Abstract

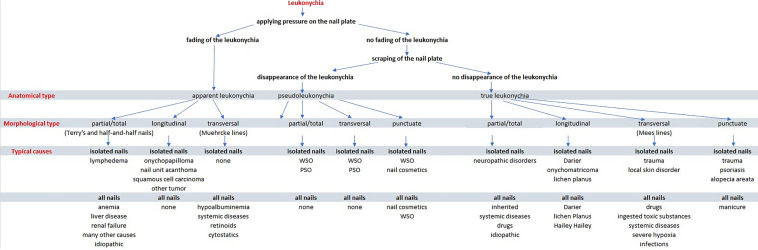

Changes in nail color can provide important clues of underlying systemic and skin disease. In particular, white discoloration (leukonychia) has a high prevalence with a wide array of potential relevant causes, from simple manicure habits to life-threatening liver or kidney failure. Therefore, a reliable assessment of the patient with leukonychia is essential. In the past, two classifications for leukonychia have been presented. The morphological classifies the nail according to the distribution of the white lines: total, partial, transversal, and longitudinal leukonychia. Mees’ and Muehrcke’s lines are examples of transversal leukonychia, while Terry’s and Lindsay’s nails are examples of total and partial leukonychia. The anatomical classifies according to the structure responsible for the white color: the nail plate in true leukonychia, the nail bed in apparent leukonychia, and the surface only in pseudoleukonychia. In this review, both morphological and anatomical features have been combined in an algorithm that enables clinicians to approach leukonychia efficiently and effectively.

Key Points

| Leukonychia, or white nails, is usually not an alarming sign, but it can sometimes unmask severe systemic disorders or congenital conditions. |

| It is difficult, but essential, to identify the underlying cause of leukonychia in individual patients. Morphological and anatomical classifications have been introduced in the past. In this review, a comprehensive algorithm is introduced to facilitate the identification of the underlying cause of the white nails. |

Introduction

Leukonychia, or white nails, is usually not an alarming sign, but it can sometimes unmask severe systemic disorders or congenital conditions. The white color can be due to nail plate or nail bed abnormalities. Differentiating between these two is essential in the classification and interpretation of leukonychia. The aim of this article is to guide clinical practice by reviewing data concerning several types of leukonychia, with particular reference to all clinical and dermoscopic features, associated medical conditions, pathogenesis, and necessary work-up.

Classification

In 1896, Unna classified leukonychia into three morphologic presentations: total, striate (transversal and longitudinal), and punctate. A fourth presentation was added few years later, which Weber called leukonychia partialis for nails that were incompletely white [1]. Besides the morphological classification, leukonychia can be divided into three anatomical types [2]: true leukonychia due to intrinsic matrix and plate abnormalities, apparent leukonychia, which occurs when the pathology involves subungual tissues, and pseudo-leukonychia describing whiteness of the superficial (dorsal or ventral) nail plate. While the morphological types are obvious, the anatomical types need simple tests to be differentiated: in true leukonychia, being the abnormality within the plate, there is no fading of the color with its pressure and the same is for pseudoleukonychia, which is due to external factors responsible for superficial nail plate scaling. Apparent leukonychia instead, being an abnormality of the nail bed, fades with pressure because pressure results in a temporary reduction of nail bed edema and then better visibility of nail bed vessels. The last test is the moving of the white color with nail plate growth: it moves distally with the plate growth in true and pseudoleukonychia, but it stays there in apparent leukonychia.

All forms can be temporary or permanent, monodactylous or polydactylous. Obviously, monodactylous leukonychia most likely is caused by local factors involving that digit, while polydactylous indicates a systemic factor.

Pathophysiology

Newton’s theorem states that a surface appears white when it reflects all the radiation of visible light. The nail plate surface in true leukonychia looks white because it reflects visible light in a diffuse way preventing the visualization of the underlying vascularized nail bed. This is due to an abnormal distal matrix keratinization [3], resulting in persistent and odd-appearing parakeratosis with disorganized large and globular onychocytes with perinuclear vacuolization [4] and keratohyaline granules in intermediate and ventral nail plates [5, 6]. Under the electron microscope, the keratin fibers are also dissociated, fragmented, and irregularly aligned [7, 8]. Parakeratosis can be induced by numerous factors damaging the distal nail matrix. Once the trigger stops or is removed (when feasible), the white color starts to grow out. The white color in apparent leukonychia is instead the result of blood vessel compression of the nail bed. Histologically, the white area is considered to be caused by chronic anemia secondary to increased wall thickness of capillaries, by modification of subungual keratin, or by overgrowth of connective tissue between the nail and the bone with the reduction of blood in the subpapillary plexus. Localized or general edema of the nail bed is one of the possible factors that induces compression and constriction of subungual vasculature and affects the organization of the collagen fibers of the nail bed. The role of edema is also suggested by a higher prevalence of apparent leukonychia in the involved limb in unilateral lymphoedema [9]. Once the causative factor is eliminated, resolution starts distally and moves proximally, the opposite from what happens in true leukonychia. This is explained by the assumption that the capillary filling of the nail bed runs from distal to proximal. The capillary blood pressure may be slightly higher distally (close to the afferent arterioles) than proximally (close to the efferent venules). In the case of a reduction in the nail bed edema, distally, this resistance can be overcome easier because of the slightly higher capillary blood pressure and this results in the disappearance of the whitish area first.

In ‘half-and-half nails’, there is a reddish-brown distal band, and this was believed to be due to melanin pigmentation within the distal plate. Leyden and Wood suggested that the renal decompensation may account for the stimulation of matrix melanocytes and subsequent pigment formation and deposition [10]. This position within the nail plate is remarkable because the distal band does not grow out, but remains at the distal site of the nail. Bencini et al. instead regarded the nail color change as part of the diffuse skin hyperpigmentation observed in patients with chronic renal failure and attributed to the poorly dialyzable, high tissue level of β-melanin-stimulating hormone [11]. This finding appears strange because Leyden and Wood did not find melanocytes in the nail bed near the reddish-brown band, and the number of melanocytes in the nail bed is now known to be much lower than in the nail matrix [12, 13]. The proximal part appears white because the nail plate may have a looser attachment to the nail bed in this area. In Terry’s nails, there is also reddish-brown distal band that is narrower compared with half-and-half nails. It has been suggested to be an area of telangiectasia, but this has never been confirmed and telangiectasias are not visible at dermoscopy. Other hypotheses have been advanced, such as an abnormal ratio of estrogen to androgens or an abnormal steroid metabolism. However, there are embryological and anatomical reasons to suspect that the proximal and distal nail beds have two separate blood supplies: we speculate that the telangiectasias causing Terry’s nails may be related to the underlying mechanism that produces the other vascular changes noted.

In pseudoleukonychia, the transparency of the normal nail plate is impaired by an external factor that destroys the normal tight attachment of the nail plate onychocytes. The upper layers of the nail plate start to scale, resulting in the reflection of light. This form is differentiated from other causes of leukonychia, as the white powdery material can be easily scraped from the affected plate.

Clinical Presentations

Different morphological aspects of leukonychia can coexist in the same digit and in different digits of the same patient. Leukonychia is always asymptomatic and can even go unnoticed.

Punctate Leukonychia (Table 1)

Table 1.

Punctate leukonychia

| True leukonychia | |

| Traumatic | Cryotherapy for the treatment of periungual warts, over-zealous manicure [17, 18], nail biting [18, 19], traumatic event of proximal nail fold [20] |

| Neurovascular disorder | Reflex sympathetic dystrophy [21], epilepsy [22] |

| Skin disease | Psoriasis [18], alopecia areata [14, 18, 23], lichen planus [24], mycosis fungoides [25], vitiligo [26] |

| Deficiency | Zinc [27] |

| Others | Renal transplant recipient [28] |

| Apparent leukonychia | Not existent |

| Pseudoleukonychia | |

| Exogeneous compound | 2-Ethyl-cyanoacrylate glue [29], granulation |

| Skin disease | White superficial onychomycosis [30, 31], proximal subungual onychomycosis |

| Traumatic | |

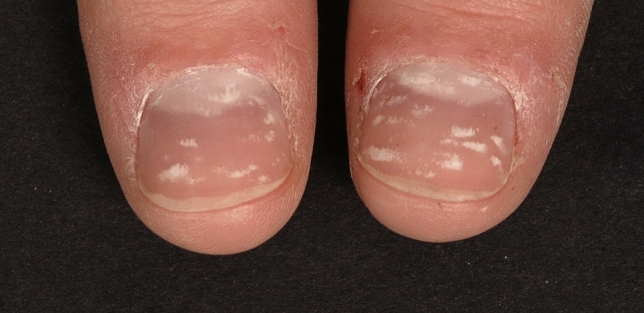

Punctate true leukonychia is probably the most common clinical presentation of leukonychia, especially in children. Not all nail plates are necessarily affected, and every nail plate may be affected in different ways. The pattern and number of spots may change as the nail grows. It is not related to reduced calcium or iron content of the nail plate, as popularly believed. Usually, it is due to trauma (Fig. 1), but it may also be due to inflammatory diseases such as alopecia areata or psoriasis [14–16].

