. The multicollinearity of the independent variables was assessed through VIF(Variance Inflation Factor) and tolerance. No significant collinearity was found (tolerance >0.2 and VIF <10).

All of the statistical analyses were performed using the Statistics Package for Social Science V.24.0. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Content analyses were performed for the open-ended question. General themes were extracted and coded using NVivo V.10.0.

Results

Characteristics of participants

The respondents had an average age of 34.13 years. The majority were not married (64.67%) at the time of the survey and resided in urban areas (71.33%). Less than 37% completed high school education.

Most (88.67%) patients had haemophilia A. Slightly less than half (48.67%) were classified as mild/moderate. Only 12.67% patients did not report any target joint. About 42% were overweight/obese. Most patients (83.77%) had on-demand treatment over the past year (table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of study participants (n=150)

| Characteristics | Participants, n (%) | ||||

| Total | Mild/moderate patients | Severe patients | P value | ||

| Sociodemographic | |||||

| Age (years) | <25 | 37 (24.67) | 16 (21.92) | 21 (27.27) | 0.750 |

| 25–29 | 19 (12.66) | 8 (10.99) | 11 (14.29) | ||

| 30–34 | 25 (16.67) | 13 (17.81) | 12 (15.58) | ||

| ≥35 | 69 (46.00) | 36 (49.32) | 33 (42.86) | ||

| Marital status | Unmarried | 97 (64.67) | 40 (54.79) | 57 (74.03) | 0.014 |

| Married | 53 (35.33) | 33 (45.21) | 20 (25.97) | ||

| Educational attainment | Illiterate | 10 (6.67) | 4 (5.48) | 6 (7.79) | 0.812 |

| Middle school | 85 (56.67) | 41 (56.16) | 44 (57.14) | ||

| High school | 55 (36.67) | 28 (38.36) | 27 (35.06) | ||

| Employment | Employed | 23 (15.33) | 12 (16.44) | 11 (14.29) | 0.604 |

| Leave of absence | 121 (80.67) | 57 (78.08) | 64 (83.12) | ||

| Unemployed | 6 (4.00) | 4 (5.48) | 2 (2.60) | ||

| Residency | Urban | 107 (71.33) | 50 (68.49) | 57 (74.03) | 0.454 |

| Rural | 43 (28.67) | 23 (31.51) | 20 (25.97) | ||

| Disease condition | |||||

| Type | Haemophilia A | 133 (88.67) | 64 (87.67) | 69 (89.61) | 0.708 |

| Haemophilia B | 17 (11.33) | 9 (12.33) | 8 (10.39) | ||

| Target joint | Yes | 131 (87.33) | 60 (82.19) | 71 (92.21) | 0.065 |

| No | 19 (12.67) | 13 (17.81) | 6 (7.79) | ||

| Location of target joint | Upper | 16 (21.92) | 5 (8.33) | 11 (15.49) | 0.444 |

| Lower | 55 (41.98) | 27 (45.00) | 28 (39.44) | ||

| All | 60 (45.80) | 28 (46.67) | 32 (45.07) | ||

| Inhibitory antibody | No | 133 (88.67) | 64 (87.67) | 69 (89.61) | 0.708 |

| Yes | 17 (11.33) | 9 (12.33) | 8 (10.39) | ||

| Hepatitis (B or C) | Yes | 30 (20.00) | 11 (15.07) | 19 (24.68) | 0.142 |

| No | 120 (80.00) | 62 (84.93) | 58 (75.32) | ||

| Family history | Yes | 66 (44.00) | 33 (45.21) | 33 (42.85) | 0.032 |

| No | 54 (36.00) | 20 (27.40) | 34 (44.16) | ||

| Unknown | 30 (20.00) | 20 (27.40) | 10 (12.99) | ||

| Body mass index (kg/m2) |

Underweight | 18 (12.00) | 7 (9.59) | 11 (14.29) | 0.666 |

| Normal | 69 (46.00) | 35 (47.95) | 34 (44.16) | ||

| Overweight or obese | 63 (42.00) | 31 (42.46) | 32 (41.55) | ||

| Treatment strategy | On-demand | 129 (86.00) | 63 (86.30) | 66 (85.71) | 0.918 |

