Introduction

Brazil, the largest Latin American country, ranks fifth in the world by both geographic area and population (209.469 million inhabitants in 2018). The annual rate of population growth is 0.82% (1). The population has a mixed ethnicity, with 44% of them self-declared as of white skin color; 10.5% of the inhabitants are over 65 years old, and life expectancy at birth is 75.5 years (1). Although the country has experienced great social and economic development over the last decades, notable inequalities are still present. The southern and southeastern regions concentrate most of the economic resources and industrial, technological, and health care capabilities. The gross national income per capita was US$9140 in 2018. The total expenditure on health per capita in 2016 was US$796, corresponding to 9% of the gross national income (2).

In 1974, the Brazilian Public Health System recognized chronic dialysis as a treatment for ESKD, initiating the reimbursement of the procedure. The implementation of a unified public health system in 1993 was a cornerstone in the assertion of the creation of a country-wide permanent program to integrally finance the chronic maintenance dialysis treatment of all patients with ESKD (3). From then on, the program size and the numbers of patients and clinics have progressively increased. Over the years, Brazil has been ranked third in the world in the number of patients undergoing dialysis.

The Brazilian Society of Nephrology has been annually monitoring the epidemiologic data from these patients since 1999 through a national dialysis registry (4–6). In the last surveys, the response rate of the clinics was around 40%, and therefore, caution should be exercised regarding data interpretation. Although there is universal chronic dialysis coverage in Brazil, access to care is not uniform. Some patients with renal failure, particularly the oldest ones (7), those of lower social class, or those living far from health care centers with dialysis facilities (particularly in the north and northeast regions of the country), may not receive timely treatment. There is still considerable room for improvement regarding the integration of primary care facilities with more advanced health care centers.

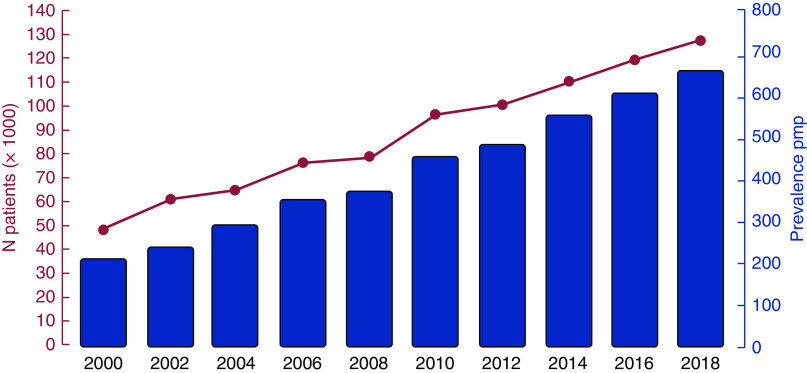

In July 2018, there were 133,464 patients on maintenance dialysis, corresponding to an average annual increase of 6.6% in the last 5 years (5,6) (Figure 1). As for the therapy modality, 92.3% were on hemodialysis (HD), and 7.7% were on peritoneal dialysis (PD). Overall, 89.9% were on conventional in-center dialysis (4 hours three times per week), 2.4% were on in-center more frequent dialysis (four or more times per week), and 0.1% were on home HD (Table 1). Home dialysis is restricted to automated PD because the home HD activity is incipient in the country. Most patients (64.5%) were in the 20- to 64-years-old age group, 1.2% were <20 years old, and 34.3% were ≥65 years old. Fifty-eight percent of the patients were men. The major reported primary renal diseases were hypertension at 33.9%, diabetic nephropathy at 30.8%, GN at 9.1%, and polycystic kidney disease at 4%. The proportion of patients on HD using an arteriovenous fistula was 73.8%, the proportion of patients on HD using a central venous catheter was 23.6%, and the proportion of patients on HD using a graft was 2.6%. At the start of the dialysis program, up to 65% of patients used a central venous catheter as the vascular access (8).

Figure 1.

Number of patients and prevalence rates of dialysis treatment in Brazil by year from 2000 to 2018. pmp, per million population.

Table 1.

