ABSTRACT

Background

Apathy and depression commonly occur in patients with progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP)‐Richardson's syndrome variant; depression often requiring treatment. Little is known, however, about apathy and depression among other PSP variants.

Methods

We prospectively studied 97 newly diagnosed PSP patients. All were classified into a PSP variant using the 2017 Movement Disorder Society‐PSP criteria and administered the Geriatric Depression and Apathy Evaluation Scales. Differences in apathy and depression frequency and severity across six variants, and secondarily across PSP‐Richardson's syndrome, PSP‐Cortical and PSP‐Subcortical, were analyzed using ANCOVA and linear regression adjusting for disease severity.

Results

Depression (55%) was more common than apathy (12%). PSP‐Speech/Language (PSP‐SL) variant had the lowest depression frequency (13%) and lower depression scores than the other variants. No differences in apathy frequency/severity were identified.

Conclusion

PSP‐SL patients may have less depression compared to PSP‐Richardson's syndrome and other PSP variants.

Keywords: PSP, Richardson syndrome, speech apraxia, PSP‐cortical, variants

Progressive Supranuclear Palsy (PSP) is a neurodegenerative disease with a prevalence of about 1/100,000. 1 Diagnosis of PSP is based on common symptoms such as slowness of movement, neck stiffness, loss of balance and early falls with neurological examination findings of vertical supranuclear gaze palsy, axial rigidity, appendicular bradykinesia and postural instability. 2

In 2017, the Movement Disorder Society published new diagnostic criteria for PSP (MDS‐PSP) formally recognizing different PSP variants: Richardson Syndrome (PSP‐RS), Parkinsonism (PSP‐P), Postural Gait freezing (PSP‐PGF), Speech and Language (PSP‐SL), Corticobasal Syndrome (PSP‐CBS), 3 Frontal (PSP‐F), Ocular Motor (PSP‐OM), and Postural instability (PSP‐PI). 4 The new criteria together with instructions on how to apply them 5 differentiated the subtypes based on their predominant symptoms, and categorized diagnoses into probable, possible, and suggestive of PSP. The criteria have been found to have excellent sensitivity and very good specificity for PSP. 6 , 7

Depression and apathy have been well described in PSP, 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 especially PSP‐RS, the most common variant. A recent systematic review found a mean prevalence of 59.7% for depression and 58.3% for apathy in patients with PSP. 13 There has only been one study that compared depression and apathy among MDS‐PSP defined variants. 14 Forty‐nine patients in that study were diagnosed retrospectively using the MDS‐PSP criteria.

Given the knowledge gap regarding apathy and depression across PSP variants, we compared depression and apathy severity and frequency among patients diagnosed prospectively using the MDS‐PSP criteria. We hypothesize that PSP‐SL patients would have higher (worse) depression and apathy scores due to loss of ability to verbally communicate 3 but that no differences would be observed across the other PSP variants. 14

Methods

We studied 97 newly diagnosed patients diagnosed with PSP at Mayo Clinic, MN between 2017 and 2021. All 97 patients were prospectively enrolled into an NIH funded grant and evaluated by one of three board‐certified neurologists specializing in Movement Disorders (KAJ, FA, HB). At the time of study enrollment, we categorized each patient into a PSP variant using the MDS‐PSP and MAX criteria. 4 , 5 We also determined overall severity of disease at the time of presentation using the PSP rating scale. 15 All 97 patients were administered the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) to measure depression severity and the Apathy Evaluation Scale (AES) to measure apathy severity. Anti‐depressant usage before or at the time of enrollment was recorded.

The GDS is a self‐reported measure of depression consisting of 15 questions requiring a yes or no response with a total score of 15. Questions were selected as they correlated with depressive symptoms in a validation study. 16 A score ≥ 5 is suggestive of depression. 16 The GDS has been used in both research and clinical practice to identify depression. The AES is an independent valid and reliable scale used to determine apathy severity. 17 We used the carer/informant version (AES‐I) consisting of 18 items. For each item carers select one of four responses: not at all true; slightly true, somewhat true, and very true. The AES‐I has a score range of 18–72. A score ≥ 36.5 is suggestive of apathy. 17

