Abstract

Antitumor immunosurveillance is triggered by immune cell recognition of characteristic biochemical signals on the surfaces of cancer cells. Recent data suggest that the mechanical properties of cancer cells influence the strength of these signals, with physically “harder” target cells (more rigid) eliciting “better, faster, and stronger” cytotoxic responses against metastasis. Using analogies to a certain electronic music duo, we argue that the biophysical properties of cancer cells and their environment can adjust the volume and tone of the antitumor immune response. We also consider the potential influence of biomechanics-based immunosurveillance in disease progression and posit that targeting the biophysical properties of cancer cells in concert with their biochemical features could increase the efficacy of immunotherapy.

Antitumor immunosurveillance: the concert stage

The immune system has evolved to protect organisms from external threats such as bacteria and viruses as well as internal threats such as transformation and aging-associated dysfunction. To carry out their protective functions, immune cells recognize activating ligands displayed on other immune cells or on infected, damaged, or transformed target cells and then form stereotypic intercellular contacts, called immunological synapses. It is through these synapses that pathogen-neutralizing effector responses such as phagocytosis and host cell killing are accomplished [1–3]. The complex biochemical orchestrations driving these processes are well studied, and over the past two decades, therapeutic targeting of relevant signaling cascades (e.g. immune checkpoint blockade [ICB]) has led to the development of new and in some cases, efficacious clinical strategies in immuno-oncology [4].

Immunological synapses also exhibit essential biophysical features and architecture requirements that have more recently come to light (reviewed in [5]). Whether and how therapeutic modulation of these properties via biomechanical interventions might eventually contribute to the treatment of infections, cancer, aging disorders, or other ailments, remains unknown. Herein, we argue that a recently identified mechanical form of antitumor immunosurveillance potentially represents a new opportunity for combating cancer and other diseases. We place this discovery in the context of both mechanobiology and basic immunology, discussing the technical limitations and latest advances in these fields of study, as well as offering prospective directions and translational applications.

Biophysics and biochemistry collaborate to make immunological music

The common representation of immune cells as featureless dots on flow cytometry or t-SNE plots belies their remarkable structural plasticity and capacity for movement. Our growing understanding of the mechanical lifestyles of immune cells owes a great deal to observations made possible by high-resolution imaging and biophysical tools such as atomic force microscopy (AFM) and force clamp technology – now accessible methods that were typically found only in engineering departments 10 years ago. Recent work has made clear that immune cells utilize their dynamic cellular architectures, powered by the cytoskeleton, (i) to exert mechanical forces outwardly (against the extracellular environment or the surfaces of other cells) and (ii) to sense and respond to the mechanical properties of the environment (such as tissue rigidity, reviewed in [5]). Despite this progress, our understanding of the specific mechanisms by which cellular biomechanics contributes to immune function remains limited. This is due in large part to the difficulty of delineating biophysical from biochemical effects. Leukocyte activation is not a solo performance, but rather, a combination of biochemical and biophysical processes that must act in concert to deliver a successful mesoscale response. This simultaneous coordination and indiscernibility of biochemical and biophysical activities in immune cells is reminiscent of the French electronic duo Daft Punki, who covered their faces with helmets during their performances (see Resources): individually, each member’s contributions to the music were difficult to identify; there can be no argument, however, that both were essential for success (Figure 1).

