Abstract

Objective

To systematically review the available clinical evidence regarding the safety and efficacy of knee intraosseous injections for the treatment of bone marrow lesions in patients affected by knee osteoarthritis.

Design

A literature search was carried out on PubMed, Embase, and Google Scholar databases in January 2020. The following inclusion criteria were adopted: (1) studies of any level of evidence, dealing with subchondral injection of bone substitute materials and/or biologic agents; (2) studies with minimum 5 patients treated; and (3) studies with at least 6 months’ follow-up evaluation. All relevant data concerning clinical outcomes, adverse events, and rate of conversion to arthroplasty were extracted.

Results

A total of 12 studies were identified: 7 dealt with calcium phosphate administration, 3 with platelet-rich plasma, and 2 with bone marrow concentrate injection. Only 2 studies were randomized controlled trials, whereas 6 studies were prospective and the remaining 4 were retrospective. Studies included a total of 459 patients treated with intraosseous injections. Overall, only a few patients experienced adverse events and clinical improvement was documented in the majority of trial. The lack of any comparative evaluation versus subchondral drilling alone is the main limitation of the available evidence.

Conclusions

Knee intraosseous injections are a minimally invasive and safe procedure to address subchondral bone damage in osteoarthritic patients. They are able to provide beneficial effects at short-term evaluation. More high-quality evidence is needed to confirm their potential and to identify the best product to adopt in clinical practice.

Keywords: osteoarthritis, bone marrow lesion, bone marrow edema, intraosseous injection, subchondroplasty, platelet-rich plasma (PRP), mesenchymal stem cells, bone marrow concentrate, tricalcium phosphate, bone substitutes

Introduction

A number of studies have highlighted that subchondral bone plays a key role in the initiation and progression of many knee joint pathologies. Bone marrow lesions (BMLs), detected at magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), are suggestive of the presence of subchondral bone damage, that can be linked to a number of different conditions:1,2 post-traumatic events, such as ligament injuries; primitive subchondral bone disorders, such as insufficiency fractures that could lead to spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee (SONK); degenerative diseases, such as OA; inflammatory condition, like rheumatoid arthritis; metabolic disorders, for example, osteoporosis; neurologic impairment, such as in the case of algodystrophy; vascular impairment, leading to avascular osteoneocrosis (AVN). Differential diagnosis could be extremely complex and should rely both on accurate clinical evaluation and imaging, 3 sometimes requiring seriated MRI assessments over time to proper target the therapeutic approach. In most cases, BMLs are reversible but sometimes they can “chronicize” with the onset of irreversible conditions, like SONK, 4 characterized by collapse of subchondral bone and gradual flattening of the articular surface.

With regard to knee OA, it is one of the most prevalent chronic health conditions among adults, leading to pain and functional disability.5,6 BMLs are common findings in the context of knee OA, and there are pathogenetic hypothesis suggesting that OA starts as an alteration in the subchondral bone, which then leads to the destruction of the overlying articular cartilage. Typical histopathological findings include microcracks, microedemas, microbleeding within the subchondral region, as well as subchondral bone cysts. 7 The sclerotic subchondral bone mineralization is lower than in healthy joints, leading to a lower stiffness and mechanical resistance, as demonstrated through mechanical tests.8,9 Furthermore, as cartilage has no innervation, the highly innervated subchondral bone may be one of the primary sources of pain. Under a clinical point of view, the presence of BMLs correlates with pain and joint deterioration, and larger BMLs areas are associated to symptoms’ worsening over time.10-13 Knee OA patients with pattern of BMLs show also a poor prognosis and have an accelerated progression to end-stage disease, with a highly predictable need for total knee arthroplasty (TKA)14-16: A study by Scher et al. 17 suggested that patients with BMLs of any pattern type were almost nine times as likely to progress to TKA compared with subjects without BMLs.

Although the incidence of OA is increasing and the issue of young and middle-aged active patients who prefer to postpone TKA is spreading, no fully effective conservative therapy has yet been established to restore the damaged cartilage. 18 Traditional injectable therapies have shown promising, but short-lasting results in patients affected by early or moderate OA.19-22 Biologic agents have also been introduced into clinical practice, and they are obviously attractive due to their potential to induce tissue healing and homeostatic regeneration without being deeply invasive.23,24 Since BMLs have shown to have a key role in the initiation and progression of the pathology, they represent a new possible target to be addressed for the treatment of OA.7,23,24

Intraosseous injections are a minimally invasive procedure performed to address chronic BMLs and improve subchondral bone quality without altering its physiological properties. They are carried out under fluoroscopic control to determine the injection site and the distribution of the injectable product in the subchondral region.12,25 Currently, there are different options to perform knee intraosseous injections:

(a) Calcium phosphate (CaP) bone substitute injection, also known as subchondroplasty, which exploits the good osteoconductive and osteoinductive properties of CaP ceramics to improve mineralization and promote local bone remodeling 26

(b) Platelet-rich plasma (PRP), which takes advantage of the several autologous growth factors (GFs) contained in platelets’ alpha-granules, which have been shown to promote osteogenic differentiation of resident mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs)23,24,27,28

(c) Bone marrow concentrate (BMC), which is a product rich in autologous MSCs harvested from the bone marrow. The intraosseous delivery of MSCs has been proven to be effective in bone fracture healing and in restoring the homeostasis of subchondral bone.29,30

The aim of the present article is to systematically review the available clinical evidence concerning the safety and efficacy of knee intraosseous injections. The primary outcome was the rate of conversion to arthroplasty, in order to understand whether this approach could play a role in delaying joint replacement.

Methods

A systematic review was performed on 3 medical electronic databases (PubMed, Embase, and Google Scholar) by 2 independent authors (FO and AP) on January 28, 2020. To achieve the maximum search strategy sensitivity we combined keywords with Boolean operators “OR” or “AND” for the literature terms “calcium phosphate,” “tricalcium,” “bone substitute,” “bony substitute,” “PRP,” “ACP,” “platelet-rich,” “Accufill,” “platelet derived,” “platelet concentrate,” “growth factor,” “stem cells,” “mesenchymal,” “adipose,” “BMC,” “bone marrow concentrate,” “SVF,” with the terms “subchondroplasty,” “subchondral injection,” “subchondral,” “intraosseous,” “bone cartilage interface,” and “interface.”

