Abstract

Elevated plasma levels of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) are documented in patients with sepsis and levels positively correlate with disease severity and mortality. Our previous work demonstrated that visceral adipose tissues (VAT) are a major source of PAI-1, especially in the aged (murine endotoxemia), that circulating PAI-1 protein levels match the trajectory of PAI-1 transcript levels in VAT (clinical sepsis), and that PAI-1 in both VAT and plasma are positively associated with acute kidney injury (AKI) in septic patients. In the current study utilizing preclinical sepsis models, PAI-1 tissue distribution was examined and cellular sources as well as mechanisms mediating PAI-1 induction in VAT were identified. In aged mice with sepsis, PAI-1 gene expression was significantly higher in VAT than in other major organs. VAT PAI-1 gene expression correlated with PAI-1 protein levels in both VAT and plasma. Moreover, VAT and plasma levels of PAI-1 were positively associated with AKI markers, modeling our previous clinical data. Using explant cultures of VAT, we determined that PAI-1 is secreted robustly in response to recombinant TGFβ and TNFα treatment; however, neutralization was effective only for TNFα indicating that TGFβ is not an endogenous modulator of PAI-1. Within VAT, TNFα was localized to neutrophils and macrophages. PAI-1 protein levels were 4-fold higher in stromal vascular fraction (SVF) cells compared to mature adipocytes, and among SVF cells, both immune and non-immune compartments expressed PAI-1 in similar fashion. PAI-1 was localized predominantly to macrophages within the immune compartment and preadipocytes and endothelial cells within the non-immune compartment. Collectively, these results indicate that induction and secretion of PAI-1 from VAT is facilitated by a complex interaction among immune and non-immune cells. As circulating PAI-1 contributes to AKI in sepsis, understanding PAI-1 regulation in VAT could yield novel strategies for reducing systemic consequences of PAI-1 overproduction.

Keywords: adipose tissue, aging, kidney injury, PAI-1, sepsis

1. INTRODUCTION

Sepsis is an infection-initiated clinical syndrome characterized by a dysregulated host response and life-threatening organ dysfunction (M. Singer et al., 2016). Despite poor public recognition, sepsis is a serious public health concern and a leading cause of death worldwide with a mortality rate of approximately 20–30% (Elixhauser, Friedman, & Stranges, 2011; Fleischmann et al., 2016; Xu, Murphy, Kochanek, & Bastian, 2016). Importantly, sepsis is a syndrome which primarily affects people at late middle-age to old age (Angus et al., 2001; Gorina, Hoyert, Lentzner, & Goulding, 2005; Martin, Mannino, & Moss, 2006; Starr & Saito, 2014). Factors contributing to susceptibility of older patients to sepsis include age-dependent structural and functional changes of the major organs, higher number of comorbidities, increased incidence of infection, and an increased need for invasive procedures (Chronopoulos, Rosner, Cruz, & Ronco, 2010). Despite the clear link between aging and development of sepsis, the majority of preclinical studies are carried out using very young animals, the human equivalent of a teenager (Rittirsch, Hoesel, & Ward, 2007; Starr & Saito, 2014). While these studies with young mice have certainly increased our knowledge of sepsis, important information specific to the pathophysiology of sepsis in old age is likely missing. Solving this problem is urgent, as the U.S. population is rapidly aging (Newgard & Sharpless, 2013). As effective interventions to reduce sepsis-related tissue injury remain unavailable (Cohen et al., 2015; Gómez, Kellum, & Ronco, 2017; Vignon, Laterre, Daix, & François, 2020), understanding the age-specific mechanisms leading to organ injury are crucial to reducing sepsis-related morbidity and mortality.

Plasminogen activator inhibitor-type 1 (PAI-1) is a major natural inhibitor of intravascular fibrinolysis. By inhibiting clot breakdown, PAI-1 promotes thrombosis, ischemia, and tissue damage during sepsis (Eddy, 2002; Levi & Poll, 2015; Levi & van der Poll, 2017). Elevated circulating levels of PAI-1 are observed in patients with sepsis and high levels correlate with disease severity and mortality (Hoppensteadt et al., 2015; Kinasewitz et al., 2004; Lorente et al., 2014; Madoiwa et al., 2006; Pralong et al., 1989; Tipoe et al., 2018; Zwischenberger et al., 2020); however, the mechanisms leading to increased PAI-1 during sepsis are largely unknown. Preclinical models of sepsis, likewise, show elevated PAI-1 in circulation as well as in various cells and organs (Gupta, Xu, Castellino, & Ploplis, 2016; Raeven et al., 2012; Samad, Yamamoto, & Loskutoff, 1996; Sawdey & Loskutoff, 1991; Starr et al., 2013; Starr, Steele, Cohen, & Saito, 2016; Starr et al., 2015; Swarbreck et al., 2015). More specifically, animal studies have shown that PAI-1 contributes to renal fibrin deposition (Gupta, Donahue, Sandoval-Cooper, Castellino, & Ploplis, 2015; Miyaji et al., 2003; Montes et al., 2000; Yamamoto et al., 2002). We previously reported, using models of endotoxemia (Starr et al., 2010), polymicrobial abdominal sepsis (Starr et al., 2015), and acute pancreatitis (Okamura et al., 2012) that aged mice show far more profound fibrin deposition in the lung, liver, and kidney, likely contributing to more pronounced organ injury and mortality in this vulnerable population. Indeed, PAI-1 is recognized as one of the key factors in aging-associated thrombotic diseases (Yamamoto, Takeshita, Kojima, Takamatsu, & Saito, 2005).

Among the major organs, visceral adipose tissues (VAT) are a major source of PAI-1 transcript in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-injected aged mice, with mRNA levels far exceeding that of liver and kidney (Starr et al., 2013). Moreover PAI-1 levels in VAT of aged mice are more than double that of young-adult mice (Starr et al., 2013). We recently confirmed that patients with sepsis also show profound PAI-1 induction in multiple VAT depots and that the trajectory of circulating PAI-1 matched PAI-1 transcript levels in VAT (Zwischenberger et al., 2020). Interestingly, we also found that PAI-1 levels in VAT and plasma were positively associated with markers of acute kidney injury (AKI), including creatinine and blood urea nitrogen (BUN). This finding is clinically relevant as incidence of AKI in septic patients is high and associated with increased morbidity and mortality (Hoste et al., 2015; Neyra et al., 2018; Rewa & Bagshaw, 2014). Our data collectively suggest that high circulating PAI-1 levels in sepsis are related to increased PAI-1 production by VAT. Indeed, others have shown clear associations between fat mass or weight loss, VAT levels of PAI-1, and circulating levels of PAI-1, indicating that the visceral fat depot is of importance regarding plasma PAI-1 levels (Alessi et al., 2000; Ekström, Liska, Eriksson, Sverremark-Ekström, & Tornvall, 2012; Janand-Delenne et al., 1998; Mavri et al., 1999; Shimomura et al., 1996).

In the current study, we revert back to preclinical sepsis models and ex vivo assays to: 1) demonstrate that our recent clinical findings in patients with abdominal sepsis can be replicated in polymicrobial sepsis models, 2) to gain an understanding of how PAI-1 is regulated in VAT, and 3) to ascertain which cell populations within VAT contribute to PAI-1 induction during sepsis.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Animals and husbandry

Aged male C57BL/6 mice were obtained from the National Institute on Aging at 12 and 21–24 months of age. These mice are the human equivalent of people at 40–45 and 60–70 years of age, respectively (Flurkey, Currer, & Harrison, 2007). All mice were housed in pressurized intraventilated (PIV) cages with free access to drinking water and chow (Teklad Global No. 2918) and maintained in an environment under controlled temperature (21–23°C), humidity (30–70%), and lighting (14 hours/10 hours, light/dark). All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Kentucky and performed in accord with the National Institutes of Health guidelines for ethical animal treatment.

2.2. Sepsis models

Cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) model: CLP was performed as previously described (Starr et al., 2015). Briefly, mice were anesthetized by isoflurane inhalation, the abdominal cavity was opened, and the distal 1 cm of the cecum ligated with suture and punctured twice with a 21-gauge needle. Sham-operated mice received the same procedures except for ligation and puncture. All mice received 1mL saline (subcutaneously, s.c.) immediately after surgery. Cecal slurry (CS) model: Polymicrobial sepsis was initiated by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of CS (300uL (30mg) for 12 month old mice and 200–250uL (20–25mg) for 21–24 month old mice), prepared as previously described in detail (Starr et al., 2014) with minor refinements as noted in Steele et al. (Steele, Starr, & Saito, 2017), at a dose which would be 100% lethal when administered without subsequent therapeutic resuscitation. Antibiotics (imipenem, IPM; 1.5 mg/mouse, i.p.) and fluid resuscitation (saline 0.9%) were administered beginning 12h following CS injection and continued twice daily until euthanasia. Control mice (0h time-point) received vehicle injection (10% glycerol, i.p.). For both models, body temperature, a parameter for the severity of sepsis, was assessed by rectal temperature probe with a digital thermometer (Digi-Sense, Kent Scientific); mice which did not develop severe hypothermia (<30°C) were excluded from the study.

2.3. Sample collection

Mice were deeply anesthetized by isoflurane inhalation, laparotomy performed, and blood collected from the inferior vena cava by syringe needle with 10% volume of 0.1M sodium citrate. Subsequently, the inferior vena cava was cut, and the entire vasculature was perfused with physiological saline through the cardiac ventricles, for the purpose of eliminating circulating cells. For protein and gene expression analyses, each tissue (heart, liver, kidney, spleen, epididymal fat, mesenteric fat, retroperitoneal fat, subcutaneous fat) was carefully dissected, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C. Collected blood was immediately centrifuged (2,500 × g, 4°C, 15 minutes) to obtain plasma which was stored at −80°C. For explant cultures and tissue dissociation studies, fresh epididymal adipose tissues were dissected and placed on ice prior to processing. No perfusion was performed in mice used for explant cultures.

