Abstract

Introduction

Injuries to articular cartilage have a poor spontaneous repair potential and no gold standard treatment exist. Particulated cartilage, both auto- and allograft, is a promising new treatment method that circumvents the high cost of scaffold- and cell-based treatments.

Materials and Methods

A comprehensive database search on particulated cartilage was performed.

Results

Fourteen animal studies have found particulated cartilage to be an effective treatment for cartilage injuries. Many studies suggest that juvenile cartilage has increased regenerative potential compared to adult cartilage. Sixteen clinical studies on 4 different treatment methods have been published. (1) CAIS, particulated autologous cartilage in a scaffold, (2) Denovo NT, juvenile human allograft cartilage embedded in fibrin glue, (3) autologous cartilage chips—with and without concomitant bone grafting, and (4) augmented autologous cartilage chips.

Conclusion

Implantation of allogeneic and autologous particulated cartilage provides a low cost and effective treatment alternative to microfracture and autologous chondrocyte implantation. The methods are promising, but large randomized controlled studies are needed.

Keywords: particulated cartilage, minced cartilage, cartilage chips, cartilage repair, repair, particulated juvenile articular cartilage

Introduction

The use of particulated articular cartilage (minced cartilage or cartilage chips) is emerging as a treatment modality in articular cartilage repair to overcome the current challenges in cost and long-term outcome for marrow stimulation and cell-based cartilage repair. 1 The surge of these collective methods has been motivated by both encouraging clinical and experimental results, but also the need for a cheaper and potentially more cost-effective treatment for articular cartilage lesions.

Microfracture-based treatments are widely accepted as an effective gold standard for small and intermediate sized cartilage defects as they provide a predictable clinical improvement in the majority of patients. 2 However, the repair tissue is not hyaline cartilage, but rather a mixture of fibrous tissue and fibrocartilage, and the early good outcome tends to deteriorate in long-term follow-up.3,4 For larger cartilage defects the most promising method in short- and long-term follow-up studies has been autologous chondrocyte implantation (ACI) treatments. Most reports on clinical outcomes following ACI-based treatments are on small or intermediate sized defects, 5 but despite relatively good results, the high cost of commercial cell culture and 2-step surgery have severely limited their use. Recently, the high cost of up to €20-30,000 per chondrocyte culture has resulted in public health care providers in many countries completely abandoning their use. 6 Instead, stand-alone scaffolds and plugs has provided an alternative that is financially more acceptable and with short-term outcomes comparable to microfracture. However, concerns regarding their regenerative potential and repair tissue morphology and consequently the long-term outcomes have been raised.7-9

The clinical use of particulated cartilage for cartilage defects was first described in 1983 by Albrect et al. 10 In 2006, when Lu and Binette observed migration of chondrocytes from the extracellular matrix of cartilage chips during the chondrocyte extraction, Depuy Mitek initiated a series of in vitro studies that lead to the development of the commercial cartilage autograft implantation system (CAIS). 11 The efficacy and safety of CAIS was then confirmed in a proof-of-concept and safety clinical trial, and the encouraging results led to the initiation of a randomized controlled trial comparing CAIS to microfracture in ICRS (International Cartilage Repair Society) grade III to IV lesions in the knee. Unfortunately, financial considerations and slow participant enrolment lead to sponsorship withdrawal by the company and subsequently an early termination of the trial. Nonetheless, two-year data were published highlighting the potential when treating defects of approximately 3 cm2 in both the femoral condyles and trochlea. 12

In 2007, a new cartilage chip-based product, the Denovo NT was introduced. Denovo NT utilizes the increased chondrogenic potential of juvenile articular cartilage by implanting juvenile articular cartilage fragments in chondral defects. The use of allogenic juvenile cartilage makes Denovo NT an off-the-shelf product. A large number of patients have been treated and the clinical results are promising. 13

This recently motivated the group behind the present review to follow-up on the encouraging findings from previous studies. This application allowed the use of techniques and technology readily available in any conventional surgical setting by simply cutting autologous cartilage biopsies into 0.25 to 0.5 mm3 chips using a scalpel in the operating theatre and embedding these in fibrin glue before placing them in the debrided defect.

The increasing number of publications describing the use of particulated cartilage for the repair of cartilage defects in the knee motivated the present literature review. Hence, the scope is to review the current experimental and clinical literature on the use of particulated autologous and allogenous cartilage for articular cartilage repair.

Materials and Methods

Article Identification and Selection

Literature search was performed using the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, PubMed, Scopus, and MEDLINE (1980 to 2019).

The queries were performed in January 2020. The literature search strategy included the following: Search ((CAIS [All Fields] OR “cartilage autograft implantation system” [All Fields]) OR (ADTT [All Fields] OR “autologous dual tissue transplantation”[All Fields]) OR (PJAC [All Fields] OR “particulated juvenile articular cartilage”[All Fields]) OR (CAFRIMA [All Fields] OR “cartilage autologous fragment implantation matrix augmented”[All Fields]) AND (“allografts”[MeSH Terms] OR “allografts”[All Fields] OR “allograft”[All Fields]) OR (“autografts”[MeSH Terms] OR “autografts”[All Fields] OR “autograft”[All Fields])) AND (“chondral”[All Fields] OR “osteochondral”[All Fields] AND “cartilage”[All Fields]) OR “articular cartilage”[All Fields]).

Inclusion criteria were as follows: clinical and experimental outcomes of particulated cartilage for the treatment of chondral and osteochondral defects in articular joints in human and large animal studies, English language, minimum follow-up of 6 months for all patients in the cohort, and minimum study size of 5 patients.

We excluded cadaveric studies, biomechanical reports, editorial articles, case reports, literature reviews, surgical technique descriptions, instructional courses, studies comparing different techniques in which isolated particulated cartilage subgroups were not reported independently.

Two independent reviewers (MLO and NLB) performed a review of the abstracts from all identified articles. Full-text articles were obtained for review if necessary, to allow for further assessment of inclusion and exclusion criteria. Additionally, all references from the included studies were reviewed and reconciled to verify that no relevant articles were missing from the review.

