Abstract

Opportunistic onychomycosis caused by nondermatophytic molds may differ in treatment from tinea unguium. Confirmed diagnosis of opportunistic onychomycosis classically requires more than one laboratory analysis to show consistency of fungal outgrowth. Walshe and English in 1966 proposed to extract sufficient diagnostic information from a single patient consultation by counting the number of nail fragments positive for inoculum of the suspected fungus. Twenty fragments were plated per patient, and each case in which five or more fragments grew the same mold was considered an infection by that mold, provided that compatible filaments were also seen invading the nail tissue by direct microscopy. This widely used and often recommended method has never been validated. Therefore, the validity of substituting any technique based on inoculum counting for conventional follow-up study in the diagnosis of opportunistic onychomycosis was investigated. Sampling of 473 patients was performed repeatedly. Nail specimens were examined by direct microscopy, and 15 pieces were plated on standard growth media. After 3 weeks, outgrowing dermatophytes were recorded, and pieces growing any nondermatophyte mold were counted. Patients returned on two to eight additional occasions over a 1- to 3-year period for similar examinations. Onychomycosis was etiologically classified based on long-term study. Opportunistic onychomycosis was definitively established for 86 patients. Counts of nondermatophyte molds in initial examinations were analyzed to determine if they successfully predicted both true cases of opportunistic onychomycosis and cases of insignificant mold contamination. There was a strong positive statistical association between mold colony counts and true opportunistic onychomycosis. Logistic regression analysis, however, determined that even the highest counts predicted true cases of opportunistic onychomycosis only 89.7% of the time. The counting criterion suggested by Walshe and English was correct only 23.2% of the time. Acremonium infections were especially likely to be correctly predicted by inoculum counting. Inoculum counting could be used to indicate a need for repeat studies in cases of false-negative results from laboratory direct microscopy. Inoculum counting cannot serve as a valid substitute for follow-up study in the diagnosis of opportunistic onychomycosis. It may, nonetheless, provide useful information both to the physician and to the laboratory, and it may be especially valuable when the patient does not present for follow-up sampling.

One of the most controversial questions in the diagnosis of onychomycosis is how to identify, practically and realistically, an opportunistic nail infection genuinely caused by a normally saprobic filamentous fungus. Common fungi with known primary habitats in soil, decaying plant debris, or plant disease, such as various Scopulariopsis, Fusarium, and Aspergillus species, have been rigorously demonstrated to cause occasional cases of onychomycosis (35–37). In total, such cases may be conservatively estimated as accounting for approximately 3 to 4% of total onychomycosis (17, 38). Normally saprobic fungi, unlike dermatophytes (and unlike dermatomycotic Scytalidium species isolated at temperate latitudes) (35–37), cannot be assumed to be pathogenic each time they are isolated. Many, in fact, are more common as insignificant nail contaminants than as etiologic agents.

For at least 4 decades, the accepted “gold standard” for rigorous demonstration of infections by such organisms has consisted of (i) the demonstration of invasive fungal elements by direct microscopy (e.g., potassium or sodium hydroxide [KOH or NaOH] test) compatible with the fungus isolated (ii) and successively repeated isolation on two or more separate occasions of the suspected causal agent from the patient, in the absence of any outgrowth of a dermatophyte or dermatomycotic Scytalidium sp. (10, 35–37). The latter criterion is based on the logic of Koch's first postulate of pathogenicity: a purported etiologic agent should be constantly associated with the disease it is alleged to cause (35–37). Contamination events, however, are unlikely to be repeated identically.

Extending the same logic, mixed infections may be classically recognized by demonstrating dermatophyte outgrowth on at least one occasion and consistent outgrowth of a mold on at least three occasions.

Despite the fundamental soundness of this gold standard, it is difficult to employ in practice. Patients attend the dermatology clinic seeking relief, not intending to involve themselves in protracted causality studies. Many patients are seen only once. Various efforts have been made to diagnose opportunistic onychomycosis more promptly, extracting maximal information from a single sample rather than procuring successive samples. Walshe and English (42) recommended considering any fungus causal if (i) compatible elements were detected by direct microscopy and (ii) the fungus grew from 5 or more of 20 inoculum pieces (that is, pieces of nail material planted on fungal growth medium) in the absence of a dermatophyte. This criterion was based on the premise that an established nail invader would consistently colonize a substantial proportion of the nail material, whereas contaminants would usually consist of one or a few scattered propagules, with any consistency being coincidental and hence unlikely. The criterion was later restricted to filamentous fungi by English (11), since widely dispersed yeast contamination had been found to be common. This amended version has been employed in numerous studies over the years (1, 22, 23), has been recommended in reviews (9, 15, 19, 26, 30), and is routinely used in many laboratories.

English and Atkinson (12) referred to the inoculum count criterion as “arbitrary” but continued to recommend it for lack of any better alternative. In the intervening years, the criterion has never been subjected to a statistical validation study. The present investigation attempts to remedy this deficiency by determining statistically the extent to which any criterion based on counting of culture-positive inoculum pieces correlates with actual opportunistic dermatophytosis, diagnosed using gold standard successive-isolation procedures for untreated patients who were repeatedly followed up.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient selection and sampling.

