Abstract

We provide a general framework for understanding functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs) from a biopsychosocial perspective. More specifically, we provide an overview of the recent research on how the complex interactions of environmental, psychological, and biological factors contribute to the development and maintenance of FGIDs. We emphasize that considering and addressing all these factors is a conditio sine qua non for appropriate treatment of these conditions. First, we provide an overview of what is currently known about how each of these factors—the environment, including the influence of those in an individual’s family, the individual’s own psychological states and traits, and the individual’s (neuro)physiological make-up—interact to ultimately result in the generation of FGID symptoms. Second, we provide an overview of commonly used assessment tools that can assist clinicians in obtaining a more comprehensive assessment of these factors in their patients. Finally, the broader perspective outlined earlier is applied to provide an overview of centrally acting treatment strategies, both psychological and pharmacological, which have been shown to be efficacious to treat FGIDs.

Keywords: Adverse Life Events, Anxiety, Depression, Psychological Treatments

Biopsychosocial Basis of the Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders

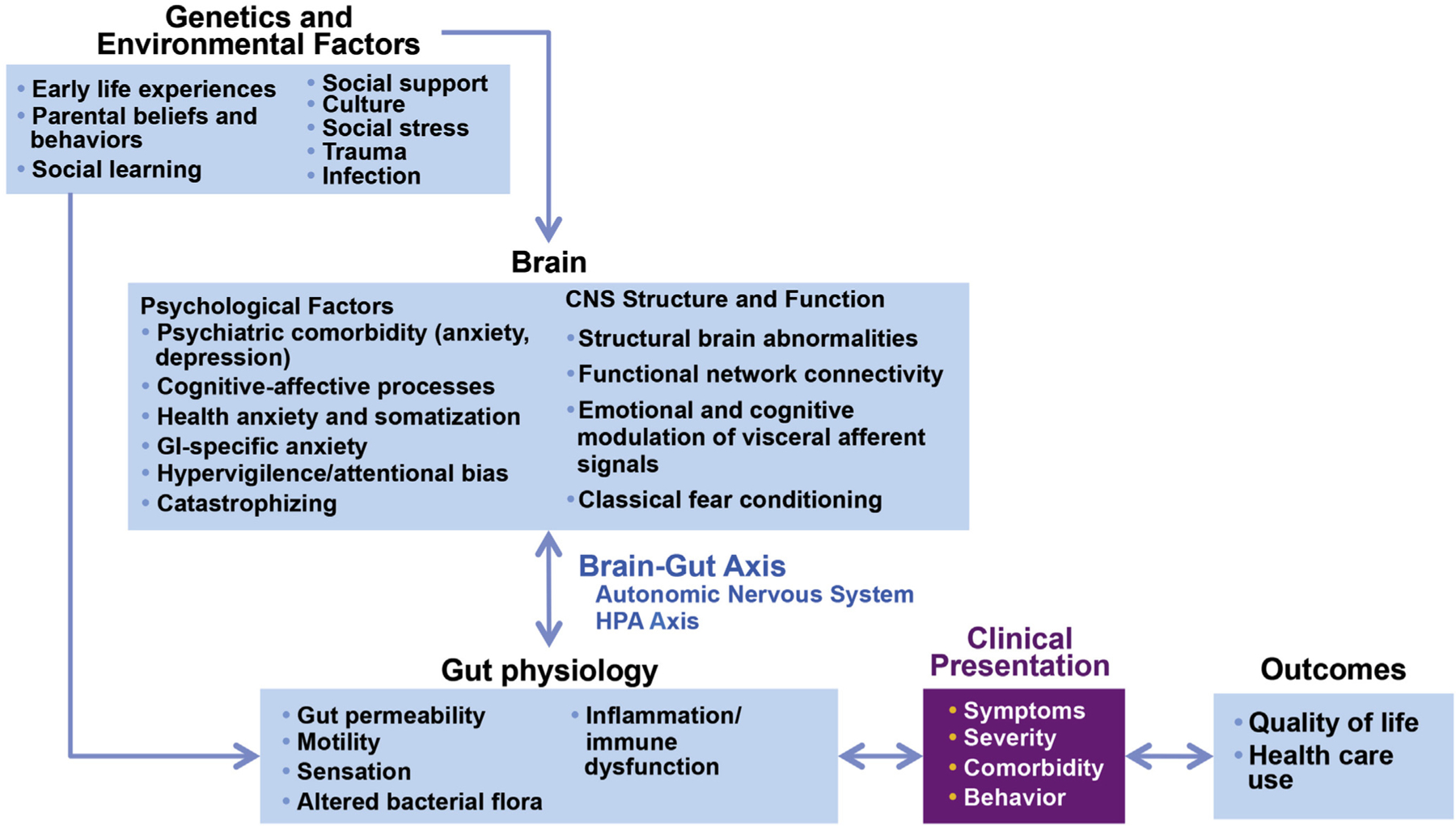

It is generally accepted that functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs) result from complex and reciprocal interactions between biological, psychological, and social factors, rather than from linear monocausal etiopathogenetic processes. This consensus report, based on an extensive critical literature review by a multidisciplinary expert committee, aims to provide a framework for understanding FGID from a biopsychosocial perspective. Further, we emphasize why and how knowledge of this biopsychosocial framework is critical for assessment and treatment of these difficult-to-treat disorders that often induce uncertainty and frustration in caregivers and patients alike. The many processes that are part of these complex interactions of the individual’s physiology, psychology, and environment are illustrated in an overview of the biopsychosocial model of FGID (Figure 1) and described further.

Figure 1.

Biopsychosocial Model of IBS. Genetic and environmental factors, such as early life experiences, trauma, and social learning, influence both the brain and the gut, which in turn interact bidirectionally via the autonomic nervous system and the HPA axis. The integrated effects of altered physiology and the person’s psychosocial status will determine the illness experience and ultimately the clinical outcome. Furthermore, the outcomes will in turn affect the severity of the disorder. The implication is that psychosocial factors are essential to the understanding of IBS pathophysiology and the formulation of an effective treatment plan. Figure adapted from Drossman et al,109 with permission.

Environmental Influences

Childhood environmental factors: parental beliefs and behaviors.

