Abstract

Background:

Anal cancer disproportionately affects people with HIV (PWH). Highgrade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSIL) are cancer precursors and treating them might prevent anal cancer. Data on adherence to HSIL treatment and surveillance is limited but needed to identify deficiencies of screening strategies.

Methods:

We collected data on high-resolution anoscopy (HRA) attendance and outcomes from 2009 to 2019 in a large urban anal cancer-screening program. Patients with an initial HSIL diagnosis were followed for return for HSIL electrocautery ablation within 6 months of index HSIL diagnosis, and follow-up HRA within 18 months of index HSIL diagnosis. We also evaluated predictors of these outcomes in univariable and multivariable analyses.

Results:

One thousand one hundred and seventy-nine unique patients with an anal HSIL diagnosis were identified and 684 (58%) returned for electrocautery ablation. Of those treated, only 174 (25%) and only 9% of untreated HSIL patients (47 of 495) underwent surveillance HRA within 18 months of index HSIL diagnosis. In multivariable analyses, black patients and PWH regardless of virologic control were less likely to undergo HSIL ablation within 6 months of HSIL diagnosis whereas patients with commercial insurance were more likely to be treated within 6 months of diagnosis. Among treated HSIL patients, PWH with viremia had a lower likelihood of engaging in post-treatment surveillance within 18 months of HSIL diagnosis.

Discussion:

Even in large specialized anal cancer screening programs adherence to HSIL treatment and surveillance is low. Psychosocial and economic determinants of health may impact retention in care. Addressing both personal and structural barriers to patient engagement may improve the effectiveness of anal cancer screening.

INTRODUCTION

Incidence and mortality rates of human papillomavirus (HPV)-associated squamous cell carcinoma of the anus (SCCA) have been rising in the United States.1,2 People living with HIV (PWH) are disproportionately affected with an annual incidence rate of 50 per 100,000; a 19-fold elevated risk compared to the general population.3 The risk further increases among HIV-infected men who have sex with men (MSM) with an annual incidence of 89 per 100,000 and standardized incidence ratio of 39.3–9 The incidence of SCCA is also elevated among HIV-uninfected MSM, with an annual incidence of 19 per 100,000 person-years.10,11

Like cervical cancer, SCCA is preceded by high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSILs). Given the markedly elevated SCCA risk among PWH and emulating the successes of cervical cancer screening, most experts advocate for anal HSIL screening and treatment among PWH. Whether treating anal HSIL ultimately leads to decreased anal cancer rates is currently under investigation; the ANCHOR trial is an ongoing large prospective randomized study comparing HSIL treatment via ablation to observation to determine if surveillance and ablation is related to anal cancer incidence13 Several retrospective studies suggest that treating anal HSIL may prevent at least some anal cancers.14,15 Among PWH the prevalence of anal HSIL is high,a 2012 meta-analysis of HSIL among men with HIV found a pooled prevalence of 29.1% (22.8-35.4%) and among HIV-uninfected men a pooled prevalence of 21.5% (9.2-14.9%).16 Out of concern for scarring, stricture, and mechanical compromise anal HSIL treatment relies on targeted destruction. The tradeoff to this approach are substantial post-treatment recurrence; our cohort noted at median 12.2 months 45% of patients had local recurrence and 60% had recurrence of any type.15 These high rates of recurrence make ongoing surveillance following diagnosis and treatment all the more important.15,17–20

Data on patient adherence to anal HSIL treatment and surveillance is scarce but crucial as utility, performance, and effectiveness of anal cancer screening continue to be debated. Using data from a large, longitudinal HRA database, we evaluated rates and predictors of adherence to treatment and surveillance following diagnosis of anal HSIL.