Consecutive, consenting patients were entered into the study when they met the following criteria: (i) they were found to have abnormal (i.e., potentially fungally invaded) toenails on visual examination, (ii) they were scheduled to return to the dermatologist's office on subsequent occasions for evaluation of other conditions relating neither to mycosis nor to psoriasis or any immunodeficiency, and (iii) they declined treatment of any onychomycosis discovered in the course of the study for the duration of the study period, used no antifungal drugs during the study period, and had not used antifungal drugs of any kind in the 6 months prior to the study period.

Sampling was done with a sterile no. 15 scalpel blade or curette according to standard procedures (43). The abnormal appearing area of nail to be sampled was disinfected with ethanol, and superficial material was scraped away and discarded before deeper material was collected for fungal analysis. Partitioned sampling was conducted as outlined by Gupta and Summerbell (18) so that areas showing different subcategories of onychomycosis (e.g., superficial white onychomycosis [SWO] or distal-lateral subungual onychomycosis [DLSO]) were analyzed separately.

Laboratory methodology.

Methods for direct microscopy and fungal isolation were those outlined in detail by Summerbell and Kane (37). The techniques were modified to facilitate inoculum counting as follows. Five inoculum pieces of approximately 0.5 to 1 mm2 were plated, well separated from each other, on each of three isolation media: (i) Sabouraud agar amended with a mixture of 100 μg of cycloheximide ml−1, 100 μg of chloramphenicol ml−1, and 50 μg of gentamicin ml−1 (CCG), (ii) CEA medium (37) plus CCG, and (iii) as a cycloheximide-free medium, Littman oxgall agar (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) with 100 μg of streptomycin ml−1. Note that the specific amount of cycloheximide used in the CCG mixture slows down but does not suppress the growth of the non-Scytalidium agents of opportunistic onychomycosis. Media were examined after 7, 14, and 21 days of growth at 28°C.

Each filamentous fungal colony growing from the inoculum pieces was identified at least to genus level, whether or not it belonged to a species previously known as an agent of opportunistic onychomycosis. In cases where more than 15 colonies of a fungus grew, usually because of seeding by fine nail dust during planting of the inoculum pieces, the number of colonies counted was limited to 15. In cases where fast-growing colonies overgrew nearby colonies or inoculum pieces and the number of colonies was unclear, the number counted was the minimum number that could be definitely ascertained. Yeasts were not included in this study, although their presence was noted separately where appropriate for patient diagnosis.

Most fungi were identified to species level. Acremonium spp. were not, but cases were judged significant only if subsequent isolates showed sufficient micromorphological consistency with initial isolates that conspecific status was considered to have been ascertained. The species identity of these difficult organisms will be dealt with in a separate study.

Records were maintained for each patient during long-term follow-up. Most patients returned for three or more repeat analyses at 2- to 6-month intervals; some returned on eight or more such occasions. For each patient, successive records were examined, and when a distinct pattern of fungal isolation became clear, the patient was classified. Those who grew a dermatophyte at least once but did not consistently grow any particular mold after two or more visits were classed as dermatophytosis patients. Those who grew a particular mold consistently on two or more successive occasions (that outgrowth being preceded by observation of consistent filaments by direct microscopy at least once), and continued to grow the same mold consistently thereafter from the same nail (e.g., left hallux) and nail stratum (i.e., distal/subungual or superficial), without growing a dermatophyte on any occasion, were classified as opportunistic onychomycosis patients. Those who grew a dermatophyte on one or more occasions, and also grew a mold with the same consistency, site specificity, and direct microscopic verifiability as indicated for opportunistic onychomycosis, were classed as mixed-infection patients. Patients who grew neither a dermatophyte nor a consistent mold, and who were negative for fungal filaments by direct microscopy, were classed as uninfected. A holding category of patients who could not be definitively assigned (e.g., patients with filaments seen by direct microscopy but no dermatophyte or consistent mold grown after three or more visits) was maintained pro tempore but was not included in the analysis at the end of the study. Patients were classified only when both the dermatologist (A.K.G.) and the mycologist (R.C.S.) were completely satisfied as to their correct status.

Inoculum counts from the first two patient visits were recorded in a database. Different nails and strata (DLSO and SWO) were recorded separately. The organisms producing the counts were recorded as either significant or insignificant. It should be stressed that this judgment was made on a case-by-case basis, so that isolation of an organism like Scopulariopsis brevicaulis might be judged significant in one patient, based on the criteria given above, but insignificant in other patients. Colony counts of significant organisms obtained in the third and subsequent samplings were not used in analysis. This was primarily because in some SWO cases sampling alone appeared to strongly decrease the amount of infected material present on subsequent visits. Moreover, the study was conceived as shedding light on the significance of colony counts obtained in initial patient consultations, rather than over the long-term. To maintain the paired system of initial and subsequent visits, count values of zero were included in statistics for both significant and insignificant organisms, where an organism was found only once in the first and second samples.