A total of 13,536 potential articles were identified through our database search.

The following inclusion criteria were adopted for study selection: clinical trials of any level of evidence, written in English, and reporting clinical results following knee intraosseous injections of bone substitutes or biologic agents (PRP or MSCs products), with a minimum number of 5 patients treated and a minimum follow-up period of 6 months. We excluded all articles coming from non-peer-reviewed journals, surveys, editorials, special topics, conference presentations, narrative reviews, articles where the access to the full text was blocked and case reports or mini case-series (<5 patients).

After title and abstract screening, 82 studies were assessed for eligibility. Full text was retrieved and after a deep and careful review 74 articles were excluded because not related to the knee joint, presented less than 5 cases or with an insufficient period of follow-up.

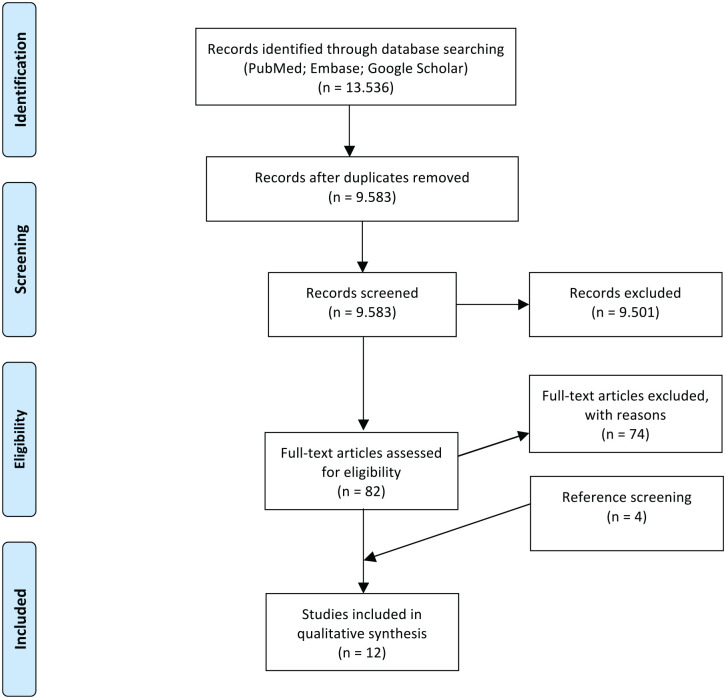

All the references of the retrieved articles were further reviewed for identification of potentially relevant studies and reassessed using the same inclusion and exclusion criteria stated above: 4 additional studies were included from the references. A PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) flowchart of the selection and screening process is provided in Figure 1 .

Figure 1.

PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) flowchart showing the studies’ selection process.

All data were extracted and reviewed from article texts, tables, and figures by 2 independent investigators (FO and AP). Discrepancies between the 2 reviewers were resolved by discussion and consensus. The final results were reviewed by the senior investigators (BDM and EK). The main outcome of the present systematic review was the rate of conversion to arthroplasty during follow-up evaluation. Demographics of patients, results in terms of pain evaluation and patients’ subjective reported outcomes were also collected.

Risk of bias and quality assessment of the included articles was done following the Coleman methodology score modified by Kon et al. 31 The assessment was independently performed by 2 authors (FO and AP). Any divergence was discussed with the senior investigators, who made the final judgment.

Results

Application Methods and Quality Assessment of the Available Literature

According to the aforementioned inclusion and exclusion criteria, we identified a total of 12 studies. Seven of the included articles involved the use of bone substitutes (i.e. subchondroplasty), 3 studies used the injection of PRP and other 2 involved injection of BMC. Studies quality was assessed by Coleman methodology modified by Kon et al. 31 Results of the quality assessment are detailed in Table 1 for each study. The average score was 40/100.

Table 1.

Quality Assessment of the Included Studies by Coleman Methodology Score Modified by Kon et al. 31 (Range 0-100).

| Study | Total | Study Size | Mean Follow-up | Other Procedures | Type of Study | Procedure Description | Postoperative Rehabilitation | MRI Outcome | Histological Outcome | Outcome Criteria | Outcome Assessment | Selection Process |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bonadio et al. RBO 2017 25 | 36 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 10 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 3 | 3 |

| Byrd et al. OJSM 2017 39 | 21 | 10 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Chua et al. JKS 2019 33 | 38 | 0 | 2 | 10 | 10 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 3 | 3 |

| Chatterjee et al. CORR 2015 38 | 31 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 3 | 8 |

| Cohen and Sharkey JKS 2016 14 | 41 | 10 | 2 | 10 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 3 | 6 |

| Davis et al. OJSM 2015 40 | 20 | 7 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 3 | 3 |

| Farr and Cohen OTSM 2013 34 | 34 | 7 | 2 | 0 | 10 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 3 | 0 |

| Su et al. CR 2018 32 | 52 | 4 | 2 | 10 | 15 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 3 | 8 |

| Sánchez et al. CAR 2019 36 | 48 | 4 | 2 | 10 | 10 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 9 | 3 |

| Sánchez et al. BMRI 2016 35 | 47 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 10 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 9 | 8 |

| Vad et al. Surgical Science 2016 37 | 48 | 0 | 2 | 10 | 10 | 5 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 5 | 3 | 3 |

| Hernigou et al. IO 2018 30 | 65 | 4 | 10 | 10 | 15 | 5 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 5 | 3 | 3 |

MRI = magnetic resonance imaging; IO = International Orthopedics; CR = Clinical Rheumatology; OTSM = Operative Techniques in Sports Medicine; OJSM = Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine; JKS = Journal of Knee Surgery; CAR = Cartilage; CORR = Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research; RBO = Revista Brasileira de Ortopedia; BMRI = BioMed Research International.

Patients’ Demographics

The studies included a total of 459 patients, with a mean age of 58 years (range 28-68 years) and an average follow-up of 23 months (range 6-144 months) as shown in Table 2 . Most of the studies had a mean follow-up around 14 months with the exception of Bonadio et al. 25 and Sánchez et al. 35 who evaluated their patients up to 6 months, while Hernigou et al. 30 had an average follow-up of 12 years. Eight out of 12 studies reported data on the grade of knee OA (Kellgren Lawrence or Ahlback scale) of the treated patients ( Table 2 ).