2.4. RNA purification and quantitative RT-PCR

Frozen tissues were homogenized with TRIzol reagent following the standard protocol with one modification: for adipose tissues, prior to the addition of chloroform the homogenate was centrifuged (9,400 × g, 4°C, 10 minutes) and the upper lipid layer removed. Total cellular RNA was purified using PureLink RNA MiniKit (Invitrogen), the concentration determined by reading the absorbance at 260, and the 260:280 ratio was used to access RNA purity (NanoDrop). Equivalent amounts of RNA were reverse transcribed into cDNA (SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis SuperMix, Life Technologies). Primers were designed using the Universal Probe Library (Roche) and purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies. The reaction was performed on a Roche Light Cycler 480 machine using the hydrolysis probe format with LightCycler 480 Probes Master mix. Target gene expression was normalized to 18S expression as an endogenous control. Fold change was calculated as 2−(ΔΔCT), using the mean ΔCT of the control group as a calibrator. Forward and reverse primer sequences are as follows (5’ to 3’): PAI-1 (aggatcgaggtaaacgagagc and gcgggctgagatgacaaa); 18S (aaatcagttatggttcctttggtc and gctctagaattaccacagttatccaa).

2.5. Protein extraction and Western blot analyses

Protein was extracted as recently described (Zwischenberger et al., 2020). Protein isolates (5–10 μg) were resolved by SDS-PAGE electrophoresis (Bio-Rad Mini PROTEAN Tetra system) using TGX stain-free gradient (4–15%) gels, total protein was visualized using stain-free technology (ChemiDoc MP imaging system), and proteins were electrophoretically transferred (Bio-Rad Trans-blot Turbo Transfer System) to polyvinylidenedifluoride (pvdf) membranes. The membranes were blocked for 1 hr in 3% non-fat dry milk at room temperature, and incubated in primary antibody in 1% non-fat dry milk overnight at 4°C. HRP-linked secondary antibody incubation (Santa Cruz #SC-2004, 1:10,000 dilution) was conducted for 1 hr at room temperature, and the reaction was detected by chemiluminescence (Bio-Rad Clarity Western ECL Substrate). Primary antibodies were as follows: anti-PAI-1 antibody (Abcam ab182973, 1:5,000), anti-CD45 (Abcam, ab10558, 1:1,000), anti-CD11b (Abcam ab133357, 1:1,000), anti-CD3 (Abcam ab16669, 1:500), anti-CD31 (Invitrogen PA5-16301, 1:500), anti-CD34 (Invitrogen PA5-89536, 1:500). Densitometry analysis was performed on the resulting blots using Image Lab software, and normalized by total protein analysis.

2.6. Assessment of kidney injury

Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) in plasma was assessed by ELISA according to the manufacturer’s protocol (R&D Systems, MLCN20).

2.7. Adipose tissue explant cultures

Excised epidydimal fat pads from aged mice were cut into pieces weighing around 50mg each, and placed into individual wells of 6-well plate containing pre-warmed 3mL media 199 (Gibco 11150-059) supplemented with 36μg/mL insulin (Lily Humilin R HI-213). Fat pieces were further cut into 8–10 smaller fractions, and incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 48h for acclimation. Following incubation, all fat pieces from each well were transferred into clean wells with 3mL pre-warmed fresh media prior to addition of several stimuli: LPS at a final concentration of 10μg/mL (Sigma L8643), heat-killed CS (HK-CS) at 2.4 × 104 cells/mL, PMA+Ionomycin at 81nM PMA and 1.3μM ionomycin (Invitrogen cell stimulation cocktail 00-4970), IL-1β at 5ng/mL (R&D Systems 401-ML-010), IL-17A at 20ng/mL (R&D Systems 7956-ML-025), TNFα at 10ng/mL (R&D Systems 410-MT-025), TGFβ-1 at 5ng/mL (R&D Systems 7666-MB-005), and angiotensin II at 100nM (Sigma-Aldrich A9525). HK-CS was prepared by incubating CS at 95°C for 1h. For the neutralization experiments with HK-CS, endogenous TNFα was inhibited by TNFα antibody at 1.3 μg/mL (Invitrogen PA5-46945) and TGFβ-1 by TGFβ-1 antibody at 1, 2, and 3 μg/mL (R&D Systems MAB1835). For TNFα neutralization, the antibody concentration was decided based on advanced verification of the antibody in data provided by the manufacturer. For TGFβ neutralization, the antibody concentration was chosen based on preliminary experiments in our lab, which validated the antibody for complete neutralization of rTGFβ at 2 ug/mL. Plates were incubated for 24 h at 37°C, 5% CO2, and media samples were collected at 6 and 24 h. Secreted PAI-1 protein in the media was measured by ELISA (Molecular Innovations MPAIKT-TOT) following manufacturer’s directions. At 24h, fat pieces were also collected for DNA purification and quantification. Fat pieces were digested overnight at 42°C with 100 μg/ml proteinase K and column-purified using the PureLinkTM genomic DNA kit (Invitrogen K1820-01) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Purified DNA was quantified using the Pico Green Assay (Invitrogen P11496) following manufacturer’s directions. Data were normalized to total DNA in each well and presented as PAI-1 in ng/μg DNA).

2.8. Adipocyte and stromal vascular fraction separation

Epididymal fat pads were collected from naïve and CS-injected mice and minced with scissors. Minced tissues were transferred to ice cold digestion buffer (0.5% BSA in HBSS with Ca2+Mg2+) and collagenase solution (1 mg/mL) was added. The mixture was incubated with shaking at 37°C for 50 minutes with vigorous shaking by hand every 10 minutes. Prior to the final 10 minutes, 10mM EDTA was added. Digested cells were passed through a 200um strainer and centrifuged at 500 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C to separate mature adipocytes and stromal vascular fraction (SVF) cells. The top adipocyte layer was collected, washed, and centrifuged three additional times to obtain a pure adipocyte fraction. The cell pellet (SVF) was treated with red blood cell lysis buffer for 5 minutes and the solution was passed through a 70um strainer and centrifuged at 500 × g for 10 minutes.

2.9. Analyses of immune cell populations by flow cytometry

Purified SVF cells from naïve mice were incubated in vitro with HK-CS (2.4 × 104 cells/mL) and GlogiPlug protein transport inhibitor (BD 555029) in 5%FBS-RPMI for 4 hr at 5%CO2, 37°C. Subsequently cells were stained with Fixable Viability Dye eFluor 450 (eBioscience 65-0843-14) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Blocking was performed using TruStain FcX (Biolegend 156603) for 10 minutes on ice and cells were further incubated for 30 minutes at 4°C in the dark with the following antibodies obtained from BioLegend: CD45 (103116), CD11b (101212), Ly6G (127616), CD3 (100204). Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Biolegend 420801) for 20 minutes at 4°C and stored overnight in the dark at 4°C. The following day, cells were permeabilized using Cytofix/Cytoperm Plus reagents (BD 555028) and intracellular staining for TNFα (Biolegend 506329) performed in combination with respective negative control (400433). Cells were analyzed on a FACSymphony A3 Cell Analyzer (BD, San Jose, CA). Analysis of flow cytometry data was performed using FlowJo data analysis software (FlowJo, LLC, Ashland, OR).

2.10. Magnetic purification of cell fractions

Selection of immune and non-immune cells from epidydimal fat SVF:

SVF from 8 aged mice was collected and pooled. Total SVF cell number varied from 3×106 to 1×107 among the three replicates. CD45 positive cells were purified by positive selection for CD45 with anti-mouse CD45 antibody (STEMCELL Technologies 60030AZ) and EasySep mouse APC positive selection kit with magnetic particles (STEMCELL Technologies, 17667) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The initial supernatant containing the CD45 negative fraction and the magnetically isolated CD45 positive fraction were washed 4 times by reapplying to the magnet to obtain pure fractions.

Selection of F4/80 and CD3 positive cells:

F4/80 positive cells from SVF (8 aged mice, 2 replicates) were purified by positive selection for F4/80 with anti-mouse F4/80 antibody (STEMCELL Technologies 60027PE.1) and EasySep mouse PE positive selection kit with magnetic particles (STEMCELL Technologies 17666), following the manufacturer’s directions. Magnetically isolated F4/80 positive cells were washed 4 times to obtain pure cells. The initial supernatant containing the remaining cells was then used to positively select for CD3 positive cells with anti-mouse CD3 antibody (STEMCELL Technologies 60015FI.1) and EasySep mouse FITC positive selection kit (STEMCELL Technologies 17668). Magnetically isolated CD3 positive cells were washed 3 times to obtain pure cells. The remaining immune cells were purified from the resultant supernatant after CD3 isolation by CD45 antibody and EasySep mouse APC positive selection kit. The remaining CD45 positive fraction was washed 3 times to obtain pure cells.

Selection of CD31 and CD34 positive cells:

CD31 positive cells from SVF (8–13 aged mice, 2 replicates) were purified by positive selection for CD31 with anti-mouse CD31 antibody (BioLegend 102405) and EasySep mouse FITC positive selection kit (STEMCELL Technologies 17668). Magnetically isolated CD31 positive cells were washed 4 times to obtain pure cells. The initial supernatant containing the remaining cells was then used to positively select for CD34 positive cells with anti-mouse CD34 antibody (BioLegend 119307) and EasySep mouse PE positive selection kit (STEMCELL Technologies 17666). Magnetically isolated CD34 positive cells were washed 3 times to obtain pure cells. The remaining immune cells were purified from the resultant supernatant after CD34 isolation by CD45 antibody and EasySep mouse APC positive selection kit (STEMCELL Technologies, 17667). The resultant supernatant containing non-immune cells was washed 3 times by reapplying to the magnet to obtain pure cells.

Protein Isolation from purified fractions:

Cell fractions were transferred into 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tubes, centrifuged at maximum speed at 4°C, and the pellets resuspended in 100 – 400 μL RIPA buffer with protease inhibitors, based on cell pellet size. Samples were vigorously vortexed for 3 pulses of 30s each. Protein lysates were separated from cell debris by another round of centrifugation. Protein content was determined using the DC protein assay (Bio-Rad 5000111).

