1. Introduction

During the last decade in Colombia, cancer incidence has significantly increased but cancer mortality has decreased, resulting in an increasing number of cancer survivors (Bray et al., 2018; Ferlay et al., 2015). This trend is expected to continue: it is estimated that by 2040, the incidence of cancer in Colombia will increase by 86.5%, higher than the global cancer incidence estimated for that year (63.4%) (Ferlay et al., 2015; International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2018) In 2012, the Colombian Ministry of Health issued the Plan Decenal para el Control del Cáncer en Colombia 2010–2021, the “Ten-Year Plan for Cancer Control in Colombia, 2012–2021,” which identified the need to rigorously track the care of cancer survivors in Colombia and called for further research (Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social de Colombia, 2012). In Colombia, health policy and healthcare must be developed to address cancer survivors’ needs.

In the United States (U.S.), also with a growing cancer survivor cohort, the National Research Council and the Institute of Medicine have published recommendations for changes in policy and healthcare to meet the needs of cancer survivors (Hewitt et al., 2006). The Office of Cancer Survivorship defines a “cancer survivor” as a person from the moment of diagnosis of cancer until death (Hewitt et al., 2006). The Colombian National Cáncer Institute (Instituto Nacional de Cancerología, 2017) defines survivorship as “the percentage of cancer patients who are alive after a determined number of years” (p. 28, English translation).We focus on cancer survivors in Colombia who have completed primary cancer treatment. According to Demiris et al. (2019), narrative reviews intend to “find an overall background or context for a specific problem or issue” (p. 30). The aim of this narrative review is to provide an overview of the social structure, healthcare system, and healthcare delivery in Colombia in relation to cancer survivorship. We then discuss the U.S. model of care for cancer survivors and offer recommendations that could be used for improving cancer survivors’ care in Colombia, highlighting the potential of nursing in meeting cancer survivors’ needs, and inform health policy. We reviewed the websites of the Colombian Minister of Health, the Colombia’s National Institute of Cancer, and the International Agency for Research on Cancer to inform this review.

2. Colombian social structure

Colombia is an upper-middle income country, with significant ethnic, religious, and socioeconomic diversity (de Vries et al., 2016). Internal armed conflict and economic changes in Colombia since the 1960s have resulted in massive internal migration (Ministerio de Cultura, 2006), so that most of the Colombian population now resides in urban areas. The Colombian National Administrative Department of Statistics (Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística, n.d.) stratifies Colombian citizens into six socioeconomic levels, based on external and internal characteristics of their residence provided in the national census (e.g., how many rooms, bathrooms, televisions, and computers in the house; access to electricity, water, and sewer; etc.). People with fewer economic resources and amenities are in stratum 1, while people with greater economic resources are in stratum 6. The Colombian government established this system in order to determine the allocation and distribution of resources, public services, and subsidies to Colombian citizens.

3. Healthcare system in Colombia

The Colombian constitution defines Colombia as a social state governed by the rule of law—a state “founded on respect for human dignity, on the work and solidarity of its people” (English translation) (República de Colombia, 1991). In 1993, the government created the Sistema General de Seguridad Social en Salud, the General System of Social Security in Health, to provide healthcare coverage for the nation’s population (República de Colombia, 1993). This law classifies citizens into three regimes for health care coverage. Two of the regimes are based on economic ability—the contributory regime, for those who can afford health insurance, and the subsidized regime, for those who cannot. A third regime, the special regime, was established for military personnel, police, teachers, and workers in public educational institutions.

“Health-promoting entities” (entidades promotoras de salud,) are independent enterprises in charge of collecting and managing health care fees in Colombia, and “health provider institutions” (instituciones prestadoras de servicios de salud) are separately responsible for providing Colombian health care services.

Because Colombia’s health-promoting entities are responsible for collecting and managing funds for healthcare, whereas health provider institutions are responsible for providing healthcare services, each health-promoting entity contracts with health provider institutions so that people can receive paid healthcare services. However, the coverage plans and services that people can access depend on their healthcare regime (contributory, subsidized, specialized) and on whether the health provider institutions is public, private, or mixed. Public institutions must provide care regardless of a person’s healthcare regime, and the services that they offer vary, categorized as level 1, 2, or 3 (República de Colombia, 1990). Whereas private institutions are not required to provide healthcare to a person whose health-promoting entity does not have a contract with them, except in cases of emergency.

According to the Colombian Ministry of Health, 90% of health provider institutions are private, 9.8% public, and 0.18% mixed (Rozo & Acosta, 2016). Almost all institutions are located in urban areas, so healthcare services for people in rural areas are very limited (see Supplementary Figures 1 – 3). Most institutions in rural communities or rural areas with dispersed settlements are public, categorized as level 1 (Rozo & Acosta, 2016), meaning that they serve as emergency or first aid clinics and are less equipped to handle diagnosis, treatment, and management of acute and chronic diseases.

4. Healthcare delivery in Colombia in relation to cancer

4.1. Cancer “control”

The Colombia’s National Institute of Cancer, founded by the Colombian Ministry of Health in 1934, aims to provide “comprehensive cancer control through health care services to patients, research, health care team training and development of public health actions” (República de Colombia, 2009). It also advises the Colombian Ministry of Health on oncology-related issues, serves as a site for cancer research and teaching (República de Colombia, 2009) and is the entity in charge of Colombian cancer registries (República de Colombia, 2010).

