Abstract

Objectives

Up to 50% of patients with symptomatic knee osteoarthritis (OA) present with neuropathic pain (NP) features. We assessed the impact of NP according to DN4 (Douleurs Neuropathiques 4 questions) score on the response to intra-articular (IA) hyaluronic acid (HA) injections and the effects of HA injections on NP.

Materials and Methods

We conducted a post hoc analysis from a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, noninferiority trial comparing the efficacy of 2 HA in symptomatic knee OA at 24 weeks. At baseline, demographic, anthropometric, radiologic data, and symptoms were recorded. The symptomatic effect of HA was assessed by VAS pain, patient global assessment (PGA), WOMAC, DN4, and OMERACT-OARSI response.

Results

A total of 187 patients were included. NP according to DN4 score was present in 20 patients (10.7%) at baseline. Most common positive DN4 items were tingling (36.9%) and burning (36.4%). NP was associated with WOMAC pain score (P = 0.02). The presence of NP at baseline did not affect the symptomatic improvement after HA injections according to the VAS pain (P = 0.71), PGA (P = 050), WOMAC pain (P = 0.89), WOMAC function (P = 0.52), and rate of OMERACT-OARSI responders (P = 0.21). The prevalence of patients with NP decreased by 50% (n = 10) at 24 weeks after HA injections. Most improved DN4 items were itching (90%), hypoesthesia to pinprick (88%), and burning (50%).

Conclusion

In our study, NP was associated with pain severity, but did not influence the response to IA HA. On the other hand, HA injections reduced some NP features, especially itching, sting hypoesthesia, and burning.

Keywords: neuropathic pain, DN4, hyaluronic acid, knee osteoarthritis

Introduction

Symptomatic knee osteoarthritis (OA) is a highly prevalent condition that affects 5% to 25% of the adult population and dramatically increases with age. 1 It may induce an important pain and disability and, hence, generates massive expenses in terms of public health. 2 Although pain is a major complaint of patients with OA, its origin has not been completely elucidated 3 but could involve both nociceptive and neuropathic mechanisms. 4 This is reinforced by the poor correlation between the structural damage and the pain experienced by patients. 4 In fact, pain in OA is not solely related to the structural changes but might actually be driven by both peripheral and central pain sensitization mechanisms, leading to neuropathic pain (NP).3,5

NP can be characterized by symptoms such as burning, tingling, numbness, sensitivity to touch or pressure, painful cold, electric shocks, and pins and needles.3,6,7 There is increasing evidence regarding its high prevalence in knee or hip OA estimated at 23% according to a systemic review and meta-analysis conducted in 2017. 8 On the other hand, its impact on OA management remains scarcely studied to date. This peculiar phenotype of pain would be associated with worse functional limitation and could consequently represent a severity criterion. 9 Up to 20% of patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty (TKA) still experience pain 1 year later,10,11 which might be explained by the development of NP before or after the surgery. 12 ]. Notably, some studies recently showed that preoperative NP is associated with a higher postoperative pain.13,14

Several questionnaires have been developed and validated for patients with knee OA in order to identify the presence of NP. The DN4, which stands for “Douleurs Neuropathiques 4 questions” and the PainDETECT questionnaires are the most frequently used. 15

Intra-articular (IA) hyaluronic acid (HA) injections are widely used for symptomatic knee OA with a positive effect on pain and functional limitations. 16 However, they are still somehow controversial given the heterogeneity of their response. 17 One hypothesis to explain this heterogeneity is related to the lack of validated predictive factors of response to HA. The phenotype of pain, specially NP could be one of these factors but, interrelations between NP and viscosupplementation (VS) have never been studied.

The HAV-2012 study, a prospective, multicenter, randomized, noninferiority trial comparing 2 different HA preparations in symptomatic knee OA, allowed us to study the possible relation between NP and VS in knee OA. Our primary objective was to assess the impact of NP, as defined by DN4 score, on the response to VS in patients with moderate to severe symptomatic knee OA. Our secondary objectives were to study the correlations between NP and baseline clinical and radiographic characteristics of patients with knee OA, and the effects of HA injections on NP.

Materials and Methods

We conducted a post hoc analysis from the HAV-2012 study, which was a prospective, multicenter, double-blind, randomized, parallel-group trial, conducted in 26 centers in France between October 2012 and April 2014 (registration no. EudraCT 2012-A00570-43). 18 Its purpose was to compare the efficacy and safety of 3 weekly injections of 2 HA preparations in patients with symptomatic knee OA. The injected products were HANOX-M (HAppyVisc, LABRHA SAS, Lyon, France), combining sodium hyaluronate (1-1.5 MDa, 31 mg/2 mL) with mannitol 3.5%, and BioHA (Euflexxa, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Parsippany, 2.4-3.6 MDa, 20 mg/2 mL), which had already been proven effective and safe. The trial complied with the principles of Good Clinical Practice, the Declaration of Helsinki for medical research in humans and the country-specific regulations. Included patients provided an informed consent and were free to withdraw from the study at any time.