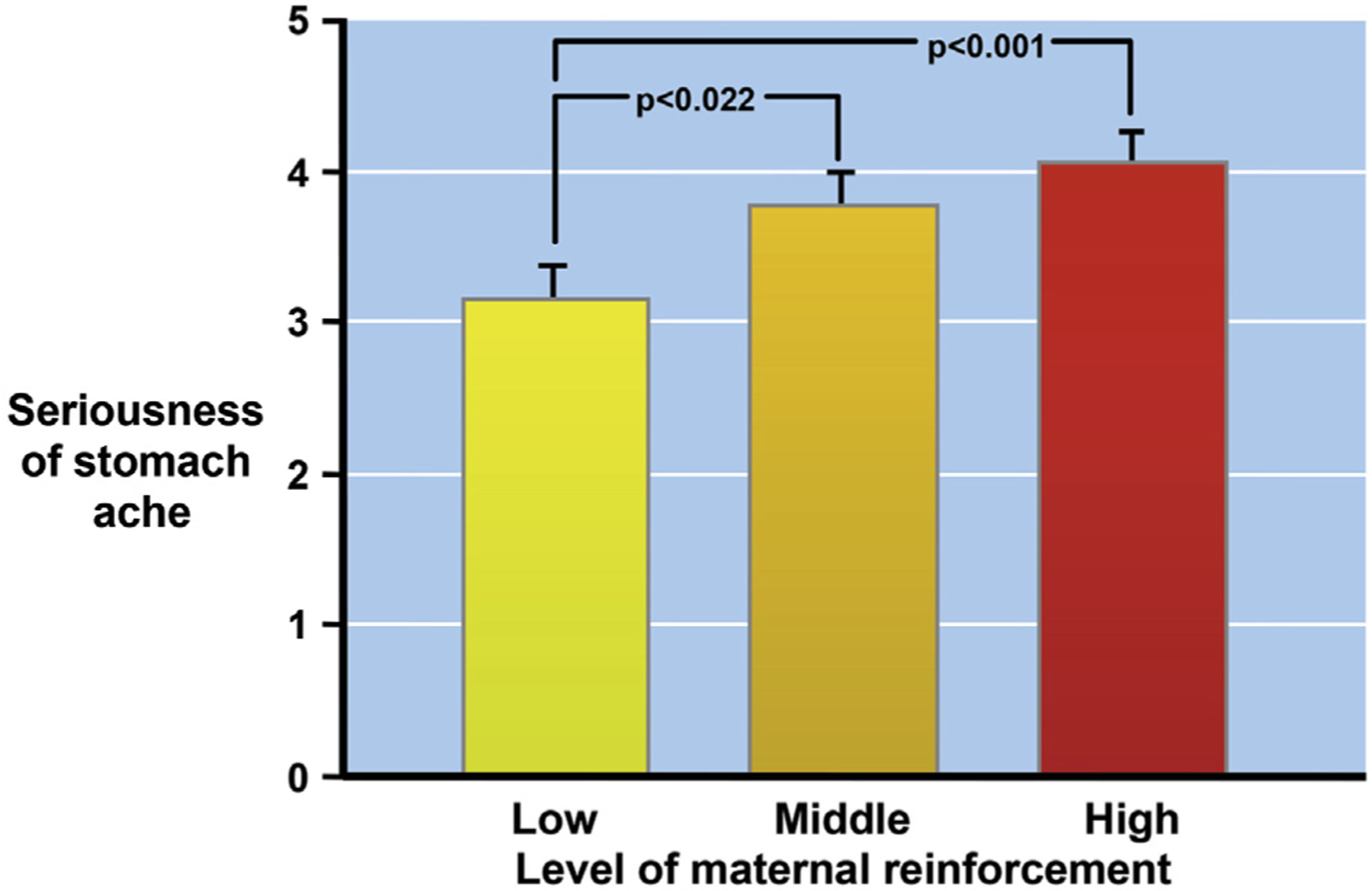

There is familial aggregation of childhood FGID.1 Children of adult irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) patients make more health care visits than the children of non-IBS parents. This pattern is not confined to gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms2 and holds for maternal and paternal symptoms.3,4 Although there is ongoing research into a genetic explanation for these familial patterns, what children learn from parents can make an even greater contribution to the risk for developing an FGID than genetics.5 The basic learning principle of positive reinforcement or reward, defined as an event following some behavior that increases the likelihood of that behavior occurring in the future, is a likely contributor to how this can occur. Children whose mothers reinforce illness behavior experience more severe stomachaches and more school absences than other children6 (Figure 2). In addition, when parents were asked to show positive or sympathetic responses to their children’s pain in a laboratory, the frequency of pain complaints was higher than when parents are instructed to ignore them.7 Finally, a large randomized clinical trial of children with functional abdominal pain found that cognitive-behavioral treatment (CBT) targeting coping strategies, as well as parents’ and children’s beliefs about, and responses to, children’s pain complaints, induced greater baseline to follow-up decreases in pain and GI symptoms compared with an educational intervention controlling for time and attention,8 and that this effect was mediated by changes in parents’ cognitions about their child’s pain.9

Figure 2.

Associations between maternal reinforcement and parental IBS, and illness behavior. In addition to increased reported severity, children whose mothers strongly reinforce illness behavior also experience more school absences than other children. Figure adapted from Levy et al,6 with permission.

There is also a strong association between parental psychological status, particularly anxiety, depression, and somatization, and children’s abdominal symptoms.4,10,11 This association could be occurring through modeling—children observing and learning to display the behaviors they observe, in this case, possibly heightened attention to, or catastrophizing about, somatic sensations. However, the effect of parental traits on children’s symptoms could also occur through reinforcement. Parents with certain traits or beliefs, such as excessive worry about pain, might pay more attention to, and thereby reward, somatic complaints. Parents’ catastrophizing cognitions about their own pain predicted responses to their children’s abdominal pain that encouraged illness behavior, which in turn predicted child functional disability.12

Environmental stressors in childhood and adult life.

Adverse life events (including sexual, physical, and emotional abuse).

Compared with controls, IBS patients report a higher prevalence of adverse life events in general, and physical punishment, emotional abuse, and sexual abuse in particular13; such history is related to FGID severity and clinical outcomes, such as psychological distress, and daily functioning.14 This in turn leads to increased health care seeking, which could explain the higher association of abuse histories with GI illness in referral centers compared with primary care.14 Population-based studies have led to more conflicting results with regard to the association between self-reported FGIDs and abuse history.15,16 Further, it should be noted that high frequencies of childhood abuse (approaching 50%) are not unique to patients with FGID, as similar figures are found in patients with non-GI functional somatic syndromes (FSS, eg, pelvic pain, headaches, and fibromyalgia).17

The onset of FGIDs has been associated with the experience of severely threatening events, such as the breakup of an intimate relationship. In one study, two-thirds of patients had experienced such an event compared with one-quarter of healthy controls.18

Prospective studies have demonstrated that the experience of stressful life events is associated with symptom exacerbation and frequent health care seeking among adults with IBS.19,20 Chronic life stress is the main predictor of IBS symptom intensity over 16 months, even after controlling for relevant confounders.21

Finally, stress can affect FGID treatment outcomes—one study demonstrated that the presence of a single stressor within 6 months before participation in an IBS treatment program was directly associated with poor outcomes and higher symptom intensity at 16-month follow-up when compared with patients without exposure to such a stressor.22

Social support.

Quality or lack of social support is related to many aspects of IBS.23 Patients report finding social support as a way to help overcome IBS.24 Relatedly, perceived adequacy of social support is associated with IBS symptom severity, putatively through a reduction in stress levels.25 However, negative social relationships marked by conflict and adverse interactions are more consistently and strongly related to IBS outcomes than social support.23 Illustrative of the role of social support and clinically important, a supportive patient‒practitioner relationship significantly improved symptomatology and quality of life in patients with IBS.26

Culture.

Cultural beliefs, norms, and behaviors affect all aspects of what has been discussed in this section: interactions within the family, with other support systems, and the world at large. For more extensive discussion, see the article in this issue regarding multicultural aspects of FGIDs.

Psychological Distress

Psychological distress is an important risk factor for the development of FGIDs and, when present, can perpetuate or exacerbate symptoms. Further, it affects the doctor‒patient relationship and negatively impacts treatment outcomes. However, psychological distress can also be a consequence rather than a cause of disease burden.

Comorbid anxiety and depression are independent predictors of post-infectious IBS and functional dyspepsia (FD) but, at the same time, also occur as a consequence of bodily symptoms and related quality of life impairment. The absence of formal psychiatric comorbidity does not exclude a role of dysfunctional cognitive and affective processes not captured by the current psychiatric classification system(s) (in the sense of not reaching the threshold for a psychiatric disorder or not being included in the classification system, eg, in the case of symptom-specific anxiety, which is relevant in the context of FGID but does not constitute a psychiatric disorder).

Mood disorders.

Overlap between depression and FGID is about 30% in primary care settings and slightly higher in tertiary care.27 Depression can impact the number of functional GI symptoms experienced or the number of FGID diagnoses.28,29 Suicidal ideation is present in between 15% and 38% of patients with IBS, and has been linked to hopelessness associated with symptom severity, interference with life, and inadequacy of treatment.30 Comorbid depression has been linked to poor outcomes, including high health care utilization and cost, functional impairment, poor quality of life, and poor treatment engagement and outcomes.25,31

Anxiety disorders.

Anxiety disorders are the most common psychiatric comorbidity, occurring in 30%‒50% of FGID patients. They may initiate or perpetuate FGID symptoms through their associated heightened autonomic arousal (in response to stress) or at the level of the brain, which can interfere with GI sensitivity and motor function. Vulnerability to anxiety disorders might share similar pathways as vulnerability to FGIDs, particularly with respect to anxiety sensitivity, body vigilance, and ability to tolerate discomfort.