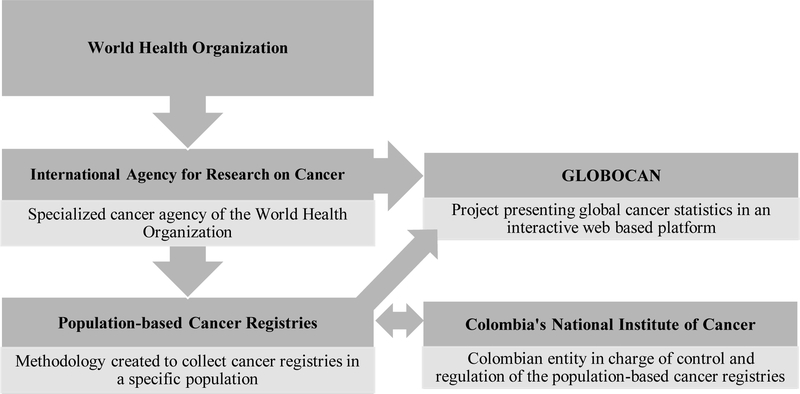

Despite being an upper-middle income country, Colombia lacks adequate funding to accurately measure and comprehensively monitor cancer incidence and mortality at the national level (Pardo & Cendales, 2018). However, the World Health Organization’s International Agency for Research on Cancer has supported Colombia’s development of population-based cancer registries to capture data for cancer incidence and mortality (de Vries et al., 2016; International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2020; Pardo & Cendales, 2018; Wiesner, 2018) (See Figure 1)

Figure 1. Relationships between the International Agency for Research on Cancer, GLOBOCAN, Population-Based Cancer Registries and Colombia’s National Institute of Cancer.

Note: Data are from (Bray et al., 2018; Gil et al., 2019; International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2020)

The Colombia’s National Institute of Cancer pioneered the use of a population-based cancer registry in the city of Cali, the first to employ a registry to track cancer statistics in South America. This cancer registry has been in use since 1962 (de Vries et al., 2016). Subsequently they created four additional municipal cancer registries to provide representative estimates of cancer incidence and mortality, in Pasto, Manizales, Bucaramanga, and Barranquilla. However, all five cancer registries together represent only about 12% of the total Colombian population (de Vries et al., 2016; Pardo & Cendales, 2018).

The cancer registries in Colombia, along with mortality rates provided by Colombia’s National Administrative Department of Statistics, provide data about cancer patterns and trends as they evolve (Bray et al., 2014; Pardo & Cendales, 2018; Wiesner, 2018). The cancer registries report data to the Colombia’s National Institute of Cancer and to the International Agency for Research on Cancer’s GLOBOCAN, which publishes cancer statistics for 185 countries, including Colombia (Bray et al., 2018; de Vries et al., 2016; Gil et al., 2019). However, the data collected by in Barranquilla’s cancer registry do not meet GLOBOCAN quality standards, so that GLOBOCAN’s statistics for Colombia reflect only 9% of the Colombian population (C. Allemani et al., 2018).

From 2012 to 2018, cancer incidence in Colombia increased, differing between men and women. In 2018, breast cancer was the most common cancer for women both in Colombia and worldwide. However, the breast cancer age-standardized incidence rate was lower in Colombia (44.1) than worldwide (46.3) (Bray et al., 2018). For men in Colombia, the leading age-standardized incidence cancer rate was prostate cancer (49.8), with incidence significantly higher than worldwide (ASIR 29.3) (Bray et al., 2018). Table 1 provides incidence rates for specific cancers in Colombia.

Table 1.

Age-standardized incidence rates per 100,000 people in Colombia for specific cancer types, 2018

| Women | Men | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer | Incidence Rates | Cancer | Incidence Rates |

| Breast | 44.1 | Prostate | 49.8 |

| Colorectal | 15.0 | Stomach | 17.6 |

| Thyroid | 14.5 | Colorectal | 16.9 |

| Cervical | 12.7 | Lung | 12.7 |

| Stomach | 8.9 | Nonmelanoma skin cancer | 9.6 |

Data are from (Bray et al., 2018).

4.2. Cancer survival rates

Allemani et al. (Claudia Allemani et al., 2015) have reported cancer survival rates between 1995 and 2009 in 67 countries including Colombia. Cancer survival data for Colombia were provided by the cancer registries during three time periods: 1995–1999, 2000–2004, 2005–2009. The 5-year survival rates for colorectal, prostate, and breast cancer in Colombia increased over time. However, those improvements were not as large as in developed countries (Claudia Allemani et al., 2015; Arias-Ortiz & de Vries, 2018). Arias-Ortiz and de Vries (Arias-Ortiz & de Vries, 2018) have analyzed survival rates of people with breast, cervix, lung, prostate, and stomach cancer diagnosed from 2003 to 2007 in the city of Manizales in Colombia. Prostate, breast, and cervical cancer survival percentages were the lowest, and stomach and lung cancer survival percentages were the highest in Manizales’ cancer registry (see Supplementary Table 1 for 5-year survival percentages in Manizales’ cancer registry vs. the grouped cancer registries). de Vries et al. (de Vries et al., 2015) have reported an even lower 5-year overall survival rate, 11%, for stomach cancer in Bucaramanga from 2003 to 2009.