Fig. 1.

Trauma-induced punctate true leukonychia

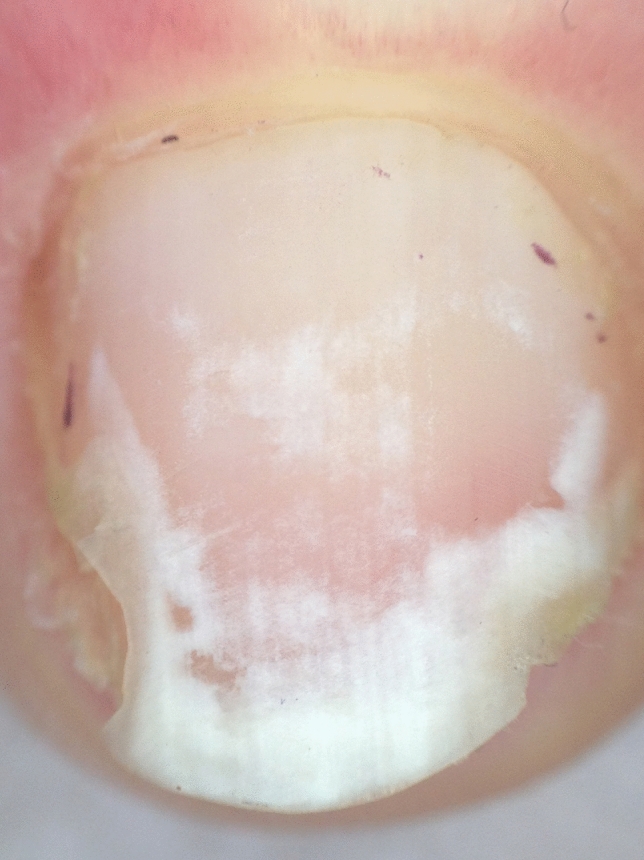

Pseudo-leukonychia also often presents as punctate leukonychia. Typical causes are superficial white onychomycosis (Fig. 2) [30] and nail fragility due to nail cosmetics (Figs. 3, 4). Punctate areas of leukonychia due to fungal invasion can eventually coalesce to involve the entire surface of the nail plate or may present with a single or multiple transversal leukonychial bands separated by a normal nail plate [32, 33]. Artificial nails and frequent use of polish removers damage the superficial layers of the nail plate causing dehydration of the nail keratins that clinically appear as fine and scaling white spots (keratin granulation) [34]. The use of cyanoacrylate glue should also be excluded.

Fig. 2.

Pseudoleukonychia caused by superficial white onychomycosis

Fig. 3.

Pseudoleukonychia and nail fragility induced by nail cosmetics

Fig. 4.

Punctate pseudoleukonychia caused by nail cosmetics (granulation)

Transverse Leukonychia (Table 2)

Table 2.

Transverse leukonychia

| True leukonychia | |

| Traumatic | Repeated trauma to the matrix by pressure on the free edge of the nail plate when the nail is not cut short [4, 38, 39], picking away chipped nail polish [40] |

| Hematologic disorder | Acute myeloid leukemia [41], Hodgkin’s disease, sickle cell anemia |

| Neurovascular disorder | Spinal cord injury [42], epilepsy [22] |

| Skin disease | Psoriasis [18], acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau [18], infection of proximal nail fold, erythema multiforme [43], pellagra [44] |

| Toxic |

Arsenic (Mees’ lines) [35, 45–50], strontium-contaminated water [51], thallium [52, 53] Direct contact with the nail unit: herbicides: paraquat [54, 55], diquat [54, 56], dinitro-orthocresol [57] |

| Drugs | Ciclosporine [58], cytostatics (many) [59, 60], synthetic opioid MT-45 [61], retinoids (acitretin, etretinate, isotretinoin) [62–64], sulfonamide [65], pilocarpine [65] |

| Hormonal | Menstrual cycle [66] |

| Infectious |

Bacterial: pleural empyema [67, 68], acute pulmonary tuberculosis in human immunodeficiency virus [68] Viral: COVID-19 [69, 70], Kawasaki disease [71], herpes zoster [72] Parasitic [73] |

| Systemic disease | Systemic lupus erythematosus [74], chronic kidney disease [75, 76], acute rejection of a renal allograft [77], congestive heart failure [78] |

| Environmental | High altitude [79–81] |

| Apparent leukonychia | (Muehrcke’s lines) |

| Systemic diseases | Hypoalbuminemia [82, 83], kidney transplants [84], patients with chronic renal failure undergoing hemodialysis [76], active rheumatoid arthritis [85], heart transplantation [86, 87], left ventricular assist device [88] |

| Drugs |

Retinoids: acitretin [89], transretinoic acid [90] Cytostatics: cyclophosphamide, adriamycin, and vincristine [91], 5-fluorouracil plus leucovorin [92], cyclophosphamide/doxorubicin/5-fluorouracil [93], 5-fluorouracil/adriamycin/cyclophosphamide [94] |

| Pseudoleukonychia | |

| Skin disease |

Onycholysis Proximal subungual onychomycosis [30, 33, 95], white superficial onychomycosis [30] |

In 1919, Mees reported pale transverse, 1–2 mm wide bands of true leukonychia appearing in the proximal part of the nail plate, and running parallel to the lunula, in patients experiencing arsenic poisoning [35]. While multiple lines may be due to multiple episodes of arsenic ingestion, an alternate theory suggests that they do not necessarily reflect the number of episodes of ingestion. The serial form of deposition may be band-like precipitations of arsenic due to alternate diffusion and nucleation of relatively concentrated arsenic within the nail matrices (Liesegang’s phenomenon) [36]. The lines can present as a retrospective indicator of a pathologic state because their onset is correlated with a systemic insult: fingernails grow about 1 mm every 6–10 days and the bands take some weeks to manifest. In acute arsenic poisoning, it has been claimed that the lines usually appear considerably later, after 40–60 days [37]. This discrepancy has been explained by the assumption that arsenic leukonychia is caused by the precipitation of arsenic and not by damage to the nail matrix [36].

Often described with its eponym Mees’ lines, the bands may have other causes. To be more appropriate with the definition, the white lines should be defined in these cases as trauma-induced transverse true leukonychia. When only the fingernails are affected, manicure mistakes are the possible culprits (Fig. 5) [38]. When the toenails are affected, bands may result from pressure on the free edge of the nail plate not trimmed short (Fig. 6) [4]. Among traumatic etiologies, cryotherapy of warts on the proximal nail fold should also be mentioned but also direct occupational contact with aggressive substances such as concentrated chemicals [54]. A single transversal band may be induced by one relevant trauma or skin diseases of the proximal nail fold [20]. When both fingernails and toenails are affected, a systemic cause should be ruled out: a matrix-toxic substance such as thallium [52], strontium [51], and arsenic, for instance, but chemotherapeutic drugs are the therapeutic agents most frequently involved [96]. No specific drug, combination of drugs, or drug class is responsible [97] but cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and vincristine are those most frequently involved [98]. Additionally, nutritional deficiencies or systemic diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus may provoke transverse true leukonychia (Fig. 7) [74, 99], hematologic disorders, neurovascular disorders, empyema, heart failure, severe hypocalcemia, and systemic infections, including COVID-19 [69, 70]. Occasionally transverse bands are reported to be the result of climbing at high altitude (Everest nails) [79] due to severe hypoxia and catabolic stress and to the combined use of drugs for the prevention and therapy of acute mountain sickness such as acetazolamide and naproxen [100].

Fig. 5.

Transversal true leukonychia caused by traumatic manicure.

Fig. 6.

Trauma-induced transversal true leukonychia caused by matrix damage due to axial pressure on too long toenails

Fig. 7.

Systemic lupus erythematosus-induced transversal true leukonychia

As stated, when the bands fade with pressure we are dealing with an apparent form of leukonychia (Fig. 8). Initially described in 1956 by their namesake Dr. Robert Muehrcke in patients with severe and long-standing hypoalbuminemia (< 2.2 g/100 mL) [82], currently they are considered indicative of a range of systemic pathologies without hypoalbuminemia, including kidney disease, rheumatoid arthritis, heart transplant [86, 87], and after placement of a left ventricular assist device [88]. Systemic retinoids and various cytostatic regimens have also been observed to cause them. Muehrcke lines are paired, narrow, arcuate pale bands parallel to the lunula that affect all 20 nails and are most prominent on the second, third, and fourth fingernails. They are not permanent and resolve with normalization of the nail bed, for example, with normalization of albumin levels [83].

Fig. 8.