Somatization, somatic symptom disorder, and functional somatic syndromes.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition discarded the concept of somatization, originally defined as “a tendency to experience and communicate somatic symptoms unaccounted for by pathological findings in response to psychosocial stress and seek medical help for it,”32 but often operationalized in a descriptive way, measuring somatization by simply quantifying the number of (medically unexplained) symptoms, in favor of somatic symptom disorder.33 In the new diagnostic category, somatic symptoms may or may not be medically unexplained, but are distressing and disabling and associated with excessive and disproportionate thoughts, feelings, and behaviors for more than 6 months.34 This approach shifts the experience of medically unexplained symptoms from (unconscious) manifestations of psychological distress toward abnormal cognitive‒affective processes (eg, excessive illness worry, body preoccupation, and hypochondriasis), both as contributors to, and consequences of, symptoms.35

Somatization is associated with GI sensorimotor processes, including gastric sensitivity and gastric emptying, symptom severity,36 and impaired quality of life in FD.37 Further, somatization is associated with health care use and predicts a poor response to treatment, including increasing one’s likelihood of discontinuing medication due to perceived adverse effects.38 Therefore, assessing somatization by checking severity of multiple somatic symptoms remains clinically useful.

Somatization has been thought to explain the frequent extraintestinal symptoms of IBS, and the high co-occurrence between FGID and other FSS,39 and is a term that is commonly used in the medical literature to refer to medically unexplained syndromes (in parallel with the psychiatric terminology outlined here). There is extensive overlap among FSS—two-thirds of FGID patients experience symptoms of other FSS, including interstitial cystitis, chronic pelvic pain, headaches, and fibromyalgia,40 independent of psychiatric comorbidity, but the question whether the different FSS represent truly distinct disorders (“splitter” view) or different manifestations of a common underlying pathophysiological process (“lumper” view) remains unresolved at present and falls outside the scope of this article.

Cognitive‒affective processes.

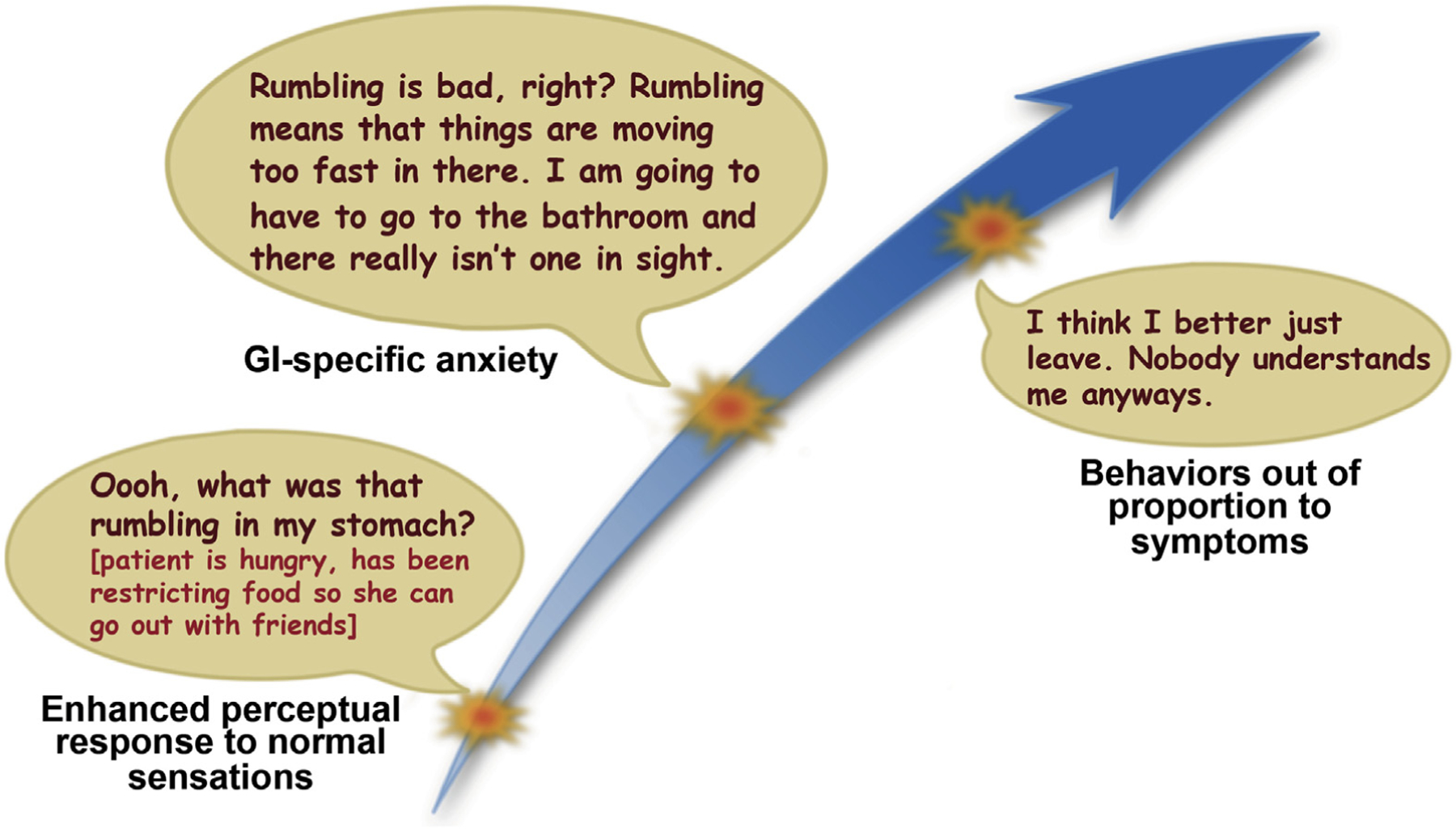

Overlapping psychological constructs, including health anxiety (gastrointestinal) symptom-specific anxiety, attentional bias, symptom hypervigilance, and catastrophizing, have been linked to FGID independent of psychiatric comorbidity, and are important treatment targets for CBT (see Psychological Treatments section)41 (Figure 3). An overview of these processes and their roles in FGID is provided in Table 1.

Figure 3.

Gastrointestinal-symptom specific anxiety: when normal becomes threatening. Gastrointestinal symptom-specific anxiety is an important perpetuating factor of FGID and is characterized by worry and hypervigilance around GI sensations that can range from normal bodily functions (hunger, satiety, gas) to symptoms related to an existing GI condition (abdominal pain, diarrhea, urgency). The worry and hypervigilance usually generalize into fear regarding the potential for sensations or symptoms to occur and/or the contexts in which they may be most likely to present. Gastrointestinal symptom-specific anxiety can result in avoidance and behaviors out of proportion to symptoms.

Table 1.

Cognitive–Affective Processes Influencing the Symptom Experience in Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders

| Term | Definition | Association with FGID | Outcomes | Management |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illness anxiety | Global tendency to worry about current and future bodily symptoms, formerly referred to as hypochondriasis | Low insight Extensive research into what is wrong Not easily reassured, Lack of acceptance Risk factor for development of FGID |

Chronicity Social dysfunction, occupational difficulties, High health costs, Negative doctor–patient relationship, Poor treatment response |

Responsive to CBT |

| Symptom-specific anxiety | Worry/hypervigilance around the likelihood/presence of specific symptoms and the contexts in which they occur | Belief that normal gut sensations are harmful or will lead to negative consequences Promotes GI symptoms |

Drives health care use Negatively impacts treatment response |

Aerophagia improved with distraction May be differentially responsive to interoceptive exposure-based behavior therapy |

| Hypervigilance/attentional bias | Altered attention toward, and increased engagement with, symptoms and reminder of symptoms | IBS patients showed higher recall of pain words and GI words compared with healthy controls NCCP patients hypervigilant toward cardiopulmonary sensations |

Dismiss signs of improvement Ignore information suggesting that their FGID is not serious |

Responsive to CBT |

| Catastrophizing | 2-pronged cognitive process in which an individual magnifies the seriousness of symptoms and consequences while simultaneously viewing themselves as helpless | Results in symptom amplification Increased pain Inhibits pain inhibition Negatively affects interpersonal relationships Leads to increased worry, suffering, disability |

High symptom reporting Reduced quality of life Can impact patient self-report Burdens provider |

Improves with CBT Mediates outcome |

NCCP, noncardiac chest pain.

Mechanisms: The Neurophysiological Basis of the Biopsychosocial Model

Here we give an overview of the neurophysiological mechanisms that explain the link between psychological processes, psychiatric comorbidity, and FGID symptoms described in the previous sections. Specifically, the critical role of bidirectional signaling mechanisms between the GI tract and the central nervous system are discussed, including the central processes involved in modulation of visceral afferent signals and the influence of efferent output of central stress and emotional‒arousal circuits on motor, barrier, and immune functions of the GI tract. Finally, the emerging evidence on bidirectional communication between the gut microbiota and the (emotional) brain is outlined briefly.