The differences in data reported by Allemani et al. (Claudia Allemani et al., 2015), Arias-Ortiz and de Vries (Arias-Ortiz & de Vries, 2018), and de Vries et al. (de Vries et al., 2015) highlight disparities in cancer survival rates among Colombian cities that likely reflect those cities’ social, economic, and cultural characteristics. For example, survival rates differ depending on socioeconomic level (strata 1–6) and healthcare coverage regime (Arias-Ortiz & de Vries, 2018; de Vries et al., 2015; Pardo & de Vries, 2018). In de Vries et al. (de Vries et al., 2015), stomach cancer survival rates ranged from 7.4% to 20.7%, with higher rates for socioeconomic levels 5 and 6 and lower rates for levels 1 and 2. Similarly, survival rates ranged from 8.3% to 15.8%, with higher rates found for those in the special coverage regime and lower rates for those in the subsidized coverage regime (de Vries et al., 2015).

4.3. Social determinants of health

Social determinants of health help explain differences in health outcomes (Carmona-Meza & Parra-Padilla, 2015). One way to characterize the impact of social determinants of health on cancer-related outcomes in Colombia is to use the Gini coefficient, an inequality metric. The Gini coefficient of a region in the country can range from 0, representing complete equality among the region’s citizens in comparison with national averages, to 1, representing complete inequality among the region’s citizens in comparison with national averages (Departamento Nacional de Estadística, 2019). Regional Gini coefficients vary across Colombia from 0.446 in rural communities and dispersed rural settlements to 0.487 in urban areas (Departamento Nacional de Estadística, 2019).These values portray a redistribution of the population as people move from rural areas to cities, where inequalities increase. Inequalities are also higher in bigger cities such as Bogotá than in smaller cities (Departamento Nacional de Estadística, 2019).Another indicator of social and economic status consists of illiteracy rates. In rural areas, the illiteracy rate is reported as 12.6%, whereas in urban areas it is 5.24%, highlighting yet another geographical disparity (Ministerio de Educación, 2018). A third indicator is poverty, which is 1.5 times higher in rural communities and dispersed rural settlements than in urban areas (Departamento Nacional de Estadística, 2019). These factors and others highlight the many challenges to equality for Colombians.

4.4. Cancer care delivery

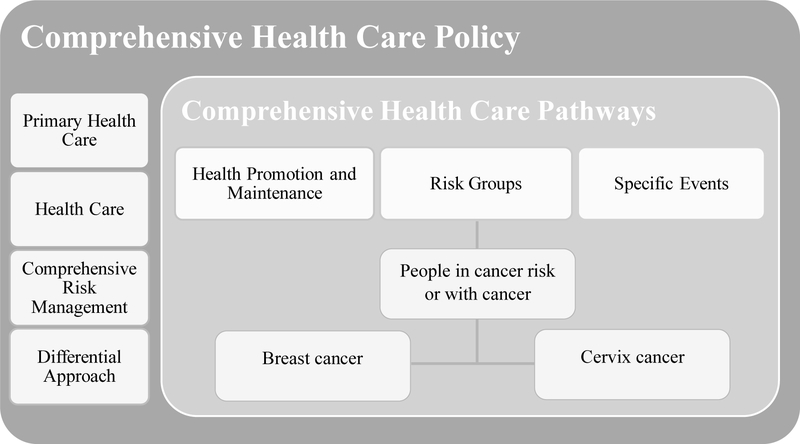

In 2016, the Colombian Government issued Resolution No. 429, the Comprehensive Health Care Policy (Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social de Colombia, 2016c) to guide the healthcare system in improving population health. This healthcare model includes primary healthcare (health promotion and disease prevention), healthcare delivery (self-care, family care, and community care throughout the life course), comprehensive risk management (early detection and management of disease), and different approaches to healthcare delivery, taking into account social determinants of health. Also in 2016, Resolution No. 3202 provided guidelines for the implementation of the Comprehensive Health Care Policy. The guidelines established comprehensive healthcare pathways (Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social de Colombia, 2016b, 2016a), in three categories: (1) health promotion and maintenance, (2) risk groups, and (3) specific events (see Figure 2 for a schematic representation of comprehensive health care policy and comprehensive healthcare pathways).

Figure 2. Comprehensive Health Care Policy and Comprehensive Health Care Pathways.

The health care pathways, created to implement the four main components of the comprehensive health care policy, comprise three pathways: health promotion and maintenance, specific events, and risk group. The latter includes a specific pathway for people with cancer risk or with cancer. To date, only breast and cervix cancer comprehensive health care pathway has been established (Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social de Colombia, 2016a, 2016d).

