Introduction

Governor Cuomo recently stated, “We will lose people, the virus takes the most vulnerable. The challenge is to make sure we don’t lose anyone else we could have saved.”

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, known as COVID-19, was first described in China in December 2019 (1). A global pandemic followed in the months to come, leading to devastating consequences. By April 26, 2020, COVID-19 had spread to >200 countries, infecting >2.9 million people, and resulting in >200,000 deaths globally (2). The suspected index case of COVID-19 infection leading to the New York City/Westchester outbreak was described in a man who became ill on February 22. By the third week of March, New York City had become an epicenter of the COVID-19 outbreak in the United States. Nearly 1 million Americans have been infected with the virus and New York accounts for 29% of these infections. Never in our lifetime have so many people fallen ill simultaneously. The rapid increase in hospitalizations has challenged the delivery of health care in unprecedented ways. AKI has been reported in up to 25% of patients with severe COVID-19 infection (3,4). The volume of patients with severe AKI in a single hospital poses unique challenges for the nephrologist including (1) infection prevention (2) workforce (3) dialysis resources, and (4) communication. We report our experience of providing care to hospitalized patients with AKI in the Bronx during the first month of the outbreak.

The Bronx Experience: AKI in COVID-19-Infected Patients

Montefiore Medical Center (MMC), located in the North Bronx in close proximity to Westchester County, has been one of the main urban tertiary care centers for patients in New York City with COVID-19 infection. MMC’s two main campuses are the Moses and Weiler Hospitals. Moses Hospital is a 726-bed hospital with five intensive care units (ICUs) (47 beds) and Weiler Hospital is a 431-bed hospital with two ICUs (32 beds). Each hospital has ten clinical nephrology faculty and four nephrology fellows. The Moses and Weiler Hospitals have 20 and 12 full-time dialysis nurses, respectively. Before COVID-19, there were two nephrology consult services and two ESKD services at Moses Hospital, and one nephrology consult service and one ESKD service at Weiler Hospital. One nephrologist with a fellow or physician assistant staffed each service. The average number of consultations for AKI was 10–15 per day at each hospital and the average census of each consult service was 20–25 patients.

On March 10, 2020, the first confirmed COVID-19-infected patient was transferred from Westchester to MMC. This patient had AKI and immediately required RRT. By April 6, the number of COVID-19 patients had increased to 877. Simultaneously, there was a significant increase in the number of consultations for AKI associated with COVID-19 infection and in those who needed acute RRT. (Table 1) Between March 10 and March 30, 2020, there were 112 nephrology consultations for AKI. The average age of these patients was 63 years; 69% were men, the majority were black or Hispanic, and diabetes mellitus, hypertension, CKD, and obesity were prevalent comorbidities. Most presented to the emergency department with AKI or started to develop AKI within 24 hours of admission, underscoring their severity of illness at presentation. The average time to RRT was 7 days and the most common indications for RRT were hyperkalemia and volume overload. Approximately 54% required ICU admission and 46% required RRT. To handle these high-acuity patients, the number of ICU beds increased by 60% and the number of nephrology services was expanded (Table 1).

Table 1.

Surge in weekly census of COVID-19 confirmed patients with AKI at Montefiore Medical Center

| March 10–16 | March 17–23 | March 24–30 | March 31–April 6 | |

| Weekly AKI consults | 12 | 38 | 62 | 78 |

| Weekly acute RRT | 4 | 10 | 52 | 75 |

| Weekly hospital COVID-19 patient census | 2–18 | 26–163 | 233–560 | 625–877 |

| IExpansion of intensive care units | 7 | 7 | 9 | 16 |

| Expansion of nephrology services | 6 | 6 | 8 | 10 |

A Nephrology Task Force was created to develop strategies to handle workflow and the expanding census of patients with AKI and acute RRT (Table 2).

Table 2.