Brain‒gut processing.

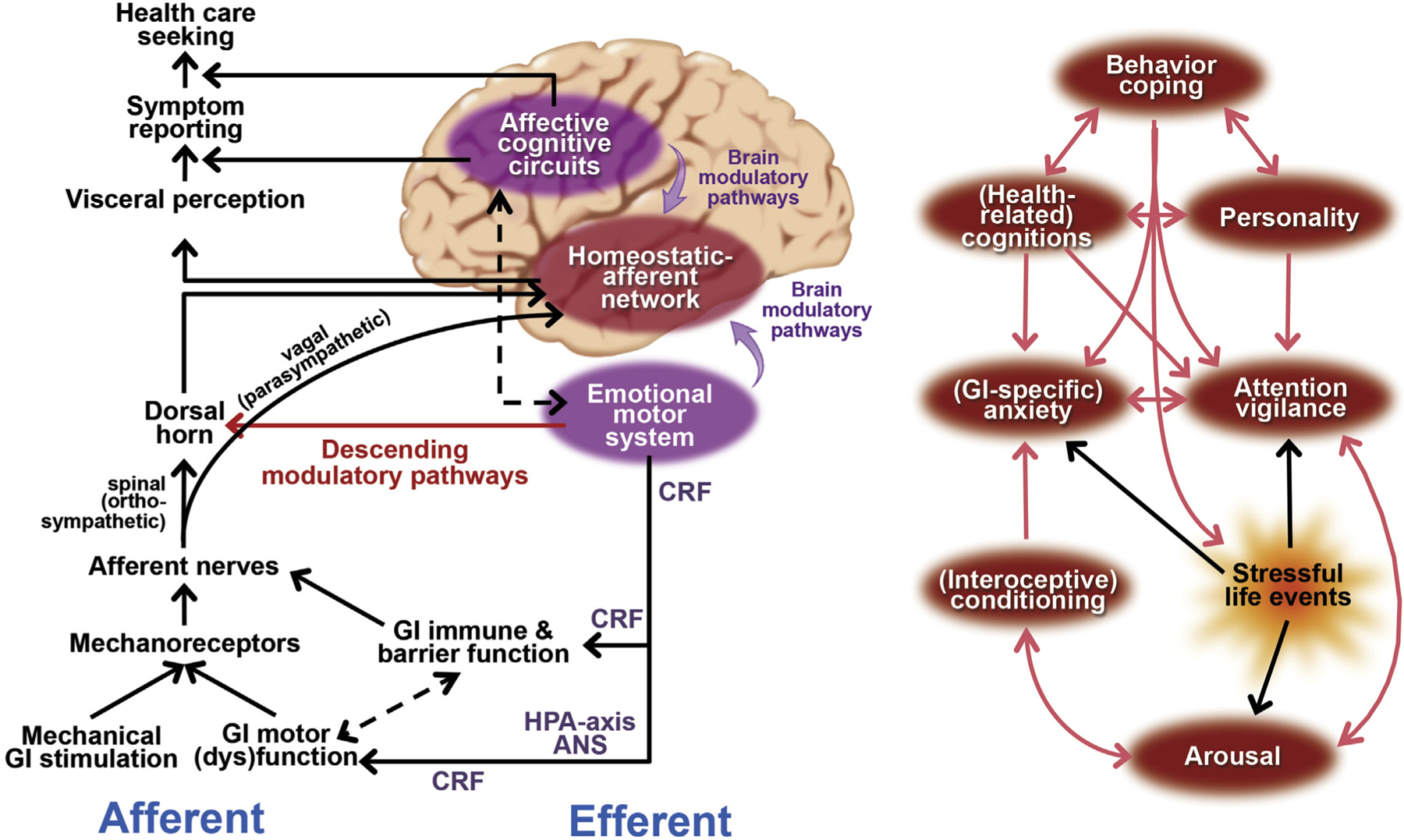

The “brain‒gut axis” is the bidirectional neurohumoral communication system between the brain and the gut that is continuously signaling homeostatic information about the physiological condition of the body to the brain through afferent neural (spinal and vagal) and humoral “gut‒brain” pathways.42 Under normal physiological conditions, most of these interoceptive gut‒brain signals are not consciously perceived. However, the subjective experience of visceral pain results from the conscious perception of salient gut‒brain signals induced by noxious stimuli, which indicate a potential threat to homeostasis, thereby requiring a behavioral response. In the brain, [visceral afferent] interoceptive signals are processed in a homeostatic‒afferent network (brainstem sensory nuclei, thalamus, posterior insula) and integrated with and modulated by emotional‒arousal (locus coeruleus, amygdala, subgenual anterior cingulate‒cortex) and cortical modulatory (prefrontal cortex and anterior insula, perigenual anterior cingulate cortex) neurocircuits. Key regions in these emotional‒arousal and cortical‒modulatory circuits project in a “top-down” fashion to brainstem areas, such as the periaqueductal gray and the rostral ventrolateral medulla, which, in turn, send descending projections to the dorsal horn of the spinal cord, where pain transmission is modulated (descending modulatory system) (Figure 4). Thus, [visceral] pain perception does not display a linear relationship with the intensity of peripheral afferent input, but rather emerges from a complex psychobiological process whereby visceral afferent input is processed and continuously modulated by cognitive and affective circuits at the level of the brain and through descending modulatory pathways. These mechanisms help understand the influence of the cognitive and affective processes outlined in the previous section on GI symptom perception in FGID patients, as well as the therapeutic effect of interventions targeting these processes, and constitute the basis for a model of FGID as disorders of gut‒brain signaling. More specifically, dysfunction of these modulatory systems might allow physiological (non-noxious) stimuli to be perceived as painful or unpleasant (visceral hypersensitivity), which can lead to chronic visceral pain and/or discomfort, hallmark symptoms of FGID. The results of functional brain imaging studies in FGID will be outlined and should be interpreted within this framework.

Figure 4.

Overview of pathways through which psychological processes exert their role in functional gastrointestinal disorders. The “emotional motor system” consists mainly of subcortical and brain stem areas (amygdala, hypothalamus, and periaqueductal gray matter) that are crucial in relaying descending modulatory output from affective and cognitive cortical circuitry, as well as regulating autonomic and HPA axis output. CRF, corticotrophin-releasing factor. Figure adapted from Van Oudenhove and Aziz46 and Naliboff and Rhudy,110 with permission.

Functional gastrointestinal disorders.

Behavioral studies on psychosocial influences on perception of gastrointestinal distension.

The exact nature of the visceral hyperalgesia or hypersensitivity found in a substantial subset of IBS and FD patients remains unclear. The concept of “visceral hypersensitivity” is operationalized as lower pain thresholds during visceral sensory testing, that is, reporting pain at lower pressures or volumes during repeated ascending inflations of a GI balloon catheter. However, as we have outlined, it is becoming increasingly clear that psychological processes and psychosocial factors can influence visceral perceptual sensitivity.

Several studies suggest that an increased psychological tendency to report pain, which can be driven by hypervigilance, underlies the decreased pain thresholds in IBS patients, rather than increased neurosensory sensitivity.43 Studies on the effects of stressors on perception of colorectal distention in healthy subjects and IBS patients have produced somewhat inconsistent findings, due to variations among the stressors used or potential confounders, such as distraction. However, a study that controlled for distraction demonstrated that IBS patients, but not healthy subjects, rated rectal distension more intense and unpleasant during dichotomous listening stress compared with relaxation.44

In addition, anxiety and depression levels are associated with increased pain ratings but not increased rectal sensitivity in IBS.45 Further, several studies have demonstrated a relationship between psychosocial status on the one hand, and gastric discomfort thresholds or symptom reporting in FD on the other.46 In the next section, we will discuss the emerging evidence from functional brain imaging studies clarifying the mechanisms underlying these psychological influences on rectal sensitivity in IBS.

Visceral stimulation studies.