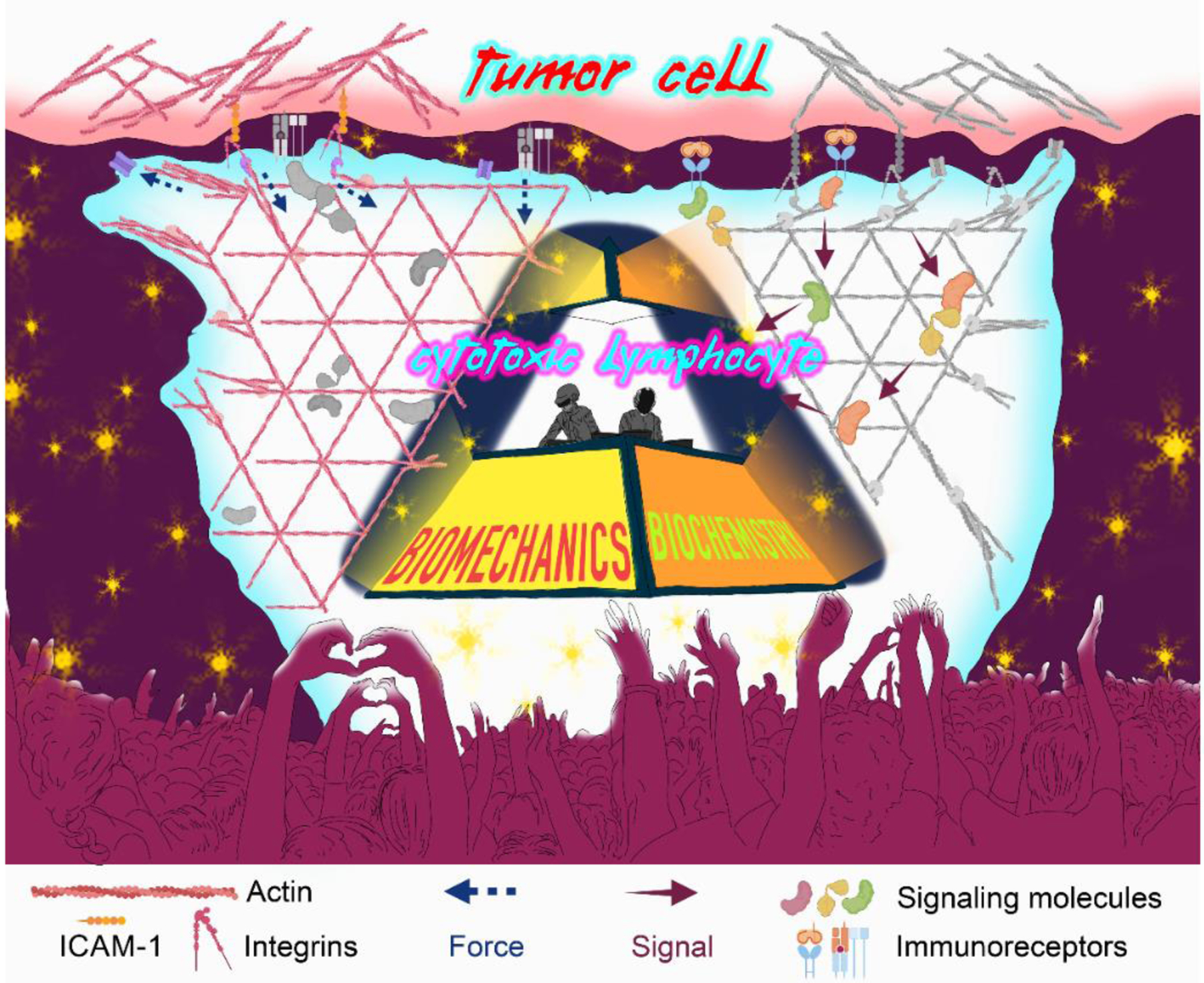

Figure 1. Biophysics and biochemistry collaborate to make immunological music.

Cytotoxic lymphocyte activation by a tumor cell is schematized using the iconic Daft Punk pyramid. Biomechanical inputs, and force exertion though the filamentous actin cytoskeleton and cell surface integrins, are highlighted on the left, while key biochemical signaling pathways are highlighted on the right. Both components work in concert to elicit strong cytotoxic and inflammatory responses.

Physicochemical synergy in the immune system is perhaps best understood in the case of immunoreceptor signaling. The receptors responsible for immune cell activation not only bind to specific biochemical ligands, but also respond to mechanical forces by forming catch bonds, which are non-covalent interactions that increase in affinity under mechanical tension (reviewed in [6]). Integrins (e.g. LFA-1) are the archetypal catch bond receptors, transforming pulling forces powered by the actomyosin cytoskeletal network into conformational changes that promote, rather than destabilize, ligand binding on the interacting cell surface [7–9]. Additional force-dependent conformational changes also drive signal transduction by inducing the assembly of outside-in complexes about the integrin cytoplasmic tails [10, 11]. Hence, while biochemical signals “turn on the music” of integrin signaling, mechanical inputs “control its volume”. Recent studies measuring the kinetics of ligand-receptor bonds in vitro have identified similar mechanoresponsive activity in murine T cell antigen receptors and in the activating Fc receptor CD16, which is expressed by subsets of natural killer (NK) cells [12–14]. Indeed, a large fraction of contact-dependent receptors may eventually prove to be mechanoresponsive, reflecting joint biochemical-biomechanical constraints on their evolution.

How might one tease apart interdependent biochemical and biomechanical effects within an intercellular interaction? At the single cell level, purely biophysical perturbations are difficult to deliver, and simply deleting cell surface receptors precludes both the biochemical and biophysical effects that depend on them. Investigators are left with genetic or pharmacological strategies designed to alter the physical properties of cells selectively, either by targeting the underlying cytoskeleton or by inhibiting specific mechanically-induced changes in cell surface proteins. Such strategies must be applied with care, however, to guard against the possibility of eliciting secondary effects that might alter the abundance of stimulatory proteins on the plasma membrane. In the face of these uniquely mechanobiological challenges, the field has resorted to reductionist systems that leverage advances in materials science to isolate fundamental biophysical properties.

Hydrogel, the guest star that stole the show

Our current understanding of mechanoimmunology owes a great deal to methods in which the leukocyte targets in question – antigen-presenting cells (APCs), opsonized cells, or phagocytic cargo – are replaced by artificial substrates whose physical properties and chemical functionalization can be varied independently. This enables investigators to isolate biophysical parameters such as rigidity without worrying about confounding changes in stimulatory and/or inhibitory ligand density. Several materials have been applied in this way, such as the synthetic elastomer polydimethyl siloxane (PDMS), which is typically fabricated as an array of flexible micropillars [15], and zinc oxide, which is used to create thin, deformable nanowires [16]. The most pervasive substrate for mechanobiological studies is a hydrogel, commonly made of polyacrylamide or sodium alginate. Hydrogels have the advantage of mimicking the physiological stiffness range of most cells and extracellular matrices (0.1–100 kPa) and are easily derivatized by amine coupling chemistry or non-covalent conjugation. While hydrogels are typically used as planar substrates, they can also be polymerized as cell-sized microspheres [17–19]. This latter approach was recently leveraged to generate cellular “stress balls” to profile the mechanical forces delivered across macrophage and T cell synapses with unprecedented precision [19].

Hydrogel studies from multiple groups have unequivocally established that lymphocytes are mechanosensitive. When coated with the same stimulatory ligands at the same density, stiffer hydrogel substrates induce stronger activation than their softer counterparts [20–23]. This property has been most extensively characterized for T cell activation via the T cell receptor (TCR); in this context, the rigidity of substrates bearing cognate antigen or anti-CD3 crosslinking antibodies controls the amplitude of subsequent proliferative, transcriptional, secretory, and metabolic responses [20–22, 24]. B cells and NK cells exhibit analogous stiffness-sensing properties on substrates coated with their respective activating ligands [18, 23]. Recent work with mouse and human macrophages also demonstrates that phagocytosis (of polyacrylamide microparticles or human red blood cells, respectively) is mechanosensitive [19, 25–27]. The aforementioned force-dependent catch bond formation between immunoreceptors and their ligands is thought to be the basis for mechanotransduction in all of these synaptic interfaces. To elicit mechanical effects in this way, the stimulatory surface (i.e. the target/partner cell) must be rigid enough to resist pulling forces instigated by the leukocyte. This rigidity then tunes, through mechanotransduction pathways, the extent of immune cell activation [22].