Study Design and Patients

The study design of HAV-2012 has been detailed previously. 18 Males and females aged between 40 and 85 years were enrolled if they fulfilled the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria for knee OA, 19 failed to respond to analgesics or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or weak opioids, or were intolerant to them, and graded their pain on walking at baseline between 3 and 8 on an 11-point Likert-type scale (0-10). Bilateral knee radiographs were obtained within 3 months prior to randomization and included 4 views: standing posteroanterior view, Lyon-Schuss view, lateral view, and skyline incidence of the patella. Two scores were assessed: the OARSI score for tibiofemoral (TF) joint space narrowing (JSN) 20 (grade 0: normal, grade 1: mild JSN, grade 2: moderate JSN, grade 3: severe JSN) and the Kellgren-Lawrence (KL) score. 21 Patellofemoral (PF) OA was defined by the presence of patellar definite osteophytes and/or PF JSN. Included patients were those with an OARSI (Osteoarthritis Research Society International) score for TF JSN of 1 to 3, and a KL score of 3 to 4. Only the most painful knee was studied and treated with VS. Patients with bilateral knee OA could be included if their pain on walking score for the contralateral knee was inferior to 3.

Main exclusion criteria were OA flare with knee OA Flare-Ups Score > 7, 22 tibial plateau or femoral condyle bone attrition, symptomatic hip OA, any inflammatory or microcrystal rheumatic disease, excessive varus or valgus knee misalignment (>8°), VS in the target knee in the past 9 months, and systemic or IA corticosteroids use within 3 months prior to randomization.

Some analgesics (acetaminophen, weak opioids [tramadol, codeine]), small doses of ibuprofen (<800 mg daily) and naproxen (<500 mg daily) were allowed during the study but had to be suspended 48 hours prior to each evaluation visit. Topical NSAIDs were permitted, as well as some symptomatic slow-acting drugs for OA (glucosamine, chondroitin sulfate, diacerhein, or avocado/soya unsaponifiables) if they were started more than 2 months before screening and were taken at stable doses. IA steroids were allowed in other joints. Prohibited treatments included high doses of NSAIDs (anti-inflammatory doses), strong opioids, systemic corticosteroids, and IA steroids and HA in the target knee.

Patients were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to receive IA injections of either HAnox-M or Bio-HA. The intention-to-treat (ITT) population included all subjects who met the inclusion criteria, were randomized, received at least 1 injection of HAnox-M or BioHA and had at least 1 postbaseline evaluation.

Baseline and Follow-up Examination

At baseline, demographic and anthropometric data, disease duration and previous treatments for knee OA were recorded, as well as radiological data (OARSI score for JSN and KL score).

Pain and functional limitations were assessed by a visual analogue scale (VAS), a patient global assessment (PGA), and Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC), at baseline, at the time of each injection at weeks (W) 1, 2, and 3, then at the follow-up visits at W12 and W26. WOMAC evaluates OA health status and outcomes with 24 questions23,24 summarized as a total WOMAC score and pain, stiffness, and physical function subscores. Each question was answered with a 5-point Likert-type scale (0 = none, 1 = mild, 2 = moderate, 3 = severe, 4 = extreme), with a maximal score of 96 for the total score (20 for pain, 8 for stiffness, and 68 for physical function subscores). Each score was also converted to a 100-point scale, lower scores indicating better status. Patient global assessment, which evaluated the disease activity, was self-assessed with a 11-point Likert-type scale (0-10) and converted to a 100-point scale. IA effusion was clinically assessed before each injection by experienced physicians (orthopedic surgeon or rheumatologist).

The presence of NP was assessed using the DN4 questionnaire at baseline and at 6 months. The DN4 questionnaire consists in 10 questions about symptoms and signs associated with NP. Seven of these items are based on patient interview and 3 are based on clinical examination. Each question is quoted 0 for no and 1 for yes. A score of 4 or more is considered to reflect the presence of NP. 15

The relative changes in WOMAC score, PGA, and DN4 at 6 months compared with baseline were calculated as (baseline value − 6-month value) / baseline value. According to the criteria published by Pham et al., 25 the OMERACT-OARSI response was defined as a decrease ≥50% and an absolute change ≥20 points in WOMAC pain or function score, or by a decrease ≥20% and an absolute change ≥10 points in at least 2 of the following factors: WOMAC pain, WOMAC function, PGA. 25

Treatments under Study

Both preparations of HA were supplied in prefilled syringes containing 2 mL of HA each. Injections were performed 3 times for each patient, on a weekly basis, by experienced rheumatologists and orthopedic surgeons, based on anatomic landmarks, without ultrasound or fluoroscopy guidance. The physician performing the injections was not blinded to treatment and was not the clinical evaluator. In case of effusion, synovial fluid was aspirated and removed before administering the HA.