A recent meta-analysis of rectal distension studies demonstrated that IBS patients showed greater brain responses than healthy subjects in homeostatic‒afferent brain regions. Further, IBS patients showed engagement of emotional‒arousal regions that lacked consistent activity in healthy subjects and less involvement of key cortical‒modulatory regions.47 This response pattern is consistent with the increased sympathetic arousal, anxiety, and vigilance often associated with IBS. Similarly, FD patients activate homeostatic‒afferent and sensory brain regions at significantly lower intragastric balloon pressures than healthy controls, with these lower-intensity levels of gastric stimulation, inducing similar levels of perception (gastric hypersensitivity). During painful gastric distension, FD patients did not activate the perigenual anterior cingulate cortex, a key region of the descending modulatory system, and this lack of activation was correlated with anxiety levels.48

A few studies have also examined the brain response to anticipation of a visceral stimulus in both healthy subjects and IBS patients. In IBS patients, the anticipatory response in the locus coeruleus is predictive of both the subjective and brain response to subsequent noxious rectal distention.49 In FD, during anticipated gastric distension, patients fail to deactivate the amygdala, a key emotional arousal region involved in pain modulation, which is paralleled by higher pain ratings during anticipation.48

Taken together, these results are consistent with the model of FGID as disorders of gut‒brain signaling outlined here: anxiety-related impairment of the descending modulatory system causes defective sensory filtering, dependent on which physiological levels of gastric distension are perceived as painful.

Brain networks.

Compared with healthy subjects, IBS patients show up-regulated connectivity within the emotional‒arousal circuitry, and altered serotonergic modulation of this circuitry appears to play a role in visceral hypersensitivity in female IBS patients.50 Additionally, the importance of descending pain modulatory circuitry has been demonstrated in IBS patients and healthy controls.51

Structural imaging.

IBS is associated with decreased gray matter density in cortical‒modulatory prefrontal and parietal regions, as well as in emotional circuits.52 Controlling for anxiety and depression, several of the affective regions no longer differed between IBS patients and controls, whereas the differences in prefrontal and posterior parietal cortices remained. These findings are consistent with the close relationship of IBS to mood disorders. In another study, pain catastrophizing was negatively correlated with degree of cortical thickness in the prefrontal cortex.53 Similarly, gray matter density in sensory and homeostatic‒afferent regions, as well as cortical pain modulatory areas is decreased in FD patients compared with healthy controls, and most of these differences disappear when controlling for anxiety and depression scores.54

It remains unknown whether these changes are pre-existing risk factors for disease or whether they are secondary changes, and what the underlying biological substrates are.

Resting state functional imaging.

Female IBS subjects have greater high-frequency power in the insula and low-frequency power in the sensorimotor cortex than male IBS subjects during task-free rest. Correlations were observed between resting-state activity and IBS symptoms.55 It should be emphasized, however, that these new findings, although interesting, are preliminary. Specifically, it remains to be determined whether these findings are specific to IBS, or a feature of FSS in general, and to what extent these changes are driven by comorbid psychiatric disorders.

In FD, using 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron-emission tomography, increased activity was found in homeostatic‒afferent and sensory regions, but also in the perigenual anterior cingulate cortex, a key pain modulatory area. The activity in the homeostatic‒afferent regions correlated with dyspepsia symptom levels.56 Further, FD patients with comorbid anxiety and depression are characterized by altered activity in homeostatic‒afferent and sensory regions, as well as a number of other regions compared with patients without such comorbidity.57 Using radioligand positron-emission tomography, higher cannabinoid-1 receptor availability was found in FD compared with matched controls, in virtually all of these regions, indicating that altered endocannabinoid function can underlie the differences in resting state brain activity found in FD.58 Several recent resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging studies in FD demonstrated altered functional connectivity at rest, including in the “default mode network”59 (a set of coherent brain processes in medial prefrontal, temporal, and parietal regions that is active during self-referential and reflective activity at rest, without attention being allocated to a particular intero- or exteroceptive stimulus), pain modulatory networks, as well as homeostatic‒afferent circuits. The dysfunctional connectivity patterns correlate with dyspepsia symptom severity, as well as comorbid anxiety and depression levels.60

Taken together, these findings indicate that patients with IBS and FD are not only characterized by abnormal brain responses to visceral pain stimuli, but also by abnormal brain activity and connectivity at rest. These abnormalities seem to be at least partly related to comorbid anxiety and depression.

White matter tract imaging.

IBS patients have white matter tract alterations in multiple areas, including thalamus basal ganglia and sensory/motor association/integration regions compared with healthy controls.61 Another study showed that white matter changes in IBS are related to symptom severity and psychological variables of trait anxiety and catastrophizing.62 Zhou et al63 demonstrated abnormalities in a number of white matter tracts in FD patients vs healthy controls, but again, most of these differences were accounted for by comorbid anxiety and depression.63

Psychosocial influences on gut function through efferent output of central emotional‒arousal circuits.

Brain‒gut interfaces: the autonomic nervous and stress-hormone systems.

In addition to their modulatory influences on the processing of visceral afferent input, psychological processes and distress can influence various aspects of GI function through efferent brain‒gut pathways. More specifically, emotional‒arousal brain circuits control output of the efferent autonomic nervous system (ANS) (ortho/parasympathetic balance) as well as the stress hormone system (hypothalamo‒pituitary‒adrenal [HPA] axis), both of which can alter GI motor, immune, or barrier function, which can in turn influence visceral afferent signaling. The “emotional motor system,” consisting of key subcortical nodes of the emotional‒arousal circuit (hypothalamus, amygdala, and periaqueductal gray) plays a key role in these processes64 (Figure 4). The corticotrophin-releasing factor transmitter system, both centrally (at the level of the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus, hypothalamus, and amygdala) and peripherally (at the level of the GI tract/enteric nervous system), is of major importance here as it influences autonomic outflow as well as stimulates the HPA axis resulting in adrenocorticotropic hormone and cortisol secretion.65

Studies of stress influences on motor, barrier, and immune functions of the gastrointestinal tract.

Gastric motility.

Evidence on the influence of stress on gastric motility is mixed, although most older studies point toward a stress-induced reduction in antral motility and/or gastric emptying.46 More recent studies demonstrated impairment of gastric accommodation during experimentally induced anxiety in healthy subjects,66 as well as an association between both state anxiety and comorbid anxiety disorders and impaired accommodation in FD.58

Colonic motility.

IBS patients show exaggerated motility responses to physical and psychological stress, as well as intravenous injection of corticotrophin-releasing factor.67 A critical role for motility disturbances in producing symptoms, especially pain, in a majority of IBS patients has, however, not been clearly demonstrated, except for stool frequency and consistency,68 abdominal distension, and dissatisfaction with bowel movements.69

Colonic mucosal permeability and low-grade mucosal and systemic inflammation.

A subset of IBS patients (not limited to post-infectious IBS) are characterized by impaired colonic mucosal integrity and low-grade mucosal and even systemic inflammation. These alterations, although not confirmed in all studies, may be related to rectal hyper-sensitivity and pain symptom levels.70 Animal studies have demonstrated the influence of stress on colonic permeability, as well as mucosal and systemic inflammation, mediated by the ANS (eg, the vagal efferent cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway) and HPA axis.71 In humans, indirect evidence comes from studies in IBS linking HPA axis hyperactivity (cross-sectionally) to increased systemic interleukin 6 levels.72 Anxiety and depression levels have been linked to production of tumor necrosis factor‒α and other pro-inflammatory cytokines,73,74 as well as to number of mast cells in the mucosa.75 In addition, psychological morbidity or stressful life events at the moment of acute gastroenteritis predict the development of post-infectious IBS, although this has not been confirmed in all studies.76 Finally, both public speech stress and intravenous injection of corticotrophin-releasing factor increase small intestinal permeability through activating the HPA axis (and/or influencing ANS outflow), in a mast cell-dependent fashion.77

Autonomic nervous system and hypothalamo‒pituitary‒adrenal axis function in functional gastrointestinal disorders.

Autonomic nervous system.

There is only limited support for robust differences in autonomic function measured using cardiovascular (eg, heart rate variability) or circulating (eg, catecholamine) indices of sympathetic and parasympathetic function, both at rest and in response to stress, between patients with FGID and healthy controls. The evidence suffers from limitations, including small sample sizes not allowing conclusions on subgroups or sex differences, inappropriate control of confounders, and reliance on non-GI measures. However, autonomic dysregulation does seem to occur in subgroups of patients and might influence various processes relevant to FGID pathophysiology.78–80

Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis.