Timeline and evolution of strategies for treating AKI in COVID-19-infected patients

| Strategy | Date |

| Formation of Nephrology Task Force | March 16 |

| Back-up schedules created | |

| High-risk staff shifted from inpatient services to lower-risk settings | |

| Purchase of additional CRRT and HD machines | March 17 |

| Installation of additional dialysis compatible plumbing for bedside dialysis | March 18 |

| Tubing extension for CRRT machine to place it outside the room | |

| NxStage Fresenius CAR 502–4.5 feet extension | |

| Reduction in HD frequency and treatment time in patients with ESKD who could tolerate that schedule | March 21 |

| Twice weekly HD for 2.5 h with low-potassium bath | |

| Typical schedule: Monday-Thursday, Tuesday-Friday, Wednesday-Saturday | |

| Potassium binders in patients with normokalemia (K>4 meq/L) but rising potassium level | |

| Sodium zirconium cyclosilicate 10 g daily | |

| Patiromer 8.4 g daily, uptitrated to 16.8 or 25.5 g as needed | |

| Diuretics to maintain euvolemia (furosemide 80 mg iv q 8–12 h or bumetanide 2–4 mg iv every 12 h with chlorthiazide 250 mg iv every 12 h in those with severe AKI and fluid overload) | |

| PIRRT treatments to allow treatment of 2–3 patients/d with one CRRT machine | |

| NxStage machine, CVVHD | |

| Blood flow rate: 250 ml/h for CVVHD and 300–350 ml/h for PIRRT | |

| Effluent flow rate: 25 ml/kg per h in CVVHD and 40–50 ml/kg per h in PIRRT | |

| Treatment time: 24 h for CVVHD and 6–12 h for PIRRT | |

| Dialysate fluid: RFP 400 (2 K bath), RFP 401 (4 K bath) | |

| Recovering patients with COVID-19 without a fever for at least 3 d started to be cohorted together on last inpatient HD shift followed by terminal disinfection | March 24 |

| Near capacity for inpatient HD due to majority requiring 1:1 nursing care | March 27 |

| Telemonitoring during HD treatments to minimize nurse exposure | |

| First patient started on acute PD | |

| Expanded inpatient nephrology services | |

| Inpatient HD unit started to open on Sundays | March 29 |

| Increased from 1 to 3 on call dialysis nurses | |

| Expansion and creation of 11 new COVID-19 intensive care units | |

| PD program initiated to increase capacity for acute dialysis | March 30 |

| Typical manual PD initial prescription: 1–2-L dwells every 2–4 h | |

| PD cyclers ordered to begin automated PD | |

| Inpatient E-consultations for nephrology went live | |

| Creation of acute PD service | April 1 |

| Nephrologist in-service training on performing PD exchanges to assist nursing staff | |

| Perfusionist reappointed to assist with PIRRT/CRRT | April 2 |

| Initiated bivalirudin anticoagulation protocol for PIRRT/CRRT clotting | |

| Bolus: 0.50 mg/kg bolus 1 h before PIRRT/CRRT | |

| Maintenance: 0.25 mg/kg per h 30 min before PIRRT/CRRT | |

| Stop 1 h before end of PIRRT | |

| Check activated clotting time 15 min into treatment and PTT 4 h into treatment | |

| Goal PTT 1.5–2× normal | |

| Nephrologists training nurses to perform PD | April 5 |

| Started to use PD cyclers (Baxter) (typical prescription: five exchanges of 1.8-L volume over 10 h with 1.5-h dwell time) | |

| Nephrologists began assisting in performing HD due to nursing staff shortage from illness (primed the machines, monitored patients on dialysis, applied pressure to the access at the end of treatment) | |

| Majority of both hospitals COVID-19 positive, all patients now being dialyzed in the inpatient HD unit | April 9 |

CRRT, continuous renal replacement therapy; HD, hemodialysis; CAR, cartridge; PIRRT, prolonged intermittent renal replacement therapy; RFP, replacement fluid pureflow; CVVHD, continuous venovenous hemodialysis; PD, peritoneal dialysis; COVID-19, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; PTT, partial thromboplastin time.