Table 2.

Patients’ Demographics and Relevant Characteristics of the Included Studies.

| Study | Level of Evidence | Product | Other Procedures | Number of Cases | Median Age (Years) | Mean Follow-up (Months) | Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | OA Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bonadio et al. RBO 2017 25 | IV | CaP Graftys HBS | None | 5 | 67.7 | 6 | N/A | 3 grade 1 KL, 2 grade 2 KL |

| Byrd et al. OJSM 2017 39 | IV | CaP (Zimmer Knee Creations) | None | 133 | 57 | 23.4 (range 14.6-32.1) | N/A | N/A |

| Chua et al. JK S 2019 33 | IV | CaP (Zimmer Knee Creations) | None | 12 | 54 | 12 | 28.3 | 10 grade 2 KL, 2 grade 3 KL |

| Chatterjee et al. CORR 2015 38 | IV | CaP (Zimmer Knee Creations) | 18/22 meniscectomy | 22 | 53.5 | 12 (range 6-24) | 29.7 | 2 grade 0 KL, 3 grade 1 KL, 9 grade 2 KL, 8 grade 3 KL |

| Cohen and Sharkey JKS 2016 14 | IV | CaP (Zimmer Knee Creations) | Arthroscopy | 66 | 55.9 | 24 | 30.1 | N/A |

| Davis et al. OJSM 2015 40 | IV | CaP (Zimmer Knee Creations) | None | 50 | 55 | 14.6 (range 12.9-25.1) | N/A | N/A |

| Farr and Cohen. OTSM 2013 34 | IV | CaP (Zimmer Knee Creations) | Arthroscopy | 59 | 55.6 | 14.7 | 30.3 | N/A |

| Su et al. CR 2018 32 | II | PRP | IA | 27 | 50.67 | 18 | 28 | 16 grade 2 KL, 11 grade 3 KL |

| Sánchez et al. Cartilage 2019 36 | III | PRP | IA | 30 | 63.4 | 12 | 31 | 27 grade 3 AL, 3 grade 4 AL |

| Sánchez et al. BMRI 2016 35 | IV | PRP | IA | 14 | 62 | 6 | 20-33 | 9 grade 3 AL, 5 grade 4 AL |

| Vad et al. Surgical Science 2016 37 | IV | MSC PeCaBoo delivery system | None | 10 | 63.5 | 14 | N/A | N/A |

| Hernigou et al. IO 2018 30 | II | MSC from BM | None | 30 | 28 | 144 | N/A | N/A |

MSC = mesenchymal stem cells; BM = bone marrow; IA = intra-articular; N/A = not available; IO = International Orthopaedics; JKS = Journal of Knee Surgery; CR = Clinical Rheumatology; OTSM = Operative Techniques in Sports Medicine; OJSM = Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine; CORR = Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research; RBO = Revista Brasileira de Ortopedia; BMRI = BioMed Research International; PRP = platelet-rich plasma; CaP = calcium phosphate; KL = Kellgren-Lawrence; AL = Ahlback scale; OA = osteoarthritis.

Concerning the study design, 2 studies were randomized controlled trials (RCTs),30,32 6 studies were prospective,25,33-37 whereas the remaining 4 were retrospective case series.14,38-40

Bone Substitutes

Six studies ( Table 3 ) investigated the outcome of CaP bone substitute Subchondroplasty (SCP; Zimmer Knee Creations, USA), whereas 1 study adopted the Graftys HBS (Graftys, France). 25 Three studies were prospective case series25,33,34 whereas 4 had a retrospective design.14,38-40

Table 3.

Clinical Outcomes of Studies Dealing with Calcium Phosphate Bone Substitutes.

| Study | Mean Follow-up (Months) | Results | Conversion to TKA | Complication | Need of Conservative Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bonadio et al. RBO 201725 | 6 | KOOS improved of 32.82 (p<0.05), VAS improved of 7.2 (p<0.05) | N/A | 1/5 had cement extravasation with local pain for 1 week | None |

| Byrd et al. OJSM 2017 39 | 23.4 (range 14.6-32.1) | VAS improved of 4.9 | 25% (32/128) | N/A | 35% in the short-term group required non-specified injections, 41% in the mid-term. |

| Chua et al. JKS 2019 33 | 12 | VAS improved of 5.4 (P < 0.001); KOOS improved of 34.7 (P < 0.001); WOMAC from 47.8 to 14.3 | N/A | 1/12 breakage of the cannula within the bone during removal | N/A |

| Chatterjee et al. CORR 2015 38 | 12 (range 6–24) | KOOS improved of 31.8; TLKSS improved of 29.5 | 45% (10/22) | None | 8 postoperative HA injection |

| Cohen and Sharkey JKS 2016 14 | 24 | VAS improved of 4.5; IKDC improved of 17.8; SF-12 improved of 6.9 | 30% (18/60) | 1/60 had postoperativee drainage at injection site, 1/60 had DVT | N/A |

| Davis et al. OJSM 2015 40 | 14.6 (range 12.9-25.1) | VAS improved of 4.7 | 8% (4/50) | 2 repeated episodes of knee swelling | 18/50 required additional HA and corticosteroid injection, 2 required serial aspiration |

| Farr and Cohen OTSM 2013 34 | 14.7 | VAS improved of 4.4; IKDC improved of 22.4; SF-12 improved of 6.9 at 6 months | 25.4% (15/59) | None | N/A |

TKA = total knee arthroplasty; VAS = visual analogue scale; IKDC = International Knee Documentation Committee; KOOS = Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score; WOMAC = Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index; TLKSS = Tegner-Lysholm Knee Scoring Score; CORR = Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research; RBO = Revista Brasileira de Ortopedia; OTSM = Operative Techniques in Sports Medicine; OJSM = Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine; JKS = Journal of Knee Surgery; N/A = not available; HA = hyaluronic acid; SF = Short Form Health Survey; DVT = deep venous thrombosis.