The importance of hydrogels, elastomers, and other artificial substrates for revealing the fundamental properties of immune cell mechanotransduction is akin to the role of a guest star (e.g., Kanye West) in amplifying the talents of the main act (Daft Punk). Collaborations of this kind can take recording artists to the next level, but they can also attract controversy. Similarly, hydrogel-based biophysical studies that are focused exclusively on mechanosensing, without thoughtfully designed functional experiments, are often (fairly) criticized as overly artificial or non-physiological. Ultimately, further progress in this field will require strategies for isolating physical parameters in the context of bona fide intercellular interactions. For example, in pioneering work on the mechanobiology of T cell-dendritic cell (DC) synapses, DCs lacking the integrin ligand ICAM-1 were reconstituted with a tail-less version of the protein (ΔTail ICAM-1) that could not bind the cytoskeleton and was therefore more mobile within the membrane [28]. ΔTail ICAM-1 DCs induced lower T-cell proliferation and conjugate formation compared to their wild-type counterparts, mechanistically linking constrained lateral mobility to strong LFA-1-ICAM-1 interactions, and downstream signaling. We posit that innovative approaches such as this will be crucial for promoting the “cross-over” appeal of mechanoimmunology to more biologically motivated audiences.

Harder, better, faster, stronger

Cytotoxic lymphocytes, comprising cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs; e.g., CD8+) and NK cells, destroy their target cells via the secretion of perforin and granzyme molecules across the immunological synapse [1]. These cells play a central role in antitumor immunosurveillance, and their therapeutic enhancement has been shown to improve the outcomes of patients with certain advanced-stage cancers (reviewed in [29]). The importance of target cell rigidity for lymphocyte activation in vitro has raised the possibility that the mechanical properties of cancer cells might influence immunosurveillance in vivo. In line with this, our group recently showed that NK cells and CD8+ CTLs respond to the changing stiffness of human and mouse cancer cells during metastatic dissemination [30].

During the initial colonization of a target organ, many metastatic cell types occupy the perivascular niche, a nutrient-rich microenvironment located on the abluminal surface of blood vessels [31, 32]. To expand successfully in this space, cancer cells activate a biomechanical cascade that drives cell spreading and migration [33]. Key to this invasive process are the myocardin related transcription factors (MRTFA and MRTF-B) [34]. At steady state, MRTFs are sequestered in the cytoplasm via binding to monomeric (globular) G-actin. The cytoskeletal remodeling that occurs during cancer cell spreading and invasion, however, induces the consumption of G-actin. This liberates MRTFs, which move to the nucleus to drive the expression of actin and actin-regulatory factors, further promoting cancer cell invasiveness [34]. Using an in vivo experimental system to measure lung colonization, we found that, contrary to what one would expect for transcription factors that drive invasion, the overexpression of MRTFs inhibited the metastasis of transplanted E0771 breast cancer and B16F10 melanoma cells into C57BL6/J mice. Moreover, depleting CD8+ CTLs or NK cells respectively from both sets of tumor-bearing mice completely reversed this phenotype (i.e., led to increased lung metastasis). These findings indicated that increased MRTF expression paradoxically inhibited metastatic colonization by sensitizing cancer cells to the lytic activity of cytotoxic lymphocytes. This conclusion was supported by in vitro cellular cytotoxicity assays using mouse CTLs, and mouse and human NK cells [30].

Bulk RNA-sequencing analysis of MRTF-overexpressing E0771 and B16F10 cells failed to identify any obvious changes in gene expression that might suggest enhanced immune targeting through biochemical modifications in cancer cells. However, MRTF-overexpressing tumor cells were substantially stiffer, suggesting that the basis of their vulnerability to cytotoxic lymphocytes may have been biophysical rather than biochemical. To confirm this hypothesis, it became necessary to decouple changes in the cytoskeleton (the major regulator of cell stiffness) from the biochemical composition of the cell surface (including lymphocyte activating molecules). We achieved this in two ways: first, by using a genetically encoded actin depolymerizer (DeAct) [35] to weaken the cytoskeleton and reduce cancer cell stiffness; and second, by generating giant plasma membrane vesicles (GPMVs) directly from the cancer cells, which lacked the underlying cytoskeleton, while retaining cell surface proteins) [36]. In both cases, the stimulatory enhancement of MRTF overexpression on cytotoxic lymphocytes was lost: GPMVs from MRTF-overexpressing B16F10 or MCF7 human cancer cell lines activated mouse CD8+ T-cells or human NK cells, respectively, similarly to GPMVs from control cells. Likewise, cancer cell lines overexpressing both MRTF and DeAct were no more stimulatory than cells expressing DeAct alone. Taken together, these results indicated that the MRTF overexpression phenotype resulted from cytoskeletal rigidification rather than from changes in cell surface composition [36]. Hence, in the systems investigated, cytotoxic lymphocytes not only recognized characteristic biochemical features associated with oncogenic transformation but also detected and destroyed cancer cells based on idiotypic mechanical features [30]. This process, which we have termed “mechanosurveillance”, is embodied by Daft Punk’s magnum opus: “Harder, Better, Faster, Stronger” (2001). MRTF-overexpressing metastatic cells are “harder” (i.e., more rigid) than control cells, stimulating lymphocytes “better”, leading to “faster” and more efficient cancer cell lysis, and a “stronger” anti-tumor immune response (Figure 2).