2.11. Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were performed by or under the guidance of a qualified statistician (AJS). When normality and constant variance were reasonable assumptions, one-way ANOVA followed by pairwise comparisons using Dunnett’s test for comparison to control and Tukey’s Honest Significant Difference for all pairwise comparisons were used. When the control group had very low expression and very different distribution compared to experimental groups, the nonparametric Brown-Mood Median Test, followed by the Dunn method for comparisons to control was used. The Pearson correlation coefficient was used to study associations between two continuous variables. P-values more than 0.05 were considered not statistically significant.

3. RESULTS

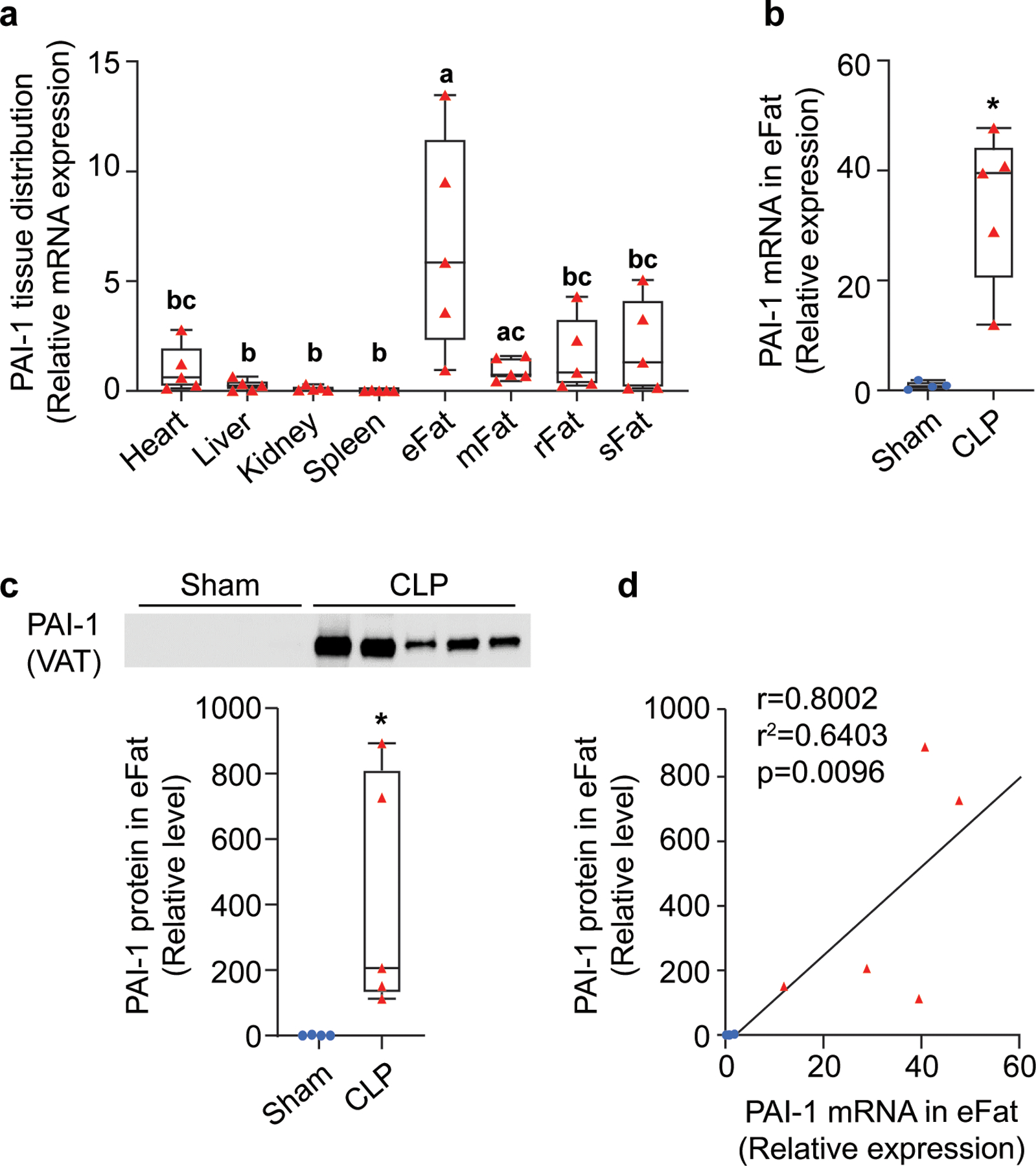

3.1. Adipose tissues are a major site for PAI-1 synthesis during sepsis

To determine which site, among the major organs and adipose tissue depots, contributes most to PAI-1 synthesis during polymicrobial abdominal sepsis, mRNA levels of PAI-1 were assessed in heart, liver, kidney, spleen, several visceral adipose tissue (VAT) depots (eFat: epididymal, mFat: mesenteric, rFat: retroperitoneal) and subcutaneous adipose tissue (sFat, intrascapular) of aged mice with CLP-induced sepsis (Figure 1a). Expression of PAI-1 in eFat, a VAT depot, was significantly higher than in all other organs and adipose tissue depots (p<0.05), with the exception of mFat. Transcript levels in eFat were on average 6.7-fold higher than in heart (p=0.0314), 25.9-fold higher than in liver (p=0.0378), 56.6-fold higher than in kidney (p=0.0387), 417.5-fold higher than in spleen (p=0.0389), 6.7-fold higher than in mFat (p=0.0603), 3.2-fold higher than in rFat (p=0.0372), and 4.3-fold higher than in sFat (p=0.0381). mFat PAI-1 expression levels were significantly higher than liver (p=0.299), kidney (p=0.0145), and spleen (p=0.0134), but comparable to heart and other fat depots. To further confirm sepsis-mediated induction of PAI-1 in this model, PAI-1 transcript (Figure 1b) and protein (Figure 1c) levels in eFat of sham and CLP mice were assessed; both mRNA and protein levels were significantly higher in CLP mice compared to sham (p=0.0237). Further, PAI-1 mRNA expression and protein levels in VAT showed a strong positive correlation (Figure 1d, r2=0.6403, p=0.0096). These findings demonstrate that PAI-1 is abundantly synthesized by adipose tissues of aged mice with polymicrobial sepsis, with VATs being the major site for synthesis.

Figure 1. Adipose tissues are a major site for PAI-1 synthesis during sepsis.

Polymicrobial sepsis was induced by CLP in aged mice (24 months old) which were euthanized 24h later for tissue collection. RNA and proteins were extracted from major organs and processed for qRT-PCR and Western blot analyses. (a) PAI-1 mRNA levels in various tissues of CLP mice, data are expressed relative to 18SrRNA transcript levels (tissues without a common letter (i.e. a, b, c) significantly differ, analyzed by paired t-tests, p<0.05); (b) PAI-1 mRNA levels in eFat of sham and CLP mice, data are expressed relative to 18SrRNA mRNA levels; (c) PAI-1 protein levels in in eFat of sham and CLP mice, intensity of each band was normalized to total protein content of each lane. *p<0.05 assessed by Brown-Mood median test (d) correlation between mRNA and protein levels in VAT assessed by Pearson correlation coefficient. Data are shown as individual values in box plots (n=5 each group) or correlation plots. eFat: epididymal fat; mFat: mesenteric fat; rFat: retroperitoneal fat; sFat: subcutaneous fat.

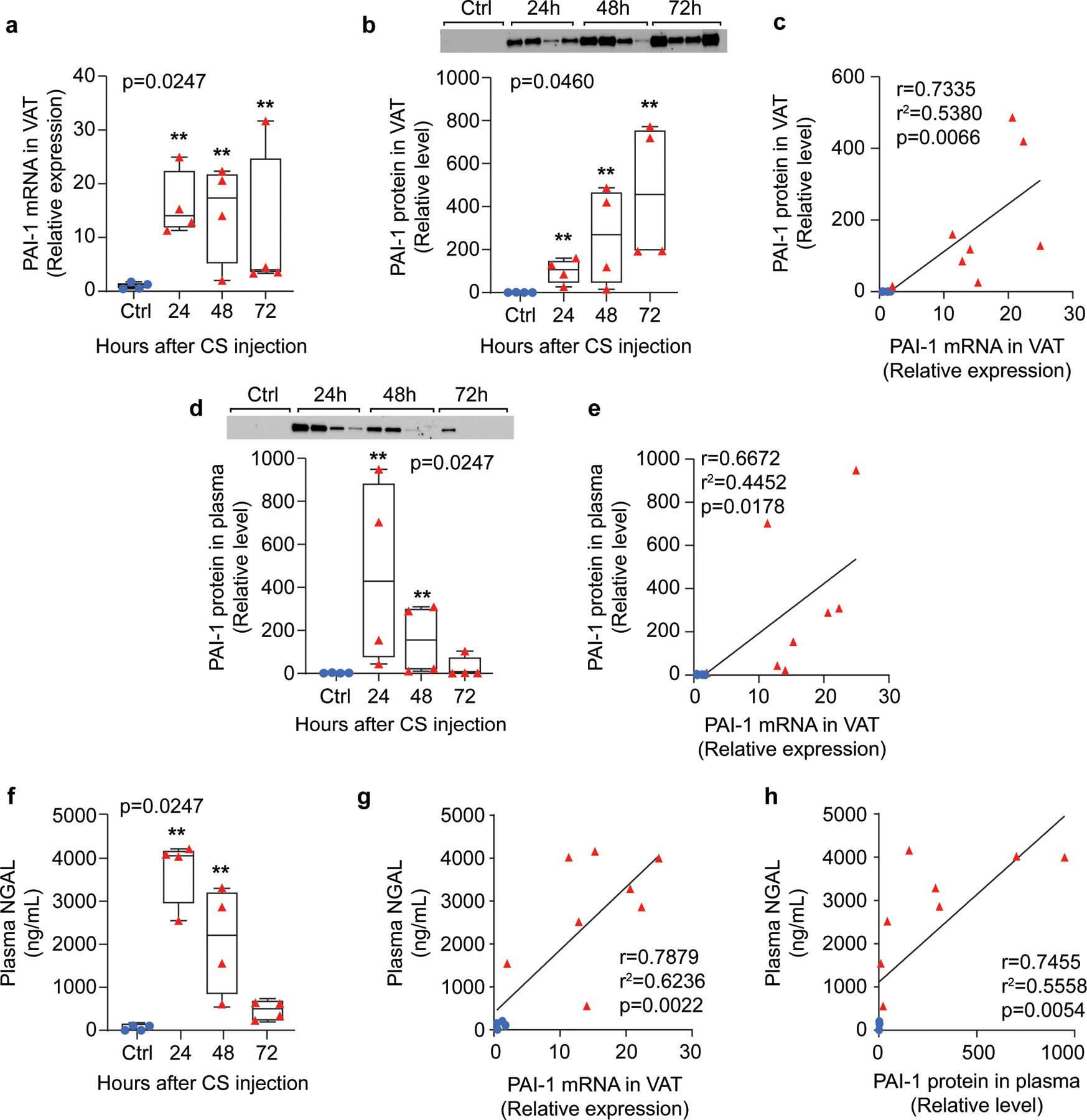

3.2. Sepsis-induced visceral adipose tissue synthesis of PAI-1 is reflected at the protein level in both visceral adipose tissue and plasma, and levels correlate with markers of acute kidney injury.