Transversal apparent leukonychia, Muehrcke’s lines

Longitudinal Leukonychia

Longitudinal true leukonychia is caused by alterations of a section of the matrix, resulting in focal parakeratosis and disorganization of keratin filaments, which, if present for a long time, results in a longitudinal white band. It is a typical sign of Darier’s disease where it is associated with longitudinal erythronychia (candy cane nails) (Fig. 9) [101]. The white lines correspond to epithelial hyperplasia of the matrix and the red lines represent thin nails due to matrix disease. Longitudinal true leukonychia without red lines can also be, even if less frequent, a sign of other genodermatoses, including Hailey-Hailey disease [102], and tuberous sclerosis complex [103]. Other nail disorders presenting with linear true leukonychia include onychomatricoma (Fig. 10) [104], onychocytic matricoma [105], and nail matrix lichen planus. A longitudinal band in the great toenail has been associated with chronic trauma in hallux valgus deformity [106].

Fig. 9.

In Darier disease, longitudinal true leukonychia is associated with erythronychia (candy cane nails)

Fig. 10.

Longitudinal true leukonychia in onychomatricoma

Longitudinal apparent leukonychia is also mostly present in one isolated digit. It is often seen in disorders that present with linear erythronychia, in which erythronychia is the result of increased vascularization and leukonychia, the result of decreased vascularization (some nail tumors for example, including longitudinal subungual acanthoma and squamous cell carcinoma) [107]. Apparent leukonychia is also a presenting sign of onychopapilloma, a benign nail bed tumor where leukonychia is due to metaplasia of the nail bed epithelium with a mount of horny cells causing altered light refraction and fibrosis of the nail bed stroma [108–111].

Longitudinal pseudo-leukonychia can be instead caused by onychomycosis. The infection may be recognizable as irregular dense longitudinal white or yellowish bands (spikes) [112].

Partial and Total Leukonychia (Table 3)

Table 3.

Partial and total leukonychia

| True leukonychia | |

| Hereditary | Isolated hereditary leukonychia [114–120] |

| Hereditary syndromes: acrokeratosis verruciformis of Hopf [121], Alagille syndrome [122], Bart–Pumphrey syndrome [123–128], Carvajal/Naxos syndrome [129], congenital fibrosis of the extraocular muscles type 1 [130], FLOTCH syndrome [131–136], hereditary leukonychia totalis, acanthosis-nigricans-like lesions, and hair dysplasia [137], keratoderma-hypotrichosis-leukonychia totalis syndrome [138], keratosis follicularis spinulosa decalvans [139], leukonychia totalis-keratosis pilaris hyperhidrosis [140], linear atrophoderma of Moulin [141], Lowry–Wood syndrome [142], non-mutilating palmoplantar and periorificial keratoderma resembling Olmsted syndrome [143], palmoplantar keratoderma with deafness [144, 145], PLACK syndrome [146–148], POEMS syndrome [149], sebaceous cysts and renal calculi [150] | |

| Neurovascular disorder | Reflex sympathetic dystrophy [21, 151], conduction block in the ulnar nerve in multifocal motor neuropathy [152], peripheral neuropathy |

| Systemic diseases |

Anemia [18], ischemic cardiomyopathy [153], kidney recipients taking immunosuppressives [28, 84], hepatitis C [154], Wilson’s disease [155] Selenium deficiency: in Crohn’s disease [156], in Hirschsprung disease [157] |

| Occupation | Wet work [158], automobile industry workers [159] |

| Trauma | [18] |

| Deficiency | Selenium [157, 156] |

| Drugs | Hydroxyurea [160], trazodone [161] |

| Idiopathic | Congenital or acquired: in boys or men [2, 6, 86, 162–172], congenital or acquired female case [113], with koilonychia [173, 174] |

| Apparent leukonychia | |

| Neurovascular disorders | Lepra [175] |

| Skin disease | Lymphoedema [9], Sézary syndrome [176] |

| Systemic disease | Anemia [177] |

| Physical | Total skin electron beam irradiation therapy [178] |

| Drugs | Vorinostat [179] |

| Terry’s nails | Hepatic cirrhosis (up to 80%) [180–182], acute viral hepatitis [182], autoimmune hepatitis [183], diabetes mellitus [181], erythromelalgia [184], heart failure [181, 185], hematologic disease [186], human immunodeficiency virus [187], hyperthyroid, idiopathic in the elderly [181, 188], Kawasaki disease [189], lepra [175, 190], malnutrition, metastatic carcinoma [181], POEMS syndrome [191], pulmonary tuberculosis, Reiter’s syndrome [192], renal failure [185, 193], tuberculoid leprosy [190], vitiligo [194] |

| Deficiency | Selenium [157, 195] |

| Half-and-half nails |

Renal failure with or without hemodialysis [76], Behçet disease [196], cirrhosis (idiopathic) [197], Crohn’s disease [198], human immunodeficiency virus [187], hyperthyroid disease, isoniazid [199], Kawasaki disease, pellagra [44, 199–201] |

| Pseudoleukonychia | |

| Skin disease | Granulation [202], superficial white onychomycosis [203] |

Congenital partial or total true leukonychia can be idiopathic or inherited. The nails are typically milky/chalky/porcelain white (Fig. 11). In publications reporting on idiopathic congenital true leukonychia, all patients were male, with only one single exception [113]. This sex preference is hard to explain. It could indicate that idiopathic true leukonychia rather is an inherited leukonychia with a recessive X-linked pattern of inheritance. It could also be due to Y-chromosomal inheritance with a variable penetrance.

Fig. 11.

Idiopathic true leukonychia with porcelain white nails

Hereditary leukonychia may exist as an isolated feature, or in association with other cutaneous or systemic pathologies [204]. An autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance is most frequent, but an autosomal recessive pattern has also been reported. A pathogenic mutation in the gene coding for phospholipase C delta-1 (PLCd1) on chromosome 3p22.2, which regulates nail formation downstream of FOXn1 [205], has been identified as relevant in both hereditary autosomal dominant and recessive leukonychia [114, 115, 206] and probably also in leukonychia with sebaceous cysts [150]. Occurring within the context of other pathologies, it has been postulated that congenital familial leukonychia is a symptom of a more complex ectodermal dysplasia involving inconstantly other keratinizing structures and most probably is related to deficiency of a gene regulating the structure of hard keratin [131]. The 12q13 chromosome that encodes the basic and hard keratins is responsible for hereditary leukonychia [116]. In certain cases of the Carvajal/Naxos syndrome, a dominant desmoplakin mutation is associated with leukonychia and oligodontia [129]. The GJB2 gene located on chromosome 13 encodes for connexin 26, which is responsible about half of cases of inherited sensorineural deafness. GJB2 mutations often present with varying cutaneous manifestations, including in Bart–Pumphrey syndrome (MIM: 149200), hystrix-like ichthyosis with deafness (MIM: 602540), keratitis-ichthyosis-deafness syndrome (MIM: 148210), palmoplantar keratoderma with deafness (MIM: 148350), and Vohwinkel syndrome (MIM: 124500), with significant overlap of clinical features [117]. Because leukonychia may be part of some of these syndromes [123, 144, 145], a correct function of connexin 26 appears to be relevant for translucency of the nail plate. It seems reasonable to assume that mutations in genes both responsible for keratins and for proteins important for intercellular connections between epithelial cells are important in several hereditary leukonychia: Connexin 26 is in gap junctions and plays a role in the exchange of ions and small molecules between adjacent cells by forming intercellular channels, and desmoplakin is a critical component of the desmosome, which is also essential in epidermal cell-to-cell contact. Recently, a new autosomal recessive form of the generalized peeling skin syndrome, termed PLACK syndrome (OMIM 616295), has been described. In the acronym, L stands for leukonychia and this is associated with the loss of function mutations in the CAST gene encoding calpastatin [146, 147]. Calpastatin is an endogenous specific inhibitor of calpain, a protease that plays a role in regulating epidermal end differentiation. Congenital leukonychia has a possibility of gradual improvement over the lifetime of an individual [162, 207] and sometimes improves with age, but sometimes not. The improvement seems to be related to maturation of the cells that start producing normal keratins losing the keratohyalin granules.

The acquired form of partial and total true leukonychia is, however, significantly more common and can be associated with several comorbidities, drugs, and exogeneous-acting compounds. Neuropathic disorders, as reflex sympathetic dystrophy, and autonomic abnormalities or vascular diseases can also be responsible. According to Vanhooteghem et al. [151], this leukonychia is secondary to the combination of two phenomena: neurovascular deterioration and chronic slow and progressive trauma to the nail matrix applied by the persistent edema of the fingers and terminal phalanges. Usually, in the latter cases, periungual skin is also involved and the growth rate of the nail plate might be slower.