Arthroscopic control to assess the eventual extravasation of CaP into the joint was performed in 4 cases,14,33,34,38 whereas Bonadio et al. 25 used just fluoroscopy to this purpose, and the remaining 2 articles did not provide details.39,40 In 3 cases, cartilage procedures were concurrently performed.14,34,38

Clinical Findings

A statistically significant improvement in pain and function of the treated knees was reported in all but one trial, as detailed in Table 3 . One article showed poor results, with 10 patients out of 22 (45%) requiring conversion to arthroplasty within 1 year.

Looking at complications, only 6 patients out of 347 experienced adverse events. In one case, there was extra articular cement extravasation, which did not require further surgical treatment and was managed just by analgesic drugs in the postoperative phases. Cohen and Sharkey 14 reported 1 case of postoperative drainage, which required surgical irrigation debridement, and 1 episode of deep venous thrombosis. Davis et al. 40 reported 2 patients with repeated episodes of knee swelling, requiring multiple aspirations. Finally, Chua et al. 33 reported during removal the breakage of the injective cannula within the bone due to excessive knee manipulation.

With regard to the need of conservative retreatment, Byrd et al. 39 reported that 41% of patients sought for further intra-articular injections in the following 3 years, Davis et al. 40 reported 18 patients (36%) requiring hyaluronic acid (HA) or cortisone injection during the 24-month evaluation period, whereas in the study by Chatterjee et al., 38 8 patients required HA injection.

Looking at the TKA conversion rate, it ranged from 8% at mean 14 months’ follow-up 37 to 45% at mean 12 months’ follow-up. 38 Three studies14,34,39 showed similar percentage of conversion to arthroplasty (25%-30%) at comparable time intervals (approximately 24 months after treatment). In 2 studies, no data on TKA conversion rate are available.25,33

Platelet-Rich Plasma

Only 3 studies included in this review analyzed the results of knee intraosseous leukocyte-poor PRP injections.32,35,36 Sánchez et al. first performed a pilot trial 35 and then a comparative study 36 between 2 different treatment modalities: 1 subchondral injection of PRP followed by 2 intra-articular injections of the same PRP preparation 1 week apart versus 3 simple intra-articular injections. In the case of subchondral injections, 5 mL of PRP were applied both at the femoral and tibial bone-cartilage interface while 8 mL of PRP was used for intra-articular delivery.

Su et al. 32 performed a 3-arm RCT comparing (a) intraosseous injections of 2 mL of PRP (2 administration at 14-day interval), (b) intra-articular injections of 2 mL of PRP (2 administrations at 14-day intervals), and (c) intra-articular injections of HA (5 administration at 1-week interval).

Clinical Findings

Both the comparative trial by Sánchez et al. 36 and the RCT by Su et al. 32 revealed significantly superior results for the intraosseous administration of PRP compared with simple intra-articular delivery ( Table 4 ). Furthermore, the significant clinical differences were maintained up to the final evaluation (12 months in the case of Sánchez et al. 36 and 18 months in the study by Su et al. 32 ). Interestingly, no significant long-term difference was reported between intra-articular PRP and HA in the study by Su et al. 32

Table 4.

Clinical Outcomes of Studies Dealing with PRP Application.

| Study | Follow-up (Months) | Results | Conversion to TKA | Complications | Need of Conservative Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Su et al. CR 2018 32 | 18 | Significantly better results in intraosseous PRP group compared with pure intra-articular PRP and HA | N/A | 5 patients presented knee pain and swelling | N/A |

| Sánchez et al. Cartilage 2019 36 | 12 | Intraosseous PRP injection provided superior outcome compared with intra-articular PRP | 16.7% of intraosseous group received other “unspecified interventions” vs. 26.7% of intra-articular group | None | N/A |

| Sánchez et al. BMRI 2016 35 | 6 | VAS improved of 3.9; KOOS improved of 13.05 | 14.2% (2/14) | 1 exacerbation of knee pain after 3 months | N/A |

PRP = platelet-rich plasma; VAS = visual analogue scale; CR = Clinical Rheumatology; KOOS = Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score; WOMAC = Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index; N/A = not available; TKA = total knee arthroplasty; BMRI = BioMed Research International.

Considering the 3 studies, 5 minor adverse events (knee pain and swelling) were seen by Su et al., 32 whereas only knee swelling in 1 patient at 3 months from treatment was observed by Sánchez et al. 36

The rate of conversion to TKA has been mentioned by Sánchez et al. 36 : 2 patients out of 14 (14.2%) progressed to joint replacement within 6 months of follow-up. In the other article by Sánchez et al., 35 5 patients in the intraosseous group (16.7%) sought for other, not specified interventions compared to 8 patients (26.7%) in the intra-articular group.

Bone Marrow Concentrate

Only 2 trials investigated the subchondral injection of BMC: one of them is a prospective study, 37 whereas the other is an RCT comparing the outcomes of BMC injection versus TKA on the contralateral knee, in patients with previous long-term, high-dose corticosteroid therapy resulting in bilateral knee OA associated to osteonecrosis. 30

The therapeutic protocols were different: Vad et al. 37 harvested 5 cm3 of BMC from the ipsilateral tibia using the PeCaBoo system and then delivered it immediately at the bone-cartilage interface of the tibia and femur of the affected knee, under fluoroscopic guidance. Differently, Hernigou et al. 30 harvested 105 cm3 of BMC from the iliac crest plus an additional amount of bone marrow from the affected subchondral areas of the tibial plateau and femoral condyle, that was analysed to study the MSCs concentration in pathological areas and compare it to the “healthy” bone marrow obtained from the iliac crest. After concentration by centrifugation, 40 mL of BMC were injected into the femur and tibia, both medially and laterally.

Clinical and MRI Findings

With regard to the clinical outcomes, both studies reported improvement in patients’ reported scores. In particular, Hernigou et al. 30 found comparable clinical outcomes between the biologic treatment and TKA. Interestingly, the majority of patients (21 out of 30) were more satisfied with the status of the knee treated by MSCs application. Another remarkable finding was that MSCs concentration in the osteonecrotic areas of the knees was significantly lower compared with that of the iliac crest, thus confirming a biologic impairment in the subchondral osteonecrotic bone ( Table 5 ).

Table 5.