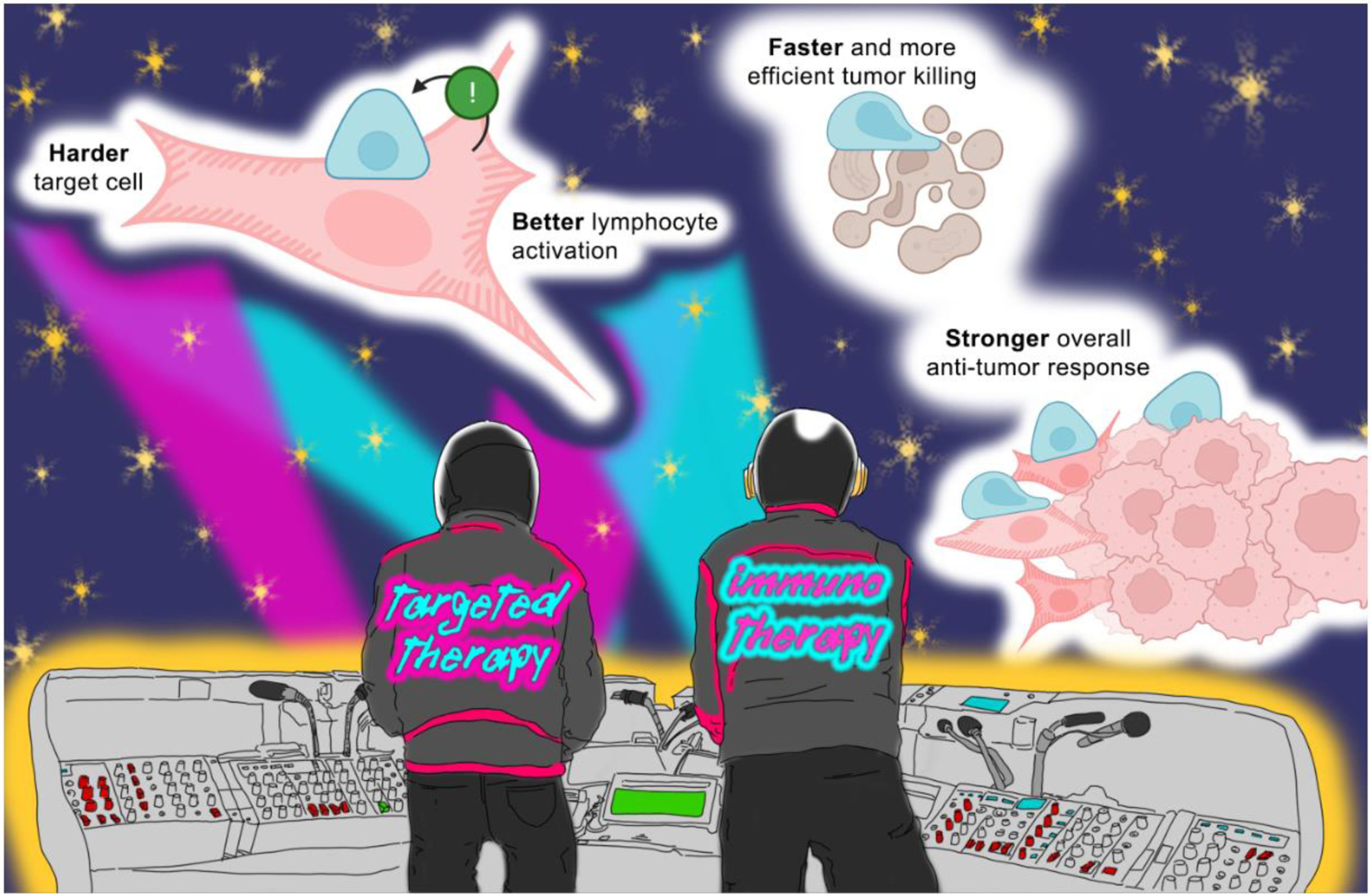

Key Figure, Figure 2. The “Harder, better, faster, stronger” response of antitumor mechanosurveillance.

Schematic representing how “harder” metastatic cells that hyperactivate cytoskeletal pathways (pink with hatching) stimulate lymphocytes (blue) “better”, leading to “faster” cancer cell lysis and a “stronger” anti-tumor immune response compared with tumor cells that do not upregulate these activities (pink without hatching). Targeted molecules and immunotherapies, represented here as the Daft Punk duo, potentiate different aspects of the antitumor response. By acting together, they have the potential to enhance antitumor treatment synergistically.

The mechanosurveillance pathway characterized in our study resulted from changes in the intrinsic biophysical properties of cancer cells induced by MRTF signaling. MRTFs are also mechanoresponsive factors, however, that can be modulated by the extrinsic stiffness of the surrounding microenvironment [34, 37]. Tissue stiffness varies widely in mammals, from 2 kPa (in human lungs) to 2,000 kPa (in bones [38]). In addition, inflammation and pathological conditions such as fibrosis can further alter the biophysical milieu within tissues [39]. These variations in environmental rigidity can be expected to impact the mechanical properties of colonizing cancer cells via MRTF and other mechanosensing circuits [33, 40], leading in turn to the amplification or suppression of mechanosurveillance. This sets up an interesting paradigm in which tissue stiffness might influence metastatic site preference by controlling the capacity of cancer cells to resist immune-mediated attack. In line with this, environmental stiffness might also impact the activities of infiltrating immune cells directly, apart from target rigidity, as discussed above. For instance, murine (RAW 264.7) or primary human alveolar macrophages seeded on stiffer substrates (150 kPa, similar to mouse fibrotic lung tissue) exhibit increased uptake of IgG-opsonized latex beads and bacteria (Mycobacterium bovis) compared to cells seeded on softer substrates (1.2 kPa, similar to mouse lung tissue) [41]. Analogous observations have been made in a model of naïve T-cell activation [42, 43]. Upon encountering stimulatory beads, mouse CD4+ T cells seeded in rigid (40 kPa) alginate-based 3D scaffolds proliferated and secreted more proinflammatory cytokines compared to cells activated within softer scaffolds (4 kPa). In these experiments, the stimulatory signals were presented on beads of static stiffness, demonstrating that the activation of naïve T cells was mechanically responsive to the environment independently of the biochemical and biophysical properties of the antigen-presenting surface. The nexus of microenvironmental rigidity, immunosurveillance, and metastatic site preference highlighted by these studies, remains an intriguing topic for future work.