Similarly, there is limited evidence for robust alterations in HPA-axis function in FGID, but there are suggestions that some aspects of HPA function might be compromised in some IBS subgroups, especially under stressful conditions.81–85

Microbiome‒Gut‒Brain Axis

The microorganisms in the gut (gut microbiota) engage in bidirectional communication with the brain via neural, endocrine, and immune pathways with significant consequences for behavioral disorders, including anxiety, depression, and cognitive disorders, as well as chronic visceral pain.86 Although much of what is known in this area is based on animal studies, there is also a small, but growing number of relevant human studies. For example, in initial studies, IBS symptoms have been associated with alterations in microbiota composition (although larger studies allowing to control for more potential confounders are clearly needed),87 probiotics have shown promise in treating symptoms in IBS,88 and deficiency in Bifidobacteria has been associated with greater abdominal pain and bloating in a healthy population.89 In addition, administration of a probiotic alters central processing of emotional stimuli, as well as resting brain connectivity in sensory and affective brain circuits.90

Based on these findings, the hypothesis of a microbiome‒gut‒brain axis is emerging, with the possibility that modulation of the gut microbiota may be a target for new therapeutics for stress and pain-related disorders, including FGID.

Psychosocial Assessment

Clinical Assessment

Psychosocial assessment is a critical part of patient care in FGID. As a general rule, primary care clinicians and gastroenterologists should approach psychosocial assessment from a screening perspective with the goal to identify patients at risk for refractory symptoms, poor treatment response or low quality of life. In the absence of frank psychopathology and moderate to severe symptoms, one might also assess visceral-specific anxiety, catastrophizing, somatization, and quality of life to determine whether a comprehensive evaluation by a health psychologist or psychiatrist would be indicated.

We suggest that clinicians include a brief psychosocial assessment of each FGID patient, in addition to a full clinical assessment of the presenting symptoms. This requires a satisfactory patient‒doctor relationship, established during the early part of the consultation, and a few specific questions about key psychosocial processes integrated into routine history taking. If the patient queries the relevance of these questions, the clinician can truthfully respond, “I always ask my patients these questions as part of my initial assessment—it helps me determine the best way to help. The items may or may not apply to you.” This psychosocial assessment will only be satisfactory if the patient is able to speak freely, which requires privacy, a lack of judgment or stigma, and sufficient time. Sensitive areas of discussion include abuse history, depressed mood, possible suicidal thoughts, and the nature of close relationships. Sometime these require a second appointment directed toward this area of assessment. In addition, the clinician should provide feedback about the results of the entire evaluation and to discuss treatment plans, which can involve both medical and psychosocial treatment strategies.

A more detailed psychosocial assessment, preferably by a [health] psychologist, [consultation-liaison] psychiatrist, or specially trained gastroenterologist or other clinician is particularly useful for severe symptoms, previous treatment failure, poor adherence to a treatment regimen, and marked disability. Our recommended assessment and treatment flowchart is also included as Supplementary Table 1A (overview) and 1B (detailed steps) and guidelines and flags for mental health professional involvement are shown in Supplementary Table 2.

Questionnaires can enhance the information obtained at the clinical interview, but not replace it. Further, questionnaires only provide meaningful information if they are reliable (consistent), valid (measure what they are supposed to measure), and free of potential response biases. However, although these psychometric properties have been established in many populations for a given questionnaire, they might not have been tested in specific FGID populations. The clinician should be acquainted with the results and interpretation of such questionnaires and a close working relationship with a mental health professional is helpful in this respect.

Assessment Tools in Adult Patients

An overview of key areas for psychosocial assessment in adult patients is given in Supplementary Table 3. Additional standardized self-report questionnaires are listed in Supplementary Table 4.

Assessment Tools in Children and Their Parents

An overview of key areas for psychosocial assessment in children and their parents is given in Supplementary Table 3. Additional standardized self-report questionnaires are listed in Supplementary Table 4.

Structured Interviews

Details on recommended tools for assessment of the different psychosocial domains outlined earlier are provided in the Supplementary Material.

Treatment

Psychological Treatments

Rooted in the biopsychosocial model of FGID and its biological basis outlined earlier, psychological treatments hold that biological factors work in concert with psychological and social variables to influence the expression of symptoms and their impact on other health outcomes (eg, quality of life and health care use). As such, psychological treatments aim to tackle the environmental and psychological processes that aggravate symptoms. The most commonly studied psychological treatments for FGID are CBT, psychodynamic psychotherapy, and hypnosis. A brief overview is given in Supplementary Table 4.

Cognitive-behavior therapy.

CBT refers to a family of psychological treatments rather than a specific or uniform set of techniques. The rationale and techniques of CBT draw from behavior theories that emphasize learning processes and cognitive theory that emphasizes faulty cognitions or thinking processes. These same learning processes can be used to help patients gain control and reduce symptoms of FGID.91 Cognitive theory views external events, cognitions, and behavior as interactive and reciprocally related. As such, each component is capable of affecting the others, but the primary emphasis is the way patients process information about their environment. Cognitive factors, especially the way people interpret or think about stressful events, can intensify the impact of events on responses beyond the impact of events themselves (Figure 3). To the extent that thinking processes are faulty, exaggerated, and biased, patients’ emotional, physiological, and behavioral responses to life events will be problematic. Clinically, this means that modifying their thinking styles can change the way patients behave and feel both emotionally and physically. These cognitive changes can occur by teaching patients to systematically identify cognitive errors or faulty logic brought about by automatic thinking or providing experiential learning opportunities that systematically exposes patients to the situations that cause discomfort.

Rather than focusing on the root causes of a problem, like traditional “talk therapy,” CBT focuses on teaching people how to control their current difficulties and what is maintaining them. Further, because CBT is a more directive therapy, the therapist plays a more active role. CBT requires active participation of the patient both during and between sessions, as well as responsibility for learning symptom self-management skills. In addition, CBT is more problem-focused, goal-directed, and time-limited (3‒12 hourly sessions). In the case of FGID, CBT includes a combination of techniques including self-monitoring, cognitive restructuring, problem solving, exposure, and relaxation methods.

Self-monitoring.

Self-monitoring is the ongoing, real-time recording of problem behaviors. In CBT for IBS, self-monitoring focuses on internal and external triggers, as well as thoughts, somatic sensations, and feelings that typically accompany flareups. In addition to providing a rich source of clinically relevant information to structure treatment, self-monitoring comprises a useful therapeutic strategy because it increases awareness of the determinants of a patient’s problem.

Cognitive strategies.

Cognitive strategies are designed to modify thinking errors that bias information processing. Examples include a tendency to overestimate risk and the magnitude of threat, or underestimate one’s own ability to cope with adversity if it were to occur.40 These self-defeating beliefs are clinically important because they are believed to moderate excessive stress experiences. Once these negative beliefs are identified, the patient works with the therapist to challenge and dispute them by examining their accuracy in light of available evidence for and against them, and replacing these beliefs with those that are more logical and constructive.

Problem-solving.

Problem-solving refers to an ability to define problems, identify solutions, and verify their effectiveness once implemented.92 As an intervention, it is rooted in a problem-solving model of stress93 that emphasizes the causal relationship between how people problem solve around stressors and their health. Therapists teach patients how to effectively apply the steps of problem solving, including identifying problems, generating multiple alternative solutions (“brainstorming”), selecting the best solution from the alternatives, developing and implementing a plan, and evaluating the efficacy.

Relaxation procedures.

Relaxation procedures have long been a staple of psychological treatments for FGID94 and are designed to directly modify the biological processes (eg, autonomic arousal) that are believed to aggravate GI symptoms.

Progressive muscle relaxation training consists of systematic tensing and relaxing selected muscle groups of the whole body; it presumably helps patients dampen physiological arousal and achieve a sense of mastery of physiological self-control over previously uncontrollable and unpredictable symptoms.95

In breathing retraining, the patient is taught to take slow deep breaths and attend to relaxing sensations during exhalation. This relaxation procedure is based on the assumption96 that patients with stress-related physical ailments develop inefficient respiratory patterns (eg, shallow chest breathing) which, if chronic, can intensify physiological arousal that aggravates somatic complaints.

Meditation is a self-directed practice that emphasizes focused breathing, selective attention to a specially chosen word, set of words, or object, and detachment from thought processes to achieve a state of calmness, physical relaxation, and psychological balance. One type of meditation featured in the FGID literature is mindfulness meditation,97 where an individual disengages him/herself from ruminative thoughts, which are regarded as core aspects of pain and suffering, by developing a nonreactive, objective, present-focused approach to internal experiences and external events as they occur.98

Hypnosis.