Methods

The Mount Sinai Anal Dysplasia Program serves a large urban population of PWH and HIV-uninfected MSM. Patients are offered annual anal cytology screening. Cytological diagnoses of atypical cells of undetermined significance (ASCUS) or higher grade abnormalities trigger a referral for HRA which is perfomed following previously described techniques.21 Patients with histologically confirmed HSIL are offered a return visit for electrocautery ablation (EA), preferably within three months of diagnosis. If disease burden is extensive and/or if patients cannot tolerate an office-based procedure, they are referred for surgical fulguration. Patients who undergo HSIL treatment by either modality are advised to return for surveillance six months after treatment. Patients who decline initial treatment are advised to follow up six months after their index HSIL diagnosis for repeat HRA. Since it is not uncommon for these recommended time intervals to be exceeded without losing a patient to care entirely, we expanded the allowable timelines for the purpose of this analysis as outlined below.

From a longitudinal HRA database, we identified patients who attended an initial visit between April 2009 and December 2018. Data were abstracted on demographics, insurance status, HIV clinical variables, HRA results, and retention in care. Approximately 70% of race/ethnicity data were self-reported and the remaining 30% were determined by a published probabilistic approach.22 We identified patients who were diagnosed with HSIL on index HRA and measured the following primary outcomes: (1) return for HSIL treatment within 6 months of diagnosis; (2) follow-up HRA within 18 months of index HSIL diagnosis; and (3) follow-up HRA within 18 months of index HSIL diagnosis for untreated patients. For this analysis we defined “lost to follow-up” as no documented HRA at our testing program during the 18 months after initial HSIL diagnosis. We also captured incident anal cancer diagnoses for each study group. We then compared the proportion of baseline characteristics by outcome groups, testing for differences using χ2 tests. Prior to our analysis, we also selected several of our predictors to fit adjusted logistic regression models predicting the primary outcomes. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS 9.4.

Ethical approval for this retrospective analysis was obtained from the IRB at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

Results

We identified 3,369 patients who underwent at least one HRA. On initial HRA 1,179 (35%) were diagnosed with anal HSIL while 14 (0.4%) were found to have anal cancer (excluded from further analysis). Among those diagnosed with HSIL, at birth 1,054 (90%) were male (of whom 99% self-identified as men who have sex with men and 1% as heterosexual) and 114 (10%) were female. HSIL patients were racially and ethnically diverse: 36% were White, 23% Black, and 25% Hispanic. Among the HSIL cohort, 91% were PWH and the majority had public insurance (51%).