Given the small number of subjects with PSP‐F, PSP‐PI, and PSP‐OM in our cohort we combined these variants as PSP‐Other. As a secondary analysis we analyzed our patients divided into three groups: PSP‐RS, PSP‐Cortical (PSP‐SL + PSP‐CBS + PSP+ F) and PSP‐Subcortical (PSP‐P + PSP‐PGF + PSP‐OM + PSP‐PI). We compared demographic and clinical data across the six PSP variants with analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables and Fisher's exact test for variables reported as frequencies. To compare depression and apathy severity across PSP variants while accounting for disease severity via the PSP rating scale, we performed analysis of covariance (ANCOVA). The ANCOVA model was specified with PSP variant as a random effect or factor as a way to reduce estimation error via penalization or “shrinkage”. 18 Model estimates and 95% confidence intervals were obtained using the rstanarm package. 19 Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

Demographic and clinical features of all 97 patients by variant are shown in Table 1. The most common diagnosis in our cohort was PSP‐RS (49%), followed by PSP‐P (21%), PSP‐PGF (8%), PSP‐SL (8%), PSP‐CBS (7%) and PSP‐Other (6%). Overall, there were no differences in demographic features across the six different PSP categories (i.e., variants) except for disease duration. There were clinical differences on the Frontal Assessment Battery and Apraxia of Speech Rating Scale. Differences in duration were driven mainly by the PSP‐SL and PSP‐P groups having on average the longest durations of 7.6 and 5.4 years, respectively. The PSP‐SL group also had the highest mean disease severity as measured by the PSP rating scale (42 points) followed once again by PSP‐P (39 points) although we did not observe a difference in PSP severity across groups (P = 0.58). Sixty‐one patients (63%) were on an anti‐depressant at study entry without any difference in frequency across variants. There was a trend for a difference in the GDS total score (P = 0.07) but no difference in the AES total score across the variants. The percentage of patients meeting criteria for depression based on a cut point of ≥5‐points on the GDS was 56% across all 97 patients with differences observed between some groups (Table 1). All 6 PSP‐Other patients (100%) but only one of the eight (13%) PSP‐SL patients met criteria for depression. A diagnosis of apathy based on a cut‐off of ≥36.5 points on the AES was lower in frequency, compared to depression, across all PSP variants (12%), with PSP‐Other having the highest frequency (17%), followed by PSP‐RS (15%) and PSP‐P (15%). There was no difference in frequency of those that met apathy criteria across variants.

TABLE 1.

Demographics and clinical features across six PSP groups

| Variable | PSP‐RS, N = 48 | PSP‐P, N = 20 | PSP‐PGF, N = 8 | PSP‐SL, N = 8 | PSP‐CBS, N = 7 | PSP‐Other, N = 6 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female, n (%) | 22 (46%) | 6 (30%) | 6 (75%) | 4 (50%) | 3 (43%) | 5 (83%) | 0.16 |

| Age at Encounter | 70.3 (65.2, 74.8) | 70.4 (68.0, 74.0) | 74.4 (71.9, 77.6) | 73.9 (70.0, 77.1) | 69.7 (64.2, 71.5) | 68.5 (57.9, 75.6) | 0.10 |

| Age at onset | 65.7 (61.8, 70.0) | 64.8 (58.7, 68.0) | 71.5 (67.7, 76.2) | 67.3 (62.4, 69.3) | 68.0 (62.4, 69.4) | 64.1 (52.2, 72.5) | 0.14 |

| R‐Hand, n (%) | 40 (85%) | 16 (89%) | 5 (71%) | 8 (100%) | 6 (86%) | 5 (83%) | 0.72 |

| Education, y | 16 (14, 16) | 16 (14, 16) | 15 (14, 16) | 16 (15, 18) | 12 (12, 15) | 12 (12, 16) | 0.31 |

| On antidepressant at study entry, n (%)** | 29 (60%) | 12 (60%) | 4 (50%) | 6 (75%) | 5 (71%) | 5 (83%) | 0.82 |

| PSP Rating Scale | 37.5 (30.8, 46.0) | 39.0 (34.5, 42.8) | 32.0 (30.2, 38.8) | 42.0 (37.8, 50.2) | 34.0 (20.5, 51.0) | 28.0 (24.8, 31.2) | 0.58 |