Infection Prevention

Mitigating transmission of COVID-19 infection to other patients and hospital staff has been a major priority. To prevent the spread of infection, initially all COVID-19-infected patients requiring RRT received hemodialysis (HD) treatments at bedside. In order to expand the capability of providing bedside HD, hospital rooms were replumbed for access to the central reverse osmosis system, portable reverse osmosis was used, and ten additional HD machines were purchased from Fresenius. A limitation in providing bedside HD was the requirement of 1:1 nursing. As the number of COVID-19-infected patients increased, there was also a two- to threefold increase in the number of patients requiring bedside HD. To accommodate the increase in patients requiring bedside HD, patients with ESKD were placed on a twice-weekly schedule and treatments were shortened using higher blood and dialysate flow for those who could tolerate it. Those with AKI were managed with maximal medical management to delay RRT initiation. A novel approach to prevent or slow hyperkalemia from developing was initiation of potassium binders (patiromer or sodium zirconium cyclosilicate) in patients with a serum potassium between 4.0 and 5.0 meq/L that was rising. Nonoliguric patients were placed on diuretics to maintain euvolemia.

Whenever possible, the number of staff entering infected patient rooms was limited to minimize exposure and preserve personal protective equipment (PPE). Nephrology teams performed remote assessment by reviewing the electronic record, laboratory data, and imaging. The most common reason for the nephrologist to directly interact with a COVID-19-infected patient was to discuss initiation of RRT or to place acute dialysis access. Telemonitoring was piloted using baby monitors with two-way video and audio, positioned next to the patient and dialysis machine, allowing the nurse to monitor the patient remotely during treatment. Tubing extension for continuous RRT (CRRT) was purchased to allow positioning of CRRT machines outside of the ICU rooms so the nurses could adjust ultrafiltration rates and check on machine alarms without the need to put on PPE to perform this task. Despite these interventions, capacity was reached in providing bedside HD near the end of March. After consultation with infection control, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s recommendation to cohort COVID-19-infected patients together on the last shift of the day in the inpatient HD unit was used (5,6).

Workforce

By the third week of March, the volume of patients with COVID-19-associated AKI and acute RRT needs increased significantly. Nephrology services were expanded to handle the increase in consultations for AKI. Moses Hospital increased from four to seven services and Weiler Hospital increased from two to three services. The average daily census of each service was 20–25 patients. Providers identified as high risk for severe complications from COVID-19 infection (>65 years old or pregnant) were relocated from inpatient services to lower-risk settings, including night call coverage, electronic inpatient nephrology consultations, and outpatient office and HD telemedicine visits. Further complicating staffing was more than a 50% reduction in available dialysis nurses and technicians due to illness for 2 weeks. As a result, nephrologists assisted with HD by priming the machines, monitoring patients during the dialysis treatments, and achieving hemostasis to the access at the end of the treatment. On March 29, 2020, the inpatient HD unit opened on Sundays to meet the number of patients requiring acute RRT.

Dialysis Resources

The availability of dialysis resources decreased due to the surge in patients with COVID-19 with AKI requiring RRT (7). CRRT is the preferred treatment modality in patients presenting with acute respiratory distress syndrome requiring intubation and prone positioning. However, patients with this presentation quickly depleted the ability to provide CRRT for 24-hour periods per patient. Treatment times were reduced and dialysate flow rates were increased to convert CRRT to prolonged intermittent renal replacement treatments (PIRRT). PIRRT was performed for 6–12-hour treatments with effluent flow rates of 40–50 ml/kg per hour. This permitted the use of one machine for two to three patients with time for disinfection in between patients. Despite these adaptions, the surge in patients required the creation of 11 additional ICUs. As a result, the nurse-to-patient ratio increased significantly, which made it impossible for ICU nurses to manage 1:1 nursing requirements for PIRRT. Perfusionists who ordinarily manage extracorporeal membrane oxygenation procedures were reassigned and assumed the role of PIRRT management during the day. Before the International Society of Thrombosis and Hemostasis guidance for the recognition and management of the hypercoagulable state in patients with COVID-19, ICU patients on CRRT were observed to have increased clotting of catheters and filters despite therapeutic heparin infusion (partial thromboplastin time 2× normal), which led to frequent treatment interruptions and difficulty in achieving adequate clearance (8). To resolve the issue with clotting on CRRT, a nonvalidated bivalirudin protocol was initiated with close monitoring of partial thromboplastin time (8).