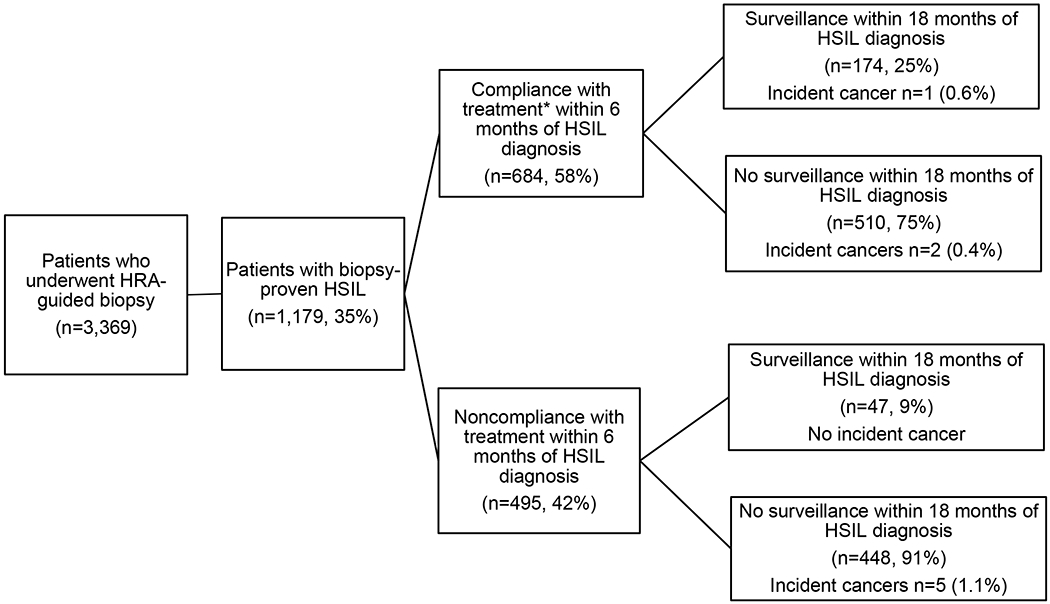

Among 1,179 patients diagnosed with HSIL (Figure 1), 684 (58%) returned for treatment within 6 months of HSIL diagnosis, either receiving office-based EA (n=478, 70%) or fulguration in the operating room by colorectal surgery (n=206, 30%). The median time to treatment following HSIL diagnosis was 56 days. The remaining 495 (42%) did not return for treatment of HSIL within 6 months of initial diagnosis; the range of time to treatment following HSIL diagnosis including those who did return within 6 months was 0-517 days. In the treatment group, 174 (25%) underwent surveillance HRA within 18 months of diagnosis of index HSIL, whereas 510 (75%) did not complete a repeat HRA within 18 months of initial HSIL diagnosis and were considered lost to follow-up after treatment.

Figure 1. Study flowchart.

Treatment and surveillance of anal HSIL patients in New York City anal cancer screening program April 2009 – December 2018. (HSIL: High grade squamous intraepithelial lesion)

*Ablation (n=478, 70%); referred for surgical subspecialty treatment (n=206, 30%)

The majority of untreated HSIL patients (n=448, 91%) did not return for surveillance within 18 months of index diagnosis. A small subset (n= 47, 9%) returned for surveillance HRA during the study period.

There were a total of eight incident anal cancer diagnoses in the cohort. The majority of cancers (5) occurred in untreated HSIL patients who were lost to follow-up for >18 months. Three incident anal cancers occurred in patients treated for anal HSIL; all but one cancer, however, arose in those lost to follow-up after treatment . Median time from index HSIL to cancer diagnosis was 31.7 months (range 6.6 – 37.5)

In unadjusted analyses (Table 1), being Black (odds ratio [OR] 0.47, 95% CI 0.35 –0.65), being of other/unknown race/ethnicity (OR 0.69, 95% CI 0.49 –0.98), current cigarette smoking (OR 0.61, 95% CI 0.46 – 0.81), HIV infection without viremia (OR 0.25, 95% CI 0.14 –0.43) and with viremia (OR 0.20, 95% CI 0.11–0.36) were all significantly associated with a lower likelihood to return for treatment while identifying as MSM (OR 1.6, 95% CI 1.12 – 2.28) and having private/commercial (versus public) insurance was associated withgreater likelihood of returning for HSIL treatment (OR 2.23, 95% CI 1.73 – 2.87). In multivariable analyses Black race (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] 0.61, 95% CI0.43 –0.85), other/unknown race (AOR 0.63, 95% CI 0.43 – 0.92) as well as HIV infection without viremia (AOR 0.28, 95% CI 0.16 – 0.51) and with viremia (AOR 0.23, 95% CI 0.12 – 0.43) were independently associated with not returning for HSIL treatment while private insurance remained a predictor of receiving treatment (AOR 1.83, 95% 1.39 –2.41).

Table 1.