Due to multiple concerns regarding use of the CLP-model especially pertaining to age-related variabilities, such as dissimilarity in size and shape of cecum, changes in stool consistency, and differences in bacterial diversity of cecal contents (Starr et al., 2014), our laboratory recently moved to utilizing a cecal slurry (CS) model of polymicrobial sepsis whereby cecal contents from donor mice are uniformly injected into experimental mice. Using this model, we established the kinetics of PAI-1 induction in VAT at both the gene and protein level (Figure 2). PAI-1 transcript levels (Figure 2a) were strongly induced at 24h in all mice (16±6.1-fold) and levels remained significantly elevated compared to control mice through 48h (14.8±9.2-fold); with levels dropping in most mice by 72h though still remaining significantly elevated compared to control mice (10.8±13.9-fold). PAI-1 protein levels in VAT (Figure 2b) were similarly elevated at 24 and 48h (100-fold and 260-fold on average), but remained high through 72h, in contrast to mRNA levels. Interestingly, PAI-1 protein levels in VAT strongly matched the trajectory of PAI-1 mRNA levels through 48h (Figure 2c, r2=0.5380, p=0.006), but diverged at 72h. PAI-1 protein in the plasma was also measured and showed similar trends to VAT PAI-1 transcript levels with elevations at 24–48h, but resolving by 72h (Figure 2d). PAI-1 protein levels in plasma strongly matched the trajectory of PAI-1 mRNA levels in VAT through 48h (Figure 2e, r2=0.4452, p=0.018).

Figure 2. Sepsis-induced visceral adipose tissue synthesis of PAI-1 is reflected at the protein level in both visceral adipose tissue and plasma and levels correlate with markers of acute kidney injury.

Sepsis was induced in middle-aged mice (12 months old) by cecal slurry (CS) injection and mice were euthanized 24, 48, and 72h later for tissue and plasma collection. RNA and protein were extracted from visceral adipose tissues (epididymal depot) and processed for qRT-PCR or Western blot, respectively. (a) PAI-1 mRNA levels in VAT assessed by qRT-PCR, data are expressed relative to 18S mRNA levels; (b) Western blot and quantification for PAI-1 protein in VAT, intensity of each band was normalized to total protein content of each lane; (c) correlation of PAI-1 mRNA and PAI-1 protein levels in VAT for data points through 48h; (d) Western blot and quantification for PAI-1 protein in plasma, intensity of each band was normalized to total protein content of each lane; (e) correlation of PAI-1 mRNA in VAT and plasma PAI-1 VAT for data points through 48h; (f) plasma NGAL concentration measured by ELISA; (g) correlation of PAI-1 mRNA in VAT and plasma NGAL levels for data points through 48h; (h) correlation of PAI-1 protein in plasma and plasma NGAL levels for data points through 48h. All data are shown as individual values in box plots (n=4 each group) or correlation plots. Statistical differences were determined by Brown-Mood median test: overall p-values are depicted in upper left or right corner of plot, **p<0.01 indicate multiple comparison tests vs ctrl. Correlations were assessed by Pearson correlation coefficient. Ctrl: control; NGAL: neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin; VAT: visceral adipose tissue.

As our recent clinical study showed a strong positive association between PAI-1 (in both VAT and plasma) and development of acute kidney injury (AKI) (Zwischenberger et al., 2020), we sought to make the same association here in the preclinical model. Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL), a validated marker of acute kidney injury was used to assess kidney injury (Leelahavanichkul et al., 2016; Mori & Nakao, 2007; Schrezenmeier, Barasch, Budde, Westhoff, & Schmidt-Ott, 2017). Plasma NGAL levels were significantly higher at all timepoints in CS-injected mice compared to non-sepsis controls (p=0.0247, Figure 2f). For both PAI-1 mRNA levels in VAT and PAI-1 protein levels in plasma, a strong positive correlation was observed with plasma NGAL (r2=0.6236, p=0.0022 and r2=0.5558, p=0.0054, respectively, Figure 2g and 2h). These data establish the time course of PAI-1 induction locally in VAT and systemically in the circulation, as well as demonstrate that our recent clinical findings, regarding an association between VAT-derived PAI-1 and the development of AKI, can be replicated in a murine model of abdominal polymicrobial sepsis.

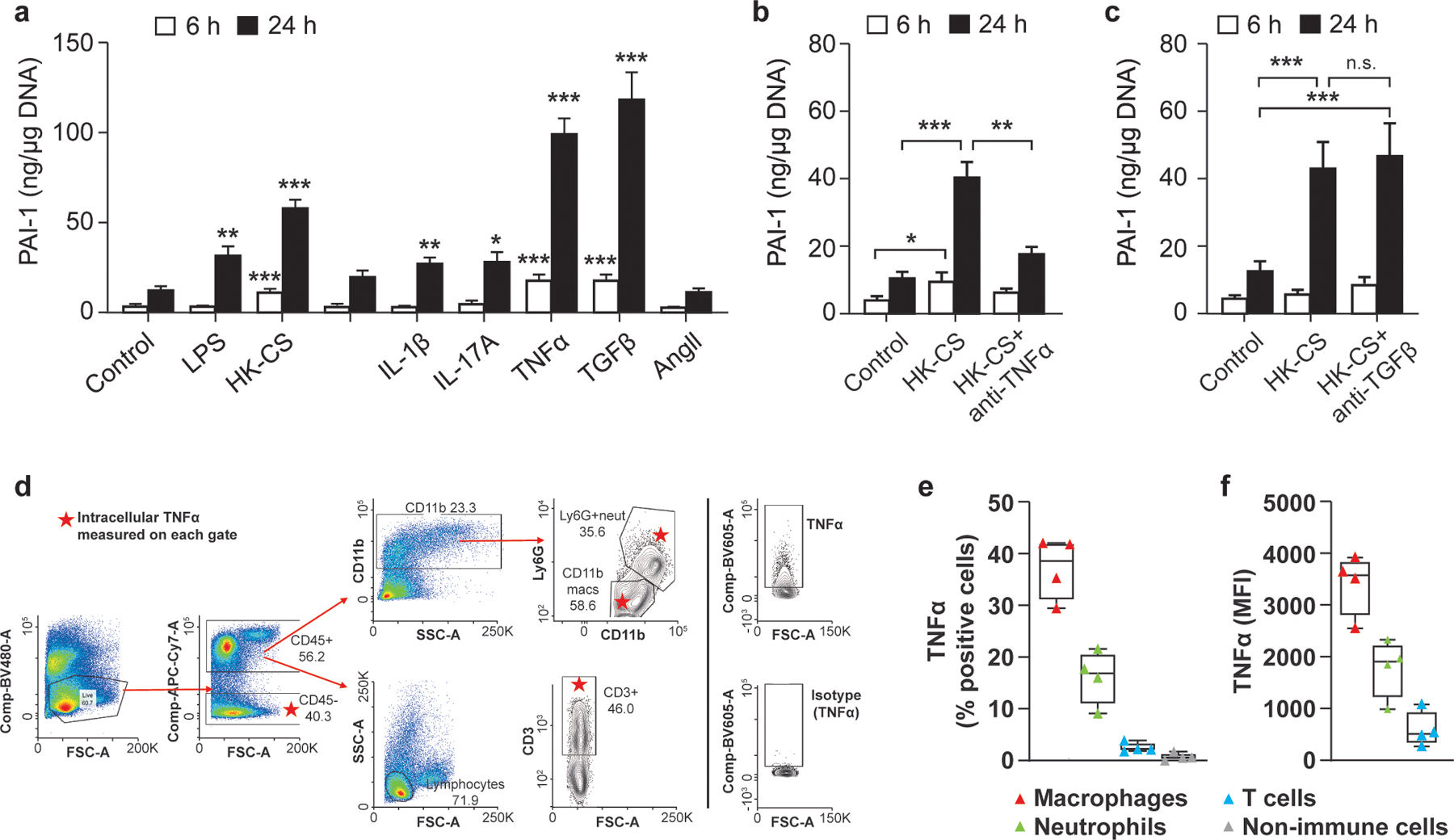

3.3. TNFα is a major endogenous inducer of PAI-1 in visceral adipose tissue.

To unravel the molecular signaling leading to PAI-1 induction locally in VAT, we used an ex vivo explant culture approach. Briefly, equal sized pieces of epididymal VAT were harvested from mice and stimulated ex vivo with various agents to mimic the effects of an acute infectious insult (LPS, heat-killed (HK)-CS, PMA/Ionomycin) as well as several known PAI-1 inducers (IL-1β (Olholm, Paulsen, Cullberg, Richelsen, & Pedersen, 2010), IL-17A (Wang et al., 2014), TNFα (Samad et al., 1996; Sawdey & Loskutoff, 1991), TGFβ-1 (Lundgren, Brown, Nordt, Sobel, & Fujii, 1996; Sawdey & Loskutoff, 1991), AngII (Skurk, Lee, & Hauner, 2001)). Among the infectious insult mimetics, LPS and HK-CS, but not PMA/Ionomycin significantly increased PAI-1 secretion above the control level (p=0.0045 and p<0.0001 at 24h, respectively) suggesting a primarily myeloid mechanism of activation (Figure 3a). Among the PAI-1 inducers, IL-1β, IL-17A, TNFα, and TGFβ1 significantly increased PAI-1 secretion above the control level (p=0.0020, 0.0375, <0.0001, and <0.0001, respectively); however, TNFα and TGFβ were clearly the most robust inducers (Figure 3a). To evaluate if endogenous TNFα or TGFβ contribute to PAI-1 secretion in sepsis conditions, explants were cultured with HK-CS and neutralizing antibodies for TNFα or TGFβ (Figure 3b and 3c). Neutralization of TNFα, but not TGFβ, significantly reduced PAI-1 secretion to the medium (p=0.0023), suggesting that endogenous TNFα is likely responsible for a majority of VAT PAI-1 production and secretion.