By early April, our COVID-19 RRT census included 25–30 patients with AKI on CRRT or PIRRT, 20 patients with AKI on HD, and 65 patients with ESKD on HD. To meet the increasing need for acute RRT, an acute peritoneal dialysis (PD) service was created. Transplant surgeons placed Tenkhoff catheters at bedside in intubated patients and interventional radiologists placed catheters in floor patients via fluoroscopy. Within 1 week, 18 patients were initiated on acute PD. Manual PD exchanges were initiated immediately after catheter placement using 1–2-L dwells with exchanges every 2–3 hours. Major barriers identified in effective delivery of this modality were nurse training and frequent prone positioning of ventilated patients. To overcome these barriers, nephrologists and fellows received in-service training on how to perform manual PD exchanges, and assisted nursing staff with limited experience. Additionally, PD cyclers were purchased from Baxter that reduced workload and staff exposure. The majority of patients with AKI requiring acute RRT who were selected for PD were nonintubated, hemodynamically stable patients. CRRT or PIRRT was preferentially used in patients who were hemodynamically unstable, those requiring prone positioning for acute respiratory distress syndrome, and those with severe electrolyte abnormalities.

Communication

Bedside evaluation plays an important role in AKI management. However, during the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been a shortage of PPE. In an effort to preserve PPE, daily patient contact by specialists has been minimized. This has been a challenge, because intravascular volume assessment is important in determination of the need for intravenous fluids, diuretics, or RRT in those with AKI. Many patients with COVID-19-associated AKI also present with respiratory failure and chest x-ray findings of bilateral lung opacities with a ground glass appearance that is difficult to distinguish from pulmonary edema. In these patients, the desire to reduce hypervolemia to optimize respiratory status must be balanced against overdiuresis, which may further exacerbate AKI. Point-of-care ultrasound has been useful in assessing intravascular volume status, as well as frequent communication with the primary teams and reliance on their physical examination findings. To limit indwelling bladder catheters, nurses have been performing bladder scans to rule out urinary retention and determine urine output for intake and output assessment. “Often out of periods of losing come the greatest strivings toward a new winning streak.”