Apparent partial/total leukonychias can be seen rather frequently and are often medical relevant leukonychias. Half-and-half nails, also known as Lindsay’s nails, are characterized by a sharply demarcated red, pink, or brown discoloration of 20–60% of the distal nail-bed, leading to two-colored nails with a transverse border (Fig. 12). The proximal nail has a whitish ground glass-like appearance, obscuring the lunula, and all nails are involved. It has been defined that if the distal portion is less than 20% of the total nail length, we are instead facing Terry’s nails (Fig. 13) [208].

Fig. 12.

Half-and-half nails (Lindsay’s nails) in a patient with chronic kidney disease

Fig. 13.

Terry’s nails are characterized by subtotal apparent leukonychia with a reddish or brown distal band of less than 20%

Half-and-half nails are detected in approximately in 10–30% of patients with chronic renal disease (uremic patients and patients undergoing hemodialysis) [28, 209, 210]: the discovery should therefore prompt the clinician to evaluate the patient for kidney disease. They also have been reported occasionally in several other circumstances, including Kawasaki’s disease, Behcet’s disease, hepatic cirrhosis, Crohn’s disease, in pellagra, human immunodeficiency virus, after isoniazid therapy but also in healthy persons. In kidney patients, complete disappearance is sometimes noted within 2–3 weeks after successful transplantation [210] while others report even a higher prevalence in renal transplant patients than in patients undergoing hemodialysis [28].

In 1954, Terry described a nail abnormality characterized by a bilaterally symmetrical white nail bed of the fingernails with a distal band, 1–2 mm in length, that had a normal pink or erythematous color [180]. All nails are uniformly involved and often the lunula is not visible. Although the hallmark distal band is typically well defined and contiguous with the end of the nail bed, it may possess an uneven border. It has been supposed that the distal erythematous crescent probably is a prominent onychodermal band. Histological studies of the nail bed have shown vascular changes (telangiectasias) in the bands [181]. The brown tint in the band region observed in some patients could not be explained. Staining did not show abnormal melanin or iron deposition in the band area [181]. The true reasons for the color variations remain unclear. One possibility is that the proximal and distal nail bed have separate blood supplies. Terry found the nail changes in 82% of patients with “alcoholic, postnecrotic, and cholangiolitic” liver cirrhosis but also noticed similar nail changes, currently known as “Terry’s nails” in other underlying medical conditions. While being promoted as one of the most reliable physical signs of cirrhosis [211] and an early sign of autoimmune hepatitis [183], Terry’s nails can also be an indication of chronic renal failure, congestive heart failure, hematologic disease [186], and adult-onset diabetes mellitus [181], but also occur with normal aging. Holzberg and Walker proposed that Terry’s nails are a part of aging and speculated that each of the associated diseases “ages” the nail earlier than normal. The presence of Terry’s nails has also been reported in isolated cases of widely metastatic carcinoma, and in a plethora of infectious and non-infectious diseases.

Sometimes, the circumstances in which total apparent leukonychia appears can easily be explained by changes of the nail bed. For example, by nail bed edema in lymphoedema, paleness of the nail bed in severe anemia, and cicatricial changes after total skin electron beam irradiation therapy. Among the other culprits, selenium deficiency has been reported several times. It has been assumed that selenium deficiency may be responsible for apparent leukonychia in vegetarians in selenium-deficient areas, patients undergoing long-term hemodialysis, long-term parenteral nutrition [157], weight loss, phenylketonuria, malabsorption disorders, and human immunodeficiency virus [195]. Remarkably, selenium deficiency has also been attributed to true leukonychia in Crohn’s disease [156] where selenium supplementation was able to induce complete regression.

Partial/total pseudo-leukonychia can be instead caused by onychomycosis, especially proximal subungual, but also by onycholysis. In these instances, scraping is not possible, and differentiation from true leukonychia can be difficult.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of leukonychia is clinical with the need for an additional test in a minority of cases. The diagnostic algorithm, which is presented in Fig. 14, can be a useful tool in most patients. By combining both the anatomical and the morphological classification, the most likely causes can be identified or excluded. Dermoscopy is very useful to integrate the clinical examination unmasking minor alterations not visible or unclear to the naked eye. This technique has become increasingly popular in recent years to facilitate the clinical diagnosis of nail disorders, opening up a valuable second front with a potential to avoid invasive diagnostic methods. Dermoscopy is also valuable in monitoring the evolution of a disease and response to treatment through stored images. When dealing with leukonychia, besides the morphological aspect that is clearly distinguishable by the naked eye, dermoscopy allows true leukonychia to be better distinguished from apparent leukonychia and pseudoleukonychia [17]. The test of the whitish discoloration of the nail plate that disappears with pressure in cases of apparent leukonychia, but not in true leukonychia, can also be done with the lens of the dermoscope. Moreover, being a color abnormality, leukonychia is better appreciated with an interface solution (ultrasound gel) between the nail plate and the dermoscope lens [212, 213].

Fig. 17.

In Darier disease, dermoscopy shows alternating parallel longitudinal red streaks with thinning of the corresponding nail plate and white bands

In pseudoleukonychia, due to keratin granulation, dermoscopy should be done without interface solution: granulation is constituted by scales, which are better visible using the dry technique. In the presence of punctate leukonychia, dermoscopy is useful to distinguish between the true form and pseudoleukonychia and to better characterize the etiology of the latter: in superficial nail fragility, the areas of leukonychia are more regular and compacted (Fig. 15) and less cotton-candy like as they are in superficial white onychomycosis (Fig. 16). In Darier’s disease, dermoscopy better shows the alternating parallel longitudinal red streaks with thinning of the corresponding nail plate and white bands. The bed vessels are more visible and associated with splinter hemorrhages. Distal splitting of the nail plate may be more or less marked, especially along the red bands (Fig. 17).

Fig. 14.

Algorithm to approach leukonychia. PSO proximal subungual onychomycosis, WSO white superficial onychomycosis

Fig. 15.

Dermoscopy of punctate true pseudoleukonychia of the same patient as in Fig. 3

Fig. 16.

Dermoscopy of punctate true pseudoleukonychia in superficial white onychomycosis

Additional diagnostic procedures may be useful but only in a minority of cases. In pseudoleukonychia, potassium hydroxide or a culture of superficial scrapings may be helpful to confirm an onychomycosis. Blood tests are essential in many patients with widespread true or apparent total, partial, and transversal leukonychia in order to rule out kidney, liver, and other systemic diseases. Nail clippings could be considered in the rare cases of unexplainable Mees’ lines to detect (arsenic) intoxication, but also when onychomatricoma is suspected. Biopsies are rarely indicated, mainly in longitudinal true leukonychia to detect nail lichen planus or Darier disease. When a tumor is the clinical suspect, excision is indicated rather than a biopsy. Neurologic tests including electromyography can be ordered when a underlying neurologic condition is the possible culprit.

Management

Further management of the patients fully depends on the underlying disorder. Treatment of acquired leukonychia is directed at eliminating the underlying cause. In most cases of punctate true leukonychia, this is gentle nail care: avoid manipulating cuticles, and limit the application of frequent irritant or allergenic grooming products (nail polish/remover, artificial nail, nail glue). The frequent application of a moisturizer can be beneficial. Traumas are also a frequent cause of transversal and punctate true leukonychia and should be avoided. In some cases, a gait/shoe analysis might be required. In pseudoleukonychia due to fungi, an antimycotic therapy is often indicated. The management of other localized skin and systemic disorders responsible for leukonychia is outside the scope of this publication. Obviously, referral to another specialist might be essential for patients with an underlying systemic disorder.

Conclusions

A reliable assessment of the patient with leukonychia is essential because a wide array of potential relevant causes may be responsible for the abnormal color, from simple manicure habits to life-threatening liver or kidney failure. In this publication, an easy diagnostic algorithm that combines both morphological and anatomical classifications is proposed in order to help clinicians in dealing with this common color abnormality.

Declarations

Funding

No sources of funding were received for the preparation of this article.

Conflicts of interest/competing interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this article.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and material

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Author contributions

MI had the idea for the article; MI and MP performed the literature search and data analysis; and MI, MS, and MP drafted and critically revised the work.

