Abstract

Aim

To explore the literature about services and interventions provided to tween children as the basis for informing future practice and policy.

Background

The tween years (10–13 years) is a period in human development where children experience rapid physical and mental development; their thinking and actions are influenced by peer pressure, risk taking, concerns about their body image, size, and gender, and may become victims to bullying and increasing levels of mental ill-health. It may also be a time of transition between schooling institutions. Despite the multiplicity of these factors, pre-adolescents appear to be receiving little attention from both service providers and policy makers.

Methods

Following the PRISMA reporting guidelines, a systematic search of peer-reviewed papers was conducted between June 2020 and April 2021. Studies were selected by screening their abstracts and titles. In total, 44 articles were included for in-depth analysis. Of these, 17 were randomised studies and 10 were non-randomised, and all were subjected to the assessment of risk of bias using the Review Manager Tool and ROBINS-I Tool respectively.

Data extraction and synthesis

Data was extracted by type of service/intervention/program, country, and type of study/methodology, aim, sample size, age range, and findings. Data synthesis was performed using thematic analysis and content analysis. The results are presented in an outcome summary table highlighting the study's outcomes including the provided programs, their acceptability, and their impacts on factors such as anxiety and depression levels, change of attitude, behavioural control, weight loss, resilience and coping, emotional regulation, self-esteem, and improved well-being.

Conclusion

The majority of programs described in this review reported positive results, and as a result have the potential to make a valuable contribution to future practice, policy, and research involving the tweens.

Keywords: Tween children, Services, Programs, Intervention, Problem, Pre-adolescence, Adolescent

Tween children; Services; Programs; Intervention; Problem; Review.

1. Introduction

Children in their tween years (ages 9 to 14) face numerous problems, yet they receive little attention from service providers and policymakers. A tween is a child between the age of 8 and 12. However, the term "tween" has been synonymously used in this review with terms such as adolescents and pre-adolescents to refer to children aged 10 to 13. Redmond et al. (2016) attested to the argument about tween children needing intervention by stating that "compared with the early years and adolescence, young people in their middle years (ages 8–14 years) have received relatively little attention from policymakers other than in the space of academic achievement, where national curricula are being developed, and a national assessment program is in place (p. xi). There are a lot more problems in tween years that policymakers should pay attention to (Redmond et al., 2016). To start addressing tween problems, states, policymakers, and service designers must move away from solely focusing on improving children's academic performance.

There are numerous reasons why services should give tween children attention. First, ages 10–13 years are a crucial time for developing gender identity (de Vries et al., 2016) and the onset of juvenile delinquency (Ayers and Harry, 2012). Research shows that when interventions are not provided to children who do not identify with their birth-assigned sex and sexual body characteristics, pre-adolescents are at risk of developing body dysmorphic disorder (de Vries et al., 2016; Olvera et al., 2015; Webb et al., 2015). Second, pre-adolescence is a developmental window period where children are at risk of being introduced to drugs, substance abuse, and gambling (Derevensky, 2012; Donovan and Molina, 2014; Gallimberti et al., 2015; Noel, 2019; Rossow and Kuntsche, 2013). In addition, pre-adolescence is a period in human development where children start oppositional and antisocial behaviours (Havighurst et al., 2015) and onset for bullying victimisation (Smith, 2016). Pre-adolescence is also a period where children are at increased risk of becoming obese (Fradkin et al., 2018). Moreover, tween children are at increased risk of being peer pressured to school grade performance (Poddar, 2020); sexual encounters (Milevsky, 2015); may develop playground aggression (Clark et al., 2019); and maybe moved into out-of-home care as a result of neglect (McFarlane, 2018). Additional complexities are those related to peer rejection, risk-taking tendencies, shame, trait flexibility, perfectionism, changes in sleep duration, body image ideation, guilt, and social anxiety (Nader, 2019). These complexities add to the concerns experienced by children in the tween years.

Tween children are also vulnerable to biological changes brought about by hormones during adolescence (Steinberg, 2017). This can cause a developmental shift from viewing parents as important figures in their lives to viewing peers as more important and consequently result in changes in behaviours that may be difficult to manage or are confusing and overwhelming for the growing individual (Guyer et al., 2016). Hormonal changes can also influence the development of antisocial behaviours, crime, and sexual development in adolescence. To address these problems, Steinberg suggested that the best society can do; is "find ways of managing the young person whose raging hormones would invariably lead to difficulties" (p. 9).

In addition, although the literature base is still in need of development, some studies have been undertaken on the effectiveness of services targeting tween children. Good examples of recent reviews include reviews on the programs designed to reduce anxiety and depression (Bastounis et al., 2016; Fenwick-Smith et al., 2018; Johnstone et al., 2018), a review on services provided to curb adolescent's traumatic grief (Greatrex-White and Taggart, 2015), a review of interventions targeting adolescents' alcohol and substance misuse (Hodder et al., 2017), and a review of interventions in communication skills for children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) (Hansen et al., 2017). There have also been review studies on interventions targeting children with ASD about maths interventions (King et al., 2016) and virtual reality interventions (Mesa-Gresa et al., 2018). Other studies have looked into the effectiveness of programs designed to improve affective abilities in adolescents (Lui et al., 2017), their speech (Sugden et al., 2019), and the mental health of pre-adolescents transitioning into high school (Woods and Pooley, 2015). One major limitation of past reviews is their focus on the effect of a single program or service in different contexts. Past reviews tended to describe or present evidence of interventions that can be classified as either psychological, physical, or educational. As a result, no review comprehensively looked at available services, programs, or interventions designed for tween children. In other words, there was gap in systematic reviews on services designed for tween children, and this review aimed to fill that gap.

The current review sought to describe globally available services and programs designed for tween children (see Appendix C). Subsequently, this study aimed to answer these research questions:

-

•

What are current intervention services available for tween children?

-

•

Are interventions designed for tween children effective?

-

•

Do program designers provide interventions that reduce the complexity of tween problems?

