Abstract

This study was performed to investigate the frequency of human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) infection of the liver in children with a variety of liver diseases and to evaluate the role of HHV-6 infection in pediatric patients with prolonged non-B non-C hepatitis. Detection of the HHV-6 genomes in liver, in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC), and in plasma was performed by PCR or by in situ hybridization. Liver biopsy materials from 48 patients, in whom HHV-6 infection was serologically confirmed, were available for PCR analysis. Sequences of the HHV-6B genome were detectable in the livers of 36 of 48 patients (75%). The presence of the genome was not associated with serum transaminase activities. The genome was detectable in PBMC of 22 of 31 (71%) patients tested. In these 31 patients HHV-6 was detected in both the livers and PBMC of 20, was detected in PBMC but not in the livers of 2, was detected in the livers but not in PBMC of 3, and was detected in neither of samples of 6. In situ hybridization of the livers of six patients showed the presence of the HHV-6B genome in the nuclei of hepatocytes. The anti-HHV-6 immunoglobulin M antibody was detectable in 2 of 9 of the non-B non-C hepatitis patients, whereas none of the 22 patients with etiology-defined liver diseases tested positive. Cell-free viral DNA was not detectable in either group of patients. Our results showed that HHV-6B is frequently present in the livers of children with a variety of liver diseases but do not support the assumption that HHV-6B infection of the liver is associated with prolonged non-B non-C hepatitis.

In 1986, human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) was first isolated from the lymphocytes of a patient with lymphoproliferative disorder (11). HHV-6 is now divided into two distinct classes designated HHV-6A and HHV-6B or variant A and variant B (5). Yamanishi et al. (21) reported that HHV-6 is a causative agent of exanthem subitum, and HHV-6 has since been shown to be associated with a spectrum of diseases, including febrile convulsions (9), encephalopathy (7), and liver disease. HHV-6 infection has also been associated with acute liver injury and fulminant hepatitis (2, 5, 15, 18). Recently we have used an in situ hybridization method to show that hepatocytes primarily infected with HHV-6 in the liver of a patient with chronic hepatitis were associated with persistent HHV-6 infection (19). Our case report suggested that HHV-6 may cause prolonged liver dysfunction through direct hepatocytopathy.

Infection with HHV-6, which is usually acquired in early childhood (10), is widespread in the human population, as shown by the presence of specific antibodies in >90% of healthy adults (12). As a result of the primary infection, HHV-6 is presumed to establish a latent infection, and the viral DNA can be detected in the salivary glands, lymph nodes, urinary tracts, skin, and genital tracts (4). Previous studies have reported that the viral genome was not detectable in the livers of patients who underwent liver transplantation (22). However, the frequency of HHV-6 infection in the liver has not been studied in healthy individuals or in patients with other liver diseases, including non-B non-C hepatitis. Therefore, we considered it important to determine the incidence of HHV-6 infection in the livers of these patients.

In this study, we used PCR methods to determine the presence of HHV-6-specific genomes in the livers of pediatric patients with various liver diseases. We then evaluated the role of HHV-6 infection in children with prolonged liver dysfunction of unknown etiology.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients.

During 10 years, from 1991 to 2000, approximately 260 pediatric patients underwent a liver biopsy in our institute as part of their diagnosis of liver disease or assessment of chronic liver disease. Their liver diseases included hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection (n = 75), hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection (n = 65), non-B non-C hepatitis (n = 28), neonatal hepatitis (n = 17), biliary atresia (n = 12), primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC; n = 12), fatty liver (n = 10), cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection (n = 8), autoimmune hepatitis (n = 8), glycogen storage disease (GSD; n = 7), Alagille syndrome (n = 6), Wilson disease (n = 6), and other diseases (n = 6). For some patients written informed consent to preserve extra liver tissue for future studies was obtained. Liver biopsy materials were immediately frozen in dry ice–2-methylbutane and kept in a deep freezer at −80°C until the time of study. At least one sample of liver biopsy tissue from each of 48 patients was available for a molecular determination of HHV-6 (Tables 1 and 2). Liver diseases of these 48 subjects included HBV infection (n = 11), HCV infection (n = 7), non-B non-C hepatitis (n = 9), neonatal hepatitis (n = 3), PSC (n = 2), fatty liver (n = 2), CMV infection (n = 2), GSD (n = 2), and Alagille syndrome (n = 4). In addition we had available single patients with Dubin-Johnson syndrome, biliary atresia, biliary cirrhosis, congenital fibrosis, congestive heart disease, and Wilson disease. Thirty-one of the 48 subjects were also tested for the presence of the HHV-6 genome in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) at the time of their liver biopsies.