References

- 1.Weber FP. Some pathologic conditions of the nails. Int Clin. 1899;28(1):108–130. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grossman M, Scher RK. Leukonychia: review and classification. Int J Dermatol. 1990;29(8):535–541. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1990.tb03463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thomson MS. Leuconychia. Proc R Soc Med. 1936;29(5):456–457. doi: 10.1177/003591573602900512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baran R, Perrin C. Transverse leukonychia of toenails due to repeated microtrauma. Br J Dermatol. 1995;133(2):267–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1995.tb02627.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kates SL, Harris GD, Nagle DJ. Leukonychia totalis. J Hand Surg Br. 1986;11(3):465–466. doi: 10.1016/0266-7681(86)90185-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Claudel CD, Zic JA, Boyd AS. Idiopathic leukonychia totalis and partialis in a 12-year-old patient. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44(2 Suppl.):379–380. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2001.111899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marcilly MC, Balme B, Haftek M, Wolf F, Grezard P, Berard F, et al. Sub-total hereditary leukonychia, histopathological and electron microscopy study of "milky" nails. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2003;130(1 Pt 1):50–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Richert B, Caucanas M, Andre J. Diagnosis using nail matrix. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33(2):243–255. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2014.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Le Fourn E, Duhard E, Tauveron V, Maruani A, Samimi M, Lorette G, et al. Changes in the nail unit in patients with secondary lymphoedema identified using clinical, dermoscopic and ultrasound examination. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164(4):765–770. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.10179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leyden JJ, Wood MG. The "half-and-half nail": a uremic onychopathy. Arch Dermatol. 1972;105(4):591–592. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1972.01620070063024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bencini PL, Urbani CE, Crosti C. Onychopathy in the renal transplantation patient. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 1988;123(4):157–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perrin C, Michiels JF, Pisani A, Ortonne JP. Anatomic distribution of melanocytes in normal nail unit: an immunohistochemical investigation. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19(5):462–467. doi: 10.1097/00000372-199710000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perrin C, Michiels JF, Boyer J, Ambrosetti D. Melanocytes pattern in the normal nail, with special reference to nail bed melanocytes. Am J Dermatopathol. 2018;40(3):180–184. doi: 10.1097/dad.0000000000000940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chelidze K, Lipner SR. Nail changes in alopecia areata: an update and review. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57(7):776–783. doi: 10.1111/ijd.13866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roest YBM, van Middendorp HT, Evers AWM, van de Kerkhof PCM, Pasch MC. Nail involvement in alopecia areata: a questionnaire-based survey on clinical signs, impact on quality of life and review of the literature. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;98(2):212–217. doi: 10.2340/00015555-2810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haneke E. Nail psoriasis: clinical features, pathogenesis, differential diagnoses, and management. Psoriasis (Auckl). 2017;7:51–63. doi: 10.2147/PTT.S126281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gallouj S, Mernissi FZ. Transverse leuconychia induced by manicure: is there a contribution from dermoscopy? Pan Afr Med J. 2014;18:39. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2014.18.39.3761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bae SH, Lee MY, Lee JB. Distinct patterns and aetiology of chromonychia. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;98(1):108–113. doi: 10.2340/00015555-2798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ficicioglu S, Korkmaz S. Onychophagia induced melanonychia, splinter hemorrhages, leukonychia, and pterygium inversum unguis concurrently. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2018;2018:3230582. doi: 10.1155/2018/3230582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bowling JC, McIntosh S, Agnew KL. Transverse leukonychia of the fingernail following proximal nail fold trauma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2004;29(1):96. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2004.01432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duman I, Aydemir K, Taskaynatan MA, Dincer K. Unusual cases of acquired leukonychia totalis and partialis secondary to reflex sympathetic dystrophy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21(10):1445–1446. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2007.02262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Swart E, Lochner JD. Skin conditions in epileptics. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1992;17(3):169–172. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1992.tb00197.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dotz WI, Lieber CD, Vogt PJ. Leukonychia punctata and pitted nails in alopecia areata. Arch Dermatol. 1985;121(11):1452–1454. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1985.01660110100025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Elmas OF. Uncovering subtle nail involvement in lichen planus with dermoscopy: a prospective, controlled study. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2020;37(3):396–400. doi: 10.5114/ada.2020.96298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ehsani AH, Nasimi M, Azizpour A, Noormohammadpoor P, Kamyab K, Seirafi H, et al. Nail changes in early mycosis fungoides. Skin Appendage Disord. 2018;4(1):55–59. doi: 10.1159/000478946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Topal IO, Gungor S, Kocaturk OE, Duman H, Durmuscan M. Nail abnormalities in patients with vitiligo. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91(4):442–445. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20164620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pfeiffer CC, Jenney EH. Letter: fingernail white spots: possible zinc deficiency. JAMA. 1974;228(2):157. doi: 10.1001/jama.1974.03230270017005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saray Y, Seckin D, Gulec AT, Akgun S, Haberal M. Nail disorders in hemodialysis patients and renal transplant recipients: a case-control study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50(2):197–202. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2003.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ena P, Mazzarello V, Fenu G, Rubino C. Leukonychia from 2-ethyl-cyanoacrylate glue. Contact Dermatitis. 2000;42(2):105–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gupta AK, Baran R, Summerbell RC. Fusarium infections of the skin. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2000;13(2):121–128. doi: 10.1097/00001432-200004000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Gelderen de Komaid A, Borges de Kestelman I, Duran EL. Etiology and clinical characteristics of mycotic leukonychia. Mycopathologia. 1996;136(1):9–15. doi: 10.1007/BF00436654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moreno-Coutino G, Toussaint-Caire S, Arenas R. Clinical, mycological and histological aspects of white onychomycosis. Mycoses. 2010;53(2):144–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2008.01683.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rathore T, Millington GW. Mycotic pseudoleuconychia affecting the fingernails. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;35(5):558–559. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2010.03792.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chessa MA, Iorizzo M, Richert B, López-Estebaranz JL, Rigopoulos D, Tosti A, et al. Pathogenesis, clinical signs and treatment recommendations in brittle nails: a review. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2020;10(1):15–27. doi: 10.1007/s13555-019-00338-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mees RA. Een verschijnsel bij polyneuritis arsenicosa. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 1919;63:391–396. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Conomy JP. A succession of Mees' lines in arsenical polyneuropathy. Postgrad Med. 1972;52(6):97–99. doi: 10.1080/00325481.1972.11713321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jenkins RB. Inorganic arsenic and the nervous system. Brain. 1966;89(3):479–498. doi: 10.1093/brain/89.3.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maino KL, Stashower ME. Traumatic transverse leukonychia. Skinmed. 2004;3(1):53–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-9740.2004.02369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Honda M, Hattori S, Koyama L, Iwasaki T, Takagi O. Leukonychia striae. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112(8):1147. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1976.01630320053016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Howard SR, Siegfried EC. A case of leukonychia. J Pediatr. 2013;163(3):914–915. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Anoun S, Qachouh M, Lamchahab M, Quessar A, Benchekroun S. Mees' lines in an acute myeloid leukemia patient. Turk J Haematol. 2013;30(3):340. doi: 10.4274/Tjh.2013.0048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Harris AJ, Burge SM, Gardener BP. Unilateral nail dystrophy after C4 complete spinal cord injury. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135(5):855–857. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1996.tb03904.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bryer-Ash M, Kennedy C, Ridgway H. A case of leuconychia striata with severe erythema multiforme. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1981;6(5):565–567. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1981.tb02355.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Donald GF, Hunter GA, Gillam BD. Transverse leukonychia due to pellagra. Arch Dermatol. 1962;85:530–531. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1962.01590040094015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Podjasek JO, Cook-Norris RH. Mees' lines. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2010;48(9):958. doi: 10.3109/15563650.2010.511230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sharma S, Gupta A, Deshmukh A, Puri V. Arsenic poisoning and Mees' lines. QJM. 2016;109(8):565–566. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcw068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Seavolt MB, Sarro RA, Levin K, Camisa C. Mees' lines in a patient following acute arsenic intoxication. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41(7):399–401. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2002.01535_2.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Quecedo E, Sanmartin O, Febrer MI, Martinez-Escribano JA, Oliver V, Aliaga A. Mees' lines: a clue for the diagnosis of arsenic poisoning. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132(3):349–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Welter A, Michaux M, Blondeel A. Mees' lines in a case of acute arsenic poisoning. Dermatologica. 1982;165(5):482–483. doi: 10.1159/000249991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Perosio AM. Toxic arsenical polyneuritis & Mees' lines of the fingers. Prensa Med Argent. 1957;44(19):1454–1457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Assadi F. Leukonychia associated with increased blood strontium level. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2005;44(6):531–533. doi: 10.1177/000992280504400610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhao G, Ding M, Zhang B, Lv W, Yin H, Zhang L, et al. Clinical manifestations and management of acute thallium poisoning. Eur Neurol. 