Cancer care falls within the risk groups healthcare pathway (Figure 2). Colombia embraces clinical practice guidelines for early detection, diagnosis, treatment, follow-up and rehabilitation of the five most common cancers (prostate, breast, colorectal, stomach, and cervical). The risk groups healthcare pathway also have specific guidelines for populations at risk for cancer or with cancer. These define members of the healthcare team and focus on health promotion to decrease cancer risk—on promoting cancer screening, treatment, and follow-up. For example, the comprehensive healthcare pathway for breast cancer defines more than 20 interventions targeting populations according to the life course, served by defined healthcare teams to implement each intervention. (Supplementary Table 2 presents the pathway for breast cancer.)

Depending on a person’s age and health history, a primary care physician will order cancer screening tests. If any abnormality is identified, they will be referred to a specialized medical doctor, depending on what the screening was for (e.g., to a gynecologist or a urologist) to undergo additional tests, including a pathological study for cancer confirmation, grading, and staging. When a cancer diagnosis is confirmed, an oncologist and the patient will determine the course of treatment (radiation therapy, chemotherapy, or surgery) and schedule follow-up appointments for overall health and symptom assessments, analyses of laboratory tests, and referrals to other specialists (e.g., mental health providers). Oncology nurses administer medications, conduct nursing assessments, make nursing diagnoses, administer treatments, and evaluate care throughout cancer treatment. At the end of antineoplastic treatment, the specialist and the oncologist schedule follow-up appointments according to the specific clinical practice guideline. These follow-ups focus mainly on identifying cancer relapse.

4.5. Cancer survivorship priorities in Colombia

The Ten-Year Plan for Cancer Control in Colombia 2012–2021 (Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social de Colombia, 2012) provides guidance to improve cancer control and care, outlining six strategic priorities (Table 2). Cancer survivorship needs are included in strategy 3 (health care, recovery, and coping with damage caused by cancer), strategy 4 (improving quality of life [QOL] of people with cancer and cancer survivors), and strategy 5 (knowledge and technology management for cancer control). Particular emphasis is placed on increasing survivorship in people under 18 with pediatric leukemia by 2021 (strategy 3), creating a policy for survivors returning to life work by 2017 (strategy 4), measuring QOL in people with cancer and cancer survivors (strategy 4), and conducting research to collect data and reporting survivorship rates for the five most incident cancers by 2015 (strategy 5) (Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social de Colombia, 2012).

Table 2.

Strategic Lines of the Ten-Year Plan for Cancer Control in Colombia, 2012–2021.

| 1 | Risk Control (Primary Prevention) |

| 2 | Early Detection of the Illness |

| 3 | Healthcare, Recovery, and Coping with Damage Caused by Cancer |

| 4 | Improvement of Quality of Life of Cancer Patients and Survivors |

| 5 | Knowledge and Technology Management for Cancer Control |

| 6 | Training and Development of Healthcare Team |

Data are from (Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social de Colombia, 2012)

Even though cancer survivorship issues are part of Colombia’s comprehensive healthcare pathways and the Ten-Year Plan for Cancer Control in Colombia 2012–2021, survivors still experience unmet needs owing to persistent, debilitating symptoms that can accompany antineoplastic therapies. However, no governmental or research reports have addressed survivors’ ongoing needs, presenting a critical gap in the literature. In addition, to date there are no policies for survivors’ returning to work or QOL measures for survivors after treatment ends. Because survival rates are increasing and cancer survivors have unique, ongoing health care needs after anticancer treatment is completed, it is essential to strengthen the provision of healthcare services for survivors in Colombia.

5. Cancer survivorship in the United States

In the U.S. at the end of the last century, comprehensive care for people diagnosed with cancer at all stages of disease including survivorship was acknowledged to be essential. The U.S. National Cancer Institute distinguishes three stages of cancer survival: (1) acute survival, starting with the diagnosis of cancer and focusing on anticancer therapy; (2) extended survival, beginning with cancer remission or when anticancer therapy finishes; and (3) permanent survival, when a person is considered “cured” of cancer, but still deals with secondary effects of cancer treatment (Hewitt et al., 2006).

5.1. From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition

In 2006, the U.S. National Academy of Sciences and Institute of Medicine (now the National Academy of Medicine) published the seminal report From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition, to raise awareness about cancer treatment, improve cancer survivors’ QOL, and provide policies to guarantee their rights (Hewitt et al., 2006). This report makes 10 recommendations based on the physical and psychological concerns of cancer survivors that include coordinated care, care planning, measurement and delivery of high-quality cancer survivorship care, educating providers about survivorship care, mitigating employment issues for survivors returning to work, expanding insurance coverage, and identifying research priorities for funding entities (Table 3). Fifteen years after these recommendations were published, U.S. progress in cancer survivorship care has been attributed to the collective recognition of survivorship as a distinct phase of cancer in textbooks, academic journals dedicated to survivorship, educational programs, frequent media coverage of survivors’ stories, and oncology providers who complete survivorship planning (Nekhlyudov et al., 2017).

Table 3.