Results

Selected In Vitro Studies

In 2000, Qiu et al. 14 studied outgrowth of chondrocytes from cartilage explants. The authors found that chondrocyte outgrowth took more than 30 days while prior treatment with collagenase reduced the chondrocyte migration time to 3 days. The 2006 Lu et al. 11 study confirmed that chondrocytes could migrate from the extracellular matrix and induce cartilage repair in vivo and in 2009 Sage et al. 15 demonstrated that the addition of fibrin glue to human septal cartilage chips, increased cell proliferation and DNA and GAG (glycosaminoglycan) content.

There is substantial evidence suggesting that juvenile cartilage has increased chondrogenic potential. As cartilage ages, an increased calcification of the tissue is seen. 16 In addition, there is a decrease in proteoglycan synthesis and a decreased response to growth factor stimulation with increased age.17,18 Namba et al. 19 made superficial knee cartilage defects in lamb fetuses in utero, and found complete regeneration without scar tissue, after 28 days. Adkisson et al. 20 found that “proteoglycan content in neocartilage produced by juvenile chondrocytes was 100-fold higher than in neocartilage produced by adult cells. Collagen type II and type IX mRNA in fresh juvenile chondrocytes were 100- and 700-fold higher, respectively, than in adult chondrocytes.” These results were substantiated by Liu et al. 21 who cultured adult and juvenile bovine cartilage for 4 weeks and found that “Compared with adult cartilage, juvenile bovine cartilage demonstrated a significantly greater cell density, higher cell proliferation rate, increased cell outgrowth, elevated glycosaminoglycan content, and enhanced matrix metallopeptidase 2 activity.”

Bonasia et al. 18 demonstrated that cultured juvenile cartilage chips and a co-culture of juvenile and adult cartilage chips performs better than adult cartilage chips alone in terms of matrix production and safranin o and collagen type II staining. Marmotti et al. 22 found an increase in chondrocyte outgrowth from cartilage chips when adding transforming growth factor–β1 (TGF-β1) and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) to the cultures, and in a 2015 study, Bonasia et al. 23 found a correlation between smaller cartilage fragments and increased extra cellular matrix production.

Animal Studies

A comprehensive literature search returned 14 in vivo studies reporting the use of fragmented cartilage. Twelve studies described use of autologous cartilage fragments, 1 study described the use of particulated juvenile allograft cartilage (PJAC), and 1 study compared the two ( Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Experimental Studies on Particulated Cartilage. a

| Authors | Model | Animals/Defects | Treatment | Control Group(s) | Outcome | Follow-up (Weeks) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Albrecht et al. (1983) | Rabbit | 45/75 | (1) Autologous cartilage fragments. (2) Autologous cartilage fragments + collagen foam | (1) Empty control. (2) Collagen foam. (3) Collagen foam + fibrin glue | Histology | 40 |

| Lu et al. (2006) | Goat | 8/15 | Autologous cartilage fragments + PGA/PCL scaffold | (1) Empty control. (2) Scaffold alone | Histology (O’Driscoll scale) | 26 |

| Lind et al. (2008) | Goat | 8/16 | Autologous cartilage fragments + Collagen type 1 and 3 scaffold | Chondrocytes seeded on scaffold (MACI) | Histology (O’Driscoll and Pineda score), Mechanical testing and macroscopic evaluation | 32 |

| Frisbie et al. (2009) | Horse | 10/20 | CAIS | (1) Empty control. (2) PDS foam. (3) ACI | Histological and immunohistochemical examination. Gross arthroscopic examination | 52 |

| Marmotti et al. (2012) | Rabbit | 50/50 | Autologous cartilage fragments on membrane with and without fibrin glue | (1) Empty control. (2) Empty membrane. (3) Empty membrane with fibrin glue. | Histology (ICRS score and O’Driscoll scale) | 26 |

| Marmotti et al. (2013) | Goat | 18/36 | Autologous cartilage fragments on a HA scaffold + PRP and fibrin glue | (1) Empty control. (2) Empty HA scaffold + PRP and fibrin glue | Histology (ICRS score and O’Driscoll scale) | 52 |

| Bonasia et al. (2016) | Rabbit | 64/58 | Juvenile allogenic cartilage fragments | (1) Empty control. (2) Autologous cartilage fragments (3) Autologous cartilage combined with juvenile allogenic cartilage fragments | Histology (O’Driscoll scale), immunohistochemistry | 26 |

| Christensen et al. (2015) | Minipig | 16/43 | Autologous bone graft and cartilage chips | (1) Empty control. (2) Microfracture. (3) MACI. (4) cartilage chips alone | Histology (ICRS II score), MRI, CT | 26 |

| Christensen et al. (2016) | Minipig | 12/48 | Autologous bone graft and cartilage chips | Autologous bone graft alone | Histology (ICRS II score), histomorphometry, immunohistochemistry and CT | 52 |

| Christensen et al. (2017) | Minipig | 6/24 | Autologous cartilage chips in fibrin glue | Microfracture | Histology (ICRS II score), histomorphometry and immunohistochemistry | 26 |

| Dominguez-Perez et al. (2019) | Sheep | 6/12 | Autologous cartilage chips + PRP injection | NA | Histology (ICRS score), immunohistochemistry, transmission electron microscopy | 26 |

| Olesen et al. (2019) | Minipig | 6/24 | Autologous cartilage chips + PRP injection | Autologous cartilage chips alone | Histology (ICRS II score), histomorphometry and immunohistochemistry | 26 |

| Matshushita et al. (2019) | Rabbit | 56/76 | Juvenile allogenic cartilage fragments in atelocollagen scaffold | (1) MACI. (2) Empty defect. (3) Atelocollagen scaffold alone | Histology (Pineda score), macroscopic score, immunohistochemistry | 24 |

| Ao et al. (2019) | Minipig | 30/30 | Juvenile allogenic cartilage fragments | Autologous cartilage chips | Histology (ICRS II score), histomorphometry and immunohistochemistry | 26 |

MACI = matrix-induced autologous chondrocyte implantation; PGA = polyglycolic acid; PCL = polycaprolactone; PDS = polydioxanone; PRP = platelet-rich plasma; CAIS = cartilage autograft implantation system; HA = hyaluronic acid; ICRS = International Cartilage Research Society; MRI = magnetic resonance imaging; CT = computed tomography, NA = not applicable.

All studies were performed on the knee of the animal.