2. Methods

A systematic search of peer-reviewed papers published between January 2015 and June 2021 was conducted between June 2020 and June 2021, following the PRISMA reporting guidelines. A number of databases were used. They included the Griffith University Library and the Research Library for access to multidisciplinary global research and data; ProQuest education and Eric databases for access to the literature on services provided in educational settings, including primary schools and grades corresponding to ages 10 to 13 (Webb et al., 2015); SAGE, Taylor and Francis, ProQuest, and Wiley online library databases for access to programs designed by social sciences and humanities professionals; PsychInfo and Scopus databases for access to psychological journals; and lastly the Informit database to access Australian and South-east Asian designed programs. Using a wide range of databases in locating studies ensured that all possible and relevant studies on problems affecting tween children were included.

The Search string used comprised of key terms including ("tween" OR "child∗" OR "adolescent" OR "juvenile" OR "teen∗") AND ("service" OR "care" OR "program∗" OR "treatment" OR "intervention") AND ("age" OR "year") AND "age∗ 10 to 13". To meet the inclusion criteria, studies had to be peer-reviewed, full text online, journal articles, and published in English. Limiting papers to peer-reviewed ensured that only academic papers were included, full text for easy accessibility, Journal articles for access to recently undertaken studies, and published in English for a clear understanding of the contents of articles. The authors limited articles to English published articles as they could not understand any other academic language.

Included studies had to meet the following inclusion criteria: children participants of age 10 to 13 (See Appendix A). Once studies that met the inclusion and exclusion criteria were identified, references of identified studies were used to find additional articles.

The heterogeneity of included studies and the absence of suitable numerical data from most studies excluded the possibility of carrying out a meta-analysis and measuring effect sizes of provided interventions. Instead, thematic and content analysis were used to summarise and analyse the findings of identified studies.

Equally important, the risk of bias within, across, and of individual studies are reported to meet the PRISMA requirement. Moreover, studies had to be grouped into random and non-randomised studies and corresponding analyses of the risk of bias. The risk of bias analysis was undertaken using the Review Manager (RevMan) appraisal tool for randomised studies and the ROBINS-I tool (Sterne et al., 2016) for included non-randomised studies. However, given that the outcome of analysing the risk of bias was extensively reported in this study, the purpose of this study did not change.

3. Results

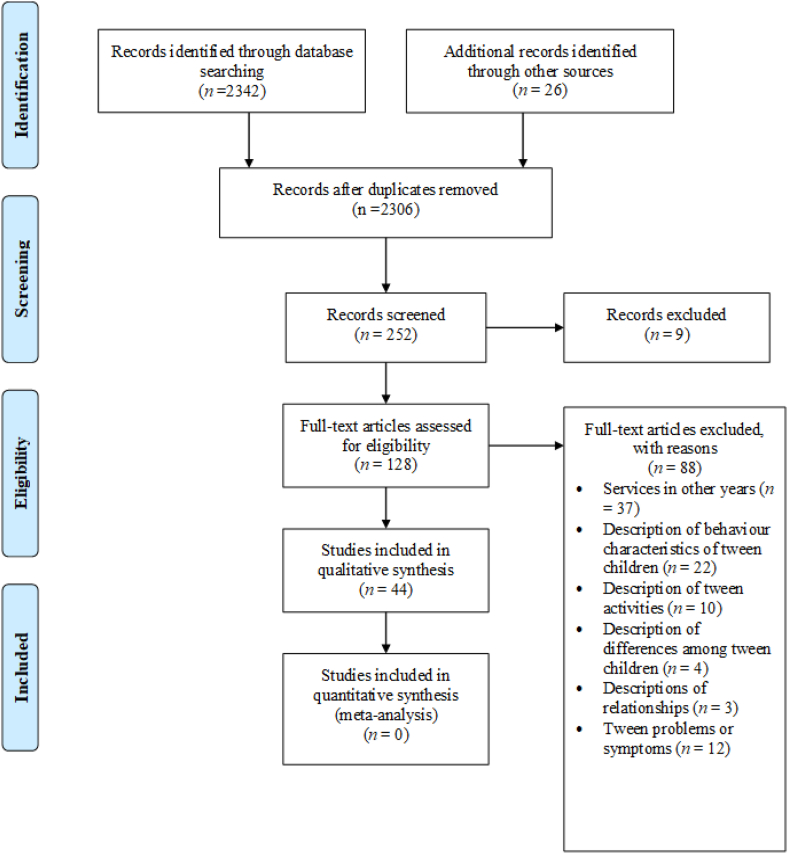

In total, 2342 records were preliminarily identified through the electronic database searching, and 26 additional records were identified through the reference list of articles that met the inclusion criteria. Of these, 2054 were excluded due to not being relevant to the purpose of this study, 88 were excluded with reason, and 44 articles were included for analysis (see Appendix A). Of these, 17 were randomised trials, 10 were non-randomised trials, eight were follow-up surveys, six were descriptive studies, and two were mixed-method studies (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram showing selection process of identified literature.

3.1. Characteristics of included studies

Most studies were undertaken in the United States (n = 7), United Kingdom (n = 6), Australia (n = 5), and the Netherlands (n = 3). While studies were conducted in several other countries, only one study per country was identified. The sample sizes reported in the studies also varied vastly from as small as seven (Burke et al., 2017) to a larger sample of 4631 children (Kim et al., 2020).

Program duration also varied from as little as 24min to as many as 3 hours per session, over 14 sessions (Burn et al., 2019).

Teachers and paediatricians offered the majority of programs. Other personnel who provided services to children included social workers, family therapists, physical therapists, health and medical service practitioners, nurses and paediatricians.

Most of these services were provided in schools, with a few more offered at home, health care centres, telehealth, and summer camps. These programs were categorised under different types of intervention, including physical, academic, child care, after-school program, life skills, summer camp, and intervention with family.