From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition, Recommendations

| 1 | Work to raise awareness of the needs of cancer survivors, establish cancer survivorship as a distinct phase of cancer care, and act to ensure the delivery of appropriate survivorship care. |

| 2 | Provide comprehensive care summary and follow-up plan that are clearly and effectively explained. |

| 3 | Develop clinical practice guidelines, assessment tools, and screening instruments to help identify and manage late effects of cancer and its treatment. |

| 4 | Quality of survivorship care measures should be developed through public/private partnerships. |

| 5 | Support demonstration programs to test models of coordinated, interdisciplinary survivorship care in diverse communities and across systems of care. |

| 6 | Develop comprehensive cancer control plans that include consideration of survivorship care, and promote the implementation, evaluation, and refinement of existing state cancer control plans. |

| 7 | Provide educational opportunities that equip healthcare providers to address healthcare and quality of life issues facing cancer survivors. |

| 8 | Act to eliminate discrimination and minimize adverse effects of cancer on employment, while supporting cancer survivors with short- and long-term limitations in their ability to work. |

| 9 | Federal and state policy makers should act to ensure that all cancer survivors have access to adequate, affordable health insurance. |

| 10 | Increase support of survivorship research and expand mechanisms for its conduct. |

Data are from (Hewitt et al., 2006)

Guidelines for survivorship care have been disseminated by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 2020), the American Cancer Society (American Cancer Society, 2020), and the American Society of Clinical Oncology (American Society of Clinical Oncology, 2020). The latter is leading the development of quality indicators for survivorship care (Mayer et al., 2015). Funding opportunities from the National Cancer Institute, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services emphasize implementation science for cost-effective cancer survivorship care (Nekhlyudov et al., 2017). Healthcare access for survivors has been facilitated by broader health policies in the U.S., including the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act(Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act 42 U.S.C. § 18001, 2010). The economic impact of cancer care is still a growing area of research, and more policy work is needed to eliminate barriers for survivors as they try to maintain or return to work, in order to ensure optimal occupational outcomes (Nekhlyudov et al., 2017)

6. Recommendations for Colombian cancer survivorship care based on the U.S. health care system model

Cancer survivorship care in Colombia is in its infancy. Most resources are allotted to cancers with the highest incidence and to anti-cancer treatments. The Colombian Ministry of Health could utilize the recommendations and priorities for survivorship care put forth by the U.S. in 2006 as a model for developing a more comprehensive Colombian model of cancer survivorship care. First, we recommend that survivorship be recognized as a distinct part of the cancer trajectory, understanding that cancer care does not end when a person is deemed “cancer free” (see Table 3, recommendation 1). In the U.S., it is widely accepted that long-term effects of cancer and its treatment can extend for months or years after treatment is over (Nekhlyudov et al., 2017). Recognizing the survivorship phase of cancer care can help guide policies and prioritize healthcare services for survivors who need ongoing monitoring of cancer recurrence and secondary cancer occurrences, access to resources for health-promoting and wellness practices, and monitoring and management of ongoing late and long-term effects of treatment.

Second, we recommend that resources be directed to strengthen methods and metrics for tracking cancer survivorship, including quality measures, in order to accurately represent the Colombian population (Table 3, recommendation 4). Population-based cancer survival rates are considered proxies for access to healthcare services and timely and effective treatment (C. Allemani et al., 2018) Colombian cancer registries data are used to estimate cancer prevalence and survival and to assess cancer control plans (Navarro et al., 2013). However, because the quality and accuracy of data collected by the cancer registries are questionable, it is necessary to increase the number of cancer registries across the country to more accurately reflect the Colombian population and to ensure that they track data consistently and according to international quality standards. These measures would allow more precise monitoring of survivorship services and efficacy of cancer control plans in Colombia.

Survivors experience residual symptoms from cancer and its treatment (Shi et al., 2011), and symptom burden interferes with a person’s ability to function, negatively affecting QOL (Burkett & Cleeland, 2007; Mao et al., 2007; Shi et al., 2011). Assessing and monitoring cancer symptoms and QOL of cancer survivors must be a national priority (Table 3, recommendation 3) (Burkett & Cleeland, 2007; Shi et al., 2011). Published evidence-based guidelines could be used as models for survivorship care in Colombia (American Cancer Society, 2020; American Society of Clinical Oncology, 2020; National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 2020). These guidelines have four essential components: (1) prevention of recurrence, incidence of other cancers, and late effects; (2) surveillance of spread, recurrence, occurrence of other cancers, and late medical and psychosocial effects; (3) treating health issues caused by cancer and its treatment; and (4) coordination of healthcare teams to meet all cancer survivors’ needs (Grunfeld et al., 2011; Hewitt et al., 2006; Luctkar-flude et al., 2015; Runowicz et al., 2016).

These guidelines, along with instruments to measure QOL and specific symptoms in cancer survivors, must be validated to address the acute, late, and long-term effects of cancer treatment for Colombian cancer survivors. Clinical guidelines for cancer survivorship in Colombia must account for the social, economic, and cultural characteristics of the Colombian population. Although Colombian healthcare does have clinical practice guidelines for early detection, diagnosis, treatment, monitoring, and rehabilitation of certain cancer types (Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social de Colombia, 2016d), these guidelines do not adequately or specifically address survivors’ needs including the late or long-term effects of cancer and its treatment, and they do not consider social determinants of health.