The applicability of mechanosurveillance to other immune cells and target cell types is another area of interest. Macrophages are known to phagocytose stiff material (e.g., 7-kPa hydrogel particles or 250-kPa fixed red blood cells (RBCs)) more efficiently than soft material (e.g., 0.3-kPa hydrogels or 3-kPa native RBCs) (reviewed in [44]). Little is known, however, about the interplay between biophysics and biochemical signaling in the decision to phagocytose a host cell [27]. The existence of such crosstalk would add a heretofore-unappreciated mechanical dimension to cancer cell engulfment and degradation.

It will also be interesting to explore how differentiation states of target cells (i.e., dormancy and senescence) exhibit distinct morphological phenotypes that can be acted upon by immune cells. Morphological analyses of human lung and breast carcinoma cells in the metastatic niche have shown that dormant cancer cells adopt more rounded architectures and display lower MRTF signaling than their proliferative counterparts [33, 45]. We hypothesize that a state of dormancy also results in reduced cell stiffness, which could potentially contribute to immune discrimination of cell cycle states within tumor cell populations. Biochemically, dormancy in human cancer cells appears to confer resistance to NK cell-mediated killing via downmodulation of NK cell ligands [45]; however, it is tempting to speculate that the potentially softer dormant cancer cells might also be intrinsically less stimulatory because of reduced mechanical stimulation of cytotoxic lymphocytes.

Cellular senescence, in contrast to normal cell cycle, has been associated with both increased F-actin and cortical rigidity in mouse models of aging and progeria [46, 47]. The timely clearance of senescent cells is crucial for the homeostasis of most organs, and recent work has revealed a role for cellular cytotoxicity in this process [48]. According to our hypothesis, the rigidification of senescent cells might enhance the selectivity of their own clearance by cytotoxic lymphocytes, which would be expected to spare the softer, healthy dividing cells. The extent to which the biophysical properties of senescent cells earmark them to be destroyed, however, remains unknown.

Finally, a number of intracellular pathogens, including Listeria sp., Chlamydia sp., and HIV-1, actively remodel the host cytoskeleton as part of their infectious cycles [49–51]. The resulting changes in host cell architecture are drastic, fueling the hypothesis that these infections might also induce biophysical changes that are subject to lymphocyte mechanosurveillance. Conversely, some infectious agents might modulate the mechanical properties of host cells to avoid immune detection (i.e., by reducing their rigidity or by increasing the lateral mobility of surface proteins). In this context, virally or bacterially induced cortical softening might function as the biophysical equivalent of canonical biochemical mechanisms of immune escape, such as the downregulation of MHC or CD28 in human host cells induced by the HIV-1 protein Nef [52, 53]. Future studies are warranted to shed light on these intriguing possibilities.

The phenomenon of mechanosurveillance widens the conceptual purview of mechanoimmunology within basic science, much as Daft Punk has expanded the appreciation of electronic music beyond the niche club scene. Nevertheless, one place in which Daft Punk is not yet frequently heard is in a hospital elevator: are there exciting prospects for mechanoimmunology in clinical settings? We explore this question below.

The next big single: Human After All (Reprise)

ICB therapy employs neutralizing antibodies against inhibitory cell surface receptors (e.g. CTLA-4 and PD-1) to release the biochemical brakes on T cells [4]. Arguably the most promising development in cancer therapy in the last 20 years, ICB has transformed the treatment of metastatic melanoma and non-small cell lung cancer. Many patients fail to respond, however, indicating that more work must be done to augment the potency and applicability of this approach. In our recent study, mice injected with MRTF-overexpressing B16F10 tumors survived better and exhibited reduced lung colonization when treated with anti-PD-1 or anti-CTLA-4 antibodies compared to treated mice bearing control tumors, indicating that MRTF overexpression sensitized cancer cells to ICB [30]. We also found that the human melanomas bearing the RacP29S mutation, which exhibited high MRTF signaling (by transcriptomic analysis), were more responsive to ICB therapy [30]. These results suggested that mechanosurveillance might synergize with treatment strategies designed to boost the activity of cytotoxic lymphocytes. They also highlight the potential value of MRTF proteins as putative markers to predict, and/or targets to enhance, the efficacy of ICB in the clinic.

Using MRTFs as candidate prognostic markers will require that their activity be measured in tumors. In our recent study [30], we used the RacP29S mutation [54] as a proxy to identify human melanomas with high MRTF activity. Interrogating this pathway further will require approaches that assess the status of MRTF signaling more directly. MRTF-A and MRTF-B immunohistochemical staining would be expected to reveal the expression of both proteins and their nuclear localization [34]. One could also mine tumor-derived transcriptomic data for the up- and downregulation of MRTF target genes. Ideally, these expression-based approaches would be complemented by direct biophysical measurements of the tumor microenvironment. AFM analysis of tissue sections [55], while well-established as a research method, may be difficult to incorporate into routine clinical diagnostics. However, newer, more applicable tools exist, such as magnetic resonance elastography (MRE), a macroscopic noninvasive imaging approach that is currently used for tumor diagnosis [56]. Mechanosensing during immune cell interactions ultimately occurs at the cellular level, and thus, measuring the physical properties of living tissues and single cells on a cellular length scale might be more relevant to address the clinical applicability of mechanosurveillance (techniques reviewed in [57]). Moreover, some techniques such as microfluidic-based cell distortion now allow for high-throughput analyses [58]. Developing these methods for macro- and microscopic evaluation of human samples could facilitate the prompt translation of mechanobiological discoveries to the clinic.