Percentage of patients according to dialysis modality and type of financing, 2018

| Dialysis Modality | Public System, % | Private Insurance, % | Total, % |

| Conventional HD | 91.7 | 82.7 | 89.9 |

| Daily HD (≥4 times per week) | 0.4 | 10.6 | 2.4 |

| Home HD | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| CAPD | 2.1 | 1.1 | 1.9 |

| APD | 5.7 | 5.9 | 5.7 |

| IPD | 0.1 | 0 | 0.1 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 |

HD, hemodialysis; CAPD, continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis; APD, automated peritoneal dialysis; IPD, intermittent peritoneal dialysis.

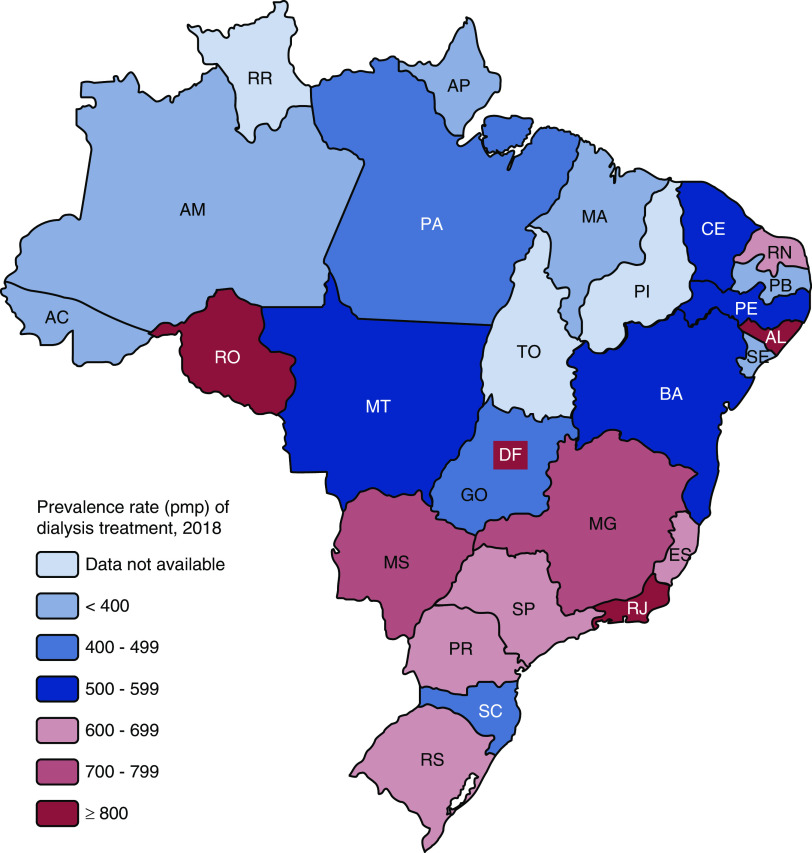

The overall estimated prevalence rate of dialysis treatment was 640 patients per million population (pmp), ranging from 448 pmp in the north to 738 pmp in the southeast region (Figures 1 and 2). The prevalence rate tended to increase in all regions over the years, from 499 pmp in 2013 to 640 pmp in 2018 (28.3%); this is an average annual increase of 28.2 pmp. Most patients were on dialysis in the states of São Paulo, Minas Gerais, and Rio de Janeiro (southeastern region) (Figure 2). The overall prevalence of RRT, including subjects on dialysis or with a functioning renal graft, was 876 pmp in 2018, an estimate near to that of several Western European countries (9).

Figure 2.

Geographic variation in the prevalence rate of dialysis treatment (per million population) by state in Brazil in 2018. AC, Acre; AL, Alagoas; AP, Amapá; AM, Amazonas; BA, Bahia; CE, Ceará; DF, Distrito Federal; ES, Espírito Santo; GO, Goiás; MA, Maranhão; MG, Minas Gerais; MS, Mato Grosso do Sul; MT, Mato Grosso; PA, Pará; PB, Paraíba; PE, Pernambuco; PI, Piauí; PR, Paraná; RJ, Rio de Janeiro; RN, Rio Grande do Norte; RO, Rondônia; RR, Roraima; RS, Rio Grande do Sul; SC, Santa Catarina; SE, Sergipe; SP, São Paulo; TO, Tocantins.