In some cases, direct microscopy of the nail material obtained in the initial patient consultation evinced no fungal elements, but the accompanying specimen grew an organism recognized as significant through subsequent analyses (including at least one later demonstration of fungal elements by direct microscopy). The results from these initial “KOH-negative” visits, as well as those from initial visits where direct KOH microscopy gave positive results, were analyzed separately. The rationale was to determine if colony counts at some level could successfully predict true infection even in cases where the initial KOH report was fortuitously negative.

Statistical analysis.

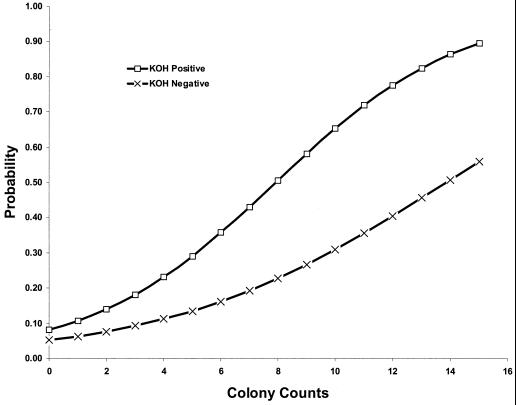

To determine statistically the extent to which a criterion based on counting of culture-positive inoculum pieces could accurately predict true infections, a maximum-likelihood logistic regression model was analyzed. For the combined opportunistic onychomycotic agents, a model was developed in which the onychomycosis classification (i.e., significant or insignificant) served as the criterion measure and the mycological colony count served as the predicting variable. Using the logistic regression model expressed by the equation probability (event) = 1/[1 + e−(B0 + B1X)], where B0 and B1 were the regression coefficients estimated from the data and X was the inoculum count, the probability of a significant classification was estimated. For inoculum counts of 0 through 15, event probabilities were calculated and presented in Fig. 1 for KOH-negative and KOH-positive visits. Further, basic descriptive sample statistics were calculated to examine differences in inoculum counts between significant and insignificant classified organisms. Two sample parametric (i.e., t test) and nonparametric (Wilcoxon rank sum test) analyses were performed to determine if inoculum count differences were statistically significant.

FIG. 1.

Logistic regression analysis indicating the probability of predicting a true positive case of opportunistic onychomycosis based on a given number of nail specimen pieces positive for outgrowth of fungus in culture in the initial patient examination. Fifteen specimen pieces are planted per examination. Curves are given both for specimens positive for fungal filaments by direct microscopic (KOH) analysis in the initial examination and for specimens initially negative for fungal filaments by direct microscopy.

RESULTS

In all, repeated sampling of 473 patients (mean age, 64; standard deviation, ± 15 years) yielded 86 definitively established cases of opportunistic onychomycosis, including both sole-agent and mixed infections. The species and their frequencies are given in Table 1. A surprisingly low proportion of the cases (20 of 86) evinced a coexisting dermatophytosis on the same nail or another nail even after extended study. Two patterns appeared (Table 2): species such as Aspergillus spp. and S. brevicaulis mainly infected hallux nails and were recovered from DLSO-like infections; Acremonium spp. and Onychocola canadensis infected a higher proportion of nonhallux nails and were involved in most of the SWO cases seen. Acremonium spp. in particular showed a distinctive pattern: they infected nonhallux nails in 18 cases and caused SWO in 16 of these. In hallux nails, however, they were frequently associated with DLSO, causing SWO in only 7 of 21 cases. All the fungi together were involved in only three cases of DLSO-like infection of nonhallux nails.

TABLE 1.

Fungi isolated as repetition-proven agents of opportunistic onychomycosis and mixed infection

| Agent | Total no. of cases (male/female) | No. of cases of anychomycosis mixed with dermatophyte infectiona

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (male/female) | Same nail and stratum | Different nail and stratum | ||

| Acremonium spp. | 34 (28/6) | 5 (5/0) | 2 | 3 |

| Arachnomyces sp. | 1 (1/0) | |||

| Aspergillus nidulans | 1 (1/0) | |||

| Aspergillus sydowii | 9 (5/4) | 2 (2/0) | 2 | |

| Aspergillus terreus | 2 (1/1) | 2 (1/1) | 2 | |

| Aspergillus versicolor | 4 (2/2) | 1 (1/0) | 1 | |

| Fusarium oxysporum | 3 (2/1) | 1 (1/0) | 1 | |

| Fusarium solani | 5 (3/2) | |||

| Onychocola canadensis | 5 (2/3) | 1 (1/0) | 1 | |

| Scopulariopsis candida | 1 (1/0) | |||

| Scopulariopsis brevicaulis | 21 (17/4) | 8 (8/0) | 7 | 1 |

| Total | 86 (63/23) | 20 (19/1) | 14 | 6 |

Strata considered are superficial nail (SWO cases) and subungual nail (DLSO). Our study did not distinguish infection of the nail mediostratum from DLSO.

TABLE 2.