TABLE 1.

Results of serum ALT and PCR study for the HHV-6 genomes and tests for anti-HHV-6 antibodies in patients with detectable HHV-6 genomes in the liver

| Case | Liver diseasea | Sexd | Age (yr-mo) | Serum ALT (U/liter) | PCR result for:

|

Antibody titer

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liverb | PBMCc | Plasma | IgG | IgM | |||||

| 1 | Biliary atresia | f | 0-10 | 226 | + | + | 320 | ||

| 2 | NBNC | f | 0-10 | 238 | + | + | − | 640 | |

| 3 | DJS | m | 0-7 | 24 | + | − | 320 | ||

| 4 | NBNC | m | 1-1 | 131 | + | + | − | 1,280 | 20 |

| 5 | HCV | m | 1-1 | 62 | + | + | − | 1,280 | |

| 6 | CMV | m | 1-2 | 186 | + | + | − | 320 | |

| 7 | NBNC | m | 1-4 | 52 | + | + | − | 80 | |

| 8 | NBNC | m | 1-6 | 208 | + | + | − | 2,560 | |

| 9 | NBNC | m | 1-8 | 235 | + | + | − | 1,280 | 10 |

| 10 | Neonatal hepatitis | f | 1-8 | 11 | + | − | 160 | ||

| 11 | GSD | m | 2-0 | 67 | + | 160 | |||

| 12 | GSD | m | 2-1 | 170 | + | + | 640 | ||

| 13 | Neonatal hepatitis | m | 2-4 | 48 | + | + | − | 160 | |

| 14 | Congenital fibrosis | f | 2-5 | 6 | + | 80 | |||

| 15 | NBNC | m | 2-8 | 19 | + | + | − | 640 | |

| 16 | NBNC | m | 2-9 | 14 | + | − | − | 160 | |

| 17 | HCV | m | 3-1 | 48 | + | − | 320 | ||

| 18 | CMV | m | 3-4 | 181 | + | + | 640 | ||

| 19 | HBV | m | 4-7 | 40 | + | + | − | 320 | |

| 20 | CHD | m | 6-4 | 12 | + | 320 | |||

| 21 | HBV | f | 6-8 | 129 | + | + | − | 160 | |

| 22 | HBV | m | 7-3 | 68 | + | − | 80 | ||

| 23 | HCV | m | 7-8 | 22 | + | + | 640 | ||

| 24 | HBV | m | 10-7 | 506 | + | + | 160 | ||

| 25 | PSC | m | 10-8 | 14 | + | + | 640 | ||

| 26 | HCV | f | 11-0 | 22 | + | − | 80 | ||

| 27 | Alagille syndrome | f | 11-7 | 116 | + | − | 160 | ||

| 28 | HBV | m | 11-8 | 16 | + | − | 80 | ||

| 29 | Biliary cirrhosis | m | 12-10 | 60 | + | + | 320 | ||

| 30 | HBV | m | 12-2 | 41 | + | − | 80 | ||

| 31 | HBV | m | 13-0 | 63 | + | − | 80 | ||

| 32 | PSC | m | 14-7 | 120 | + | + | 640 | ||

| 33 | HBV | m | 19-6 | 96 | + | − | 640 | ||

| 34 | HBV | m | 20-0 | 51 | + | − | 40 | ||

| 35 | HCV | m | 20-11 | 9 | + | − | 40 | ||

NBNC, non-B non-C hepatitis; DJS, Dubin-Johnson syndrome; CHD, congestive heart disease.