| Prophylaxis | 21 (14.00) | 10 (13.70) | 11 (14.29) | ||

| Type of products used | Blood-derived products | 118 (78.67) | 60 (82.19) | 58 (75.32) | 0.305 |

| Recombinant products | 32 (21.33) | 13 (17.81) | 19 (24.67) | ||

| Knowledge | |||||

| Knowledge score (0–4) | Less than full mark (<4) | 117 (78.00) | 61 (83.56) | 56 (72.73) | 0.109 |

| Full mark (=4) | 33 (22.00) | 12 (16.44) | 21 (27.27) | ||

| Economic condition | |||||

| Borrowing money | Yes | 104 (69.33) | 46 (63.01) | 58 (75.32) | 0.102 |

| No | 46 (30.67) | 27 (36.99) | 19 (24.68) | ||

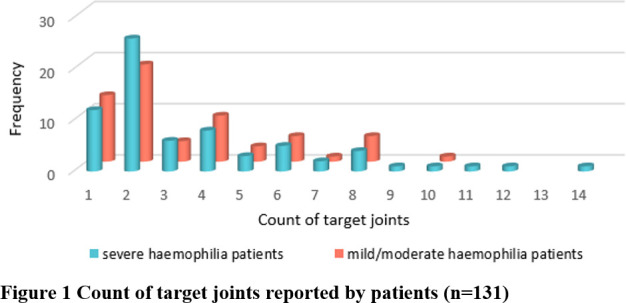

In total, 131 (87.33%) patients reported 462 target joints. More target joints were reported in the patients with severe haemophilia (3.39±2.96) compared with those with mild/moderate haemophilia (2.75±2.47). Only the severe patients reported more than 10 target joints (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Count of target joints reported by patients (n=131).

Haemophilia-related knowledge

Most (78%) respondents did not achieve a full mark for the haemophilia-related knowledge (table 1). More than 73% of respondents obtained their knowledge from fellow patients, compared with 57% from medical workers (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Source of knowledge.

Health-related quality of life

The vast majority of respondents reported problems in relation to the five dimensions of the EQ-5D-5L (table 2). About 40% reported no problem in SC, 26% in AD, 15% in MO, 14% in UA and 2% in PD. Only one respondent reported no problem at all across all of the five dimensions. This translated into a mean EQ-5Dutility index score of 0.51 (SD=0.34). On average, the respondents gave a VAS rating of 48.05 (SD=26.15). The patients with severe haemophilia experienced more problems (table 2) and rated lower in VAS (46.96±27.14 vs 49.21±25.20, p=0.017) than those with mild/moderate haemophilia, despite a lack of difference in the EQ-5Dutility index (0.46±0.37 vs 0.56±0.30, p=0.737).

Table 2.

Frequency of problems and EQ-5Dutility index and VAS scores in study participants (n=150)