Distribution of significant nondermatophyte organisms in nail infection

| Organism and infection | No. of infections

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Hallux | Nonhallux | Total | |

| Acremonium spp. | |||

| DLSO | 14 | 2 | 16 |

| SWO | 7 | 16 | 23 |

| Total | 21 | 18 | 39a |

| Aspergillus sydowii | |||

| DLSO | 6 | 0 | 6 |

| SWO | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Total | 8 | 2 | 10 |

| Onychocola canadensis | |||

| DLSO | 4 | 1 | 5 |

| SWO | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 4 | 2 | 6 |

| Scopulariopsis brevicaulis | |||

| DLSO | 19 | 0 | 19 |

| SWO | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Total | 19 | 2 | 21 |

Sums exceed total case numbers from Table 1 where organisms cause both DLSO and SWO infection in the same patient.

More males than females were found to have opportunistic onychomycosis (Table 1), as was expected based on other epidemiology studies which demonstrated that onychomycosis occurred more frequently in males than in females. The proportion of males and females with opportunistic onychomycosis did not differ significantly from the proportion of males and females with dermatophyte infection (data not shown). On an organism-by-organism basis (opportunistic organisms only), there were no significant differences in male-female distribution of infection. Only 1 in 20 infections judged to be a combination infection along with a dermatophyte was found in a female patient, although 51 of 171 single infections (nondermatophyte or dermatophyte only) occurred in female patients.

Studies of all mold inoculum counts revealed a strongly statistically supported difference (P < 0.0001) between counts from significant and insignificant isolations associated with positive direct microscopy (KOH-positive) results (Table 3). The average count for significant organisms was 8.6 positive inocula, compared to an average of 1.5 positive inocula for insignificant organisms. Since various mold fungi may be strongly biologically different, closely related species groups large enough to permit meaningful statistical analysis were analyzed separately. In all these genus level groups studied, e.g., Aspergillus, inoculum counts of significant organisms from cases with positive direct microscopy were strongly statistically different from counts of insignificant organisms.

TABLE 3.

Inoculum counts from significant isolations of agents of opportunistic onychomycosis compared to counts from insignificant isolations

| Organism | KOH status | No. of samples growing organism

|

Mean count for 1st and 2nd visits

|

Pb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Significanta | Insignificanta | Significant | Insignificant | |||

| Acremonium spp. | + | 57 | 9c | 8.4 | 1.6 | 0.004 |

| − | 26 | 29 | 4.5 | 1.9 | 0.074 | |

| Aspergillus spp. | + | 22 | 83 | 7.0 | 1.6 | 0 |

| − | 12 | 136 | 3.7 | 1.4 | 0.032 | |

| Fusarium spp. | + | 11 | 35 | 6.4 | 2.4 | 0.001 |

| − | 6 | 28 | 4.7 | 0.6 | 0.026 | |

| Scopulariopsis spp. | + | 32 | 44 | 9.3 | 1.3 | 0 |

| − | 13 | 64 | 4.2 | 1.6 | 0.331 | |

| All molds | + | 137 | 302 | 8.6 | 1.5 | 0 |

| − | 61 | 440 | 4.5 | 1.4 | 0 | |

“Significant” and “insignificant” indicate cases where the nondermatophytes were retrospectively judged on the basis of long-term, multisample patient records to have had the indicated status at the time they grew out from nail samples.

Probability of chance alone explaining difference between significant and insignificant cases according to the Wilcoxon rank sum test.

Note that in isolations judged insignificant although filaments were present in KOH, filaments were normally consistent with nongrowing dermatophytes; these were confirmed as such in later cultures from the same patient.

Statistical support was much lower in cases where no fungal elements were seen in direct microscopy of the initial specimen. (Note, however, that in all such cases deemed significant, positive direct microscopy was obtained with at least one later specimen.) Even though average inoculum counts were close to 4 for significant organisms, and to 1 for insignificant organisms, the difference for individual fungal genera was not significant or was only marginally (P < 0.05) significant. Only in the much larger sample of all molds studied was a high level of significance (P < 0.0001) achieved.

The finding that, under given circumstances, inoculum counts of opportunistic onychomycosis agents in significant isolations strongly differed from those obtained in insignificant isolations did not itself suggest a cutoff threshold where counts became high enough to reliably indicate etiologic status for the isolated molds. In an attempt to generate a statistically valid analogue of the Walshe and English 5-of-20 rule, logistic regression analysis was performed on all the molds isolated and on individual groups. Because the counts obtained were strongly bimodal, with mainly low counts for insignificant isolations, and many counts around 15 of 15 in significant isolations, regression lines for the numerically smaller groups, e.g., Fusarium, were invalid or of dubious utility. However, a well-supported regression line was generated for all molds combined. It is shown in Fig. 1. As can be seen, in cases where direct microscopy is positive, a known opportunistic onychomycosis agent grown from 15 of 15 positive inocula has a nearly 90% probability (89.7%) of being etiologic. The analogous probability associated with 14 positive inocula is 86.5%, that associated with 13 positive inocula is 82.6%, and so on. On the other hand, translating the Walshe and English criteria (5 of 20 = 25% positive inoculum pieces = 4 of 15 positive inoculum pieces) into the planting practices of the present study gives a criterion that will correctly predict true infection only 23.2% of the time and will otherwise be false-positive. Similarly, a finding of 5 out of 15 positive inoculum pieces correctly predicts true infection only 29.1% of the time. For microscopy-negative samples, despite the generality that inoculum count overall correlates highly significantly with true infection, even a positive inoculum count of 15 of 15 has only a 56.1% probability of correctly predicting an infection in an individual case.