2008;60(6):292–297. doi: 10.1159/000157883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lu CI, Huang CC, Chang YC, Tsai YT, Kuo HC, Chuang YH, et al. Short-term thallium intoxication: dermatological findings correlated with thallium concentration. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143(1):93–98. doi: 10.1001/archderm.143.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Samman PD, Johnston EN. Nail damage associated with handling of paraquat and diquat. Br Med J. 1969;1(5647):818–819. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5647.818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dobbelaere F, Bouffioux J. Leukonychia in bands due to paraquat. Arch Belg Dermatol. 1974;30(4):283–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kibby T, Ring DS. Nail injury and diquat exposure: forgotten but not gone. Dermatitis. 2012;23(4):176–178. doi: 10.1097/DER.0b013e318262ca83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Baran RL. Letter: nail damage caused by weed killers and insecticides. Arch Dermatol. 1974;110(3):467. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1974.01630090093038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Siragusa M, Alberti A, Schepis C. Mees' lines due to cyclosporin. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140(6):1198–1199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kinjo T, Shibahara D, Higa F, Fujita J. Beau's lines and Mees' lines formations after chemotherapy. Intern Med. 2015;54(17):2281. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.54.5166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ceyhan AM, Yildirim M, Bircan HA, Karayigit DZ. Transverse leukonychia (Mees' lines) associated with docetaxel. J Dermatol. 2010;37(2):188–189. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2009.00744.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Helander A, Bradley M, Hasselblad A, Norlen L, Vassilaki I, Backberg M, et al. Acute skin and hair symptoms followed by severe, delayed eye complications in subjects using the synthetic opioid MT-45. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176(4):1021–1027. doi: 10.1111/bjd.15174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zweegers J, Bovenschen HJ. Acitretin-induced transverse leukonychia. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53(3):e221–e222. doi: 10.1111/ijd.12012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Baran R, Brun P, Juhlin L. Transverse leukonychia induced by etretinate. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1983;110(8):657. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gregoriou S, Banaka F, Rigopoulos D. Isotretinoin-induced transverse leuconychia. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30(2):385–386. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Piraccini BM, Tosti A. Drug-induced nail disorders: incidence, management and prognosis. Drug Saf. 1999;21(3):187–201. doi: 10.2165/00002018-199921030-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chaudhry SI, Black MM. True transverse leuconychia with spontaneous resolution during pregnancy. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154(6):1212–1213. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fujita Y, Sato-Matsumura KC, Doi I, Takaoka K. Transverse leukonychia (Mees' lines) associated with pleural empyema. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2007;32(1):127–128. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2006.02178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mautner GH, Lu I, Ort RJ, Grossman ME. Transverse leukonychia with systemic infection. Cutis. 2000;65(5):318–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fernandez-Nieto D, Jimenez-Cauhe J, Ortega-Quijano D, Diaz-Guimaraens B, Dominguez-Santas M, Martinez-Rubio J. Transverse leukonychia (Mees' lines) nail alterations in a COVID-19 patient. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33(6):e13863. doi: 10.1111/dth.13863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ide S, Morioka S, Inada M, Ohmagari N. Beau's lines and leukonychia in a COVID-19 patient. Intern Med. 2020;59(24):3259. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.6112-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Berard R, Scuccimarri R, Chedeville G. Leukonychia striata in Kawasaki disease. J Pediatr. 2008;152(6):889. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zizmor J, Deluty S. Acquired leukonychia striata. Int J Dermatol. 1980;19(1):49–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1980.tb01996.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hepburn MJ, English JC, 3rd, Meffert JJ. Mees' lines in a patient with multiple parasitic infections. Cutis. 1997;59(6):321–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jarek MJ, Finger DR, Gillil WR, Giandoni MB. Periorbital edema and Mees' lines in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Clin Rheumatol. 1996;2(3):156–159. doi: 10.1097/00124743-199606000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mahe E, Morelon E, Lechaton S, Kreis H, De Prost Y, Bodemer C. Sirolimus-induced onychopathy in renal transplant recipients. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2006;133(6–7):531–535. doi: 10.1016/s0151-9638(06)70957-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Udayakumar P, Balasubramanian S, Ramalingam KS, Lakshmi C, Srinivas CR, Mathew AC. Cutaneous manifestations in patients with chronic renal failure on hemodialysis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2006;72(2):119–125. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.25636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Held JL, Chew S, Grossman ME, Kohn SR. Transverse striate leukonychia associated with acute rejection of renal allograft. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20(3):513–514. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(89)80096-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lee SH, Kim WH. Mees' lines associated with heart failure. QJM. 2019;112(3):223. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcy214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hutchison SJ, Amin S. Everest nails. N Engl J Med. 1997;336(3):229. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199701163360317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Aujayeb A. Mees' lines in high altitude mountaineering. BMJ Case Rep. 2019;12(3):e229644. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2019-229644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Botella de Maglia J. Altitude leukonychia. Rev Clin Esp. 1998;198(4):262–263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Muehrcke RC. The finger-nails in chronic hypoalbuminaemia; a new physical sign. Br Med J. 1956;1(4979):1327–1328. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.4979.1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Williams V, Jayashree M. Muehrcke Lines in an Infant. J Pediatr. 2017;189:234. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Abdelaziz AM, Mahmoud KM, Elsawy EM, Bakr MA. Nail changes in kidney transplant recipients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25(1):274–277. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chavez-Lopez MA, Arce-Martinez FJ, Tello-Esparza A. Muehrcke lines associated to active rheumatoid arthritis. J Clin Rheumatol. 2013;19(1):30–31. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0b013e31827d8a45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Canavan T, Tosti A, Mallory H, McKay K, Cantrell W, Elewski B. An idiopathic leukonychia totalis and leukonychia partialis: case report and review of the literature. Skin Appendage Disord. 2015;1(1):38–42. doi: 10.1159/000380956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Nabai H. Nail changes before and after heart transplantation: personal observation by a physician. Cutis. 1998;61(1):31–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Weiser JA, Rogers HD, Scher RK, Grossman ME. Signs of a "broken heart": suspected Muehrcke lines after cardiac surgery. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143(6):815–816. doi: 10.1001/archderm.143.6.815-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Mohaghegh F, Danesh F. Muehrcke's lines in a psoriatic patient: a possible association with acitretin therapy. Clin Case Rep. 2019;7(11):2212–2214. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.2434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Dasanu CA, Ichim TE, Alexandrescu DT. Muehrcke's lines (Leukonychia striata) due to transretinoic acid therapy for acute promyelocytic leukemia. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2013;19(4):377–379. doi: 10.1177/1078155212468923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Unamuno P, Fernandez-Lopez E, Santos C. Leukonychia due to cytostatic agents. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1992;17(4):273–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1992.tb02166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Chen GY, Chen W, Huang WT. Single transverse apparent leukonychia caused by 5-fluorouracil plus leucovorin. Dermatology. 2003;207(1):86–87. doi: 10.1159/000070954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Saraswat N, Sood A, Verma R, Kumar D, Kumar S. Nail changes induced by chemotherapeutic agents. Indian J Dermatol. 2020;65(3):193–198. doi: 10.4103/ijd.IJD_37_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Bianchi L, Iraci S, Tomassoli M, Carrozzo AM, Nini G. Coexistence of apparent transverse leukonychia (Muehrcke's lines type) and longitudinal melanonychia after 5-fluorouracil/adriamycin/cyclophosphamide chemotherapy. Dermatology. 1992;185(3):216–217. doi: 10.1159/000247451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Baran R. Proximal subungual Candida onychomycosis: an unusual manifestation of chronic mucocutaneous candidosis. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137(2):286–288. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1997.18221900.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Chen W, Yu YS, Liu YH, Sheen JM, Hsiao CC. Nail changes associated with chemotherapy in children. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21(2):186–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2006.01887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Chapman S, Cohen PR. Transverse leukonychia in patients receiving cancer chemotherapy. South Med J. 1997;90(4):395–398. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199704000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Robert C, Sibaud V, Mateus C, Verschoore M, Charles C, Lanoy E, et al. Nail toxicities induced by systemic anticancer treatments. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(4):e181–e189. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)71133-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Friedman SJ. Leukonychia striata associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;15(3):536–538. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(86)80503-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Burtscher M, Likar R. Leukonychia following high altitude exposure. High Alt Med Biol. 2002;3(1):93–94. doi: 10.1089/152702902753639612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Halteh P, Jorizzo JL, Lipner SR. Darier disease: candy-cane nails and hyperkeratotic papules. Postgrad Med J. 2016;92(1089):425–426. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2016-134002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kirtschig G, Effendy I, Happle R. Leukonychia longitudinalis as the primary symptom of Hailey-Hailey disease. Hautarzt. 1992;43(7):451–452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Aldrich CS, Hong CH, Groves L, Olsen C, Moss J, Darling TN. Acral lesions in tuberous sclerosis complex: insights into pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63(2):244–251. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.08.