Clinical Outcomes of Studies Dealing with BMC Application.

| Study | Follow-up (Months) | Results | Conversion to TKA | Complications | Need of Conservative Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vad et al. Surgical Science 2016 37 | 14 | WOMAC improved of 22.9 (P < 0.01); NRS improved of 5.8 (P < 0.01), MRI cartilage volume increased of 14.1% | N/A | None | N/A |

| Hernigou et al. IO 2018 30 | 144 | Similar clinical outcomes among knees receiving BMC or

TKAPatients were significantly more satisfied with the

biologic treatment Cartilage volume increased of 4.2% at MRI in the BMC group |

10% (3/30) | 0% of blood transfusion in BMC vs 30% in TKA; DVT: 0% in BMC vs 15% in TKA at 6 months’ follow-up | None |

BMC = bone marrow concentrate; NRS = numerical rating scale; IO = International Orthopaedics; MSC = mesenchymal stem cells; WOMAC = Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index; N/A = not available; TKA = total knee arthroplasty; MRI = magnetic resonance imaging.

Even in terms of MRI outcomes, results were encouraging: Vad et al. 37 reported satisfactory restoration of the articular surface in 6 out of 10 patients with an average 23.5% increase of cartilage thickness, whereas Hernigou et al. 30 found a mean increase in thickness of 4.2% at their most recent follow-up (range 8-16 years). In addition, they documented a regression of BMLs in the femorotibial compartment of an average of 4.1 cm3 at 5 years’ follow-up, together with a significant decrease in the size of osteonecrosis by an average 40%. 30

Vad et al. 37 did not report any adverse events. Hernigou et al. 30 also reported no adverse events in knees treated by intraosseous injections, whereas a much higher complication and reoperation rate was reported in the arthroplasty group, as expected for the type of procedure.

Looking at conversion rate, 3 knees that received BMC in the study by Hernigou et al. 30 required TKA over the 12-year follow-up. 30

Discussion

The main finding of the present systematic review is the lack of high-quality clinical evidence concerning the efficacy of knee intraosseous injection, due to the paucity of RCTs and the modest overall methodology, often related to the limited number of patients included, their heterogeneity in terms of OA grade (from initial to severe OA), and the short-term evaluation, as testified by the low average scores assessed through the Coleman methodology modified by Kon et al. 31 Under a clinical point of view, it emerged that knee intraosseous injections, independently from the specific substance adopted, are safe and potentially able to provide symptomatic relief and functional recovery in osteoarthritic patients presenting BMLs.

Knee OA is a multifaceted disease, which involves all the intra- and extra-articular structures, thus representing a challenge in terms of treatment due to the impossibility of targeting all the tissues involved. Actually, under the name of OA there are different pathological entities characterized by different clinical presentations, ranging from inflammatory patterns to more mechanical features.41,42 There are several etiopathogenetic pathways currently investigated,43,44 and especially in recent years there has been a peculiar recognition of the role of subchondral bone: In fact it has been shown that patients presenting the so-called BMLs at MRI are usually more symptomatic and tend to have worse prognosis.16,17 Therefore, intraosseous injections were introduced with the aim of treating the pathologic subchondral bone tissue. The biologic rationale was to stimulate subchondral bone remodeling and healing in order to reduce symptoms and postpone more aggressive surgical procedures. The primary role of the subchondral treatment is therefore to delay joint replacement, especially in patients too young or in those affected by severe comorbidities that could increase the risk of postoperative complications.45,46

There are 2 different options for knee subchondral treatment: one is the “subchondroplasty” approach, consisting in the use of CaP bone substitutes, whereas the other is the “biologic” solution, which consists in the use of platelet-derived growth factors or concentrated MSCs, both of which demonstrated potential in promoting healing of different musculoskeletal tissues.47,48 The goal is to normalize the subchondral bone environment, although with very different mechanisms: in fact, the use of CaP ceramics, beyond promoting bone mineralization over time, is able to provide also immediate mechanical support in the subchondral region due to the physicochemical properties of these biomimetic ceramics: this could reduce micro-motion in the subchondral trabeculae thus accounting for a reduction in pain perceived by patients. 34 Differently, stimulation through growth factors or cell-based approaches activates different healing pathways in the subchondral bone, without immediate effects on the mechanical stability of the subchondral tissue. 23

The use of CaP is currently more represented in literature (7 studies vs 3 for PRP vs 2 for BMC), but no comparative analysis has yet been performed, and further randomized trials are necessary to understand whether a specific substance is able to provide better or longer lasting results. Furthermore, no clear indication can be drawn on the amount of substance that must be injected in the pathologic subchondral area, and whether there is any correlation with the size of BMLs observed at MRI.

Under a clinical point of view, the first relevant aspect coming from the analysis of literature is the overall safety of knee subchondral injections, which has been confirmed by all the trials available. Beyond the risks linked to surgical procedures in general, the most common complications are knee swelling and postoperative pain, which can be easily managed. The only real concern is the intra-articular leakage of the product when using CaP bone substitutes, which is more likely to happen in case of osteoporotic patients or when the cannula is placed too close to the articular surface. Overall, beneficial effects on symptoms and functional recovery have been documented at short term, with the majority of trials having performed evaluation in the range of 12 to 24 months after treatment. With regard to the survival rate, 1 trial on subchondroplasty 38 reported frankly disappointing results, with 45% of patients converted to TKA at short term, whereas the majority of the other subchondroplasty studies revealed a failure rate in the range of 25% to 30% up to 2 years, even if a significant amount of patients needing occasional retreatment (intra-articular injections of HA or corticosteroids) has been reported.39,40 Given the minimally invasive nature of knee intraosseous injections, a yearly failure rate of 10% to 15% could be still acceptable, provided that patients are clearly informed on the outcomes to expect following such treatment. At present moment, the only long-term evaluation has been performed by Hernigou et al. 30 on a very particular category of patients, that is, bilateral knee OA associated with osteonecrosis following long-term corticosteroid therapy: the low conversion to TKA rate (just 3 knees over 12 years) supports the efficacy of the procedure even in complex patients, but these findings should be interpreted with caution, since concurrent bilateral treatment is always affected by an assessment bias and the patients included in the trial are not those usually candidate to subchondral treatment in routine clinical practice.