| MoCA | 24 (21, 27) | 26 (23, 27) | 26 (24, 26) | 22 (18, 24) | 21 (17, 24) | 24 (22, 25) | 0.22 |

| FAB | 14 (13, 16) | 14 (13, 16) | 15 (13, 16) | 12 (10, 13) | 12 (8, 14) | 12 (10, 14) | 0.03 |

| Boston naming | 14 (12, 14) | 14 (12, 15) | 12 (12, 13) | 15 (15, 15) | 11 (10, 12) | 13 (12, 14) | 0.10 |

| ASRS | 4 (2, 6) | 4 (2, 6) | 2 (1, 3) | 33 (26, 44) | 3 (2, 5) | 4 (3, 6) | <0.001 |

| Disease Duration at encounter | 3.36 (2.33, 4.33) | 5.40 (4.49, 10.01) | 3.08 (2.37, 3.35) | 7.63 (5.85, 8.95) | 2.34 (1.88, 2.71) | 3.87 (2.30, 6.45) | <0.001* |

| GDS total | 5.5 (3.8, 7.2) | 4.5 (3.0, 6.2) | 6.0 (5.0, 8.2) | 2.5 (1.8, 3.2) | 4.0 (3.0, 5.5) | 7.0 (5.5, 7.0) | 0.07 |

| AES total | 19.0 (10.8, 29.2) | 24.0 (14.5, 32.8) | 12.5 (7.5, 23.0) | 10.0 (7.5, 24.5) | 17.0 (8.0, 24.0) | 18.0 (16.0, 20.0) | 0.44 |

| GDS ≥5 (%) | 28 (58%) | 10 (50%) | 6 (75%) | 1 (12%) | 3 (43%) | 6 (100%) | 0.02* |

| AES ≥36 (%) | 7 (15%) | 3 (15%) | 1 (12%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (17%) | 0.90 |

| Disease duration | GDS total score | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSP‐P | PSP‐PGF | PSP‐SL | PSP‐CBS | PSP‐Other | PSP‐P | PSP‐PGF | PSP‐SL | PSP‐CBS | PSP‐Other | ||

| PSP‐RS | <0.001 | >0.99 | 0.001 | 0.77 | 0.93 | PSP‐RS | 0.60 | 0.46 | 0.02 | 0.69 | 0.07 |

| PSP‐P | NA | 0.04 | 0.94 | 0.002 | 0.58 | PSP‐P | NA | 0.40 | 0.10 | >0.99 | 0.053 |

| PSP‐SL | NA | 0.02 | NA | 0.001 | 0.28 | PSP‐SL | NA | 0.04 | NA | 0.28 | 0.005 |

| PSP‐PGF | NA | NA | NA | 0.98 | 0.91 | PSP‐PGF | NA | NA | NA | 0.31 | 0.47 |

| PSP‐CBS | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.53 | PSP‐CBS | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.07 |

The PSP‐Other group consisted of PSP‐PI, PSP‐OM, and PSP‐F. Data shown as n (%) or median (IQR).

Pairwise P‐values.

Sertraline (23%), citalopram (13%), escitalopram (13%), trazodone (11%), mirtazapine (10%), bupropion (8%), duloxetine (8%), paroxetine (5%), venlafaxine (5%), fluoxetine (3%), desvenlafaxine (2%), antidepressant name unknown (3%). Some patients were on more than one antidepressant.

Abbreviations: AES, Apathy Evaluation Scale; ASRS, Apraxia of Speech Rating Scale; FAB, Frontal Assessment Battery; GDS, Geriatric Depression Scale.