Our final recommendation is that healthcare professionals must be educated about cancer survivors’ unique needs in order to improve providers’ knowledge and practical skills for the care of survivors and their families (Table 3, recommendation 7) (Nevidjon et al., 2010). Boards that oversee Colombian continuing education, graduate programs, and certification, which are responsible for approving and providing professional credentials (República de Colombia, 1996), could facilitate improved educational initiatives and training. Partnerships between professional organizations and universities that produce educational materials for healthcare professionals, such as George Washington University’s National Cancer Survivorship Resource Center in the U.S. (The GW Cancer Institute, n.d.), could faciliate dissemination of educational materials in Colombia.

7. The potential for nursing practice to address survivorship needs in Colombia

Nurses play a fundamental role in the care of people with cancer in Colombia. Training nurses in cancer prevention, early detection, treatment, and symptom management for cancer survivors could provide Colombians with higher quality and timely delivery of cancer treatment and survivorship services, positively affecting the QOL of cancer survivors and their families along with improving health outcomes. In general, expanding nursing’s scope of practice in Colombia could help meet many healthcare needs in the Colombian population. Currently, the scope of practice of nurses in Colombia is limited, similar to that of a Registered Nurse in the U.S. In Colombia, there are no Advanced Practice Nurses. In oncological settings in other countries such as the U.S., Advanced Practice Nurses provide individual patient care, including survivorship and symptom management (Nevidjon et al., 2010). Oncology Advanced Practice Nurses have demonstrated cost-effectiveness, patient satisfaction, and quality care outcomes in diverse care settings in countries where they practice (Nevidjon et al., 2010). The Colombian government and institutes of higher education should consider expanding nurses’ scope of practice to include options for graduate education and licensure for advanced practice.

The Colombian healthcare model and associated policies may present barriers to advanced nursing practice. To address survivors’ needs, other possibilities might include expanded continuing education and more rigorous certifications for nurses. In Colombia, although licensed nurses can become certified in oncology by through continuing education, the certification model could be improved to include additional criteria, such as a given number of hours working in oncology settings and the passing of exams that evaluate competencies, as in the U.S. (Oncology Nursing Certification Corporation, 2020). Continuing education could include content on cancer survivors’ unique needs and appropriate care.

8. Conclusion

People in Colombia are categorized according to their economic resources, and these socioeconomic strata translate to health insurance regimes. Although disparities impact cancer survival across the country negatively, in 2016 the government of Colombia implemented Policy and Comprehensive Health Care Pathways, including a special pathway for cancer, which includes health promotion, early detection, timely treatment, rehabilitation, and follow-up considering social determinants of health. However, recommendations for the care of cancer survivors are not specific, and the long-term and late effects of cancer and its treatment remain unmet.

Similar trends in cancer survivorship that have been identified over recent decades in developed countries including the U.S. have led to changes in healthcare policy and clinical practice to meet the needs of cancer survivors. On the basis of the recommendations in From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivors: Lost in Transition, we suggest the following priorities, adapted for the Colombian context. First, survivorship must be recognized as a distinct, ongoing stage of cancer. Second, survivorship tracking must be strengthened through standardization of data from cancer registries and use of international metrics to evaluate the quality of cancer control and survivorship. Third, clinical guidelines for QOL and specific symptoms of survivors must be developed and adapted, and valid instruments must be used to evaluate the effectiveness of these guidelines. Finally, healthcare professionals, especially nurses, must be trained to provide timely, high-quality care, in order to meet survivors’ needs and increase QOL. The number of cancer survivors will continue to grow in Colombia, and policies must be developed and implemented in order to meet their needs and improve their health outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

The authors would like to thank Dr. John Bellquist in the Cain Center for Nursing Research at the University of Texas at Austin for his editing assistance.

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Universidad Nacional de Colombia strengthening research program with young talent in response to health challenges of vulnerable population (2018–2020) Colciencias [grant number 377, 2019].

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflict of interest: The Authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Allemani C, Matsuda T, Di Carlo V, Harewood R, Matz M, Nikšić M, Bonaventure A, Valkov M, Johnson CJ, Estève J, Ogunbiyi OJ, Azevedo e Silva G, Chen W-Q, Eser S, Engholm G, Stiller CA, Monnereau A, Woods RR, Visser O, … CONCORD Working Group. (2018). Global surveillance of trends in cancer survival 2000–14 (CONCORD-3): analysis of individual records for 37 513 025 patients diagnosed with one of 18 cancers from 322 population-based registries in 71 countries. The Lancet, 391(10125), 1023–1075. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)33326-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allemani Claudia, Weir HK, Carreira H, Harewood R, Spika D, Wang X, Bannon F, Ahn JV, Johnson CJ, Soeberg MJ, You H, Matsuda T, Bielska-lasota M, Storm H, Tucker TC, & Coleman MP (2015). Global surveillance of cancer survival 1995 – 2009 : analysis of individual data for 25 676 887 patients from 279 population-based registries in 67 countries ( CONCORD-2 ). The Lancet, 385(9972), 977–1010. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62038-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Cancer Society. (2020). American Cancer Society Survivorship Care Guidelines. https://www.cancer.org/health-care-professionals/american-cancer-society-survivorship-guidelines.html

- American Society of Clinical Oncology. (2020). Guidelines on Survivorship Care. https://www.asco.org/practice-policy/cancer-care-initiatives/prevention-survivorship/survivorship-compendium-0