New York City April 2009 – December 2018 cohort characteristics and proportions treated for HSIL, proportions presenting for surveillance within 18 months of treatment of HSIL.

|

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome: Treatment | ||||

|

| ||||

| Characteristic (n=1,179) | Treatment (n=684) | No Treatment (n=495) | Unadjusted OR** (95% CI) | Adjusted OR** (95% CI) |

|

| ||||

| Age *** | ||||

| Mean (SD): 42.3 (11.5) | 41.9 (11.4) | 42.9 (11.5) | 0.87 (0.68 – 1.12) | 0.89 (0.68 – 1.17) |

|

| ||||

| Sexual Practices | ||||

| Heterosexual (n=136, 11.5%) | 65 (47.8%) | 71 (52.2%) | 1.60 (1.12 – 2.28) | 1.15 (0.78 – 1.70) |

| MSM (n=1043, 88.5%) | 619 (59.4%) | 424 (40.7%) | ||

|

| ||||

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| White (n=425, 36.0%) | 278 (65.4%) | 147 (34.6%) | 1 | 1 |

| Black (n=269, 22.8%) | 127 (47.2%) | 142 (52.8%) | 0.47 (0.35 – 0.65) | 0.61 (0.43 – 0.85) |

| Hispanic (n=291, 24.7%) | 169 (58.1%) | 122 (41.9%) | 0.73 (0.54 – 1.00) | 0.91 (0.65 – 1.27) |

| Other/Unknown (n=194, 16.5%) | 110 (56.7%) | 84 (43.3%) | 0.69 (049 – 0.98) | 0.63 (0.43– 0.92) |

|

| ||||

| Smoking | ||||

| Never (n=561, 49.1%) | 349 (62.2%) | 212 (37.8%) | 1 | 1 |

| Former (n=264, 23.1%) | 157 (59.5%) | 107 (40.5%) | 0.89 (0.66 – 1.20) | 0.94 (0.68 – 1.29) |

| Current (n=317, 27.8%) | 159 (50.2%) | 158 (49.8%) | 0.61 (0.46 – 0.81) | 0.76 (0.57 – 1.02) |

|

| ||||

| HIV | ||||

| Negative (n=101, 8.6%) |

85 (84.2%) |

16 (15.8%) |

1 | 1 |

| Positive (n=756, 64.3%) | 430 (56.9%) | 326 (43.1%) | 0.25 (0.14 – 0.43) | 0.28 (0.57 – 1.02) |

| Viremic (n=318, 27.1%) | 165 (51.9%) | 153 (48.1%) | 0.20 (0.11 – 0.36) | 0.23 (0.12 – 0.43) |

|

| ||||

| CD4, Cells/mm3 | ||||

| Median 201 | 202 | 164 | - | - |

|

| ||||

| Insurance Status | ||||

| None or Public (n=763, 64.7%) | 392 (51.4%) | 371 (48.6%) | 2.23 (1.73– 2.87) | 1.83 (1.39 – 2.41) |

| Private (n=416, 35.3%) | 292 (70.2%) | 124 (29.8%) | ||

|

| ||||

| Outcome: Surveillance after Treatment | ||||

|

| ||||

| Characteristic (n=684) | No Surveillance w/in 18 months (n=510) | Surveillance w/in 18 months (n=174) | OR*** (95% CI) | Adjusted OR*** (95% CI) |

|

| ||||

| Age | ||||

| Mean (SD) 41.9 (11.4) | 42.2 (11.2) | 41.4 (12.2) | 0.96 (0.66– 1.38) | 1.09 (0.68 – 1.50) |

|

| ||||

| Sexual Practices | ||||

| †Heterosexual (n=65, 9.5%) | 48 (73.9%) | 17 (26.2%) | 1.10 (0.62 – 1.97) | 1.11 (0.59 – 2.10) |

| MSM (n=619, 90.5%) | 445 (71.9%) | 159 (28.1%) | ||

|

| ||||

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| †White (n=278, 40.6%) | 204 (73.4%) | 74 (26.6%) | 1 | 1 |

| Black (n=127, 18.6%) | 99 (77.2%) | 29 (22.8%) | 0.82 (0.49 – 1.34) | 0.90 (0.52 – 1.54) |

| Hispanic (n=169, 24.7%) | 120 (71.0%) | 49 (29.0%) | 1.13 (0.74 – 1.72) | 1.14 (0.72 – 1.79) |