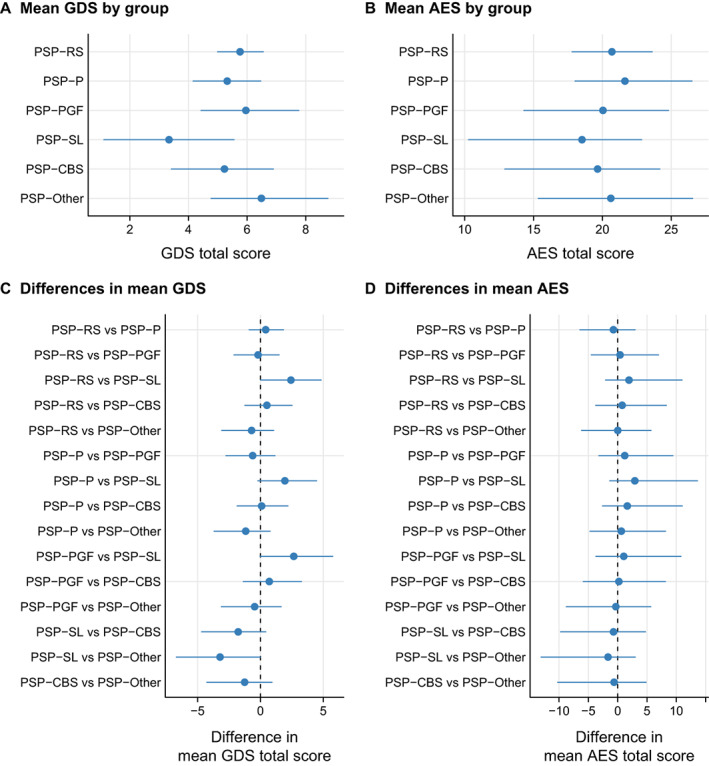

We did not find any relationship between disease duration and GDS or AES score, but higher GDS and AES scores were associated with greater severity (Figure S1). Figure 1 shows the results of the ANCOVA which are based on a model that enables pairwise comparisons without inflating the false positive rate. The PSP‐SL variant had significantly lower GDS scores compared to PSP‐Other, PSP‐PGF and PSP‐RS with a similar trend noted for PSP‐P and for PSP‐CBS. No other differences on the GDS were observed. We did not find any difference in AES score across the PSP variants.

FIG 1.

Estimated mean geriatric depression scale (GDS) (A) and mean apathy evaluation scale (AES) (B) by PSP categorized into PSP‐RS, PSP‐P, PSP‐PGF, PSP‐SL, PSP‐CBS and PSP‐other; estimates were from a linear regression model. Differences between each of two groups compared for GDS (C) and AES severity (D) accounting for disease severity via the PSP rating scale was performed with analysis of covariance (ANCOVA).

We did not find any differences in GDS or AES frequency or severity across PSP‐RS, PSP‐Cortical and PSP‐Subcortical (Table S1 and Figure S2).

Discussion

In this large prospective study on apathy and depression across PSP variants we found little evidence for differences across variants except for PSP‐SL which was less frequent and showed lower scores on the GDS. This finding does not support our initial hypothesis yet is novel, as this study prospectively assessed depression and apathy across six PSP variants including PSP‐SL.

Across the entire cohort we found 56% of our patients met criteria for depression which is similar to the frequency of depression reported in a recent large systematic study 13 and other studies. 8 , 20 , 21 Our frequency was, however, lower than that reported in another study (77%) that assessed depression across PSP variants using the MDS‐PSP criteria. 14 One explanation for the lower frequency in our study could be that our patients were less severe. Our PSP‐RS patients, for example, were on average 10‐points lower on the PSP rating scale. In addition, our study included PSP‐SL patients and PSP‐SL patients were the least depressed and hence would have further lowered the frequency in our cohort. Another explanation for differences could be related to the fact that we used the GDS while in their study depression was measured using the Becks Depression Inventory II.

Sixty‐three percent of the PSP patients in this cohort were on an antidepressant at study enrollment, without any relationship to PSP variant. We also did not find any relationship between frequency of antidepressant use and PSP group when we combined our patients into PSP‐RS, PSP‐cortical and PSP‐subcortical groups suggesting that antidepressant use is independent of anatomical dominance (cortical versus subcortical). It should also be noted that in some instances the use of an antidepressant was driven by off‐label use. For example, Trazadone was sometimes utilized in patients with insomnia, and anxiety was also treated with antidepressants. This would explain why antidepressant usage was more frequent (63%) than the frequency of depression (56%) in our patients. The frequency of depression and antidepressant use in our study was slightly higher than that reported in a recent survey of neurologists who treat PSP variant patients. 21

We did not find apathy to be more frequent in our cohort, or in any one variant, compared to depression as reported 14 and our frequency was lower than what was found in one systematic study (12% vs. 58%). 13 There are, however, similarly reported low frequencies of apathy in the literature. For example, apathy was reported in 21% of PSP‐RS patients in one study. 22 In addition, our average AES score of 19 was almost identical that reported in another study. 23 It is possible that differences across studies are related to differences in disease severity, diagnostic criteria for apathy, different cut‐offs used by for defining presence/absence of apathy, and different study designs such as retrospective versus prospective. It is also possible that carers of PSP patients are underscoring apathy severity on the AES‐I since the AES‐I has not been validated in PSP. With‐that‐said, no study has found a difference in apathy frequency or severity across the different MDS‐PSP defined variants.