In hypnosis,99 a therapist typically induces a trance-like state of deep relaxation and/or concentration using strategically worded verbal cues suggestive of changes in sensations, perceptions, thoughts, or behavior. Most hypnotic suggestions are designed to elicit feelings of improved relaxation, calmness, and well-being. In the context of IBS, hypnotic suggestions are “gut directed,” that is, the therapists convey suggestions for imaginative experiences incompatible with aversive visceral sensation. Hypnosis for a patient with IBS might include a suggestion that the patient feel a sense of warmth and comfort spreading around the abdominal area.

Exposure.

Exposure treatments are designed to reduce catastrophic beliefs about IBS symptoms, hyper-vigilance to IBS symptoms, fear of IBS symptoms, and excessive avoidance of unpleasant visceral sensations or situations100 by helping patients confront them in a systematic manner. Exposure can include interoceptive cue exposure in which the patient repeatedly provokes unpleasant sensations, or situational or in vivo exposure in which feared situations or activities are confronted. The basic idea behind exposure interventions is that the most effective way to overcome a fear is by facing it head on so that the natural conditioning (learning) processes involved in fear reduction (habituation and extinction) can occur. Without therapeutic assistance, the individual withdraws from fear-inducing situations, thereby inadvertently reinforcing avoidance. Through exposure treatments, patients learn that the stimuli that are a source of fear and avoidance are neither dangerous nor intolerable and that fear will subside without resorting to avoidance, a behavior that reinforces fear and hypervigilance in the long-term.101

Efficacy of psychological treatments. Two meta-analyses102,103 have concluded that psychological therapies, as a class of treatments, are at least moderately effective for relieving symptoms of IBS when compared with a pooled group of control conditions. One measure of clinical efficacy is the numbers needed to treat, referring to the number of patients needed to be treated to achieve a specific outcome, such as a 50% reduction in GI symptoms. Numbers needed to treat of 2 and 4 were found in both meta-analyses. Ljótsson and colleagues104 have used the Internet as a platform for delivering treatment to a larger proportion of FGID patients than would have had access to clinic-based treatments.

Is the Patient a Good Candidate for Psychological Treatments?

Characteristics to guide decision making about which patients are likely to benefit from psychological treatments are provided in the Supplementary Material.

Pharmacological Treatment.

We recognize and have acknowledged that there is limited evidence from randomized controlled trials in gastroenterology for some of the agents discussed here. However, we have relied on evidence-based data from other related pain disorders, as well as on the consensus of experts in this field to provide their best current recommendations for practice.

Mechanism of action of centrally acting agents in functional gastrointestinal disorder.

There are several (not mutually exclusive) putative mechanisms of action explaining the therapeutic effects of antidepressants and other centrally acting agents in the treatment of FGID in adults, including effects on gut and/or ANS physiology, and central analgesic effects, which may or may not be independent of anxiolytic and antidepressant effects.

Further details on the mechanisms of action of psychotropic drugs in FGID are also described elsewhere in this issue.

Clinical considerations for the use of psychotropic medications in functional gastrointestinal disorders.

Although antidepressants are used extensively, they are still considered “off label” for their use in FGID. The accumulated clinical experience, lack of other effective treatment options, and evidence from other FSS, such as fibromyalgia, make them viable options for treating pain and improving quality of life in FGID. In general, they should be reserved for patients with moderate to severe disease severity, with significant impairment of quality of life, and where other first-line treatments have not been sufficiently effective.

Choice of agent.

Choice of agent is determined by the patient’s predominant symptoms, disease severity, presence of comorbid anxiety or depression, prior experience with medications in the same class, and patient and prescriber preference.

In general, tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) are the first choice for pain in nonconstipated IBS patients due to their dual mechanism of action (serotonin and noradrenalin reuptake inhibition). Nortriptyline or desipramine is generally better tolerated than amitriptyline or imipramine due to less anti-histaminergic and anti-cholinergic effects. The usual starting dose is 25‒50 mg at night and can be titrated up as needed up to about 150 mg/d, while carefully monitoring side effects and/or blood levels, although typically lower doses than the full antidepressant dose are effective for visceral pain if no psychiatric comorbidity is present. Because selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are less effective for pain, they are not commonly used as monotherapy. Rather, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are a useful augmentation agent in combination with other drugs, such as serotonin noradrenalin reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) or TCAs, or when the patient has a high level of anxiety that is contributing directly to their clinical presentation. The selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and SNRIs have a more narrow therapeutic range and therefore the doses used for the treatment of pain are closer to the doses used to treat mood and anxiety disorders.105 Starting doses are usually within the lower range of the psychiatric dose (eg, citalopram 20 mg or duloxetine 30 mg) and titrated up as needed. For SNRIs, especially venlafaxine, the analgesic effect usually requires higher doses (≥225 mg) because the noradrenergic mechanism of action only kicks in at these doses. If nausea and weight loss are of concern, the addition of a low dose (15‒30 mg) of mirtazapine can be helpful. Atypical antipsychotics, such as quetiapine, are only recommended for patients with severe, refractory IBS, especially if severe anxiety and sleep disturbances are also present and patients have failed to respond to other centrally acting agents. A low starting dose of 25‒50 mg is recommended and can be titrated up as required.106,107

Augmentation.

Augmentation, that is, the use of a combination of drugs from different classes in submaximal doses instead of one drug at a maximal dose, is common in psychiatry and increasingly used in FGID. Examples of augmentation include adding buspirone to an selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, TCA, or SNRI to enhance their therapeutic effect, or adding a low-dose antipsychotic (eg, quetiapine) to a TCA or SNRI to reduce pain and anxiety and improve sleep.106 If there is a component of abdominal wall pain associated with the GI pain, pregabalin or gabapentin can be added to a TCA or SNRI.106

Adherence.

Careful patient selection, initiation at a low dose with gradual escalation, monitoring for side effects, and a good patient‒doctor relationship are important for medication adherence and, therefore, therapeutic response. In particular, eliciting and addressing any potential concerns/barriers to taking psychotropic medications for FGID, discussing potential side effects, setting realistic expectations, and involving the patient in decision making result in improved adherence.107

Centrally acting agents and psychological treatments.

Centrally acting agents and psychological treatments are often used together for their complementary and synergistic effects; such combination is recommended when the FGID is severe and associated with anxiety or depression comorbidity.106

Although drugs work faster and are readily available, psychological treatments have several advantages: they are safe, effective, their effects persist beyond the duration of the treatment, and they may be more cost-effective.108 Limitations of using psychological treatments are longer treatment duration and need for patient motivation, as well as availability and access to a mental health professional trained in FGID treatment.

Conclusions

In this article, we provided a comprehensive overview of recent research to improve understanding of the complex interactive biopsychosocial processes that constitute the pathophysiology of FGID. In addition, we outlined the clinical tools and practices health care practitioners can utilize to improve assessment and treatment of these disorders. Further research is needed to expand this knowledge base, which will foster the development of novel, more efficacious treatments that are more efficiently delivered as well as better tailored to individual patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Jerry Schoendorf for his help with making and adapting the figures.

Abbreviations used in this paper:

- ANS

autonomic nervous system

- CBT

cognitive-behavioral treatment

- FD

functional dyspepsia

- FGID

functional gastrointestinal disorder

- FSS

functional somatic syndromes

- GI

gastrointestinal

- HPA

hypothalamo‒pituitary‒adrenal

- IBS

irritable bowel syndrome

- SNRI

serotonin noradrenalin reuptake inhibitor

- TCA

tricyclic antidepressant

Footnotes

Supplementary Material

Note: The first 50 references associated with this article are available below in print. The remaining references accompanying this article are available online only with the electronic version of the article. To access the supplementary material accompanying this article, visit the online version of Gastroenterology at www.gastrojournal.org, and at http://dx.doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.027.

Conflicts of interest

These authors disclose the following: Albena Halpert is on the advisory board of Allergan; Michael Crowell is a consultant for Medtronic-Covidien and Salix. The remaining authors disclose no conflicts.