Positivity rate, 35 of 35.

Positivity rate, 20 of 23.

f, female; m, male.

TABLE 2.

Results of serum ALT and PCR study for the HHV-6 genomes and tests for anti-HHV-6 antibodies in patients without HHV-6 genomes in the livera

| Case | Liver disease | Sexd | Age (yr-mo) | Serum ALT (U/liter) | PCR result for:

|

Antibody titer

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liverb | PBMCc | Plasma | IgG | IgM | |||||

| 36 | Alagille syndrome | m | 0-10 | 114 | − | 640 | |||

| 37 | NBNC | m | 1-3 | 34 | − | + | − | 80 | |

| 38 | Neonatal hepatitis | m | 1-4 | 48 | − | − | 80 | ||

| 39 | Fatty liver | m | 3-3 | 23 | − | − | 160 | ||

| 40 | NBNC | f | 5-4 | 50 | − | − | − | 1,280 | |

| 41 | Alagille syndrome | f | 6-4 | 151 | − | + | − | 1,280 | |

| 42 | Wilson's disease | m | 6-5 | 385 | − | − | 80 | ||

| 43 | HBV | m | 9-3 | 61 | − | − | − | 320 | |

| 44 | Fatty liver | m | 10-6 | 241 | − | 160 | |||

| 45 | HCV | m | 11-7 | 212 | − | − | 80 | ||

| 46 | HCV | m | 12-3 | 52 | − | − | 320 | ||

| 47 | HBV | m | 12-5 | 14 | − | − | 40 | ||

| 48 | Alagille syndrome | m | 15-11 | 301 | − | 160 | |||

NBNC, non-B non-C hepatitis.

Positivity rate, 0 of 13.

Positivity rate, 2 of 8.

m, male; f, female.

Of the 48 patients, 37 underwent a liver biopsy when their liver disease was in the active stage. Patients were classified as having active disease by an elevation in their alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels (mean of 136.9 U/liter with a range of 34 to 506 U/liter). In the remaining 11 patients a liver biopsy was performed when they showed normal ALT activities (15.8 [range, 6 to 24] U/liter). A liver biopsy was needed to assess the histology after the resolution of the liver diseases in eight patients and to make a diagnosis of noninflammatory liver disease in three patients. The underlying disease of these 11 patients included HBV infection (n = 2), HCV infection (n = 2), and non-B non-C hepatitis (n = 2), with single patients diagnosed with neonatal hepatitis, PSC, hepatic fibrosis, fatty liver, or congestive heart disease. Of the eight patients that had resolved their liver disease, six patients showed a natural remission while two patients sustained remission after interferon therapy for chronic HBV infection. The histology revealed minimal, or no, inflammation of the liver in these eight patients.

For this study we defined prolonged non-B non-C hepatitis by the following standards: an elevation in serum ALT (≧30 U/liter) for more than 3 months and negative serologic markers for hepatitis A virus, HBV, HCV, CMV, and Epstein-Barr virus with undetectable hepatitis G virus genome in the serum. Of the 48 patients enrolled 9 met these criteria (Tables 1 and 2) and were subjected to further evaluation. Their mean age at onset was 5.6 months (range, 1 to 15 months), and their mean age at the time of liver biopsy was 24 months (range, 10 to 64 months). A patient whose case was previously reported (19) was also included.

Markers for other viruses.

Serum samples were tested for hepatitis B surface (HBs) antigen, anti-HBs, and anti-hepatitis A immunoglobulin M (IgM) by radioimmunoassay and were analyzed for anti-HCV with a second-generation enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. HCV RNA in the serum was assayed by the reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) method (17). Hepatitis G virus RNA in the serum was also assayed by an RT-PCR method described by Simons et al. (14). Specific antibodies were assayed for Epstein-Barr virus and CMV.

Specific tests for HHV-6 infection. (i) Antibody detection.