The number of patients starting dialysis in 2018 was estimated at 40,307, yielding an incidence rate of 194 pmp (ranging from 142 in the north to 221 in the southeast). The incidence rate has increased in the past years. Forty percent of the incident patients had diabetic nephropathy. As for the prevalent patients, the last result of hemoglobin level was <10 g/dl in 29%, serum parathormone was >600 pg/ml in 18% (5), and cardiovascular disease was reported by 7.3% of them (registry data) (8). Additionally, the percentages of positive serology for hepatitis C, hepatitis B, and HIV were 3.2%, 0.7%, and 0.9%, respectively. The majority of susceptible patients receive hepatitis B vaccination at the beginning of the dialysis program. Notably, the serum positivity for the hepatitis C virus has consistently dropped in the past years (4–6).

The percentages of patients using selected medications were 77% using erythropoietin, 50% using intravenous iron, 42% using sevelamer, 29% using calcitriol, 11% using cinacalcet, and 6% using paricalcitol. An estimated 31,226 patients (24%) were on the deceased donors’ waiting list by July 2018. The estimated number of deaths in 2018 was 25,187, yielding a crude death rate of 20%, which has remained stable during the past years despite the increasing proportion of elderly patients and patients with comorbidities.

Human Resources and Capabilities

The number of dialysis centers has progressively increased in the country, reaching 781 in 2018; they are distributed mainly in the southeast (47%), south (20%), and northeast regions (18%), and only 6% were in the north region. Dialysis centers were mainly private (72%). Forty-eight percent of the units were hospital based. Most units that assisted patients were reimbursed by either the public system or private health care insurance (70%), whereas 18% and 12% cared only for patients covered by the public system or private health insurance, respectively. Dialyzers were reused in most HD units, except for subjects with positive serology for hepatitis B, hepatitis C, or HIV. Regarding the dialysis machine vintage, 9% were <1 year, 47% were between 1 and 6 years, and 44% were >6 years. All dialyzers’ membranes used were of synthetic material; 81.5% of the patients on HD had a Kt/V≥1.2 in the last month (4).

There were about 4030 nephrologists in the country (19.3 pmp) in 2018. Ninety-five percent of all nephrologists working in dialysis units were national board certified. The average number of patients in the dialysis unit per nephrologist was 26:1, reaching 33:1 in the north region and 23:1 in the midwest (23:1). Typically, the nephrologist stays in the unit during the whole dialysis procedure and personally assists the patients whenever necessary. Physician office visits are scheduled once a month. The nephrology-licensed nurse-to-patient ratio per dialysis shift was about 30:1; the corresponding number for patient care technicians was 2–4:1. Each dialysis unit is required to have a dietician, a psychologist, and a social worker on the permanent staff.

Funding for Dialysis Treatment

In 2014, the government established more structured guidelines and financial incentives encompassing the assistance of patients with CKD at earlier stages. The government spends about 4% (US$1.36 billion) of the annual budget of the Ministry of Health on the treatment of patients undergoing RRT. Overall, 80% of the patients on maintenance dialysis are financed by the public health system, and 20% of the patients on maintenance dialysis are financed by private health insurance companies. The relative contribution of the latter has increased in the past years. Table 2 shows the distribution of patients by dialysis therapy according to the financing source.

Table 2.

Characteristics of dialysis treatment in Brazil, 2018

| Characteristics | |

| No. of patients on dialysis (N/1,000 general population) | 133,464 (0.640) |

| Patients on home dialysis, % | |

| Automated or continuous ambulatory peritoneal | 7.6 |

| Hemodialysis | 0.1 |

| All dialysis sessions covered by insurance | Yes |

| Patients have out-of-pocket expenses? | No |

| Unit location, % | |

| Hospital based | 48 |

| Freestanding | 52 |

| Economic purpose of the dialysis unit | |

| For profit | Yes |

| Nonprofit | — |

| Reimbursement per hemodialysis session, US$ | |

| Public | 53 |

| Private insurers | 105 |

| Dialysis staff members who deliver dialysis | |

| Nurses | Yes |

| Patient care technicians | Yes |

| Patient-to-registered nurse ratio in the unit | 35:1 |

| Average length of dialysis session, h | 4 |

| Times per month that a patient is seen by the nephrologist during the session | 12 |