The mechanosurveillance model described here predicts that tumors with higher MRTF activity and cell-intrinsic rigidity might respond better to immunotherapy than softer tumors. This expectation contrasts sharply with established associations between MRTF signaling and targeted small molecule treatments. For example, MRTF hyperactivation by RacP29S mutation or drug-induced transcriptional reprogramming renders melanoma cells resistant to BRAF inhibitors in vitro and in vivo [54, 59]. One proposed explanation for this effect is that MRTF-dependent tumor stiffening creates a denser extracellular matrix, which acts as a diffusional barrier limiting the access of therapeutic molecules [59]. Whether this stiffened environment might also promote ICB-induced mechanosurveillance has not been investigated. Multiple clinical studies, however, have demonstrated synergy between BRAF inhibitors and ICB (reviewed in [60]). The basis for this effect seems to be in part biochemical: BRAF inhibition can increase antigen presentation and the expression of activating NK cell ligands [61–63]. The contribution of tumor cell mechanics nonetheless needs to be investigated, as approaches to biochemically inducing mechanical reprogramming could potentially widen the window of opportunity for ICB treatment in patients refractory to classical targeted therapies. In this regard, screening current therapies for collateral changes in the biophysical properties of cancer cells (or of their tissue environments) might identify treatments to combine or avoid with ICB, depending on their effects on cancer cell stiffness. As we seek to broaden the power and scope of immunotherapy, it will be important to keep in mind the interdependence between the biochemical and biophysical components of tumor immunity. It is our hope that, by properly accounting for both of these facets of the anti-tumor response, we will “Get Lucky” (2013) with the right treatment combinations to top the medical charts “Around the World” (1997).

Concluding remarks

Over the last two decades, cellular mechanics has emerged as a key regulator of the immune response. We argue that these mechanics are particularly important during antitumor immunosurveillance, wherein cytotoxic lymphocyte mechanosensing of cancer cell stiffness can induce vigorous destruction of metastatic tumors. However, there is much more work to be done in this area. For one, we remain unsure of the relative contributions of cell-intrinsic and environmental mechanics to biophysical vulnerabilities in relevant disease models. Moreover, the extent to which mechanosurveillance affects the earlier stages of cancer progression or mediates the clearance of other dysregulated cell types (see Outstanding Questions) is unknown. To address these questions and determine the relevance of mechanosurveillance for human disease, it will be necessary to develop more ways to accurately measure and tune the biophysical properties of cells and tissues in vitro and in vivo. A wider and more flexible toolkit to elucidate the principles of mechanoimmunology in model organisms and patient samples simultaneously would facilitate the identification of crucial mechanoregulators of antitumor responses and open future translational opportunities. We have made clear how the Daft Punk classic “Harder, Better, Faster, Stronger” encapsulates our working model for antitumor immunosurveillance. To us, this song also reflects the germinal state of mechanoimmunology and the exciting puzzles that lie ahead, with its poignant but resonant ending line: “our work is never over”.

Outstanding Questions Box.

What is the contribution of ‘environmental stiffness’ to mechanosurveillance? Substrate stiffness alters the biophysical properties of cancer cells in vitro, but whether the same holds true in the tumor microenvironment remains unclear.

Besides metastasis, are cancer cells in earlier stages of disease progression susceptible to mechanosurveillance? Does the mechanical status of cancer cells in primary tumors protect them from or sensitize them to immune attack?

Are immune cell types other than cytotoxic lymphocytes involved in mechanosurveillance? Macrophages and neutrophils are two obvious candidates for this type of detection mechanism.

Do current anti-cancer treatments affect the biophysical properties of tumor cells, and if so, how? Do these effects synergize with immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) therapy? The documented synergy between BRAF inhibitors and ICB in melanoma would be an obvious place to start looking.

What are the key drivers of tumor cell rigidity (other than MRTF), and can they be targeted to promote anti-tumor immunotherapy? Cytoskeletal adaptors and regulators of membrane-cytoskeleton interactions seem to be obvious candidates.

Does the immune system employ mechanosurveillance to identify and eliminate virally or bacterially infected cells? Conversely, have intracellular pathogens evolved strategies to escape mechanosurveillance?

Is mechanosurveillance involved in the clearance of senescent cells? The documented morphological changes that accompany senescence are quite intriguing in this respect.

Highlights.

Immune responses are canonically triggered by biochemical signals. Many immunoreceptors, however, are mechanosensitive, and thus rely on the mechanical forces generated at cell-to-cell contacts to achieve full signaling capacity.

Materials that mimic the mechanical properties of cells are useful for delineating the contribution of biophysical inputs to immune activation. As with all artificial systems, however, results must be interpreted with care.

Mechanotransduction is particularly relevant for cytotoxic lymphocyte responses against metastatic cancer cells. As such, cytoskeletal regulators such as myocardin-related transcription factors (MRTFs) might serve as prognostic markers and targets for immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) therapy.

Small-molecule therapies can induce mechanical reprogramming of tumor cells and elicit resistance mechanisms. In these cases, targeting emergent biophysical vulnerabilities of the tumor with immunotherapy might improve treatment outcomes.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ekrem Emrah Er for critical reading of the manuscript, members of the Huse lab for advice, and Guy-Manuel de Homem-Christo and Thomas Bangalter for inspiration. Supported in part by the National institutes of Health (R01-AI087644 to M. H.), the Ludwig Center at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (to M.T-L.), the Center for Experimental Immuno-oncology and Comedy vs Cancer (to M.T-L.), and the Bruce Charles Forbes Pre-Doctoral Fellowship from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (to M.D.J.). Certain figure elements were taken or modified from Biorender graphical assets.

Glossary

- Actomyosin cytoskeletal network

The predominantly cortical assembly of filamentous actin and myosin II that controls cell shape and force exertion against the environment.

- Atomic force microscopy (AFM)

biophysical approach in which a flexible cantilever is used to measure the deformability of a sample.

- BRAF inhibitors

Small molecules used as an anti-cancer therapy in patients with tumors bearing the hyperactive BRAF V600E mutation.

- Catch-bond

non-covalent interaction whose affinity increases under applied force until an optimal force is reached, after which the affinity decreases.

- Deformable nanowires

Microscale, malleable zinc oxide wires designed to present stimulatory ligands in a complex, three dimensional environment.

- Dormancy

cellular state in which metastatic cancer cells, often after oncologic treatment, enter cycle arrest and survive for prolonged times. Dormant cells can, under favorable conditions, begin cycling again to generate new metastatic colonies.