References

- 1.Bode G, Brenner H, Adler G, Rothenbacher D. Recurrent abdominal pain in children: evidence from a population-based study that social and familial factors play a major role but not Helicobacter pylori infection. J Psychosom Res 2003;54:417–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levy RL, Whitehead WE, Von Korff MR, et al. Intergenerational transmission of gastrointestinal illness behavior. Am J Gastroenterol 2000;95:451–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walker LS, Garber J, Greene JW. Somatization symptoms in pediatric abdominal pain patients: Relation to chronicity of abdominal pain and parent somatization. J Abnorm Child Psychol 1991;19:379–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walker LS, Garber J, Greene JW. Somatic complaints in pediatric patients: a prospective study of the role of negative life events, child social and academic competence, and parental somatic symptoms. J Consult Clin Psychol 1994;62:1213–1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levy RL, Jones KR, Whitehead WE, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome in twins: Heredity and social learning both contribute to etiology. Gastroenterology 2001; 121:799–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levy RL, Whitehead WE, Walker LS, et al. Increased somatic complaints and health-care utilization in children: effects of parent IBS status and parent response to gastrointestinal symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol 2004; 99:2442–2451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walker LS, Williams SE, Smith CA, et al. Parent attention versus distraction: impact on symptom complaints by children with and without chronic functional abdominal pain. Pain 2006;122:43–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levy RL, Langer S, Walker L, et al. Twelve month follow-up of cognitive behavioral therapy for children with functional abdominal pain. JAMA Pediatr 2013; 167:178–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levy RL, Langer SL, Romano JM, et al. Cognitive mediators of treatment outcomes in pediatric functional abdominal pain. Clin J Pain 2014;30:1033–1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seino S, Watanabe S, Ito N, et al. Enhanced auditory brainstem response and parental bonding style in children with gastrointestinal symptoms. PLoS One 2012; 7:e32913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Campo JV, Bridge J, Lucas A, et al. Physical and emotional health of mothers of youth with functional abdominal pain. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2007; 161:131–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Langer SL, Romano JM, Levy RL, et al. Catastrophizing and parental response to child symptom complaints. Child Health Care 2009;38:169–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bradford K, Shih W, Videlock EJ, et al. Association between early adverse life events and irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012;10:385–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Drossman DA. Abuse, trauma, and GI illness: is there a link? Am J Gastroenterol 2011;106:14–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Galli N The influence of cultural heritage on the health status of Puerto Ricans. J Sch Health 1975;45:10–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Quigley EM, Sperber AD, Drossman DA. WGO—Rome foundation joint symposium summary: IBS—the global perspective. J Clin Gastroenterol 2011;45:i–ii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murray CD, Flynn J, Ratcliffe L, et al. Effect of acute physical and psychological stress on gut autonomic innervation in iritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2004;127:1695–1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bitton A, Dobkin PL, Edwardes MD, et al. Predicting relapse in Crohn’s disease: a biopsychosocial model. Gut 2008;57:1386–1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lackner JM, Gurtman MB. Pain catastrophizing and interpersonal problems: a circumplex analysis of the communal coping model. Pain 2004;110:597–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sperber AD, Drossman DA, Quigley E. The global perspective on irritable bowel syndrome: a Rome Foundation-World Gastroenterology Organization symposium. Am J Gastroenterol 2012;107:1602–1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Drossman DA, Li Z, Leserman J, et al. Effects of coping on health outcome among female patients with gastro-intestinal disorders. Psychosom Med 2000;62:309–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bennett EJ, Tennant CC, Piesse C, et al. Level of chronic life stress predicts clinical outcome in irritable bowel syndrome. Gut 1998;43:256–261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lackner JM, Gudleski GD, Firth R, et al. Negative aspects of close relationships are more strongly associated than supportive personal relationships with illness burden of irritable bowel syndrome. J Psychosom Res 2013;74:493–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jakobsson Ung E, Ringstrom G, Sjovall H, et al. How patients with long-term experience of living with irritable bowel syndrome manage illness in daily life: a qualitative study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013;25:1478–1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lackner JM, Brasel AM, Quigley BM, et al. The ties that bind: perceived social support, stress, and IBS in severely affected patients. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2010;22:893–900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Conboy LA, Macklin E, Kelley J, et al. Which patients improve: characteristics increasing sensitivity to a supportive patient-practitioner relationship. Soc Sci Med 2010;70:479–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Addolorato G, Mirijello A, D’Angelo C, et al. State and trait anxiety and depression in patients affected by gastrointestinal diseases: psychometric evaluation of 1641 patients referred to an internal medicine outpatient setting. Int J Clin Pract 2008;62:1063–1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bouchoucha M, Hejnar M, Devroede G, et al. Anxiety and depression as markers of multiplicity of sites of functional gastrointestinal disorders: a gender issue? Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol 2013;37:422–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van Oudenhove L, Vandenberghe J, Vos R, et al. Factors associated with co-morbid irritable bowel syndrome and chronic fatigue-like symptoms in functional dypepsia. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2011;23:524–e202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller V, Hopkins L, Whorwell PJ. Suicidal ideation in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004;2:1064–1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lackner JM, Gurtman MB. Patterns of interpersonal problems in irritable bowel syndrome patients: a circumplex analysis. J Psychosom Res 2005;58:523–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lipowski ZJ. Somatization: the concept and its clinical application. Am J Psychiatry 1988;145:1358–1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dimsdale JE, Creed F, Escobar J, et al. Somatic symptom disorder: an important change in DSM. J Psychosom Res 2013;75:223–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Duddu V, Isaac MK, Chaturvedi SK. Somatization, somatosensory amplification, attribution styles and illness behaviour: a review. Int Rev Psychiatry 2006; 18:25–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Van Oudenhove L, Vandenberghe J, Geeraerts B, et al. Determinants of symptoms in functional dyspepsia: gastric sensorimotor function, psychosocial factors, or somatization? Gut 2008;57:1666–1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Van Oudenhove L, Vandenberghe J, Vos R, et al. Abuse history, depression, and somatization are associated with gastric sensitivity and gastric emptying in functional dyspepsia. Psychosom Med 2011;73:648–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Agosti V, Quitkin FM, Stewart JW, et al. Somatization as a predictor of medication discontinuation due to adverse events. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2002;17:311–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Whitehead WE, Palsson OS, Levy RR, et al. Comorbidity in irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol 2007; 102:2767–2776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lackner JM, Ma CX, Keefer L, et al. Type, rather than number, of mental and physical comorbidities increases the severity of symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013;11:1147–1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chilcot J, Moss-Morris R. Changes in illness-related cognitions rather than distress mediate improvements in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) symptoms and disability following a brief cognitive behavioural therapy intervention. Behav Res Ther 2013;51:690–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mayer EA, Tillisch K. The brain-gut axis in abdominal pain syndromes. Annu Rev Med 2011;62:381–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dorn SD, Palsson OS, Thiwan SIM, et al. Increased colonic pain sensitivity in irritable bowel syndrome is the result of an increased tendency to report pain rather than increased neurosensory sensitivity. Gut 2007;56: 1202–1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dickhaus B, Mayer EA, Firooz N, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome patients show enhanced modulation of visceral perception by auditory stress. Am J Gastroenterol 2003;98:135–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Elsenbruch S, Rosenberger C, Enck P, et al. Affective disturbances modulate the neural processing of visceral pain stimuli in irritable bowel syndrome: an fMRI study. Gut 2010;59:489–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Van Oudenhove L, Aziz Q. The role of psychosocial factors and psychiatric disorders in functional dyspepsia. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013; 10:158–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tillisch K, Mayer EA, Labus JS. Quantitative meta-analysis identifies brain regions activated during rectal distension in irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2011;140:91–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Van Oudenhove L, Labus J, Dupont P, et al. Altered brain network connectivity associated with increased perceptual response to aversive gastric distension and its expectation in functional dyspepsia. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2010;22:20–21. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Berman SM, Naliboff BD, Suyenobu B, et al. Reduced brainstem inhibition during anticipated pelvic visceral pain correlates with enhanced brain response to the visceral stimulus in women with irritable bowel syndrome. J Neurosci 2008;28:349–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Labus JS, Mayer EA, Jarcho J, et al. Acute tryptophan depletion alters the effective connectivity of emotional arousal circuitry during visceral stimuli in healthy women. Gut 2011;60:1196–1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.