Titers of IgG and IgM antibodies against HHV-6 in sera were determined by an indirect immunofluorescence assay (1).

(ii) Sample preparation, PCR, and detection of PCR products.

PBMC were mixed with K buffer (20) (105 PBMC in 10 μl of K buffer) and incubated for 3 h at 56°C as previously described (8). Samples were then heated at 98°C for 10 min to denature proteinase K and immediately cooled on ice. Nucleic acids were extracted from 100 μl of plasma using the sodium iodine method (Wako Pure Chem. Ind. Ltd., Osaka, Japan). Twenty microliters of the extract was used as a template for PCR. DNA in the liver was extracted using the QIAamp tissue kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). PCR for the detection of HHV-6 DNA in PBMC, plasma, and liver tissue was performed as previously described (8). A nested PCR was adopted by using the primers derived from the immediate-early gene locus of HHV-6. The sequences of the outer primers were 5′-TTCTCCAGATGTGCCAGGGAAATCC-3′ and 5′-CATCATTGTTATCGC TTTCACTCTC-3′. The sequences of the inner primers were 5′-AGTGACAGATCTGGGCGGCCCTAATAACTT-3′ and 5′-AGGTGCTGAGTGATCAGTTTCATAACCAAA-3′.

The PCR was performed in 0.5-ml microcentrifuge tubes in a thermal cycler (Perkin-Elmer Cetus). The incubation mixture, with a total volume of 40 μl, contained 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 50 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 200 μM (each) deoxynucleoside triphosphate, and 2.5 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Takara Shuzo, Kyoto, Japan). Ten microliters of sample was subjected to 30 cycles of amplification. The cycle consisted of a 1-min denaturation step at 94°C, a 2-min annealing step at 62°C, and extension steps of 3, 4, and 5 min at 72°C for 10 cycles. The outer primers were used at 1.0 μM each. After the first run of 30 cycles, 5 μl of the PCR product was added to 45 μl of reaction mixture containing 1.0 μM inner primers (the reaction mixture was the same as in the first PCR). All samples were prepared and assayed twice. In the PCR assay, we used distilled water as the negative control in each assay.

Five microliters of the reaction mixture was subjected to electrophoresis on a 2.0% agarose gel, and DNA was located by UV fluorescence after staining with ethidium bromide. HHV-6 can be classified into HHV-6A and -6B using the PCR primers described above (20). The first PCR amplification products were 325 bp for HHV-6A and 553 bp for HHV-6B. The nested double-PCR amplification products were 195 bp for HHV-6A and 421 bp for HHV-6B.

(iii) Southern blot hybridization of amplified product.

To confirm the specificity of the PCR amplification products, a hybridization technique with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated oligonucleotide probes was performed. The sequence of the specific oligodeoxynucleotide probe for HHV-6B was 5′-TAAATCCATTACTGGCCTTGAA-3′ (3). Five microliters of PCR product was separated by electrophoresis, and DNA was transferred to a nylon membrane. The membrane was treated with 0.4 N NaOH for 4 h and then neutralized with 4× standard saline citrate (SSC; 0.6 M NaCl, 0.06 M sodium citrate) for 15 min. After the membrane was dried at 37°C for a few hours, prehybridization (5× SSC with 0.5% polyvinylpyrrolidone, 0.5% bovine serum albumin fraction V, and 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS]) was performed for 15 min at 50°C. Hybridization was performed for 15 min at 50°C by shaking with the equivalent of 100 ng of HHV-6B-specific probe/ml in sealed plastic bags containing 5× SSC, 0.5% polyvinylpyrrolidone, 0.5% bovine serum albumin fraction V, 1% SDS, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM ZnCl2, and 0.1% sodium azide. The membrane was washed once with 2× SSC with 1% SDS for 10 min at 50°C and then washed once with 1× SSC with 0.5% Triton X-100 for 10 min at room temperature. The membrane was then placed in the color-producing reagents, which contained 0.33 mg of 4-nitroblue tetrazolium chloride/ml and 0.17 mg of 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate (BCIP)/ml, for 30 min at 37°C in the dark.