Figure 3. TNFα is a major endogenous inducer of PAI-1 in visceral adipose tissue.

Explant cultures of VAT from naïve aged mice (21–24 months old) were prepared in multiple separate experiments (tissues for each experiment were derived from 1–2 mice) and secretion of PAI-1 protein to the medium was assessed by ELISA. (a) Cultures were stimulated with LPS (10μg/mL), heat-killed cecal slurry (HK-CS, 2.4 × 104 cells/mL); PMA and Ionomycin (81nM PMA and 1.3μM ionomycin), and recombinant proteins IL-1β (5ng/mL), IL-17A (20ng/mL), TNFα (10ng/mL), TGFβ (5ng/mL), and angiotensin II (AngII, 100nM) and culture medium was sampled at 6 and 24h. Experiments were replicated at least twice for each condition with n=6–9 technical replicates for each treatment. (b) Cultures were stimulated with HK- CS, treated with a neutralizing antibody for TNFα (1.3 μg/mL), and culture medium sampled at 6 and 24h; experiment was repeated four times (3–4 technical replicates in each experiment) with similar trends. (c) Cultures were stimulated with heat-killed CS, treated with a neutralizing antibody for TGFβ (3 μg/mL), and culture medium sampled at 6 and 24h. Experiment was repeated twice (3 technical replicates for each experiment) with similar results. PAI-1 levels were normalized for adipose tissue DNA content of each well. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. Statistical differences were determined Brown-Mood median test or one-way ANOVA as described in Methods. (*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001). (d) Gating scheme for identification of the cellular source of TNFα in HK-CS stimulated adipose SVF cells. (e) Percent of cells positive for TNFα among different cell subsets. (f) Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) in TNFα expressing cells.

To determine the cellular source of TNFα, adipose SVF cells were obtained from naïve mice and incubated with HK-CS and a protein transport inhibitor, followed by extracellular labeling with markers for major immune cells subtypes (CD45+CD11b+Ly6Gneg: macrophages; CD45+CD11b+Ly6G+: neutrophils; CD45+CD3+: T cells, CD45neg: non-immune cells) and intracellular staining for TNFα. Using FACS analyses and the gating scheme depicted in Figure 3d, we determined that macrophages and neutrophils, but not T cells and non-immune SVF cells, provide a significant source of TNFα in HK-CS-stimulated adipose SVF cells (Figure 3e). Approximately 30–40% of macrophages and 10–20% of neutrophils were positive for TNFα (Figure 3e), with mean fluorescence intensity highest in the macrophages (Figure 3f).

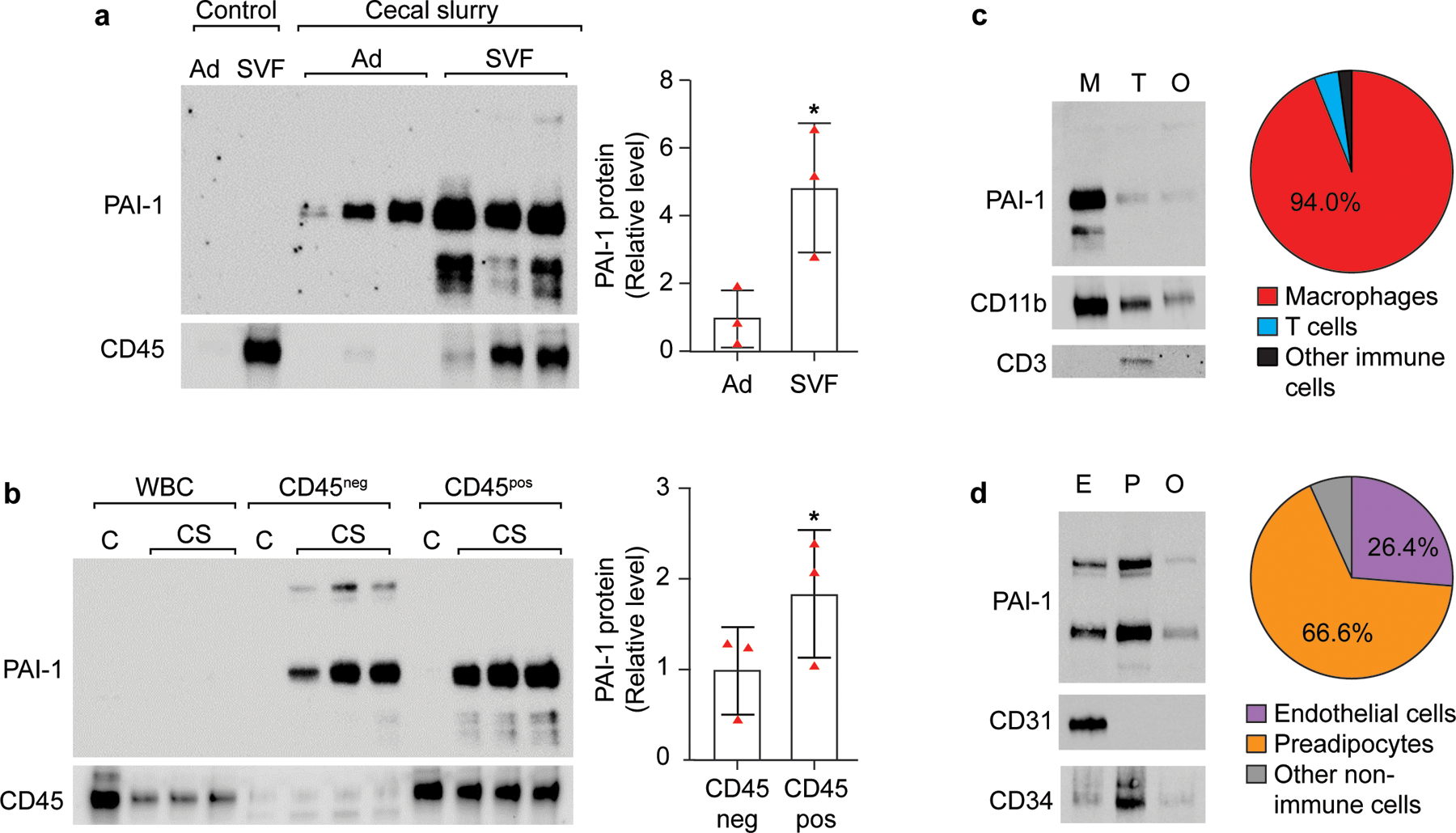

3.4. Sepsis-induced PAI-1 protein in visceral adipose tissue is localized primarily to adipose tissue macrophages (ATMs) and non-immune cells of the stromal vascular fraction (SVF).

To elucidate the cellular source of PAI-1 during sepsis, we first compared adipocyte and SVF expression of PAI-1 at the protein level by Western blot analyses (Figure 4a). In CS-injected mice, PAI-1 protein was localized to both the adipocyte and SVF cells with 4.9-fold higher levels in the SVF on average (p=0.0468). Bands for PAI-1 were not visible in the protein samples extracted from non-injected naïve mice. To determine whether PAI-1 localization within the SVF cells was primarily attributed to immune cells (CD45pos) or non-immune cells (CD45neg), we utilized immunomagnetic cell separation technology via positive selection (Figure 4b). This approach was chosen because we were unable to validate any commercially available anti-PAI-1 antibodies for intracellular FACS analyses. Due to the high number of cells required for this technology, VAT from several mice were pooled; thus, each band in the blot represents a pooled sample from 8 mice. Both CD45neg (primarily preadipocytes and endothelial cells) and CD45pos (multiple immune cell populations, but predominantly macrophages and T cells) showed abundant PAI-1 protein, with slightly higher levels in the CD45pos cells (1.86-fold, p=0.0162). Interestingly, in addition to the expected PAI-1 protein size (48kDa), CD45neg SVF cells uniquely expressed a heavily glycosylated form of PAI-1, roughly 100kDa in size. In contrast, a lower band corresponding to ~30kDa was detected primarily in CD45pos cells, in addition to the expected protein size (48kDa). PAI-1 protein was not detected in circulating white blood cells (WBC). Next, to determine which immune cell population is contributing most to PAI-1 levels, we performed immunomagnetic cell separation with positive selection for macrophages (F4/80+) and T cells (CD3+) (Figure 4c). PAI-1 protein was clearly localized to the macrophage fraction, encompassing 94% of all detected PAI-1. Similarly, to determine which among the non-immune cells (CD45 negative) produces the most PAI-1, CD31+ (endothelial cells) and CD34+ (preadipocytes) fractions were positively selected from adipose SVF cells by immunomagnetic purification (Figure 4d). While both endothelial cells and preadipocytes produced substantial PAI-1, a larger amount of protein appears to be derived from the preadipocyte fraction (66.6%). Collectively, these data demonstrate that adipose tissue macrophages (ATMs), and non-immune stromal cells (largely preadipocytes and endothelial cells) contribute to high PAI-1 protein levels in VAT of aged septic mice. Importantly, PAI-1 was not detected in circulating WBCs suggesting that high plasma PAI-1 levels during sepsis are derived from tissues.

Figure 4. Sepsis-induced PAI-1 protein in visceral adipose tissue is localized to both immune and non-immune cells of the stromal vascular fraction (SVF).