| Other/Unknown (n=110, 16.1%) | 71 (64.6%) | 39 (34.5%) | 1.51 (0.94 – 2.43) | 1.30 (0.79 – 2.16) |

|

| ||||

| Smoking | ||||

| †Never (n=349, 52.5%) | 247 (70.8%) | 102 (29.2%) | 1 | 1 |

| Former (n=157, 23.6%) | 118 (75.2%) | 39 (24.8%) | 0.80 (0.52 – 1.23) | 0.82 (0.53 – 1.28) |

| Current (n=159, 23.9%) | 116 (73.0%) | 43 (27.0%) | 0.90 (0.59 – 1.37) | 1.0 (0.65 −1.54) |

|

| ||||

| HIV | ||||

| †Negative (n=85, 12.5%) | 53 (62.4%) | 32 (37.7%) | 1 | 1 |

| Positive (n=430, 63.2%) | 309 (71.9%) | 121 (28.1%) | 0.65 (0.40 – 1.06) | 0.68 (0.40 – 1.16) |

| Positive/Viremic (n=165, 24.3%) | 128 (77.6%) | 37 (22.4%) | 0.48 (0.27 – 0.85) | 0.52 (0.28 – 0.96) |

|

| ||||

| CD4, Cells/mm3 | ||||

| Median 202 | 203 | 201 | - | - |

|

| ||||

| Insurance Status | ||||

| †None or Public (n=392, 57.3%) | 287 (73.2.%) | 105 (26.8%) | 1.14 (0.82 – 1.60) | 1.12 (0.77 – 1.63) |

| Private (n=292, 42.7%) | 206 (70.6%) | 86 (29.5%) | ||

Odds ratio for HSIL treatment receipt;

Odds ratio for surveillance within 18 months of HSIL treatment

Age less then median compared to age greater then median

Reference category

For patients treated for HSIL, the only significant predictor of failure of surveillance HRA visit was HIV infection with viremia in both unvariate (OR 0.48, 95% 0.27 – 0.85) and multivariable analyses (AOR 0.52, 95% CI 0.28 – 0.96).

Discussion

In a large cohort at risk for anal cancer we found that adherence to treatment and surveillance following a histological diagnosis of anal HSIL was poor. Only 55% received treatment within 6 months of diagnosis and 75% of treated patients eventually were lost to follow-up. Among untreated HSIL patients, an astounding 91% never engaged in proper surveillance. Factors negatively impacting retention of anal HSIL patients in care included Black race, poor HIV control, and low income noted by public insurance. The clinical and public health implications of our findings are significant as poor adherence to treatment and surveillance of anal HSIL is likely to attenuate potential benefit of screening. These factors may also contribute to health disparities in anal cancer screening, diagnosis, and treatment.

Previous research has reported mixed adherence to treatment and follow-up for anal HSIL. A San Francisco-based study of 246 patients with anal HSIL (79% PLW or with other immunocompromisr) found that less than 20% underwent treatment from 1996 to 2006.23 A slightly higher number (50/155 or 32%) of anal HSIL patients (72% of whom were PWH) from a Boston cohort followed up within 6 months of diagnosis.24 Another New York-based cohort study of MSM with and without HIV foundwhile 90% of anal HSIL patients received treatment within 65 days of HRA, 35% were lost to follow-up within one year.25 Our findings add to the heterogeneous patterns of patient engagement in HSIL care and highlight the challenges of engaging high-risk individuals in appropriate screening and follow-up.

Poor adherence to HSIL surveillance and treatment is of particular concern as 1% of anal HSIL patients in our cohort who received neither treatment or surveillance developed anal cancer. While three HSIL patients who were initially treated progressed, most occurred in the group lost to follow-up after treatment. This is consistent with other studies suggesting that active enrollment in an anal cancer screening program may protect against some but not all anal cancers.14,26

Recently published data show a worrisome trend in anal cancer incidence. Compared with adults born circa 1946, Black men born circa 1986 had a nearly five-fold higher cancer risk.2 Against this backdrop, our finding that Black HSIL patients are significantly less likely to return for HSIL treatment than their non-Black counterparts is particularly troublesome.