Statistical Analysis

All patients from ITT with available data for DN4 at baseline and WOMAC pain at baseline and 6 months were included in this post hoc analysis. Baseline and 6-month follow-up characteristics are presented as number (%) or mean [95% confidence interval]. Student t test was used to compare DN4 scores at baseline and at 6 months. Chi square, Student t test, or Spearman correlation was used to assess the association of NP or DN4 score with demographic and clinical data at baseline and 6 months. A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. XLSTAT 2015 software (Addinsoft, Paris, France) was used for the statistical analysis.

Results

Initially, 226 patients were randomized, but 21 patients were excluded because they did not fulfill the inclusion and/or exclusion criteria. The ITT population included 205 patients, of whom 187 had available DN4 at baseline and WOMAC pain scores at baseline and 6 months. Hence, our post hoc analysis included these 187 patients. As patient characteristics and treatment effectiveness were similar between HAnox-M and Bio-HA groups, their data were pooled. Baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1 . Mean age was 64.7 years. A total of 104 patients (55.6%) were women. Mean disease duration was 46.5 months. Seventy-nine patients (42.2%) had OARSI grade 3 JSN. Mean VAS for pain at baseline was 5.8 while mean WOMAC pain and WOMAC function were, respectively, 9.7 and 27.3.

Table 1.

Patients Characteristics and Symptoms at Baseline and at 6 Months. a

| Population (n = 187) | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 64.7 [63.2-66.2] |

| Sex (female) | 104 (55.6) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.7 [27.0-28.4] |

| Obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) | 51 (27.3) |

| Disease duration (months) | 46.5 [37.1-56.0] |

| Previous IA hyaluronic/corticosteroid injection | 101 (54.0) |

| Kellgren-Lawrence score | |

| Grade 3 | 134 (71.7) |

| Grade 4 | 53 (28.3) |

| OARSI score | |

| Grade 1 | 42 (22.5) |

| Grade 2 | 66 (35.3) |

| Grade 3 | 79 (42.2) |

| Patellofemoral OA | 37 (19.8) |

| Patient global assessment at baseline (0-10) | 6.1 [5.96.4] |

| VAS Pain at baseline (0-10) | 5.8 [5.6-6.0] |

| WOMAC pain at baseline (0-20) b | 9.7 [9.2-10.2] |

| WOMAC function at baseline (0-68) b | 27.3 [25.5-29.2] |

| Patient global assessment at 6 months (0-10) | 3.9 [3.5-4.2] |

| VAS Pain at 6 months (0-10) | 3.1 [2.7-3.5] |

| WOMAC pain at 6 months (0-20) b | 5.4 [4.8-6.0] |

| WOMAC function at 6 months (0-68) b | 15.2 [13.1-17.3] |

| OMERACT-OARSI responders | 117 (70.5) |

ITT = intent-to-treat; BMI, body mass index; WOMAC = Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index; IA = intra-articular.

Data are number of patients (%) or mean [95% CI].

Each WOMAC item was measured on a 5-point Likert scale.

At baseline, 20 patients (10.7%) were found to have NP according to the DN4 definition (DN4 score ≥4). Mean DN4 value at baseline was 1.7 ( Table 2 ). Among the 10 items included in the DN4 questionnaire, most encountered symptoms were numbness (36.9%) and burning (36.4%). Electric shocks were reported by 22.5% of patients. At baseline, 142 of the 187 patients had a DN4 score ≥1, which means that 75.9% of patients reported or were found to have at least 1 of the 10 items composing the DN4 questionnaire.

Table 2.

Douleurs Neuropathiques 4 Questions (DN4) Score and Prevalence of Neuropathic Pain (NP) at Baseline and at 6 Months. a

| Population (n = 187) | Baseline | 6 Months | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| DN4 | 1.7 [1.5-1.9] | 1.0 [0.8-1.2] | <0.0001 |

| Prevalence of NP | 20 (10.7) | 10 (5.4) |

Data are number of patients (%) or mean [95% CI].

No significant association was found between demographic, clinical and radiological characteristics and the presence of NP at baseline with the exception of a negative association with age (P = 0.04) and a positive association with WOMAC pain score (P = 0.02) ( Table 3 ).

Table 3.