VAT from naïve control and CS-injected aged mice (21–24 months old) were digested with collagenase and adipocytes (Ad) and stromal vascular fraction (SVF) cells purified by repeated centrifugation. (a) Proteins were extracted from each fraction (n=1 non-injected control mouse, n=3 CS-injected mice) and PAI-1 quantified by Western blot analyses for CS-injected mice only, each band represents proteins from an individual mouse, intensity of each band was normalized to total protein content of each lane; (b) SVF cells obtained from pooled VAT were magnetically separated into CD45 positive and CD45 negative fractions; proteins were extracted from each fraction (n=1 non-injected control sample pooled from 8 mice, n=3 pools of VAT from CS-injected mice (n=6–8 mice for each pool)) and PAI-1 quantified by Western blot analyses for CS-injected mice only), intensity of each band was normalized to total protein content of each lane. Statistical differences were determined by one-sided paired t-tests as only increases were of interest, *p<0.05. (c) SVF cells were magnetically separated into macrophages (M, F4/80 positive), T cells (T, CD3 positive), and remaining CD45 positive cells (O, other immune cells depleted of CD3 and F4/80 positive cells); proteins were extracted from each fraction, and PAI-1 quantified by Western blot analyses. Data are representative of two experiments, each with pooled cells derived from 8 CS-injected mice. (d) SVF cells were depleted of CD45 positive cells, then by a series of positive selections, magnetically separated into endothelial cells (E, CD31), preadipocytes (P, CD34), and remaining CD45 negative cells; proteins were extracted from each fraction, and PAI-1 quantified by Western blot analyses. Data are representative of two experiments, each with pooled cells derived from 13 CS-injected mice.

4. DISCUSSION

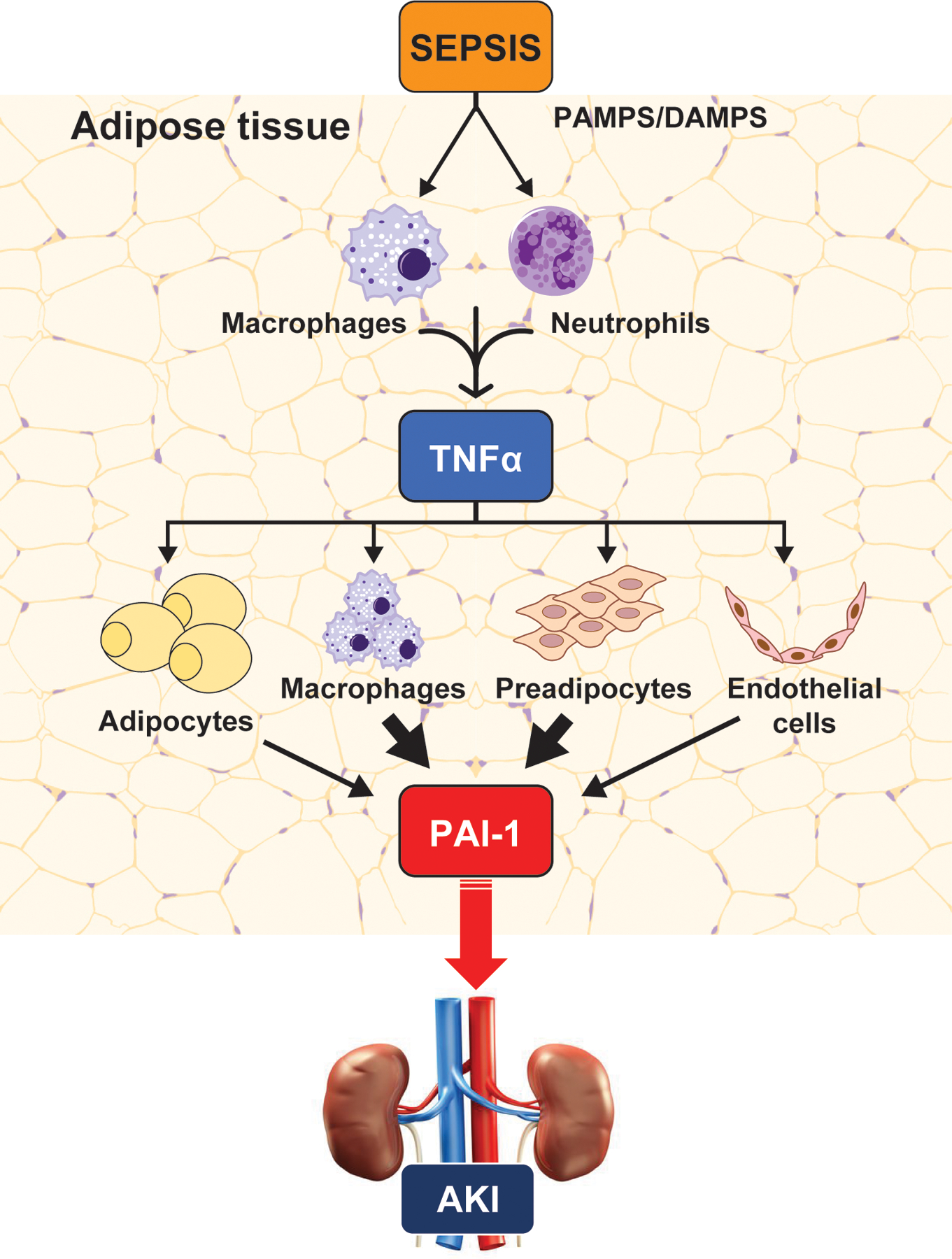

The involvement of adipose tissue, an active endocrine organ, has not been well-appreciated in acute critical illnesses such as sepsis. Here, using a clinically relevant murine model of polymicrobial abdominal sepsis, we show that adipose tissues (both visceral and subcutaneous) are a major source of the serine protease inhibitor PAI-1. We further demonstrate that PAI-1 transcript levels in visceral adipose tissue (VAT) match the trajectory of PAI-1 protein levels in both the VAT and circulation, suggesting that the VAT compartment contributes to systemic levels of PAI-1 in sepsis. We also confirm our recent clinical report establishing a connection between incidence of AKI and elevated PAI-1 in VAT (Zwischenberger et al., 2020), using our murine model which validates this preclinical model for studies related to VAT and abdominal sepsis. In an effort to unravel the cellular/molecular signaling leading to VAT-specific PAI-1 induction during sepsis, we found that TNFα appears to be the major endogenous inducer of PAI-1 in VAT stimulated with HK-CS, and that reducing signaling of this mediator decreases PAI-1 secretion from VAT by about 50%. Among the various cell types residing within VAT, we show that PAI-1 is in highest abundance in macrophages, preadipocytes, and endothelial cells and that paracrine communication between these cells and resident neutrophils and macrophages (major VAT producers of TNF), is likely critical for PAI-1 synthesis and secretion and the eventual downstream effects of circuiting PAI-1 on sepsis-associated AKI (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5. Mechanism and downstream effects of PAI-1 induction in VAT of septic mice.

Our collective data suggest that, during sepsis, TNFα in VAT is derived predominantly from macrophages and neutrophils; by paracrine signaling TNFα derived from these cells stimulates PAI-1 production and secretion from macrophages, preadipocytes, endothelial cells, and mature adipocytes. Adipose-derived PAI-1 is secreted into the circulation from the visceral adipose depots where it acts by inhibiting fibrinolysis. Consequently, due to the established effects of PAI-1 on promoting the continuation of thrombosis, intravascular coagulation and reduced blood flow result, contributing to organ injury, in particular acute kidney injury.

Since much attention has recently been given to the failure of murine models to appropriately recapitulate human pathophysiology and provide platforms for the development of successful interventions (Guillon et al., 2019), we elaborate briefly on specifics of our model which we believe heightens its clinical relevance. First, for all studies we used mice at middle- to old-age as these age groups more appropriately mimic the patient population which presents with sepsis (Starr & Saito, 2014). This is an important experimental variable given the propensity for aged individuals, as well as aged mice, to have natural age-related alterations in the physiology and functioning of major organ systems, underlying chronic comorbidities, and be a heterogeneous population in terms of overall health. Second, we utilized a model which induces severe sepsis (LD100) in the absence of antibiotic and fluid resuscitation; this protocol allows for the development of sepsis with organ injury, a critical component of clinical sepsis, yet includes resuscitation protocols to both mimic the clinical situation as well as allow for survival of the animals (~70–80% survival) for more prolonged studies (Owen et al., 2019; Steele et al., 2017). Indeed, using this model, we observed evidence of AKI (based on the biomarker NGAL). NGAL is among many biomarkers for both experimental and clinical AKI (Bagshaw et al., 2010; Haase et al., 2009; Schrezenmeier et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2020). It is proposed as an early biomarker as it appears in the serum and urine far earlier than standard markers, such as creatinine, allowing for early detection of AKI. It appears to be particularly useful in murine models due to evidence that creatine lacks sensitivity in the mouse (E. Singer et al., 2013). A limitation of our study is that we did not perform histopathological assessment of the kidney. Such studies have been performed with the major findings including tubular cell apoptosis, vacuolization of tubular cells, loss of brush border, and tubular cell swelling (Kosaka, Lankadeva, May, & Bellomo, 2016). Importantly, the current study remarkably mirrors the data presented in our recent clinical study on abdominal sepsis patients regarding PAI-1 in VAT and circulation, and incidence of AKI (Zwischenberger et al., 2020). As is typical in rodent modeling, we must admit certain limitations including that mice will never be human and as such all aspects of human pathophysiology cannot be replicated in our model, and while we provided supportive care in terms of antibiotics and fluid resuscitation, our model does not incorporate more advanced supportive care such as ventilator or vasopressor support. Nevertheless, we believe our model has multiple advantages over standard modeling practices in the sepsis field.