Beyond differences in the mechanism of action, there are also “practical” differences which might have an impact on surgical choices: in fact, CaP bone substitutes are an “on-the shelf” products always available in the operating room, whereas autologous biologic products requires to be harvested, immediately prepared and then applied with inherent longer surgical time. Moreover, the use of biologic products, in particular MSCs, is often strictly regulated by health authorities, 49 and this led to the development of “minimal manipulation” strategies, 50 which allows immediate processing of MSCs in the operating room.

Looking at surgical technique, knee intraosseous injections are usually performed under fluoroscopic control, which could be a limiting factor since the optimal placement of the cannula within the BML is not guaranteed through fluoroscopy: the exact assessment of the extension and location of the lesion is done only by MRI and, therefore, X-ray guidance can results in a wrong positioning of the injecting device, especially in relatively small BMLs. To this purpose, novel software have been developed that are able to use preoperative MRI to calculate the optimal placement of the cannula, which can be controlled by intraoperative computed tomography.51,52 Alternatively, patient-specific MRI-based pointing devices could be realized to allow correct placement. 53 The use of these technologies is still not routine and should be evaluated against the obvious increase in costs.

Concerning the association of knee arthroscopy, it is recommended only when using CaP bone substitutes (subchondroplasty), to assess eventual intra-articular extravasation of the product, which could cause persistent joint inflammation. Arthroscopic approach also allows concurrent treatments such as cartilage procedures, articular lavage, or meniscal treatment, which could play a role in determining the outcome. On the other hand, arthroscopy may have a negative impact on the joint environment and increase the risk of infection: therefore, arthroscopy is not suggested when using biologic products, also because PRP and BMC have the advantage of being injected both intraosseously and intra-articularly, so arthroscopic fluid could dilute them and reduce their potential. On this specific aspect, it is relevant to note that 2 studies on PRP proved that subchondral injections significantly improve the outcomes compared with pure intra-articular delivery, thus confirming the necessity of addressing specifically the subchondral bone damage.32,36,54

All the aforementioned encouraging findings should be always carefully considered in the light of the many limitations of the current literature, in particular the paucity of studies available, mostly case series, the small number of patients included (just 4 trials had more than 50 patients), the short follow-up, and the lack of serial MRI evaluations to understand the healing potential associated to subchondral treatment. Anyway, the most relevant flaw emerged is the lack of randomized trials comparing knee intraosseous injections with subchondral “decompression” alone. Mechanical stimulation through a single or multiple subchondral perforations has been originally employed for the treatment of femoral head osteonecrosis with the aim of reducing intraosseous pressure, restore normal vascular flow and ultimately promote subchondral bone remodeling.55,56 Therefore, knee subchondral perforation, which always takes place before injecting any substance, has a beneficial effect per se, that needs to be properly compared with that of the “augmentation” through the injection of CaP or biologics products.

Beyond the limitations of the literature, we need also to consider some potential barriers to the spread of subchondral treatment in routine practice: in particular, the high costs of the products and the surgical kits necessary to perform the procedure, also considering the lack of studies investigating the cost-effectiveness of this novel surgical approach. This is particularly true when it comes to biologic products, a field where there is a large inter-product variability and standardization is far from being reached.57-59

To conclude, knee intraosseous injections can be regarded as a minimally invasive and safe procedure to address subchondral bone damage, with the goal of delaying joint replacement or offering a salvage option to those not eligible for arthroplasty. Current evidence does not allow to identify the superiority of a specific product over the others; looking at the data on the rate of conversion to arthroplasty (25%-30% on average up to two years’ evaluation), patient counselling is fundamental to avoid unrealistic expectations after subchondral procedures, and further studies are needed to answer fundamental questions: the first one is whether subchondral injections (of any substance) in the knee provide better outcome than subchondral decompression alone. Then, it should be elucidated if any difference exists among the various products available in terms of durability of results and, last, the best therapeutic protocols to apply.

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: This investigation was performed at the Humanitas Clinical and Research Center, IRCCS, Milan, Italy.

Acknowledgment and Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Berardo Di Matteo  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9807-0271

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9807-0271

Francesco Onorato  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2738-0360