- Environmental stiffness

The rigidity of a cell’s surroundings determined by cell-extrinsic elements in tissues such as the extracellular matrix (ECM).

- Force clamp technology

collection of biophysical methods that use feedback circuits to maintain biological or chemical samples (e.g. cells or molecules) under constant, user-defined tension.

- Giant plasma membrane vesicles (GPMVs)

Large unilamellar vesicles derived from the plasma membrane that are devoid of cortical cytoskeletal structures.

- Hydrogel

hydrophilic polymer network whose physical and chemical properties can be tuned experimentally.

- Idiotypic mechanical features

Characteristic biophysical properties that can be used to identify a cell of interest.

- Immune checkpoint blockade

Immunotherapeutic strategies that aim to countermand the negative regulators of immune activation, leading to enhanced responses against cancer cells.

- Immunological synapses

Intercellular contacts formed by immune cells with each other or with non-immune cells. Secreted biomolecules or mechanical forces can be transmitted directionally and specifically through these contacts

- Magnetic resonance elastography (MRE)

Technology that combines magnetic resonance imaging with low-frequency vibrations to quantitatively measure the mechanical properties of tissues non-invasively.

- Mechanotransduction

cellular signaling process in which mechanical stimuli are converted into biochemical outputs.

- Microfluidic-based cell distortion

class of methods that use liquid flow in microfluidic chambers to distort cells and thereby measure their deformability.

- Outside-in complexes

Signal transduction complexes that assemble around ligand bound integrin tails and the core adaptor protein talin. These complexes transduce “outside-in” signals that regulate cellular activation, gene expression, and proliferation.

- Polydimethyl siloxane (PDMS)

silicon-based organic polymer that is flexible and can be easily fabricated to adopt multiple configurations and exhibit a wide range of mechanical properties.

- Senescence

cellular process that typically occurs with aging, in which cells stop dividing without undergoing cell death.

- Stereotypic intercellular contacts

Cell-cell interactions exhibiting characteristic structure and function.

- t-SNE plots

Graphs visually representing high-dimensional data on a human-readable display (usually 2 axes), utilizing the statistical method of t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE). They are commonly used to represent single-cell RNA sequencing data.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Resources

Daft Punk- Harder Better Faster Stronger (Official Video): https://youtu.be/x84m3YyO2oU