Adipose-derived PAI-1 has been recognized as an important mediator in multiple conditions including aging, obesity, insulin resistance, diabetes, metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, osteoporosis, sarcopenia, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, and cancer (Chen, Yan, Liu, Wang, & Wang, 2017; Kaji, 2016; Serrano et al., 2009). The connection between PAI-1 and these conditions is largely attributed to the major role of PAI-1 as an inhibitor of fibrinolysis, although other roles (angiogenesis, cellular migration, proliferation, wound healing, and senescence) of this pleiotropic mediator are now well-recognized and contribute to various pathophysiologies (Funcke & Scherer, 2019; Kaji, 2016). With respect to sepsis, most studies maintain that disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC)-mediated organ dysfunction is a downstream consequence of endothelial or platelet-derived PAI-1 and its direct effects on inhibition of plasminogen activators and plasmin activity (Iba & Thachil, 2017; Lijnen, 2005). PAI-1 likely plays other significant roles in sepsis which may manifest as investigations continue in the budding field of post-sepsis recovery. To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first to identify cellular sources of PAI-1 within VAT of septic mice. We found that in addition to enhanced expression by SVF cells compared to adipocytes, sepsis-induced PAI-1 is localized predominantly to macrophages, preadipocytes, and endothelial cells. These data bring new knowledge to the field regarding the complexity and tissue/cell-specific mechanisms by which PAI-1 is regulated. Our studies, along with those of others, give support to the notion that communication among the various immune and non-immune cell types residing within VAT promote systemic dissemination of PAI-1 and alter the pathophysiology of distant organs.

Interestingly, we found that gene and protein levels of PAI-1 in VAT are well correlated at 24 and 48h after sepsis induction; however, at 72h gene expression is resolving while protein levels remain elevated. On the other hand, plasma levels of PAI-1 matched the trajectory of mRNA induction over the entire time course (0–72h), with elevations at 24 and 48h but resolving by 72h. It has been previously noted that plasma PAI-1 concentrations are determined by the level of gene expression, because the half-life of PAI-1 is only 6 minutes and it is metabolized and cleared by the liver (Kaji, 2016). In our study, elevated PAI-1 protein in VAT at 72h, despite low levels of transcription at that time point suggests the possibility that secretion is being restricted yet the protein remains stable in the VAT. Further studies would be warranted to evaluate these suppositions.

Adipose tissue is a heterogeneous tissue containing mature adipocytes, preadipocytes, fibroblasts, stem cells, endothelial cells, nerve cells, and various immune cells including macrophages, neutrophils, T cells, and B cells. In this study we utilized explant cultures of VAT to investigate mechanisms of PAI-1 induction locally in VAT and its subsequent secretion. Explant culture is a useful technique to study molecular signaling because the integrity of the tissue is maintained along with the autocrine and paracrine interactions among the many cell types residing in VAT; therefore, signaling can be studied in a more physiologically relevant microenvironment (Yang, 2008). Using this platform, we found that PAI-1 was secreted from VAT in response to stimulation with LPS, but not PMA plus ionomycin suggesting that PAI-1 secretion is downstream of toll-like receptor 4 (LPS), but not protein kinase C (PMA+Iono) activation. In addition, we used heat-killed CS, which may more appropriately mimic the complexity of sepsis in vitro, including activation of pathways by both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. Using this broad stimulant, we found that inhibiting TNFα, but not TGFβ, significantly reduced PAI-1 secretion signifying TNFα as a major endogenous mediator. However, PAI-1 was not completely abolished, suggesting a potential contribution by other endogenous mediators such as IL-1β and IL-17A. Angiotensin II (Ang II) did not show significant effects regarding PAI-1 secretion. While rTGFβ induced PAI-1 secretion from VAT explants, inhibition of TGFβ after HK-CS treatment, did not reduce PAI-1 secretion, suggesting that endogenous TGFβ does not play a role in PAI-1 production. It is possible, however, that TGFβ protein arriving to the VAT from the circulation could influence PAI-1 production in vivo. This possibility was not investigated in this study. Finally, using FACS analyses, we observed that HK-CS-induced TNFα in VAT is localized predominantly to macrophages and neutrophils. Collectively, these data suggest that a majority of PAI-1 overproduction and secretion from VAT is the result of macrophage and neutrophil TNFα release and paracrine signaling to preadipocytes, endothelial cells, and macrophages.

Altogether our study reveals that in sepsis, PAI-1 originating from VAT likely contributes greatly to systemic levels and may influence DIC-mediated distant organ injury. Further, induction and secretion of PAI-1 is facilitated by a complex interaction among immune and non-immune cells of the VAT. Investigating these specific cell types and mediators could give rise to targeted therapies for reducing the impact of adipose-derived PAI-1 on distant organ injury in sepsis, as well as other similar acute and chronic inflammatory conditions.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by NIH grants R01GM129532 and R56AG061508 (awarded to MES) and R01 GM126181 and R01AG055359 (awarded to HS). The authors also gratefully acknowledge the Markey Cancer Center Research Communications Office for illustrative expertise.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

DATA AVAILABILITY

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article. Additional supporting information are available from the corresponding author upon request.