(iv) In situ hybridization of liver tissue.

The digoxigenin-labeled HHV-6 probe used for in situ hybridization was prepared by using a PCR labeling method. The labeled PCR product was amplified from the immediate-early gene locus of HHV-6B (19). In situ hybridization was carried out on formaldehyde-fixed, paraffin-embedded liver sections. Paraffin was removed by incubation in xylene and serial ethanol washes of decreasing concentrations. The sections were digested with 1 mg of proteinase K/ml for 10 min at 37°C. Denaturation was performed in 70% formamide–2× SSC for 3 min at 75°C. Hybridization buffer contained 0.02 M Tris-HCl, 0.3 M NaCl, 2% salmon sperm DNA, 1× Denhardt solution, 10% sodium dextran sulfate, and 50% formamide. After prehybridization for 1 h at 42°C, the sections were hybridized with the denatured HHV-6B probe diluted in the same buffer (1:50) overnight at 42°C followed by two washings in 1× SSC for 5 min at 50°C. The hybridization probe was immunohistochemically detected by using alkaline phosphatase-conjugated antidigoxigenin antiserum and visualized with BCIP and 4-nitroblue tetrazolium chloride.

RESULTS

HHV-6 infection in the 48 subjects enrolled for this study was confirmed by the presence of anti-HHV-6 antibodies in their serum at the time of liver biopsy. The HHV-6B genome was detected in the livers of 36 of the 48 patients (75%) using the nested-PCR method (Tables 1 and 2). The viral genome was also detectable in PBMC of 22 of the 31 (71%) patients tested. The genomes detected in both the liver and PBMC were all those of HHV-6B as demonstrated by the lengths of the PCR products and by Southern blot hybridization using the variant-specific probe. In 20 patients the HHV-6 genome was detected in both the liver and PBMC. In three patients the genome was detectable in the liver but not in PBMC, and in two patients it was detectable in PBMC but not in the liver. In the remaining six patients the virus was undetectable in either PBMC or the liver.

When analyzed in terms of activities of liver disease at liver biopsy, HHV-6B DNA was detectable in 9 of the 11 patients (82%) with normal ALT activities and in 27 of 37 patients (73%) who showed elevated levels of transaminases (P = 0.436). In a particular patient with prolonged CMV hepatitis (case 18), whose liver function normalized after treatment with high-titer anti-CMV gamma globulin and ganciclovir, HHV-6B was detectable in the liver by PCR both prior to the therapy and 15 months after the resolution of CMV hepatitis.

The 48 subjects were divided into two groups, DNA positive (Table 1) and DNA negative (Table 2), according to the presence of HHV-6B DNA in the liver, and the demographic data for these two groups of patients were compared. Distributions by sex and age for the two groups were not statistically different. When analyzed in terms of diagnosis, the viral DNA was detectable in 24 of 29 patients with viral hepatitis, in 8 of 12 with cholestatic disease, and in 4 of 7 patients with other liver disease. The rates of occurrence among these three disease groups were not statistically significantly different. Furthermore, the rates of occurrence of cholestatic liver disease and noncholestatic liver disease were similar (8 of 12 versus 28 of 36; P = 0.874). The rate of detection of the HHV-6B genomes in PBMC correlated positively with the detection of HHV-6 in the liver (20 of 23 versus 2 of 8; P = 0.002). However, the presence of HHV-6B DNA in the liver was not associated with levels of anti-HHV-6 IgG antibodies in serum, whether compared on the basis of the mean titer of antibodies or on the basis of the distribution of high-titer patients (data not shown).

To investigate the role of HHV-6 infection in prolonged non-B non-C hepatitis, nine patients were studied for the presence of the IgM antibody to HHV-6 and for cell-free viral DNA as a marker of active viral replication (Tables 1 and 2). In addition, 22 patients with liver diseases of known etiology from the 48 subjects were also assessed (22 for the IgM antibody and 15 for free virus). The anti-HHV-6 IgM antibody was detectable in two of nine of the non-B non-C hepatitis group, whereas no patients with etiology-defined liver diseases tested positive. Cell-free viral DNA was not detectable in any patient of either group.