- Arias-Ortiz NE, & de Vries E (2018). Health inequities and cancer survival in Manizales, Colombia: A population-based study. Colombia Medica, 49(1), 63–72. 10.25100/cm.v49i1.3629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, & Jemal A (2018). Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 68(6), 394–424. 10.3322/caac.21492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray F, Znaor A, Cueva P, Korir A, Swaminathan R, Ullrich A, Wang S, & Maxwell Parkin D (2014). Planning and developing population-based cancer registration in low- and middle-income settings. IARC Technical Publications No. 43. https://publications.iarc.fr/Book-And-Report-Series/Iarc-Technical-Publications/Planning-And-Developing-Population-Based-Cancer-Registration-In-Low--And-Middle-Income-Settings-2014 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkett VS, & Cleeland CS (2007). Symptom burden in cancer survivorship. Journal of Cancer Survivorship, 1(2), 167–175. 10.1007/s11764-007-0017-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmona-Meza Z, & Parra-Padilla D (2015). Determinantes sociales de la salud: Un análisis desde el contexto colombiano. Salud Uninorte, 31(3), 608–620. 10.14482/sun.31.3.7685 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Vries E, Pardo C, Arias N, Bravo LE, Navarro E, Uribe C, Yepez MC, Jurado D, Garci LS, Piñeros M, Edwards P, Beebe MC, Tangka F, & Subramanian S (2016). Estimating the cost of operating cancer registries: Experience in Colombia. Cancer Epidemiology, 45, 513–519. 10.1016/j.canep.2016.09.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vries E, Uribe C, Pardo C, Lemmens V, Van de Poel E, & Forman D (2015). Gastric cancer survival and affiliation to health insurance in a middle-income setting. Cancer Epidemiology, 39(1), 91–96. 10.1016/j.canep.2014.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demiris G, Oliver DP, & Washington KT (2019). Defining and Analyzing the Problem. Behavioral Intervention Research in Hospice and Palliative Care, 27–39. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-814449-7.00003-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística. (n.d.). Estratificación socioeconómica para servicios públicos domiciliarios. Retrieved February 8, 2020, from https://www.dane.gov.co/index.php/servicios-al-ciudadano/servicios-informacion/estratificacion-socioeconomica

- Departamento Nacional de Estadística. (2019). Boletín Técnico: Pobreza Monetaria en Colombia, Año 2018. Pobreza y Desigualdad. https://www.dane.gov.co/index.php/estadisticas-por-tema/pobreza-y-condiciones-de-vida/pobreza-y-desigualdad/pobreza-monetaria-y-multidimensional-en-colombia-2018

- Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, Parkin DM, Forman D, & Bray F (2015). Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: Sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. International Journal of Cancer, 136(5), E359–E386. 10.1002/ijc.29210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil F, De Vries E, & Wiesner C (2019). Importancia del acceso de los registros de cáncer de base poblacional a las estadísticas vitales: barreras identificadas en Colombia. Revista Colombiana de Cancerología, 23(2), 18–23. 10.35509/01239015.60 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grunfeld E, Earle CC, & Stovall E (2011). A framework for cancer survivorship research and translation to policy. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers and Prevention, 20(10), 2099–2104. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt M, Greenfield S, & Stovall E (Eds.). (2006). From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor. National Academies Press. 10.17226/11468 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Cancerología. (2017). Análisis de Situación del Cáncer en Colombia 2015. https://www.cancer.gov.co/Situacion_del_Cancer_en_Colombia_2015.pdf

- International Agency for Research on Cancer. (2018). Cancer Tomorrow. http://gco.iarc.fr/tomorrow [Google Scholar]

- International Agency for Research on Cancer. (2020). IARC’s Mission: Cancer Research for Cancer Prevention. iarc.fr/about-iarc-mission [Google Scholar]

- Luctkar-flude M, Aiken A, Ann M, & Tranmer J (2015). A comprehensive framework and key guideline recommendations for the provision of evidence- based breast cancer survivorship care within the primary care setting. 32(2), 129–140. 10.1093/fampra/cmu082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao JJ, Armstrong K, Bowman MA, Xie SX, Kadakia R, & Farrar JT (2007). Symptom burden among cancer survivors: Impact of age and comorbidity. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, 20(5), 434–443. 10.3122/jabfm.2007.05.060225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer D, Shapiro C, Jacobson P, & McCabe M (2015). Assuring quality cancer survivorship care: We’ve only just begun. https://ascopubs.org/doi/pdf/10.14694/EdBook_AM.2015.35.e583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Cultura. (2006). Política de diversidad cultural. http://www.mincultura.gov.co/ministerio/politicas-culturales/de-diversidad-cultural/Documents/07_politica_diversidad_cultural.pdf

- Ministerio de Educación. (2018). Tasa de analfabetismo en Colombia a la baja. https://www.mineducacion.gov.co/1759/w3-article-376377.html?_noredirect=1

- Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social de Colombia. (2012). Plan Decenal para el Control del Cáncer en Colombia, 2012–2021. https://www.minsalud.gov.co/sites/rid/Lists/BibliotecaDigital/RIDE/IA/INCA/plan-nacional-control-cancer.pdf

- Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social de Colombia. (2016a). Política de Atención Integral en Salud “Un sistema de salud al servicio de la gente.” Repositorio Institucional Digital Minsalud (RID). https://www.minsalud.gov.co/sites/rid/Lists/BibliotecaDigital/RIDE/DE/modelo-pais-2016.pdf

- Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social de Colombia. (2016b). Resolución 3202 de 2016. https://www.minsalud.gov.co/sites/rid/Lists/BibliotecaDigital/RIDE/DE/DIJ/resolucion-3202-de-2016.pdf

- Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social de Colombia. (2016c). Resolución 429 de 2016. https://www.minsalud.gov.co/Normatividad_Nuevo/Resolución0429de2016.pdf

- Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social de Colombia. (2016d). Rutas integrales de atención en salud (RIAS). https://www.minsalud.gov.co/Paginas/rutas-integrales-de-atencion-en-salud.aspx

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. (2020). NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/survivorship.pdf

- Navarro C, Molina JA, Barrios E, Izarzugaza I, Loria D, Cueva P, Sánchez MJ, Dolores M, & Fernández L (2013). Evaluación externa de registros de cáncer de base poblacional: la Guía REDEPICAN para América Latina. Rev. Panam. Salud Publica, 34(5), 336–342. https://iris.paho.org/handle/10665.2/8855 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nekhlyudov L, Ganz PA, Arora NK, & Rowland JH (2017). Going beyond being lost in transition: A decade of progress in cancer survivorship. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 35(18), 1978–1981. 10.1200/JCO.2016.72.1373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nevidjon B, Rieger P, Miller Murphy C, Quinn Rosenzweig M, McCorkle M, & Baileys K (2010). Filling the Gap: Development of the Oncology Nurse. American Society of Clinical Oncology Journal, 6(1), 2–6. 10.1200/JOP.091072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oncology Nursing Certification Corporation. (2020). Oncology Certified Nurse (OCN). https://www.oncc.org/certifications/oncology-certified-nurse-ocn

- Pardo C, & Cendales R (2018). Cancer incidence estimates and mortality for the top five cancer in Colombia, 2007–2011. Colombia Medica, 49(1), 16–22. 10.25100/cm.v49i1.3596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardo C, & de Vries E (2018). Breast and cervical cancer survival at instituto nacional de cancerología, Colombia. Colombia Medica, 49(1), 102–108. 10.25100/cm.v49i1.2840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act 42 U.S.C. § 18001 (124 STAT. 119). (2010). https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/PLAW-111publ148/pdf/PLAW-111publ148.pdf

- República de Colombia. (1990). Decreto 1760 de 1990. Diario Oficial No. 39.491. http://www.suin-juriscol.gov.co/viewDocument.asp?ruta=Decretos/1345915

- República de Colombia. (1991). Constitución Política de Colombia. http://www.secretariasenado.gov.co/senado/basedoc/constitucion_politica_1991.html

- República de Colombia. (1993). Ley 100 del 1993. Diario Oficial No. 41.148. http://www.comisionseptimasenado.gov.co/salud/SALUDENLEY100DE1993.pdf

- República de Colombia. (1996). Ley 266 de 1996. Diario Oficial No. 42.710. https://www.minsalud.gov.co/sites/rid/Lists/BibliotecaDigital/RIDE/INEC/IGUB/ley-266-de-1996.pdf

- República de Colombia. (2009). Decreto 5017 de 2009. Diario Oficial No. 47.577. http://www.secretariasenado.gov.co/senado/basedoc/decreto_5017_2009.html

- República de Colombia. (2010). Ley 1384 de 2010. Diario Oficial No. 47.685. http://www.secretariasenado.gov.co/senado/basedoc/ley_1384_2010.html

- Rozo P, & Acosta AL (2016). Caracterización Registro Especial de Prestadores de Servicios de Salud (REPS) - IPS. https://www.minsalud.gov.co/sites/rid/Lists/BibliotecaDigital/RIDE/DE/PES/caracterizacion-registro-especial-prestadores-reps.pdf

- Runowicz CD, Leach CR, Henry NL, Henry KS, Mackey HT, Cowens-Alvarado RL, Cannady RS, Pratt-Chapman ML, Edge SB, Jacobs LA, Hurria A, Marks LB, LaMonte SJ, Warner E, Lyman GH, & Ganz PA (2016). American Cancer Society/American Society of Clinical Oncology Breast Cancer Survivorship Care Guideline. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 66(1), 43–73. 10.3322/caac.21319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Q, Smith TG, Michonski JD, Stein KD, Kaw C, & Cleeland CS (2011). Symptom burden in cancer survivors 1 year after diagnosis. Cancer, 117(12), 2779–2790. 10.1002/cncr.26146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The GW Cancer Institute. (n.d.). National Cancer Survivorship Resource Center Toolkit. Retrieved April 5, 2020, from https://smhs.gwu.edu/gwci/survivorship/ncsrc/national-cancer-survivorship-center-toolkit

- Wiesner C (2018). Public health and epidemiology of cancer in Colombia. Colombia Medica, 49(1), 13–15. 10.25100/cm.v49i1.3885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.