REFERENCES

- Alessi MC, Bastelica D, Morange P, Berthet B, Leduc I, Verdier M,…Juhan-Vague I (2000). Plasminogen activator inhibitor 1, transforming growth factor-beta1, and BMI are closely associated in human adipose tissue during morbid obesity. Diabetes, 49(8), 1374–1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angus DC, Linde-Zwirble WT, Lidicker J, Clermont G, Carcillo J, & Pinsky MR (2001). Epidemiology of severe sepsis in the United States: analysis of incidence, outcome, and associated costs of care. Crit Care Med, 29(7), 1303–1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagshaw SM, Bennett M, Haase M, Haase-Fielitz A, Egi M, Morimatsu H,…Bellomo R (2010). Plasma and urine neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin in septic versus non-septic acute kidney injury in critical illness. Intensive Care Med, 36(3), 452–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R, Yan J, Liu P, Wang Z, & Wang C (2017). Plasminogen activator inhibitor links obesity and thrombotic cerebrovascular diseases: The roles of PAI-1 and obesity on stroke. Metab Brain Dis, 32(3), 667–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chronopoulos A, Rosner MH, Cruz DN, & Ronco C (2010). Acute kidney injury in elderly intensive care patients: a review. Intensive Care Med, 36(9), 1454–1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Vincent JL, Adhikari NK, Machado FR, Angus DC, Calandra T,…Pelfrene E (2015). Sepsis: a roadmap for future research. Lancet Infect Dis, 15(5), 581–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddy AA (2002). Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 and the kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol, 283(2), F209–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekström M, Liska J, Eriksson P, Sverremark-Ekström E, & Tornvall P (2012). Stimulated in vivo synthesis of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 in human adipose tissue. Thromb Haemost, 108(3), 485–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elixhauser A, Friedman B, & Stranges E (2011). Septicemia in U.S. Hospitals, 2009: Statistical Brief #122. Agency fo Helathcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb122.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleischmann C, Scherag A, Adhikari NK, Hartog CS, Tsaganos T, Schlattmann P,…Trialists IF o. A. C. (2016). Assessment of Global Incidence and Mortality of Hospital-treated Sepsis. Current Estimates and Limitations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 193(3), 259–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flurkey K, Currer J, & Harrison D (2007). Mouse models in aging research. In: The mouse in Biomedical Research, 2 ed. Vol.3: Burlington: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Funcke JB, & Scherer PE (2019). Beyond adiponectin and leptin: adipose tissue-derived mediators of inter-organ communication. J Lipid Res, 60(10), 1648–1684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez H, Kellum JA, & Ronco C (2017). Metabolic reprogramming and tolerance during sepsis-induced AKI. Nat Rev Nephrol, 13(3), 143–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorina Y, Hoyert D, Lentzner H, & Goulding M (2005). Trends in causes of death among older persons in the United States. Aging Trends, (6), 1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillon A, Preau S, Aboab J, Azabou E, Jung B, Silva S,…Française), T. R. C. o. t. F. I. C. S. S. d. R. d. L. (2019). Preclinical septic shock research: why we need an animal ICU. Ann Intensive Care, 9(1), 66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta KK, Donahue DL, Sandoval-Cooper MJ, Castellino FJ, & Ploplis VA (2015). Abrogation of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1-vitronectin interaction ameliorates acute kidney injury in murine endotoxemia. PLoS One, 10(3), e0120728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta KK, Xu Z, Castellino FJ, & Ploplis VA (2016). Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 stimulates macrophage activation through Toll-like Receptor-4. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 477(3), 503–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haase M, Bellomo R, Devarajan P, Schlattmann P, Haase-Fielitz A, & Group N. M.-a. I. (2009). Accuracy of neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) in diagnosis and prognosis in acute kidney injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis, 54(6), 1012–1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoppensteadt D, Tsuruta K, Hirman J, Kaul I, Osawa Y, & Fareed J (2015). Dysregulation of inflammatory and hemostatic markers in sepsis and suspected disseminated intravascular coagulation. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost, 21(2), 120–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoste EA, Bagshaw SM, Bellomo R, Cely CM, Colman R, Cruz DN,…Kellum JA (2015). Epidemiology of acute kidney injury in critically ill patients: the multinational AKI-EPI study. Intensive Care Med, 41(8), 1411–1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iba T, & Thachil J (2017). Clinical significance of measuring plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 in sepsis. J Intensive Care, 5, 56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janand-Delenne B, Chagnaud C, Raccah D, Alessi MC, Juhan-Vague I, & Vague P (1998). Visceral fat as a main determinant of plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 level in women. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord, 22(4), 312–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaji H (2016). Adipose Tissue-Derived Plasminogen Activator Inhibitor-1 Function and Regulation. Compr Physiol, 6(4), 1873–1896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinasewitz GT, Yan SB, Basson B, Comp P, Russell JA, Cariou A,…Group, P. S. S. (2004). Universal changes in biomarkers of coagulation and inflammation occur in patients with severe sepsis, regardless of causative micro-organism. Crit Care, 8(2), R82–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosaka J, Lankadeva YR, May CN, & Bellomo R (2016). Histopathology of Septic Acute Kidney Injury: A Systematic Review of Experimental Data. Crit Care Med, 44(9), e897–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leelahavanichkul A, Somparn P, Issara-Amphorn J, Eiam-ong S, Avihingsanon Y, Hirankarn N, & Srisawat N (2016). Serum Neutrophil Gelatinase Associated Lipocalin (NGAL) Outperforms Serum Creatinine in Detecting Sepsis-Induced Acute Kidney Injury, Experiments on Bilateral Nephrectomy and Bilateral Ureter Obstruction Mouse Models. Shock, 45(5), 570–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levi M, & Poll T (2015). Coagulation in patients with severe sepsis. Semin Thromb Hemost, 41(1), 9–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levi M, & van der Poll T (2017). Coagulation and sepsis. Thromb Res, 149, 38–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lijnen HR (2005). Pleiotropic functions of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1. J Thromb Haemost, 3(1), 35–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorente L, Martín MM, Borreguero-León JM, Solé-Violán J, Ferreres J, Labarta L,…Páramo JA (2014). Sustained high plasma plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 levels are associated with severity and mortality in septic patients. Thromb Res, 134(1), 182–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundgren CH, Brown SL, Nordt TK, Sobel BE, & Fujii S (1996). Elaboration of type-1 plasminogen activator inhibitor from adipocytes. A potential pathogenetic link between obesity and cardiovascular disease. Circulation, 93(1), 106–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madoiwa S, Nunomiya S, Ono T, Shintani Y, Ohmori T, Mimuro J, & Sakata Y (2006). Plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 promotes a poor prognosis in sepsis-induced disseminated intravascular coagulation. Int J Hematol, 84(5), 398–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin GS, Mannino DM, & Moss M (2006). The effect of age on the development and outcome of adult sepsis. Crit Care Med, 34(1), 15–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mavri A, Stegnar M, Krebs M, Sentocnik JT, Geiger M, & Binder BR (1999). Impact of adipose tissue on plasma plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 in dieting obese women. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 19(6), 1582–1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyaji T, Hu X, Yuen PS, Muramatsu Y, Iyer S, Hewitt SM, & Star RA (2003). Ethyl pyruvate decreases sepsis-induced acute renal failure and multiple organ damage in aged mice. Kidney Int, 64(5), 1620–1631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montes R, Declerck PJ, Calvo A, Montes M, Hermida J, Muñoz MC, & Rocha E (2000). Prevention of renal fibrin deposition in endotoxin-induced DIC through inhibition of PAI-1. Thromb Haemost, 84(1), 65–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori K, & Nakao K (2007). Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin as the real-time indicator of active kidney damage. Kidney Int, 71(10), 967–970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newgard CB, & Sharpless NE (2013). Coming of age: molecular drivers of aging and therapeutic opportunities. J Clin Invest, 123(3), 946–950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neyra JA, Mescia F, Li X, Adams-Huet B, Yessayan L, Yee J,…Moe OW (2018). Impact of Acute Kidney Injury and CKD on Adverse Outcomes in Critically Ill Septic Patients. Kidney Int Rep, 3(6), 1344–1353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamura D, Starr ME, Lee EY, Stromberg AJ, Evers BM, & Saito H (2012). Age-dependent vulnerability to experimental acute pancreatitis is associated with increased systemic inflammation and thrombosis. Aging Cell, 11(5), 760–769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olholm J, Paulsen SK, Cullberg KB, Richelsen B, & Pedersen SB (2010). Anti-inflammatory effect of resveratrol on adipokine expression and secretion in human adipose tissue explants. Int J Obes, 34(10), 1546–1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen AM, Patel SP, Smith JD, Balasuriya BK, Mori SF, Hawk GS,…Saito H (2019). Chronic muscle weakness and mitochondrial dysfunction in the absence of sustained atrophy in a preclinical sepsis model. Elife, 8:e49920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pralong G, Calandra T, Glauser MP, Schellekens J, Verhoef J, Bachmann F, & Kruithof EK (1989). Plasminogen activator inhibitor 1: a new prognostic marker in septic shock. Thromb Haemost, 61(3), 459–462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raeven P, Feichtinger GA, Weixelbaumer KM, Atzenhofer S, Redl H, Van Griensven M,…Osuchowski MF (2012). Compartment-specific expression of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 correlates with severity/outcome of murine polymicrobial sepsis. Thromb Res, 129(5), e238–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rewa O, & Bagshaw SM (2014). Acute kidney injury-epidemiology, outcomes and economics. Nat Rev Nephrol, 10(4), 193–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rittirsch D, Hoesel LM, & Ward PA (2007). The disconnect between animal models of sepsis and human sepsis. J Leukoc Biol, 81(1), 137–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samad F, Yamamoto K, & Loskutoff DJ (1996). Distribution and regulation of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 in murine adipose tissue in vivo. Induction by tumor necrosis factor-alpha and lipopolysaccharide. J Clin Invest, 97(1), 37–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawdey MS, & Loskutoff DJ (1991). Regulation of murine type 1 plasminogen activator inhibitor gene expression in vivo. Tissue specificity and induction by lipopolysaccharide, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, and transforming growth factor-beta. J Clin Invest, 88(4), 1346–1353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrezenmeier EV, Barasch J, Budde K, Westhoff T, & Schmidt-Ott KM (2017). Biomarkers in acute kidney injury - pathophysiological basis and clinical performance. Acta Physiol, 219(3), 554–572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serrano R, Barrenetxe J, Orbe J, Rodríguez JA, Gallardo N, Martínez C,…Páramo JA (2009). Tissue-specific PAI-1 gene expression and glycosylation pattern in insulin-resistant old rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol, 297(5), R1563–1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimomura I, Funahashi T, Takahashi M, Maeda K, Kotani K, Nakamura T,…Matsuzawa Y (1996). Enhanced expression of PAI-1 in visceral fat: possible contributor to vascular disease in obesity. Nat Med, 2(7), 800–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer E, Marko L, Paragas N, Barasch J, Dragun D, Muller DN,…Schmidt-Ott KM (2013). Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin: pathophysiology and clinical applications. Acta Physiol, 207(4), 663–672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, Shankar-Hari M, Annane D, Bauer M,…Angus DC (2016). The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA, 315(8), 801–810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skurk T, Lee YM, & Hauner H (2001). Angiotensin II and its metabolites stimulate PAI-1 protein release from human adipocytes in primary culture. Hypertension, 37(5), 1336–1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starr ME, Hu Y, Stromberg AJ, Carmical JR, Wood TG, Evers BM, & Saito H (2013). Gene expression profile of mouse white adipose tissue during inflammatory stress: age-dependent upregulation of major procoagulant factors. Aging Cell, 12(2), 194–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starr ME, & Saito H (2014). Sepsis in old age: review of human and animal studies. Aging Dis, 5(2), 126–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starr ME, Steele AM, Cohen DA, & Saito H (2016). Short-Term Dietary Restriction Rescues Mice From Lethal Abdominal Sepsis and Endotoxemia and Reduces the Inflammatory/Coagulant Potential of Adipose Tissue. Crit Care Med, 44(7), e509–519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starr ME, Steele AM, Saito M, Hacker BJ, Evers BM, & Saito H (2014). A new cecal slurry preparation protocol with improved long-term reproducibility for animal models of sepsis. PLoS One, 9(12), e115705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starr ME, Takahashi H, Okamura D, Zwischenberger BA, Mrazek AA, Ueda J,…Saito H (2015). Increased coagulation and suppressed generation of activated protein C in aged mice during intra-abdominal sepsis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol, 308(2), H83–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starr ME, Ueda J, Takahashi H, Weiler H, Esmon CT, Evers BM, & Saito H (2010). Age-dependent vulnerability to endotoxemia is associated with reduction of anticoagulant factors activated protein C and thrombomodulin. Blood, 115(23), 4886–4893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele AM, Starr ME, & Saito H (2017). Late Therapeutic Intervention with Antibiotics and Fluid Resuscitation Allows for a Prolonged Disease Course with High Survival in a Severe Murine Model of Sepsis. Shock, 47(6), 726–734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swarbreck SB, Secor D, Ellis CG, Sharpe MD, Wilson JX, & Tyml K (2015). Effect of ascorbate on plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 expression and release from platelets and endothelial cells in an in-vitro model of sepsis. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis, 26(4), 436–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tipoe TL, Wu WKK, Chung L, Gong M, Dong M, Liu T,…Wong SH (2018). Plasminogen Activator Inhibitor 1 for Predicting Sepsis Severity and Mortality Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Immunol, 9, 1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vignon P, Laterre PF, Daix T, & François B (2020). New Agents in Development for Sepsis: Any Reason for Hope? Drugs, 80(17):1751–1761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G, Wu K, Li W, Zhao E, Shi L, Wang J,…Tao K (2014). Role of IL-17 and TGF-β in peritoneal adhesion formation after surgical trauma. Wound Repair Regen, 22(5), 631–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Murphy SL, Kochanek KD, & Bastian BA (2016). Deaths: Final Data for 2013. Natl Vital Stat Rep, 64(2), 1–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto K, Shimokawa T, Yi H, Isobe K, Kojima T, Loskutoff DJ, & Saito H (2002). Aging accelerates endotoxin-induced thrombosis : increased responses of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 and lipopolysaccharide signaling with aging. Am J Pathol, 161(5), 1805–1814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto K, Takeshita K, Kojima T, Takamatsu J, & Saito H (2005). Aging and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) regulation: implication in the pathogenesis of thrombotic disorders in the elderly. Cardiovasc Res, 66(2), 276–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang K (2008). Adipose tissue protocols (2nd ed.). Totowa, N.J.: Humana Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang CF, Wang HJ, Tong ZH, Zhang C, Wang YS, Yang HQ,…Shi HZ (2020). The diagnostic and prognostic values of serum and urinary kidney injury molecule-1 and neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin in sepsis induced acute renal injury patients. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci, 24(10), 5604–5617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwischenberger BA, Balasuriya BK, Harris DD, Nataraj N, Owen AM, Bruno MEC,…Starr ME (2021). Adipose-Derived Inflammatory and Coagulant Mediators in Patients with Sepsis. Shock, 55(5):596–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article. Additional supporting information are available from the corresponding author upon request.