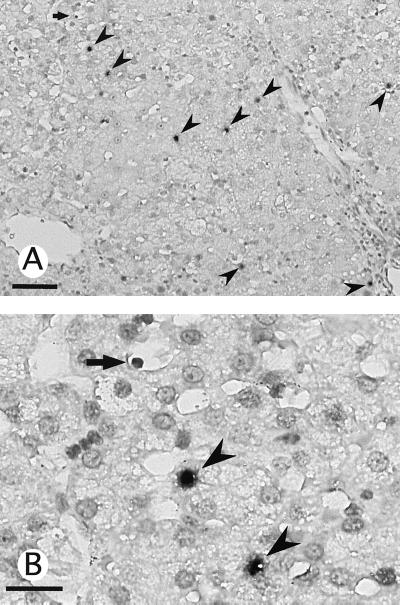

In situ hybridization for HHV-6B DNA in liver tissue was performed in six cases, including three cases of non-B non-C hepatitis, one case of chronic hepatitis B, one case of chronic hepatitis C, and one case of CMV hepatitis (Table 1). Hybridization signals were primarily found within the nuclei of the parenchymal hepatocytes and, to a lesser extent, within a few sinusoidal mononuclear cells (Fig. 1). No HHV-6-positive cells were found within either the portal tracts or the biliary epithelial cells, with the exception of case 12, for which hybridization signals were observed within the nuclei of the biliary epithelial cells (19).

FIG. 1.

Detection of HHV-6 DNA in the liver by in situ hybridization prior to anti-CMV therapy in case 18. Positive signals were found mostly within the nuclei of the hepatocytes (arrowheads), with a few signals located within the smaller nuclei of sinusoidal mononuclear cells (arrows). Original magnifications: ×33 (bar, 100 μm) (A) and ×132 (bar, 50 μm) (B).

DISCUSSION

In the present study the sequences of the HHV-6B genome but not of the HHV-6A genome were detectable in the livers of 75% of the children with a variety of liver diseases. Our findings suggest that HHV-6B does not reside only in lymphocytes within the liver but can also infect hepatocytes. In our study the genome of HHV-6 was detectable in the livers of three children but undetectable in their PBMC. Additional experiments, using in situ hybridization to probe liver tissue, found HHV-6B DNA more prominently located in hepatocytes than in intrahepatic mononuclear cells. In vitro studies have shown that HHV-6 can infect human hepatoma cell line Hep G2 cells (6). This is consistent with our results showing that HHV-6B can infect hepatocytes with a high frequency. Further studies are needed to elucidate whether HHV-6B can establish latent infection within the liver as it does in the salivary glands and in lymph nodes.

We analyzed the association of viral infection and liver disease at the time of liver biopsy. HHV-6B DNA was detectable in 82% of the patients with normal ALT activities, including the patient whose CMV-associated hepatitis had resolved. A similar detection rate (73%) in those who showed elevated levels of transaminases was observed. These findings suggest that HHV-6B infection of the liver may not be the cause of liver injury in patients whose underlying liver diseases are inactive.

We observed a high correlation between the detection of HHV-6B genomes in the liver and in PBMC. This finding suggests that HHV-6B infection is more widespread and viral load is greater in children who had viral infection in their liver than in those without hepatic involvement. Otherwise, neither sex, age, the diagnosis of liver disease, nor the titer of anti-HHV-6 antibodies was associated with the presence of HHV-6B DNA in the liver.

Yoshikawa et al. (22) reported that HHV-6 DNA was not detected in the livers of living related liver transplant recipients. The discrepancy between our findings and that report may be explained by the difference in the techniques used to assay for the virus. The Yoshikawa study used sections of liver tissue cut from paraffin-embodied blocks. In our study liver tissue to be assayed was immediately frozen and stored frozen until the PCR assay. Another possibility is that cholestasis suppresses infection of hepatocytes with HHV-6. A majority of their patients had biliary atresia and associated cholestatic liver disease. However, this is less likely since six of nine of our cholestatic patients also tested positive for HHV-6 DNA, a rate similar to that for noncholestatic patients.