Association Between Patients’ Characteristics and NP at Baseline. a

| NP+ (n = 20) | NP− (n = 167) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (female) | 12 (60.0) | 92 (55.1) | 0.68 |

| Age (years) | 60.3 [56.1-64.4] | 65.2 [63.6-66.8] | 0.04 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.9 [26.6-31.3] | 27.5 [26.8-28.3] | 0.24 |

| Disease duration (months) | 60.9 [34.8-86.9] | 44.8 [34.7-54.8] | 0.30 |

| Kellgren-Lawrence score (grade 4) | 7 (35.0) | 46 (27.5) | 0.48 |

| OARSI score (grade 3) | 10 (50.0) | 69 (41.3) | 0.46 |

| Patellofemoral OA | 7 (35.0) | 30 (18.0) | 0.07 |

| VAS pain at baseline (0-10) | 6.0 [5.3-6.6] | 5.8 [5.6-6.0] | 0.67 |

| Patient global assessment at baseline (0-10) | 6.3 [5.5-7.1] | 6.1 [5.9-6.3] | 0.59 |

| WOMAC pain at baseline (0-20) b | 11.4 [10.3-12.4] | 9.5 [9.0-10.0] | 0.02 |

| WOMAC function at baseline (0-68) b | 31.1 [26.1-36.0] | 26.9 [25.0-28.8] | 0.17 |

NP = neuropathic pain; BMI = body mass index; OARSI, Osteoarthritis Research Society International; VAS, visual analogue scale; WOMAC = Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index.

Data are number of patients (%) or mean [95% CI].

Each WOMAC item was measured on a 5-point Likert scale.

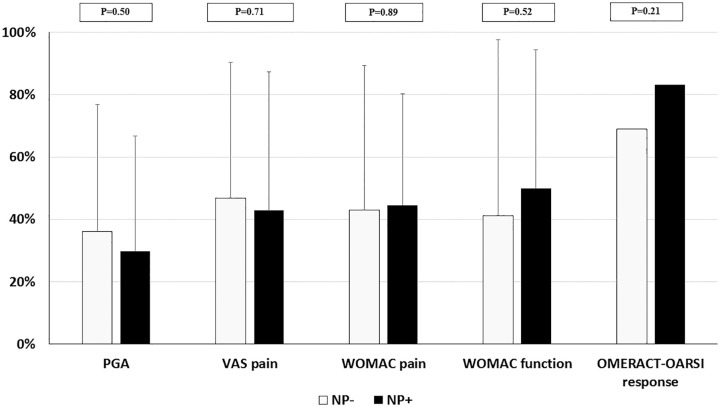

At 6 months, there was a 2.7 point-decrease in mean VAS pain values while mean PGA improved by 2.2 points. WOMAC pain and function were also reduced at 6 months, with mean levels decreasing, respectively, by 4.7 and 12.1 points. Overall, 70.5% of patients were considered as OMERACT-OARSI responders. The presence of NP at baseline did not significantly affect the improvement and response rate after VS. Indeed, at 6 months, PGA and VAS pain, respectively, decreased by 29.8% and 42.9% in patients with NP compared with 36.2% and 46.8% in those without NP, with P values of 0.50 and 0.71. The respective improvements in WOMAC pain and function and OMERACT-OARSI response were 44.6%, 50%, and 83.3% in those who had NP at baseline, while they reached 43.1%, 41.1%, and 68.9% in the absence of NP, with respective P values of 0.89, 0.52, and 0.21 ( Fig. 1 ).

Figure 1.

Clinical improvement at 6 months according to the presence of neuropathic pain. Results are shown as mean percentage (±standard deviation) of improvement between baseline and 6 months. NP, neuropathic pain; PGA, patient global assessment; OARSI, Osteoarthritis Research Society International; VAS, visual analogue scale; WOMAC = Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index.

However, the prevalence of NP was decreased by 50% at 6 months after IA injection of HA. Indeed, while there were 20 patients (10.7%) with a NP according to the DN4 at baseline, this number decreased to 10 (5.4%) at 6 months post-VS. Only 5 patients (25.0%) with NP at baseline still had 1 at 6 months. The absolute value of DN4 significantly decreased at 6 months (1.0 vs. 1.7, P < 0.0001) ( Table 2 ). Similarly, among the 142 patients who had at least 1 NP component at screening (DN4 ≥ 1), 63 patients (44.4%) had a complete resolution of NP symptoms 6 months after VS (DN4 = 0) (data not shown). The improvement of NP was significantly associated with the improvement of VAS, PGA, and WOMAC scores (P < 0.001) (data not shown).

Interestingly, not all items included in the DN4 improved equally. In fact, itching, although relatively rare (5.3% at baseline), improved dramatically with only 1 patient (0.5%) still reporting it at 6 months (90% improvement). Similarly, hypoesthesia to pinprick decreased by 88% with only 1 patient (0.5%) affected at 6 months versus 9 patients (4.8%) at baseline. Burning, which was one of the most frequently encountered complaints at screening (36.4% of patients), was considerably improved by VS. Indeed, it was decreased by 50% with only 18.2% of patients reporting it after 6 months ( Table 4 ).

Table 4.