In 1983, Albrecht et al. 10 were the first to describe the use of autologous cartilage fragments for the repair of osteochondral defects in a rabbit model. The authors included 46 rabbits and treated 75 knee joints. Of the 75 knee joints, 36 were treated with minced cartilage fragments “moistured by thrombin solution and fibrinogen precipitate.” After up to 40 weeks, no hyaline cartilage was found in the control groups. In the minced cartilage group, hyaline cartilage was seen in 61% of defects, whereas the remaining 39% resembled the control groups.

In 2006, the next landmark study in particulated cartilage was published by Lu et al., 11 who described the use of autologous cartilage fragments in combination with a polyglycolic acid/polycaprolactone (PGA/PCL) scaffold in a goat model. They demonstrated superior outcome in both macroscopic appearance and microscopic score in terms of modified O’Driscoll after 6 months compared with empty defects or defects with a scaffold alone. Furthermore, the authors reported on migration of chondrocytes in the cartilage chips from the extracellular matrix.

In 2008, Lind et al. 24 demonstrated no significant microscopic (repair tissue fill, Pineda, O’Driscoll) or mechanical differences between chondral defects treated with autologous cartilage fragments in combination with a collagen scaffold, compared with ACI after 4 months in a goat model.

In 2009, Frisbie et al. 25 investigated autologous cartilage fragments in a horse model and compared it to empty defects, empty scaffold and ACI. They tested the CAIS where autologous cartilage fragments are combined with a polydioxanone (PDS) scaffold and fibrin glue and attached into the defect with PDS/PGA staples. They found superiority of autologous cartilage fragments compared with control groups and similar results as seen in ACI-treated defects. ACI and autologous cartilage fragments treated defects had significantly firmer tissue and higher O’Driscoll scores compared to controls.

In 2012, Marmotti et al. 26 conducted a study on autologous cartilage fragments in osteochondral defects in rabbits. In total, 50 rabbits were assigned to 5 different treatment groups: (1) cartilage fragments loaded onto a hyaluronic acid scaffold in combination with platelet-rich plasma (PRP) and fibrin glue or (2) without fibrin glue; (3) hyaluronic acid scaffold alone in combination with PRP and fibrin glue or (4) without fibrin glue; (5) empty defects. After 6 months the groups containing cartilage fragments (groups 1 and 2) showed significantly higher histological scores (ICRS and O’Driscoll) compared with remaining groups, with the group without addition of fibrin glue showing the highest scores.

In 2013, the same research group 27 conducted a similar study in osteochondral defects in goats with three groups investigated: (1) cartilage fragments loaded onto a hyaluronic acid scaffold in combination with platelet-rich fibrin matrix and fibrin glue; (2) hyaluronic acid scaffold, platelet-rich fibrin matrix, and fibrin glue alone; or (3) untreated. Group 1 showed superior outcome both mechanically and histologically with features of hyaline-like cartilage and presence of type II collagen after 12 months.

In 2016, Bonasia et al. 28 conducted a study on 58 rabbits. They investigated combined autologous adult cartilage combined with PJAC compared with autologous adult cartilage or PJAC alone and an empty control group. The combined group provided the best histological outcome after 6 months with significantly higher scores than the empty control group and the group treated with autologous adult cartilage.

Christensen et al.29-31 (authors of the present review) published studies in 2015, 2016, and 2017. In the first study, osteochondral defects made in the trochlea of minipigs were treated with a combination of autologous fragmented cartilage and autologous bone graft (autologous dual-tissue transplantation [ADTT]) compared with autologous bone graft alone. ADTT outperformed autologous bone graft alone in term of repair tissue morphology after 3 and 6 months. In the follow-up study in 2016, the same 2 groups were compared at 6 and 12 months. At 6 months, the ADTT-treated defects had significantly more hyaline cartilage than the defects treated with bone graft. The fraction of hyaline tissue in the ADTT group decreased at 12 months where no difference was seen between the groups. However, the ADTT-treated defects had significantly more fibrocartilaginous tissue and significantly less fibrous tissue compared with the defects treated with bone graft at 12 months. Furthermore, ADTT-treated defects scored higher than defects treated with bone graft on tissue and cell morphology at 12 months. In the third study from 2017, autologous cartilage fragments were used in chondral defects of minipigs and compared with control defects receiving microfracture. The defects were evaluated after 6 months. The defects treated with autologous cartilage fragments showed significantly more hyaline and less fibrous tissue, histological scores were significantly higher and there were twice as much collagen II staining compared with microfracture.

In 2019, Dominguez-Perez et al. 32 investigated chondral defects in sheep receiving treatment with autologous fragmented cartilage mixed with platelet-poor plasma with subsequent intra-articular injection of PRP. No control group was included but comparison was made between repair response after 1, 3 and 6 months. After 6 months repair, tissue showed features of mature hyaline cartilage both macro- and microscopically.

In 2019, Olesen et al. 33 compared the use of autologous fragmented cartilage in chondral defects of mini pigs with and without the addition of platelet rich plasma. The authors found approximately 20% hyaline cartilage, 50% fibrocartilage, and 22% fibrous tissue in both groups, and concluded that the addition of platelet rich plasma had no beneficial effect on repair.

In 2019, Matsushita et al. 34 studied 56 rabbits divided into 4 groups: (1) empty defect, (2) minced autologous cartilage embedded in an atelocollagen gel, (3) isolated chondrocytes in a atelocollagen gel (ACI), and (4) atelocollagen gel alone. In vitro, the minced cartilage increased the number of chondrocytes and the amount of matrix; however, in vivo both the mince cartilage group and the isolated chondrocyte group provided good cartilage repair compared to the control groups, and no difference was seen between minced cartilage and isolated chondrocytes.

In 2019, Ao et al. 35 compared PJAC with autologous cartilage chips in 30 Guizhou pigs. The pigs were euthanized at 1, 3, or 6 months and histomorphometry, immunohistochemistry, and semiquantitative scoring was performed. At 1 and 3 months, defects treated with autologous cartilage chips had more hyaline tissue and fibrocartilage, and less fibrous tissue. Furthermore, the autologous cartilage chips group scored higher in the semiquantitative score and had higher rates of immunohistochemical staining compared with PJAC. At 6 months, no difference was seen.

Clinical Studies

The literature search returned 16 clinical studies ( Table 2 ) describing 4 different techniques for clinical use:

Table 2.