Identified barriers to engagement in anal HSIL follow-up include at the patient, provider, and systems factors. Patient demographics, comorbid burden, beliefs about HPV-related disease or HRA, and stigma have all been identified as barriers to anal cancer screening.27–30 Provider-level knowledge and expertise, communication skills, and relationship-building with patients have also been described as predictors of adherence to HRA follow-up.27 Structural and systemic factors also likely influence engagement with HSIL care, including insurance barriers and healthcare system inefficiencies. Studies have also noted that receiving care at an academic medical institution, with difficult scheduling, has impeded HRA follow-up.27,31 Further research is needed to understand how these factors facilitate or hinder appropriate screening, treatment and ongoing surveillance for anal precancers.

There are several limitations of this study. Routine clinical and administrative data were used which may have been irregulary collected. Additionally, we only report on care within our health system and cannot determine if patients sought care elsewhere. Duration of time between HRA and follow-up was likely influenced by several not routinely collected factors and therefore were absent from this analysis. Finally, missing data on race/ethnicity were determined using a probabilistic methodology, which may have misidentified and oversimplified patients’ race/ethnicity. Major strengths of this study are its large size, nearly 10 years of longitudinal data collection, and the diverse cohort at increased anal cancer risk.

In this study we found low adherence to treatment and surveillance for anal precancerous lesions among a cohort at high risk for anal cancer. This highlights important health disparities with those at highest risk least likely to receive treatment or post-treatment surveillance. Evidence-based interventions to improve patient participation in and adherence to anal cancer screening are needed.