| Dimension | Participants, n (%) | ||||

| All | Mild/moderate patients | Severe patients | |||

| Mobility | No problem | 22 (14.67) | 12 (16.44) | 10 (12.98) | 0.349 |

| Slight problem | 64 (42.67) | 35 (47.95) | 29 (37.66) | ||

| Moderate problem | 34 (22.67) | 15 (20.55) | 19 (24.68) | ||

| Severe problem | 15 (10.00) | 7 (9.59) | 8 (10.39) | ||

| Unable | 15 (10.00) | 4 (5.48) | 11 (14.29) | ||

| Self‐care | No problem | 61 (40.66) | 37 (50.68) | 24 (31.17) | 0.035 |

| Slight problem | 51 (34.00) | 23 (31.51) | 28 (36.36) | ||

| Moderate problem | 19 (12.67) | 8 (10.96) | 11 (14.29) | ||

| Severe problem | 13 (8.67) | 5 (6.85) | 8 (10.39) | ||

| Unable | 6 (4.00) | 0 (0.00) | 6 (7.79) | ||

| Usual activities | No problem | 21 (14.00) | 13 (17.81) | 8 (10.39) | 0.196 |

| Slight problem | 62 (41.33) | 31 (42.47) | 31 (40.26) | ||

| Moderate problem | 29 (19.33) | 12 (16.44) | 17 (22.08) | ||

| Severe problem | 18 (12.00) | 11 (15.06) | 7 (9.10) | ||

| Unable | 20 (13.33) | 6 (8.22) | 14 (18.18) | ||

| Pain/discomfort | No problem | 3 (2.00) | 1 (1.37) | 2 (2.60) | 0.397 |

| Slight problem | 58 (38.67) | 34 (46.58) | 24 (31.17) | ||

| Moderate problem | 49 (32.67) | 22 (30.14) | 27 (35.06) | ||

| Severe problem | 20 (13.33) | 8 (10.96) | 12 (15.58) | ||

| Extreme problem | 20 (13.33) | 8 (10.99) | 12 (15.58) | ||

| Anxiety/depression | No problem | 39 (26.00) | 20 (27.40) | 19 (24.68) | 0.813 |

| Slight problem | 58 (38.67) | 30 (41.10) | 28 (36.36) | ||

| Moderate problem | 30 (20.00) | 13 (17.81) | 17 (22.08) | ||

| Severe problem | 19 (12.67) | 9 (12.33) | 10 (12.99) | ||

| Extreme problem | 4 (2.67) | 1 (1.37) | 3 (3.90) | ||

| EQ-5Dutility index | Mean±SD | 0.51±0.34 | 0.56±0.30 | 0.46±0.37 | |

| Median (range) | 0.61 (–0.39 to 1.0) | 0.65 (–0.21 to 1.0) | 0.55 (–0.39 to 1.0) | ||

| EQ-5D VAS score | Mean±SD | 48.05±26.15 | 49.21±25.20 | 46.96±27.14 | |

| Median (range) | 47.50 (0–100) | 50.00 (0–100) | 44.00 (0–100) | ||

VAS, Visual Analogue Scale.

The patients who reported no target joint had higher HRQoL as measured by the EQ-5Dutility index regardless of the location of the target joints (figure 3).

Figure 3.

EQ-5Dutility index scores of patients by location of target joints.

Factors associated with HRQoL

The respondents who were older (≥25), reported more target joints (≥2), were unemployed, achieved a low knowledge score (<4) and borrowed money had lower EQ-5Dutility scores after adjustment for variations in other variables. However, only the count of target joints was found to be a significant predictor of the VAS scores (table 3).

Table 3.

Factors associated with the EQ-5Dutility index and VAS scores: results of multivariate regression models (n=150)

| Variables | EQ-5Dutility index | EQ-5D VAS score | ||||||

| β | 95% CI | P value | Tolerance VIF | β | 95% CI | P value | Tolerance VIF | |

| Constant | 1.224 | −0.591 to 3.038 | 0.185 | 0.256 | −1.641 to 2.154 | 0.790 | ||

| Age (vs <25 years) | −0.157 | −0.282 to −0.032 | 0.014 | 0.806 1.241 | −0.128 | −0.259 to 0.003 | 0.055 | 0.806 1.241 |

| Urban residency (vs urban) | −0.127 | −0.468 to 0.213 | 0.460 | 0.825 1.212 | −0.197 | −0.553 to 0.159 | 0.275 | 0.825 1.212 |

| Married (vs unmarried) | 0.084 | −0.246 to 0.414 | 0.616 | 0.783 1.276 | 0.035 | −0.311 to 0.380 | 0.843 | 0.783 1.276 |

| Inhibitory antibody (vs no) | 0.003 | −0.470 to 0.475 | 0.991 | 0.873 1.146 | −0.137 | −0.631 to 0.357 | 0.584 | 0.873 1.146 |

| Severe (vs mild/moderate) | −0.198 | −0.497 to 0.101 | 0.193 | 0.876 1.131 | −0.033 | −0.345 to 0.280 | 0.837 | 0.876 1.142 |

| Two or more target joints (vs <2) | −0.422 | −0.642 to −0.202 | <0.001 | 0.885 1.131 | −0.340 | −0.571 to 0.110 | 0.004 | 0.885 1.131 |

| Prophylaxis (vs on-demand) | 0.053 | −0.384 to 0.491 | 0.809 | 0.848 1.179 | 0.297 | −0.160 to 0.755 | 0.201 | 0.848 1.179 |