Clinical Studies on Particulated Cartilage.

| Authors | Treatment/Location | Design | n | Lesion Size (cm2) | Outcome Measure | Follow-up (Months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cole et al. (2011) | CAIS/knee | RCT | 29 | 2.75 | ICRS | 24 |

| Bleazey et al. (2012) | PJAC/ankle | Retrospective cohort | 7 | 0.8 | Pain scale (1-10) and activity scale (1-10) | 6 |

| Coetzee et al. (2013) | PJAC/ankle | Retrospective cohort | 24 | 1.3 | AOFAS, FAAM, SF-12 | 16.2 |

| Tompkins et al. (2013) | PJAC/ankle | Retrospective cohort | 15 | 2.4 | KOOS, IKDC, VAS, Tegner, Kujala | 28.8 |

| Farr et al. (2014) | PJAC/knee | Prospective cohort | 25 | 2.7 | IKDC, KOOS, VAS, MRI | 24 |

| Buckwalter et al. (2014) | PJAC/patella | Retrospective cohort | 13 | 2.3 | KOOS, WOMAC | 8.2 |

| Grawe et al. (2017) | PJAC/patella | Retrospective cohort | 45 | 2.0 | MRI | 24 |

| Lanham et al. (2017) | PJAC/ankle | Retrospective cohort | 6 | 1.9 | AOFAS, FAAM, SF-12 | 25.7 |

| Saltzman et al. (2017) | PJAC/ankle | Prospective cohort | 6 | 1.65 | MRI, subjective and objective improvement | 13 |

| Wang et al. (2018) | PJAC/knee | Prospective cohort | 30 | 2.14 | KOOS, IKDC, MAS, MRI | 46 |

| Ryan et al. (2018) | PJAC/ankle | Prospective cohort | 34 | 1.07 | AOFAS, FAAM, VAS, SF-12 | 24 |

| Van Dyke et al. (2018) | PJAC/first metatarsal head | Retrospective cohort | 9 | 0.45 | AOFAS, VAS, FFI | 39.6 |

| Dekker et al. (2018) | PJAC/ankle | Retrospective cohort | 15 | 1.28 | AOFAS, FAOS | 34.6 |

| Christensen et al. (2015) | Autologous bone graft and cartilage chips/knee | Prospective cohort | 8 | 3.1 | KOOS, IKDC, Tegner, MRI, CT | 12 |

| Massen et al. (2019) | Autologous cartilage chips/knee | Prospective cohort | 27 | 3.1 | MRI, Numeric analog scale (pain) | 28.2 |

| Cugat et al. (2019) | Autologous cartilage chips in PPP/PRP clot/knee | Prospective cohort | 15 | 2.8 | MRI, VAS, WOMAC, IKDC, SF-12 | 15.9 |

RCT = randomized controlled trial; ICRS = International Cartilage Research Society; PJAC = particulated juvenile articular cartilage; AOFAS = American Orthopaedic Foot & Ankle Society; IKDC = International Knee Documentation Committee; KOOS = Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score; VAS = visual analogue scale; MRI = magnetic resonance imaging; CT = computed tomography; WOMAC = Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index; FAAM = Foot and Ankle Ability Measure; SF-12 = 12-item Short Form Health Survey; MAS = Modified Ashworth Scale; FFI = Foot Function Index; FAOS = Foot and Ankle Outcome Score; PPP = platelet-poor plasma; PRP = platelet-rich plasma.

The CAIS is a minced autologous cartilage embedded in a synthetic scaffold

DeNovo NT Natural Tissue Graft—particulated juvenile articular cartilage

Autologous cartilage chips—with and without concomitant bone grafting

Augmented autologous cartilage chips

The Cartilage Autograft Implantation System

In the CAIS technique, hyaline cartilage is arthroscopically harvested from a low load-bearing area of the knee. The cartilage biopsy is minced into 1- to 2-mm fragments using a specifically designed device. The device disperses the minced cartilage onto a biodegradable scaffold. The CAIS scaffold is a polymer foam consisting of 35% PCL and 65% PGA, reinforced with a PDS mesh. The cartilage fragments are secured to the scaffold using fibrin glue. Through a mini-arthrotomy, the defect is prepared by creating a clean bone bed with stable cartilage shoulders. The CAIS scaffold, cut to size and loaded with cartilage, is implanted and fixed with biodegradable staples. 25

The study to evaluate the safety of CAIS and to test whether CAIS improves quality of life by using standardized outcomes assessment tools is the only published CAIS study to date and represents the only randomized controlled trial on cartilage fragments. Twenty-nine patients were randomized to treatment with either microfracture or CAIS. SF-36, International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC), and Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) were reported at 6, 12, and 24 months. MRI was performed at baseline, and 6, 12, and 24 months postoperatively. Patient reported outcome measures showed an overall improvement in both groups. The IKDC and KOOS scores showed that improvements were maintained at 24 months. MRI revealed that defects treated with microfracture had higher rate of intralesional osteophyte formation. No differences were found in terms of fill of the graft bed, tissue integration, or presence of subchondral bone cysts. 12 A 300-patient randomized controlled trial comparing CAIS with microfracture was started in 2013. Unfortunately, the company behind the trial withdrew the study sponsorship and the trial was terminated. CAIS is not available for patients at this time.

DeNovo NT Natural Tissue Graft

The commercial allogeneic application of implantation of particulated juvenile cartilage is termed DeNovo NT (ISTO St. Louis, MO, USA; distributed by Zimmer, Warsaw, IN, USA). DeNovo NT is a “minimally manipulated human tissue allograft” and is regulated by the Food and Drug Administration as a 361 HCT/P product similar to fresh osteochondral allograft and bone-tendon-bone allograft—that is, it does not require a premarket approval process. Therefore, it has been clinically available since 2007 and by 2015, over 8,700 patients have been treated with DeNovo NT. 36 In PJAC, fresh cadaveric femoral condyles from human donors under the age of 13 are obtained. The articular cartilage in blister packs containing nutrients in 1 mm2 dice. Each blister pack covers a 2.5 cm2 defect. 13 The PJAC concept was presented by Dr. Farr at the International Cartilage Research Society Congress in 2009. 37 The first clinical data was published in 2010. Bonner et al. 38 treated a 36-year-old male patient with a symptomatic full-thickness patella cartilage defect. At the 2-year follow-up, the patient experienced significant clinical improvements in both pain and function. MRI showed near-complete resolution of preoperative bone edema and a defect filled with repair tissue. 38