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2738-0360

References

- 1. Kon E, Ronga M, Filardo G, Farr J, Madry H, Milano G, et al. Bone marrow lesions and subchondral bone pathology of the knee. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016;24(6):1797-814. doi: 10.1007/s00167-016-4113-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Manara M, Varenna M. A clinical overview of bone marrow edema. Reumatismo. 2014;66(2):184-96. doi: 10.4081/reumatismo.2014.790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gorbachova T, Melenevsky Y, Cohen M, Cerniglia BW. Osteochondral lesions of the knee: differentiating the most common entities at MRI. Radiographics. 2018;38(5):1478-95. doi: 10.1148/rg.2018180044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sibilska A, Góralczyk A, Hermanowicz K, Malinowski K. Spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee: what do we know so far? A literature review. Int Orthop. 2020;44(6):1063-9. doi: 10.1007/s00264-020-04536-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Johnson VL, Hunter DJ. The epidemiology of osteoarthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2014;28(1_suppl):5-15. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2014.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nguyen US, Zhang Y, Zhu Y, Niu J, Zhang B, Felson DT. Increasing prevalence of knee pain and symptomatic knee osteoarthritis: survey and cohort data. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(11):725-32. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-11-201112060-00004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Madry H, van Dijk CN, Mueller-Gerbl M. The basic science of the subchondral bone. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2010;18(4):419-33. doi: 10.1007/s00167-010-1054-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Li B, Aspden RM. Mechanical and material properties of the subchondral bone plate from the femoral head of patients with osteoarthritis or osteoporosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1997;56(4)247-54. doi: 10.1136/ard.56.4.247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Li G, Yin J, Gao J, Cheng TS, Pavlos NJ, Zhang C, et al. Subchondral bone in osteoarthritis: insight into risk factors and microstructural changes. Arthritis Res Ther. 2013;15(6):223. doi: 10.1186/ar4405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Felson DT, Niu J, Guermazi A, Roemer F, Aliabadi P, Clancy M, et al. Correlation of the development of knee pain with enlarging bone marrow lesions on magnetic resonance imaging. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(9):2986-92. doi: 10.1002/art.22851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Filardo G, Kon E, Tentoni F, Andriolo L, Di Martino A, Busacca M, et al. Anterior cruciate ligament injury: post-traumatic bone marrow oedema correlates with long-term prognosis. Int Orthop. 2016;40(1_suppl):183-90. doi: 10.1007/s00264-015-2672-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Davies-Tuck ML, Wluka AE, Forbes A, Wang Y, English DR, Giles GG, et al. Development of bone marrow lesions is associated with adverse effects on knee cartilage while resolution is associated with improvement—a potential target for prevention of knee osteoarthritis: a longitudinal study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12(1_suppl):R10. doi: 10.1186/ar2911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yusuf E, Kortekaas MC, Watt I, Huizinga TW, Kloppenburg M. Do knee abnormalities visualised on MRI explain knee pain in knee osteoarthritis? A systematic review. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(1_suppl):60-7. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.131904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cohen SB, Sharkey PF. Subchondroplasty for treating bone marrow lesions. J Knee Surg. 2016;29(7):555-63. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1568988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nielsen FK, Egund N, Jørgensen A, Jurik AG. Risk factors for joint replacement in knee osteoarthritis; a 15-year follow-up study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2017;18(1_suppl):510. doi: 10.1186/s12891-017-1871-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tanamas SK, Wluka AE, Pelletier JP, Pelletier JM, Abram F, Berry PA, et al. Bone marrow lesions in people with knee osteoarthritis predict progression of disease and joint replacement: a longitudinal study. Rheumatol (Oxford, England). 2010;49(12):2413-9. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keq286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Scher C, Craig J, Nelson F. Bone marrow edema in the knee in osteoarthrosis and association with total knee arthroplasty within a three-year follow-up. Skeletal Radiol. 2008;37(7):609-17. doi: 10.1007/s00256-008-0504-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Richards MM, Maxwell JS, Weng L, Angelos MG, Golzarian J. Intra-articular treatment of knee osteoarthritis: from anti-inflammatories to products of regenerative medicine. Phys Sportsmed. 2016;44(2):101-8. doi: 10.1080/00913847.2016.1168272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chahla J, Piuzzi NS, Mitchell JJ, Dean CS, Pascual-Garrido C, LaPrade RF, et al. Intra-articular cellular therapy for osteoarthritis and focal cartilage defects of the knee: a systematic review of the literature and study quality analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2016;98:1511-21. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.15.01495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rodriguez-Fontan F, Piuzzi NS, Kraeutler MJ, Pascual-Garrido C. Early clinical outcomes of intra-articular injections of bone marrow aspirate concentrate for the treatment of early osteoarthritis of the hip and knee: a cohort study. PM R. 2018;10(12):1353-9. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2018.05.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Emadedin M, Labibzadeh N, Liastani MG, Karimi A, Jaroughi N, Bolurieh T, et al. Intra-articular implantation of autologous bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells to treat knee osteoarthritis: a randomized, triple-blind, placebo-controlled phase 1/2 clinical trial. Cytotherapy. 2018;20(10):1238-46. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2018.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lopa S, Colombini A, Moretti M, de Girolamo L. Injective mesenchymal stem cell-based treatments for knee osteoarthritis: from mechanisms of action to current clinical evidences. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2019;27(6):2003-20. doi: 10.1007/s00167-018-5118-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Roffi A, Di Matteo B, Krishnakumar GS, Kon E, Filardo G. Platelet-rich plasma for the treatment of bone defects: from pre-clinical rational to evidence in the clinical practice. A systematic review. Int Orthop. 2017;41(2):221-37. doi: 10.1007/s00264-016-3342-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rodeo SA. Cell therapy in orthopaedics: where are we in 2019? Bone Joint J. 2019;101-B(4):361-4. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.101B4.BJJ-2019-0013.R1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bonadio MB, Giglio PN, Helito CP, Pécora JR, Camanho GL, Demange MK. Subchondroplasty for treating bone marrow lesions in the knee—initial experience. Rev Bras Ortop. 2017;52(3):325-30. doi: 10.1016/j.rboe.2017.04.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Astur D, Vasconcelos de Freitas E, Cabral P, Morais C, Pavei B, Kaleka C, et al. Evaluation and management of subchondral calcium phosphate injection technique to treat bone marrow lesion. Cartilage. 2019;10(4):395-401. doi: 10.1177/1947603518770249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Xie Y, Chen M, Chen Y, Xu Y, Sun Y, Liang J, et al. Effects of PRP and LyPRP on osteogenic differentiation of MSCs. J Biomed Mater Res. 2019;108(1_suppl):116-26. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.36797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zou J, Yuan C, Wu C, Cao C, Yang H. The effects of platelet-rich plasma on the osteogenic induction of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Connect Tissue Res. 2014;55(4):304-9. doi: 10.3109/03008207.2014.930140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dray A, Read SJ. Arthritis and pain. Future targets to control osteoarthritis pain. Arthritis Res Ther. 2007;9(3):212. doi: 10.1186/ar2178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hernigou P, Auregan JC, Dubory A, Flouzat-Lachaniette CH, Chevallier N, Rouard H. Subchondral stem cell therapy versus contralateral total knee arthroplasty for osteoarthritis following secondary osteonecrosis of the knee. Int Orthop. 