| Not working (vs employed) | −0.373 | −0.714 to −0.031 | 0.033 | 0.929 1.077 | −0.101 | −0.458 to 0.256 | 0.576 | 0.929 1.077 |

| Hepatitis (vs no) | 0.211 | −0.169 to 0.590 | 0.274 | 0.849 1.178 | 0.328 | −0.069 to 0.725 | 0.104 | 0.849 1.178 |

| High knowledge (vs low) | 0.398 | 0.039 to 0.758 | 0.030 | 0.880 1.136 | 0.342 | −0.035 to 0.718 | 0.075 | 0.880 1.136 |

| Not borrowing money (vs yes) | 0.420 | 0.085 to 0.754 | 0.014 | 0.821 1.218 | 0.271 | −0.079 to 0.621 | 0.128 | 0.821 1.218 |

| R2 | 0.290 | 0.197 | ||||||

| R2adj | 0.233 | 0.133 | ||||||

VAS, Visual Analogue Scale.

Poor administration of coagulation medicines and the negative impacts of haemophilia on work and personal relationships were described by the respondents as major contributors to lowered quality of life (table 4).

Table 4.

Major themes extracted from the answers to the open-ended question

| Theme | Subtheme examples of quotes | ||

| Poor administration of coagulation medicines | Low availability of coagulation medicines | 1 | ‘There are no needed medicines in the primary hospital’. |

| 2 | ‘There is a lack of medicines’. | ||

| 3 | ‘The primary hospital should take responsibility to supply the medicines’. | ||

| 4 | ‘It is difficult to buy needed medicines’. | ||

| 5 | ‘‘This disease does not need hospital treatment; but medicines are expensive and difficult to buy. This problem needs to be addressed as this disease damages multiple organs and long-term use of medicines is required’. | ||

| 6 | ‘I am from the countryside and I can only obtain the medicines from the big city’. | ||

| 7 | ‘I think supply of medications is the most important thing to be solved’. | ||

| Irregular use of medications | 8 | ‘To ensure the timely use of drugs to prevent haemophilia, reduce the rate of disability, improve the quality of life’. | |

| Adverse impacts of haemophilia on work and life | Low work ability | 9 | ‘We can’t work and need a better healthcare system’. ‘We have lost the ability to work and have no source of income’. |

| 10 | |||

| 11 | ‘I am incapable of working’. | ||

| Incomplete family life | 12 | ‘We lost the ability to survive, work and get married’. | |

Discussion

In recent years, the HRQoL of patients with haemophilia has attracted increasing attention from the research community.8 34 The EQ-5D is perhaps the most widely used instrument for assessing HRQoL in patients with various disease conditions.12 This study assessed the HRQoL of 150 patients in Heilongjiang of China using the EQ-5D-5L. The results indicate that patients with haemophilia have an average utility score of 0.5 and an average VAS score of 48, lower than those with other chronic conditions in China.35 The patients with haemophilia in Heilongjiang also have lower EQ-5Dutility scores in comparison with those reported in other settings (0.51 vs 0.77), although the EQ-5D population norms in China are equal to or even higher than those of other settings.36

The multivariate linear regression models show that older age (>25 years), two or more target joints, not working, low levels of knowledge of the disease and borrowing money to pay for medical treatments are independent predictors of lower EQ-5Dutility scores after adjustment for variations in other variables. Although severity of haemophilia did not appear as a predictor of HRQoL, we cannot exclude the possibility of the association between severity and HRQoL. This is because the patients with severe haemophilia reported more target joints than the patients with mild/moderate haemophilia.37 It is worth noting that the regression models identified more predictors for the EQ-5Dutility index scores than those for the VAS scores. This may be a result of the differences in the conceptualisation of the two measurements. The EQ-5D VAS measures the overall health of patients, which may be determined by some factors beyond the five dimensions. By contrast, the EQ-5Dutility index is a score derived from the public preference to the experiences of the five dimensions of problems. Interestingly, the EQ-5Dutility index appears to be more sensitive to the characteristics of patients with haemophilia compared with the EQ-5D VAS. Previous studies have shown similar results.17