3.2. Risk of bias within studies

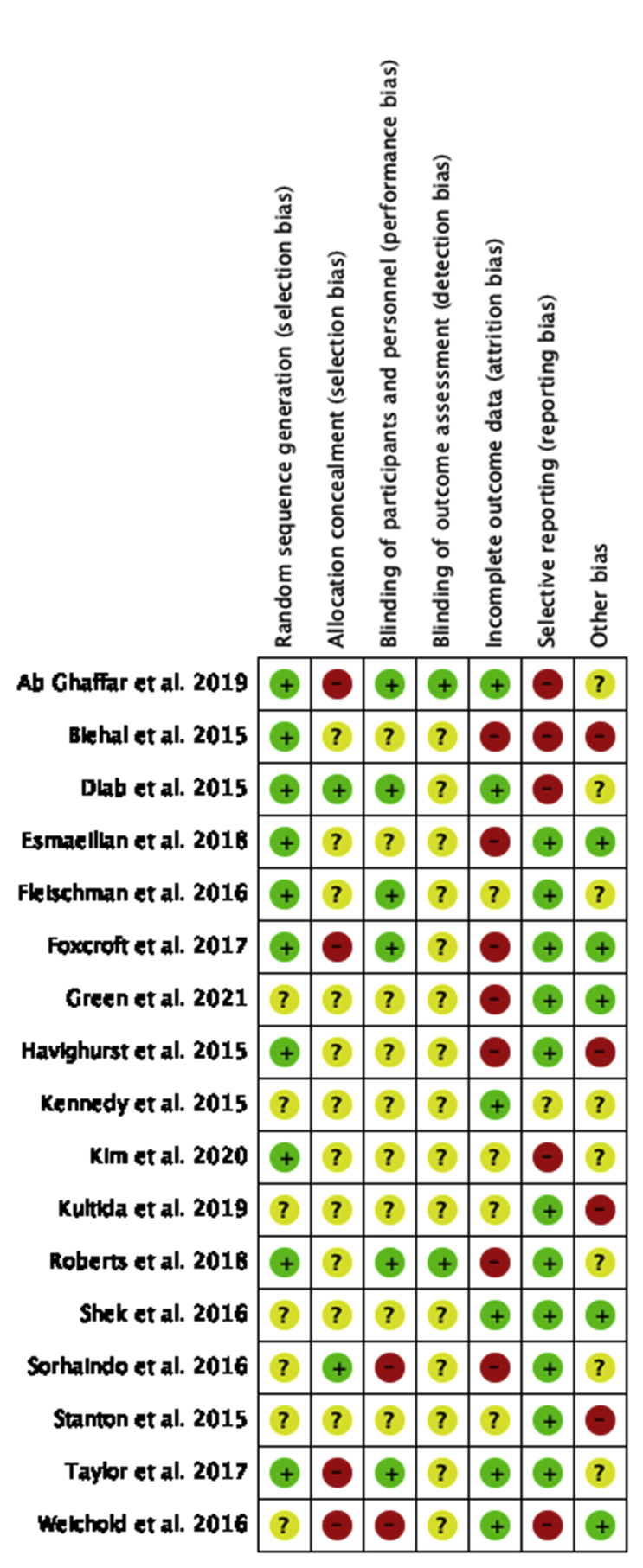

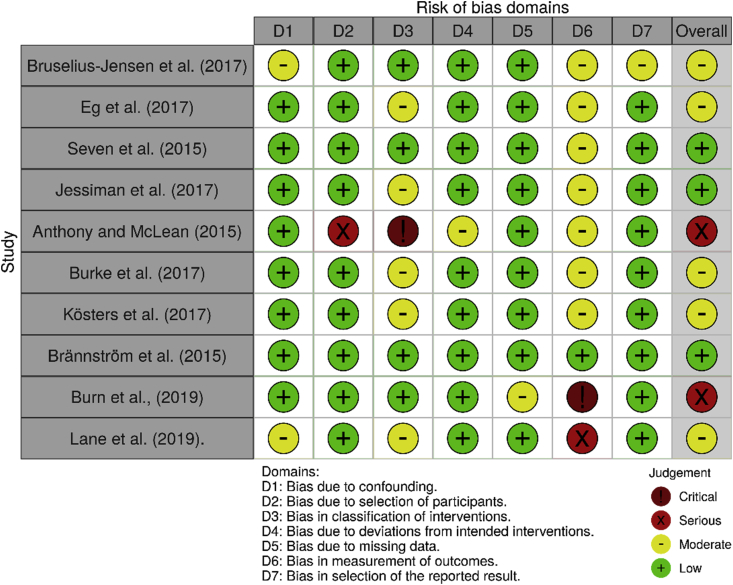

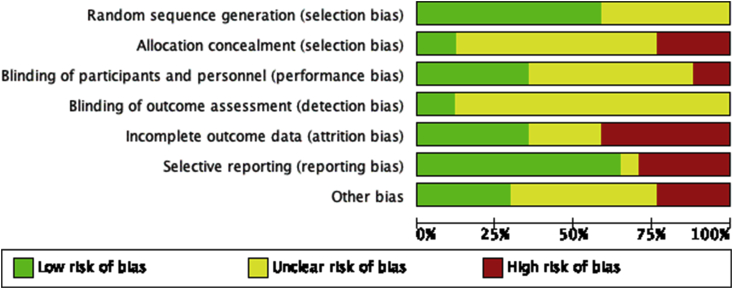

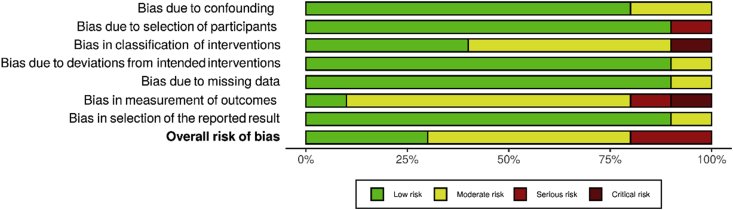

Of the 17 randomised trials, six studies were rated with unclear risk of bias. This is because they failed to mention the type of randomisation used in selecting participants (see Figure 2). Four studies were rated as having high risks of bias due to allocation of participants, 13 classified with unclear risk of bias due to blinding of the outcome, and five studies classified with high risks of bias due to missing data. Assessment of risk for each non-randomised study was used to generate "traffic-light" plots and weighted bar plots using the Robvis visualisation tool (McGuinness and Higgins, 2021). The results are Figures 2 and 3 (see Figures 4 and 5)

Figure 2.

Summary of risk of bias in randomised studies.

Figure 3.

Summary of risk of bias in non-randomised studies.

Figure 4.

Graph summarising risk of bias across randomised studies.

Figure 5.

Graph Summarising the Risk of Bias Across Non-Randomised studies.

Of the ten non-randomised studies, three were rated with low risks of bias, five with moderate risks of bias, and two had a serious risk of bias (see Figure 3). studies by Anthony and McLean (2015) and Burn et al. (2019) were all rated with a "serious" overall risk of bias. In Anthony and McLean's study, the provided intervention was interfered with a second program whose effect highly impacted its results. In the study by Burn et al. participants were involved in setting the goals of the intervention. Overall, most non-randomised studies were rated with a "moderate" risk of bias due to the fears that participants were aware of the intervention received.