In 2011, Farr et al. published preliminary results of 4 patients followed for 2 years. In 2014, the full study of 25 patients was published. 13 The patients were followed for 24 months. The authors found improvements in IKDC, KOOS, and VAS pain scores. Biopsies of the repair tissue from 8 patients demonstrated that the tissue was composed of a mixture of hyaline and fibrocartilage. 13

In 2013, Tompkins et al. 39 followed 16 patients with patella cartilage lesions treated with PJAC for 28 months. MRI evaluation demonstrated a defect filling of 89% and 73% of patients displaying “normal to nearly normal cartilage repair.” The mean IKDC score at final follow-up was 73 ± 17.6. 39

In 2014, Buckwalter et al. 40 reported on 17 cases treated with PJAC for patella cartilage lesions. The total KOOS score improved significantly from a mean of 58.4 ± 15.7 to 69.2 ± 18.6 after 8 months. 40

In 2017, Grawe et al. 41 performed an MRI analysis on 45 patients treated with PJAC. They found that 75% of patients had good to moderate filling of the cartilage defect at 24 months. The study also found a progressive maturation of the repair tissue over time. 41

In 2018, Wang et al. 42 investigated patella femoral cartilage lesions in 27 patients treated with PJAC and followed for an average of 3.84 years. The authors found significant improvements from pre- to postoperative mean IKDC (45.9 vs. 71.2) and KOOS-ADL (activities of daily living) (60.7 vs. 78.8). They did not, however, find a clinical correlation to MRI, which lacked the same improvements. 42

A number of case series for the application of PJAC in talar osteochondral lesions have been published. In a 2012 study by Bleazey et al., 43 7 patients followed for 6 months saw marked clinical improvements. The same was observed by Coetzee et al. 44 in 2013, where 23 patients were followed for 16 months and 78% had a good or excellent outcome and in a 2017 study by Saltzmann et al., 45 6 patients followed for 13 months saw subjective improvements in pain and function.

In 2017, Lanham et al. 46 compared 6 patients treated with bone marrow concentrate on a collagen scaffold with 6 patients treated with PJAC in a retrospective study. After 25 months, the authors found a significantly higher AOFAS (American Orthopaedic Foot & Ankle Society) score for the PJAC group (97.02) compared with the bone marrow concentrate group (71.33). 46

In 2018, Dekker et al. 47 followed 15 patients for 34 months. There was a 40% failure rate, and the predictors of poor outcome were found to be male gender and lesion size greater than 125 mm2. 47

Van Dyke et al. 48 used PJAC for first metatarsal osteochondral lesions in 2018. In 9 patients followed for an average of 3.3 years, the authors found a decrease in pain scores and an increase in the AOFAS score. Eight out of 9 patients were satisfied or very satisfied with the outcome. 48

In 2018, Ryan et al. 49 investigated if there was a difference in outcome when comparing open PJAC treatment with arthroscopic PJAC treatment. The study found no difference in patient-reported outcome and pain scores between techniques. They did find a significant improvement from baseline in both groups. 49

Autologous Cartilage Chips

An alternative to the PJAC treatment is ADTT. In ADTT, an osteochondral defect is prepared with a trephine. A bone biopsy is taken from the tibial tuberosity and implanted in the bony part of the defect. A cartilage biopsy is taken from the intercondylar notch, and the cartilage is fragmented using a No. 23 scalpel. The cartilage fragments are implanted into the defect and embedded in fibrin glue.

At this point, 1 short-term clinical study on ADTT has been published. In the 2015 study by Christensen et al. (authors of the current review), 8 patients were followed for 1 year. Evaluation consisted of MRI, CT, and clinical outcome scores. CT imaging showed more than 80% bone filling and MRI revealed significant improvements in the MOCART score, which improved from 22.5 to 52.5. Significant clinical improvements were found in the KOOS, IKDC and Tegner scores. 50 Five-year results are pending.

In 2019, Massen et al. 51 published a study on 27 patients suffering from full-thickness chondral defects treated with autologous cartilage chips embedded in fibrin glue (for patellar and trochlear defects a Chondro-Gide membrane was added). The patients experienced statistically significant improvements in the NAS (numerical analogue scale) pain score and in a subjective functional score. In addition, significant radiological improvements were observed in the MOCART (magnetic resonance observation of cartilage repair tissue) score 24 months postoperatively.

Augmented Autologous Cartilage Chips

In 2019, Cugat et al. 52 treated full-thickness chondral or osteochondral defects in 15 patients with autologous cartilage chips embedded in a clot consisting of PPP and PRP. At 15 months postoperatively, improvements were seen in the IKDC score, WOMAC score, Lysholm score, VAS score, and the radiological MOCART score.

Discussion

The efficacy of particulated cartilage for treatment of chondral and osteochondral defects have been demonstrated experimentally and clinically. While the initial study dates back to 1983, most studies have been published within the recent 8 years highlighting an increased interest in the technique. The increased interest has likely been motivated by the high cost of cell culturing in and the lack of a gold standard treatment for cartilage lesions.

The repair mechanism involved in cartilage regeneration when using cartilage chips is thought to be by chondrocyte outgrowth from the cartilage fragments, as demonstrated by Lu et al. 11 in 2006. Qiu et al. 14 found that the breakdown of extracellular matrix by collagenase helped the chondrocyte migration and Liu et al. found several matrix metalloproteinases upregulated in juvenile cartilage compared with adult cartilage. The authors have proposed that matrix metalloproteinases break down the extracellular matrix, thereby allowing the chondrocyte to create a migration path. 21

Only 2 studies, both experimental, have compared juvenile with autologous (adult) cartilage chips. Bonasia et al. 28 compared these in osteochondral defects in rabbits and found no difference in macroscopic appearance, histological scoring, and collagen type II staining. Ao et al. 35 compared juvenile cartilage chips with autologous cartilage chips in a porcine cartilage defect model. After 1 month, autologous cartilage chip treated defects had a higher percentage of hyaline cartilage and fibrocartilage, while the juvenile cartilage chip treated defects had a higher percentage of fibrous tissue. However, after 6 months no difference in tissue composition was found between the 2 treatment groups.