2018;42(11):2563-71. doi: 10.1007/s00264-018-3916-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kon E, Verdonk P, Condello V, Delcogliano M, Dhollander A, Filardo G, et al. Matrix-assisted autologous chondrocyte transplantation for the repair of cartilage defects of the knee: systematic clinical data review and study quality analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(Suppl 1):156S-166S. doi: 10.1177/0363546509351649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Su K, Bai Y, Wang J, Zhang H, Liu H, Ma S. Comparison of hyaluronic acid and PRP intra-articular injection with combined intra-articular and intraosseous PRP injections to treat patients with knee osteoarthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2018;37(5):1341-50. doi: 10.1007/s10067-018-3985-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chua K, Yida J, Kang B, Ding F, Ng J, Pang HN, et al. Subchondroplasty for bone marrow lesions in the arthritic knee results in pain relief and improvement in function. J Knee Surg. Published online November 21, 2019. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1700568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Farr J, Cohen SB. Expanding applications of the subchondroplasty procedure for the treatment of bone marrow lesions observed on magnetic resonance imaging. Oper Tech Sports Med. 2013;21(2):138-43. doi: 10.1053/j.otsm.2013.03.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sánchez M, Delgado D, Sánchez P, Muiños-López E, Paiva B, Granero-Moltó F, et al. Combination of intra-articular and intraosseous injections of platelet rich plasma for severe knee osteoarthritis: a pilot study. BioMed Res Int. 2016;2016:4868613. doi: 10.1155/2016/4868613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sánchez M, Delgado D, Pompei O. Treating severe knee osteoarthritis with combination of intra-osseous and intra-articular infiltrations of platelet-rich plasma: an observational study. Cartilage. 2019;10(2):245-53. doi: 10.1177/1947603518756462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Vad V, Barve R, Linnell E, Harrison J. Knee osteoarthritis treated with percutaneous chondral-bone interface optimization: a pilot trial. Surg Sci. 2016;7(1_suppl):1-12. doi: 10.4236/ss.2016.71001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chatterjee D, McGee A, Strauss E, Youm T, Jazrawi L. Subchondral calcium phosphate is ineffective for bone marrow edema lesions in adults with advanced osteoarthritis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(7):2334-42. doi: 10.1007/s11999-015-4311-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Byrd JM, Akhavan S, Frank DA. Mid-term outcomes of the subchondroplasty procedure for patients with osteoarthritis and bone marrow edema. Orthop J Sports Med. 2017;5(7 Suppl 6):2325967117S0029. doi: 10.1177/2325967117S00291 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Davis AT, Byrd JM, Zenner JA, Frank DA, DeMeo PJ, Akhavan S. Short-term outcomes of the subchondroplasty procedure for the treatment of bone marrow edema lesions in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Orthop J Sports Med. 2015;3(7 Suppl 2):2325967115S0012. doi: 10.1177/2325967115S00125 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Veronesi F, Vandenbulcke F, Ashmore K. Meniscectomy-induced osteoarthritis in the sheep model for the investigation of therapeutic strategies: a systematic review. Int Orthop. 2020;44:779-93. doi: 10.1007/s00264-020-04493-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Di Matteo B, Perdisa F, Gostynska N, Kon E, Filardo G, Marcacci M. Meniscal scaffolds—preclinical evidence to support their use: a systematic review. Open Orthop J. 2015;9:143-56. doi: 10.2174/1874325001509010143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. De Santis M, Di Matteo B, Chisari E. The role of Wnt pathway in the pathogenesis of OA and its potential therapeutic implications in the field of regenerative medicine. BioMed Res Int. 2018;2018:7402947. doi: 10.1155/2018/7402947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sokolove J, Lepus CM. Role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis: latest findings and interpretations. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2013;5(2):77-94. doi: 10.1177/1759720X12467868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Scardino M, Martorelli F, D’Amato T. Use of a fibrin sealant within a blood-saving protocol in patients undergoing revision hip arthroplasty: effects on post-operative blood transfusion and healthcare-related cost analysis. Int Orthop. 2019;43(12):2707-14. doi: 10.1007/s00264-019-04291-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sultan AA, Mahmood B, Samuel LT. Patients with a history of treated septic arthritis are at high risk of periprosthetic joint infection after total joint arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2019;477(7):1605-12. doi: 10.1097/CORR.0000000000000688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Di Matteo B, Loibl M, Andriolo L. Biologic agents for anterior cruciate ligament healing: a systematic review. World J Orthop. 2016;7(9):592-603. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v7.i9.592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kopka M, Bradley JP. The use of biologic agents in athletes with knee injuries. J Knee Surg. 2016;29(5):379-86. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1599135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Di Matteo B, Kon E. Editorial commentary: biologic products for cartilage regeneration-time to redefine the rules of the game? Arthroscopy. 2019;35(1_suppl):260-1. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2018.07.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Di Matteo B, Vandenbulcke F, Vitale ND, Iacono F, Ashmore K, Marcacci M, et al. Minimally manipulated mesenchymal stem cells for the treatment of knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review of clinical evidence. Stem Cells Int. 2019;2019:1735242. doi: 10.1155/2019/1735242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Hoffmann R, Thomas C, Rempp H, Schmidt D, Pereira PL, Claussen CD, et al. Performing MR-guided biopsies in clinical routine: factors that influence accuracy and procedure time. Eur Radiol. 2011;22(3):663-71. doi: 10.1007/s00330-011-2297-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Weiss CR, Nour SG, Lewin JS. MR-guided biopsy: a review of current techniques and applications. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2008;27(2):311-25. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Gutmann S, Winkler D, Müller M, Möbius R, Fischer JP, Böttcher P, et al. Accuracy of a magnetic resonance imaging-based 3D printed stereotactic brain biopsy device in dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 2020;34(2):844-51. doi: 10.1111/jvim.15739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Di Martino A, Di Matteo B, Papio T. Platelet-rich plasma versus hyaluronic acid injections for the treatment of knee osteoarthritis: results at 5 years of a double-blind, randomized controlled trial. Am J Sports Med. 2019;47(2):347-54. doi: 10.1177/0363546518814532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lieberman JR. Core decompression for osteonecrosis of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;(418):29-33. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200401000-0000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Mont MA, Carbone JJ, Fairbank AC. Core decompression versus nonoperative management for osteonecrosis of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;(324):169-78. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199603000-00020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Di Matteo B, Filardo G, Lo Presti M, Kon E, Marcacci M. Chronic anti-platelet therapy: a contraindication for platelet-rich plasma intra-articular injections? Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2014;18(1 Suppl):55-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Perdisa F, Filardo G, Di Matteo B, Marcacci M, Kon E. Platelet rich plasma: a valid augmentation for cartilage scaffolds? A systematic review. Histol Histopathol. 2014;29(7):805-14. doi: 10.14670/HH-29.805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. O’Connell B, Wragg NM, Wilson SL. The use of PRP injections in the management of knee osteoarthritis. Cell Tissue Res. 2019;376(2):143-52. doi: 10.1007/s00441-019-02996-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]