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Lesort C, Debarbieux S, Duru G, Dalle S, Poulhalon N, Thomas L. Dermoscopic features of onychomatricoma: a study of 34 cases. Dermatology. 2015;231(2):177–183. doi: 10.1159/000431315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Spaccarelli N, Wanat KA, Miller CJ, Rubin AI. Hypopigmented onychocytic matricoma as a clinical mimic of onychomatricoma: clinical, intraoperative and histopathologic correlations. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40(6):591–594. doi: 10.1111/cup.12122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Wollina U, Bula P. Longitudinal 'half-and-half nails' or true leukonychia. Skin Appendage Disord. 2016;1(4):185–186. doi: 10.1159/000444757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.de Berker DA, Perrin C, Baran R. Localized longitudinal erythronychia: diagnostic significance and physical explanation. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140(10):1253–1257. doi: 10.1001/archderm.140.10.1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Tosti A, Schneider SL, Ramirez-Quizon MN, Zaiac M, Miteva M. Clinical, dermoscopic, and pathologic features of onychopapilloma: a review of 47 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(3):521–526. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.08.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Halteh P, Magro C, Scher RK, Lipner SR. Onychopapilloma presenting as leukonychia: case report and review of the literature. Skin Appendage Disord. 2017;2(3–4):89–91. doi: 10.1159/000448105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Criscione V, Telang G, Jellinek NJ. Onychopapilloma presenting as longitudinal leukonychia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63(3):541–542. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Higashi N, Sugai T, Yamamoto T. Leukonychia striata longitudinalis. Arch Dermatol. 1971;104(2):192–196. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1971.04000200080014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Lipner SR, Scher RK. Evaluation of nail lines: color and shape hold clues. Cleve Clin J Med. 2016;83(5):385–391. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.83a.14187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Davis-Fontenot K, Hagan C, Emerson A, Gerdes M. Congenital isolated leukonychia. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23(7):13030/qt85b4w7z3. doi: 10.5070/D3237035757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Kiuru M, Kurban M, Itoh M, Petukhova L, Shimomura Y, Wajid M, et al. Hereditary leukonychia, or porcelain nails, resulting from mutations in PLCD1. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;88(6):839–844. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Nomikos M, Thanassoulas A, Beck K, Theodoridou M, Kew J, Kashir J, et al. Mutations in PLCdelta1 associated with hereditary leukonychia display divergent PIP2 hydrolytic function. FEBS J. 2016;283(24):4502–4514. doi: 10.1111/febs.13939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Norgett EE, Wolf F, Balme B, Leigh IM, Perrot H, Kelsell DP, et al. Hereditary 'white nails': a genetic and structural study. Br J Dermatol. 2004;151(1):65–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.05994.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.DeMille D, Carlston CM, Tam OH, Palumbos JC, Stalker HJ, Mao R, et al. Three novel GJB2 (connexin 26) variants associated with autosomal dominant syndromic and nonsyndromic hearing loss. Am J Med Genet A. 2018;176(4):945–950. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.38648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Mir H, Khan S, Arif MS, Ali G, Wali A, Ansar M, et al. Mutations in the gene phospholipase C, delta-1 (PLCD1) underlying hereditary leukonychia. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22(6):736–739. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2012.1852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Khan AK, Khan SA, Muhammad N, Muhammad N, Ahmad J, Nawaz H, et al. Mutation in phospholipase C, delta1 (PLCD1) gene underlies hereditary leukonychia in a Pashtun family and review of the literature. Balkan J Med Genet. 2018;21(1):69–72. doi: 10.2478/bjmg-2018-0001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Xue K, Zheng Y, Shen C, Cui Y. Identification of a novel PLCD1 mutation in Chinese Han pedigree with hereditary leukonychia and koilonychia. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2019;18(3):912–915. doi: 10.1111/jocd.12707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Williams GM, Lincoln M. Acrokeratosis verruciformis of Hopf. Treasure Island: StatPearls; 2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Cambiaghi S, Riva S, Ramaccioni V, Gridelli B, Gelmetti C. Steatocystoma multiplex and leuconychia in a child with Alagille syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 1998;138(1):150–154. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.02043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Bart RS, Pumphrey RE. Knuckle pads, leukonychia and deafness: a dominantly inherited syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1967;276(4):202–207. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196701262760403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Kose O, Baloglu H. Knuckle pads, leukonychia and deafness. Int J Dermatol. 1996;35(10):728–729. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1996.tb00649.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Balighi K, Moeineddin F, Lajevardi V, Ahmadreza R. A family with leukonychia totalis. Indian J Dermatol. 2010;55(1):102–104. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.60365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Gonul M, Gul U, Hizli P, Hizli O. A family of Bart-Pumphrey syndrome. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2012;78(2):178–181. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.93636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Ramer JC, Vasily DB, Ladda RL. Familial leuconychia, knuckle pads, hearing loss, and palmoplantar hyperkeratosis: an additional family with Bart-Pumphrey syndrome. J Med Genet. 1994;31(1):68–71. doi: 10.1136/jmg.31.1.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Richard G, Brown N, Ishida-Yamamoto A, Krol A. Expanding the phenotypic spectrum of Cx26 disorders: Bart-Pumphrey syndrome is caused by a novel missense mutation in GJB2. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;123(5):856–863. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.23470.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Boule S, Fressart V, Laux D, Mallet A, Simon F, de Groote P, et al. Expanding the phenotype associated with a desmoplakin dominant mutation: Carvajal/Naxos syndrome associated with leukonychia and oligodontia. Int J Cardiol. 2012;161(1):50–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.06.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Karadeniz N, Erkek E, Taner P. Unexpected clinical involvement of hereditary total leuconychia with congenital fibrosis of the extraocular muscles in three generations. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34(8):e570–e572. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2009.03246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Grosshans EM. Familial leukonychia totalis. Acta Derm Venereol. 1998;78(6):481. doi: 10.1080/000155598442836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Slee JJ, Wallman IS, Goldblatt J. A syndrome of leukonychia totalis and multiple sebaceous cysts. Clin Dysmorphol. 1997;6(3):229–231. doi: 10.1097/00019605-199707000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Bushkell LL, Gorlin RJ. Leukonychia totalis, multiple sebaceous cysts, and renal calculi: a syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1975;111(7):899–901. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1975.01630190089011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Rodriguez-Lojo R, Del Pozo J, Sacristan F, Barja J, Pineyro-Molina F, Perez-Varela L. Leukonychia totalis associated with multiple pilar cysts: report of a five-generation family: FLOTCH syndrome? Eur J Dermatol. 2011;21(4):484–486. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2011.1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Mutoh M, Niiyama S, Nishikawa S, Oharaseki T, Mukai H. A syndrome of leukonychia, koilonychia and multiple pilar cysts. Acta Derm Venereol. 2015;95(2):249–250. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Friedel J, Heid E, Grosshans E. The FLOTCH syndrome. Familial occurrence of total LeukOnychia, Trichilemmal cysts and Ciliary dystrophy with dominant autosomal Heredity. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1986;113(6–7):549–553. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Le Corre Y, Steff M, Croue A, Filmon R, Verret JL, Le Clech C. Hereditary leukonychia totalis, acanthosis-nigricans-like lesions and hair dysplasia: a new syndrome? Eur J Med Genet. 2009;52(4):229–233. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Wang H, Cao X, Lin Z, Lee M, Jia X, Ren Y, et al. Exome sequencing reveals mutation in GJA1 as a cause of keratoderma-hypotrichosis-leukonychia totalis syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 2015;24(22):6564. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddv365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Azakli HN, Agirgol S, Takmaz S, Dervis E. Keratosis follicularis spinulosa decalvans associated with leukonychia. West Indian Med J. 2014;63(5):552–553. doi: 10.7727/wimj.2013.096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Galadari I, Mohsen S. Leukonychia totalis associated with keratosis pilaris and hyperhidrosis. Int J Dermatol. 1993;32(7):524–525. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1993.tb02841.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Atasoy M, Aliagaoglu C, Sahin O, Ikbal M, Gursan N. Linear atrophoderma of Moulin together with leuconychia: a case report. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20(3):337–340. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2006.01434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Yamamoto T, Tohyama J, Koeda T, Maegaki Y, Takahashi Y. Multiple epiphyseal dysplasia with small head, congenital nystagmus, hypoplasia of corpus callosum, and leukonychia totalis: a variant of Lowry-Wood syndrome? Am J Med Genet. 1995;56(1):6–9. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320560103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Nofal A, Assaf M, Nassar A, Nofal E, Shehab M, El-Kabany M. Nonmutilating palmoplantar and periorificial kertoderma: a variant of Olmsted syndrome or a distinct entity? Int J Dermatol. 2010;49(6):658–665. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2009.04429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Crosti C, Sala F, Bertani E, Gasparini G, Menni S. Leukonychia totalis and ectodermal dysplasia: report of 2 cases. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1983;110(8):617–622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Schwann J. Keratosis palmaris et plantaris with congenital deafness and total leukonychia. Dermatologica. 1963;126:335–353. doi: 10.1159/000254936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Alkhalifah A, Chiaverini C, Del Giudice P, Supsrisunjai C, Hsu CK, Liu L, et al. PLACK syndrome resulting from a new homozygous insertion mutation in CAST. J Dermatol Sci. 2017;88(2):256–258. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2017.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Lin Z, Zhao J, Nitoiu D, Scott CA, Plagnol V, Smith FJ, et al. Loss-of-function mutations in CAST cause peeling skin, leukonychia, acral punctate keratoses, cheilitis, and knuckle pads. Am J Hum Genet. 2015;96(3):440–447. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.12.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Boggs JME, Irvine AD. PLACK syndrome resulting from a novel homozygous variant in CAST. Pediatr Dermatol. 