References

- 1.Dustin ML and Long EO (2010) Cytotoxic immunological synapses. Immunol Rev 235 (1), 24–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Freeman SA and Grinstein S (2014) Phagocytosis: receptors, signal integration, and the cytoskeleton. Immunol Rev 262 (1), 193–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harwood NE and Batista FD (2010) Early events in B cell activation. Annu Rev Immunol 28, 185–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wei SC et al. (2018) Fundamental Mechanisms of Immune Checkpoint Blockade Therapy. Cancer Discov 8 (9), 1069–1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huse M (2017) Mechanical forces in the immune system. Nature Reviews Immunology 17 (11), 679–690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhu C et al. (2019) Mechanosensing through immunoreceptors. Nature Immunology 20 (10), 1269–1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen W et al. (2010) Forcing switch from short- to intermediate- and long-lived states of the alphaA domain generates LFA-1/ICAM-1 catch bonds. J Biol Chem 285 (46), 35967–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kong F et al. (2009) Demonstration of catch bonds between an integrin and its ligand. J Cell Biol 185 (7), 1275–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosetti F et al. (2015) A Lupus-Associated Mac-1 Variant Has Defects in Integrin Allostery and Interaction with Ligands under Force. Cell Rep 10 (10), 1655–1664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.del Rio A et al. (2009) Stretching single talin rod molecules activates vinculin binding. Science 323 (5914), 638–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Friedland JC et al. (2009) Mechanically activated integrin switch controls alpha5beta1 function. Science 323 (5914), 642–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gonzalez C et al. (2019) Nanobody-CD16 Catch Bond Reveals NK Cell Mechanosensitivity. Biophys J 116 (8), 1516–1526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu B et al. (2014) Accumulation of dynamic catch bonds between TCR and agonist peptide-MHC triggers T cell signaling. Cell 157 (2), 357–368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu KH and Butte MJ (2016) T cell activation requires force generation. J Cell Biol 213 (5), 535–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bashour KT et al. (2014) CD28 and CD3 have complementary roles in T-cell traction forces. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111 (6), 2241–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bhingardive V et al. (2021) Antibody-Functionalized Nanowires: A Tuner for the Activation of T Cells. Nano Lett 21 (10), 4241–4248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Traber N et al. (2019) Polyacrylamide Bead Sensors for in vivo Quantification of Cell-Scale Stress in Zebrafish Development. Sci Rep 9 (1), 17031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Friedman D et al. (2021) Natural killer cell immune synapse formation and cytotoxicity are controlled by tension of the target interface. J Cell Sci 134 (7) :jcs258570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vorselen D et al. (2020) Microparticle traction force microscopy reveals subcellular force exertion patterns in immune cell-target interactions. Nat Commun 11 (1), 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blumenthal D et al. (2020) Mouse T cell priming is enhanced by maturation-dependent stiffening of the dendritic cell cortex. Elife 9 :e55995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Judokusumo E et al. (2012) Mechanosensing in T lymphocyte activation. Biophys J 102 (2), L5–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saitakis M et al. (2017) Different TCR-induced T lymphocyte responses are potentiated by stiffness with variable sensitivity. Elife 6 :e23190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wan ZP et al. (2013) B Cell Activation Is Regulated by the Stiffness Properties of the Substrate Presenting the Antigens. Journal of Immunology 190 (9), 4661–4675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O’Connor RS et al. (2012) Substrate rigidity regulates human T cell activation and proliferation. J Immunol 189 (3), 1330–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beningo KA and Wang YL (2002) Fc-receptor-mediated phagocytosis is regulated by mechanical properties of the target. J Cell Sci 115 (Pt 4), 849–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jaumouille V et al. (2019) Coupling of beta2 integrins to actin by a mechanosensitive molecular clutch drives complement receptor-mediated phagocytosis. Nat Cell Biol 21 (11), 1357–1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sosale NG et al. (2015) Cell rigidity and shape override CD47’s “self”-signaling in phagocytosis by hyperactivating myosin-II. Blood 125 (3), 542–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Comrie WA et al. (2015) The dendritic cell cytoskeleton promotes T cell adhesion and activation by constraining ICAM-1 mobility. J Cell Biol 208 (4), 457–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Finn OJ (2018) A Believer’s Overview of Cancer Immunosurveillance and Immunotherapy. J Immunol 200 (2), 385–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tello-Lafoz M et al. (2021) Cytotoxic lymphocytes target characteristic biophysical vulnerabilities in cancer. Immunity 54 (5), 1037–1054 e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ghajar CM et al. (2013) The perivascular niche regulates breast tumour dormancy. Nat Cell Biol 15 (7), 807–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kienast Y et al. (2010) Real-time imaging reveals the single steps of brain metastasis formation. Nat Med 16 (1), 116–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Er EE et al. (2018) Pericyte-like spreading by disseminated cancer cells activates YAP and MRTF for metastatic colonization. Nat Cell Biol 20 (8), 966–978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gau D and Roy P (2018) SRF’ing and SAP’ing - the role of MRTF proteins in cell migration. J Cell Sci 131 (19) :jcs218222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harterink M et al. (2017) DeActs: genetically encoded tools for perturbing the actin cytoskeleton in single cells. Nat Methods 14 (5), 479–482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sezgin E et al. (2012) Elucidating membrane structure and protein behavior using giant plasma membrane vesicles. Nat Protoc 7 (6), 1042–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hadden WJ et al. (2017) Stem cell migration and mechanotransduction on linear stiffness gradient hydrogels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114 (22), 5647–5652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guimaraes CF et al. (2020) The stiffness of living tissues and its implications for tissue engineering. Nature Reviews Materials 5 (5), 351–370. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang S and Plotnikov SV (2021) Mechanosensitive Regulation of Fibrosis. Cells 10 (5):994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van Helvert S et al. (2018) Mechanoreciprocity in cell migration. Nat Cell Biol 20 (1), 8–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Patel NR et al. (2012) Cell elasticity determines macrophage function. PLoS One 7 (9), e41024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Majedi FS et al. (2020) T-cell activation is modulated by the 3D mechanical microenvironment. Biomaterials 252 :120058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Meng KP et al. (2020) Mechanosensing through YAP controls T cell activation and metabolism. J Exp Med 217 (8) :e20200053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vorselen D et al. (2020) A mechanical perspective on phagocytic cup formation. Curr Opin Cell Biol 66, 112–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Malladi S et al. (2016) Metastatic Latency and Immune Evasion through Autocrine Inhibition of WNT. Cell 165 (1), 45–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mu X et al. (2020) Cytoskeleton stiffness regulates cellular senescence and innate immune response in Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria Syndrome. Aging Cell 19 (8), e13152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ferrari S and Pesce M (2021) Stiffness and Aging in Cardiovascular Diseases: The Dangerous Relationship between Force and Senescence. Int J Mol Sci 22 (7) :3404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ovadya Y et al. (2018) Impaired immune surveillance accelerates accumulation of senescent cells and aging. Nat Commun 9 (1), 5435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bhavsar AP et al. (2007) Manipulation of host-cell pathways by bacterial pathogens. Nature 449 (7164), 827–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Taylor MP et al. (2011) Subversion of the actin cytoskeleton during viral infection. Nat Rev Microbiol 9 (6), 427–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wesolowski J and Paumet F (2017) Taking control: reorganization of the host cytoskeleton by Chlamydia. F1000Res 6, 2058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Leonard JA et al. (2011) HIV-1 Nef disrupts intracellular trafficking of major histocompatibility complex class I, CD4, CD8, and CD28 by distinct pathways that share common elements. J Virol 85 (14), 6867–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jia X et al. (2012) Structural basis of evasion of cellular adaptive immunity by HIV-1 Nef. Nat Struct Mol Biol 19 (7), 701–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lionarons DA et al. (2019) RAC1(P29S) Induces a Mesenchymal Phenotypic Switch via Serum Response Factor to Promote Melanoma Development and Therapy Resistance. Cancer Cell 36 (1), 68–83 e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shen Y et al. (2020) Protocol on Tissue Preparation and Measurement of Tumor Stiffness in Primary and Metastatic Colorectal Cancer Samples with an Atomic Force Microscope. STAR Protoc 1 (3), 100167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yang JY and Qiu BS (2021) The Advance of Magnetic Resonance Elastography in Tumor Diagnosis. Front Oncol 11, 722703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gomez-Gonzalez M et al. (2020) Measuring mechanical stress in living tissues. Nature Reviews Physics 2 (6), 300–317. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Urbanska M et al. (2020) A comparison of microfluidic methods for high-throughput cell deformability measurements. Nat Methods 17 (6), 587–593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Girard CA et al. (2020) A Feed-Forward Mechanosignaling Loop Confers Resistance to Therapies Targeting the MAPK Pathway in BRAF-Mutant Melanoma. Cancer Res 80 (10), 1927–1941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Naderi-Azad S and Sullivan R (2020) The potential of BRAF-targeted therapy combined with immunotherapy in melanoma. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther 20 (2), 131–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Frederick DT et al. (2013) BRAF Inhibition Is Associated with Enhanced Melanoma Antigen Expression and a More Favorable Tumor Microenvironment in Patients with Metastatic Melanoma. Clinical Cancer Research 19 (5), 1225–1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hu-Lieskovan S et al. (2015) Improved antitumor activity of immunotherapy with BRAF and MEK inhibitors in BRAF(V600E) melanoma. Sci Transl Med 7 (279), 279ra41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Frazao A et al. (2020) BRAF inhibitor resistance of melanoma cells triggers increased susceptibility to natural killer cell-mediated lysis. J Immunother Cancer 8 (2) :e000275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]