Working and employment are associated with higher HRQoL of patients with haemophilia according to this study. We found that 84.67% of the patients were not working (either on sick leave or unemployed). The impacts of the disease on work and employment are a serious concern of the patients according to the data captured by the open-ended question. We found that more than 87% of the patients did not take regular prophylaxis treatment. Previous research showed that an absence of prophylaxis treatment can result in increased target joints, reducing the work ability and employment opportunities of the patients due to joint dysfunction and chronic pain.38 There is empirical evidence supporting the association between unemployment and low HRQoL.39 A job provides people with a sense of identity, which can help people to maintain self-esteem and good interpersonal relationships.17

The low level of knowledge of the patients with haemophilia on their disease conditions is concerning. Only a small percentage (22%) of the participants achieved a full mark. The low level of knowledge is an independent predictor of low HRQoL after controlling for variations in other variables.

We found more than 73% of the patients acquired relevant knowledge from their fellow patients, compared with 57% from medical workers and 48% from patient consultations. Although this is a positive indication of self-support from patients,40 the lack of effective communications between patients and medical workers may increase the risk of misinformation. It appears that patients are likely to prefer to obtain knowledge through modern information technologies rather than traditional lectures. About 62% reported acquisition of knowledge from the internet, compared with 28% from public lectures.

Consistent with findings of other studies, this study identified financial barriers as an independent predictor of HRQoL. About 69% of the participants borrowed money for the treatment of haemophilia, which is significantly associated with lower HRQoL. The treatment costs for haemophilia are expensive.41 Some patients with haemophilia are unable to afford the high costs. The loss of job opportunities can further exacerbate the affordability problem. In the past decade, the Chinese government has attempted to revitalise primary care, offering affordable essential medical care for people, in particular, those with low income. However, our study participants reported difficulties to obtain needed medicines from the primary care facilities. This may exert additional financial burdens on the patients as they have to travel to large hospitals to purchase medicines which are often more expensive.

Limitation

There are some limitations in this study. Data were collected through patient reports, which may influence the accuracy of some data such as the severity of the disease and the inhibitor status. Selection bias of the study sample is likely to occur as this study adopted a snowball sampling strategy. The online survey might have excluded the patients who did not have good access to the internet.

Conclusion

Low HRQoL of patients with haemophilia is evident in China as measured by the ED-5D-5L. Older age (>25 years), two or more target joints, not working, low levels of knowledge of the disease and borrowing money to pay for medical treatments are associated with the low EQ-5Dutility scores.

The findings of this study have some policy implications. Social support needs to be strengthened in China for patients living with haemophilia. Universal access to prophylaxis is critical to prevent and control bleeding and to improve the HRQoL of patients with haemophilia. Although China has basically achieved universal coverage of health insurance,42 the scope and depth of the entitlements of the insured need to be expanded. It is equally, if not more, important to enhance the service capacity of primary care institutions. In addition to medical treatments, health workers should pay increasing attention to patient communications and patient education. This can be done through taking advantage of modern information technologies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dong, the president of Heilongjiang Blood Friends Home, for his suggestions on the questionnaire development, mobilisation of the survey participants and help in questionnaire distribution.

Footnotes

JN, LN and QZ contributed equally.