3.3. Across studies

Randomised trials had a moderate percentage (15–30%) of high risk of bias in selecting participants, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcomes, missing data, and reporting the outcomes. Most non-randomised studies had a low risk of bias in selecting participants, confounding variables, incomplete data, and maintaining and not deviating from the intended intervention. Most were also rated with critical or serious risk of bias in the measurement of outcome, selection of participants, and classification of intervention domains. Overall, non-randomised studies had a mostly moderate risk of bias (nearly 50%), some had low risk (30%), and some critical and serious risks of bias (20%).

4. Results of individual studies

A tabulated outcomes summary for 36 studies is presented in Appendix B. A few studies (n = 7) were excluded because rather than looking into the effect or outcome of the program, they looked into the reaction of participants being selected (Sorhaindo et al., 2016) or described the service provided (Bigson et al., 2020; de Vries et al., 2016). Other studies focused on personnel providing the service (Raible et al., 2017), explored the problems facing adolescents (Høie et al., 2017), or uncovered barriers that prevented the initiation of a program designed for tween children (Marttinen et al., 2020).

Two studies reported no effect on the program's recipients, and among programs that had a positive impact, very few studies reported effect sizes. The acceptability of provided programs among recipients varied widely from negative to positive and mixed reactions. Fourteen out of fifteen studies reported a positive change in adolescents' attitudes post-intervention. At the post-intervention assessment period, researchers in four studies reported no change in behavioural control among targeted tween children.

Resiliency and copying behaviours of participants in six studies were improved, emotional regulation positively boosted in eight programs, and a reduction in anxiety among participants was reported in seven studies. Few studies reported a change in depression, and among the four studies that reported on internalising problems, Roberts et al. (2018) reported the intervention offered no effect at follow-up. Lastly, researchers who reported on self-esteem and improved wellbeing found that programs positively impacted targeted pre-adolescents.

5. Discussion

Overall, services provided to tween children (see Appendix C) do not appear to address the complexity of circumstances for this age group of children to develop and thrive. If society is to effectively meet the needs of tween children, more attention needs to be given to them, similar to the early childhood period.

5.1. Academic-based programs

The programs provided in school settings included a health education program (hearing loss prevention program (HLP program), STEM outreach program, the SPARK mentoring program, and an abstinence-based sexual education program (ABSEP). Respectively, these programs sought to address ear ailment, promote health literacy, encourage girls to pursue engineering courses, assist children to succeed in schools, and improve communication between parents and daughters around sexual issues and abstinence. The result of the HLP program included identifying the slapping of children by parents, classmates, and strangers contributed to hearing loss; however, adolescents' awareness and ability to seek medical help favoured ear health. The SPARK program strengthened adolescents' ability to cope with daily stressors and was believed by Green et al. (2021) to promote overall health and wellbeing. Researchers believed the ABSEP program promoted parental ability to communicate to their daughters on topics of sex and promoted girls’ knowledge of abstinence. Group discussions, video presentations, and daughters' ability to openly ask questions and understand parental concerns were key to ABSEP positive results.

Most of the programs used survey questionnaires as outcome measurements, and on average, academic programs resulted in positive results. However, none of the identified academic programs was designed for children pressured to excel in their studies. Consequently, the combined effect of academic pressures originating from parents and peers in school may function as sources of distress or dropping from schools if children feel that they are not coping with the pressure, and an intervention is not provided.

5.2. Physical programs

Five interventions produced favourable outcomes in addressing the physical aspects of children. They included the weight-loss treatment programs (ROS), the LIKE program, eye care (EC program), a pain management program, a school feeding program, and human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination program.

Several factors, including the role of parents and siblings, were found to play a significant role in losing weight among obese tween children and the success of the LIKE program. Similar results were seen in a ROS program five years after the intervention. As obese children participated in the ROS weight loss program, there was reciprocity in the influences to and from parents at home that led to weight loss. Eg et al. (2017) reported that, while parents prepared healthy food and checked and controlled food intake, children took the responsibility to commit to the program requirements and lose weight.

In addition, obese children who participated in a telehealth program were required to visit dietitians and psychologists and attended teleconsultation sessions over a period of time. Factors such as the availability of vegetables and improved water and sanitation facilities in homes were found to be essential for improved eye care. Health care staff in the HPV vaccination were found to be key in changing the attitude of female parents towards allowing their children to be HPV vaccinated and media among fathers. Additional factors included the family's cultural and religious beliefs and the cost of the HPV vaccine. Researchers in the EC program argued that there is a decline in children's consumption of foods that promote eye health. Closer collaboration between parents and schools should be maintained for effective eye services to children.

5.3. Psychosocial programs

Eight services were identified as addressing the psychosocial problems of tween children. These included dating violence through the Shifting Boundaries prevention program (SBP program), the Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy for Children (MBCT-C) living with a divorced parent, therapy for sexually abused (TSA), and therapy for war traumatised children. Other psychologically designed programs included the Bounce Back program (BB Program) for fostering resiliency, the FRIENDS For Life Program, a school-based anxiety program (SBA Program), an anti-bullying intervention program (AIP), and the Free to Be program; a mindfulness-based eating disorder prevention program for preteens. Most of these programs used self-reported surveys or inventory as outcome measurement units, and except the FRIENDS For Life Program, which had a mixture of positive and negative outcomes in two different studies, all other services had positive results reported at the end of the follow-up period.

In providing services to victims of sexual abuse, Jessiman et al. (2017) noted factors such as the victim's recovery, therapeutic support, giving children control and power to choose, and the intervention structure to be key for the success of the TSA program. Likewise, Diab et al. (2015) highlighted "family relations" as a significant factor in providing therapy to children traumatised by war. Similarly, Klassen (2017) on the Free to Be program highlighted the media as a significant contributing factor in successfully addressing eating disorders among preteens, showing how factors outside the child have significant impacts on them. The result of the SBA program conflicted with those of the BB program despite all of them targeting to reduce anxiety in children. Researchers identified a reporting bias in the administered questionnaires.