In summary, depression and apathy severity differed minimally across PSP variants except for PSP‐SL where depression was less frequent and less severe. The results of this study have important clinical implications. Most patients with PSP‐RS and depression are treated with antidepressants; 63% in this cohort. It appears that there is no difference in threshold for treating depression across PSP variants or across cortical and subcortical variants. Our study shows that those with other variants, including PSP‐SL were equal, or more likely to be on an antidepressant. The findings support the notion that all PSP variants should be screened and considered for treatment of apathy and depression. The strength of our study is the large number of prospectively recruited patients. Limitation of the study were that the GDS and AES have not been validated in PSP and that our PSP‐PI, PSP‐OM and PSP‐F were too small for individual variant comparisons.

Author Roles

(1) Research project: A. Conception, B. Organization, C. Execution; (2) Statistical Analysis: A. Design, B. Execution, C. Review and Critique; (3) Manuscript: A. Writing of the first draft, B. Review and Critique.

S.M.B.: 1A, 1B, 1C, 3A

S.D.W.: 1C, 2A, 2B, 2C, 3B

F.A.: 1C, 3B

H.M.C.: 1C, 3B

H.B.: 1C, 3B

J.A.S.: 1C, 3B

J.L.W.: 1C, 3B

K.A.J.: 1A, 1B, 1C, 3B

Disclosures

Ethical Compliance Statement

The study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board (IRB). All patients consented to participate in the research study via a written signed consent that was completed in the presence of a witness to the signing of the consent. All authors have read and complied with the Journal's Ethical Publication Guidelines. We confirm that we have read the Journal's position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this work is consistent with those guidelines.

Funding Sources and Conflicts of Interest

This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health grants: RF1‐NS112153, R01‐DC12519, R01‐NS89757, R01‐DC010367, R21‐NS94684 and R01‐DC14942. The authors have no conflicts of interest pertaining to this manuscript.

Financial Disclosures for the Previous 12 Months

Ms. Sarah Bower reports no disclosures. Mr. Stephen Weigand reports no disclosures. Dr. Farwa Ali reports no disclosures. Dr. Clark reports no disclosures. Dr. Botha reports no disclosures. Dr. Stierwalt reports no disclosures. Dr. Whitwell received funding from the NIH. Dr. Josephs received funding from the NIH.

Supporting information

Figure S1. Relationship between Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) scores and Apathy Evaluation Scale (AES) scores and disease duration or disese severity via the PSP Rating Scale among all participants. Neither GDS nor AES were found to be related to disease duration (rank correlation [r] = 0.10, p = 0.31 and r = 0.09, p = 0.38, respectively). Higher GDS and AES scores appeared to be associated with higher scores on the PSP Rating Scale (r = 0.18, p = 0.08 and r = 0.29, p = 0.004, respectively.)

Figure S2. Estimated mean Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) and mean Apathy Evaluation Scale (AES) by PSP categorized into PSP‐RS, PSP‐Cortical, and PSP‐Subcortical. Estimates were from a linear regression model. F‐tests indicated no differences by group for GDS (p = 0.19) nor for AES (p = 0.40).

Table S1. Baseline characteristics across PSP‐RS, PSP‐Cortical & PSP‐Subcortical.