Examination of the distribution of the count data for KOH-positive specimens (Table 4) shows that, while high counts in insignificant isolations were relatively rare, low counts in significant cases were relatively common. In fact, the appearances of low counts and high counts are nearly equal in significant cases. Fusarium and Aspergillus species were particularly likely to give high colony counts in cases where they were insignificant. In the case of Scopulariopsis, no insignificant isolation gave an initial inoculum count of 11 or greater, and only three insignificant isolations yielded counts between 6 and 10. None of the insignificant isolations of Acremonium produced a count higher than 5.

TABLE 4.

Distribution of numbers of cases yielding low, moderate, and high inoculum counts from specimens with positive direct microscopy results

| Organism | No. of low counts (0–5 colonies)

|

No. of moderate counts (6–10 colonies)

|

No. of high counts (11–15 colonies)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Significanta | Insignificant | Significant | Insignificant | Significant | Insignificant | |

| Acremonium | 25 | 9 | 6 | 26 | ||

| Aspergillus | 11 | 79 | 5 | 1 | 6 | 3 |

| Fusarium | 5 | 31 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Scopulariopsis | 13 | 41 | 1 | 3 | 18 | |

| Totalb | 57 | 160 | 17 | 5 | 62 | 6 |

“Significant” and “insignificant” indicate cases where the nondermatophytes were retrospectively judged on the basis of long-term, multisample patient records to have had the indicated status at the time they grew out from nail samples.

Includes some fungi, such as O. canadensis, not listed separately.

DISCUSSION

The above analysis makes it clear that the specific inoculum-counting criterion recommended by Walshe and English (42) cannot be validly used. This criterion—namely, that 5 or more of 20 inocula from a KOH-positive sample consistently growing the same mold should be taken as an indicator of opportunistic onychomycosis—yields a false-positive rate of at least 75%, in comparison to results determined by long-term follow-up consistent with Koch's first postulate.

On the other hand, there is a very strong statistical correlation between high inoculum counts (11 or more) and true opportunistic onychomycosis when the sample is KOH positive. The probability that a colony count of 11 or more is associated with a significant opportunistic onychomycosis is greater than 70% (Fig. 1). All Acremonium counts above 5 (n = 32) in direct-microscopy-positive cases were associated with verified infections (Table 4). This was not true in direct-microscopy-negative cases (data not shown), where insignificant isolations gave Acremonium counts of 9 and 15. As a predictor of true opportunistic onychomycosis in a direct-microscopy-positive nail, the use of high counts, especially a count of 15, has a low false-positive rate but a high false-negative rate. In comparison to other species, Fusarium and Aspergillus species were more likely to give high colony counts in cases where they were insignificant (Table 4): thus, three of nine direct-microscopy-positive cases yielding Aspergillus inoculum counts of 11 or greater were insignificant, while three of five such Fusarium isolations were insignificant. In the case of Scopulariopsis, although no insignificant isolation gave an initial inoculum count of 11 or greater, three such insignificant isolations did yield counts between 6 and 10.

Given the arduous and expensive nature of follow-up studies, it is tempting to use this information to advantage in interpreting initial laboratory results. Firstly, however, it must be stated that the degree of interest in this matter naturally depends on whether any treatment issue depends on fungal identification. Some controversy attends this topic, but it is certainly well established that fungi in the order Microascales, including the nail-infecting Scopulariopsis species, and fungi in the order Hypocreales, including the nail-infecting Fusarium and Acremonium species, show distinctive and often (although not always) unpromising responses in vitro to currently used oral antifungals, including fluconazole, griseofulvin, terbinafine, and itraconazole (2, 5, 8, 16, 24, 27, 29, 33, 39, 41). Although the situation in vivo may be more complex, as is suggested by apparent cure of some Fusarium and Scopulariopsis onychomycosis by itraconazole or terbinafine therapy (8, 14, 28, 40), there appears to be good prima facie justification for a dermatologist wanting to know whether his or her patient is truly infected by one of these normally drug resistant organisms.

In combination with partitioned sampling (18), inoculum counting may be used to make critical decisions about whether or not to treat infections. For example, in the case of a patient who grows Trichophyton rubrum and one Acremonium colony from a destructive DLSO of the right hallux but grows 15 Acremonium colonies from relatively innocuous, microscopically verified SWO of the right third nail, a decision may reasonably be made to treat the former agent and ignore the latter, which is likely to be refractory in any case. If the SWO on the right third nail then persists after oral antifungal treatment resolves the infection in the hallux nail, this will not be taken as an adverse indication.