Other successful psychosocial interventions included the Interpersonal Psychotherapy-Adolescent Skills Training (IPT-AST), the ‘Learn Young, Learn Fair’ program, and interventions addressing traumatic grief in adolescents. However, none of the provided psychological interventions was designed to address problems facing children with uncontrollable behaviours and disrupted emotions originating from the loss of employment of a developing child's parent, family tensions and violence, and family breakdown.

With the continuing spike in male-perpetrated domestic violence (Arenas-Arroyo et al., 2021; Parkinson, 2019; Tur-Prats, 2021), it was expected that there would be programs designed for pre-adolescents affected by domestic violence or family breakdown among the studies. The Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy for Children (MBCT-C); an intervention for children living with divorced parents, addressed issues arising from family breakdowns, but no intervention addressed adolescents' problems resulting from domestic violence.

5.4. Intervention with the family

Four services were categorised as being provided to tween children with their families. These included the Family Preservation Services (FPS), Strengthening Family's Program (SFP), Contact Family/Person Program (CFPP), and the Turning into Teens (TINT) program. Except the TINT and SFP programs (Burn et al., 2019), the results of parental and youth reports indicated negative outcomes in a majority of the offered interventions.

SFP showed promising results in reducing pre-adolescent difficulties and parental distress (Burn et al., 2019) but not in addressing adolescent substance misuse (Foxcroft et al., 2017). Despite the worse outcome of reunified children, positive adult-child ties were highlighted by Biehal et al. (2015) as a key contributing factor for the overall success of the FPS. A strong adult-child tie or relationship was also noted by Havighurst et al. (2015) as key to the success of the TINT program. Surveys and reports were used to assess the effectiveness of the program evaluated by Selwyn et al. (2017) on the views of children in foster care about how they are looked after. Concerns were raised by children over the age of 11, including "stigma", a problem which children argued could be overcomed through established trusting relationships with social workers and foster carers.

5.5. Life skills programs

The Aussie Optimism Program (AOP) and IPSY (Information + Psychosocial Competence = Protection) life skills programs were identified as services enabling pre-adolescents to develop their life skills competencies. Despite the study by Kennedy et al. (2015) finding AOP to be non-effective in addressing anxiety and depressive feeling in young adolescents, AOP did increase children's pro-social behaviour and emotional regulation, positively impacted young adolescents' self-esteem and was at least associated with a change in the level of anxiety and depression (Roberts et al., 2018). Likewise, IPSY was effective in addressing young adolescent substance abuse problems (Weichold et al., 2016).

5.6. Paediatric care for transgender children

Two studies described the availability and effectiveness of paediatric care for transgender children and noted a way forward to facilitate children transitioning into adult care. To do this, Shumer et al. (2016) argued for the need to provide further training to caring professionals, and de Vries et al. (2016) argued for the need to have multidisciplinary teams to address the problems they can experience.

5.7. Prevention programs

Overall, positive outcomes were seen in the delivery of the Tobacco prevention program, the BEST teen multi-addiction prevention program, HIV prevention program, teenage pregnancy prevention program, and adolescent relationship abuse (ARA) prevention program. In schools, the establishment of regulatory norms and non-smoking role model teachers were also found to be significant factors that contributed to the deterrence of tobacco use among pre-adolescents (Kim et al., 2020).

5.8. After-school programs

After-school programs included the Opera chorus program, the Reflective Educational Approach to Character and Health (REACH) program, Children's organised out-of-school leisure activities, the Sugar-sweetened beverage intervention (Kids SIPsmartER) program, and the Positive youth development programs. Except for the REACH program, all positively impacted the lives of participating tween children.

In summary, few factors moderated the effectiveness or ineffectiveness of provided services. For instance, while the Tobacco Prevention Program was moderated by gender (Kim et al., 2020), organised sport and art school clubs were moderated by gender, age, and country of origin (Badura et al., 2021). The Health Education Program's effectiveness also depended on the social-economic status of the adolescent's family (Gupta et al., 2015). Another factor that moderated the effectiveness of programs was whether providers considered including carers or parents in pre-adolescents designed interventions (Burn et al., 2019; Eg et al., 2017; Havighurst et al., 2015; Jessiman et al., 2017). Lastly, except for the role of carers and social workers in foster care services, other factors that did not seem to influence the effectiveness of provided services included but were not limited to study design, follow-up period, sample size, and personnel delivering the service.

5.9. Strengths and limitations

Contrary to previously undertaken reviews, this review extensively looked into the diversity of services offered worldwide. However, as a result of the global outlook, the extent to which the result of this study may be transferrable across different cultural settings and contexts may be subject to context and policies in countries of delivery.

It is also interesting to note that most services were offered in the United States, United Kingdom, and Australia, but differences in their politics and policies will also likely underpin what and how much they deliver. Indeed, no single country delivered all of the identified services. Thus, it is beyond the scope of this review to further examine the relationship between policy development and program implementation.

One major limitation of this study was mixing qualitative and quantitative studies and the inability to carry out a meta-analysis. It is also important to acknowledge that limiting this review to English published studies has risked excluding literature on services offered to children in countries where English is not an academic or spoken language.

Another limitation was the generally poor description of study samples. For example, several studies did not fully categorise the age of the children receiving the service (Bigson et al., 2020; Burn et al., 2019; Fleischman et al., 2016; Foxcroft et al., 2017; Hobday et al., 2015; Kennedy et al., 2015; Kösters et al., 2017; Selwyn et al., 2017), and several others provided the school grades of children receiving the intervention instead of their age (Kim et al., 2020; Lehto and Eskelinen, 2020; Raible et al., 2017; Taylor et al., 2017). As a result, it was difficult to ascertain the proportion of children that fell between the ages 10 to 13 out of the total number of children to whom services were provided.