References

- 1. Nath U, Ben‐Shlomo Y, Thomson RG, et al. The prevalence of progressive supranuclear palsy (Steele‐Richardson‐Olszewski syndrome) in the UK. Brain 2001;124:1438–1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Litvan I. Diagnosis and management of progressive supranuclear palsy. Semin Neurol 2001;21:41–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Clark HM, Utianski RL, Ali F, Botha H, Whitwell JL, Josephs KA. Motor speech disorders and communication limitations in progressive supranuclear palsy. Am J Speech Lang Pathol 2021;30:1361–1372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hoglinger GU, Respondek G, Stamelou M, et al. Clinical diagnosis of progressive supranuclear palsy: the movement disorder society criteria. Mov Disord 2017;32:853–864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Grimm MJ, Respondek G, Stamelou M, et al., for the Movement Disorder Society‐endorsed PSP Study Group. How to apply the movement disorder society criteria for diagnosis of progressive supranuclear palsy. Mov Disord 2019;34:1228–1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ali F, Martin PR, Botha H, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of diagnostic criteria for progressive Supranuclear palsy. Mov Disord 2019;34:1144–1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Respondek G, Grimm MJ, Piot I, et al. Validation of the movement disorder society criteria for the diagnosis of 4‐repeat tauopathies. Mov Disord 2020;35:171–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Almeida L, Ahmed B, Walz R, et al. Depressive symptoms are frequent in atypical Parkinsonian disorders. Mov Disord Clin Pract 2017;4:191–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Esmonde T, Giles E, Gibson M, Hodges JR. Neuropsychological performance, disease severity, and depression in progressive supranuclear palsy. J Neurol 1996;243:638–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Borroni B, Turla M, Bertasi V, Agosti C, Gilberti N, Padovani A. Cognitive and behavioral assessment in the early stages of neurodegenerative extrapyramidal syndromes. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2008;47:53–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Josephs KA, Whitwell JL, Eggers SD, Senjem ML, Jack CR Jr. Gray matter correlates of behavioral severity in progressive supranuclear palsy. Mov Disord 2011;26:493–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cordato NJ, Halliday GM, Caine D, Morris JG. Comparison of motor, cognitive, and behavioral features in progressive supranuclear palsy and Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 2006;21:632–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Flavell J, Nestor PJ. A systematic review of apathy and depression in progressive Supranuclear palsy. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 2021;089198872199354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Picillo M, Cuoco S, Tepedino MF, et al. Motor, cognitive and behavioral differences in MDS PSP phenotypes. J Neurol 2019;266:1727–1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Golbe LI, Ohman‐Strickland PA. A clinical rating scale for progressive supranuclear palsy. Brain 2007;130:1552–1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sheikh JI, Yesavage JA. Geriatric depression scale (GDS): recent evidence and development of a shorter version. Aging Ment Health 1986;5:165–173. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Marin RS, Biedrzycki RC, Firinciogullari S. Reliability and validity of the apathy evaluation scale. Psychiatry Res 1991;38:143–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Greenland S. Principles of multilevel modelling. Int J Epidemiol 2000;29:158–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Muth C, Oravecz Z, Gabry J. User‐friendly Bayesian regression modeling: a tutorial with rstanarm and shinystan. Quant Meth Psychol 2018;14:99–119. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bloise MC, Berardelli I, Roselli V, et al. Psychiatric disturbances in patients with progressive supranuclear palsy: a case‐control study. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2014;20:965–968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Morgan JC, Ye X, Mellor JA, et al. Disease course and treatment patterns in progressive supranuclear palsy: a real‐world study. J Neurol Sci 2021;421:117293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pellicano C, Assogna F, Cellupica N, et al. Neuropsychiatric and cognitive profile of early Richardson's syndrome, progressive supranuclear palsy‐parkinsonism and Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2017;45:50–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Agosta F, Galantucci S, Svetel M, et al. Clinical, cognitive, and behavioural correlates of white matter damage in progressive supranuclear palsy. J Neurol 2014;261:913–924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Relationship between Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) scores and Apathy Evaluation Scale (AES) scores and disease duration or disese severity via the PSP Rating Scale among all participants. Neither GDS nor AES were found to be related to disease duration (rank correlation [r] = 0.10, p = 0.31 and r = 0.09, p = 0.38, respectively). Higher GDS and AES scores appeared to be associated with higher scores on the PSP Rating Scale (r = 0.18, p = 0.08 and r = 0.29, p = 0.004, respectively.)

Figure S2. Estimated mean Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) and mean Apathy Evaluation Scale (AES) by PSP categorized into PSP‐RS, PSP‐Cortical, and PSP‐Subcortical. Estimates were from a linear regression model. F‐tests indicated no differences by group for GDS (p = 0.19) nor for AES (p = 0.40).

Table S1. Baseline characteristics across PSP‐RS, PSP‐Cortical & PSP‐Subcortical.