Recent, very elegant studies by Piérard and collaborators (3, 25) have shown that the rigorous documentation of nondermatophytic onychomycosis can be accomplished from a single nail specimen by the use of high-technology techniques such as flow cytometry and differential immunohistochemistry. Such techniques, however, are scarcely practical for routine diagnosis: for example, maintenance of a substantial library of specially prepared immunological reagents is necessary for the latter technique. On the other hand, histopathology of a nail clipping or a nail biopsy specimen may reveal fungal filaments within the nail plate indicative of onychomycosis. However, this technique does not allow for the causative organism to be identified.

As the results of this study show, no inoculum count can give an ironclad assurance, or even a conventionally reassuring statistical probability of 95 or 99%, that a patient has an opportunistic onychomycosis. Long-term follow-up is clearly to be scientifically recommended over inoculum counting as a device for separating valid opportunistic onychomycosis from suggestive contamination events. Yet, if a patient is unlikely to submit to follow-up studies, or if a health care system does not make them practicable, then the knowledge that the patient's initial specimen showed, for example, direct-microscopy-confirmed onychomycosis with a 90% probability of Acremonium etiology, is unlikely to be ignored. The counting of inocula in possible cases of opportunistic onychomycosis may not be sufficient to force the physician's decision about a case, but it nonetheless significantly adds to his or her base of relevant information. Therefore, we recommend that when a laboratory isolates a known agent of opportunistic onychomycosis from a microscopy-positive nail, the inoculum count be reported as well as the number of inocula originally planted.

A high inoculum count of an opportunistic nondermatophyte from a microscopy-negative nail should indicate to the dermatologic mycology laboratory that the direct-microscopy result of the nail needs to be painstakingly reexamined, possibly using a larger than usual amount of specimen. Laboratory observation showed that obtaining a positive direct-microscopy result on the initial visit, as well as subsequent visits, was problematic. We carried out a subsidiary study on 20 patient samples showing a negative direct-microscopy result on initial examination and heavy outgrowth of a known opportunistic onychomycosis agent in culture. Acremonium, Aspergillus, and Fusarium cases were included in the sample. Residual scraping material that had not been included in initial KOH or culture studies was exhaustively examined microscopically in a search for fungal elements. In 18 of 20 cases, such elements were found, and when found, they were seen to be heavily invested in a small proportion of scraping fragments. Because positive scraping pieces were uncommon in the samples, and because they were conspicuously heavily colonized when found, it appeared relatively unlikely that they could have been missed by laboratory reading error alone in the initial examination. To avoid a begging-the-question logical error (because cases with a high inoculum count in primary culture were selectively studied), the results of this ancillary study were not included in the main study. Obtaining a positive direct-microscopy result was particularly problematic with SWO cases. It was observed in the dermatology clinic that the “islands” of SWO on the patient's nail were sometimes scattered within more extensive regions of normal nail. Therefore, even relatively targeted scraping often included a preponderance of normal nail material. It seemed possible that in the laboratory, a typical subsample of scraping material extracted for direct microscopy might easily, by chance alone, contain entirely normal nail material. However, because positive portions of scraping material were typically found to be heavily loaded with fungal material, a strong outgrowth in culture might still be obtained.

Reexamination is, of course, possible only when some of the specimen is retained after initial direct microscopy and culture have been completed. Policies of expending the entire submitted specimen on initial microscopy and culture, even when the submitted quantity is large, must be discouraged. Very small initial specimen amounts do not permit a three-way split of the material, but larger specimens may profitably be apportioned in this way. As Kane (20, 21) has shown, residual specimen may also be used for performing scatterplate culture techniques in cases where antibiotic-polyresistant bacteria or mold contaminants overgrow the initial cultures. A significant number of false culture-negative analyses may be avoided in this way, particularly as extended desiccation at temperatures up to 30°C is not harmful to dermatophytes in skin and nail specimens (31, 32) but may diminish the burden of antibiotic-polyresistant bacteria. An initial KOH report indicating no fungal elements present should be followed up by a corrected report if such elements are later found, and dermatologists should realize that under certain circumstances, such a correction does not reflect negatively on the performance of the laboratory. It would not be possible or efficient to routinely examine the quantity of material that must be examined in order to detect the heterogeneously distributed positive elements in some cases of opportunistic onychomycosis. Regular laboratory procedures are optimized for the much more common dermatophyte infections, and the relatively uncommon cases of opportunistic onychomycosis may occasionally require the use of some differing protocols.