Contributors: YH and YC took overall responsibility for the study design, coordination of the survey, development of the analysis framework and writing of the manuscript. JN, LN and QZ participated in the design of the research, conducted the survey and data analyses, and drafted the manuscript. ZL, YM and XX participated in the design of the research, revised the manuscript and encoded qualitative data. QW and CL supervised the data analyses, interpreted the results and revised the manuscript. JN, LN and QZ contributed equally. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. YH acting as guarantor.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available because the datasets are currently used for another project but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study involves human participants and was approved by the ethics committee of Harbin Medical University (IRB HMUIRB20190601). Confidentiality of the data has been maintained throughout the study. The questionnaire started with an introduction of the purpose and procedure of the survey. Submission of the questionnaire was deemed informed consent. Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1.Mannucci PM, Tuddenham EG. The hemophilias--from royal genes to gene therapy. N Engl J Med 2001;344:1773–9. 10.1056/NEJM200106073442307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Srivastava A, Brewer AK, Mauser-Bunschoten EP, et al. Guidelines for the management of hemophilia. Haemophilia 2013;19:e1–47. 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2012.02909.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.White GC, Rosendaal F, Aledort LM, et al. Definitions in hemophilia. recommendation of the scientific Subcommittee on factor VIII and factor IX of the scientific and standardization Committee of the International Society on thrombosis and haemostasis. Thromb Haemost 2001;85:560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rodriguez-Merchan EC. Prevention of the musculoskeletal complications of hemophilia. Adv Prev Med 2012;2012:1–7. 10.1155/2012/201271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soucie JM, Grosse SD, Siddiqi A-E-A, et al. The effects of joint disease, inhibitors and other complications on health-related quality of life among males with severe haemophilia A in the United States. Haemophilia 2017;23:e287–93. 10.1111/hae.13275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.von Mackensen S, Gringeri A, Siboni SM, et al. Health-Related quality of life and psychological well-being in elderly patients with haemophilia. Haemophilia 2012;18:345–52. 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2011.02643.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carvalhosa AM, Henrard S, Lambert C, et al. Physical and mental quality of life in adult patients with haemophilia in Belgium: the impact of financial issues. Haemophilia 2014;20:479–85. 10.1111/hae.12341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O'Hara J, Walsh S, Camp C, et al. The impact of severe haemophilia and the presence of target joints on health-related quality-of-life. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2018;16:84. 10.1186/s12955-018-0908-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Isfordink CJ, Gouw SC, van Balen EC, et al. Hepatitis C virus in hemophilia: health-related quality of life after successful treatment in the sixth hemophilia in the Netherlands study. Res Pract Thromb Haemost 2021;5:e12616. 10.1002/rth2.12616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Poon J-L, Doctor JN, Nichol MB. Longitudinal changes in health-related quality of life for chronic diseases: an example in hemophilia a. J Gen Intern Med 2014;29 Suppl 3:760–6. 10.1007/s11606-014-2893-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qu Y, Nie X, Yang Z, et al. The prevalence of hemophilia in mainland China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 2014;45:455–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liang Z, Zhang T, Lin T, et al. Health-Related quality of life among rural men and women with hypertension: assessment by the EQ-5D-5L in Jiangsu, China. Qual Life Res 2019;28:2069–80. 10.1007/s11136-019-02139-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aledort L, Bullinger M, von Mackensen S, et al. Why should we care about quality of life in persons with haemophilia? Haemophilia 2012;18:e154–7. 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2012.02771.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Efficace F, Bottomley A, Smit EF, et al. Is a patient's self-reported health-related quality of life a prognostic factor for survival in non-small-cell lung cancer patients? A multivariate analysis of prognostic factors of EORTC study 08975. Ann Oncol 2006;17:1698–704. 10.1093/annonc/mdl183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Franchini M, Tagliaferri A, PMJCIiA M. The management of hemophilia in elderly patients. Clin Interv Aging 2007;2:361–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Poon M-C, Luke K-H. Haemophilia care in China: achievements of a decade of World Federation of hemophilia treatment centre twinning activities. Haemophilia 2008;14:879–88. 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2008.01821.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun J, Zhao Y, Yang R, et al. The demographics, treatment characteristics and quality of life of adult people with haemophilia in China - results from the HERO study. Haemophilia 2017;23:89–97. 10.1111/hae.13071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Statistics HBO, 2020. Available: http://www.hlj.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/tjgb/shgb/202004/t20200413_77332.html

- 19.Overview. Available: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/mic/overview