6. Conclusion

This review identified fourteen other systematic reviews of interventions targeting tween children published from the years 2015–2019. The evidence reported in identified reviews was similar to this study, only with minor differences. Similarities were identified in the reporting of resiliency programs and programs addressing substance use in pre-adolescents. First, contradictory reporting on the effectiveness of resiliency programs were highlighted in the review by Bastounis et al. (2016) And Fenwick-Smith et al. (2018). In comparison, similar results were highlighted in this study with positive results reported by Roberts et al. (2018) and Diab et al. (2015) and negative results reported by Kennedy et al. (2015) on the effectiveness of provided resiliency programs. A second similarity was seen in the reporting of interventions addressing the use of substance abuse in adolescent years. As reported in the review undertaken by Hodder et al. (2017), positive outcomes were reported in interventions addressing the use of illicit substance use among adolescents (Kim et al., 2020; Shek et al., 2016). Thirdly, similar to what Johnstone et al. (2018) reported in their review, Burke et al. (2017) explained how ineffective were programs designed to reduce anxiety in children. However, this finding was contradicted by Ab Ghaffar et al. (2019) study, in which a school-based anxiety program effectively reduced anxiety in participating children.

Another difference existing between past reviews and this study is the review method. While the majority of past reviews included a meta-analysis of the results, a meta-analysis of included studies was not possible in this study due to having a variety of programs which, if combined, would have obscured the differences in effects of the programs offered. The last difference is in the number of identified available services. This study identified a multiplicity of services offered to tween children than previous reviews. Additional services identified from past reviews included the Interpersonal Psychotherapy - Adolescent Skills Training (IPT-AST) and The ‘Learn Young, Learn Fair’ program (Woods and Pooley, 2015), additional interventions addressing traumatic grief in adolescents (Greatrex-White and Taggart, 2015), a Virtual Speech-Language Therapy (Lee, 2019), Math Interventions for Students With Autism Spectrum Disorder (King et al., 2016), and the ultrasound visual biofeedback intervention (Sugden et al., 2019), to name but a few.

6.1. Implication for practice

-

•

Practitioners and policymakers should give tween children equal attention to infants and toddlers. This is because the "tween years" is a critical period, as it is early childhood, and if no adequate intervention is not provided, then problems experienced in tween years will be hard to address as children transition into adulthood.

-

•

Coordination and collaboration between organisations should be key factors in addressing pre-adolescent problems. As a matter of fact, the result of this study indicated that most services offered to tween children were independent of each other. That is, service coordination should go beyond providing intervention from multidisciplinary teams to between organisations.

-

•

Given that after-school activities are overlooked, practitioners should pay after-hour or summer camps programs and other related activities as they give participants more opportunities to explore and positively contribute towards their wellbeing.

-

•

The timeframe for the majority of programs identified in this review was limited. Personnel designing and delivering services to tween children should consider designing long-term interventions that provide services to children throughout the tween period for better outcomes.

-

•

No intervention was identified that addresses tween children's sense of inferiority that may result from a lack of self-efficacy in terms of academic achievements and its impact on school dropout and social interaction. This issue is seen to be on par with the need to address problems that may arise from cognitive impairments or hormonal imbalances among tween children.

-

•

Service designers should also consider developing academic programs for children experiencing academic pressures.

-

•

Service providers and policymakers should also consider contextual factors before designing or implementing services to ensure they are appropriate to their context; not all principles are necessarily transferable.

6.2. Implications for future research

Future research should look at studies on services designed for tween children but written in other languages. Replicating by expanding the methodology of this study and including grey literature can also help ensure that the identification of findings is more robust. It would also be ideal to examine the relationship between political aspects that inform policy development and service design and implementation in as many countries as possible.

Services are provided by a wide range of personnel at the community/ground level, but macro-level policies and theories inform their work about what best supports tween children aged 10–13 years. To this end, a robust body of work needs to be developed to support these important members of our society.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Asukulu Solomon Bulimwengu & Jennifer Cartmel: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

No data was used for the research described in the article.

Declaration of interests statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

References

- Ab Ghaffar S.F., Mohd Sidik S., Ibrahim N., Awang H., Gyanchand Rampal L.R. Effect of a school-based anxiety prevention program among primary school children. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2019;16(24):4913. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16244913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthony H., McLean L.A. Promoting mental health at school: short-term effectiveness of a popular school-based resiliency programme. Adv. School Mental Health Prom. 2015;8(4):199–215. [Google Scholar]

- Arenas-Arroyo E., Fernandez-Kranz D., Nollenberger N. Intimate partner violence under forced cohabitation and economic stress: evidence from the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Publ. Econ. 2021;194:104350. doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayers D.N., Harry . Taylor & Francis; 2012. Adolescent Problems. [Google Scholar]

- Badura P., Hamrik Z., Dierckens M., Gobina I., Malinowska-Cieslik M., Furstova J., Kopcakova J., Pickett W. After the bell: adolescents' organised leisure-time activities and wellbeing in the context of social and socioeconomic inequalities. J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 2021 doi: 10.1136/jech-2020-215319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastounis A., Callaghan P., Banerjee A., Michail M. The effectiveness of the Penn Resiliency Programme (PRP) and its adapted versions in reducing depression and anxiety and improving explanatory style: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Adolesc. 2016;52:37–48. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biehal N., Sinclair I., Wade J. Reunifying abused or neglected children: decision-making and outcomes. Child Abuse Negl. 2015;49:107–118. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigson K., Essuman E.K., Lotse C.W. Food hygiene practices at the Ghana school feeding programme in wa and cape coast cities. J. Environ. Public Health. 2020;2020:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2020/9083716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke M.-K., Prendeville P., Veale A. An evaluation of the "FRIENDS for Life" programme among children presenting with autism spectrum disorder. Educ. Psychol. Pract. 2017;33(4):435–449. [Google Scholar]

- Burn M., Lewis A., McDonald L., Toumbourou J.W. An Australian adaptation of the Strengthening Families Program: parent and child mental health outcomes from a pilot study. Aust. Psychol. 2019;54(4):261–271. [Google Scholar]

- Clark A.F., Wilk P., Gilliland J.A. Comparing physical activity behavior of children during school between balanced and traditional school day schedules. J. Sch. Health. 2019;89(2):129–135. doi: 10.1111/josh.12722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vries A.L.C., Klink D., Cohen-Kettenis P.T. What the primary care pediatrician needs to know about gender incongruence and gender dysphoria in children and adolescents. Pediatr. Clin. 2016;63(6):1121–1135. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2016.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derevensky J.L. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers; 2012. Teen Gambling: Understanding a Growing Epidemic. [Google Scholar]