The obtaining of low in vitro counts from significant opportunistic onychomycosis may well be tied to sampling strategies and different presentations of the nail infection. A subungual sampling technique aimed at DLSO may include little or no material from SWO on the same nail. A truly invasive organism, therefore, may be poorly represented in the sample. (The physician, however, may have decided in advance that the SWO was an insignificant problem in the case at hand and therefore was not the target of the investigation, despite the known frequent association between Trichophyton mentagrophytes and SWO [44, 45].) Likewise, a strategy of mixing samples from several of a patient's nails into the same shipping packet might strongly dilute the occurrence of an etiologic agent, or mix the agents of two different opportunistic onychomycoses together, making the nails simply appear contaminated. One patient in the present study had Aspergillus terreus consistently in one hallux nail and O. canadensis in the other, as well as in two adjacent nails. This case would have been difficult to understand without separate sampling of the nails. In cases where a patient bore only a few flecks of SWO, nail surface scraping or clipping would be expected to yield small counts of the causative agent, simply due to the degree of dilution by normal nail. Even moderately heavy appearing SWO often contains a substantial admixture of normal nail surface, as mentioned above. The physician's clinical notes may aid in the interpretation of inoculum counts appearing on ensuing laboratory reports.

In other cases, low inoculum counts from potentially significant organisms may be difficult to interpret without follow-up. It is always possible with mold infection, as with dermatophytosis, to sample fortuitously a portion of the lesion that is suboptimal for laboratory investigation, whether the area sampled contains effete inoculum, or whether it is marginal and is not yet heavily colonized. The laboratory study of dermatophytosis is constantly rendered difficult by the failure of true-positive samples to contain living inoculum in 15 to 25% of cases (4, 6, 7, 13, 32, 34). In light of such possibilities, it may be unrealistic to expect low mold inoculum counts to be as readily interpretable as high counts are.