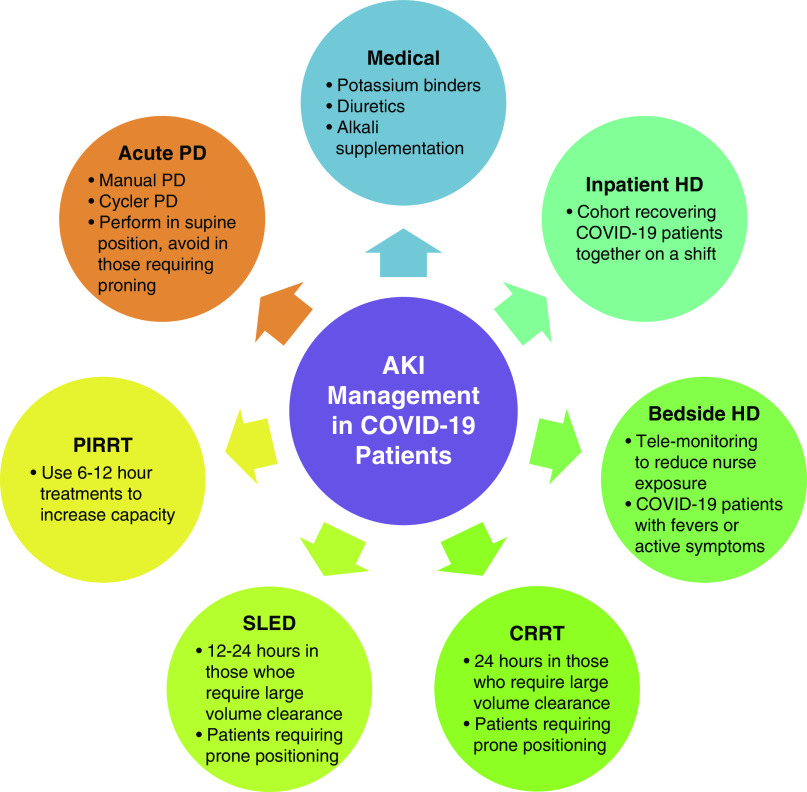

Despite the enormous challenges faced during the COVID-19 pandemic, this experience has taught us how to be resourceful in maximizing the availability of acute AKI and RRT services to meet the needs of our patients, even in the most trying circumstances. The best advice we can offer from New York to nephrologists across the world where COVID-19 may still be in its early stages is the following: plan ahead, get creative, support each other, and work together. Hopefully, we will never see another pandemic in our lifetime, but if we do we will be prepared (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Management Considerations in COVID-19 Patients with AKI. Selection of the management strategy for AKI associated with COVID-19 infection depends on several factors; (1) patient factors including hemodynamic stability, volume status, acid-base status, candidate for acute central venous catheter insertion versus PD catheter, and goals for fluid removal and clearance of uremic toxins; (2) nursing staff availability and expertise; (3) supply inventory of machines and materials; and (4) the location of the RRT procedure including appropriate HD plumbing, need for isolation precautions, and patient transport safety to avoid transmission to others. COVID-19, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; CRRT, continuous renal replacement therapy; HD, hemodialysis; PD, peritoneal dialysis; PIRRT, prolonged intermittent renal replacement therapy; SLED, sustained low efficiency dialysis.

Disclosures

All authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

None.

Acknowledgments

We would like to dedicate this article to our nephrology task force including Dr. M. Ross, Dr. E. Akalin, Dr. M. Brogan, C. Cahill, Dr. M. Coco, Dr. L. Golestaneh, Dr. M. Mokrzycki, Dr. M. Melamed, Dr. J. Neugarten, Dr. D. Sharma, L. Tingling MSN, Dr. J Yoo, and our nephrology faculty, fellows, and dialysis nurses for their hard work and commitment to patient care.

Author Contributions

M. Fisher conceptualized the study, and was responsible for resources and visualization; M. Fisher, L. Golestaneh, and K. Prudhvi wrote the original draft; and all authors reviewed and edited the manuscript.

References

- 1.Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, Li X, Yang B, Song J, Zhao X, Huang B, Shi W, Lu R, Niu P, Zhan F, Ma X, Wang D, Xu W, Wu G, Gao GF, Tan W; China Novel Coronavirus Investigating and Research Team : A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med 382: 727–733, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.John Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center: COVID 19 United States cases by county . Available at: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/us-map. Accessed April 26, 2020

- 3.Naicker S, Yang CW, Hwang SJ, Liu BC, Chen JH, Jha V: The Novel Coronavirus 2019 epidemic and kidneys. Kidney Int 97: 824–828, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheng Y, Luo R, Wang K, Zhang M, Wang Z, Dong L, Li J, Yao Y, Ge S, Xu G: Kidney disease is associated with in-hospital death of patients with COVID-19. Kidney Int 97: 829–838, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Society of Nephrology recommendations on the care of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 and kidney failure requiring Renal Replacement Therapy. Available at: https://www.asn-online.org/g/blast/files/AKI_COVID-19_Recommendations_Document_03.21.2020.pdf. Accessed April 26, 2020

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention : Steps healthcare facilities can take now to prepare for COVID-19, 2020. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/healthcare-facilities/steps-to-prepare.html. Accessed April 26, 2020

- 7.Burgner A, Ikizler TA, Dwyer JP: COVID-19 and the Inpatient Dialysis Unit: Managing Resources during Contingency Planning Pre-Crisis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 15[5]: 720–722, 2020. 10.2215/CJN.03750320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barrett CD, Moore HB, Yaffe MB, Moore EE: ISTH interim guidance on recognition and management of coagulopathy in COVID-19: A comment [published online ahead of print April 17, 2020]. J Thromb Haemost doi: 10.1111/jth.14860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]