- Diab M., Peltonen K., Qouta S.R., Palosaari E., Punamäki R.-L. Effectiveness of psychosocial intervention enhancing resilience among war-affected children and the moderating role of family factors. Child Abuse Negl. 2015;40:24–35. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan J.E., Molina B.S.G. Antecedent predictors of children's initiation of sipping/tasting alcohol. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 2014;38(9):2488–2495. doi: 10.1111/acer.12517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eg M., Frederiksen K., Vamosi M., Lorentzen V. How family interactions about lifestyle changes affect adolescents' possibilities for maintaining weight loss after a weight-loss intervention: a longitudinal qualitative interview study. J. Adv. Nurs. 2017;73(8):1924–1936. doi: 10.1111/jan.13269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenwick-Smith A., Dahlberg E.E., Thompson S.C. Systematic review of resilience-enhancing, universal, primary school-based mental health promotion programs. BMC Psychol. 2018;6(1) doi: 10.1186/s40359-018-0242-3. 30-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleischman A., Hourigan S.E., Lyon H.N., Landry M.G., Reynolds J., Steltz S.K., Robinson L., Keating S., Feldman H.A., Antonelli R.C., Ludwig D.S., Ebbeling C.B. Creating an integrated care model for childhood obesity: a randomised pilot study utilising telehealth in a community primary care setting: creating an integrated care model using telehealth. Clin. Obes. 2016;6(6):380–388. doi: 10.1111/cob.12166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foxcroft D.R., Callen H., Davies E.L., Okulicz-Kozaryn K. Effectiveness of the strengthening families programme 10-14 in Poland: cluster randomised controlled trial. Eur. J. Publ. Health. 2017;27(3):494–500. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckw195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fradkin C., Valentini N.C., Nobre G.C., dos Santos J.O.L. Obesity and overweight Among Brazilian early adolescents: variability across region, socioeconomic status, and gender. Front. Pediatr. 2018;6:81. doi: 10.3389/fped.2018.00081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallimberti L., Buja A., Chindamo S., Lion C., Terraneo A., Marini E., Gomez Perez L.J., Baldo V. Prevalence of substance use and abuse in late childhood and early adolescence: what are the implications? Prevent. Med. Rep. 2015;2(C):862–867. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2015.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greatrex-White S., Taggart H. Traumatic grief in young people in Sub-Saharan Africa: a scoping review. Nurs. Res. Rev. 2015;5(default):77–89. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta D., Gulati A., Gupta U. Impact of socio-economic status on ear health and behaviour in children: a cross-sectional study in the capital of India. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2015;79(11):1842–1850. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2015.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyer A.E., Silk J.S., Nelson E.E. The neurobiology of the emotional adolescent: from the inside out. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2016;70:74–85. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.07.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen S.G., Frantz R.J., Machalicek W., Raulston T.J. Advanced social communication skills for young children with autism: a systematic review of single-case intervention studies. Rev. J. Autism Develop. Disorder. 2017;4(3):225–242. [Google Scholar]

- Havighurst S.S., Kehoe C.E., Harley A.E. Tuning in to teens : improving parental responses to anger and reducing youth externalising behavior problems. J. Adolesc. 2015;42:148–158. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobday K., Ramke J., du Toit R., Pereira S.M. Healthy Eyes in Schools: an evaluation of a school and community-based intervention to promote eye health in rural Timor-Leste. Health Educ. J. 2015;74(4):392–402. [Google Scholar]

- Hodder R.K., Freund M., Wolfenden L., Bowman J., Nepal S., Dray J., Kingsland M., Yoong S.L., Wiggers J. Systematic review of universal school-based ‘resilience’ interventions targeting adolescent tobacco, alcohol or illicit substance use: a meta-analysis. Prev. Med. 2017;100:248–268. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Høie M., Haraldstad K., Rohde G., Fegran L., Westergren T., Helseth S., Slettebø Å., Johannessen B. How school nurses experience and understand everyday pain among adolescents. BMC Nurs. 2017;16(1):53–58. doi: 10.1186/s12912-017-0247-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessiman P., Hackett S., Carpenter J. Children's and carers' perspectives of a therapeutic intervention for children affected by sexual abuse. Child Fam. Soc. Work. 2017;22(2):1024–1033. [Google Scholar]

- Johnstone K.M., Kemps E., Chen J. A meta-analysis of universal school-based prevention programs for anxiety and depression in children. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2018;21(4):466–481. doi: 10.1007/s10567-018-0266-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy P., Rooney R.M., Kane R.T., Hassan S., Nesa M. The enhanced Aussie Optimism Positive Thinking Skills Program: the relationship between internalising symptoms and family functioning in children aged 9-11 years old. Front. Psychol. 2015;6:504. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S.Y., Jang M., Yoo S., JeKarl J., Chung J.Y., Cho S.-I. School-based tobacco control and smoking in adolescents: evidence from multilevel analyses. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2020;17(10):3422. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17103422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King S.A., Lemons C.J., Davidson K.A. Vol. 82. 2016. Math Interventions for Students with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Best-Evidence Synthesis; pp. 443–462. (Generic) [Google Scholar]

- Klassen S. Free to Be: developing a mindfulness-based eating disorder prevention program for preteens. J. Child Adolesc. Counsel. 2017;3(2):75–87. [Google Scholar]

- Kösters M.P., Chinapaw M.J.M., Zwaanswijk M., van der Wal M.F., Utens E.M.W.J., Koot H.M. FRIENDS for Life: implementation of an indicated prevention program targeting childhood anxiety and depression in a naturalistic setting. Mental Health Prevent. 2017;6:44–50. [Google Scholar]

- Lee S.A.S. Virtual Speech-Language therapy for individuals with communication disorders: current evidence, limitations, and benefits. Curr. Develop. Disorder. Rep. 2019;6(3):119–125. [Google Scholar]

- Lehto S., Eskelinen K. ‘Playing makes it fun’ in out-of-school activities: children’s organised leisure. Childhood. 2020;27(4):545–561. [Google Scholar]

- Lui J.H.L., Lui J.H.L., Barry C.T., Barry C.T., Sergiou C.S., Sergiou C.S. Interventions for improving affective abilities in adolescents: an integrative review across community and clinical samples of adolescents. Adolesc. Res. Rev. 2017;2(3):229–249. [Google Scholar]