Inoculum counting may be most valuable in conjunction with well-directed sampling, and such optimal sampling may require considerable skill and experience. Given the probabilistic complexity of inoculum counting and the technical refinement needed to accompany it, clinicians preferring simple, unambiguous laboratory results may be advised to recall suspected nondermatophyte onychomycosis patients, where indicated, for further sampling according to gold standard procedures.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Sal Albreish and Ursula Bunn for extensive assistance in counting inocula and Maria Witkowska for assistance with cultures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Achten G, Wanet-Rouard J. Onychomycoses in the laboratory. Mykosen. 1978;23(Suppl. 1):125–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aguilar C, Pujol I, Guarro J. In vitro antifungal susceptibilities of Scopulariopsis isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:1520–1522. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.6.1520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arrese J E, Piérard-Franchimont C, Greimers R, Piérard G E. Fungi in onychomycosis. A study by immunohistochemistry and dual flow cytometry. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 1995;4:123–130. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clayton Y M. Clinical and mycological diagnostic aspects of onychomycoses and dermatomycoses. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1992;17:37–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1992.tb00276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clayton Y M. Relevance of broad-spectrum and fungicidal activity of antifungals in the treatment of dermatomycoses. Br J Dermatol. 1994;130(Suppl. 43):7–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1994.tb06084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crespo Erchiga V, Casañas Carrillo C, Ojeda Martos A, Crespo Erchiga A, Vera Casaño A, Sánchez Fajardo F. Examen directe versus culture. Etude sur 1115 cas de dermatomycoses. J Mycol Med. 1999;9:154–157. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davies R R. Mycological tests and onychomycosis. J Clin Pathol. 1968;21:729–730. doi: 10.1136/jcp.21.6.729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Doncker P, Scher R K, Baran R L, Decroix J, Degreef H J, Roseeuw D I, Havu V, Rosen T, Gupta A K, Pierard G E. Itraconazole therapy is effective for pedal onychomycosis caused by some nondermatophyte molds and in mixed infection with dermatophytes and molds: a multicenter study with 36 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36:173–177. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(97)70275-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeGreef H. Onychomycosis. Br J Clin Pract Suppl. 1990;71:91–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DiSalvo A F, Fickling A M. A case of non-dermatophytic toe onychomycosis caused by Fusarium oxysporum. Arch Dermatol. 1980;116:699–700. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.English M P. Nails and fungi. Br J Dermatol. 1976;94:697–701. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1976.tb05171.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.English M P, Atkinson R. An improved method for the isolation of fungi in onychomycosis. Br J Dermatol. 1973;88:237–241. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1973.tb07540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gentles J C. Laboratory investigations of dermatophyte infections of nails. Sabouraudia. 1971;9:149–152. doi: 10.1080/00362177185190331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gianni C, Cerri A, Crosti C. Unusual clinical features of fingernail infection by Fusarium oxysporum. Mycoses. 1997;40:455–459. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.1997.tb00184.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greer D L. Evolving role of nondermatophytes in onychomycosis. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:521–524. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1995.tb02942.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guarro J, Gams W, Pujol I, Gene J. Acremonium species: new emerging fungal opportunists—in vitro antifungal susceptibilities and review. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25:1222–1229. doi: 10.1086/516098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gupta A K, Jain H C, Lynde C W, Watteel G N, Summerbell R C. Prevalence and epidemiology of unsuspected onychomycosis in patients visiting dermatologists' offices in Ontario, Canada—a multicentre survey of 2001 patients. Int J Dermatol. 1997;26:783–787. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.1997.00349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gupta A K, Summerbell R C. Combined distal and lateral subungual and white superficial onychomycosis in the toenails. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:938–944. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70250-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haneke E. Fungal infections of the nail. Semin Dermatol. 1991;10:41–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kane J. The biological aspects of the Kane/Fischer system for identification of dermatophytes. In: Kane J, Summerbell R C, Sigler L, Krajden S, Land G, editors. Laboratory handbook of dermatophytes. Belmont, Calif: Star Publishing; 1997. pp. 81–129. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kane J, Summerbell R C. Dermatologic mycology: examination of skin, nails and hair. In: Kane J, Summerbell R C, Sigler L, Krajden S, Land G, editors. Laboratory handbook of dermatophytes. Belmont Calif: Star Publishing; 1997. pp. 33–44. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lim J T-E, Chua H C, Goh C L. Dermatophyte and non-dermatophyte onychomycosis in Singapore. Australas J Dermatol. 1992;33:159–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-0960.1992.tb00110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McAleer R. Fungal infections of the nails in Western Australia. Mycopathologia. 1981;73:115–120. doi: 10.1007/BF00562601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nolting S, Brautigam M, Weidinger G. Terbinafine in onychomycosis with involvement by non-dermatophytic fungi. Br J Dermatol. 1994;130(Suppl. 43):16–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1994.tb06088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Piérard G E, Arrese J E, Pierre S, Bertrand C, Corcuff P, Leveque J L, Pierard-Franchimont C. Diagnostic microscopique des onychomycoses. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1994;121:25–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ramesh V, Reddy B S N, Singh R. Onychomycosis. Int J Dermatol. 1983;22:148–152. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1983.tb03352.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Richardson M D. Effect of Lamisil and azole antifungals in experimental nail infection. Dermatology. 1997;194(Suppl. 1):27–31. doi: 10.1159/000246181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Romano C, Miracco C, Difonzo E M. Skin and nail infections due to Fusarium oxysporum in Tuscany, Italy. Mycoses. 1998;41:433–437. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.1998.tb00369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Romano C, Presenti L, Massai L. Interdigital intertrigo of the feet due to therapy-resistant Fusarium solani. Dermatology. 1999;199:177–179. doi: 10.1159/000018233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Singh S M. Non-dermatophytic onychomycosis: a review. In: Hasija S K, Bilgrami K S, editors. Perspectives in mycological research. II. 1990. pp. 293–310. Prof. G. P. Agarwal Festschrift. Today & Tomorrow's Printers and Publishers, Delhi, India. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sinski J T, Moore T M, Kelley L M. Effect of moderately elevated temperatures on dermatophyte survival in clinical and laboratory-infected specimens. Mycopathologia. 1980;71:31–35. doi: 10.1007/BF00625310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sinski J T, Wallis B M, Kelley L M. Effect of storage temperature on viability of Trichophyton mentagrophytes in infected guinea pig skin scales. J Clin Microbiol. 1979;10:841–843. doi: 10.1128/jcm.10.6.841-843.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Speeleveld E, Gordts B, van Landuyt H W, De Vroey C, Raes-Wuytack C. Susceptibility of clinical isolates of Fusarium to antifungal drugs. Mycoses. 1996;39:37–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.1996.tb00081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Suarez S M, Silvers D N, Scher R K, Pearlstein H H, Auerbach R. Histologic evaluation of nail clippings for diagnosing onychomycosis. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:1517–1519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Summerbell R C. Epidemiology and ecology of onychomycosis. Dermatology. 1997;194(Suppl. 1):32–36. doi: 10.1159/000246182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Summerbell R C. Non-dermatophytic fungi causing onychomycosis and tinea. In: Kane J, Summerbell R C, Sigler L, Krajden S, Land G, editors. Laboratory handbook of dermatophytes. Belmont, Calif: Star Publishing; 1997. pp. 213–259. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Summerbell, R. C., and Kane J. 1997. Physiological and other special tests for identifying dermatophytes, p. 45–77. In J. Kane, R. C. Summerbell, L. Sigler, S. Krajden, and G. Land (ed.), Laboratory handbook of dermatophytes. Star Publishing, Belmont, Calif.

- 38.Summerbell R C, Kane J, Krajden S. Onychomycosis, tinea pedis and tinea manuum caused by non-dermatophytic fungi. Mycoses. 1989;32:609–619. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.1989.tb02192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sutton D A, Fothergill A W, Rinaldi M G. Guide to clinically significant fungi. Baltimore, Md: Williams & Wilkins; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tosti A, Piraccini B M, Lorenzi S. Onychomycosis caused by nondermatophytic molds: clinical features and response to treatment of 59 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:217–224. doi: 10.1016/S0190-9622(00)90129-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Van Cutsem J. The in vitro antifungal spectrum of itraconazole. Mycoses. 1989;32(Suppl. 1):7–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Walshe M M, English M P. Fungi in nails. Br J Dermatol. 1966;78:198–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1966.tb12205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weitzman I, Summerbell R C. The dermatophytes. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1995;8:240–259. doi: 10.1128/cmr.8.2.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zaias N. Superficial white onychomycosis. Sabouraudia. 1966;5:99–103. doi: 10.1080/00362176785190181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zaias N. Onychomycosis. Arch Dermatol. 1972;105:263–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]