- 20.Carroll L, Benson G, Lambert J, et al. Real-World utilities and health-related quality-of-life data in hemophilia patients in France and the United Kingdom. Patient Prefer Adherence 2019;13:941–57. 10.2147/PPA.S202773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krieger N, Gruskin S. Frameworks matter: Ecosocial and health and human rights perspectives on disparities in women’s health: The case of tuberculosis. Journal of the American Medical Women’s Association 2001;56:137–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith AE, Sim J, Scharf T, et al. Determinants of quality of life amongst older people in deprived neighbourhoods. Ageing Soc 2004;24:793–814. 10.1017/S0144686X04002569 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hernanz V. OECD social, employment and migration working papers, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peng H. Research on dualistic Structure of the Urban and Rural areas and the Issue of Social Fairness in China [D. Sichuan University, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dimichele DM, Lacroix-Desmazes S, Peyvandi F. Subcommittee on factor VIII fix, et al. design of clinical trials for new products in hemophilia: communication from the SSC of the ISTH. J Thromb Haemost 2015;13:876–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davari M, Gharibnaseri Z, Ravanbod R, et al. Health status and quality of life in patients with severe hemophilia A: a cross-sectional survey. Hematol Rep 2019;11:7894. 10.4081/hr.2019.7894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shan M-J, Zou Y-F, Guo P, et al. Systematic estimation of BMI: a novel insight into predicting overweight/obesity in undergraduates. Medicine 2019;98:e15810. 10.1097/MD.0000000000015810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xie F, Pullenayegum E, Gaebel K, et al. A time Trade-off-derived value set of the EQ-5D-5L for Canada. Med Care 2016;54:98–105. 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wong ELY, Xu RH, Cheung AWL. Health-Related quality of life among patients with hypertension: population-based survey using EQ-5D-5L in Hong Kong SAR, China. BMJ Open 2019;9:e032544. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-032544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hernandez Alava M, Wailoo A, Grimm S, et al. EQ-5D-5L versus EQ-5D-3L: the impact on cost effectiveness in the United Kingdom. Value Health 2018;21:49–56. 10.1016/j.jval.2017.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li L, Liu C, Cai X, et al. Validity and reliability of the EQ-5D-5 L in family caregivers of leukemia patients. BMC Cancer 2019;19:522. 10.1186/s12885-019-5721-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luo N, Liu G, Li M, et al. Estimating an EQ-5D-5L value set for China. Value Health 2017;20:662–9. 10.1016/j.jval.2016.11.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Soloman SR, Sawilowsky SS. Impact of rank-based normalizing transformations on the accuracy of test scores. Journal of Modern Applied Statistical Methods 2009;8:448–62. 10.22237/jmasm/1257034080 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang H, Huang J, Kong X, et al. Health-Related quality of life in children with haemophilia in China: a 4-year follow-up prospective cohort study. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2019;17:28. 10.1186/s12955-019-1083-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu RH, Cheung AWL, Wong EL-Y. Examining the health-related quality of life using EQ-5D-5L in patients with four kinds of chronic diseases from specialist outpatient clinics in Hong Kong SAR, China. Patient Prefer Adherence 2017;11:1565–72. 10.2147/PPA.S143944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gautier L, Azzi J, Saba G, et al. PNS70 EQ-5D-5L in China and Japan: population norms and comparison between the countries. Value Health Reg Issues 2020;22:S94. 10.1016/j.vhri.2020.07.489 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Klamroth R, Pollmann H, Hermans C, et al. The relative burden of haemophilia A and the impact of target joint development on health-related quality of life: results from the ADVATE Post-Authorization safety surveillance (pass) study. Haemophilia 2011;17:412–21. 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2010.02435.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Manco-Johnson MJ, Soucie JM, Gill JC, et al. Prophylaxis usage, bleeding rates, and joint outcomes of hemophilia, 1999 to 2010: a surveillance project. Blood 2017;129:2368–74. 10.1182/blood-2016-02-683169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wiley RE, Khoury CP, Snihur AWK, et al. From the voices of people with haemophilia A and their caregivers: challenges with current treatment, their impact on quality of life and desired improvements in future therapies. Haemophilia 2019;25:433–40. 10.1111/hae.13754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tajfel H, Billig MG, Bundy RP, et al. Social categorization and intergroup behaviour. Eur J Soc Psychol 1971;1:149–78. 10.1002/ejsp.2420010202 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Colvin BT, Astermark J, Fischer K, et al. European principles of haemophilia care. Haemophilia 2008;14:361–74. 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2007.01625.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shan L, Wu Q, Liu C, et al. Perceived challenges to achieving universal health coverage: a cross-sectional survey of social health insurance managers/administrators in China. BMJ Open 2017;7:e014425. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-056668supp001.pdf (459.2KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available because the datasets are currently used for another project but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.