Prevalence of Symptoms of Neuropathic Pain. a

| DN4 Items | At Baseline | At 6 Months |

|---|---|---|

| Burning | 68 (36.4) | 35 (18.8) |

| Painful cold | 12 (6.4) | 11 (6.0) |

| Electric shocks | 42 (22.5) | 23 (12.3) |

| Tingling | 27 (14.4) | 18 (9.6) |

| Pins and needles | 31 (16.6) | 30 (16.0) |

| Numbness | 69 (36.9) | 44 (23.5) |

| Itching | 10 (5.3) | 1 (0.5) |

| Hypoesthesia to touch | 18 (9.6) | 6 (3.2) |

| Hypoesthesia to prick | 9 (4.8) | 1 (0.5) |

| Brushing | 33 (17.6) | 18 (9.8) |

DN4 = Douleurs Neuropathiques 4 Questions.

Data are number of patients (%).

Discussion

This post hoc analysis from the HAV-2012 study, a prospective randomized controlled trial, showed that the presence of NP in knee OA did not significantly affect the response to IA HA injections. It did, however, correlate with higher levels of pain at screening and, interestingly, it was improved by VS.

HA injections are largely used in knee OA, despite the lack of consensus among the available international recommendations for management of knee OA. 26 Yet VS has a proven effect on pain in knee OA, which tends to be rather slow but long-lasting.16,27,28 Nevertheless, although the effect of IA injections of HA on pain have been extensively studied, there are few data concerning the potential predictive factors of HA response. Indeed, there is a large variety of HA preparations that could be used for knee OA. However, their overall efficacy is considered moderate, while their cost is rather high. Moreover, they carry a small risk of infection—especially due to the IA injection itself. For all these reasons, being able to identify the potentially good responders seems quite important. Additionally, identifying those who would probably not benefit from HA injections might allow physicians to provide a better management for their knee OA patients, particularly to identify those who should undergo a surgery without wasting time trying HA.

Based on the same cohort, we previously reported a negative impact of obesity and radiographic severity on OMERACT-OARSI response after HA injections. 29 In our best knowledge, no data has been published regarding the potential impact of NP on HA response despite the fact that up to 25% of patients with symptomatic knee OA might have NP features. 5 In our study, the presence of NP did not impact the response of HA, irrespective of the evaluated criterion (PGA, VAS, WOMAC, OMERACT-OARSI response). In fact, the only intervention for which the impact of NP has been assessed, is TKA. While this surgery has been considerably developed with a constantly increasing number of procedures, 30 up to 20% of patients still report chronic postoperative pain, despite the absence of prosthesis defect.11,13 Interestingly, several studies have shown that up to 1 in 5 patients undergoing total knee replacement might still experience NP after the surgery.10-12 In parallel, a recent trial showed that patients with NP undergoing a TKA had higher postoperative pain scores than those with nociceptive pain. 13

Similarly, the effect of HA injections on NP has never been studied in patients with knee OA. In our study, we found that the prevalence of NP decreased by 50% at 6 months after HA injections and 44.4% of patients had a complete resolution of neuropathic symptoms (DN4 = 0). However, given the absence of placebo group, we cannot conclude that this improvement is specifically related to the HA injections.