References

- 1.Deshmukh AA, Suk R, Shiels MS, et al. Incidence trends and burden of human papillomavirus-associated cancers among women in the United States, 2001-2017. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deshmukh AA, Suk R, Shiels MS, et al. Recent trends in squamous cell carcinoma of the anus incidence and mortality in the United States, 2001–2015. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2020;112(8):829–838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Colón-López V, Shiels MS, Machin M, et al. Anal cancer risk among people with HIV infection in the United States. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2018;36(1):68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vanhaesebrouck A, Pernot S, Pavie J, et al. Factors associated with anal cancer screening uptake in men who have sex with men living with HIV: a cross-sectional study. European Journal of Cancer Prevention. 2020;29(1):1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bouvier A-M, Belot A, Manfredi S, et al. Trends of incidence and survival in squamous-cell carcinoma of the anal canal in France: a population-based study. European Journal of Cancer Prevention. 2016;25(3):182–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wells JS, Holstad MM, Thomas T, Bruner DW. An integrative review of guidelines for anal cancer screening in HIV-infected persons. AIDS patient care and STDs. 2014;28(7):350–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilkinson J, Morris E, Downing A, et al. The rising incidence of anal cancer in E ngland 1990–2010: a population‐based study. Colorectal Disease. 2014;16(7):O234–O239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Machalek DA, Poynten M, Jin F, et al. Anal human papillomavirus infection and associated neoplastic lesions in men who have sex with men: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The lancet oncology. 2012;13(5):487–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shiels MS, Cole SR, Kirk GD, Poole C. A meta-analysis of the incidence of non-AIDS cancers in HIV-infected individuals. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999). 2009;52(5):611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clifford GM, Georges D, Shiels MS, et al. A meta-analysis of anal cancer incidence by risk group: Toward a unified anal cancer risk scale. International journal of cancer. 2021;148(1):38–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van der Zee RP, Richel O, De Vries H, Prins JM. The increasing incidence of anal cancer: can it be explained by trends in risk groups. Neth J Med. 2013;71(8):401–411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fontham ET, Wolf AM, Church TR, et al. Cervical cancer screening for individuals at average risk: 2020 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2020;70(5):321–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Palefsky JM. Screening to prevent anal cancer: current thinking and future directions. Cancer cytopathology. 2015;123(9):509–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Revollo B, Videla S, Llibre JM, et al. Routine Screening of Anal Cytology in Persons With Human Immunodeficiency Virus and the Impact on Invasive Anal Cancer: A Prospective Cohort Study. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2019;71(2):390–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gaisa MM, Liu Y, Deshmukh AA, Stone KL, Sigel KM. Electrocautery ablation of anal high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions: Effectiveness and key factors associated with outcomes. Cancer. 2020;126(7):1470–1479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Machalek DA, Jin F, Poynten IM, et al. Prevalence and risk factors associated with high-grade anal squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSIL)-AIN2 and HSIL-AIN3 in homosexual men. Papillomavirus Research. 2016;2:97–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldstone SE, Johnstone AA, Moshier EL. Long-term outcome of ablation of anal high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions: recurrence and incidence of cancer. Diseases of the colon & rectum. 2014;57(3):316–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Silvera RJ, Smith CK, Swedish KA, Goldstone SE. Anal condyloma treatment and recurrence in HIV-negative men who have sex with men. Diseases of the colon & rectum. 2014;57(6):752–761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stier EA, Abbasi W, Agyemang AF, Valle Alvarez EA, Chiao EY, Deshmukh AA. Brief Report: Recurrence of Anal High-Grade Squamous Intraepithelial Lesions Among Women Living With HIV. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2020;84(1):66–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Long KC, Menon R, Bastawrous A, Billingham R. Screening, Surveillance, and Treatment of Anal Intraepithelial Neoplasia. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2016;29(1):57–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gaisa M, Sigel K, Hand J, Goldstone S. High rates of anal dysplasia in HIV-infected men who have sex with men, women, and heterosexual men. Aids. 2014;28(2):215–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fiscella K, Fremont AM. Use of geocoding and surname analysis to estimate race and ethnicity. Health services research. 2006;41(4p1):1482–1500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pineda CE, Berry JM, Jay N, Palefsky JM, Welton ML. High-resolution anoscopy targeted surgical destruction of anal high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions: a ten-year experience. Diseases of the colon & rectum. 2008;51(6):829–837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Apaydin KZ, Nguyen A, Borba CP, et al. Factors associated with anal cancer screening follow-up by high-resolution anoscopy. Sexually transmitted infections. 2019;95(2):83–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goldstone RN, Goldstone AB, Russ J, Goldstone SE. Long-term follow-up of infrared coagulator ablation of anal high-grade dysplasia in men who have sex with men. Diseases of the colon & rectum. 2011;54(10):1284–1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arens Y, Gaisa M, Goldstone S, et al. Risk of Invasive Anal Cancer in HIV Infected Patients with High Grade Anal Dysplasia: A Population-Based Cohort Study. Diseases of the colon and rectum. 2019;62(8):934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Apaydin KZ, Nguyen A, Panther L, et al. Facilitators of and barriers to high-resolution anoscopy adherence among men who have sex with men: a qualitative study. Sexual health. 2018;15(5):431–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Apaydin KZ, Nguyen A, Borba CP, et al. Factors associated with anal cancer screening follow-up by high-resolution anoscopy. Sex Transm Infect. 2019;95(2):83–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schiphorst AH, Verweij NM, Pronk A, Hamaker ME. Age-related guideline adherence and outcome in low rectal cancer. Diseases of the colon & rectum. 2014;57(8):967–975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Newman PA, Roberts KJ, Masongsong E, Wiley D. Anal cancer screening: barriers and facilitators among ethnically diverse gay, bisexual, transgender, and other men who have sex with men. Journal of gay & lesbian social services. 2008;20(4):328–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kole AJ, Stahl JM, Park HS, Khan SA, Johung KL. Predictors of nonadherence to NCCN guideline recommendations for the management of stage I anal canal cancer. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2017;15(3):355–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]