Our study evaluates the occurrence of HHV-6 infection in children with prolonged liver dysfunction of unknown etiology. Since HHV-6 DNA is ubiquitous and since infection can be latent, the mere detection of viral DNA in tissues gives no information about the association between HHV-6 and disease (4). To detect the presence of active HHV-6 infection, we tested for IgM and/or free viral DNA in the plasma. In our study two of nine children with non-B non-C hepatitis tested positive for the IgM antibody whereas none of the patients with liver disease of known etiology were positive. However, the presence of anti-viral IgM antibodies might not necessarily indicate active infection. A periodic reactivation of latent HHV-6 is suggested by the observation that 4 to 5% of healthy donors may be positive for the presence of the HHV-6-specific IgM antibody (16). Therefore, the use of assays that detect the presence of the viral DNA in serum or plasma may add important information about the role of HHV-6 in specific disease (4).

Viral DNA has been reported to be detectable in the serum of 86% of children with exanthem subitum and in 22% of human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients but is not found in healthy adults (13). This suggests that HHV-6 replication might be tightly controlled in individuals with competent immune systems. In our study cell-free viral DNA was not detectable in patients with non-B non-C hepatitis or in those with hepatitis of known etiology. Our results do not support an assumption that persistent infection of the liver with HHV-6 may have an association with prolonged non-B non-C hepatitis. It is possible that in some patients with non-B non-C hepatitis, where known agents have been definitely excluded, persistent infection with HHV-6 could be a cause of their liver disease. In such patients an active immune response might confine viral infection within the liver to the extent that detectable virus is not shed into the circulation. Further studies are required to elucidate any association between HHV-6 infection and prolonged non-B non-C hepatitis by comparing HHV-6 hepatitis patients with control subjects of similar ages whose liver function is normal.

In conclusion, our results showed that HHV-6B is frequently present in the livers of children with various liver diseases. Our study does not provide evidence to support the hypothesis that persistent HHV-6B infection of the liver may have an association with prolonged non-B non-C hepatitis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We acknowledge the valuable advice of Stephen Brooks and Carolyn Young.