- Marttinen R., Fredrick R.N., Johnston K., Phillips S., Patterson D. Implementing the REACH after-school programme for youth in urban communities: challenges and lessons learned. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2020;26(2):410–428. [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane K. Care-criminalisation: the involvement of children in out-of-home care in the New South Wales criminal justice system. Aust. N. Z. J. Criminol. 2018;51(3):412–433. [Google Scholar]

- McGuinness L.A., Higgins J.P.T. Risk-of-bias VISualization (robvis): an R package and Shiny web app for visualising risk-of-bias assessments. Res. Synth. Methods. 2021;12(1):55–61. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesa-Gresa P., Gil-Gómez H., Lozano-Quilis J.-A., Gil-Gómez J.-A. Effectiveness of virtual reality for children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: an evidence-based systematic review. Sensors. 2018;18(8):2486. doi: 10.3390/s18082486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milevsky A. Springer Publishing Company; 2015. Understanding Adolescents for Helping Professionals. [Google Scholar]

- Nader K. Taylor & Francis; 2019. Handbook of Trauma, Traumatic Loss, and Adversity in Children: Development, Adversity’s Impacts, and Methods of Intervention. [Google Scholar]

- Noel J.K. Associations between alcohol policies and adolescent alcohol use: a pooled analysis of GSHS and ESPAD. Data. Alcohol Alcohol. 2019;54(6):639–646. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agz068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olvera N., McCarley K., Rodriguez A.X., Noor N., Hernández-Valero M.A. Body image disturbances and predictors of body dissatisfaction among hispanic and white pre-adolescents. J. Res. Adolesc. 2015;25(4):728–738. [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson D. Investigating the increase in domestic violence post disaster: an Australian case study. J. Interpers Violence. 2019;34(11):2333–2362. doi: 10.1177/0886260517696876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poddar P. Parents expectations and academic pressure: a major cause of stress among students. J. Electron. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- Raible C.A., Dick R., Gilkerson F., Mattern C.S., James L., Miller E. School nurse-delivered adolescent relationship abuse prevention. J. Sch. Health. 2017;87(7):524–530. doi: 10.1111/josh.12520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redmond G., Skattebol J., Saunders P., Lietz P., Zizzo G., O'Grady E., Tobin M., Maurici V., Huynh J., Moffat A. 2016. Are the Kids Alright? Young Australians in Their Middle Years: Final Summary Report of the Australian Child Wellbeing Project. [Google Scholar]

- Review Manager (RevMan) The Cochrane Collaboration; 2020. [computer Program] Version 5.4. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts C.M., Kane R.T., Rooney R.M., Pintabona Y., Baughman N., Hassan S., Cross D., Zubrick S.R., Silburn S.R. Efficacy of the Aussie optimism program: promoting pro-social behavior and preventing suicidality in primary school students. A randomised-controlled trial. Front. Psychol. 2018;8:1392. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossow I., Kuntsche E.N. Early onset of drinking and risk of heavy drinking in young adulthood: a 13-year prospective study. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 2013;37(1):E297–E304. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01924.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selwyn J., Wood M., Newman T. Looked after children and young people in england: developing measures of subjective well-being. Child Indicat. Res. 2017;10(2):363–380. [Google Scholar]

- Shek D.T.L., Yu L., Leung H., Wu F.K.Y., Law M.Y.M. Development, implementation, and evaluation of a multi-addiction prevention program for primary school students in Hong Kong: the BEST Teen Program. Asian J. Gambl. Issues Public Health. 2016;6(1):1–17. doi: 10.1186/s40405-016-0014-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shumer D.E., Nokoff N.J., Spack N.P. Advances in the care of transgender children and adolescents. Adv. Pediatr. 2016;63(1):79–102. doi: 10.1016/j.yapd.2016.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith P.K. Bullying: definition, types, causes, consequences and intervention: bullying. Social Personal. Psychol. Compass. 2016;10(9):519–532. [Google Scholar]

- Sorhaindo A., Bonell C., Fletcher A., Jessiman P., Keogh P., Mitchell K. Being targeted: young women's experience of being identified for a teenage pregnancy prevention programme. J. Adolesc. 2016;49:181–190. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L.D. eleventh ed. McGraw-Hill Education; 2017. Adolescence. [Google Scholar]

- Sterne J.A.C., Hernán M.A., Reeves B.C., Savović J., Berkman N.D., Viswanathan M., Henry D., Altman D.G., Ansari M.T., Boutron I., Carpenter J.R., Chan A.-W., Churchill R., Deeks J.J., Hróbjartsson A., Kirkham J., Jüni P., Loke Y.K., Pigott T.D., Ramsay C.R., Regidor D., Rothstein H.R., Sandhu L., Santaguida P.L., Schünemann H.J., Shea B., Shrier I., Tugwell P., Turner L., Valentine J.C., Waddington H., Waters E., Wells G.A., Whiting P.F., Higgins J.P.T. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016;355:i4919. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugden E., Lloyd S., Lam J., Cleland J. Systematic review of ultrasound visual biofeedback in intervention for speech sound disorders. Int. J. Lang. Commun. Disord. 2019;54(5):705–728. doi: 10.1111/1460-6984.12478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor B.G., Taylor B.G., Mumford E.A., Mumford E.A., Liu W., Liu W., Stein N.D., Stein N.D. The effects of different saturation levels of the Shifting Boundaries intervention on preventing adolescent relationship abuse and sexual harassment. J. Exp. Criminol. 2017;13(1):79–100. [Google Scholar]

- Tur-Prats A. Unemployment and intimate partner violence: a Cultural approach. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2021;185:27–49. [Google Scholar]

- Webb H.J., Zimmer-gembeck M.J., Mastro S., Farrell L.J., Waters A.M., Lavell C.H. Young adolescents' body dysmorphic symptoms: associations with same- and cross-sex peer teasing via appearance-based rejection sensitivity. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2015;43(6):1161–1173. doi: 10.1007/s10802-014-9971-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weichold K., Tomasik M.J., Silbereisen R.K., Spaeth M. The effectiveness of the life skills program IPSY for the prevention of adolescent tobacco use: the mediating role of yielding to peer pressure. J. Early Adolesc. 2016;36(7):881–908. [Google Scholar]

- Woods R., Pooley J.A. A review of intervention programs that assist the transition for adolescence into high school and the prevention of mental health problems. Int. J. Child Adolesc. Health. 2015;8(2):97. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No data was used for the research described in the article.