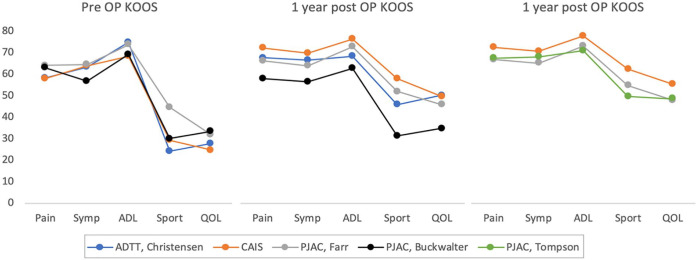

A similar pattern is seen in a clinical setting. While no clinical studies have compared juvenile cartilage with autologous cartilage, the results are quite comparable. 1 In Figure 1 , the KOOS scores from clinical studies on either juvenile cartilage chips or autologous (adult) cartilage chips have been compared. The limited amount of data does not allow for a statistical comparison, but it becomes apparent that the patient reported outcome is very similar, both preoperative, at 1 year and at 2 years. While juvenile cartilage chips hold a theoretical advantage over adult cartilage chips, further studies are needed to see if the theoretical benefit translates to a clinical setting.

Figure 1.

The preoperative, 1-year, and 2-year KOOS scores from 2 studies on autologous cartilage chips (ADTT, Christensen et al., 50 and CAIS 12 ), and 3 studies on juvenile cartilage (PJAC, Farr et al. 13 ; PJAC, Buckwalter 40 ; and PJAC, Thompson et al. 39 ). KOOS = Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score; ADTT = autologous dual-tissue transplantation; CAIS = cartilage autograft implantation system; PJAC = particulated juvenile allograft cartilage.

In general, the results of treatment with particulated cartilage have been encouraging, however poor results and failures have been reported when the treatment is applied to the talus. In the study by Saltzman et al., 45 3 of 6 patients had a persistent subchondral bone edema and uneven surface of the repair tissue after 14 months. Coetzee et al. 44 found that the clinical improvements diminished when treating defects larger than 150 mm2. Dekker et al. 47 found that 6 of 15 patients (40%) were clinical failures. The authors concluded that defects larger than 125 mm2 were prone to failure. 47 Tan et al. 53 performed 69 PJAC treatments for talar cartilage defects and reported on 4 clinical failures resulting in second-look arthroscopies. The authors found that 2 of the failures were due to lack of integration to surrounding tissue and 2 failures were due to bony and soft tissue impingement. They found no obvious surgical- or patient-related factors associated with poor outcome. Similar results have been found regarding microfracture treatment of talar defects highlighting the challenges of treating talar cartilage defects. Choi et al. 54 and Chuckpaiwong et al. 55 found significantly higher failure rates when treating talar defects larger than 150 mm2.

An arthroscopic technique for implantation of particulated cartilage has been described. After preparation of the defect, the joint is emptied of fluid. The surgeon can perform the procedure in an empty joint, or by using CO2 arthroscopy. The particulated cartilage is retrogradely loaded into an arthroscopic cannula and delivered to the defect using a trocar. The fibrin glue is injected into the defect filled with particulated cartilage. The arthroscopic technique has been used in talar defects, 56 and application in knee and hip cartilage defects is a possible future augmentation of the treatment.

This is a comprehensive literature review, that covers the subject of particulated cartilage in experimental and clinical studies. Despite the good experimental evidence for the concept of cartilage chip-based treatment, then there is still a lack of high-quality clinical trials to support clinical efficacy and long-term outcome.

Conclusion

Treatment with particulated cartilage, allogeneic or autologous, provides a low cost and effective treatment alternative to microfracture and ACI. Good clinical outcomes are best documented for knee lesion whereas high failure rates have been seen for talar lesions. The perspective of implanting the particulated chips arthroscopically and using particulated cartilage as an adjuvant treatment to other cartilage treatments only broadens the appeal.

Footnotes

Acknowledgments and Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Bjørn Borsøe Christensen  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3207-4536

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3207-4536

Kris Tvilum Chadwick Hede  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3309-5320