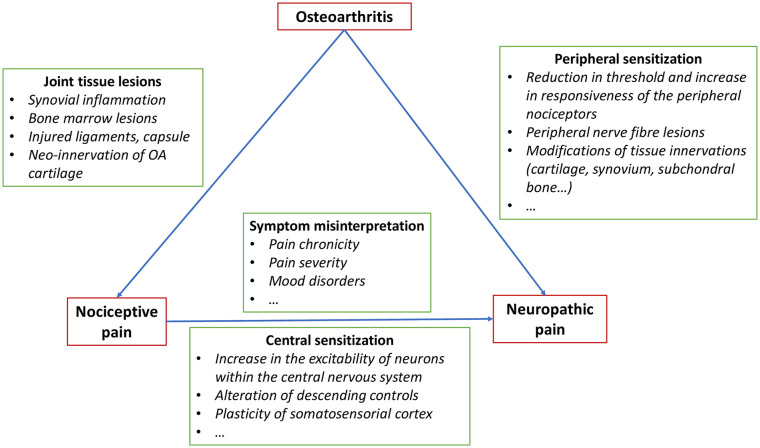

Also of note, the extent of NP improvement was significantly correlated with the improvement of VAS, PGA, and WOMAC score after VS (P < 0.001) (data not shown). In accordance with the association between WOMAC pain and NP at baseline, these results suggest a correlation between the presence of neuropathic symptoms and the severity of nociceptive pain. This correlation could be explained by central pain sensitization related to an increase in the excitability of neurons within the central nervous system, an alteration of descending controls but also a plasticity of somatosensorial cortex ( Fig. 2 ).4,5,31-33 However, we can also suppose that the severity and the chronicity of OA nociceptive pain, frequently associated with mood disorders, could induce a misinterpretation of symptoms by patients, and so explain a part of porosity between nociceptive and neuropathic symptoms especially in the absence of objective assessment of neurogenic impairment.34-36 In our study, the presence of NP was evaluated using the DN4 questionnaire, which has been previously validated as an efficient tool to assess NP. 15 However, there is no gold standard for this purpose. DN4 is not the only score evaluating NP. For instance, the painDETECT questionnaire is also widely used. It has originally been developed and validated for NP in chronic low back pain, 37 and a modified version has been adapted for use in knee OA. 5 The painDETECT scores range from 0 to 38, with scores ≥19 indicating “likely neuropathic pain” or “neuropathic pain–like symptoms,” scores ≤13 corresponding to nociceptive pain, and values in-between considered indicative of a mixed pain phenotype. 37 It has shown high sensitivity and specificity 38 but is not the gold standard and still remains controversial. In fact, while there are studies supporting its use for stratifying patients into those with NP and those with nociceptive pain, 14 there are concerns about its validity, especially the modified version used for knee OA. 34 Moreover, self-reported questionnaires may not be reliable and must always be correlated to clinical examination of the patient.34,39,40 The same applies to another tool used for screening for NP, the Leeds Assessment of Neuropathic Symptoms and Signs (S-LANSS) questionnaire, which is also a patient-reported measure and, though it has been validated, 5 might raise the same concerns [34]. To our knowledge, there are no studies in the literature that have specifically searched for issues raised by the DN4 or proven any invalid or incorrect results obtained with this questionnaire. This could actually be due to the fact that the DN4 has been less employed than the painDETECT, especially by non-French researchers, nonetheless, there are no solid data questioning its validity.

Figure 2.

Pathophysiological hypothesis to explain associations between nociceptive and neuropathic pain in osteoarthritis (OA).4,5,31-33

The mechanism of action of IA injections of HA and the molecular pathways underneath its articular effects are still incompletely elucidated. The effect of HA could be both direct and indirect. Indeed, it is thought to exert lubricating action and to restore, though partially and transitorily, the protective rheological buffer, while also having anti-inflammatory effects on articular cartilage and synovial membrane.41,42 Moreover, the increase in cartilage shock absorbing capacity during joint movement would reduce the force transmitted to all joint tissues, including nociceptive nerve endings.43-45 A possible additional effect of HA on peripheral nociceptor activity has been suggested in some in vitro and animal experiments. Indeed, a study found that the analgesic effect of HA, when injected in joints, could be partially explained by an inhibitory chemical action on peripheral nociceptors. 46 These complicated molecular actions of HA exerted in nociceptors could include modulation of specific vanilloid and capsaicin receptors and regulation of intracellular calcium responses. 46

Our study has some limitations. First, it is an ancillary study of a previous trial, and this post-hoc analysis was not included in the original design of HAV-2012. Moreover, we did not use objective tools to evaluate mechanical, vibration, or thermal sensitivity, which are altered in NP. 47 The size of our study population was limited. We only included 187 patients. Furthermore, since it only included the patients for whom DN4 and WOMAC pain scores were available at baseline and at 6 months, we cannot exclude a selection bias. Additionally, there was no placebo arm, since the HAV-2012 study aimed to compare 2 different HA preparations. Both treatment groups received HA during the study, hence, it was not possible to compare the effects of HA with those of IA placebo on NP in knee OA. Moreover, analgesics and medications prescribed for neuropathic pain were not forbidden during the course of the study, which might have impacted the nociceptive and neuropathic pain relief.

Notably, the prevalence of NP in our sample was lower than what is found in the literature. Indeed, in the cohort studied by Hochman et al. 5 in 2011, up to 25% of patients with symptomatic knee OA could potentially have NP features, while a recent study, conducted in 2018, found that 42% of women and 27% of men with knee OA could have “possible or likely” NP. 3 Importantly, these studies used, respectively, a modified version of the painDETECT (coadministered with the S-LANSS) 5 and the painDETECT questionnaire, 3 while we used the DN4.

On the other hand, this study has many strengths. It is a double-blind randomized controlled trial and, compared with retrospective observational studies, the design of HAV-2012 allowed a more rigorous data collection. More important, it is, to our knowledge, the first study to address the potential impact of NP on the response to IA injection of HA, and the effect of VS on NP in knee OA.

In conclusion, even though the prevalence of NP, as defined by the DN4, was somehow lower than expected, NP components were highly prevalent and were found to improve following VS. However, NP was not found to impact the response to IA injections of HA in knee OA. Further trials would be needed to better study this potential association.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: ET, MC, and FE contributed to the design of the study, the analysis and interpretation of data. They wrote the manuscript. XC and TC contributed to the design of the study, the analysis and interpretation of data. They participated substantially to the reviewing of the manuscript before submission. All authors approved the version submitted.