| Vascular access to hemodialysis, % | |

| Arteriovenous fistula | 73.8 |

| Vascular graft | 2.6 |

| Central venous catheter | 23.6 |

Public system reimbursement per HD session was US$53 (US$689/mo) in 2018; for ambulatory PD, it was US$780/mo in 2018, and for continuous ambulatory PD, it was US$612/mo in 2018 (Brazilian reals converted into United States dollars on the basis of the average exchange rates for 2018; US$1.00=R$3.68). The government does not fund home HD. Compared with HD, the lower rate of PD use in the country cannot be explained by differences in reimbursement. The corresponding average estimates for private health insurers were US$105 (US$1365/mo), US$1064, and US$1030, respectively. These values of reimbursement are intended to cover medical and nonmedical items. Aside from these values, the dialysis centers receive reimbursement for the routine laboratory examinations. Additionally, all patients are eligible to receive directly from the government without expenses medications, such as erythropoietin, sevelamer, calcitriol, and cinacalcet, if clinically indicated.

Using these estimates, the annual costs per patient on maintenance HD would be US$8268/yr and US$16,380/yr in 2018 in the public and private insurance perspectives, respectively. If the costs of the mentioned medications were added, these estimates would increase by at least 40%. In an extensive cost evaluation analysis carried out in 2009, including most direct and indirect costs, we estimated that the annual costs were US$28,570 and US$27,158 per patient-year for HD and PD, respectively (10). Recently, many dialysis managers have sold their units, arguing that the government reimbursement rate for HD sessions is too low and falls short of the needs. Concomitantly, using a more efficient management, large multinational dialysis organizations (e.g., DaVita, Fresenius, and Diaverum) have acquired many dialysis units, increasing their presence in the country (about 15% of the units).

There has been a continuous increase in the prevalence and incidence rates of maintenance dialysis treatment in Brazil. The costs of the procedures continue to rise, and there is an enormous economic burden for the government to maintain the program. There are permanent challenges to develop a more cost-effective and economically sustainable treatment for those with advanced disease, to guarantee access to treatment, and to keep providing a high quality of care.

Disclosures

J. Lugon and R. Sesso have nothing to disclose.

Author Contributions

R. Sesso conceptualized the study, was responsible for formal analysis as well as investigation and methodology, and wrote the original manuscript; and J. Lugon was responsible for investigation and methodology, and reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Footnotes

This article contains a podcast at https://www.asn-online.org/media/podcast/K360/2020_03_26_KID0000642019.mp3

References

- 1.Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística IBGE : Estimativas da População, 2019. Available at: https://www.ibge.gov.br/estatisticas/sociais/populacao.html. Accessed December 2, 2019

- 2.The World Bank : World Development Indicators Database, 2019. Available at: https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators. Accessed December 2, 2019

- 3.Lugon JR: End-stage renal disease and chronic kidney disease in Brazil. Ethn Dis 19[Suppl 1]: S1-7-9, 2009 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sesso RC, Lopes AA, Thomé FS, Lugon JR, Dos Santos DR: Brazilian Chronic Dialysis Survey 2013 - trend analysis between 2011 and 2013. J Bras Nefrol 36: 476–481, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thomé FS, Sesso RC, Lopes AA, Lugon JR, Martins CT: Brazilian chronic dialysis survey 2017. J Bras Nefrol 41: 208–214, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sociedade Brasileira de Nefrologia : Censo de diálise SBN, 2015. Available at: http://www.censo-sbn.org.br/censosAnteriores. Accessed November 20, 2019

- 7.Sesso R, Fernandes PF, Anção M, Drummond M, Draibe S, Sigulem D, Ajzen H: Acceptance for chronic dialysis treatment: Insufficient and unequal. Nephrol Dial Transplant 11: 982–986, 1996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lugon JR, Gordan PA, Thomé FS, Lopes AA, Watanabe YJA, Tzanno C, Sesso RC: A web-based platform to collect data from ESRD patients undergoing dialysis: Methods and preliminary results from the Brazilian dialysis registry. Int J Nephrol 2018: 9894754, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.United States Renal Data System: US Renal Data System 2019 Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of Kidney Disease in the United States, Bethesda, MD, United States Renal Data System and National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Abreu MM, Walker DR, Sesso RC, Ferraz MB: A cost evaluation of peritoneal dialysis and hemodialysis in the treatment of end-stage renal disease in Sao Paulo, Brazil. Perit Dial Int 33: 304–315, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]