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3309-5320

Martin Lind  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7204-813X

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7204-813X

References

- 1. Christensen BB. Autologous tissue transplantations for osteochondral repair. Dan Med J. 2016;63(4):B5236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gou GH, Tseng FJ, Wang SH, Chen PJ, Shyu JF, Weng CF, et al. Autologous chondrocyte implantation versus microfracture in the knee: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Arthroscopy. 2020;36(1_suppl):289-303. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2019.06.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Solheim E, Hegna J, Inderhaug E. Long-term survival after microfracture and mosaicplasty for knee articular cartilage repair: a comparative study between two treatments cohorts. Cartilage. 2020;11(1_suppl):71-6. doi: 10.1177/1947603518783482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Saris DBF, Vanlauwe J, Victor J, Haspl M, Bohnsack M, Fortems Y, et al. Characterized chondrocyte implantation results in better structural repair when treating symptomatic cartilage defects of the knee in a randomized controlled trial versus microfracture. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36:235-46. doi: 10.1177/0363546507311095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Foldager CB, Farr J, Gomoll AH. Patients scheduled for chondrocyte implantation treatment with MACI have larger defects than those enrolled in clinical trials. Cartilage. 2016;7(2):140-8. doi: 10.1177/1947603515622659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Beretta R. Is there health inequity in Europe today? The “strange case” of the application of an European regulation to cartilage repair. J Heal Soc Sci. 2016;1(1_suppl):37-46. doi: 10.19204/2016/sthr6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Barber FA, Dockery WD. A computed tomography scan assessment of synthetic multiphase polymer scaffolds used for osteochondral defect repair. Arthroscopy. 2011;27(1_suppl):60-4. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2010.06.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Verdonk P, Dhollander a., Almqvist KF, Verdonk R, Victor J. Treatment of osteochondral lesions in the knee using a cell-free scaffold. Bone Joint J. 2015;97-B(3):318-23. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.97B3.34555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Christensen BB, Foldager CB, Jensen J, Jensen NC, Lind M. Poor osteochondral repair by a biomimetic collagen scaffold: 1- to 3-year clinical and radiological follow-up. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016;24(7):2380-7. doi: 10.1007/s00167-015-3538-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Albrecht F, Roessner A, Zimmermann E. Closure of osteochondral lesions using chondral fragments and fibrin adhesive. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1983;101(3):213-7. doi: 10.1007/BF00436773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lu Y, Dhanaraj S, Wang Z, Bradley DM, Bowman SM, Cole BJ, et al. Minced cartilage without cell culture serves as an effective intraoperative cell source for cartilage repair. J Orthop Res. 2006;24(6):1261-70. doi: 10.1002/jor.20135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cole BJ, Farr J, Winalski CS, Hosea T, Richmond J, Mandelbaum B, et al. Outcomes after a single-stage procedure for cell-based cartilage repair: a prospective clinical safety trial with 2-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(6):1170-9. doi: 10.1177/0363546511399382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Farr J, Tabet SK, Margerrison E, Cole BJ. Clinical, radiographic, and histological outcomes after cartilage repair with particulated juvenile articular cartilage: a 2-year prospective study. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42:1417-25. doi: 10.1177/0363546514528671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Qiu W, Murray MM, Shortkroff S, Lee CR, Martin SD, Spector M. Outgrowth of chondrocytes from human articular cartilage explants and expression of α-smooth muscle actin. Wound Repair Regen. 2000;8(5):383-91. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-475X.2000.00383.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sage A, Chang AA, Schumacher BL, Sah RL, Watson D. Cartilage outgrowth in fibrin scaffolds. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2009;23(5):486-91. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2009.23.3347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mitsuyama H, Healey R, Terkeltaub R, Coutts R, Amiel D. Calcification of human articular knee cartilage is primarily an effect of ageing rather than osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2007;15(5):559-65. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2006.10.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. DeGroot J, Verzijl N, Baan RA, Lafeber FP, Bijlsma JW, TeKoppelle JM. Age-related decrease in proteoglycan synthesis of human articular chondrocytes. Arhtirits Rheum. 1999;42(5):1003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bonasia DE, Martin JA, Marmotti A, Amendola RL, Buckwalter JA, Rossi R, et al. Cocultures of adult and juvenile chondrocytes compared with adult and juvenile chondral fragments: in vitro matrix production. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(11):2355-61. doi: 10.1177/0363546511417172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Namba RS, Meuli M, Sullivan KM, Le AX, Adzick NS. Spontaneous repair of superficial defects in articular cartilage in a fetal lamb model. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80(1_suppl):4-10. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199801000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Adkisson HD, 4th, Martin JA, Amendola RL, Milliman C, Mauch KA, Katwal AB, et al. The potential of human allogeneic juvenile chondrocytes for restoration of articular cartilage. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(7):1324-33. doi: 10.1177/0363546510361950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Liu H, Zhao Z, Clarke RB, Gao J, Garrett IR, Margerrison EE. Enhanced tissue regeneration potential of juvenile articular cartilage. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(11):2658-67. doi: 10.1177/0363546513502945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Marmotti A, Bonasia DE, Bruzzone M, Rossi R, Castoldi F, Collo G, et al. Human cartilage fragments in a composite scaffold for single-stage cartilage repair: an in vitro study of the chondrocyte migration and the influence of TGF-β1 and G-CSF. Knee Surg Sport Traumatol Arthrosc. 2013;21:1819-33. doi: 10.1007/s00167-012-2244-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bonasia DE, Marmotti A, Mattia S, Cosentino A, Spolaore S, Governale G, et al. The degree of chondral fragmentation affects extracellular matrix production in cartilage autograft implantation: an in vitro study. Arthroscopy. 2015;31(12):2335-41. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2015.06.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lind M, Larsen A. Equal cartilage repair response between autologous chondrocytes in a collagen scaffold and minced cartilage under a collagen scaffold: an in vivo study in goats. Connect Tissue Res. 2008;49:437-42. doi: 10.1080/03008200802325037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Frisbie DD, Lu Y, Kawcak CE, DiCarlo EF, Binette F, McIlwraith CW. In vivo evaluation of autologous cartilage fragment-loaded scaffolds implanted into equine articular defects and compared with autologous chondrocyte implantation. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(1 suppl):71S-80S. doi: 10.1177/0363546509348478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Marmotti A, Bruzzone M, Bonasia DE, Castoldi F, Rossi R, Piras L, et al. One-step osteochondral repair with cartilage fragments in a composite scaffold. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2012;20(12):2590-601. doi: 10.1007/s00167-012-1920-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Marmotti A, Bruzzone M, Bonasia DE, Castoldi F, Von Degerfeld MM, Bignardi C, et al. Autologous cartilage fragments in a composite scaffold for one stage osteochondral repair in a goat model. Eur Cells Mater. 2013;26:15-32. doi: 10.22203/eCM.v026a02 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bonasia DE, Martin JA, Marmotti A, Kurriger GL, Lehman AD, Rossi R, et al. The use of autologous adult, allogenic juvenile, and combined juvenile-adult cartilage fragments for the repair of chondral defects. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016;24(12):3988-96. doi: 10.1007/s00167-015-3536-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Christensen BB, Foldager CB, Olesen ML, Vingtoft L, Rölfing JH, Ringgaard S, et al. Experimental articular cartilage repair in the Göttingen minipig: the influence of multiple defects per knee. J Exp Orthop. 2015;2(1_suppl):13. doi: 10.1186/s40634-015-0031-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Christensen BB, Foldager CB, Olesen ML, Hede KC, Lind M. Implantation of autologous cartilage chips improves cartilage repair tissue quality in osteochondral defects. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(6):1597-604. doi: 10.1177/0363546516630977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Christensen BB, Olesen ML, Lind M, Foldager CB. Autologous cartilage chip transplantation improves repair tissue composition compared with marrow stimulation. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45(7):1490-6. doi: 10.1177/0363546517694617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Domínguez Pérez JM, Fernández-Sarmiento JA, Aguilar García D, Granados Machuca MDM, Morgaz Rodríguez J, Navarrete Calvo R, et al. Cartilage regeneration using a novel autologous growth factors-based matrix for full-thickness defects in sheep. Knee Surg Sport Traumatol Arthrosc. 2019;27(3):950-61. doi: 10.1007/s00167-018-5107-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Olesen ML, Christensen BB, Foldager CB, Hede KC, Jørgensen NL, Lind M. No effect of platelet-rich plasma injections as an adjuvant to autologous cartilage chips implantation for the treatment of chondral defects. Cartilage. doi: 10.1177/1947603519865318. Epub 2019 July 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Matsushita R, Nakasa T, Ishikawa M, Tsuyuguchi Y, Matsubara N, Miyaki S, et al. Repair of an osteochondral defect with minced cartilage embedded in atelocollagen gel: a rabbit model. Am J Sports Med. 2019;47(9):2216-24. doi: 10.1177/0363546519854372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ao Y, Li Z, You Q, Zhang C, Yang L, Duan X. The use of particulated juvenile allograft cartilage for the repair of porcine articular cartilage defects. Am J Sports Med. 2019;47(10):2308-15. doi: 10.1177/0363546519856346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Yanke AB, Tilton AK, Wetters NG, Merkow DB, Cole BJ. DeNovo NT particulated juvenile cartilage implant. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2015;23(3):125-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Farr J. DeNovo NT natural graft tissue. Paper presented at: 8th World Congress of the International Cartilage Repair Society; May 23-26, 2009; Miami, FL. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bonner K, Daner W, Yao JQ. 2-year postoperative evaluation of a patient with a symptomatic full-thickness patellar cartilage defect repaired with particulated juvenile cartilage tissue. J Knee Surg. 2010;23(2):109-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tompkins M, Hamann JC, Diduch DR, Bonner KF, Hart JM, Gwathmey FW, et al. Preliminary results of a novel single-stage cartilage restoration technique: particulated juvenile articular cartilage allograft for chondral defects of the patella. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(10):1661-70. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2013.05.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Buckwalter J, Bowman G, Albright J, Wolf B, Bollier M. Clinical outcomes of patellar chondral lesions treated with juvenile particulated cartilage allografts. Iowa Orthop J. 2014;34:44-9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Grawe B, Burge A, Nguyen J, Strickland S, Warren R, Rodeo S, et al. Cartilage regeneration in full-thickness patellar chondral defects treated with particulated juvenile articular allograft cartilage: an MRI analysis. Cartilage. 2017;8(4):374-83. doi: 10.1177/1947603517710308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wang T, Belkin NS, Burge AJ, Chang B, Pais M, Mahony G, et al. Patellofemoral cartilage lesions treated with particulated juvenile allograft cartilage: a prospective study with minimum 2-year clinical and magnetic resonance imaging outcomes. Arthroscopy. 2018;34(5):1498-505. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2017.11.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bleazey S, Brigido SA. Reconstruction of complex osteochondral lesions of the talus with cylindrical sponge allograft and particulate juvenile cartilage graft: provisional results with a short-term follow-up. Foot Ankle Spec. 2012;5(5):300-5. doi: 10.1177/1938640012457937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Coetzee JC, Giza E, Schon LC, Berlet GC, Neufeld S, Stone RM, et al. Treatment of osteochondral lesions of the talus with particulated juvenile cartilage. Foot Ankle Int. 2013;34:1205-11. doi: 10.1177/1071100713485739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Saltzman BM, Lin J, Lee S. Particulated juvenile articular cartilage allograft transplantation for osteochondral talar lesions. Cartilage. 2017;8(1_suppl):61-72. doi: 10.1177/1947603516671358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lanham NS, Carroll JJ, Cooper MT, Perumal V, Park JS. A comparison of outcomes of particulated juvenile articular cartilage and bone marrow aspirate concentrate for articular cartilage lesions of the talus. Foot Ankle Spec. 2017;10(4):315-21. doi: 10.1177/1938640016679697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Dekker TJ, Steele JR, Federer AE, Easley ME, Hamid KS, Adams SB. Efficacy of particulated juvenile cartilage allograft transplantation for osteochondral lesions of the talus. Foot Ankle Int. 2018;39(3):278-83. doi: 10.1177/1071100717745502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Van Dyke B, Berlet GC, Daigre JL, Hyer CF, Philbin TM. First metatarsal head osteochondral defect treatment with particulated juvenile cartilage allograft transplantation: a case series. Foot Ankle Int. 2018;39(2):236-41. doi: 10.1177/1071100717737482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ryan PM, Turner RC, Anderson CD, Groth AT. Comparative outcomes for the treatment of articular cartilage lesions in the ankle with a denovo nt natural tissue graft: open versus arthroscopic treatment. Orthop J Sport Med. 2018;6(12):2325967118812710. doi: 10.1177/2325967118812710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Christensen BB, Foldager CB, Jensen J, Lind M. Autologous dual-tissue transplantation for osteochondral repair: early clinical and radiological results. Cartilage. 2015;6(3):166-73. doi: 10.1177/1947603515580983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Massen FK, Inauen CR, Harder LP, Runer A, Preiss S, Salzmann GM. One-step autologous minced cartilage procedure for the treatment of knee joint chondral and osteochondral lesions: a series of 27 patients with 2-year follow-up. Orthop J Sport Med. 2019;7(6):2325967119853773. doi: 10.1177/2325967119853773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Cugat R, Alentorn-Geli E, Navarro J, Cuscó X, Steinbacher G, Seijas R, et al. A novel autologous-made matrix using hyaline cartilage chips and platelet-rich growth factors for the treatment of full-thickness cartilage or osteochondral defects: Preliminary results. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2020;28(1_suppl):2309499019887547. doi: 10.1177/2309499019887547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Tan EW, Finney FT, Maccario C, Talusan PG, Zhang Z, Schon LC. Histological and gross evaluation through second-look arthroscopy of osteochondral lesions of the talus after failed treatment with particulated juvenile cartilage: a case series. J Orthop Case Rep. 2018;8(2):69-73. doi: 10.13107/jocr.2250-0685.1056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Choi WJ, Park KK, Kim BS, Lee JW. Osteochondral lesion of the talus: is there a critical defect size for poor outcome? Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(10):1974-80. doi: 10.1177/0363546509335765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Chuckpaiwong B, Berkson EM, Theodore GH. Microfracture for osteochondral lesions of the ankle: outcome analysis and outcome predictors of 105 cases. Arthroscopy. 2008;24(1_suppl):106-12. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2007.07.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Adams SB, Jr, Demetracopoulos CA, Parekh SG, Easley ME, Robbins J. Arthroscopic particulated juvenile cartilage allograft transplantation for the treatment of osteochondral lesions of the talus. Arthrosc Tech. 2014;3(4):e533-e537. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2014.06.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]