2021;38(1):210–212. doi: 10.1111/pde.14383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Crow RS. Peripheral neuritis in myelomatosis. Br Med J. 1956;2(4996):802–804. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.4996.802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Shimomura Y, O'Shaughnessy R, Rajan N. PLCD1 and pilar cysts. J Invest Dermatol. 2019;139(10):2075–2077. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2019.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Vanhooteghem O, Andre J, Halkin V, Song M. Leuconychia in reflex sympathetic dystrophy: a chance association? Br J Dermatol. 1998;139(2):355–356. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.02390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Turner MR. Unilateral leukonychia and hair depigmentation in multifocal motor neuropathy. Neurology. 2013;81(20):1800–1801. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000435562.07857.fd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Antonarakis ES. Images in clinical medicine: acquired leukonychia totalis. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(2):e2. doi: 10.1056/NEJMicm050758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Salem A, Gamil H, Hamed M, Galal S. Nail changes in patients with liver disease. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24(6):649–654. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03476.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Verma R, Junewar V, Sahu R. Pathological fractures as an initial presentation of Wilson's disease. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013:bcr2013008857. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-008857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Hasunuma N, Umebayashi Y, Manabe M. True leukonychia in Crohn disease induced by selenium deficiency. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150(7):779–780. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.6701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Yun JW, Woo YR, Kim M, Chung JH, Jung MH, Park HJ. Image Gallery: leukonychia induced by selenium deficiency related to long-term parenteral nutrition in a patient with Hirschsprung disease. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177(3):e72. doi: 10.1111/bjd.15772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Samuel HC. Case of leuconychia. Proc R Soc Med. 1919;12(Dermatol Sect):57–58. doi: 10.1177/003591571901200335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Yakut Y, Ucmak D, Akkurt ZM, Akdeniz S, Palanci Y, Sula B. Occupational skin diseases in automotive industry workers. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2014;33(1):11–15. doi: 10.3109/15569527.2013.787088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Zargari O, Kimyai-Asadi A, Jafroodi M. Cutaneous adverse reactions to hydroxyurea in patients with intermediate thalassemia. Pediatr Dermatol. 2004;21(6):633–635. doi: 10.1111/j.0736-8046.2004.21603.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Longstreth GF, Hershman J. Trazodone-induced hepatotoxicity and leukonychia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;13(1):149–150. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(85)80328-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Butterworth T. Leukonychia partialis: a phase of leukonychia totalis. Cutis. 1982;29(4):363–364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Stewart L, Young E, Lim HW. Idiopathic leukonychia totalis and partialis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;13(1):157–158. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(85)80337-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Ganesh A, Priyanka G. Idiopathic congenital true leukonychia totalis. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2014;5(Suppl. 1):S65–S66. doi: 10.4103/2229-5178.144551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Bakry OA, Attia AM, Shehata WA. Idiopathic acquired true leukonychia totalis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31(3):404–405. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2012.01826.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Arsiwala SZ. Idiopathic acquired persistent true partial to total leukonychia. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2012;78(1):107–108. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.90962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Bongiorno MR, Arico M. Idiopathic acquired leukonychia in a 34-year-old patient. Case Rep Med. 2009;2009:495809. doi: 10.1155/2009/495809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Park HJ, Lee CN, Kim JE, Jeong E, Lee JY, Cho BK. A case of idiopathic leuconychia totalis and partialis. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152(2):401–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06406.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Kim SW, Kim MS, Han TY, Lee JH, Son SJ. Idiopathic acquired true leukonychia totalis and partialis. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26(2):262–263. doi: 10.5021/ad.2014.26.2.262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170.Das A, Bandyopadhyay D, Podder I. Idiopathic acquired true leukonychia totalis. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61(1):127. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.174193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171.Pielasinski-Rodriguez U, Machan S, Farina-Sabaris MC, Requena-Caballero L. Acquired total leukonychia in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2012;103(10):934–935. doi: 10.1016/j.adengl.2012.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172.Brown PJ, Padgett JK, English JC., 3rd Sporadic congenital leukonychia with partial phenotype expression. Cutis. 2000;66(2):117–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 173.Kwon NH, Kim JE, Cho BK, Jeong EG, Park HJ. Sporadic congenital leukonychia with koilonychia. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51(11):1400–1402. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2010.04750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 174.Clayton N, Atkar R, Verdolini R. Ten bright-white fingernails in two young healthy patients. Congenital total (patient 1) and subtotal (patient 2) leuconychia (white nails syndrome, or milky nails) Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37(2):201–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2011.04084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 175.Belinchon Romero I, Ramos Rincon JM, Reyes RF. Nail involvement in leprosy. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2012;103(4):276–284. doi: 10.1016/j.ad.2011.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 176.Damasco FM, Geskin LJ, Akilov OE. Nail changes in Sezary syndrome: a single-center study and review of the literature. J Cutan Med Surg. 2019;23(4):380–387. doi: 10.1177/1203475419839937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 177.McLachlan I, Visser WI, Jordaan HF. Skin conditions in a South African tuberculosis hospital: prevalence, description, and possible associations. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55(11):1234–1241. doi: 10.1111/ijd.13355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 178.Eros N, Marschalko M, Bajcsay A, Polgar C, Fodor J, Karpati S. Transient leukonychia after total skin electron beam irradiation. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25(1):115–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03692.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 179.Anderson KA, Bartell HL, Olsen EA. Leukonychia related to vorinostat. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145(11):1338–1339. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2009.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 180.Terry R. White nails in hepatic cirrhosis. Lancet. 1954;266(6815):757–759. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(54)92717-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 181.Holzberg M, Walker HK. Terry's nails: revised definition and new correlations. Lancet. 1984;1(8382):896–899. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)91351-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 182.Albuquerque A, Sarmento J, Macedo G. Hepatobiliary and pancreatic: Terry's nails and liver disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27(9):1539. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2012.07184.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 183.Navarro-Trivino FJ, Linares-Gonzalez L, Rodenas-Herranz T. Terry's nails as the first clinical sign of autoimmune hepatitis. Rev Clin Esp. 2019;S0014–2565(19):30156. doi: 10.1016/j.rce.2019.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 184.Yuan Z, He C. Primary erythromelalgia with leukonychia combined with ulcerations and infection by Monilia guilliermondii. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2011;27(3):114–117. doi: 10.1016/j.kjms.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 185.Nia AM, Ederer S, Dahlem KM, Gassanov N, Er F. Terry's nails: a window to systemic diseases. Am J Med. 2011;124(7):602–604. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2010.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 186.Jemec GB, Kollerup G, Jensen LB, Mogensen S. Nail abnormalities in nondermatologic patients: prevalence and possible role as diagnostic aids. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32(6):977–981. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(95)91335-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 187.Cribier B, Mena ML, Rey D, Partisani M, Fabien V, Lang JM, et al. Nail changes in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus: a prospective controlled study. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134(10):1216–1220. doi: 10.1001/archderm.134.10.1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 188.Saraya T, Ariga M, Kurai D, Takeshita N, Honda K, Goto H. Terry's nails as a part of aging. Intern Med. 2008;47(6):567–568. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.47.0788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 189.Iosub S, Gromisch DS. Leukonychia partialis in Kawasaki disease. J Infect Dis. 1984;150(4):617–618. doi: 10.1093/infdis/150.4.617-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 190.Singh PK, Nigam PK, Singh G. Terry's nails in a case of leprosy. Indian J Lepr. 1986;58(1):107–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 191.Miest RY, Comfere NI, Dispenzieri A, Lohse CM, El-Azhary RA. Cutaneous manifestations in patients with POEMS syndrome. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52(11):1349–1356. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2012.05648.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 192.Coskun BK, Saral Y, Ozturk P, Coskun N. Reiter syndrome accompanied by Terry nail. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19(1):87–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2004.01045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 193.Blyumin M, Khachemoune A, Bourelly P. What is your diagnosis? Terry nails. Cutis. 2005;76(3):172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 194.Anbar T, Hay RA, Abdel-Rahman AT, Moftah NH, Al-Khayyat MA. Clinical study of nail changes in vitiligo. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2013;12(1):67–72. doi: 10.1111/jocd.12022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 195.DiBaise M, Tarleton SM. Hair, Nails, and Skin: differentiating cutaneous manifestations of micronutrient deficiency. Nutr Clin Pract. 2019;34(4):490–503. doi: 10.1002/ncp.10321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 196.Sahin AA, Kalyoncu AF, Selcuk ZT, Coplu L, Celebi C, Baris YI. Behcet's disease with half and half nail and pulmonary artery aneurysm. Chest. 1990;97(5):1277. doi: 10.1378/chest.97.5.1277a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 197.Verma P, Mahajan G. Idiopathic 'Half and half' nails. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29(7):1452. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]