REFERENCES

- 1.Asada H, Yalcin S, Bakachandra K, Higashi K, Yamanishi K. Establishment of titration system for human herpesvirus 6 and evaluation of neutralizing antibody response to the virus. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:2204–2207. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.10.2204-2207.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asano Y, Yoshikawa T, Suga S, Yazaki T, Kondo K, Yamanishi K. Fatal fulminant hepatitis in an infant with human herpesvirus 6 infection. Lancet. 1990;335:862–863. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)90983-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aubin J T, Collandre H, Candotti D, Ingrand D, Rouzioux C, Burgard M, Richard S, Huraux J M, Agut H. Several groups among human herpesvirus 6 strains can be distinguished by Southern blotting and polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:367–372. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.2.367-372.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Di Luca D, Mirandola P, Ravaioli T, Bigoni B, Cassai E. Distribution of HHV-6 variants in human tissues. Infect Agents Dis. 1996;5:203–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dubedat S, Kappagoda N. Hepatitis due to human herpesvirus-6. Lancet. 1989;ii:1463–1464. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)92077-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Inagi R, Guntapong R, Nakao M, Ishino Y, Kawanishi K, Isegawa Y, Yamanishi K. Human herpesvirus 6 induces IL-8 gene expression in human hepatoma cell line, Hep G2. J Med Virol. 1996;49:34–40. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9071(199605)49:1<34::AID-JMV6>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ishiguro N, Yamada S, Takahashi T, Takahashi Y, Togashi T, Okuno T, Yamanishi K. Meningo-encephalitis associated with HHV-6 related exanthem subitum. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1990;79:987–989. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1990.tb11369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kondo K, Hayakawa Y, Mori H, Sato S, Kondo T, Takahashi K, Minamishima Y, Takahashi M, Yamanishi K. Detection by polymerase chain reaction amplification of human herpesvirus 6 DNA in peripheral blood of patients with exanthem subitum. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:970–974. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.5.970-974.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kondo K, Nagafuji H, Hata A, Tomomori C, Yamanishi K. Association of human herpesvirus 6 infection of the central nervous system with recurrence of febrile convulsions. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:1197–1200. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.5.1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Okuno T, Takahashi K, Balachandra K, Shiraki K, Yamanishi K, Takahashi M, Baba K. Seroepidemiology of human herpesvirus 6 infection in normal children and adults. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:651–653. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.4.651-653.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salahuddin S Z, Ablashi D V, Markham P D, Josephs S F, Sturzenegger, Kaplan M, Halligan G, Biberfeld P, Wong-Staal F, Kramarsky B, Gallo R C. Isolation of a new virus, HBLV, in patients with lymphoproliferative disorders. Science. 1986;234:596–601. doi: 10.1126/science.2876520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saxinger C, Polesky H, Eby N, Grufferman S, Murphy R, Tegtmeir G, Parekh V, Memon S, Hung C. Antibody reactivity with HBLV (HHV-6) in U.S. populations. J Virol Methods. 1998;21:199–208. doi: 10.1016/0166-0934(88)90066-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Secchiero P, Carrigan D R, Asano Y, Benedetti L, Crowley R W, Komaroff A L, Gallo R C, Lusso P. Detection of human herpesvirus 6 in plasma of children with primary infection and immunosuppressed patients by polymerase chain reaction. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:273–280. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.2.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Simons J N, Leary T P, Dawson G J, Pilot-Matias T J, Muerhoff A S, Schlauder G G, Desai S M, Mushahwar I K. Isolation of novel virus-like sequences associated with human hepatitis. Nat Med. 1995;1:564–569. doi: 10.1038/nm0695-564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sobue R, Miyazaki H, Okamoto M, Hirano M, Yoshikawa, Suga S, Asano Y. Fulminant hepatitis in primary human herpesvirus-6 infection. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1290. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199105023241818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suga S, Yoshikawa T, Asano Y, Nakashima T, Yazaki T, Fukuda, Kojima S, Matsuyama T, Ono Y, Oshima S. IgM neutralizing antibody responses to human herpesvirus-6 in patients with exanthem subitum or organ transplantation. Microbiol Immunol. 1992;36:495–506. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1992.tb02047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tada K, Tajiri H, Kozaiwa K, Sawada A, Guo W, Okada S. Role of screening for hepatitis C. virus in children who presented with malignant diseases and underwent bone marrow transplantation. Transfusion. 1997;37:641–644. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1997.37697335160.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tajiri H, Nose O, Baba K, Okada S. Human herpesvirus-6 infection with liver injury in neonatal hepatitis. Lancet. 1990;335:863. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)90984-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tajiri H, Tanaka-Taya K, Ozaki Y, Okada S, Mushiake S, Yamanishi K. Chronic hepatitis in an infant associated with human herpesvirus 6 infection. J Pediatr. 1997;131:473–475. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(97)80082-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yamamoto T, Mukai T, Kondo K, Yamanishi K. Variation of DNA sequence in immediate-early gene of human herpesvirus 6 and variant identification by PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:473–476. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.2.473-476.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamanishi K, Okuno T, Shiraki K, Takahashi M, Asano Y, Kurata T. Identification of human herpesvirus 6 as causal agent for exanthem subitum. Lancet. 1988;ii:1065–1067. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)91893-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yoshikawa T, Suzuki K, Ihira M, Furukawa H, Suga S, Iwasaki T, Kurata T, Asonuma K, Tanaka K, Asano Y. Human herpesvirus 6 latently infects mononuclear cells but not liver tissue. J Clin Pathol. 1999;52:65–67. doi: 10.1136/jcp.52.1.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]