Acknowledgments and Funding: Authors acknowledge Labrha SA, Lyon, France for making available the database. The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: ET and MC have no competing interests. XC received fees as an expert from Labhra, Sanofi, Pfizer, and IBSA and for travel expenses for congress from Expanscience and Nordic Pharma. TC received fees from Labhra, Ossür, and Sanofi. FE received fees from RegenLab.

Ethical Approval: Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Lyon Sud-EST IV.

Informed Consent: The included patients provided an informed consent and were free to withdraw from the study at any time.

Trial Registration: The initial trial was registered with number EudraCT 2012-A00570-43.

ORCID iDs: Magda Choueiri  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5627-7605

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5627-7605

Thierry Conrozier  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0353-6292

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0353-6292

Florent Eymard  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2758-5216

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2758-5216

References

- 1. Pereira D, Peleteiro B, Araújo J, Branco J, Santos RA, Ramos E. The effect of osteoarthritis definition on prevalence and incidence estimates: a systematic review. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2011;19:1270-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Glyn-Jones S, Palmer AJR, Agricola R, Price AJ, Vincent TL, Weinans H, et al. Osteoarthritis. Lancet. 2015;386:376-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Power JD, Perruccio AV, Gandhi R, Veillette C, Davey JR, Syed K, et al. Neuropathic pain in end-stage hip and knee osteoarthritis: differential associations with patient-reported pain at rest and pain on activity. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2018;26:363-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mease PJ, Hanna S, Frakes EP, Altman RD. Pain mechanisms in osteoarthritis: understanding the role of central pain and current approaches to its treatment. J Rheumatol. 2011;38: 1546-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hochman JR, Gagliese L, Davis AM, Hawker GA. Neuropathic pain symptoms in a community knee OA cohort. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2011;19:647-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hochman JR, French MR, Bermingham SL, Hawker GA. The nerve of osteoarthritis pain. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2010;62:1019-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bennett MI, Attal N, Backonja MM, Baron R, Bouhassira D, Freynhagen R, et al. Using screening tools to identify neuropathic pain. Pain. 2007;127:199-203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. French HP, Smart KM, Doyle F. Prevalence of neuropathic pain in knee or hip osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2017;47:1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Blikman T, Rienstra W, van Raay JJAM, Dijkstra B, Bulstra SK, Stevens M, et al. Neuropathic-like symptoms and the association with joint-specific function and quality of life in patients with hip and knee osteoarthritis. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0199165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pinto PR, McIntyre T, Ferrero R, Araújo-Soares V, Almeida A. Persistent pain after total knee or hip arthroplasty: differential study of prevalence, nature, and impact. J Pain Res. 2013;6:691-703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wylde V, Hewlett S, Learmonth ID, Dieppe P. Persistent pain after joint replacement: prevalence, sensory qualities, and postoperative determinants. Pain. 2011;152:566-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fitzsimmons M, Carr E, Woodhouse L, Bostick GP. Development and persistence of suspected neuropathic pain after total knee arthroplasty in individuals with osteoarthritis. PM R. 2018;10:903-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kurien T, Arendt-Nielsen L, Petersen KK, Graven-Nielsen T, Scammell BE. Preoperative neuropathic pain-like symptoms and central pain mechanisms in knee osteoarthritis predicts poor outcome 6 months after total knee replacement surgery. J Pain. 2018;19:1329-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Soni A, Wanigasekera V, Mezue M, Cooper C, Javaid MK, Price AJ, et al. Central sensitization in knee osteoarthritis: relating presurgical brainstem neuroimaging and pain DETECT-based patient stratification to arthroplasty outcome. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71:550-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bouhassira D, Attal N, Alchaar H, Boureau F, Brochet B, Bruxelle J, et al. Comparison of pain syndromes associated with nervous or somatic lesions and development of a new neuropathic pain diagnostic questionnaire (DN4). Pain. 2005;114:29-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Richette P, Chevalier X, Ea HK, Eymard F, Henrotin Y, Ornetti P, et al. Hyaluronan for knee osteoarthritis: an updated meta-analysis of trials with low risk of bias. RMD Open. 2015;1:e000071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rutjes AWS, Jüni P, da Costa BR, Trelle S, Nüesch E, Reichenbach S. Viscosupplementation for osteoarthritis of the knee: a Systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157:180-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Conrozier T, Eymard F, Afif N, Balblanc J-C, Legré-Boyer V, Chevalier X. Safety and efficacy of intra-articular injections of a combination of hyaluronic acid and mannitol (HAnOX-M) in patients with symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. Knee. 2016;23:842-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Altman R, Asch E, Bloch D, Bole G, Borenstein D, Brandt K, et al. Development of criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis: classification of osteoarthritis of the knee. Diagnostic and Therapeutic Criteria Committee of the American Rheumatism Association. Arthritis Rheum. 1986;29:1039-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Altman RD, Gold GE. Atlas of individual radiographic features in osteoarthritis, revised. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2007;15(Suppl A):A1-A56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kellgren JH, Lawrence JS. Radiological assessment of osteo-arthrosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1957;16:494-502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Marty M, Hilliquin P, Rozenberg S, Valat JP, Vignon E, Coste P, et al. Validation of the KOFUS (Knee Osteoarthritis Flare-Ups Score). Joint Bone Spine. 2009;76:268-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Marot V, Murgier J, Carrozzo A, Reina N, Monaco E, Chiron P, et al. Determination of normal KOOS and WOMAC values in a healthy population. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2019;27:541-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bellamy N, Buchanan WW, Goldsmith CH, Campbell J, Stitt LW. Validation study of WOMAC: a health status instrument for measuring clinically important patient relevant outcomes to antirheumatic drug therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. J Rheumatol. 1988;15:1833-40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pham T, van der Heijde D, Altman RD, Anderson JJ, Bellamy N, Hochberg M, et al. OMERACT-OARSI Initiative: Osteoarthritis Research Society International set of responder criteria for osteoarthritis clinical trials revisited. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2004;12:389-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Maheu E, Bannuru RR, Herrero-Beaumont G, Allali F, Bard H, Migliore A. Why we should definitely include intra-articular hyaluronic acid as a therapeutic option in the management of knee osteoarthritis: results of an extensive critical literature review. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2019;48:563-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Maheu E, Rannou F, Reginster JY. Efficacy and safety of hyaluronic acid in the management of osteoarthritis: evidence from real-life setting trials and surveys. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2016;45:528-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nguyen C, Lefèvre-Colau MM, Poiraudeau S, Rannou F. Evidence and recommendations for use of intra-articular injections for knee osteoarthritis. Ann Phys Rehab Med. 2016;59:184-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Eymard F, Chevalier X, Conrozier T. Obesity and radiological severity are associated with viscosupplementation failure in patients with knee osteoarthritis: predictive factors of viscosupplementation. J Orthop Res. 2017;35:2269-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kurtz S. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:780-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Thakur A, Dickenson AH, Baron R. Osteoarthritis pain: nociceptive or neuropathic? Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2014;10:374-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Oteo-Alvaro A, Ruiz-Iban MA, Miguens X, Stern A, Villoria J, Sanchez-Magro I. High prevalence of neuropathic pain features in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a cross-sectional study. Pain Pract. 2015;15:618-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Trouvin AP, Perrot S. Pain in osteoarthritis. Implications for optimal management. Joint Bone Spine. 2018;85:429-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hasvik E, Haugen AJ, Grøvle L. Call for caution in using the Pain DETECT Questionnaire for patient stratification without additional clinical assessments: comment on the article by Soni et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71:1201-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Goldenberg DL. The interface of pain and mood disturbances in the rheumatic diseases. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2010;40:15-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Torta R, Leraci V, Zizzi F. A review of the emotional aspects of neuropathic pain: from comorbidity to co-pathogenesis. Pain Ther.2017;6:11-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Freynhagen R, Baron R, Gockel U, Tölle TR. pain DETECT: a new screening questionnaire to identify neuropathic components in patients with back pain. Curr Med Res Opin. 2006;22:1911-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Freynhagen R, Tölle TR, Gockel U, Baron R. The painDETECT project—far more than a screening tool on neuropathic pain. Curr Med Res Opin. 2016;32:1033-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hansson P, Haanpää M. Diagnostic work-up of neuropathic pain: computing, using questionnaires or examining the patient? Eur J Pain. 2007;11:367-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mathieson S, Maher CG, Terwee CB, Folly de, Campos T, Lin CWC. Neuropathic pain screening questionnaires have limited measurement properties. A systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015;68:957-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Loeser RF, Goldring SR, Scanzello CR, Goldring MB. Osteoarthritis: a disease of the joint as an organ. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:1697-707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Malemud CJ, Islam N, Haqqi TM. Pathophysiological mechanisms in osteoarthritis lead to novel therapeutic strategies. Cells Tissues Organs. 2003;174:34-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gomis A, Pawlak M, Balazs EA, Schmidt RF, Belmonte C. Effects of different molecular weight elastoviscous hyaluronan solutions on articular nociceptive afferents. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:314-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gomis A, Miralles A, Schmidt RF, Belmonte C. Nociceptive nerve activity in an experimental model of knee joint osteoarthritis of the guinea pig: effect of intra-articular hyaluronan application. Pain. 2007;130:126-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Pozo MA, Balazs EA, Belmonte C. Reduction of sensory responses to passive movements of inflamed knee joints by hylan, a hyaluronan derivative. Exp Brain Res. 1997;116:3-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Caires R, Luis E, Taberner FJ, Fernandez-Ballester G, Ferrer-Montiel A, Balazs EA, et al. Hyaluronan modulates TRPV1 channel opening, reducing peripheral nociceptor activity and pain. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Cruccu G, Truini A. Tools for assessing neuropathic pain. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]